Volume 16, Issue 1 (March 2018)

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2018, 16(1): 35-44 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rezaee H, Younesi J, Farahbod M, Ranjbar M. Determining the Effectiveness of a Modulated Parenting Skills Program on Reducing Autistic Symptoms in Children and Improvement of Parental Adjustment. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2018; 16 (1) :35-44

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-530-en.html

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-530-en.html

1- Razi Psychiatric Hospital,University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Measuring and Assessment, Faculty of Psychology and Education, Allameh Tabataba'i University, Tehran, Iran.

3- Health Care Management, Research Institute of Exceptional Children, Ministry of Education, Tehran, Iran.

4- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Measuring and Assessment, Faculty of Psychology and Education, Allameh Tabataba'i University, Tehran, Iran.

3- Health Care Management, Research Institute of Exceptional Children, Ministry of Education, Tehran, Iran.

4- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 689 kb]

(1607 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (5861 Views)

Full-Text: (1331 Views)

1. Introduction

Generally, when a child is diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, many tensions may have stepped into the realm of the family [1, 2]. The family with a child who is clearly different from other children experiences a wave of fear and confusion and seeks psychiatric or counseling care to find the reason behind their child’s difference. Literature suggests that the greatest amount of stress and grief is experienced when a family hears the word ‘autism’ for the first time [3-5]. Lack of information [6], coping and management of child behavior problems, troublesome and time consuming treatments strategies, financial challenges, and having access to certain treatment centers [7] are some of the major stressors in the family. Terrifying stresses compromise the mental and physical health of family members, especially parents [8] and bring them to the borders of depression [9]. The rate of divorce in such families shows the chaotic environment due to low parental adjustment and autistic symptoms and disorders. Naseef and Freedman reported 80 percent divorce rate in families with autistic children in the USA [7], while Hartley et al. showed 23.5% divorce rate in a smaller group of such families [10]. This is a significantly higher rate of divorce compared to the families with normal children (13.8%). The same situation holds in Iranian families. Khooshabi reported that mothers who take care of their autistic child have significantly lower mental health compared to others [11]. There is a high essentiality for supportive role and close relationship of the couples and their adjustment in improving the conditions of children and families in all communities [12].

Although there are many evidences regarding the problems of an autistic child’s parents, most documents have reported children as the target population in treatment programs [6]. Whereas, previous studies suggest that special plans for parents tended to improve their mental health, marital adjustment, and effective coping with providing the scientific and reasonable care of the child [6, 13, 14]. Parents and families of autistic children are their only major teachers. Therefore, they should certainly be educated and supported [15-17]. Educational programs can reduce negative feelings and effects. Meanwhile, increasing self-efficacy in parents, which leads to their marital adjustment and satisfaction [18], higher capability in enforcement of Communication skills in an autistic child, and better management of difficult behavior challenges [14, 19]. Hence, nowadays ‘Autism’ therapy considers training parents as well [20, 21].

Most Iranian research literature regarding autism has focused on autistic children as the target [22]. There are a few studies, which specifically point out the significance of training the parents, or address their problems in Iran [23-25]. Therefore, this study aims to develop and evaluate the effectiveness of a modulated program of parenting skills in reducing autistic symptoms, and to increase parents’ adjustment.

2. Methods

Participants

Among the families referred to the rehabilitation centers in Tehran city, 26 couples who have a 3-6 year old autistic child diagnosed by a psychiatrist, and were living together during 2012-2013 volunteered to participate in this study.

Instruments

Gilliam Autism Rating Scale (GARS)

Gilliam Autism Rating Scale (GARS) is a behavioral check list to evaluate the severe behavioral disorder in 3-22 year old individuals. It has 56 items in four subscales: Stereotyped Behaviors, Social Interaction, Communication and Developmental Disturbance, which rates each behavior in four levels. The internal consistency of the subscales is reported as 0.90, 0.93, 0.89, 0.88, respectively, and the total score was considered reliable using Chronbach’s Alpha (0.96). The construct reliability of the questionnaire was correlated with the Autism Behavior Checklist (ABC), 0.94 in totals, and 0.37-0.92 for their subscales [26].

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS)

Lovibond and Lovibond developed the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS) with 42 items to evaluate the symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress in adults [27]. The reliability of the depression, anxiety, and stress subscales was reported 0.91, 0.84, and 0.90, respectively. This is a diagnostic and concurrently valid questionnaire. Each subscale can be scored between 0-42.

Procedure

The present study had two phases; descriptive design at first to develop the plan followed by a semi-experimental pre-posttest research design with a control group for evaluation. In the initial phase, a large-scale field study was conducted over the existing therapeutic methods for children with autism. Then, 12 parents of autistic children were interviewed about their educational needs and problems in their own opinion. The techniques with approved efficacy in the research literature were incorporated based on the positive parenting structure and considering the counseling approach. Most of the techniques were selected from cognitive-behavioral therapy since the study population was the parents. Because they can understand their children and then take an active part in the treatment process through increasing their acceptance and capabilities. Both of the parents were encouraged to participate in the treatment process in this study, while previous studies suggested that usually one of the parents –especially the father- would be excluded. The researchers believed that this dual participation could enhance their marital adjustment and close relationship besides increasing their responsibility toward the treatment.

The final plan was developed from the initial incorporated plan after being evaluated, modified, and confirmed by four professionals in the field of autistic children through Delphi method. Table 1 shows the abstract of the parenting sessions in this study.

In this program, the sessions 4, 6, 8, and 13 were held separately for each couple with cognitive behavior approach, and sessions 14 and 15 were held for each family concentrating on the whole family with CBT approach. The family members were free to take part in these two sessions. Each absent parent would receive a brochure of the session to keep him or her in the process. All the sessions were conducted by a professional counselor or psychologist.

The second phase began right after developing the plan. As mentioned, the researchers designed a pre-posttest controlled trial for the clients who were referred to the rehabilitation centers in Tehran and who agreed and registered to participate. Twenty-six parents were selected among those registered, and were randomly assigned in two groups, control and experiment. All participants completed the questionnaires twice, once before starting the sessions, and once right after the end of the final session. The control group received no intervention regarding parent education at the time and had only the routine rehabilitative treatments.

Data analysis

Gilliam Autism Rating Scale has total score and four subscales. Differences of the subscale means between two groups were analyzed using Multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA). Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to analyze each subscale in pre-posttest, if the difference of total score was significant. Mean of GARS total score in posttest had been regarded as dependent variable and the covariate would be mean of total score in pretest, which would be examined by analysis of variance. Differences between mean of total score in DASS were analyzed by analysis of covariance considering mean of total score in pretest as the dependent variable, whereas mean of total score in posttest would be the covariate.

3. Results

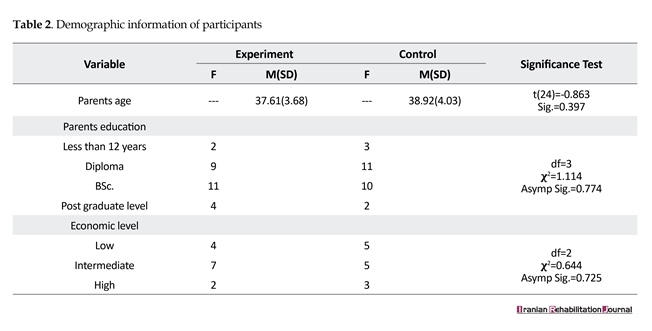

Table 2 shows demographic information of the research sample. Independent t student results showed no significant difference between the two groups (P>0.05, t(24)=0.863). There was no significant difference in education (P>0.05, X2=1.114, df=3) and economic level (P>0.05, X2=0.644, df=2) between the two groups.

The variance-covariance matrices consistency (P<0.05), homogeneity of variances (P<0.05), and homogeneity of regression coefficients (P<0.05) were studied to test the first hypothesis and three basic assumptions of multivariate analysis of covariance. Results showed that these assumptions were set at 95 percent. The results of multivariate analysis of covariance showed that all four multivariate measures -Wilks’ Lambda, Pillai’s trace, Hotelling trace, and Roy’s largest root- are significant at the 99% confidence level (F(4,17)=5.690, P=0.004).

Thus, the null hypothesis is rejected and the linear combination of the four dependent variables shows that posttest components means -stereotyped behavior, communication, social interaction and development- were affected significantly by independent variable (Positive Parent Training Program), whereas the differences of four pretest means of the covariates have been eliminated. On the other hand, results suggested that the independent variable made reliable and significant changes on the means of four dependent variables in a linear combination. We used Analysis of Covariance to evaluate the effect of the independent variable on each dependent variable separately (Table 3).

According to Table 3, the experiment and control group did not significantly differ in terms of Stereotyped Behaviors (F(1,20)=4.30, P=0.053) and Development (F(1,20)=0.448, P=0.511) at 99% confidence level after eliminating the pretest effect. This indicated that the positive parent-training program did not statistically differ in its efficacy in reducing stereotyped behaviors and improving development of autistic children. On the contrary, the result of ANCOVA which eliminates the pretest effect, determines that this program could significantly change the means of communication (F(1,20)=10.07,

Generally, when a child is diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, many tensions may have stepped into the realm of the family [1, 2]. The family with a child who is clearly different from other children experiences a wave of fear and confusion and seeks psychiatric or counseling care to find the reason behind their child’s difference. Literature suggests that the greatest amount of stress and grief is experienced when a family hears the word ‘autism’ for the first time [3-5]. Lack of information [6], coping and management of child behavior problems, troublesome and time consuming treatments strategies, financial challenges, and having access to certain treatment centers [7] are some of the major stressors in the family. Terrifying stresses compromise the mental and physical health of family members, especially parents [8] and bring them to the borders of depression [9]. The rate of divorce in such families shows the chaotic environment due to low parental adjustment and autistic symptoms and disorders. Naseef and Freedman reported 80 percent divorce rate in families with autistic children in the USA [7], while Hartley et al. showed 23.5% divorce rate in a smaller group of such families [10]. This is a significantly higher rate of divorce compared to the families with normal children (13.8%). The same situation holds in Iranian families. Khooshabi reported that mothers who take care of their autistic child have significantly lower mental health compared to others [11]. There is a high essentiality for supportive role and close relationship of the couples and their adjustment in improving the conditions of children and families in all communities [12].

Although there are many evidences regarding the problems of an autistic child’s parents, most documents have reported children as the target population in treatment programs [6]. Whereas, previous studies suggest that special plans for parents tended to improve their mental health, marital adjustment, and effective coping with providing the scientific and reasonable care of the child [6, 13, 14]. Parents and families of autistic children are their only major teachers. Therefore, they should certainly be educated and supported [15-17]. Educational programs can reduce negative feelings and effects. Meanwhile, increasing self-efficacy in parents, which leads to their marital adjustment and satisfaction [18], higher capability in enforcement of Communication skills in an autistic child, and better management of difficult behavior challenges [14, 19]. Hence, nowadays ‘Autism’ therapy considers training parents as well [20, 21].

Most Iranian research literature regarding autism has focused on autistic children as the target [22]. There are a few studies, which specifically point out the significance of training the parents, or address their problems in Iran [23-25]. Therefore, this study aims to develop and evaluate the effectiveness of a modulated program of parenting skills in reducing autistic symptoms, and to increase parents’ adjustment.

2. Methods

Participants

Among the families referred to the rehabilitation centers in Tehran city, 26 couples who have a 3-6 year old autistic child diagnosed by a psychiatrist, and were living together during 2012-2013 volunteered to participate in this study.

Instruments

Gilliam Autism Rating Scale (GARS)

Gilliam Autism Rating Scale (GARS) is a behavioral check list to evaluate the severe behavioral disorder in 3-22 year old individuals. It has 56 items in four subscales: Stereotyped Behaviors, Social Interaction, Communication and Developmental Disturbance, which rates each behavior in four levels. The internal consistency of the subscales is reported as 0.90, 0.93, 0.89, 0.88, respectively, and the total score was considered reliable using Chronbach’s Alpha (0.96). The construct reliability of the questionnaire was correlated with the Autism Behavior Checklist (ABC), 0.94 in totals, and 0.37-0.92 for their subscales [26].

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS)

Lovibond and Lovibond developed the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS) with 42 items to evaluate the symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress in adults [27]. The reliability of the depression, anxiety, and stress subscales was reported 0.91, 0.84, and 0.90, respectively. This is a diagnostic and concurrently valid questionnaire. Each subscale can be scored between 0-42.

Procedure

The present study had two phases; descriptive design at first to develop the plan followed by a semi-experimental pre-posttest research design with a control group for evaluation. In the initial phase, a large-scale field study was conducted over the existing therapeutic methods for children with autism. Then, 12 parents of autistic children were interviewed about their educational needs and problems in their own opinion. The techniques with approved efficacy in the research literature were incorporated based on the positive parenting structure and considering the counseling approach. Most of the techniques were selected from cognitive-behavioral therapy since the study population was the parents. Because they can understand their children and then take an active part in the treatment process through increasing their acceptance and capabilities. Both of the parents were encouraged to participate in the treatment process in this study, while previous studies suggested that usually one of the parents –especially the father- would be excluded. The researchers believed that this dual participation could enhance their marital adjustment and close relationship besides increasing their responsibility toward the treatment.

The final plan was developed from the initial incorporated plan after being evaluated, modified, and confirmed by four professionals in the field of autistic children through Delphi method. Table 1 shows the abstract of the parenting sessions in this study.

In this program, the sessions 4, 6, 8, and 13 were held separately for each couple with cognitive behavior approach, and sessions 14 and 15 were held for each family concentrating on the whole family with CBT approach. The family members were free to take part in these two sessions. Each absent parent would receive a brochure of the session to keep him or her in the process. All the sessions were conducted by a professional counselor or psychologist.

The second phase began right after developing the plan. As mentioned, the researchers designed a pre-posttest controlled trial for the clients who were referred to the rehabilitation centers in Tehran and who agreed and registered to participate. Twenty-six parents were selected among those registered, and were randomly assigned in two groups, control and experiment. All participants completed the questionnaires twice, once before starting the sessions, and once right after the end of the final session. The control group received no intervention regarding parent education at the time and had only the routine rehabilitative treatments.

Data analysis

Gilliam Autism Rating Scale has total score and four subscales. Differences of the subscale means between two groups were analyzed using Multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA). Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to analyze each subscale in pre-posttest, if the difference of total score was significant. Mean of GARS total score in posttest had been regarded as dependent variable and the covariate would be mean of total score in pretest, which would be examined by analysis of variance. Differences between mean of total score in DASS were analyzed by analysis of covariance considering mean of total score in pretest as the dependent variable, whereas mean of total score in posttest would be the covariate.

3. Results

Table 2 shows demographic information of the research sample. Independent t student results showed no significant difference between the two groups (P>0.05, t(24)=0.863). There was no significant difference in education (P>0.05, X2=1.114, df=3) and economic level (P>0.05, X2=0.644, df=2) between the two groups.

The variance-covariance matrices consistency (P<0.05), homogeneity of variances (P<0.05), and homogeneity of regression coefficients (P<0.05) were studied to test the first hypothesis and three basic assumptions of multivariate analysis of covariance. Results showed that these assumptions were set at 95 percent. The results of multivariate analysis of covariance showed that all four multivariate measures -Wilks’ Lambda, Pillai’s trace, Hotelling trace, and Roy’s largest root- are significant at the 99% confidence level (F(4,17)=5.690, P=0.004).

Thus, the null hypothesis is rejected and the linear combination of the four dependent variables shows that posttest components means -stereotyped behavior, communication, social interaction and development- were affected significantly by independent variable (Positive Parent Training Program), whereas the differences of four pretest means of the covariates have been eliminated. On the other hand, results suggested that the independent variable made reliable and significant changes on the means of four dependent variables in a linear combination. We used Analysis of Covariance to evaluate the effect of the independent variable on each dependent variable separately (Table 3).

According to Table 3, the experiment and control group did not significantly differ in terms of Stereotyped Behaviors (F(1,20)=4.30, P=0.053) and Development (F(1,20)=0.448, P=0.511) at 99% confidence level after eliminating the pretest effect. This indicated that the positive parent-training program did not statistically differ in its efficacy in reducing stereotyped behaviors and improving development of autistic children. On the contrary, the result of ANCOVA which eliminates the pretest effect, determines that this program could significantly change the means of communication (F(1,20)=10.07,

P=0.005 on 99% confidence level) and social interaction (F(1,20)=5.723, P=0.027 on 95% confidence level).

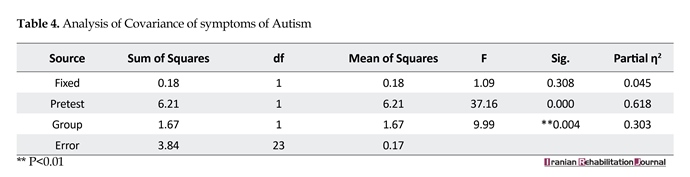

Since this study intended to evaluate the total effect of the training program on reducing autistic symptoms, thus the total score of GARS was used in analysis of covariance when the basic premises of ANCOVA (normal distribution, heterogeneity of variances, and homogeneity of gradients) were confirmed in the 99% confidence level. The result of this test indicates that the intervention in this study could significantly influence on the difference between the autistic symptoms in two groups. We can assume that considering η2=0.030, which shows the strength of the relationship of the experiment factor with the dependent variable, 31 percent of changes in the dependent variable were derived from the study intervention (Table 4).

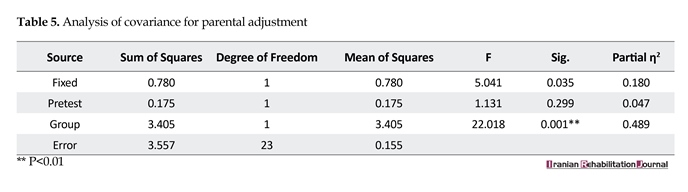

Analysis of covariance results suggested that the mean of total adjustment score differs between the two groups due to the study intervention (independent variable). It is concluded that considering the high eta square in this analysis (0.49), almost 49 percent of changes in the dependent variable (adjustment) are related to the intervention (positive parenting education) (Table 5).

4. Discussion

The main goal of this study was to develop a modulated program of parenting skills and to evaluate the effectiveness of this program in reducing autistic symptoms and increasing parental adjustment. Results indicated that the study intervention increased social interactions and facilitated relationships but had no significant effect on stereotyped behaviors and development. These findings are consistent to those of Sanders et al. [28], Sanders [29], Webster-Stratton et al. [30], Hoath and Sanders [31], Diament and Colletti [32], Connell et al. [33], Khorramabadi et al. [25], Talei [34], and Kheyrieh et al. [35] in the sense that educating the parents who have children with behavioral disorders could have significantly decreased their child’s behavioral problems. Whereas, Sanders [36] reported that parenting skills training could not reduce children’s behavioral problems in their study.

Since this study intended to evaluate the total effect of the training program on reducing autistic symptoms, thus the total score of GARS was used in analysis of covariance when the basic premises of ANCOVA (normal distribution, heterogeneity of variances, and homogeneity of gradients) were confirmed in the 99% confidence level. The result of this test indicates that the intervention in this study could significantly influence on the difference between the autistic symptoms in two groups. We can assume that considering η2=0.030, which shows the strength of the relationship of the experiment factor with the dependent variable, 31 percent of changes in the dependent variable were derived from the study intervention (Table 4).

Analysis of covariance results suggested that the mean of total adjustment score differs between the two groups due to the study intervention (independent variable). It is concluded that considering the high eta square in this analysis (0.49), almost 49 percent of changes in the dependent variable (adjustment) are related to the intervention (positive parenting education) (Table 5).

4. Discussion

The main goal of this study was to develop a modulated program of parenting skills and to evaluate the effectiveness of this program in reducing autistic symptoms and increasing parental adjustment. Results indicated that the study intervention increased social interactions and facilitated relationships but had no significant effect on stereotyped behaviors and development. These findings are consistent to those of Sanders et al. [28], Sanders [29], Webster-Stratton et al. [30], Hoath and Sanders [31], Diament and Colletti [32], Connell et al. [33], Khorramabadi et al. [25], Talei [34], and Kheyrieh et al. [35] in the sense that educating the parents who have children with behavioral disorders could have significantly decreased their child’s behavioral problems. Whereas, Sanders [36] reported that parenting skills training could not reduce children’s behavioral problems in their study.

Markus et al. (1997) believed that increasing parents’ awareness is one of the most important reasons of reducing children’s behavioral problems. If parents lack the knowledge of how to deal with their autistic child’s bizarre or aggressive behavior, they will be confused and/or angry and have dysfunctional reactions that may cause more behavior disorders [37]. For example, if parents understand that their child’s sensitivity toward change is not his/her problem only, and accept it, they can play an effective role in reducing such disorders and incompatibilities. Dale et al. [38] explained that if parents acquired enough skills in confronting children’s problematic behaviors, they would react more efficiently, which might lead to better results. Landa (2007) noted that there is a higher chance of predicting the future status in clients and reducing the children’s maladaptive and problematic behaviors through educating communication skills. In fact, they think that early adequate interventions are the key to improving communication skills and reduction of abnormal manners [38].

Quil (2000) indicated that packs imaginary cards have significantly increased communication skills in autistic children [37]. This finding supports the present study result as the researchers explained the effectiveness of these cards to the parents and provided some samples for them in order to teach them how to create the cards suitable for their own children. It seems that one of the important reasons of the ineffectiveness of the parenting skills program on stereotyped behavior in children was the counseling approach, which was the basis of this training program, whereas there was an essential need for occupational therapists’ professional cooperation in this regard. Perhaps this can be a matter of consideration in future studies.

The present study demonstrated that the positive parenting program is definitely useful in enhancing parental adjustment. This is consistent to the results of Sanders et al. [28], Connell et al. [33], and Zubrick et al. [39]. The main finding of this study confirms on fathers’ attending in the sessions on their therapeutic role. Although some fathers could not attend in the sessions because of their work, as long as they studied the brochures, it was implied that they had the tendency to support their family and participate in the group. However, common experiences with other parents and the idea of not being the only one with this problem are the group effects, which can heal their stress and sorrow [6]. Individual therapeutic sessions helped couples to understand, accept, and support each other.

Quil (2000) indicated that packs imaginary cards have significantly increased communication skills in autistic children [37]. This finding supports the present study result as the researchers explained the effectiveness of these cards to the parents and provided some samples for them in order to teach them how to create the cards suitable for their own children. It seems that one of the important reasons of the ineffectiveness of the parenting skills program on stereotyped behavior in children was the counseling approach, which was the basis of this training program, whereas there was an essential need for occupational therapists’ professional cooperation in this regard. Perhaps this can be a matter of consideration in future studies.

The present study demonstrated that the positive parenting program is definitely useful in enhancing parental adjustment. This is consistent to the results of Sanders et al. [28], Connell et al. [33], and Zubrick et al. [39]. The main finding of this study confirms on fathers’ attending in the sessions on their therapeutic role. Although some fathers could not attend in the sessions because of their work, as long as they studied the brochures, it was implied that they had the tendency to support their family and participate in the group. However, common experiences with other parents and the idea of not being the only one with this problem are the group effects, which can heal their stress and sorrow [6]. Individual therapeutic sessions helped couples to understand, accept, and support each other.

There are some labels for the parents with autistic children such as icehouse mothers, which means they failed to bring up their children. These labels make the family feel ashamed and socially isolated along with the fear and anxiety they experience regarding the judgments of the nonprofessional others; labels they believe in sometimes. It is obvious that the more the parents are aware of their children’s signs and symptoms, the more capable they will be in dealing with the judgments and sarcasm, which lead to a better feeling toward their child’s treatment. Nevertheless these stigmas will be added to the other stressors of the parents to make everything more difficult for them [40].

Masturn (2001) noted that most of the families with autistic children confronted with continuous and frequent stress and anxieties in their daily living [40]. Turnbull and Turnbull (1990) believed that autism affects the family as a whole. The decline in social replication and/or capability of coordination with others in such families may lead to depression and distress [37]. Kraus & Meazaros [41] explained that multiple disabilities cause limitations not only for the affected person but also for the entire family. When a family with an autistic child comes to public, it is possible for them to be ashamed of their child’s bizarre behavior. Some insipient people may blame the parents of such children. These reactions can cause separation defense mechanism in the family [37]. Sometimes the family could be nervous and angry even in understanding their child’s correct diagnosis [42]. The parents’ anxiety, stress, and depression exacerbated more and more since the diagnostic process is time consuming and there is no certain and distinguished treatment for this disorder [43].

Grief is a natural reaction of the parents who have lost a lot of plans and desires they had for their child all at once and been disappointed aftermath [44, 45]. Rutter (1997) said that the chronicity of autism make parents try continuously whereas they feel guilty and angry to see their child’s developmental delay [37]. The families with an autistic child feel frustrated and incompetent because of having an abnormal child. They have a sense of failure since it is not possible to live their life in the way they want. This grief is the basis of anxiety. Parents’ depression and sorrow get worse in some occasions like birthdays, graduation and marriage of their normal children [2].

Weiss showed that if the parent education program can increase their flexibility, then it would possibly improve their adjustment. Mierau suggested that positive interactions in the educational program might help with better adjustment for the parents. The family will learn how to eliminate the stressors and somehow reduce their stress and anxiety [37]. Meanwhile, participating in a group helps parents feel free of the loneliness and depression, and be calm because of the group empathy.

5. Conclusion

The modulated program of parenting skills presented in this study could empower parents and families of autistic children. It was effective on reducing the autistic symptoms with respect to social interaction and relationships as well as improving marital adjustment in such families. Thus the application of this compiled parenting program is recommended in caring for autistic children.

Acknowledgments

This is the report of a research project in collaboration with Research Institute of Education: Iranian Ministry of Education (Contract: 900.84.51 during 2011-2014). The project has been evaluated and approved for the ethical considerations by Research Institute for Exceptional Children.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

[1]McStay RL, Dissanayake C, Scheeren A, Koot HM, Begeer S. Parenting stress and autism: The role of age, autism severity, quality of life and problem behaviour of children and adolescents with autism. Autism. 2014; 18(5):502-10. doi: 10.1177/1362361313485163

[2]Weiss MJ. Hardiness and social support as predictors of stress in mothers of typical children, children with autism, and children with mental retardation. Autism. 2002; 6(1):115-30. doi: 10.1177/1362361302006001009

[3]Bailey D, Powell T. Assessing the information needs of families in early intervention. In: Guralnick MJ, editor. A Developmental Systems Approach to Early Intervention Baltimore. Towson, Maryland: Brookes Publishing Co; 2005.

[4]Shields J. The NAS Early bird programme: Partnership with parents in early intervention. Autism. 2001; 5(1):49-56. doi: 10.1177/1362361301051005

[5]Phoenix SS. Children with autism in Taiwan and the United States: Parental stress, parent-child relationships, and the reliability of a child development inventory [PhD dissertation]. Denton, Texas: University of North Texas; 2012.

[6]Samadi SA, McConkey R, Kelly G. Enhancing parental well-being and coping through a family-centred short course for Iranian parents of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2013; 17(1):27-43. doi: 10.1177/1362361311435156

[7]Naseef R, Freedman B. A diagnosis of Autism is not a prognosis of divorce. Autism Advocate. 2012; 9-14.

[8]Montes G, Halterman JS. Psychological functioning and coping among mothers of children with autism: A population-based study. PEDIATRICS. 2007; 119(5):e1040-e6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2819

[9]Benson PR, Karlof KL. Anger, stress proliferation, and depressed mood among parents of children with ASD: A longitudinal replication. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009; 39(2):350-62. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0632-0

[10]Hartley SL, Barker ET, Seltzer MM, Floyd F, Greenberg J, Orsmond G, et al. The relative risk and timing of divorce in families of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010; 24(4):449-57. doi: 10.1037/a0019847

[11]Khoshabi K, editor. [The adjustment mechanisms in parents with autistic child (Persian)]. Paper presented at: The 5th National Conference on Children Intellectual Disability. 22 November 2005. Tehran, Iran.

[12]Abbott A. Love in the time of autism. Psychology Today. 2013; 46(4):60-7.

[13]McConkey R, Truesdale‐Kennedy M, Crawford H, McGreevy E, Reavey M, Cassidy A. Preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders: evaluating the impact of a home‐based intervention to promote their communication. Early Child Development and Care. 2010; 180(3):299-315. doi: 10.1080/03004430801899187

[14]Keen D, Couzens D, Muspratt S, Rodger S. The effects of a parent-focused intervention for children with a recent diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder on parenting stress and competence. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2010; 4(2):229-41. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2009.09.009

[15]Higgins DJ, Bailey SR, Pearce JC. Factors associated with functioning style and coping strategies of families with a child with an autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2005; 9(2):125-37. doi: 10.1177/1362361305051403

[16]McCabe H. The beginnings of inclusion in the People’s Republic of China. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities. 2003; 28(1):16-22. doi: 10.2511/rpsd.28.1.16

[17]McCabe H, Huiping T. Early Intervention for Children with Autism in the People’s Republic of China: A Focus on Parent Training. Journal of International Special Needs Education. 2001; 4:39-43.

[18]Kuhn JC, Carter AS. Maternal self‐efficacy and associated parenting cognitions among mothers of children with autism. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006; 76(4):564-75. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.4.564

[19]Matson ML, Mahan S, Matson JL. Parent training: A review of methods for children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2009; 3(4):868-75. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2009.02.003

[20]Taylor B. Vaccines and the changing epidemiology of autism. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2006; 32(5):511-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00655.x

[21]Bregman JD. Definitions and characteristics of the spectrum. Autism spectrum disorders: Identification, Education, and Treatment. 2005; 3:3-46.

[22]Golabi P, Alipour A, Zandi B. [The effect of intervention by ABA method on children with autism (Persian)]. Journal of Exceptional Children. 2005; 5(1):33-54.

[23]JalaliMoghadam N, Pouretemad HR, Sedghpor BS, KhoShabi K, Chimeh N. [Parents of children with pervasive developmental disorders and their coping strategies (Persian)]. Journal of Family Research. 2007; 3(12):761-74.

[24]Chimeh N, Pouretemad HR, Khorramabadi R. [Need assessment of mothers with Autistic children (Persian)]. Journal of Family Research. 2008; 3(11):697-707.

[25]Khorramabadi R, Pouretemad H, Tahmasian K, Chimeh N. [A comparative study of parental stress in mothers of autistic and non autistic children (Persian)]. Journal of Family Research. 2009; 5(19):387-99.

[26]Lecavalier L. An evaluation of the Gilliam autism rating scale. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2005; 35(6):795–805. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-0025-6

[27]Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1995; 33(3):335-43. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u

[28]Sanders MR, Markie-Dadds C, Tully LA, Bor W. The triple P-positive parenting program: a comparison of enhanced, standard, and self-directed behavioral family intervention for parents of children with early onset conduct problems. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2000; 68(4):624-40. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.4.624

[29]Sanders MR. New directions in behavioral family intervention with children. In: Blechman E, Campbell SB, Rapoport JL, Routh DK, Rutter M, Werry JS, editors. Advances in Clinical Child Psychology. Berlin: Springer; 1996.

[30]Webster-Stratton C, Reid MJ, Hammond M. Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: Intervention outcomes for parent, child, and teacher training. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004; 33(1):105-24. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3301_11

[31]Hoath FE, Sanders MR. A feasibility study of Enhanced Group Triple P—positive parenting program for parents of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Behaviour Change. 2002; 19(4):191-206. doi: 10.1375/bech.19.4.191

[32]Diament C, Colletti G. Evaluation of behavioral group counseling for parents of learning-disabled children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1978; 6(3):385-400. doi: 10.1007/bf00924741

[33]Connell S, Sanders MR, Markie-Dadds C. Self-directed behavioral family intervention for parents of oppositional children in rural and remote areas. Behavior Modification. 1997; 21(4):379-408. doi: 10.1177/01454455970214001

[34]Talei A. [The effect of positive parenting program on behavior problems in girls and their mothers’ parental efficacy (Persian)] [MSc. thesis]. Tehran: Shahid Beheshti University; 2009.

[35]Kheirie M, Shaeiri MR, Azad Fallah P, Rasulzade Tabatabaei K. [Effect of the triple P-positive parenting program on children with oppositional defiant disorder (Persian)]. Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2009; 3(1):53-58.

[36]Sanders MR. Development, evaluation, and multinational dissemination of the Triple P-Positive Parenting Program. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2012; 8(1):345-79. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143104

[37]Mierau LJA. Emerging resilience in a family affected by autism [MSc. thesis]. Saskatchewan: University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon; 2008.

[38]Reffert LA. Autism education and early intervention: What experts recommend and how parents and public schools provide [PhD dissertation]. Toledo: University of Toledo; 2008.

[39]Zubrick SR, Silburn SR, Garton A, Burton PR, Dalby R, Carlton J et al. Western Australian child health survey: developing health and well-being in the nineties. Perth (WA): Australian Bureau of Statistics and the TVW Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, 1995.

[40]Wnoroski AK. Uncovering the stigma in parents of children with Autism [MSc. thesis]. Miami: Miami University; 2008.

[41]Krausz M, Meszaros J. The Retrospective Experiences of a Mother of a Child with Autism. International Journal of Special Education. 2005; 20(2):36-46.

[42]Sivberg B. Coping strategies and parental attitudes, a comparison of parents with children with autistic spectrum disorders and parents with non-autistic children. International Journal of Circumpolar Health. 2002; 61(sup2):36-50. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v61i0.17501

[43]Dale E, Jahoda A, Knott F. Mothers’ attributions following their child’s diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorder: Exploring links with maternal levels of stress, depression and expectations about their child’s future. Autism. 2006; 10(5):463-79. doi: 10.1177/1362361306066600

[44]Fernańdez-Alcántara M, García-Caro MP, Pérez-Marfil MN, Hueso-Montoro C, Laynez-Rubio C, Cruz-Quintana F. Feelings of loss and grief in parents of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2016; 55:312–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2016.05.007

[45]Solomon AH, Chung B. Understanding autism: How family therapists can support parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Family Process. 2012; 51(2):250-64. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01399.x

Masturn (2001) noted that most of the families with autistic children confronted with continuous and frequent stress and anxieties in their daily living [40]. Turnbull and Turnbull (1990) believed that autism affects the family as a whole. The decline in social replication and/or capability of coordination with others in such families may lead to depression and distress [37]. Kraus & Meazaros [41] explained that multiple disabilities cause limitations not only for the affected person but also for the entire family. When a family with an autistic child comes to public, it is possible for them to be ashamed of their child’s bizarre behavior. Some insipient people may blame the parents of such children. These reactions can cause separation defense mechanism in the family [37]. Sometimes the family could be nervous and angry even in understanding their child’s correct diagnosis [42]. The parents’ anxiety, stress, and depression exacerbated more and more since the diagnostic process is time consuming and there is no certain and distinguished treatment for this disorder [43].

Grief is a natural reaction of the parents who have lost a lot of plans and desires they had for their child all at once and been disappointed aftermath [44, 45]. Rutter (1997) said that the chronicity of autism make parents try continuously whereas they feel guilty and angry to see their child’s developmental delay [37]. The families with an autistic child feel frustrated and incompetent because of having an abnormal child. They have a sense of failure since it is not possible to live their life in the way they want. This grief is the basis of anxiety. Parents’ depression and sorrow get worse in some occasions like birthdays, graduation and marriage of their normal children [2].

Weiss showed that if the parent education program can increase their flexibility, then it would possibly improve their adjustment. Mierau suggested that positive interactions in the educational program might help with better adjustment for the parents. The family will learn how to eliminate the stressors and somehow reduce their stress and anxiety [37]. Meanwhile, participating in a group helps parents feel free of the loneliness and depression, and be calm because of the group empathy.

5. Conclusion

The modulated program of parenting skills presented in this study could empower parents and families of autistic children. It was effective on reducing the autistic symptoms with respect to social interaction and relationships as well as improving marital adjustment in such families. Thus the application of this compiled parenting program is recommended in caring for autistic children.

Acknowledgments

This is the report of a research project in collaboration with Research Institute of Education: Iranian Ministry of Education (Contract: 900.84.51 during 2011-2014). The project has been evaluated and approved for the ethical considerations by Research Institute for Exceptional Children.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

[1]McStay RL, Dissanayake C, Scheeren A, Koot HM, Begeer S. Parenting stress and autism: The role of age, autism severity, quality of life and problem behaviour of children and adolescents with autism. Autism. 2014; 18(5):502-10. doi: 10.1177/1362361313485163

[2]Weiss MJ. Hardiness and social support as predictors of stress in mothers of typical children, children with autism, and children with mental retardation. Autism. 2002; 6(1):115-30. doi: 10.1177/1362361302006001009

[3]Bailey D, Powell T. Assessing the information needs of families in early intervention. In: Guralnick MJ, editor. A Developmental Systems Approach to Early Intervention Baltimore. Towson, Maryland: Brookes Publishing Co; 2005.

[4]Shields J. The NAS Early bird programme: Partnership with parents in early intervention. Autism. 2001; 5(1):49-56. doi: 10.1177/1362361301051005

[5]Phoenix SS. Children with autism in Taiwan and the United States: Parental stress, parent-child relationships, and the reliability of a child development inventory [PhD dissertation]. Denton, Texas: University of North Texas; 2012.

[6]Samadi SA, McConkey R, Kelly G. Enhancing parental well-being and coping through a family-centred short course for Iranian parents of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2013; 17(1):27-43. doi: 10.1177/1362361311435156

[7]Naseef R, Freedman B. A diagnosis of Autism is not a prognosis of divorce. Autism Advocate. 2012; 9-14.

[8]Montes G, Halterman JS. Psychological functioning and coping among mothers of children with autism: A population-based study. PEDIATRICS. 2007; 119(5):e1040-e6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2819

[9]Benson PR, Karlof KL. Anger, stress proliferation, and depressed mood among parents of children with ASD: A longitudinal replication. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009; 39(2):350-62. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0632-0

[10]Hartley SL, Barker ET, Seltzer MM, Floyd F, Greenberg J, Orsmond G, et al. The relative risk and timing of divorce in families of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010; 24(4):449-57. doi: 10.1037/a0019847

[11]Khoshabi K, editor. [The adjustment mechanisms in parents with autistic child (Persian)]. Paper presented at: The 5th National Conference on Children Intellectual Disability. 22 November 2005. Tehran, Iran.

[12]Abbott A. Love in the time of autism. Psychology Today. 2013; 46(4):60-7.

[13]McConkey R, Truesdale‐Kennedy M, Crawford H, McGreevy E, Reavey M, Cassidy A. Preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders: evaluating the impact of a home‐based intervention to promote their communication. Early Child Development and Care. 2010; 180(3):299-315. doi: 10.1080/03004430801899187

[14]Keen D, Couzens D, Muspratt S, Rodger S. The effects of a parent-focused intervention for children with a recent diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder on parenting stress and competence. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2010; 4(2):229-41. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2009.09.009

[15]Higgins DJ, Bailey SR, Pearce JC. Factors associated with functioning style and coping strategies of families with a child with an autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2005; 9(2):125-37. doi: 10.1177/1362361305051403

[16]McCabe H. The beginnings of inclusion in the People’s Republic of China. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities. 2003; 28(1):16-22. doi: 10.2511/rpsd.28.1.16

[17]McCabe H, Huiping T. Early Intervention for Children with Autism in the People’s Republic of China: A Focus on Parent Training. Journal of International Special Needs Education. 2001; 4:39-43.

[18]Kuhn JC, Carter AS. Maternal self‐efficacy and associated parenting cognitions among mothers of children with autism. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006; 76(4):564-75. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.4.564

[19]Matson ML, Mahan S, Matson JL. Parent training: A review of methods for children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2009; 3(4):868-75. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2009.02.003

[20]Taylor B. Vaccines and the changing epidemiology of autism. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2006; 32(5):511-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00655.x

[21]Bregman JD. Definitions and characteristics of the spectrum. Autism spectrum disorders: Identification, Education, and Treatment. 2005; 3:3-46.

[22]Golabi P, Alipour A, Zandi B. [The effect of intervention by ABA method on children with autism (Persian)]. Journal of Exceptional Children. 2005; 5(1):33-54.

[23]JalaliMoghadam N, Pouretemad HR, Sedghpor BS, KhoShabi K, Chimeh N. [Parents of children with pervasive developmental disorders and their coping strategies (Persian)]. Journal of Family Research. 2007; 3(12):761-74.

[24]Chimeh N, Pouretemad HR, Khorramabadi R. [Need assessment of mothers with Autistic children (Persian)]. Journal of Family Research. 2008; 3(11):697-707.

[25]Khorramabadi R, Pouretemad H, Tahmasian K, Chimeh N. [A comparative study of parental stress in mothers of autistic and non autistic children (Persian)]. Journal of Family Research. 2009; 5(19):387-99.

[26]Lecavalier L. An evaluation of the Gilliam autism rating scale. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2005; 35(6):795–805. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-0025-6

[27]Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1995; 33(3):335-43. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u

[28]Sanders MR, Markie-Dadds C, Tully LA, Bor W. The triple P-positive parenting program: a comparison of enhanced, standard, and self-directed behavioral family intervention for parents of children with early onset conduct problems. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2000; 68(4):624-40. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.4.624

[29]Sanders MR. New directions in behavioral family intervention with children. In: Blechman E, Campbell SB, Rapoport JL, Routh DK, Rutter M, Werry JS, editors. Advances in Clinical Child Psychology. Berlin: Springer; 1996.

[30]Webster-Stratton C, Reid MJ, Hammond M. Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: Intervention outcomes for parent, child, and teacher training. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004; 33(1):105-24. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3301_11

[31]Hoath FE, Sanders MR. A feasibility study of Enhanced Group Triple P—positive parenting program for parents of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Behaviour Change. 2002; 19(4):191-206. doi: 10.1375/bech.19.4.191

[32]Diament C, Colletti G. Evaluation of behavioral group counseling for parents of learning-disabled children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1978; 6(3):385-400. doi: 10.1007/bf00924741

[33]Connell S, Sanders MR, Markie-Dadds C. Self-directed behavioral family intervention for parents of oppositional children in rural and remote areas. Behavior Modification. 1997; 21(4):379-408. doi: 10.1177/01454455970214001

[34]Talei A. [The effect of positive parenting program on behavior problems in girls and their mothers’ parental efficacy (Persian)] [MSc. thesis]. Tehran: Shahid Beheshti University; 2009.

[35]Kheirie M, Shaeiri MR, Azad Fallah P, Rasulzade Tabatabaei K. [Effect of the triple P-positive parenting program on children with oppositional defiant disorder (Persian)]. Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2009; 3(1):53-58.

[36]Sanders MR. Development, evaluation, and multinational dissemination of the Triple P-Positive Parenting Program. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2012; 8(1):345-79. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143104

[37]Mierau LJA. Emerging resilience in a family affected by autism [MSc. thesis]. Saskatchewan: University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon; 2008.

[38]Reffert LA. Autism education and early intervention: What experts recommend and how parents and public schools provide [PhD dissertation]. Toledo: University of Toledo; 2008.

[39]Zubrick SR, Silburn SR, Garton A, Burton PR, Dalby R, Carlton J et al. Western Australian child health survey: developing health and well-being in the nineties. Perth (WA): Australian Bureau of Statistics and the TVW Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, 1995.

[40]Wnoroski AK. Uncovering the stigma in parents of children with Autism [MSc. thesis]. Miami: Miami University; 2008.

[41]Krausz M, Meszaros J. The Retrospective Experiences of a Mother of a Child with Autism. International Journal of Special Education. 2005; 20(2):36-46.

[42]Sivberg B. Coping strategies and parental attitudes, a comparison of parents with children with autistic spectrum disorders and parents with non-autistic children. International Journal of Circumpolar Health. 2002; 61(sup2):36-50. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v61i0.17501

[43]Dale E, Jahoda A, Knott F. Mothers’ attributions following their child’s diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorder: Exploring links with maternal levels of stress, depression and expectations about their child’s future. Autism. 2006; 10(5):463-79. doi: 10.1177/1362361306066600

[44]Fernańdez-Alcántara M, García-Caro MP, Pérez-Marfil MN, Hueso-Montoro C, Laynez-Rubio C, Cruz-Quintana F. Feelings of loss and grief in parents of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2016; 55:312–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2016.05.007

[45]Solomon AH, Chung B. Understanding autism: How family therapists can support parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Family Process. 2012; 51(2):250-64. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01399.x

Article type: Original Research Articles |

Received: 2017/07/9 | Accepted: 2017/10/29 | Published: 2018/03/1

Received: 2017/07/9 | Accepted: 2017/10/29 | Published: 2018/03/1

References

1. McStay RL, Dissanayake C, Scheeren A, Koot HM, Begeer S. Parenting stress and autism: The role of age, autism severity, quality of life and problem behaviour of children and adolescents with autism. Autism. 2014; 18(5):502-10. doi: 10.1177/1362361313485163 [DOI:10.1177/1362361313485163]

2. Weiss MJ. Hardiness and social support as predictors of stress in mothers of typical children, children with autism, and children with mental retardation. Autism. 2002; 6(1):115-30. doi: 10.1177/1362361302006001009 [DOI:10.1177/1362361302006001009]

3. Bailey D, Powell T. Assessing the information needs of families in early intervention. In: Guralnick MJ, editor. A Developmental Systems Approach to Early Intervention Baltimore. Towson, Maryland: Brookes Publishing Co; 2005.

4. Shields J. The NAS Early bird programme: Partnership with parents in early intervention. Autism. 2001; 5(1):49-56. doi: 10.1177/1362361301051005 [DOI:10.1177/1362361301051005]

5. Phoenix SS. Children with autism in Taiwan and the United States: Parental stress, parent-child relationships, and the reliability of a child development inventory [PhD dissertation]. Denton, Texas: University of North Texas; 2012.

6. Samadi SA, McConkey R, Kelly G. Enhancing parental well-being and coping through a family-centred short course for Iranian parents of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2013; 17(1):27-43. doi: 10.1177/1362361311435156 [DOI:10.1177/1362361311435156]

7. Naseef R, Freedman B. A diagnosis of Autism is not a prognosis of divorce. Autism Advocate. 2012; 9-14.

8. Montes G, Halterman JS. Psychological functioning and coping among mothers of children with autism: A population-based study. PEDIATRICS. 2007; 119(5):e1040-e6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2819 [DOI:10.1542/peds.2006-2819]

9. Benson PR, Karlof KL. Anger, stress proliferation, and depressed mood among parents of children with ASD: A longitudinal replication. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009; 39(2):350-62. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0632-0 [DOI:10.1007/s10803-008-0632-0]

10. Hartley SL, Barker ET, Seltzer MM, Floyd F, Greenberg J, Orsmond G, et al. The relative risk and timing of divorce in families of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010; 24(4):449-57. doi: 10.1037/a0019847 [DOI:10.1037/a0019847]

11. Khoshabi K, editor. [The adjustment mechanisms in parents with autistic child (Persian)]. Paper presented at: The 5th National Conference on Children Intellectual Disability. 22 November 2005. Tehran, Iran.

12. Abbott A. Love in the time of autism. Psychology Today. 2013; 46(4):60-7.

13. McConkey R, Truesdale‐Kennedy M, Crawford H, McGreevy E, Reavey M, Cassidy A. Preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders: evaluating the impact of a home‐based intervention to promote their communication. Early Child Development and Care. 2010; 180(3):299-315. doi: 10.1080/03004430801899187 [DOI:10.1080/03004430801899187]

14. Keen D, Couzens D, Muspratt S, Rodger S. The effects of a parent-focused intervention for children with a recent diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder on parenting stress and competence. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2010; 4(2):229-41. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2009.09.009 [DOI:10.1016/j.rasd.2009.09.009]

15. Higgins DJ, Bailey SR, Pearce JC. Factors associated with functioning style and coping strategies of families with a child with an autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2005; 9(2):125-37. doi: 10.1177/1362361305051403 [DOI:10.1177/1362361305051403]

16. McCabe H. The beginnings of inclusion in the People's Republic of China. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities. 2003; 28(1):16-22. doi: 10.2511/rpsd.28.1.16 [DOI:10.2511/rpsd.28.1.16]

17. McCabe H, Huiping T. Early Intervention for Children with Autism in the People's Republic of China: A Focus on Parent Training. Journal of International Special Needs Education. 2001; 4:39-43.

18. Kuhn JC, Carter AS. Maternal self‐efficacy and associated parenting cognitions among mothers of children with autism. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006; 76(4):564-75. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.4.564 [DOI:10.1037/0002-9432.76.4.564]

19. Matson ML, Mahan S, Matson JL. Parent training: A review of methods for children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2009; 3(4):868-75. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2009.02.003 [DOI:10.1016/j.rasd.2009.02.003]

20. Taylor B. Vaccines and the changing epidemiology of autism. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2006; 32(5):511-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00655.x [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00655.x]

21. Bregman JD. Definitions and characteristics of the spectrum. Autism spectrum disorders: Identification, Education, and Treatment. 2005; 3:3-46.

22. Golabi P, Alipour A, Zandi B. [The effect of intervention by ABA method on children with autism (Persian)]. Journal of Exceptional Children. 2005; 5(1):33-54.

23. JalaliMoghadam N, Pouretemad HR, Sedghpor BS, KhoShabi K, Chimeh N. [Parents of children with pervasive developmental disorders and their coping strategies (Persian)]. Journal of Family Research. 2007; 3(12):761-74.

24. Chimeh N, Pouretemad HR, Khorramabadi R. [Need assessment of mothers with Autistic children (Persian)]. Journal of Family Research. 2008; 3(11):697-707.

25. Khorramabadi R, Pouretemad H, Tahmasian K, Chimeh N. [A comparative study of parental stress in mothers of autistic and non autistic children (Persian)]. Journal of Family Research. 2009; 5(19):387-99.

26. Lecavalier L. An evaluation of the Gilliam autism rating scale. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2005; 35(6):795–805. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-0025-6 [DOI:10.1007/s10803-005-0025-6]

27. Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1995; 33(3):335-43. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u [DOI:10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U]

28. Sanders MR, Markie-Dadds C, Tully LA, Bor W. The triple P-positive parenting program: a comparison of enhanced, standard, and self-directed behavioral family intervention for parents of children with early onset conduct problems. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2000; 68(4):624-40. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.4.624 [DOI:10.1037//0022-006X.68.4.624]

29. Sanders MR. New directions in behavioral family intervention with children. In: Blechman E, Campbell SB, Rapoport JL, Routh DK, Rutter M, Werry JS, editors. Advances in Clinical Child Psychology. Berlin: Springer; 1996. [DOI:10.1007/978-1-4613-0323-7_8]

30. Webster-Stratton C, Reid MJ, Hammond M. Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: Intervention outcomes for parent, child, and teacher training. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004; 33(1):105-24. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3301_11 [DOI:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_11]

31. Hoath FE, Sanders MR. A feasibility study of Enhanced Group Triple P—positive parenting program for parents of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Behaviour Change. 2002; 19(4):191-206. doi: 10.1375/bech.19.4.191 [DOI:10.1375/bech.19.4.191]

32. Diament C, Colletti G. Evaluation of behavioral group counseling for parents of learning-disabled children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1978; 6(3):385-400. doi: 10.1007/bf00924741 [DOI:10.1007/BF00924741]

33. Connell S, Sanders MR, Markie-Dadds C. Self-directed behavioral family intervention for parents of oppositional children in rural and remote areas. Behavior Modification. 1997; 21(4):379-408. doi: 10.1177/01454455970214001 [DOI:10.1177/01454455970214001]

34. Talei A. [The effect of positive parenting program on behavior problems in girls and their mothers' parental efficacy (Persian)] [MSc. thesis]. Tehran: Shahid Beheshti University; 2009.

35. Kheirie M, Shaeiri MR, Azad Fallah P, Rasulzade Tabatabaei K. [Effect of the triple P-positive parenting program on children with oppositional defiant disorder (Persian)]. Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2009; 3(1):53-58.

36. Sanders MR. Development, evaluation, and multinational dissemination of the Triple P-Positive Parenting Program. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2012; 8(1):345-79. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143104 [DOI:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143104]

37. Mierau LJA. Emerging resilience in a family affected by autism [MSc. thesis]. Saskatchewan: University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon; 2008.

38. Reffert LA. Autism education and early intervention: What experts recommend and how parents and public schools provide [PhD dissertation]. Toledo: University of Toledo; 2008.

39. Zubrick SR, Silburn SR, Garton A, Burton PR, Dalby R, Carlton J et al. Western Australian child health survey: developing health and well-being in the nineties. Perth (WA): Australian Bureau of Statistics and the TVW Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, 1995. [PMCID]

40. Wnoroski AK. Uncovering the stigma in parents of children with Autism [MSc. thesis]. Miami: Miami University; 2008.

41. Krausz M, Meszaros J. The Retrospective Experiences of a Mother of a Child with Autism. International Journal of Special Education. 2005; 20(2):36-46.

42. Sivberg B. Coping strategies and parental attitudes, a comparison of parents with children with autistic spectrum disorders and parents with non-autistic children. International Journal of Circumpolar Health. 2002; 61(sup2):36-50. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v61i0.17501 [DOI:10.3402/ijch.v61i0.17501]

43. Dale E, Jahoda A, Knott F. Mothers' attributions following their child's diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorder: Exploring links with maternal levels of stress, depression and expectations about their child's future. Autism. 2006; 10(5):463-79. doi: 10.1177/1362361306066600 [DOI:10.1177/1362361306066600]

44. Fernańdez-Alcántara M, García-Caro MP, Pérez-Marfil MN, Hueso-Montoro C, Laynez-Rubio C, Cruz-Quintana F. Feelings of loss and grief in parents of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2016; 55:312–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2016.05.007 [DOI:10.1016/j.ridd.2016.05.007]

45. Solomon AH, Chung B. Understanding autism: How family therapists can support parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Family Process. 2012; 51(2):250-64. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01399.x [DOI:10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01399.x]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |