Volume 16, Issue 3 (September 2018)

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2018, 16(3): 255-264 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ahadi H, Mokhlessin M. Persian Phonological Awareness Tests: A Comparative Analysis. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2018; 16 (3) :255-264

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-746-en.html

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-746-en.html

1- Institute for Humanities and Cultural Studies, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Speech Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran.

2- Department of Speech Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 570 kb]

(1621 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4227 Views)

Full-Text: (1574 Views)

1. Introduction

Reading is an essential component of academic learning and the basis of becoming an informed citizen [1]. Also, reading is the top national agenda [2]. Since the ease of learning to read and spell depends on our native language, the incidence of developmental dyslexia depends on the richness of the language. In particular, the incidence of dyslexia for speakers of alphabetic languages is between 5% to 15% [3]. This incidence rate in the Iranian primary school students is about 10% [4].

Phonological awareness is a metalinguistic ability by which children can recognize (and manipulate) individual sounds in oral language, and from words to syllables and phonemes. According to Everatt, phonological awareness is understanding the speech sounds regardless of their meanings [5]. However, others consider phonological awareness as a conscious mental and linguistic ability to recognize words and sounds [6]. This capability includes the ability to focus, manipulate, and think about the individual sounds in words.

This awareness consists of five levels which develop from the simplest to the most difficult one: Awareness of rhyme and alliteration in the words; Awareness of shared sounds within words; Ability to divide and blend syllables; Ability to segment phonemes; and Ability to manipulate phonemes [7]. Phonemic awareness is a skill to identify, segment, and combine phonemes into words. It is defined as the most difficult part of phonological awareness.

According to Smith and Simmons, phonemic awareness is made up of several components, including rhyme identification, segmentation, and phoneme deletion [8]. They believe that identification, phoneme combination, and phoneme segmentation are more important in learning to read. Studies showed that direct teaching of phonological awareness as well as direct training of alphabetic principles in preschool and school years, significantly increase children’s reading and spelling skills. Ryder and Tunmer stated that phonological awareness training leads to the development of decoding skills in dyslexic children [9].

Abilities related to phonological awareness like other cognitive linguistic processes have developmental natures. These abilities begin with general components and elements of language and sentences like words and ends with the phonological awareness of phonemes. It begins with language learning and lasts up to 9 years of age [10]. Prior research indicate that the awareness of the syllables develop at first, followed by awareness in words, such as rhyme and alliteration and finally, development of the phoneme awareness occur [11]. In order to perform the phonological awareness tasks, children need to have a phonological awareness system that includes a powerful representation of phonemes in the language.

There is a direct and bilateral correlation between reading and phonemic awareness. Phonemic awareness is critical for learning to read, and in return, reading helps improve phonemic awareness. In other words, some aspects of phonological awareness develop before reading instruction while others are developed after learning reading skills. The effect of phonological deficits on reading greatly depends on people’s native languages. In alphabetic languages like English, individual spoken sounds are represented by individual letters or groups of letters. To read and spell in alphabetic languages, a young child should learn the complex rules by which these letters and sounds relate to each other. In languages with non-alphabetic orthography like Chinese, there is no need to breaking words down into individual phonemes. Phonological impairments can cause greater difficulties in alphabetic languages than logographic languages [3]. Studies indicate that phonological awareness is essential in literacy and the development of reading and writing skills. This capability is so important that some children, especially the poor readers may never attain qualification for complex phoneme manipulation tasks.

Yopp demonstrated a comparison study consisting of 10 phonological awareness tests on kindergarten children [12]. He administered recognition of sound and words with the same initial phoneme, recognition and production of rhyme, sound isolation, phoneme segmentation, phoneme counting, phoneme deletion, specifying deleted phoneme, phoneme reversal, and invented spelling tasks. He reported that most study phonological awareness tasks were significantly correlated with each other, therefore they could be used for measuring the same construct.

Robelo compared three phonological awareness tools [13]. These tests were used to identify phonemic awareness deficits in kindergarten children. He found that using a standardized battery is more beneficial than using a screening measure. Stanovich and Cunningham assessed phonological awareness in kindergarten children to compare the task [14]. They recruited 49 subjects (25 males and 24 females) from three kindergartens. They found that several subjects could not substitute initial consonant and rhyme tasks and had random responses or semantic associates rather than concentrating on rhymes. Apparently there were wide varieties of tasks employed to assessing the same ability.

Cassano and Steiner assessed demands and task supports in early childhood phonological awareness tests, for better understanding of phonological awareness assessments [15]. They found considerable variability in the cognitive demands on phonological awareness assessments and concluded that we can increase or decrease the complexity of the tasks by making variations in response format and task support/demand.

Considering the importance of phonological awareness in teaching reading and writing of the Persian language, a comprehensive test to assess these skills in children seems necessary.

In Persian, there are two tests available to assess these skills; one visual phonological awareness test for children of 5 to 8 years old designed by Soleymani and Dastjerdi Kazemi [16], and one auditory phonological awareness test for 5 to 6 year old children designed by Arani Kashani and Ghorbani [17]. For the ease of comparison, the Soleymani and Dastjerdi Kazemi and Arani Kashani and Ghorbani tests were labeled as the visual test and the auditory test, respectively [16, 17]. As each test has special subtests and uses different modality and both are used for children aged 5 to 6, this study aimed to determine if typically developing preschool students perform similarly on the different subtest of these two tests. In this regard, we analyze the variability of the phonological awareness of different tests and their effects on the final score, in the present study.

Phonological awareness tests

We can measure phonological awareness in different ways. These measurements differ with respect to the linguistic unit analyzed (phoneme, syllable and word), position of manipulation in the linguistic elements (e.g., initial, medial or final), type of the manipulation in the task (detection, segmentation, deletion or production), mode of response (verbal, non-verbal) and also support and demands in performance (having an image and using of words or nonwords). This study will examine the strengths and weaknesses of these tests with the use of some of these factors and comparing the results in children.

Visual test

The visual test contains 10 subtests for assessing different areas of phonological awareness [16]. These subtests include segmenting (syllables, phoneme), recognizing (alliteration, rhyme, words with the same initial phoneme or same final phoneme), combination (phoneme), as well as naming and deleting (final, middle and initial phonemes). Each subset has 10 items. All items contain images.

The frequency of words are taken into consideration and to increase the validity of the test, the words vary from familiar to unfamiliar, with low to high frequency. This is a visual test, therefore, depictable words are used. To run the test, examiners show the pictures to the subjects, without labeling them. If the participants had difficulty labeling them, then the examiner only mentions the label. At the beginning of the test, 20 to 30 images are provided to make the participant familiar with their labels. Words and images used in different parts of the test have been chosen from the first grade Persian books, and other related sources. In choosing the words, the number of syllables and type of phonemes have also been noted. In syllable awareness subtest, 1, 2, 3, and 4 syllable words were used. The reliability of the subscales of the test was 0.84 to 0.96 and the validity of the test was 0.56 to 0.60 [16].

Auditory test

This test has three parts of syllable awareness, rhyme awareness, and phonemic awareness. The syllable awareness consists of syllable segmenting, combining, and deleting. The rhyme section has two subtests of rhyme recognition and saying rhyming words. In rhyme recognition subtest, the participants should recognize the monosyllabic words with different endings. Phonemic awareness includes subtest of phoneme recognition (recognition of the word with different initial phoneme, recognition of first phoneme in the words, recognition of final phoneme of the words) and saying the phoneme (saying the first phoneme of words and saying the words with the same first phoneme).

Since the designer believed that kindergarten children are not mature enough for responding to the phoneme combination and segmentation tasks, the test lacked these tasks. The test includes instructions and some examples for practicing each subtest. The test developer tried selecting the words from the all possible syllable structures in Persian for each of the 1-4 syllable words. In selecting the structures and required words for syllables and syllable deletion task, 1-2 syllable words were used. For this purpose, the test developer tried his best to choose different words and structures. Each subtest task is set from simple to complex. The reliability of the subscales is 0.85 to 0.96 and validity of the test is 0.76 to 0.97 [17].

2. Methods

This cross-sectional study included 40 normal preschool children (19 girls and 21 boys) in Tehran, Iran. Their Mean±SD age was 70.35±4.105 months. An experimental design was used to select the samples. Kindergarten children were selected randomly. First, four kindergartens in Tehran City (north, south, west and east part) were selected, then 10 subjects were randomly selected from each center. The phonological awareness tests were used for the assessments. The obtained data were analyzed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, Pearson correlation coefficient, the Independent t test and Paired t-test using SPSS V. 20.

The inclusion criteria consisted of lacking any auditory, visual, mental, neurological and physical deficiencies and being Persian monolingual. This information was obtained based on the child’s school records, interviews with teachers, parents and speech therapist (researcher). The data were collected in the first half of the school year (2016-2017).

The visual phonological awareness test was conducted, in one session. We only used 5 subtests (segmenting syllables, recognizing alliteration, rhyming, words with the same initial phoneme and words with the same final phoneme, combination of phonemes), because based on the test manual, only these subtests are applicable for the children aged 5 to 6 years. For each subtest of visual test, two exercises were initially performed, and then main tasks were presented. The subtest of auditory test was conducted in a separate session. Both tests were carried out after obtaining the written consent from the child’s parents. It took approximately 60 minutes to administer these two tests, for each child.

The participants’ performance was recorded. One mark was added to the total score for each correct answer. Then, the total score and the score of each subtest in the two tests were determined and analyzed by SPSS. First the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test used to evaluate the normal distribution of the data. Then descriptive statistics of phonological awareness tests were analyzed. The comparison of the total scores between boys and girls and between the two tests were done by the Independent t test and Paired t test, respectively. The relationship between variables was estimated by

Reading is an essential component of academic learning and the basis of becoming an informed citizen [1]. Also, reading is the top national agenda [2]. Since the ease of learning to read and spell depends on our native language, the incidence of developmental dyslexia depends on the richness of the language. In particular, the incidence of dyslexia for speakers of alphabetic languages is between 5% to 15% [3]. This incidence rate in the Iranian primary school students is about 10% [4].

Phonological awareness is a metalinguistic ability by which children can recognize (and manipulate) individual sounds in oral language, and from words to syllables and phonemes. According to Everatt, phonological awareness is understanding the speech sounds regardless of their meanings [5]. However, others consider phonological awareness as a conscious mental and linguistic ability to recognize words and sounds [6]. This capability includes the ability to focus, manipulate, and think about the individual sounds in words.

This awareness consists of five levels which develop from the simplest to the most difficult one: Awareness of rhyme and alliteration in the words; Awareness of shared sounds within words; Ability to divide and blend syllables; Ability to segment phonemes; and Ability to manipulate phonemes [7]. Phonemic awareness is a skill to identify, segment, and combine phonemes into words. It is defined as the most difficult part of phonological awareness.

According to Smith and Simmons, phonemic awareness is made up of several components, including rhyme identification, segmentation, and phoneme deletion [8]. They believe that identification, phoneme combination, and phoneme segmentation are more important in learning to read. Studies showed that direct teaching of phonological awareness as well as direct training of alphabetic principles in preschool and school years, significantly increase children’s reading and spelling skills. Ryder and Tunmer stated that phonological awareness training leads to the development of decoding skills in dyslexic children [9].

Abilities related to phonological awareness like other cognitive linguistic processes have developmental natures. These abilities begin with general components and elements of language and sentences like words and ends with the phonological awareness of phonemes. It begins with language learning and lasts up to 9 years of age [10]. Prior research indicate that the awareness of the syllables develop at first, followed by awareness in words, such as rhyme and alliteration and finally, development of the phoneme awareness occur [11]. In order to perform the phonological awareness tasks, children need to have a phonological awareness system that includes a powerful representation of phonemes in the language.

There is a direct and bilateral correlation between reading and phonemic awareness. Phonemic awareness is critical for learning to read, and in return, reading helps improve phonemic awareness. In other words, some aspects of phonological awareness develop before reading instruction while others are developed after learning reading skills. The effect of phonological deficits on reading greatly depends on people’s native languages. In alphabetic languages like English, individual spoken sounds are represented by individual letters or groups of letters. To read and spell in alphabetic languages, a young child should learn the complex rules by which these letters and sounds relate to each other. In languages with non-alphabetic orthography like Chinese, there is no need to breaking words down into individual phonemes. Phonological impairments can cause greater difficulties in alphabetic languages than logographic languages [3]. Studies indicate that phonological awareness is essential in literacy and the development of reading and writing skills. This capability is so important that some children, especially the poor readers may never attain qualification for complex phoneme manipulation tasks.

Yopp demonstrated a comparison study consisting of 10 phonological awareness tests on kindergarten children [12]. He administered recognition of sound and words with the same initial phoneme, recognition and production of rhyme, sound isolation, phoneme segmentation, phoneme counting, phoneme deletion, specifying deleted phoneme, phoneme reversal, and invented spelling tasks. He reported that most study phonological awareness tasks were significantly correlated with each other, therefore they could be used for measuring the same construct.

Robelo compared three phonological awareness tools [13]. These tests were used to identify phonemic awareness deficits in kindergarten children. He found that using a standardized battery is more beneficial than using a screening measure. Stanovich and Cunningham assessed phonological awareness in kindergarten children to compare the task [14]. They recruited 49 subjects (25 males and 24 females) from three kindergartens. They found that several subjects could not substitute initial consonant and rhyme tasks and had random responses or semantic associates rather than concentrating on rhymes. Apparently there were wide varieties of tasks employed to assessing the same ability.

Cassano and Steiner assessed demands and task supports in early childhood phonological awareness tests, for better understanding of phonological awareness assessments [15]. They found considerable variability in the cognitive demands on phonological awareness assessments and concluded that we can increase or decrease the complexity of the tasks by making variations in response format and task support/demand.

Considering the importance of phonological awareness in teaching reading and writing of the Persian language, a comprehensive test to assess these skills in children seems necessary.

In Persian, there are two tests available to assess these skills; one visual phonological awareness test for children of 5 to 8 years old designed by Soleymani and Dastjerdi Kazemi [16], and one auditory phonological awareness test for 5 to 6 year old children designed by Arani Kashani and Ghorbani [17]. For the ease of comparison, the Soleymani and Dastjerdi Kazemi and Arani Kashani and Ghorbani tests were labeled as the visual test and the auditory test, respectively [16, 17]. As each test has special subtests and uses different modality and both are used for children aged 5 to 6, this study aimed to determine if typically developing preschool students perform similarly on the different subtest of these two tests. In this regard, we analyze the variability of the phonological awareness of different tests and their effects on the final score, in the present study.

Phonological awareness tests

We can measure phonological awareness in different ways. These measurements differ with respect to the linguistic unit analyzed (phoneme, syllable and word), position of manipulation in the linguistic elements (e.g., initial, medial or final), type of the manipulation in the task (detection, segmentation, deletion or production), mode of response (verbal, non-verbal) and also support and demands in performance (having an image and using of words or nonwords). This study will examine the strengths and weaknesses of these tests with the use of some of these factors and comparing the results in children.

Visual test

The visual test contains 10 subtests for assessing different areas of phonological awareness [16]. These subtests include segmenting (syllables, phoneme), recognizing (alliteration, rhyme, words with the same initial phoneme or same final phoneme), combination (phoneme), as well as naming and deleting (final, middle and initial phonemes). Each subset has 10 items. All items contain images.

The frequency of words are taken into consideration and to increase the validity of the test, the words vary from familiar to unfamiliar, with low to high frequency. This is a visual test, therefore, depictable words are used. To run the test, examiners show the pictures to the subjects, without labeling them. If the participants had difficulty labeling them, then the examiner only mentions the label. At the beginning of the test, 20 to 30 images are provided to make the participant familiar with their labels. Words and images used in different parts of the test have been chosen from the first grade Persian books, and other related sources. In choosing the words, the number of syllables and type of phonemes have also been noted. In syllable awareness subtest, 1, 2, 3, and 4 syllable words were used. The reliability of the subscales of the test was 0.84 to 0.96 and the validity of the test was 0.56 to 0.60 [16].

Auditory test

This test has three parts of syllable awareness, rhyme awareness, and phonemic awareness. The syllable awareness consists of syllable segmenting, combining, and deleting. The rhyme section has two subtests of rhyme recognition and saying rhyming words. In rhyme recognition subtest, the participants should recognize the monosyllabic words with different endings. Phonemic awareness includes subtest of phoneme recognition (recognition of the word with different initial phoneme, recognition of first phoneme in the words, recognition of final phoneme of the words) and saying the phoneme (saying the first phoneme of words and saying the words with the same first phoneme).

Since the designer believed that kindergarten children are not mature enough for responding to the phoneme combination and segmentation tasks, the test lacked these tasks. The test includes instructions and some examples for practicing each subtest. The test developer tried selecting the words from the all possible syllable structures in Persian for each of the 1-4 syllable words. In selecting the structures and required words for syllables and syllable deletion task, 1-2 syllable words were used. For this purpose, the test developer tried his best to choose different words and structures. Each subtest task is set from simple to complex. The reliability of the subscales is 0.85 to 0.96 and validity of the test is 0.76 to 0.97 [17].

2. Methods

This cross-sectional study included 40 normal preschool children (19 girls and 21 boys) in Tehran, Iran. Their Mean±SD age was 70.35±4.105 months. An experimental design was used to select the samples. Kindergarten children were selected randomly. First, four kindergartens in Tehran City (north, south, west and east part) were selected, then 10 subjects were randomly selected from each center. The phonological awareness tests were used for the assessments. The obtained data were analyzed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, Pearson correlation coefficient, the Independent t test and Paired t-test using SPSS V. 20.

The inclusion criteria consisted of lacking any auditory, visual, mental, neurological and physical deficiencies and being Persian monolingual. This information was obtained based on the child’s school records, interviews with teachers, parents and speech therapist (researcher). The data were collected in the first half of the school year (2016-2017).

The visual phonological awareness test was conducted, in one session. We only used 5 subtests (segmenting syllables, recognizing alliteration, rhyming, words with the same initial phoneme and words with the same final phoneme, combination of phonemes), because based on the test manual, only these subtests are applicable for the children aged 5 to 6 years. For each subtest of visual test, two exercises were initially performed, and then main tasks were presented. The subtest of auditory test was conducted in a separate session. Both tests were carried out after obtaining the written consent from the child’s parents. It took approximately 60 minutes to administer these two tests, for each child.

The participants’ performance was recorded. One mark was added to the total score for each correct answer. Then, the total score and the score of each subtest in the two tests were determined and analyzed by SPSS. First the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test used to evaluate the normal distribution of the data. Then descriptive statistics of phonological awareness tests were analyzed. The comparison of the total scores between boys and girls and between the two tests were done by the Independent t test and Paired t test, respectively. The relationship between variables was estimated by

the Pearson correlation coefficient. The validity and reliability of both tests were confirmed.

3. Results

Phonological awareness progresses from vocabulary level to individual sound level. There are variety of tasks and tools to measure phonological awareness skills in young children (e.g. rhyming, segmentation, blending tasks, etc.). Speech-language pathologists and researchers need to know their differences. There are two published diagnostic tests available in Persian that can be used for assessing phonological awareness skills in children. These tests have different types of tasks, although being designed to measure the same construct. This study aimed to compare the phonological awareness ability of Persian monolingual children in these two tests, in which, one has visual base and the other one has the auditory base.

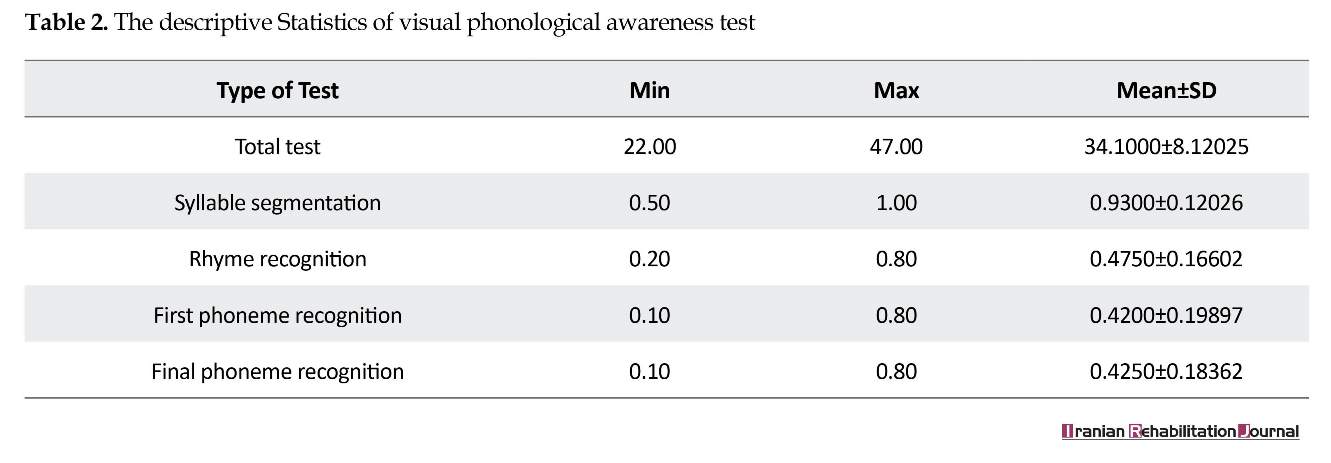

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test showed the normal distribution of the obtained data. Table 1 shows that there is no statistically significant difference between two groups. Descriptive statistics of the phonological awareness tests were analyzed and the results are presented in Tables 2 and 3. Table 2 lists the performances of 40 Persian children in the subtests of the visual phonological awareness test. Table 1 compared of total scores between boys and girls by the Independent t test. There was no significant difference in the mean scores of the two tests between the genders (Table 1), therefore group members are considered as integrated.

3. Results

Phonological awareness progresses from vocabulary level to individual sound level. There are variety of tasks and tools to measure phonological awareness skills in young children (e.g. rhyming, segmentation, blending tasks, etc.). Speech-language pathologists and researchers need to know their differences. There are two published diagnostic tests available in Persian that can be used for assessing phonological awareness skills in children. These tests have different types of tasks, although being designed to measure the same construct. This study aimed to compare the phonological awareness ability of Persian monolingual children in these two tests, in which, one has visual base and the other one has the auditory base.

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test showed the normal distribution of the obtained data. Table 1 shows that there is no statistically significant difference between two groups. Descriptive statistics of the phonological awareness tests were analyzed and the results are presented in Tables 2 and 3. Table 2 lists the performances of 40 Persian children in the subtests of the visual phonological awareness test. Table 1 compared of total scores between boys and girls by the Independent t test. There was no significant difference in the mean scores of the two tests between the genders (Table 1), therefore group members are considered as integrated.

As per the maximum score shown in Table 2, some children can perform syllable segmentation (max=1) and phoneme combination (max=1) completely in some subsets, and the minimum score shows that some children cannot perform the phoneme combination task (min=0). The highest and the lowest mean scores are respectively related to syllable segmentation and first phoneme recognition.

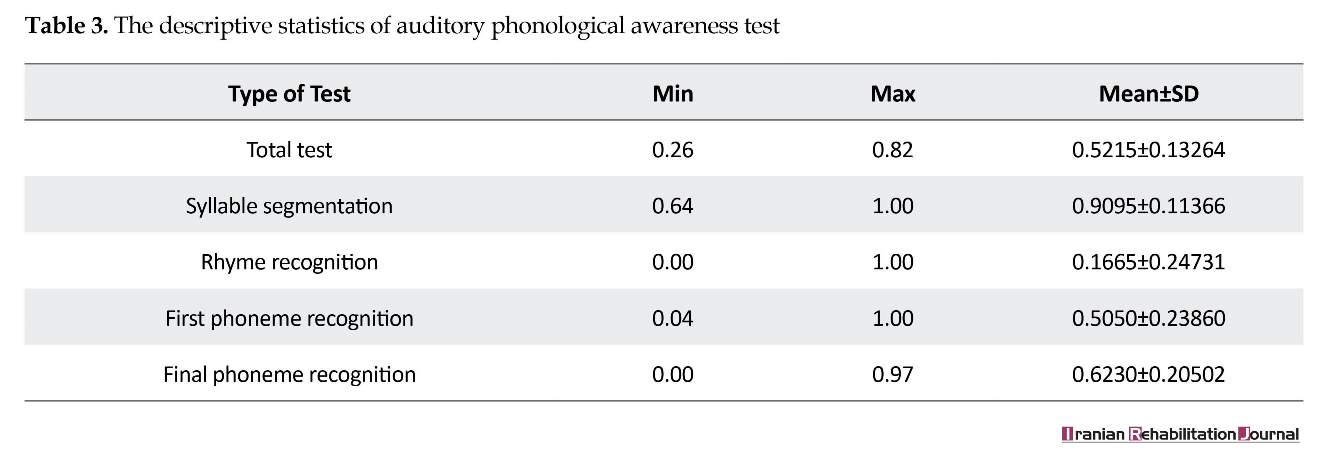

Table 3 presents the performances of subjects in the auditory phonological awareness test. Table 3 displays the mean scores, standard deviation, as well as minimum and maximum scores in the subtests of auditory phonological awareness test. According to the maximum score shown in Table 3, some children can perform syllable segmentation (max=1) and syllable combination (max=1) completely. And the minimum score shows that some children cannot perform the rhyme recognition task (min=0) and final phoneme recognition (min=0). The highest and the lowest mean scores are respectively related to syllable segmentation and rhyme articulation.

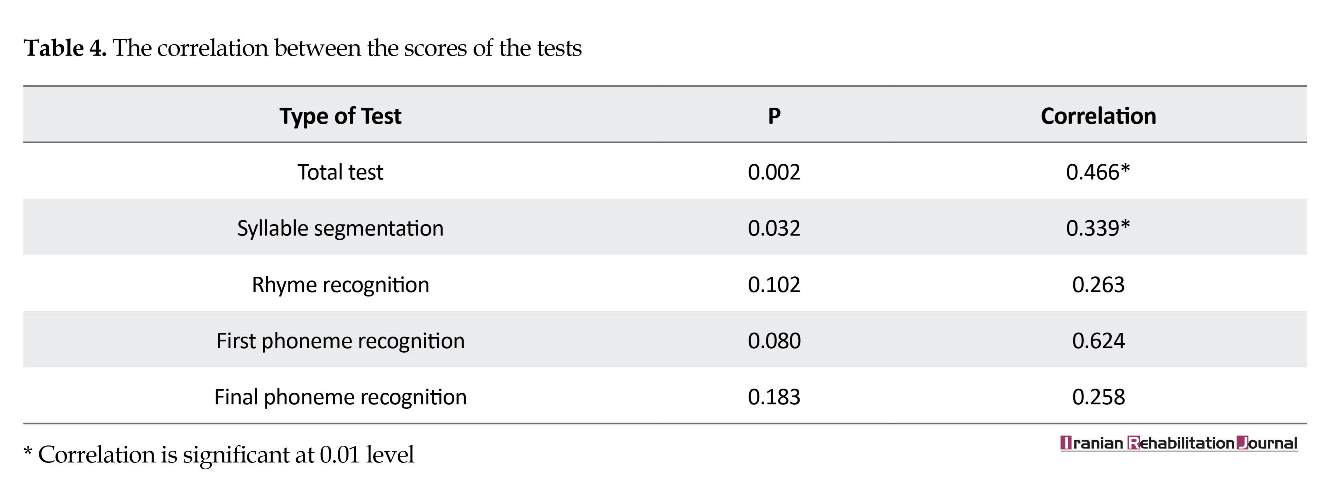

The relationship between the total and subtest scores of the tests were measured by comparing the total score of the phonological awareness tests and their subtests. Table 4 presents the correlation between the total scores of the tests and the correlated subtests of the tests. Based on Table 4, there are significant correlations between total scores (0.466) and syllable segmentation tasks (0.339). Paired t test was used to measure differences in the mean scores and results are presented in Table 5. Table 5 shows significant differences in the total scores (0.000) and some tasks such as rhyme recognition (0.000) and final phoneme recognition (0.000).

4. Discussion

According to the findings, in spite of significant differences in total scores (P<0.05) and some tasks such as rhyme recognition (P<0.05) and final phoneme recognition (P<0.05) of the tests, there were a positive correlation between the total scores (r=0.466) and the syllable segmentation tasks (r=0.339). The comparison of design in the two tests shows several common strong points in both tests. Both test tasks are arranged from simple to complex, both have paid attention to the structure and the number of syllables, as well as the phonemic features

Table 3 presents the performances of subjects in the auditory phonological awareness test. Table 3 displays the mean scores, standard deviation, as well as minimum and maximum scores in the subtests of auditory phonological awareness test. According to the maximum score shown in Table 3, some children can perform syllable segmentation (max=1) and syllable combination (max=1) completely. And the minimum score shows that some children cannot perform the rhyme recognition task (min=0) and final phoneme recognition (min=0). The highest and the lowest mean scores are respectively related to syllable segmentation and rhyme articulation.

The relationship between the total and subtest scores of the tests were measured by comparing the total score of the phonological awareness tests and their subtests. Table 4 presents the correlation between the total scores of the tests and the correlated subtests of the tests. Based on Table 4, there are significant correlations between total scores (0.466) and syllable segmentation tasks (0.339). Paired t test was used to measure differences in the mean scores and results are presented in Table 5. Table 5 shows significant differences in the total scores (0.000) and some tasks such as rhyme recognition (0.000) and final phoneme recognition (0.000).

4. Discussion

According to the findings, in spite of significant differences in total scores (P<0.05) and some tasks such as rhyme recognition (P<0.05) and final phoneme recognition (P<0.05) of the tests, there were a positive correlation between the total scores (r=0.466) and the syllable segmentation tasks (r=0.339). The comparison of design in the two tests shows several common strong points in both tests. Both test tasks are arranged from simple to complex, both have paid attention to the structure and the number of syllables, as well as the phonemic features

of the selected phonemes. Also two or three examples are provided for each subtest, in both tests.

The analysis revealed that children’s performance in different phonological awareness tests were not the same but still, correlated. Beside the total score, the correlation of some subtests such as the syllable segmentation, the rhyme recognition, and the first and final phoneme recognition was analyzed. The comparison of the two tests shows differences in different subtests in which syllable, word and phoneme awareness are assessed. The visual phonological awareness test lacks subtest of syllable identification, syllable combination, and syllable deleting. Thus, the auditory test is richer than the visual test in syllable awareness. Also, syllable segmentation subtest in visual test consists of ten tasks, including 5 two syllable words, 4 three syllable words and 1 four syllable word. But syllable segmentation subtest in auditory test contains 14 words and pseudowords consisting of two words of each number of syllables. Therefore, there is also a one syllable word that was challenging for the children.

While syllable segmentation in the auditory test begins with two syllable words, still single syllable recognition for the children is often problematic and this reduces the score of children’s response to this subtest. However, according to Table 4, the difference between these subtests is not significant.

In the phonemic awareness section, the number of subtests in the auditory test is less than the visual test because the developers of test believe the growth of phonological awareness in children aged 5 to 6 is very low. The visual test has several subtests for this section including phoneme segmentation, phoneme combination, and deleting the first and final phoneme of words. Thus, the common subtests between the two tests in phoneme awareness section are the identification of first phoneme and final phoneme, although their implementation is slightly different. For example, in the auditory test, the subjects should identify the phoneme of one word but in the visual test they should identify the words with the same first phoneme. According to Table 5, there is a significant difference in the total scores and the scores of some tasks such as rhyme recognition and final phoneme recognition.

Based on Table 4, there is a significant correlation in the subtests of syllable segmentation of the tests; therefore, the performance of participants is almost the same in these subtests of phonological awareness. But Table 5 shows a significant difference between the two tests. Such difference in their performance may be due to different knowledge demands of the tasks. Our findings are consistent with the findings of Bialystok which showed that the experiment was influenced by the tasks [18]. Different scores in the phonological awareness can be due to varieties in tasks, procedures, and measurement materials [19].

The visual test of the rhyme recognition subtest presented three words for each item, but the auditory test presented four words for each task. This can be the reason why the mean score of this task in the auditory test is lower than that in the visual test. There is a positive correlation between those results. It shows that better scores in the word awareness in the visual test are positively correlated with better scores in the auditory tests, but the level of difficulty is not the same in both tests. In addition, according to the mean score of rhyme identification subtests, recognizing the words with the same rhyme in the set of words (three words) is much easier than distinguishing the word with different rhyme in the set of words (four words).

Furthermore, the subjects should identify the word with different rhyme in the auditory test, but they should identify the words with the same rhyme in the visual test. This can be the possible explanation for the differences in the tasks and in the support and demands of performance, accordingly [13]. Comparing the results of two subtests in Tables 4 and 5 shows a significant difference between the results but they are correlated. In addition, as Table 4 shows, there is no significant correlation between the results of the subtests, so the children, with the highest scores in one task, do not necessarily obtain the highest scores in others. Also, higher mean score of this subtest indicates that the detection of one phoneme in a word is easier than identifying common phonemes in three words; therefore, the tasks of this subtest in the auditory test is easier than that in the visual test.

There is a major problem in the phoneme combination subtest in the visual test. In its subtests, the words come with images and children are able to identify the target word without combining the phonemes, by observing them and hearing the first phoneme. For example, children can identify /jaroo/, when hearing the phoneme /j/ because there are no other words beginning with this phoneme. Thus the performance of children in this task is related to the identification of first phoneme rather than phoneme combination.

Another important difference between these tests is that in many subtests of the auditory test, like syllable identification, syllable combination, and first and final phoneme identification, there are two separate sections; one of which is related to the non-word. However the visual test lacks this section because the developers believe that such tasks are not necessary and including them in the test can increase duration of performance and fatigue in children. Many studies like Shirazi [20] showed no differences between the pseudowords and the words correlation with reading levels.

The other major difference is the number of tasks in different subtests. All subtests of the visual test include 10 tasks, while the number of the tasks in subtests of the auditory test varies. The results showed that in spite of a significant difference between the two test scores, there was a significant correlation between them. Thus, it is not possible to compare the results of those.

Although the present study showed some advantages of the visual test over the auditory phonological awareness test, there are also some strong points in the auditory test because it contains some special extra tasks, needed in pre-school children. For example many foreign tests have non-word sections. It is assumed that both tests have strong and weak points and need some revision. Various elements may affect the complex process of phonological awareness, like the use of different tests or tasks [19]. Therefore, much attention is needed, in order to design tests for assessing phonological awareness, especially in selection of the tasks. However, to find more variables involved in phonological processing, further studies are required in different groups of preschool children.

5. Conclusion

Variations in response format and task demand can change complexity of the tasks, leading to different scores. Therefore, comparing the results of the two studies with different tests is not correct. However, we can consider their correlation with other skills, because of the correlation between their results.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

For the children participated in the study, consent and permission were obtained from their parents.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors certify that they have no affiliation with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial, or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials dismissed in this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my special gratitude to the directors of preschool centers, and all the people who assisted me in the course of this research.

References

The analysis revealed that children’s performance in different phonological awareness tests were not the same but still, correlated. Beside the total score, the correlation of some subtests such as the syllable segmentation, the rhyme recognition, and the first and final phoneme recognition was analyzed. The comparison of the two tests shows differences in different subtests in which syllable, word and phoneme awareness are assessed. The visual phonological awareness test lacks subtest of syllable identification, syllable combination, and syllable deleting. Thus, the auditory test is richer than the visual test in syllable awareness. Also, syllable segmentation subtest in visual test consists of ten tasks, including 5 two syllable words, 4 three syllable words and 1 four syllable word. But syllable segmentation subtest in auditory test contains 14 words and pseudowords consisting of two words of each number of syllables. Therefore, there is also a one syllable word that was challenging for the children.

While syllable segmentation in the auditory test begins with two syllable words, still single syllable recognition for the children is often problematic and this reduces the score of children’s response to this subtest. However, according to Table 4, the difference between these subtests is not significant.

In the phonemic awareness section, the number of subtests in the auditory test is less than the visual test because the developers of test believe the growth of phonological awareness in children aged 5 to 6 is very low. The visual test has several subtests for this section including phoneme segmentation, phoneme combination, and deleting the first and final phoneme of words. Thus, the common subtests between the two tests in phoneme awareness section are the identification of first phoneme and final phoneme, although their implementation is slightly different. For example, in the auditory test, the subjects should identify the phoneme of one word but in the visual test they should identify the words with the same first phoneme. According to Table 5, there is a significant difference in the total scores and the scores of some tasks such as rhyme recognition and final phoneme recognition.

Based on Table 4, there is a significant correlation in the subtests of syllable segmentation of the tests; therefore, the performance of participants is almost the same in these subtests of phonological awareness. But Table 5 shows a significant difference between the two tests. Such difference in their performance may be due to different knowledge demands of the tasks. Our findings are consistent with the findings of Bialystok which showed that the experiment was influenced by the tasks [18]. Different scores in the phonological awareness can be due to varieties in tasks, procedures, and measurement materials [19].

The visual test of the rhyme recognition subtest presented three words for each item, but the auditory test presented four words for each task. This can be the reason why the mean score of this task in the auditory test is lower than that in the visual test. There is a positive correlation between those results. It shows that better scores in the word awareness in the visual test are positively correlated with better scores in the auditory tests, but the level of difficulty is not the same in both tests. In addition, according to the mean score of rhyme identification subtests, recognizing the words with the same rhyme in the set of words (three words) is much easier than distinguishing the word with different rhyme in the set of words (four words).

Furthermore, the subjects should identify the word with different rhyme in the auditory test, but they should identify the words with the same rhyme in the visual test. This can be the possible explanation for the differences in the tasks and in the support and demands of performance, accordingly [13]. Comparing the results of two subtests in Tables 4 and 5 shows a significant difference between the results but they are correlated. In addition, as Table 4 shows, there is no significant correlation between the results of the subtests, so the children, with the highest scores in one task, do not necessarily obtain the highest scores in others. Also, higher mean score of this subtest indicates that the detection of one phoneme in a word is easier than identifying common phonemes in three words; therefore, the tasks of this subtest in the auditory test is easier than that in the visual test.

There is a major problem in the phoneme combination subtest in the visual test. In its subtests, the words come with images and children are able to identify the target word without combining the phonemes, by observing them and hearing the first phoneme. For example, children can identify /jaroo/, when hearing the phoneme /j/ because there are no other words beginning with this phoneme. Thus the performance of children in this task is related to the identification of first phoneme rather than phoneme combination.

Another important difference between these tests is that in many subtests of the auditory test, like syllable identification, syllable combination, and first and final phoneme identification, there are two separate sections; one of which is related to the non-word. However the visual test lacks this section because the developers believe that such tasks are not necessary and including them in the test can increase duration of performance and fatigue in children. Many studies like Shirazi [20] showed no differences between the pseudowords and the words correlation with reading levels.

The other major difference is the number of tasks in different subtests. All subtests of the visual test include 10 tasks, while the number of the tasks in subtests of the auditory test varies. The results showed that in spite of a significant difference between the two test scores, there was a significant correlation between them. Thus, it is not possible to compare the results of those.

Although the present study showed some advantages of the visual test over the auditory phonological awareness test, there are also some strong points in the auditory test because it contains some special extra tasks, needed in pre-school children. For example many foreign tests have non-word sections. It is assumed that both tests have strong and weak points and need some revision. Various elements may affect the complex process of phonological awareness, like the use of different tests or tasks [19]. Therefore, much attention is needed, in order to design tests for assessing phonological awareness, especially in selection of the tasks. However, to find more variables involved in phonological processing, further studies are required in different groups of preschool children.

5. Conclusion

Variations in response format and task demand can change complexity of the tasks, leading to different scores. Therefore, comparing the results of the two studies with different tests is not correct. However, we can consider their correlation with other skills, because of the correlation between their results.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

For the children participated in the study, consent and permission were obtained from their parents.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors certify that they have no affiliation with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial, or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials dismissed in this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my special gratitude to the directors of preschool centers, and all the people who assisted me in the course of this research.

References

- Koda K, Zehler AM. Learning to read across languages: Cross-linguistic relationships in first- and second-language literacy development. Routledge: Taylor & Francis; 2008.

- McGill Franzen A, Allington RL. Handbook of reading disability research. New York: Rout ledge; 2011.

- Brunswick N. Dyslexia: A beginner’s guide (Beginner’s guides). London: Oneworld Publications; 2012.

- Sedaghati, Foroughi R, Shafiei B, Maracy MR. Prevalence of dyslexia in first to fifth grade elementary students Isfahan, Iran. Bimonthly Audilogy. 2010; 19(1):94-101.

- Everatt J. Reading and dyslexia: Visual And attentional processes. Abingdon: Routledge; 1999.

- Bernthal, Bankson NW, Flipsen P. Articulation and phonological disorder: Speech sound disorders in children, 7th Edition. London: Pearson; 2013.

- Brunswick N. Dyslexia. London: Oneworld Publications; 2009.

- Smith SB, Simmons DC, Gleason MM, Kame’enui EJ, Baker SK, Sprick K, et al. An analysis of phonological awareness instruction in four kindergarten basal reading programs. Reading & Writing Quarterly. 2001; 17(1):25-51. [DOI:10.1080/105735601455729]

- Ryder JF, Tunmer WE, Greaney KT. Explicit instruction in phonemic awareness and phonemically based decoding skills as an intervention strategy for struggling readers in whole language classrooms. Reading and Writing. 2008; 21(4):349-69. [DOI:10.1007/s11145-007-9080-z]

- Yopp HK. Developing phonemic awareness in young children. The Reading Teacher. 1992; 45(9):696-703.

- Goswami U. Phonological representations, reading development and dyslexia: Towards cross-linguistic theoretical framework. Dyslexia. 2000; 6(2):133-51. [DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0909(200004/06)6:23.0.CO;2-A]

- Yopp HK. The validity and reliability of phonemic awareness tests. Reading Research Quarterly. 1988; 23(2):159-77.

- Robelo E. A Comparison of three phonological awareness tools used to identify phonemic awareness deficits in kindergarten-age children [PhD Dissertation]. Florida: University of Central Florida; 2006.

- Stanovich K, Cunningham AE. Assessing phonological awareness in kindergarten children: Issues of task comparability. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1984; 38(1):175-90. [DOI:10.1016/0022-0965(84)90120-6]

- Cassano CM, Steiner L. Exploring assessment demands and task supports in early childhood phonological awareness assessments. Literacy Research: Theory, Method, and Practice. 2016; 65(1):217-35.

- Soleymani Z Dastjerdi Kazemi M. Validity and reliability of the phonological awareness test. Journal of Psychology. 2005; 9(1):82-100.

- Ghorbani A, Arani Kashani Z. [Auditory test of phonological awareness skills (ASHA-5) for 5-6 years old Persian speaking children (Persian)]. Tehran: Setayesh Hasti; 2009.

- Bialystok ES, Majumder Sh, MARTIN MM. Developing phonological awareness: Is there a bilingual advantage? Applied Psycholinguistics. 2003; 24(1):27-44. [DOI:10.1017/S014271640300002X]

- Tunmer WE, Rohl M. Phonological awareness and reading acquisition. In: Tunmer WE, Rohl M, editors, Phonological Awareness in Reading. Berlin: Springer; 1991. [DOI:10.1007/978-1-4612-3010-6_1]

- Shirazi T. [Study and comparison between rapid naming and phoneme awareness in dyslexic and normal readers (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2004; 5(3):49-54.

Article type: Original Research Articles |

Subject:

Speech therapy

Received: 2018/01/28 | Accepted: 2018/06/2 | Published: 2018/09/1

Received: 2018/01/28 | Accepted: 2018/06/2 | Published: 2018/09/1

References

1. Koda K, Zehler AM. Learning to read across languages: Cross-linguistic relationships in first- and second-language literacy development. Routledge: Taylor & Francis; 2008.

2. McGill Franzen A, Allington RL. Handbook of reading disability research. New York: Rout ledge; 2011.

3. Brunswick N. Dyslexia: A beginner's guide (Beginner's guides). London: Oneworld Publications; 2012.

4. Sedaghati, Foroughi R, Shafiei B, Maracy MR. Prevalence of dyslexia in first to fifth grade elementary students Isfahan, Iran. Bimonthly Audilogy. 2010; 19(1):94-101.

5. Everatt J. Reading and dyslexia: Visual And attentional processes. Abingdon: Routledge; 1999. [PMID]

6. Bernthal, Bankson NW, Flipsen P. Articulation and phonological disorder: Speech sound disorders in children, 7th Edition. London: Pearson; 2013.

7. Brunswick N. Dyslexia. London: Oneworld Publications; 2009.

8. Smith SB, Simmons DC, Gleason MM, Kame'enui EJ, Baker SK, Sprick K, et al. An analysis of phonological awareness instruction in four kindergarten basal reading programs. Reading & Writing Quarterly. 2001; 17(1):25-51. [DOI:10.1080/105735601455729] [DOI:10.1080/105735601455729]

9. Ryder JF, Tunmer WE, Greaney KT. Explicit instruction in phonemic awareness and phonemically based decoding skills as an intervention strategy for struggling readers in whole language classrooms. Reading and Writing. 2008; 21(4):349-69. [DOI:10.1007/s11145-007-9080-z] [DOI:10.1007/s11145-007-9080-z]

10. Yopp HK. Developing phonemic awareness in young children. The Reading Teacher. 1992; 45(9):696-703.

11. Goswami U. Phonological representations, reading development and dyslexia: Towards cross-linguistic theoretical framework. Dyslexia. 2000; 6(2):133-51. [DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0909(200004/06)6:23.0.CO;2-A]

https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0909(200004/06)6:2<133::AID-DYS160>3.0.CO;2-A [DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0909(200004/06)6:23.0.CO;2-A]

12. Yopp HK. The validity and reliability of phonemic awareness tests. Reading Research Quarterly. 1988; 23(2):159-77. [DOI:10.2307/747800]

13. Robelo E. A Comparison of three phonological awareness tools used to identify phonemic awareness deficits in kindergarten-age children [PhD Dissertation]. Florida: University of Central Florida; 2006.

14. Stanovich K, Cunningham AE. Assessing phonological awareness in kindergarten children: Issues of task comparability. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1984; 38(1):175-90. [DOI:10.1016/0022-0965(84)90120-6] [DOI:10.1016/0022-0965(84)90120-6]

15. Cassano CM, Steiner L. Exploring assessment demands and task supports in early childhood phonological awareness assessments. Literacy Research: Theory, Method, and Practice. 2016; 65(1):217-35. [DOI:10.1177/2381336916661521]

16. Soleymani Z Dastjerdi Kazemi M. Validity and reliability of the phonological awareness test. Journal of Psychology. 2005; 9(1):82-100.

17. Ghorbani A, Arani Kashani Z. [Auditory test of phonological awareness skills (ASHA-5) for 5-6 years old Persian speaking children (Persian)]. Tehran: Setayesh Hasti; 2009.

18. Bialystok ES, Majumder Sh, MARTIN MM. Developing phonological awareness: Is there a bilingual advantage? Applied Psycholinguistics. 2003; 24(1):27-44. [DOI:10.1017/S014271640300002X] [DOI:10.1017/S014271640300002X]

19. Tunmer WE, Rohl M. Phonological awareness and reading acquisition. In: Tunmer WE, Rohl M, editors, Phonological Awareness in Reading. Berlin: Springer; 1991. [DOI:10.1007/978-1-4612-3010-6_1] [DOI:10.1007/978-1-4612-3010-6_1]

20. Shirazi T. [Study and comparison between rapid naming and phoneme awareness in dyslexic and normal readers (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2004; 5(3):49-54.

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |