Volume 18, Issue 3 (September 2020)

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2020, 18(3): 263-274 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Fathipour-Azar Z, Akbarfahimi M, Rabiei F. The Challenges of People With Heart Failure in Activity of Daily Living Performance: A Qualitative Study in Iranian Context. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2020; 18 (3) :263-274

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1081-en.html

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1081-en.html

1- Department of Occupational therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Rehabilitation Research center,Department of Occupational therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Rehabilitation Research center,Department of Occupational therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 698 kb]

(1492 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3265 Views)

The inclusion criteria consisted of having heart failure diagnosed by a cardiologist, having no neurological, psychiatric, or orthopedic diseases that affect heart function and ADL performance, MMSE (The Mini-Mental State Examination) score >21, being 36-65 years old and having Ejection Fraction (EF) >45% [23]. If any participant cannot provide the desired information, they were excluded from the study.

Data collection

The interviews were held in a quiet room in Rajai Hospital from June 2015 to December 2016 between 9 -12 AM. The selection of participants was with maximum diversity in culture, custom, age, level of education, and duration of heart failure to gather more extensive data. The first author recorded all interviews and transcribed verbatim. The beginning of all sessions accompanied by the designed guideline questions such as “What is your daily schedule?” “Are there any changes after your disease in the quality of your ADL performance?” “What are your limited activities?” and “ What factors have limited your activities?” The research team and expert panel created the interview guide. The expert panel consisted of four occupational therapists, two physical therapists, and one physician. The interviews ended with this question: Do you want to add more information? Finally, all participants were requested to review the transcript and confirm it. The interviews continued until data saturation. Sampling continued until no further information to extract.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using the Graneheim and Lundman method [22]. The first (F.Z) and fourth (A.B) authors were engaged in data analysis by reading the interviews several times line by line. Then the data were explored for meaning units. After abstracting the meaning units, codes, subcategories, and categories were extracted. At last, the underlying meanings were interpreted as themes. To achieve trustworthiness, the Lincoln and Guba approach was applied [24]. Through prolong engagement, the researcher spent enough time gathering data, and presenting the meaning units and initial codes to the research team for verification and feedback. Besides, investigator triangulation was utilized. One expert in qualitative research and one in occupational therapy checked data (expert check). Moreover, two colleagues who were involved in some other qualitative projects, commented on the emerged data as well (peer check). Finally, the transcriptions and codes were reviewed by the participants (member check).

Ethical approval

All participants signed informed consent before the interview and were aware of the aims of the project. The participants were permitted to withdraw from the study at any time and were guaranteed the confidentiality of their conversations. The ethical code of this study was approved by the Iran University of Medical Sciences (IR.IUMS.REC 1395.95-03-32- 28606).

3. Results

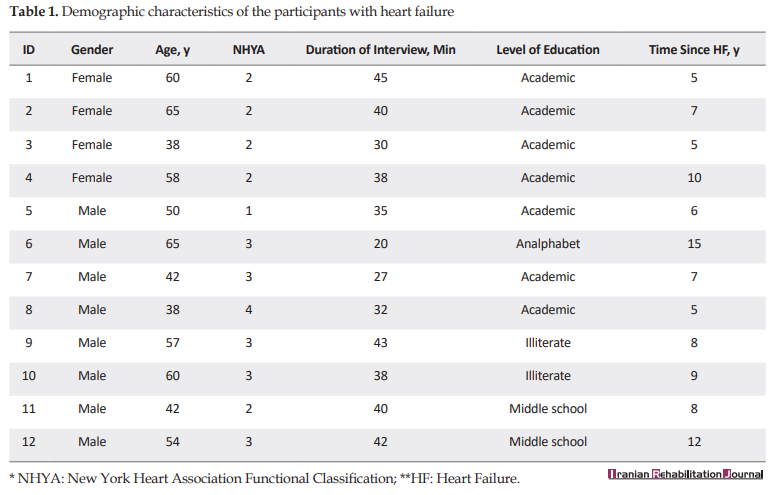

Twelve people with HF (4 females and 8 males) took part in this study. Each participant was interviewed to the point that data saturation was attained. The average interview time was 32.83 minutes ranging from 20 to 45 minutes. The demographic characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1.

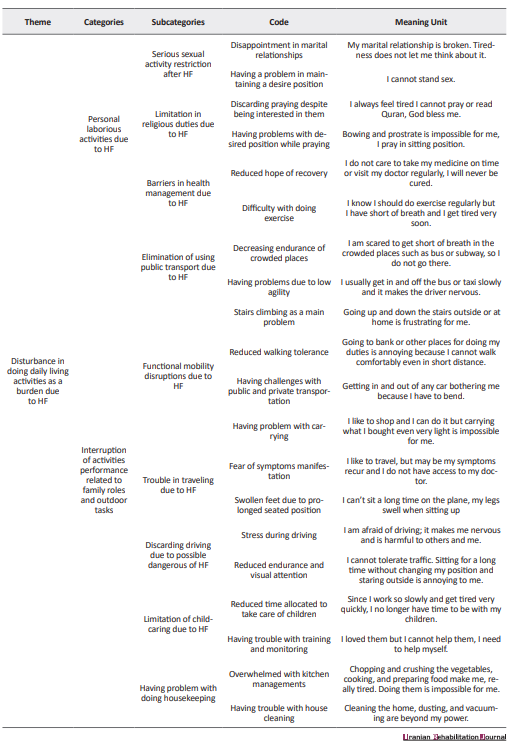

The participants explained their challenges during performing ADL. Based on the data analysis, 2 themes and 4 categories were extracted. The themes consisted of “obstacles preventing normal functioning due to HF” and “disturbances in doing daily living activities as a burden due to HF”. The first theme consisted of 2 categories and 8 subcategories. The categories of the first theme include interference of previous experience in performance (4 subcategories) and challenges during the performance (4 subcategories). The second theme consisted of 2 categories and 13 subcategories. The categories of the second theme are entitled to personal laborious activities due to HF (7 subcategories) and interruption of activities performance related to family roles and outdoor tasks (6 subcategories) (Table 2).

Obstacles preventing normal functioning due to HF

Interference of previous experience in performance

During the interview, the participants mentioned that their bad experiences interfere with their current performance and it scares them from doing it again. For instance, they did not do some activities at all because they are difficult, they have not to value for them, or they are frightened because of a lack of safety during performance-based on physician prescription, previous experience, or so on. Some of their claims are as follow:

“I don’t iron because I’m not interested in doing it” (P-3).

“To feel safe I prefer not to do vacuuming but I can do it” (P-2).

“I don’t trip more because I fear to experience breath shortness” (P-9).

Doing some activities, which are important for participants should be done by others or give them up because of their problem due to HF.

“I need someone to help me in all activities” (P-8).

“I can’t do some of my tasks and my children should help me” (P-2).

The participants stated that performing some activities are difficult for them and they try to substitute it or give up it.

“It is difficult for me to go up the stairs” (P-4)

Challenges during the performance

The participants complained of the recurrence of symptoms of HF during ADL. They pointed to pain, dyspnea, prolongation of doing the activities, and the most frequently the fatigue.

Pain: “When I want to bend I feel a sharp pain in my chest” (P-4)

Dyspnea: “I can’t go up the stairs because of difficulty in breathing” (P-11).

“When it gets cold or warm I can’t breathe properly” (P-12).

Time duration: “If I want to go outside it takes me a long time to get ready” (P-10).

Fatigue: “I want to vacuum and do my home duties but I become exhausted after a short time” (P-10).

“I am exhausted and get out of the bathroom soon. My bathing lasts for 2 minutes because I fear to find myself in a dangerous situation I feel something bad happens”(P-12).

Disturbance in doing daily living activities as a burden due to HF

The results of this study revealed that daily living disturbances due to HF have two main categories. The participants suffer from doing several activities and complain of some interfering factors related to HF during doing their daily activities.

Personal laborious activities due to HF

Performing activities of daily living, which are essential for survival is a basic need for all human beings. However, the participants of the current study encounter difficulties in defecation, dressing, grooming, bathing, doing religious duties, health management, and sexual activities. For example, descriptions of 4 participants were as follows:

“Toileting is difficult for me because of sitting and I suffer from defecation problems” (P-4).

“Due to abdominal swelling, one must help me get dressed and tying shoelaces “(P-8).

“I can’t see some part of my body in terms of personal hygiene (body grooming) during bending due to abdominal swelling and pressure” (P-6).

“Bathing is challenging for me because I can’t stand and move so I need to sit down on a chair” (P-7).

“I say my prayer in a sitting position because I feel chest pain during bending” (P-4).

Sexual activities are a problem and maintaining the desired posture is frustrating.

“Overall, I have no marital relationship with my wife. From the day, I was ill because it is difficult for me to maintain the desire position. I have no sense in this regard so that I have the energy to do this activity” (P-11).

Interruption of activities performance related to family roles and outdoor tasks

The participants stated mobility limitation in the community for doing activities such as shopping, financial management in the bank, and so on due to lack of energy and walking or carrying. Depending on one’s level of performance, simple activities like sitting in different vehicles or average levels activities such as transferring to the car, walking, fast walking, and complicated activities such as going up and down the stairs are disrupted. These problems limited them to participate in the community for doing outdoor family roles. In this regard, 3 participants’ descriptions were as follows:

“I cannot lift heavy things and I suffer from shortness of breath. My walking is very limited. I would rather go by car. When climbing the stairs, my heart starts pounding and I have to take a rest for half an hour. Shopping is difficult for me to buy 5 kg of fruit and take them home as if my heart is collapsed when it becomes heavy” (P-7).

“ If I want to walk fast, chest pain is started, I cannot carry heavy things, I want to be like a normal person, I love to go hiking, but if I want to be in a rush, I can’t and must walk slowly “ (P-5).

“Going up and down the stairs is hard, I can’t walk long” (P-4).

Besides, using public transportation such as bus and subway is overwhelming because of sitting or standing for a long time and staying in a crowded space.

“I got on the subway train once, but I couldn’t stay any longer “(P-10).

Travelling is impossible for these individuals due to the need to sit for long hours.

“I used to go to the north for two or three days, but now I cannot do that. It is difficult for me now. I do not know what will happen in the way during traveling and I worried that if I get sick what will happen. For example, once I wanted to go to the north and I became sick along the way and the ambulance came...”. (P-9).

Driving with a personal car is a code with low frequency.

“I cannot drive. I cannot do that now” (P-1).

Devoting some time of day for the interests of the children and accompanying them are among the things that are lost in these individuals.

“I become reticent and isolated. I cannot communicate very much with my children; I do not have any energy” (P-11).

Housekeeping was an important activity for most participants and is particularly impaired in some cases. They stated the problems with cleaning activities like sweeping, tidying up the beds, doing laundry, washing the floor, and ironing, as well as kitchen-related activities such as washing the dishes, cutting, and chopping vegetables, meat, cooking, and so on.

“I used to vacuum clean, but now I can’t. I get short of breath and my heartbeat doesn’t allow me to do so” (P-3).

“Chopping is unbearable for me” (P-2).

4. Discussion

The results of the current study demonstrated some common challenges of people who suffer from heart failure during performing their daily living activities. The participants clarified the type of involved activities and the form of these challenges, which clarify some new perspective of the extent of influence of HF on their lives and maybe on their wellbeing. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no qualitative study on this issue and current questionnaires do not address these challenges for Iranian people with HF. As an occupational therapist with a top-down approach, investigating the problematic activities of daily living is essential. The participants of the current study complained about the distributing effect of HF on their ADLs. It is worth noting that our participants did not have any challenges with cognitive functions (MMSE > 21) and their NHYA (New York Heart Association Functional Classification) ranged between I to IV. Therefore, their major challenges were due to physical problems caused exclusively by HF, and the people who suffer from dementia or other cognitive disorders with the secondary complication of all heart disease were not included in the current study. Based on their perspective, 2 themes were extracted: obstacles preventing normal functioning due to HF, and disturbance in doing daily living activities as a burden due to HF.

Obstacles preventing normal functioning due to HF have 2 categories: interference of previous experience in performance and challenges during the performance. It can be realized that HF affects all aspects of the participant’s life. For example, the participants did not have any challenges with eating but they declared that the quality of performance of all daily activities has had changed.

In some cases, the participants preferred not to perform some daily activities based on unsuccessful experiences of performance in the past, such as falling, chest pain, and fatigue. They declared that after HF, some activities have lost their value for them. The most frequent devalued activities, in this case, were driving and caring for others. It seems that deprivation from doing something that was once valued and now should not be done due to the complication of HF causes people to become depressed and disappointed.

Difficulty and safety are recognized as interlinked performance parameters. Difficulty in doing activities was another complaint of participants that lead them to seek help or giving up activities. In the current study, the most frequent difficult activities to perform were housekeeping, bathing, and functional mobility. These findings in some way are consistent with Dunlay et al. study results which introduced eating, toileting, and dressing as the easiest activities and stair climbing, walking, and housekeeping as the hardest ones [8]. Norberg et al. introduced that bathing in PADL and transportation and shopping in IADL were the hardest activities to perform in their study population [9].

Challenges during the performance of activities is another category in the obstacles preventing normal functioning due to HF. The chief complaint of the participants during the performance of all activities of daily living was the manifestation of chest pain, the prolonged time duration of activity performance, early onset of fatigue, and dyspnea. According to the most frequent comments of the participants, the greatest confounder performing activities in HF was fatigue and dyspnea. This finding is consistent with other studies that show the relationship between fatigue, shortness of breath, and chest pain with physical activities in people with HF [9]. However, fatigue and cognitive impairments are the most common complaint in a variety of diseases such as multiple sclerosis and stroke [25,26,27], which usually the common intervention is assistive devices prescription and teaching energy conservation techniques [9]. Therefore, empowering people with HF with these educations and helping them to coach performance problems due to fatigue is essential.

Regarding the second theme extracted from the interviews, in two categories, two types of challenging activities were explored: having personal laborious activities due to HF and interruption of activities performance related to family roles and outdoor tasks. Although all ADLs were recognized as meaningful activities, frequently performed, and as the most important view, they are essential for survival, our participants declared that personal activities are much more challenging than family role-related and outside home activities. They justified it in two dimensions. In one sight, while personal activities such as defection and bathing have more private nature, seeking help from others is embarrassing. In the other view, the independent performance of personal activity is strongly linked to the ability to live independently at home alone. However, efficient implementation of family roles and outside home activities are much more related to well-being. Therefore, the effort to carry out personal activities independently is greater in their view.

In the current study, challenging personal activates were defecation, dressing, grooming, bathing, sexual activity, religious duties, and health management. However, the challenging family role-related and outside home activities were using public transportation, functional mobility, traveling, driving, child caring, and housekeeping. Since there is no other qualitative research in this regard, we compared the limited activities of the result of the current study with two existing questionnaires PMADL-8 and DAQIHF developed for assessing the functional outcome of all types of HF.

The development of PMADL-8 was based on the ICF model and the items extracted from the review of other ADL questionnaires. The original version consisted of 40 activities (13 BADLs and 27 IADLs); the number of items was reduced by experts. The final version consisted of 8 activities, in which the psychometric characteristics were confirmed by 130 people with HF in Japan. The items included 1- getting up and off from the floor without instruments, 2- washing your body and hair, 3- going up a flight of stairs without a handrail, 4- vacuuming your room, 5- pulling and closing a heavy sliding door, 6- getting into and out of a car, 7- walking at the same speed with someone of the same age, and 8- walking up a slight slope for 10 min [16]. Although these items are the same as some activities of the challenging activities in the current study, nearly all items seem to focus on mobility and two items were dedicated only to walking. However, important positions such as squatting and bending, which are more frequently used in activities such as dressing, bathing, and toileting in the Iranian lifestyle were ignored. Besides some activities such as praying, grooming, or caring for others had not been included.

DAQIHF is another questionnaire for HF patients. This questionnaire like PMADL-8 was designed by reviewing the acceptable questionnaires and consisted of 82 activities in 7 dimensions, including problems in sleep and resting periods, washing, meals, toilet, household, and related activities, sport and non-sport leisure time activities [17]. These activities are not limited to ADL and other occupational domains were included and mainly were based on physical activity, so and they did not consider other aspects of performance outcomes of ADLs such as pain, safety, and so on.

The evidence in the present study confirms that the challenging activities in our participants are much broader than those mentioned in these two specialized questionnaires. For instance, spiritual issues and the need to do religious activities were noteworthy for many people suffering from debilitation diseases [28] and frequently mentioned by present participants but in these two special questionnaires for people with HF as a chronic disease, these activities were not included. Also, they announced that despite the need to have sex with their spouse they suppress themselves because of the HF problems.

5. Conclusion

HF is a chronic disease in which people with this problem should live with a wide spectrum of limitations in daily activities and tolerate some distributing factors that interfere with their performance. Therefore, exploring their needs and limitations for proper interventions to keep up their ability to perform ADL and live independently is essential. Previous studies confirm their limitations and two available assessments exist to evaluate the occupations of HF. However, some diversity of lifestyle and the effect of culture on ADL performance made us design this qualitative research for better understanding the special needs of people with HF in Iran. According to the findings of this study, people with HF experienced challenges during the performance of all areas of ADL related to themselves or their family roles and outside home duties. Their experiences of insecurity, dependency, and having difficulty strongly influenced their performances in new tasks or different situations. The performance outcomes such as pain, dyspnea, fatigue, and prolonged-time duration were the main confounder of performance in HF. Having a convenient assessment of ADLs for special disorders is fundamental [29]. It seems that developing a questionnaire for assessing ADL in people with HF with considering their special needs and all the performance outcomes is essential.

One limitation of this study like other qualitative studies is an inability to generalize the findings of activity performance challenges in Iranian people with HF in the current study to other contexts and cultures. Another limitation is that the meaning units and codes could not be abstracted more than we did, because our purpose was to elaborate on activity performance with proper details.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The Ethical Code and standard of this article are based on the Declaration of Helsinki; also Ethical Committee of Iran University and Medical University approved the article (IR.IUMS.REC 1395.95-03-32-28606)

Funding

This study is extracted from the research entitled "The Problems in Daily occupation in the patient with heart failure NYHA 1-3" and was funded by Research Deputy of IUMS (Grant No.: 95-03-32-28606).

Authors' Contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, writing – original draft: Malahat Akbarfahimi and Zeinab Fathipour-Azar; Methodology, funding, and supervision: Malahat Akbarfahimi; Writing – review & editing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to appreciate Dr Abbas Ebadi for his methodological suggestions.

References

Full-Text: (1124 Views)

1. Introduction

Heart Failure (HF) is a condition in which the heart is unable to pump blood consistent with metabolic needs [1]. In Iran, the prevalence of chronic heart failure has been estimated at 3.337 in 10.000 [2]. Based on the available literature, the consequences of HF are cognitive problems, physical dysfunction, social isolation, and reduced endurance, that affect personal efficiency in activity performance, work, leisure, family roles, and Activities of Daily Living (ADL) [3, 4].

It is well known that the majority of people with HF encounter difficulties in ADL performance [5,6,7] and to optimize the satisfaction of adults with HF in all aspects of ADL performance, it is essential to have a deep understanding of their challenges. In the literature, very few problems have been mentioned. For example, Dunlay et al. using the Katz index for assessing ADL, confirmed the relationship between difficulty in ADL performance and mortality of people with HF. They introduced factors such as female sex, older age, diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, anemia, morbid obesity, and unmarried status as predictors of difficulty with ADLs [8]. Norberg et al. using the assessment of motor and process skills and the staircase of ADL for assessing the ADL ability, reported that their participants were independent in Personal Activities of Daily Living (PADL). However, at least 75% were dependent on one or more Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL), usually shopping [9]. By reviewing the literature, little information is found about the effects of HF symptoms, such as dyspnea, fatigue, weakness, etc. on daily activities. This deficit may be due to the special characteristics of ADL assessments.

There are several ADL assessments [10]. Mainly, there are two kinds of ADL assessments for people with HF, including general and specific. But based on evidence, general assessments such as Barthel index [11, 12], Klein-bell index [13], functional independent measurement [14], and PULSES profile [15] are too general and do not consider the effects of dyspnea, fatigue, weakness, swelling, and persistent cough on activities performance [10]. Furthermore, some specific tests such as Performance Measure for Activity of Daily Living-8 (PMADL-8) [16] and Daily Activity Questionnaire in Heart Failure (DAQIHF) [17] do not cover all areas of IADL and BADL as well as aforementioned parameters [10]. Since, based on the perspective of occupational performance in occupational therapy, the performance of clients is influenced by the interactions of person-task-environment, and the impression factors through evaluation and intervention are essential [18]. Some of the impression factors on a person’s performance are independence, safety, and adequacy (difficulty, pain, fatigue, dyspnea, societal standards, satisfaction, aberrant behaviors, and experience with the activity). Task demands based on task analysis include materials, tools, and equipment parameters. Moreover, the demands of the environments in which the task takes place are the physical, temporal or cultural characters of the context [19]. To conclude, there is a lack of available ADL assessments that clarify the influence of parameters such as dyspnea or fatigue on performing daily activities in HF.

Performing ADL is affected by lifestyle, context, and cultural characteristics [20] and to the best of our knowledge, there are no reports about the challenges of people with HF during ADL performance in an Iranian population. As a result, this study aims to identify the performance challenges and limitations while performing ADLs and the relationship between these challenges and HF symptoms.

2. Methods

Study design

This paper is a part of a more extensive study carried out through the exploratory sequential mixed method (qualitative-quantitative). In this stage, to explore the personal experiences of people with HF during performing their routine ADL, a qualitative content analysis was performed using continuous comparative analysis. Content analysis was used for the participant’s clarification of the content of the interview made through a systematic classification process of coding and identification of concepts or patterns [21, 22]. Data in the qualitative phase of the study were gathered by semi-structured in-depth interviews. The participants were selected by purposeful sampling method.

Study participants

In this study, 12 individuals with HF participated (Table 1).

Heart Failure (HF) is a condition in which the heart is unable to pump blood consistent with metabolic needs [1]. In Iran, the prevalence of chronic heart failure has been estimated at 3.337 in 10.000 [2]. Based on the available literature, the consequences of HF are cognitive problems, physical dysfunction, social isolation, and reduced endurance, that affect personal efficiency in activity performance, work, leisure, family roles, and Activities of Daily Living (ADL) [3, 4].

It is well known that the majority of people with HF encounter difficulties in ADL performance [5,6,7] and to optimize the satisfaction of adults with HF in all aspects of ADL performance, it is essential to have a deep understanding of their challenges. In the literature, very few problems have been mentioned. For example, Dunlay et al. using the Katz index for assessing ADL, confirmed the relationship between difficulty in ADL performance and mortality of people with HF. They introduced factors such as female sex, older age, diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, anemia, morbid obesity, and unmarried status as predictors of difficulty with ADLs [8]. Norberg et al. using the assessment of motor and process skills and the staircase of ADL for assessing the ADL ability, reported that their participants were independent in Personal Activities of Daily Living (PADL). However, at least 75% were dependent on one or more Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL), usually shopping [9]. By reviewing the literature, little information is found about the effects of HF symptoms, such as dyspnea, fatigue, weakness, etc. on daily activities. This deficit may be due to the special characteristics of ADL assessments.

There are several ADL assessments [10]. Mainly, there are two kinds of ADL assessments for people with HF, including general and specific. But based on evidence, general assessments such as Barthel index [11, 12], Klein-bell index [13], functional independent measurement [14], and PULSES profile [15] are too general and do not consider the effects of dyspnea, fatigue, weakness, swelling, and persistent cough on activities performance [10]. Furthermore, some specific tests such as Performance Measure for Activity of Daily Living-8 (PMADL-8) [16] and Daily Activity Questionnaire in Heart Failure (DAQIHF) [17] do not cover all areas of IADL and BADL as well as aforementioned parameters [10]. Since, based on the perspective of occupational performance in occupational therapy, the performance of clients is influenced by the interactions of person-task-environment, and the impression factors through evaluation and intervention are essential [18]. Some of the impression factors on a person’s performance are independence, safety, and adequacy (difficulty, pain, fatigue, dyspnea, societal standards, satisfaction, aberrant behaviors, and experience with the activity). Task demands based on task analysis include materials, tools, and equipment parameters. Moreover, the demands of the environments in which the task takes place are the physical, temporal or cultural characters of the context [19]. To conclude, there is a lack of available ADL assessments that clarify the influence of parameters such as dyspnea or fatigue on performing daily activities in HF.

Performing ADL is affected by lifestyle, context, and cultural characteristics [20] and to the best of our knowledge, there are no reports about the challenges of people with HF during ADL performance in an Iranian population. As a result, this study aims to identify the performance challenges and limitations while performing ADLs and the relationship between these challenges and HF symptoms.

2. Methods

Study design

This paper is a part of a more extensive study carried out through the exploratory sequential mixed method (qualitative-quantitative). In this stage, to explore the personal experiences of people with HF during performing their routine ADL, a qualitative content analysis was performed using continuous comparative analysis. Content analysis was used for the participant’s clarification of the content of the interview made through a systematic classification process of coding and identification of concepts or patterns [21, 22]. Data in the qualitative phase of the study were gathered by semi-structured in-depth interviews. The participants were selected by purposeful sampling method.

Study participants

In this study, 12 individuals with HF participated (Table 1).

The inclusion criteria consisted of having heart failure diagnosed by a cardiologist, having no neurological, psychiatric, or orthopedic diseases that affect heart function and ADL performance, MMSE (The Mini-Mental State Examination) score >21, being 36-65 years old and having Ejection Fraction (EF) >45% [23]. If any participant cannot provide the desired information, they were excluded from the study.

Data collection

The interviews were held in a quiet room in Rajai Hospital from June 2015 to December 2016 between 9 -12 AM. The selection of participants was with maximum diversity in culture, custom, age, level of education, and duration of heart failure to gather more extensive data. The first author recorded all interviews and transcribed verbatim. The beginning of all sessions accompanied by the designed guideline questions such as “What is your daily schedule?” “Are there any changes after your disease in the quality of your ADL performance?” “What are your limited activities?” and “ What factors have limited your activities?” The research team and expert panel created the interview guide. The expert panel consisted of four occupational therapists, two physical therapists, and one physician. The interviews ended with this question: Do you want to add more information? Finally, all participants were requested to review the transcript and confirm it. The interviews continued until data saturation. Sampling continued until no further information to extract.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using the Graneheim and Lundman method [22]. The first (F.Z) and fourth (A.B) authors were engaged in data analysis by reading the interviews several times line by line. Then the data were explored for meaning units. After abstracting the meaning units, codes, subcategories, and categories were extracted. At last, the underlying meanings were interpreted as themes. To achieve trustworthiness, the Lincoln and Guba approach was applied [24]. Through prolong engagement, the researcher spent enough time gathering data, and presenting the meaning units and initial codes to the research team for verification and feedback. Besides, investigator triangulation was utilized. One expert in qualitative research and one in occupational therapy checked data (expert check). Moreover, two colleagues who were involved in some other qualitative projects, commented on the emerged data as well (peer check). Finally, the transcriptions and codes were reviewed by the participants (member check).

Ethical approval

All participants signed informed consent before the interview and were aware of the aims of the project. The participants were permitted to withdraw from the study at any time and were guaranteed the confidentiality of their conversations. The ethical code of this study was approved by the Iran University of Medical Sciences (IR.IUMS.REC 1395.95-03-32- 28606).

3. Results

Twelve people with HF (4 females and 8 males) took part in this study. Each participant was interviewed to the point that data saturation was attained. The average interview time was 32.83 minutes ranging from 20 to 45 minutes. The demographic characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1.

The participants explained their challenges during performing ADL. Based on the data analysis, 2 themes and 4 categories were extracted. The themes consisted of “obstacles preventing normal functioning due to HF” and “disturbances in doing daily living activities as a burden due to HF”. The first theme consisted of 2 categories and 8 subcategories. The categories of the first theme include interference of previous experience in performance (4 subcategories) and challenges during the performance (4 subcategories). The second theme consisted of 2 categories and 13 subcategories. The categories of the second theme are entitled to personal laborious activities due to HF (7 subcategories) and interruption of activities performance related to family roles and outdoor tasks (6 subcategories) (Table 2).

Obstacles preventing normal functioning due to HF

Interference of previous experience in performance

During the interview, the participants mentioned that their bad experiences interfere with their current performance and it scares them from doing it again. For instance, they did not do some activities at all because they are difficult, they have not to value for them, or they are frightened because of a lack of safety during performance-based on physician prescription, previous experience, or so on. Some of their claims are as follow:

“I don’t iron because I’m not interested in doing it” (P-3).

“To feel safe I prefer not to do vacuuming but I can do it” (P-2).

“I don’t trip more because I fear to experience breath shortness” (P-9).

Doing some activities, which are important for participants should be done by others or give them up because of their problem due to HF.

“I need someone to help me in all activities” (P-8).

“I can’t do some of my tasks and my children should help me” (P-2).

The participants stated that performing some activities are difficult for them and they try to substitute it or give up it.

“It is difficult for me to go up the stairs” (P-4)

Challenges during the performance

The participants complained of the recurrence of symptoms of HF during ADL. They pointed to pain, dyspnea, prolongation of doing the activities, and the most frequently the fatigue.

Pain: “When I want to bend I feel a sharp pain in my chest” (P-4)

Dyspnea: “I can’t go up the stairs because of difficulty in breathing” (P-11).

“When it gets cold or warm I can’t breathe properly” (P-12).

Time duration: “If I want to go outside it takes me a long time to get ready” (P-10).

Fatigue: “I want to vacuum and do my home duties but I become exhausted after a short time” (P-10).

“I am exhausted and get out of the bathroom soon. My bathing lasts for 2 minutes because I fear to find myself in a dangerous situation I feel something bad happens”(P-12).

Disturbance in doing daily living activities as a burden due to HF

The results of this study revealed that daily living disturbances due to HF have two main categories. The participants suffer from doing several activities and complain of some interfering factors related to HF during doing their daily activities.

Personal laborious activities due to HF

Performing activities of daily living, which are essential for survival is a basic need for all human beings. However, the participants of the current study encounter difficulties in defecation, dressing, grooming, bathing, doing religious duties, health management, and sexual activities. For example, descriptions of 4 participants were as follows:

“Toileting is difficult for me because of sitting and I suffer from defecation problems” (P-4).

“Due to abdominal swelling, one must help me get dressed and tying shoelaces “(P-8).

“I can’t see some part of my body in terms of personal hygiene (body grooming) during bending due to abdominal swelling and pressure” (P-6).

“Bathing is challenging for me because I can’t stand and move so I need to sit down on a chair” (P-7).

“I say my prayer in a sitting position because I feel chest pain during bending” (P-4).

Sexual activities are a problem and maintaining the desired posture is frustrating.

“Overall, I have no marital relationship with my wife. From the day, I was ill because it is difficult for me to maintain the desire position. I have no sense in this regard so that I have the energy to do this activity” (P-11).

Interruption of activities performance related to family roles and outdoor tasks

The participants stated mobility limitation in the community for doing activities such as shopping, financial management in the bank, and so on due to lack of energy and walking or carrying. Depending on one’s level of performance, simple activities like sitting in different vehicles or average levels activities such as transferring to the car, walking, fast walking, and complicated activities such as going up and down the stairs are disrupted. These problems limited them to participate in the community for doing outdoor family roles. In this regard, 3 participants’ descriptions were as follows:

“I cannot lift heavy things and I suffer from shortness of breath. My walking is very limited. I would rather go by car. When climbing the stairs, my heart starts pounding and I have to take a rest for half an hour. Shopping is difficult for me to buy 5 kg of fruit and take them home as if my heart is collapsed when it becomes heavy” (P-7).

“ If I want to walk fast, chest pain is started, I cannot carry heavy things, I want to be like a normal person, I love to go hiking, but if I want to be in a rush, I can’t and must walk slowly “ (P-5).

“Going up and down the stairs is hard, I can’t walk long” (P-4).

Besides, using public transportation such as bus and subway is overwhelming because of sitting or standing for a long time and staying in a crowded space.

“I got on the subway train once, but I couldn’t stay any longer “(P-10).

Travelling is impossible for these individuals due to the need to sit for long hours.

“I used to go to the north for two or three days, but now I cannot do that. It is difficult for me now. I do not know what will happen in the way during traveling and I worried that if I get sick what will happen. For example, once I wanted to go to the north and I became sick along the way and the ambulance came...”. (P-9).

Driving with a personal car is a code with low frequency.

“I cannot drive. I cannot do that now” (P-1).

Devoting some time of day for the interests of the children and accompanying them are among the things that are lost in these individuals.

“I become reticent and isolated. I cannot communicate very much with my children; I do not have any energy” (P-11).

Housekeeping was an important activity for most participants and is particularly impaired in some cases. They stated the problems with cleaning activities like sweeping, tidying up the beds, doing laundry, washing the floor, and ironing, as well as kitchen-related activities such as washing the dishes, cutting, and chopping vegetables, meat, cooking, and so on.

“I used to vacuum clean, but now I can’t. I get short of breath and my heartbeat doesn’t allow me to do so” (P-3).

“Chopping is unbearable for me” (P-2).

4. Discussion

The results of the current study demonstrated some common challenges of people who suffer from heart failure during performing their daily living activities. The participants clarified the type of involved activities and the form of these challenges, which clarify some new perspective of the extent of influence of HF on their lives and maybe on their wellbeing. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no qualitative study on this issue and current questionnaires do not address these challenges for Iranian people with HF. As an occupational therapist with a top-down approach, investigating the problematic activities of daily living is essential. The participants of the current study complained about the distributing effect of HF on their ADLs. It is worth noting that our participants did not have any challenges with cognitive functions (MMSE > 21) and their NHYA (New York Heart Association Functional Classification) ranged between I to IV. Therefore, their major challenges were due to physical problems caused exclusively by HF, and the people who suffer from dementia or other cognitive disorders with the secondary complication of all heart disease were not included in the current study. Based on their perspective, 2 themes were extracted: obstacles preventing normal functioning due to HF, and disturbance in doing daily living activities as a burden due to HF.

Obstacles preventing normal functioning due to HF have 2 categories: interference of previous experience in performance and challenges during the performance. It can be realized that HF affects all aspects of the participant’s life. For example, the participants did not have any challenges with eating but they declared that the quality of performance of all daily activities has had changed.

In some cases, the participants preferred not to perform some daily activities based on unsuccessful experiences of performance in the past, such as falling, chest pain, and fatigue. They declared that after HF, some activities have lost their value for them. The most frequent devalued activities, in this case, were driving and caring for others. It seems that deprivation from doing something that was once valued and now should not be done due to the complication of HF causes people to become depressed and disappointed.

Difficulty and safety are recognized as interlinked performance parameters. Difficulty in doing activities was another complaint of participants that lead them to seek help or giving up activities. In the current study, the most frequent difficult activities to perform were housekeeping, bathing, and functional mobility. These findings in some way are consistent with Dunlay et al. study results which introduced eating, toileting, and dressing as the easiest activities and stair climbing, walking, and housekeeping as the hardest ones [8]. Norberg et al. introduced that bathing in PADL and transportation and shopping in IADL were the hardest activities to perform in their study population [9].

Challenges during the performance of activities is another category in the obstacles preventing normal functioning due to HF. The chief complaint of the participants during the performance of all activities of daily living was the manifestation of chest pain, the prolonged time duration of activity performance, early onset of fatigue, and dyspnea. According to the most frequent comments of the participants, the greatest confounder performing activities in HF was fatigue and dyspnea. This finding is consistent with other studies that show the relationship between fatigue, shortness of breath, and chest pain with physical activities in people with HF [9]. However, fatigue and cognitive impairments are the most common complaint in a variety of diseases such as multiple sclerosis and stroke [25,26,27], which usually the common intervention is assistive devices prescription and teaching energy conservation techniques [9]. Therefore, empowering people with HF with these educations and helping them to coach performance problems due to fatigue is essential.

Regarding the second theme extracted from the interviews, in two categories, two types of challenging activities were explored: having personal laborious activities due to HF and interruption of activities performance related to family roles and outdoor tasks. Although all ADLs were recognized as meaningful activities, frequently performed, and as the most important view, they are essential for survival, our participants declared that personal activities are much more challenging than family role-related and outside home activities. They justified it in two dimensions. In one sight, while personal activities such as defection and bathing have more private nature, seeking help from others is embarrassing. In the other view, the independent performance of personal activity is strongly linked to the ability to live independently at home alone. However, efficient implementation of family roles and outside home activities are much more related to well-being. Therefore, the effort to carry out personal activities independently is greater in their view.

In the current study, challenging personal activates were defecation, dressing, grooming, bathing, sexual activity, religious duties, and health management. However, the challenging family role-related and outside home activities were using public transportation, functional mobility, traveling, driving, child caring, and housekeeping. Since there is no other qualitative research in this regard, we compared the limited activities of the result of the current study with two existing questionnaires PMADL-8 and DAQIHF developed for assessing the functional outcome of all types of HF.

The development of PMADL-8 was based on the ICF model and the items extracted from the review of other ADL questionnaires. The original version consisted of 40 activities (13 BADLs and 27 IADLs); the number of items was reduced by experts. The final version consisted of 8 activities, in which the psychometric characteristics were confirmed by 130 people with HF in Japan. The items included 1- getting up and off from the floor without instruments, 2- washing your body and hair, 3- going up a flight of stairs without a handrail, 4- vacuuming your room, 5- pulling and closing a heavy sliding door, 6- getting into and out of a car, 7- walking at the same speed with someone of the same age, and 8- walking up a slight slope for 10 min [16]. Although these items are the same as some activities of the challenging activities in the current study, nearly all items seem to focus on mobility and two items were dedicated only to walking. However, important positions such as squatting and bending, which are more frequently used in activities such as dressing, bathing, and toileting in the Iranian lifestyle were ignored. Besides some activities such as praying, grooming, or caring for others had not been included.

DAQIHF is another questionnaire for HF patients. This questionnaire like PMADL-8 was designed by reviewing the acceptable questionnaires and consisted of 82 activities in 7 dimensions, including problems in sleep and resting periods, washing, meals, toilet, household, and related activities, sport and non-sport leisure time activities [17]. These activities are not limited to ADL and other occupational domains were included and mainly were based on physical activity, so and they did not consider other aspects of performance outcomes of ADLs such as pain, safety, and so on.

The evidence in the present study confirms that the challenging activities in our participants are much broader than those mentioned in these two specialized questionnaires. For instance, spiritual issues and the need to do religious activities were noteworthy for many people suffering from debilitation diseases [28] and frequently mentioned by present participants but in these two special questionnaires for people with HF as a chronic disease, these activities were not included. Also, they announced that despite the need to have sex with their spouse they suppress themselves because of the HF problems.

5. Conclusion

HF is a chronic disease in which people with this problem should live with a wide spectrum of limitations in daily activities and tolerate some distributing factors that interfere with their performance. Therefore, exploring their needs and limitations for proper interventions to keep up their ability to perform ADL and live independently is essential. Previous studies confirm their limitations and two available assessments exist to evaluate the occupations of HF. However, some diversity of lifestyle and the effect of culture on ADL performance made us design this qualitative research for better understanding the special needs of people with HF in Iran. According to the findings of this study, people with HF experienced challenges during the performance of all areas of ADL related to themselves or their family roles and outside home duties. Their experiences of insecurity, dependency, and having difficulty strongly influenced their performances in new tasks or different situations. The performance outcomes such as pain, dyspnea, fatigue, and prolonged-time duration were the main confounder of performance in HF. Having a convenient assessment of ADLs for special disorders is fundamental [29]. It seems that developing a questionnaire for assessing ADL in people with HF with considering their special needs and all the performance outcomes is essential.

One limitation of this study like other qualitative studies is an inability to generalize the findings of activity performance challenges in Iranian people with HF in the current study to other contexts and cultures. Another limitation is that the meaning units and codes could not be abstracted more than we did, because our purpose was to elaborate on activity performance with proper details.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The Ethical Code and standard of this article are based on the Declaration of Helsinki; also Ethical Committee of Iran University and Medical University approved the article (IR.IUMS.REC 1395.95-03-32-28606)

Funding

This study is extracted from the research entitled "The Problems in Daily occupation in the patient with heart failure NYHA 1-3" and was funded by Research Deputy of IUMS (Grant No.: 95-03-32-28606).

Authors' Contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, writing – original draft: Malahat Akbarfahimi and Zeinab Fathipour-Azar; Methodology, funding, and supervision: Malahat Akbarfahimi; Writing – review & editing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to appreciate Dr Abbas Ebadi for his methodological suggestions.

References

- Dassanayaka S, Jones SP. Recent developments in heart failure. Circulation Research. 2015; 117(7):e58-63. [DOI:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.305765] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Naderi N, Bakhshandeh H, Amin A, Taghavi S, Dadashi M, Maleki M. Development and validation of the first iranian questionnaire to assess quality of life in patients with heart failure: IHF-QoL. Research in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2012; 1(1):10-6. [DOI:10.5812/cardiovascmed.4186] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Celano CM, Villegas AC, Albanese AM, Gaggin HK, Huffman JC. Depression and anxiety in heart failure: A review. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2018; 26(4):175-84. [DOI:10.1097/HRP.0000000000000162] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Lapier TK. Utility of the late life function and disability instrument as an outcome measure in patients participating in outpatient cardiac rehabilitation: A preliminary study. Physiotherapy Canada. 2012; 64(1):53-62. [DOI:10.3138/ptc.2010-30] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Yamashita M, Kamiya K, Hamazaki N, Matsuzawa R, Nozaki K, Ichikawa T, et al. Prognostic value of instrumental activity of daily living in initial heart failure hospitalization patients aged 65 years or older. Heart and Vessels. 2020; 35(3):360-6. [DOI:10.1007/s00380-019-01490-2] [PMID]

- Tinetti ME, McAvay G, Chang SS, Ning Y, Newman AB, Fitzpatrick A, et al. Effect of chronic disease-related symptoms and impairments on universal health outcomes in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2011; 59(9):1618-27. [DOI:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03576.x] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Tinetti ME, McAvay GJ, Chang SS, Newman AB, Fitzpatrick AL, Fried TR, et al. Contribution of multiple chronic conditions to universal health outcomes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2011; 59(9):1686-91. [DOI:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03573.x] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Dunlay SM, Manemann SM, Chamberlain AM, Cheville AL, Jiang R, Weston SA, et al. Activities of daily living and outcomes in heart failure. Circulation Heart Failure. 2015; 8(2):261-7. [DOI:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001542] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Norberg EB, Boman K, Lofgren B. Activities of daily living for old persons in primary health care with chronic heart failure. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2008; 22(2):203-10. [DOI:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00514.x] [PMID]

- Fathipour-Azar Z, Akbarfahimi M, Vasaghi-Gharamaleki B, Naderi N. Evaluation of activities of daily living instruments in cardiac patients: Narrative review. Journal of Modern Rehabilitation. 2016; 10(3):139-43. https://jmr.tums.ac.ir/index.php/jmr/article/view/43

- Collin C, Wade DT, Davies S, Horne V. The Barthel ADL Index: A reliability study. International Disability Studies. 1988; 10(2):61-3. [DOI:10.3109/09638288809164103] [PMID]

- Wade DT, Collin C. The Barthel ADL Index: A standard measure of physical disability? International Disability Studies. 1988; 10(2):64-7. [DOI:10.3109/09638288809164105] [PMID]

- Klein RM, Bell B. Self-care skills: Behavioral measurement with Klein-Bell ADL scale. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1982; 63(7):335-8. [PMID]

- Keith RA, Granger CV, Hamilton BB, Sherwin FS. The functional independence measure: A new tool for rehabilitation. Advances in Clinical Rehabilitation. 1987; 1:6-18. [PMID]

- Moskowitz E. PULSES profile in retrospect. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1985; 66(9):647-8. [PMID]

- Shimizu Y, Yamada S, Suzuki M, Miyoshi H, Kono Y, Izawa H, et al. Development of the performance measure for activities of daily living-8 for patients with congestive heart failure: A preliminary study. Gerontology. 2010; 56(5):459-66. [DOI:10.1159/000248628] [PMID]

- Garet M, Degache F, Costes F, Da-Costa A, Lacour JR, Barthelemy JC, et al. DAQIHF: methodology and validation of a daily activity questionnaire in heart failure. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2004; 36(8):1275-82. [DOI:10.1249/01.MSS.0000135776.09613.0D] [PMID]

- Meyer A. The philosophy of occupation therapy. Archives of Occupational Therapy. 1922; 1(1):1-10. https://journals.lww.com/ajpmr/Citation/1922/02000/THE_PHILOSOPHY_OF_OCCUPATION_THERAPY_.1.aspx

- Willard HS, Spackman CS. Willard and spackman’s occupational therapy. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

- Paul S. Culture and its influence on occupational therapy evaluation. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1995; 62(3):154-61. [DOI:10.1177/000841749506200307] [PMID]

- Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal Of Advanced Nursing. 2008; 62(1):107-15. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x] [PMID]

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004; 24(2):105-12. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001] [PMID]

- Green CP, Porter CB, Bresnahan DR, Spertus JA. Development and evaluation of the Kansas City cardiomyopathy questionnaire: A new health status measure for heart failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2000; 35(5):1245-55. [DOI:10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00531-3]

- Guba EG. Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. Educational Communication and Technology 1981; 29(2):75-91. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02766777

- Paciaroni M, Acciarresi M. Poststroke fatigue. Stroke. 2019; 50(7):1927-33. [DOI:10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.023552] [PMID]

- Heidari M, Akbarfahimi M, Salehi M, Nabavi SM. [Validity and reliability of the Persian-version of fatigue impact scale in multiple sclerosis patients in Iran (Persian)]. Koomesh. 2014; 15(3):295-301. http://koomeshjournal.semums.ac.ir/article-1-1951-en.html

- Akbari S, Lyden PD, Kamali M, Akbarfahimi M. [Correlations among impairment, daily activities and thinking operations after stroke (Persian)]. NeuroRehabilitation. 2013; 33(1):153–60. [DOI: 10.3233/NRE-130940]

- Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Worth A, Benton TF. Exploring the spiritual needs of people dying of lung cancer or heart failure: A prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers. Palliative Medicine. 2004; 18(1):39-45. [DOI:10.1191/0269216304pm837oa] [PMID]

- Roley S, DeLany JV, Barrows C, Honaker D, Sava D, Talley V. Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process. The American Occupational Therapy Association. 2008; 62(6):625-83. https://www.just.edu.jo/Documents/OT203%20-%20syllabus.pdf

Article type: Original Research Articles |

Subject:

Occupational therapy

Received: 2019/09/23 | Accepted: 2020/01/20 | Published: 2020/09/1

Received: 2019/09/23 | Accepted: 2020/01/20 | Published: 2020/09/1

Send email to the article author