Volume 19, Issue 1 (March 2021)

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2021, 19(1): 1-12 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Dadkhah S, Jarareh J, Akbari Asbagh F. The Relationships Between Self-compassion, Positive and Negative Affect, and Marital Quality in Infertile Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2021; 19 (1) :1-12

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1221-en.html

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1221-en.html

1- Department of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Faculty of Counseling, North Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Faculty of Counseling, Shahid Rajaee University, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Tehran University of Medical Sciences and Health Services, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Faculty of Counseling, Shahid Rajaee University, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Tehran University of Medical Sciences and Health Services, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 702 kb]

(2291 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (6378 Views)

Full-Text: (1850 Views)

1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), infertility is a reproductive system condition, i.e., defined as an inability to become pregnant after ≥1 year of attempting to conceive with regular intercourse without any protection [1]. Infertility and its treatment are challenging for infertile couples. Thus, it may cause numerous biopsychological problems, especially in infertile women. Failure in infertility treatment procedures, along with the problems caused by infertility, can lead to or intensify various biopsychological complications in infertile women [2].

The occurrence of psychological complications in infertile couples is estimated to be 25%-60% globally. Accordingly, it is caused by such complications as the origin and duration of infertility, gender, treatment techniques, and culture [3].

Infertility treatment in infertile women may be associated with decreased quality of marital life. Accordingly, such conditions may lead to serious marital problems and unsuccessful infertility treatment. Other psychological factors considered in this review that may influence infertile women’s lives are positive and negative affect and self-compassion [4].

The most recent systematic review on psychological factors affecting infertile women’s life was performed in 2015; it was reviewed in section 3.5. of the present systematic review. The current study aimed to review the relationship between self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality in infertile women, which can affect the success rate of the infertility treatment process in infertile women. Subsequently, receiving any psychological rehabilitation support while struggling with infertility could significantly alter their marital life [5].

2. Methods

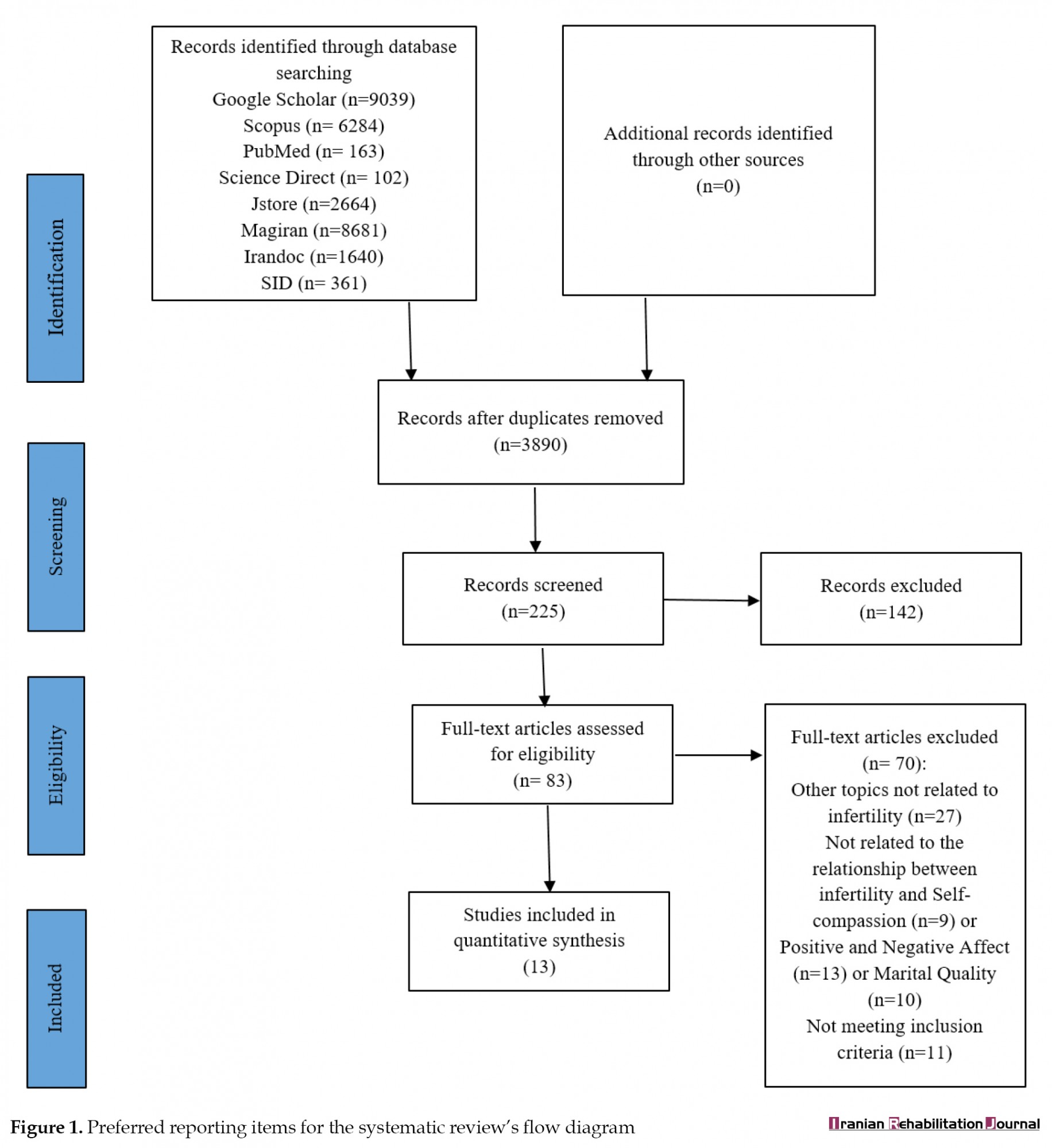

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) guidelines were used as the literature search protocol in this systematic review [6].

Investigations with the following characteristics were eligible to enter the study: being published in English and Persian; having a quantitative study design; study samples to include infertile women/couples, and employing a valid and reliable measure of well-known psychological factors, i.e., related to self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality. Quantitative studies were only included and the following articles were excluded: studies on fertile women/couples or any other population other than infertile women/couples, and using a qualitative design.

The searched databases included Pubmed, Google Scholar, Scopus, Science Direct, Jstore, The Cochrane Library, Medline, SID, Irandoc, Civilica, and Magiran.

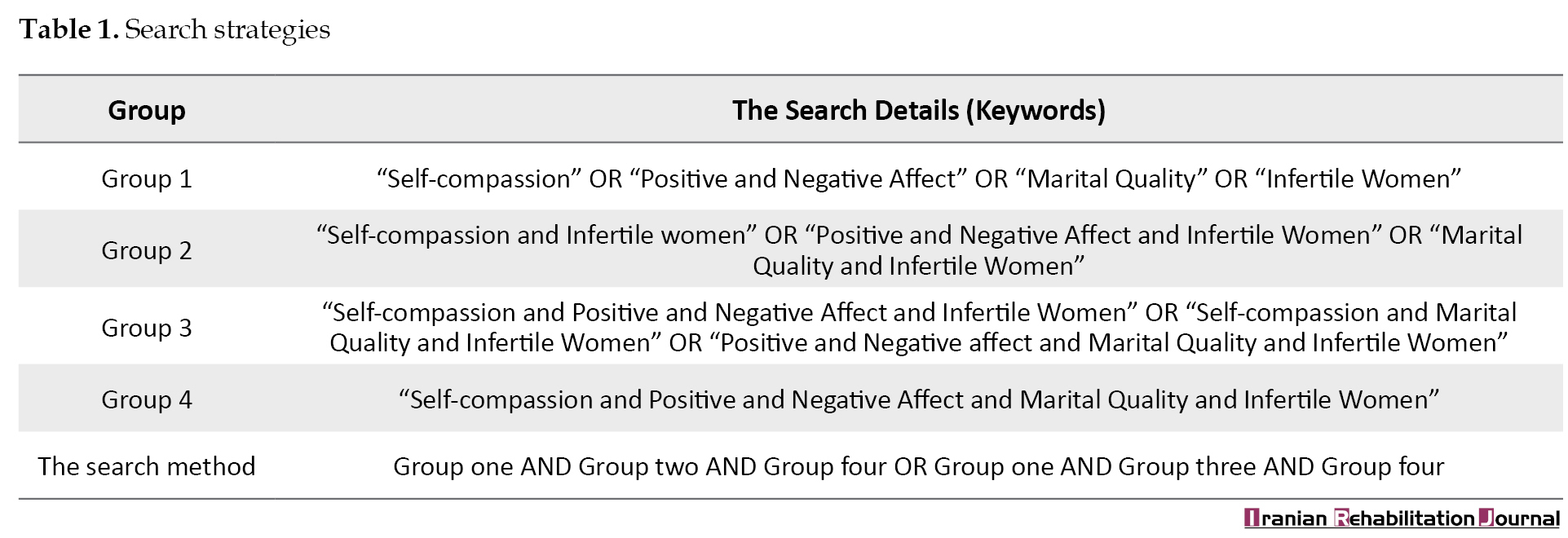

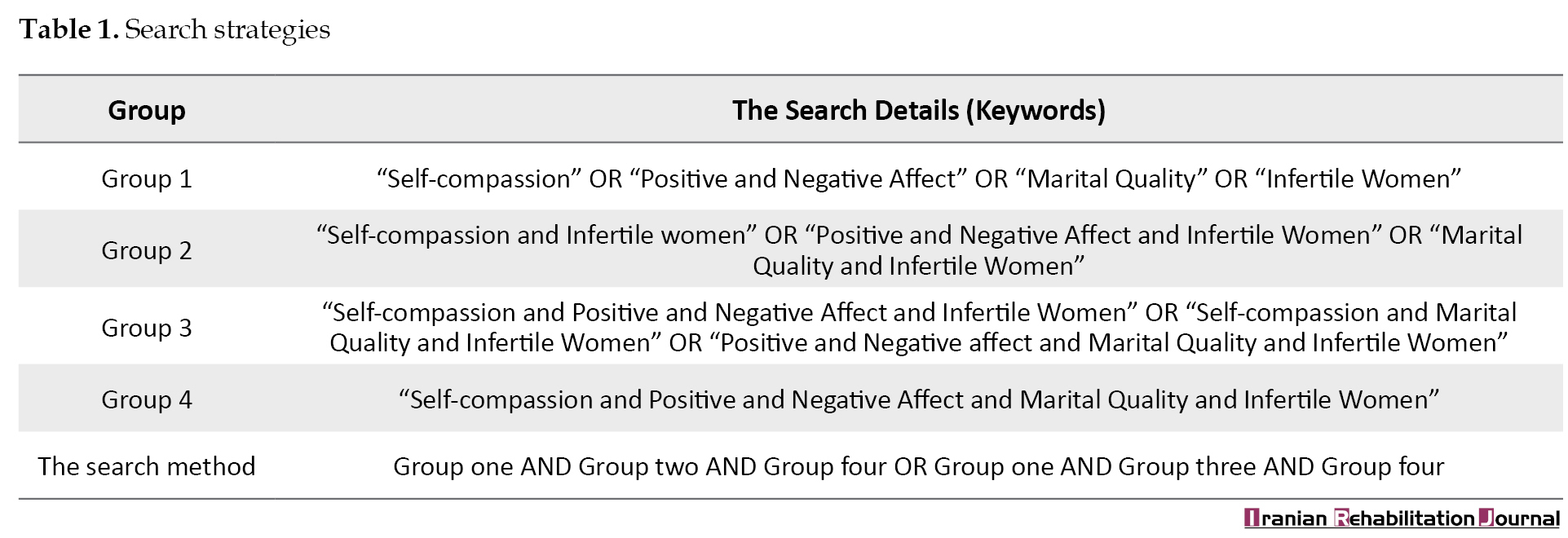

A comprehensive search was performed using the subsequent keywords and Boolean operators, as follows: “self-compassion (subject term) AND infertility, positive and negative affect (subject term) AND infertility, marital quality (subject term) AND infertility”. The initial search provided 367 articles. The search scope was then limited to English and Persian articles (n=225). Moreover, there were no recently published systematic reviews in the Cochrane databases. Table 1 illustrates the search strategies of the selected articles (Table 1).

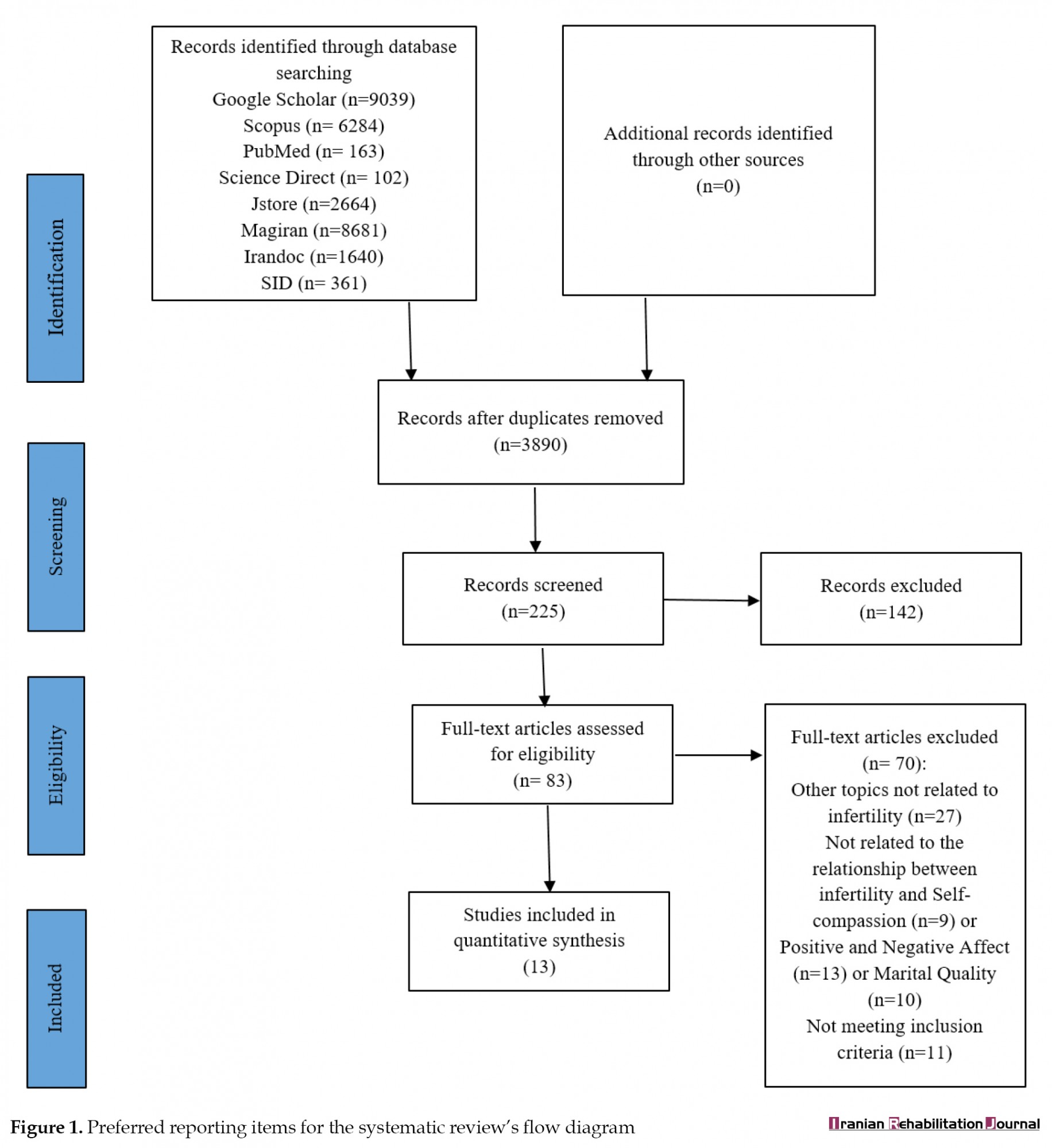

Having screened the studies for suitability by reading their titles, abstracts, and results, 13 published papers were recognized as eligible. Figure 1 demonstrates the assortment for the inclusion procedure.

In total, 13 published studies were included in this systematic review; they were evaluated by each of the co-authors to develop a synthesis of the significant findings concerning the relationship between self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality in infertile women. The screened manuscripts were carefully read for similarities or discrepancies in applying intangible or theoretical outlines that guided the studies, and the techniques used to find the relationship between self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality in infertile women.

3. Results

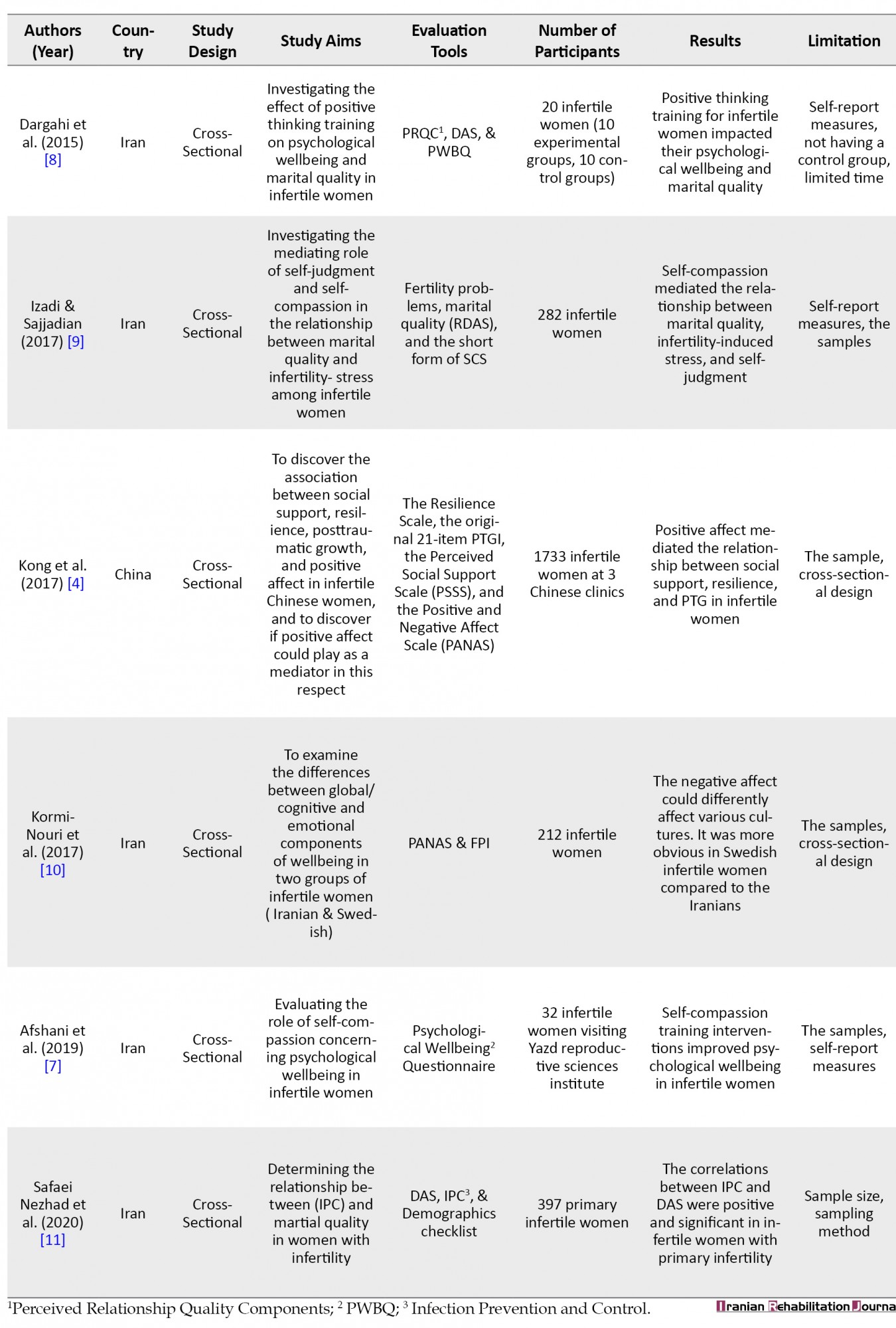

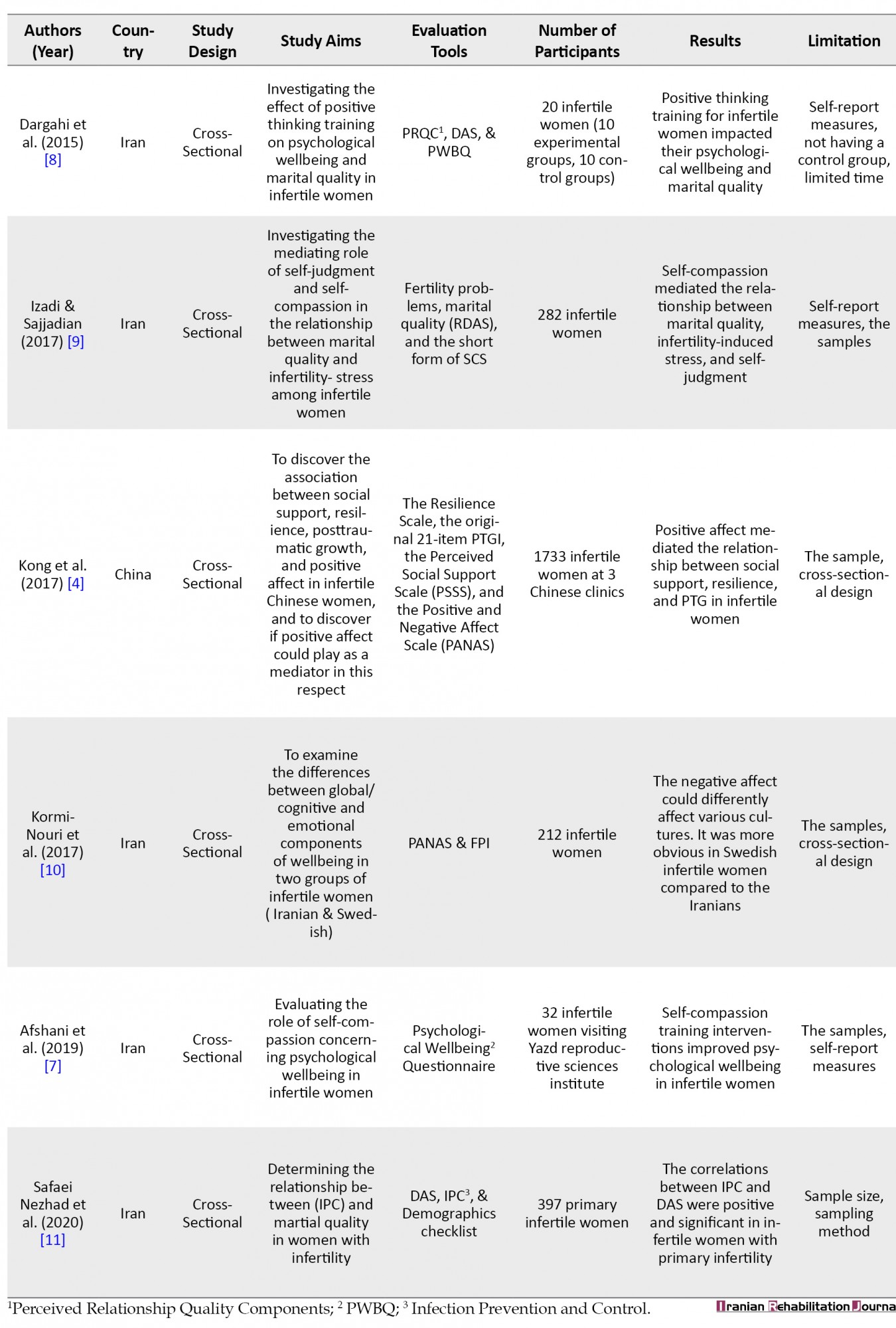

Thirteen published articles were included in this research; all the articles were quantitative and published between 2000 and 2020. The included articles revealed a global standpoint on the relationship between self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality in infertile women, including Iran [7, 8, 9, 10, 11] USA [5, 12, 13, 14, 15], Portugal [16], China [4, 17], and South Africa [18]. Most of the included studies used a cross-sectional research design. Table 2 presents a summary of the included studies, containing authors, the location of study, the year of publication, study design, the study purposes, sample size, measurement instruments, and results.

Evaluating the studies to detect the measurement tools used to operationalize self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality revealed cohesion between the involved studies. A common instrument used to measure self-compassion was the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS), i.e., a 26-item measure of self-compassion. Internal reliability for all 26 items is reported to be >0.70 (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient=0.81-0.83) [19]. A common instrument used to measure positive and negative affect was the Positive Affect and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS). The PANAS is a 20-item measure of positive and negative affect. Internal reliability for all 26 items is reported to be >0.84 (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient=0.84-0.90) [20]. The commonly-used marital quality measure was the Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale (RDAS). The RDAS is a 14-item measure of marital quality. Internal reliability for all 26 items is measured as >0.79 (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient=0.79-0.90) [21].

Data were collected from 13 primary studies to investigate the relationships between self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality in infertile women. Differences were identified between those studies which used infertility as a single variable, compared to other studies that used infertility as the main problem and evaluate other psychological factors, like self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality in infertile women. Moreover, differences were identified between those studies which used problem-focused coping style. Significantly, there was a sizable effect size between studies; these data provided that self-compassion could play a mediating role in the relationship between positive and negative affect and marital quality in infertile women. There were no studies on the direct or indirect relationship between self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality in infertile women. Five of the examined studies focused on the relationship between infertility and self-compassion [5, 7, 9, 14, 16]. Four of the included studies focused on the relationship between infertility and positive and negative affect [4, 5, 10, 14]. Seven of the reviewed studies concentrated on the relationship between infertility and marital quality [8, 9, 11, 12, 16, 17, 18]; two studies concentrated on the relationship between infertility, self-compassion, and marital quality [9, 16]; and, one study focused on the interactions between infertility and coping style [5].

There was no association between self-compassion and marital quality. It was concluded that self-compassion could play a mediating role in the diagnosis of infertility and can lead to improved mental health status. Furthermore, coping techniques directed at addressing negative effects and stressors generally were connected with infertility; the infertility treatment process could have the potential to progress mental health and social and marital relationship in infertile women [5].

The quality of studies was graded by the GRADE from the Cochrane handbook [22]. Except for two of the studies which had low quality, the rest included medium- and high-quality primary studies. The studies were tested concerning design, risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication.

The most recent systematic review on the relationship between psychological factors in infertile women was performed in 2015 and included 172 infertile women (primary & secondary) [5]. The latest review concluded that both groups of infertile women reported similar levels of self-compassion, global fertility-related stress, and subjective wellbeing. It was also revealed that self-compassion plays as a mediator in the relationship between wellbeing and parenting needs in infertile women. Furthermore, self-compassion mediated the relationship between social anxiety and wellbeing among infertile females [5].

Infertility and the subsequent problems are associated with not having a child as well as issues, such as family and marital turmoil; the feeling of rejection from others; blaming oneself and others, and various personality, psychological, family, and communication function impairments. The financial burden of biopsychological rehabilitation, required for infertile groups is increasing worldwide. Some infertility-induced problems could be the excessive costs of infertility treatment; constant worrying about the effectiveness of the treatment and the process; the fear of family breakdown, and the loss of interest in the spouse. According to some studies, the marital quality of infertile women decreases; in some cases, it leads to divorce while the couple is struggling with infertility problems [23].

Infertility exposes couples to sexual and marital problems, reduced intimacy, guilt, depression, and feelings of emptiness. Besides, these psychological and emotional complications could be considered among the causes of infertility [24]. Marital quality is considered among the major aspects of infertile women’s life; it plays an essential role in evaluating and predicting family communication’s overall quality [15]. Moreover, marital quality has a multidimensional concept. It includes various aspects of a couple’s communication, such as satisfaction, adjustment, cohesion, happiness, and commitment [25].

Studies suggested that infertile couples are less likely to cope with their problems than fertile couples are. This is mostly because they anticipate negative outcomes. As this pattern continues, important issues, such as solving everyday life problems, family finances, and even emotional issues, such as expressing love, emotional intimacy, and unresolved sexual intimacy remain unresolved. Researchers believe that infertile couple’s marital satisfaction and marital quality are significantly lower, compared to fertile couple’s marital satisfaction level, which could be associated with their sociodemographic and healing experience [9, 11].

Self-compassion requires being kind and understanding toward self when one suffers, fails, or feels inadequate, rather than disregarding pain or self-punishment and self-criticism. Moreover, it indicates being patient and kind to others and having a non-judgmental understanding of them. This idea reflects that one’s life experiences and problems are part of the issues that others are experiencing. Self-compassion is associated with feelings of self-love and concern for others; however, it does not covey self-centeredness or preference for one’s needs [25]. Studies revealed that women who are less likely to self-blame for failure and are more forgiving of perceived shortcomings enjoy a better mental health status [8]. Self-compassion mediates the association between social anxiety and psychological wellbeing in infertile women. This is because of the social problems, including social identity and isolation which infertile women experience while encountering infertility [5].

Emotion is one of the most critical elements of behavior. Emotional experiences can boost energy and strength concerning one’s behavior. Furthermore, emotion is the most crucial regulator of psychosocial, occupational, and educational functions. Every emotional experience is also of an emotional aspect. Some studies demonstrated that emotional experience has positive and negative dimensions [4, 14, 26]. These characteristics represent different dimensions of emotion [27]. The high rates of discontinuing infertility treatment are implicated by psychological complications in coping with the emotional necessities of this intervention [28]. Positive affect reflects one’s passion for life and determines how active and alert they feel. High levels of positive affect designate greater levels of energy, complete focus, and enjoyable employment; however, low levels of positive affect indicate sadness and exhaustion. Negative affect is a general dimension of inner distress and unpleasant employment. Besides, it conveys unpleasant moods, such as irritation, hatred, blame, fear, and anxiety; however, low levels of negative affect are associated with relaxation and comfort [10]. Positive affect and negative affect can concurrently co-occur, representing that they do not exist at the opposite ends of a scale [26].

The co-authors characterized the combination of experiential indication from the included articles into 4 groups; self-compassion, positive and negative affect, marital quality, and infertile women. These groups were considered after the analysis and in-depth argument of cohesions and dissimilarities in study findings.

4. Discussion

The present review study investigated self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality in infertile women. We also attempted to find a better understanding of psychological factors affecting infertile women’s mental health; accordingly, different promoting behaviors were explored to help them cope with challenging and stressful infertility treatment. A review of studies has highlighted that infertile couples, especially infertile women, are more prone to using avoidance mechanisms, experimental avoidance, and coping styles with the least emotion and distance to cope with the problems when undergoing infertility treatment. Additionally, the odds of using avoidant coping strategies are higher in infertile couples, compared to their fertile counterparts [16].

Researchers have documented that marital quality can adversely and significantly predict negative affect in women. The stronger the marital quality, the greater the commitment and emotional exchange between the couples; the more the women’s emotional needs; and the higher their negative affect decreases. Negative affect seems to divert attention to internal worries and prevent emotional exchange between couples; thus, increasing the level of marital quality and women’s life satisfaction as well as reducing their negative affect [29]. Although marital quality is complicated in infertile couples, some studies have indicated a strong marital quality in infertile couples. According to studies, the stages of diagnosis and treatment of infertility facilitate communication and intimacy between couples; thus, they will feel more intimate with each other [5]. Moreover, other aspects, such as the age of infertile couples, sexual satisfaction, the coordination of couples’ perception of infertility, and their educational level are related to marital quality [12, 14]. Infertility counseling with infertile couples concerning the sexual response cycle and sexual health can improve sexual satisfaction and marital quality among infertile females [20]. Scholars also found that teaching life quality skills significantly improve marital quality among infertile women [30].

A review of some studies indicated that fertile women experience a higher positive affect, compared to infertile females. Moreover, there was a significant difference in positive and negative affect between fertile and infertile women. Studies demonstrated that self-compassion mediates positive and negative affect by affecting infertility stress and reduces stress levels in infertile women. Infertile women experience negative affect, e.g. anger, frustration, and fear due to stress-induced infertility. Accordingly, self-compassion can help infertile women with reducing negative affect and preparing the right environment for positive affect, e.g. happiness and interest. Infertile women with high levels of self-compassion experience greater positive affect and less negative affect. Moreover, lower levels of self-compassion in infertile women indicate a higher extent of negative affect [5].

Women with positive affect are usually enthusiastic, energetic, confident, active, and alert. Positive affect positively impacts one’s interaction with others and surroundings. Positive affect is an integral part of everyday life. Furthermore, such emotions help individuals process emotional data to solve problems, make the right planning, and accurately and efficiently achieve success [4]. Researchers consider self-compassion as a fundamental construct in emotion regulation and balance; they investigated if it is a function of adaptive strategies for organizing emotions by reducing negative affect and creating positive affect, e.g. kindness and social cohesion [25]. According to studies, self-compassion significantly affects the relationship between positive and negative affect and hope in infertile women [14]. There was a positive and significant relationship between psychological health, self-compassion, and marital quality in couples. Infertile couple’s self-compassion can explain the changes in their marital adjustment [9]. Gallardo [30]indicated that self-compassion plays a mediating role between inner shame and stress induced by infertility. Besides, it can mediate the effect of marital quality on infertility-induced stress [9]. Another study found that self-compassion played an essential mediating role in social anxiety and mental health among infertile women. This is due to their complex social identities and social isolation. Infertility can also help infertile women as an emotion regulation strategy; it is also a characteristic in accelerating repression, self-blame, or other-blame [31].

Infertility stress, especially in women, can be a combination of internal self-compassion and the lack of support for others; thus, self-compassion, as an internal factor, can develop emotion through self-awareness rather than judging or criticizing one’s shortcomings and inadequacies [14]. Mantelou and Karakasidou [29] examined the relationship between self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and life satisfaction. Subsequently, they found that promoting self-compassion enhances increases the level of positive affect; as a result, self-compassionate individuals experience a high extent of positive affect. Individuals with high levels of self-compassion resolve interpersonal conflicts by considering the needs of self and others. Infertile women can improve their communication with others through self-compassion; consequently, they will gain further support from others. Thus, the odds of assessing the problems of infertility as stressful decreases. Eventually, such measures help them to promote their level of self-compassion and reduce the stress of the infertility treatment process [25].

Self-compassion-based treatment and self-judgment reduction could be implemented to reduce infertility-induced stress and improve compatibility and marital quality in infertile couples [5]. These findings highlight the significance of paying attention to positive psychological variables when working with infertile women; research indicated that increasing interpersonal skills improve marital quality [29].

There is a conspicuous absence in the literature when trying to comprehend the relationship between self-compassion and marital quality in infertile women as well as the association between self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality altogether. For instance, studies distinguishing the direct or indirect relationship between self-compassion and marital quality in infertile women are scarce. Moreover, there is inadequate data about the age group of infertile women in most of the studies which can limit the investigations. This is mostly because the age group that goes through infertility treatment matters, especially due to a golden period for achieving a successful result. Future studies need to address the direct or indirect relationship between self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality in infertile women. Additionally, there is a necessity to investigate the age group, education, and source of infertility in infertile women to reach accurate results.

The findings of this systematic review indicated a large gap in the development of the complication of the design of studies, i.e., ambiguous. To continue to shape evidence concerning the relationship between self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality in infertile women, studies must reflect the direct or indirect relationship between specific variables. Such characteristics include self-compassion and positive and negative affect and marital quality (3 variables) to understand the precise intervention design and testing.

This systematic review was directed with precision and devotion to the PRISMA guidelines. Constructed on careful evaluations of the studies included in this review, the results of the synthesis are rationally presented. The included studies also provided a general picture of the universal difficulties of coping with infertility in women/couples to the readers. Moreover, being geographically dispersed could be counted as a strength of this systematic review.

The obtained data were restricted to rational implications from included studies. It was also recognized that not all studies were planned to contain the identified elements, i.e., significant to marital quality in infertile women. The wide-ranging geographic basis of the study also limited concluding any particular healthcare system or culture.

5. Conclusion

Based on this systematic review, some studies assumed that self-compassion could play a mediating role between positive and negative affect and marital quality among infertile women. The present gaps in the literature are linked to interventions, age, culture, and the duration of experiencing infertility. Besides, there is insufficient research based on the relationship between more than two psychological variables.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University Science and Research Branch (Code: IR.IAU.SRB.REC.1398.021).

Funding

The authors received no financial support for this study.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and Supervision: Sepideh Dadkhah, Jamshid Jarareh, Firoozeh Akbari Asbagh; Methodology: Sepideh Dadkhah; Investigation, Writing – original draft, and Writing – review & editing: All authors; Data collection and Data analysis: Sepideh Dadkhah

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all scholars helped us in data collection and writing this systematic and meta-analysis review.

References

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), infertility is a reproductive system condition, i.e., defined as an inability to become pregnant after ≥1 year of attempting to conceive with regular intercourse without any protection [1]. Infertility and its treatment are challenging for infertile couples. Thus, it may cause numerous biopsychological problems, especially in infertile women. Failure in infertility treatment procedures, along with the problems caused by infertility, can lead to or intensify various biopsychological complications in infertile women [2].

The occurrence of psychological complications in infertile couples is estimated to be 25%-60% globally. Accordingly, it is caused by such complications as the origin and duration of infertility, gender, treatment techniques, and culture [3].

Infertility treatment in infertile women may be associated with decreased quality of marital life. Accordingly, such conditions may lead to serious marital problems and unsuccessful infertility treatment. Other psychological factors considered in this review that may influence infertile women’s lives are positive and negative affect and self-compassion [4].

The most recent systematic review on psychological factors affecting infertile women’s life was performed in 2015; it was reviewed in section 3.5. of the present systematic review. The current study aimed to review the relationship between self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality in infertile women, which can affect the success rate of the infertility treatment process in infertile women. Subsequently, receiving any psychological rehabilitation support while struggling with infertility could significantly alter their marital life [5].

2. Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) guidelines were used as the literature search protocol in this systematic review [6].

Investigations with the following characteristics were eligible to enter the study: being published in English and Persian; having a quantitative study design; study samples to include infertile women/couples, and employing a valid and reliable measure of well-known psychological factors, i.e., related to self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality. Quantitative studies were only included and the following articles were excluded: studies on fertile women/couples or any other population other than infertile women/couples, and using a qualitative design.

The searched databases included Pubmed, Google Scholar, Scopus, Science Direct, Jstore, The Cochrane Library, Medline, SID, Irandoc, Civilica, and Magiran.

A comprehensive search was performed using the subsequent keywords and Boolean operators, as follows: “self-compassion (subject term) AND infertility, positive and negative affect (subject term) AND infertility, marital quality (subject term) AND infertility”. The initial search provided 367 articles. The search scope was then limited to English and Persian articles (n=225). Moreover, there were no recently published systematic reviews in the Cochrane databases. Table 1 illustrates the search strategies of the selected articles (Table 1).

Having screened the studies for suitability by reading their titles, abstracts, and results, 13 published papers were recognized as eligible. Figure 1 demonstrates the assortment for the inclusion procedure.

In total, 13 published studies were included in this systematic review; they were evaluated by each of the co-authors to develop a synthesis of the significant findings concerning the relationship between self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality in infertile women. The screened manuscripts were carefully read for similarities or discrepancies in applying intangible or theoretical outlines that guided the studies, and the techniques used to find the relationship between self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality in infertile women.

3. Results

Thirteen published articles were included in this research; all the articles were quantitative and published between 2000 and 2020. The included articles revealed a global standpoint on the relationship between self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality in infertile women, including Iran [7, 8, 9, 10, 11] USA [5, 12, 13, 14, 15], Portugal [16], China [4, 17], and South Africa [18]. Most of the included studies used a cross-sectional research design. Table 2 presents a summary of the included studies, containing authors, the location of study, the year of publication, study design, the study purposes, sample size, measurement instruments, and results.

Evaluating the studies to detect the measurement tools used to operationalize self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality revealed cohesion between the involved studies. A common instrument used to measure self-compassion was the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS), i.e., a 26-item measure of self-compassion. Internal reliability for all 26 items is reported to be >0.70 (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient=0.81-0.83) [19]. A common instrument used to measure positive and negative affect was the Positive Affect and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS). The PANAS is a 20-item measure of positive and negative affect. Internal reliability for all 26 items is reported to be >0.84 (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient=0.84-0.90) [20]. The commonly-used marital quality measure was the Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale (RDAS). The RDAS is a 14-item measure of marital quality. Internal reliability for all 26 items is measured as >0.79 (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient=0.79-0.90) [21].

Data were collected from 13 primary studies to investigate the relationships between self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality in infertile women. Differences were identified between those studies which used infertility as a single variable, compared to other studies that used infertility as the main problem and evaluate other psychological factors, like self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality in infertile women. Moreover, differences were identified between those studies which used problem-focused coping style. Significantly, there was a sizable effect size between studies; these data provided that self-compassion could play a mediating role in the relationship between positive and negative affect and marital quality in infertile women. There were no studies on the direct or indirect relationship between self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality in infertile women. Five of the examined studies focused on the relationship between infertility and self-compassion [5, 7, 9, 14, 16]. Four of the included studies focused on the relationship between infertility and positive and negative affect [4, 5, 10, 14]. Seven of the reviewed studies concentrated on the relationship between infertility and marital quality [8, 9, 11, 12, 16, 17, 18]; two studies concentrated on the relationship between infertility, self-compassion, and marital quality [9, 16]; and, one study focused on the interactions between infertility and coping style [5].

There was no association between self-compassion and marital quality. It was concluded that self-compassion could play a mediating role in the diagnosis of infertility and can lead to improved mental health status. Furthermore, coping techniques directed at addressing negative effects and stressors generally were connected with infertility; the infertility treatment process could have the potential to progress mental health and social and marital relationship in infertile women [5].

The quality of studies was graded by the GRADE from the Cochrane handbook [22]. Except for two of the studies which had low quality, the rest included medium- and high-quality primary studies. The studies were tested concerning design, risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication.

The most recent systematic review on the relationship between psychological factors in infertile women was performed in 2015 and included 172 infertile women (primary & secondary) [5]. The latest review concluded that both groups of infertile women reported similar levels of self-compassion, global fertility-related stress, and subjective wellbeing. It was also revealed that self-compassion plays as a mediator in the relationship between wellbeing and parenting needs in infertile women. Furthermore, self-compassion mediated the relationship between social anxiety and wellbeing among infertile females [5].

Infertility and the subsequent problems are associated with not having a child as well as issues, such as family and marital turmoil; the feeling of rejection from others; blaming oneself and others, and various personality, psychological, family, and communication function impairments. The financial burden of biopsychological rehabilitation, required for infertile groups is increasing worldwide. Some infertility-induced problems could be the excessive costs of infertility treatment; constant worrying about the effectiveness of the treatment and the process; the fear of family breakdown, and the loss of interest in the spouse. According to some studies, the marital quality of infertile women decreases; in some cases, it leads to divorce while the couple is struggling with infertility problems [23].

Infertility exposes couples to sexual and marital problems, reduced intimacy, guilt, depression, and feelings of emptiness. Besides, these psychological and emotional complications could be considered among the causes of infertility [24]. Marital quality is considered among the major aspects of infertile women’s life; it plays an essential role in evaluating and predicting family communication’s overall quality [15]. Moreover, marital quality has a multidimensional concept. It includes various aspects of a couple’s communication, such as satisfaction, adjustment, cohesion, happiness, and commitment [25].

Studies suggested that infertile couples are less likely to cope with their problems than fertile couples are. This is mostly because they anticipate negative outcomes. As this pattern continues, important issues, such as solving everyday life problems, family finances, and even emotional issues, such as expressing love, emotional intimacy, and unresolved sexual intimacy remain unresolved. Researchers believe that infertile couple’s marital satisfaction and marital quality are significantly lower, compared to fertile couple’s marital satisfaction level, which could be associated with their sociodemographic and healing experience [9, 11].

Self-compassion requires being kind and understanding toward self when one suffers, fails, or feels inadequate, rather than disregarding pain or self-punishment and self-criticism. Moreover, it indicates being patient and kind to others and having a non-judgmental understanding of them. This idea reflects that one’s life experiences and problems are part of the issues that others are experiencing. Self-compassion is associated with feelings of self-love and concern for others; however, it does not covey self-centeredness or preference for one’s needs [25]. Studies revealed that women who are less likely to self-blame for failure and are more forgiving of perceived shortcomings enjoy a better mental health status [8]. Self-compassion mediates the association between social anxiety and psychological wellbeing in infertile women. This is because of the social problems, including social identity and isolation which infertile women experience while encountering infertility [5].

Emotion is one of the most critical elements of behavior. Emotional experiences can boost energy and strength concerning one’s behavior. Furthermore, emotion is the most crucial regulator of psychosocial, occupational, and educational functions. Every emotional experience is also of an emotional aspect. Some studies demonstrated that emotional experience has positive and negative dimensions [4, 14, 26]. These characteristics represent different dimensions of emotion [27]. The high rates of discontinuing infertility treatment are implicated by psychological complications in coping with the emotional necessities of this intervention [28]. Positive affect reflects one’s passion for life and determines how active and alert they feel. High levels of positive affect designate greater levels of energy, complete focus, and enjoyable employment; however, low levels of positive affect indicate sadness and exhaustion. Negative affect is a general dimension of inner distress and unpleasant employment. Besides, it conveys unpleasant moods, such as irritation, hatred, blame, fear, and anxiety; however, low levels of negative affect are associated with relaxation and comfort [10]. Positive affect and negative affect can concurrently co-occur, representing that they do not exist at the opposite ends of a scale [26].

The co-authors characterized the combination of experiential indication from the included articles into 4 groups; self-compassion, positive and negative affect, marital quality, and infertile women. These groups were considered after the analysis and in-depth argument of cohesions and dissimilarities in study findings.

4. Discussion

The present review study investigated self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality in infertile women. We also attempted to find a better understanding of psychological factors affecting infertile women’s mental health; accordingly, different promoting behaviors were explored to help them cope with challenging and stressful infertility treatment. A review of studies has highlighted that infertile couples, especially infertile women, are more prone to using avoidance mechanisms, experimental avoidance, and coping styles with the least emotion and distance to cope with the problems when undergoing infertility treatment. Additionally, the odds of using avoidant coping strategies are higher in infertile couples, compared to their fertile counterparts [16].

Researchers have documented that marital quality can adversely and significantly predict negative affect in women. The stronger the marital quality, the greater the commitment and emotional exchange between the couples; the more the women’s emotional needs; and the higher their negative affect decreases. Negative affect seems to divert attention to internal worries and prevent emotional exchange between couples; thus, increasing the level of marital quality and women’s life satisfaction as well as reducing their negative affect [29]. Although marital quality is complicated in infertile couples, some studies have indicated a strong marital quality in infertile couples. According to studies, the stages of diagnosis and treatment of infertility facilitate communication and intimacy between couples; thus, they will feel more intimate with each other [5]. Moreover, other aspects, such as the age of infertile couples, sexual satisfaction, the coordination of couples’ perception of infertility, and their educational level are related to marital quality [12, 14]. Infertility counseling with infertile couples concerning the sexual response cycle and sexual health can improve sexual satisfaction and marital quality among infertile females [20]. Scholars also found that teaching life quality skills significantly improve marital quality among infertile women [30].

A review of some studies indicated that fertile women experience a higher positive affect, compared to infertile females. Moreover, there was a significant difference in positive and negative affect between fertile and infertile women. Studies demonstrated that self-compassion mediates positive and negative affect by affecting infertility stress and reduces stress levels in infertile women. Infertile women experience negative affect, e.g. anger, frustration, and fear due to stress-induced infertility. Accordingly, self-compassion can help infertile women with reducing negative affect and preparing the right environment for positive affect, e.g. happiness and interest. Infertile women with high levels of self-compassion experience greater positive affect and less negative affect. Moreover, lower levels of self-compassion in infertile women indicate a higher extent of negative affect [5].

Women with positive affect are usually enthusiastic, energetic, confident, active, and alert. Positive affect positively impacts one’s interaction with others and surroundings. Positive affect is an integral part of everyday life. Furthermore, such emotions help individuals process emotional data to solve problems, make the right planning, and accurately and efficiently achieve success [4]. Researchers consider self-compassion as a fundamental construct in emotion regulation and balance; they investigated if it is a function of adaptive strategies for organizing emotions by reducing negative affect and creating positive affect, e.g. kindness and social cohesion [25]. According to studies, self-compassion significantly affects the relationship between positive and negative affect and hope in infertile women [14]. There was a positive and significant relationship between psychological health, self-compassion, and marital quality in couples. Infertile couple’s self-compassion can explain the changes in their marital adjustment [9]. Gallardo [30]indicated that self-compassion plays a mediating role between inner shame and stress induced by infertility. Besides, it can mediate the effect of marital quality on infertility-induced stress [9]. Another study found that self-compassion played an essential mediating role in social anxiety and mental health among infertile women. This is due to their complex social identities and social isolation. Infertility can also help infertile women as an emotion regulation strategy; it is also a characteristic in accelerating repression, self-blame, or other-blame [31].

Infertility stress, especially in women, can be a combination of internal self-compassion and the lack of support for others; thus, self-compassion, as an internal factor, can develop emotion through self-awareness rather than judging or criticizing one’s shortcomings and inadequacies [14]. Mantelou and Karakasidou [29] examined the relationship between self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and life satisfaction. Subsequently, they found that promoting self-compassion enhances increases the level of positive affect; as a result, self-compassionate individuals experience a high extent of positive affect. Individuals with high levels of self-compassion resolve interpersonal conflicts by considering the needs of self and others. Infertile women can improve their communication with others through self-compassion; consequently, they will gain further support from others. Thus, the odds of assessing the problems of infertility as stressful decreases. Eventually, such measures help them to promote their level of self-compassion and reduce the stress of the infertility treatment process [25].

Self-compassion-based treatment and self-judgment reduction could be implemented to reduce infertility-induced stress and improve compatibility and marital quality in infertile couples [5]. These findings highlight the significance of paying attention to positive psychological variables when working with infertile women; research indicated that increasing interpersonal skills improve marital quality [29].

There is a conspicuous absence in the literature when trying to comprehend the relationship between self-compassion and marital quality in infertile women as well as the association between self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality altogether. For instance, studies distinguishing the direct or indirect relationship between self-compassion and marital quality in infertile women are scarce. Moreover, there is inadequate data about the age group of infertile women in most of the studies which can limit the investigations. This is mostly because the age group that goes through infertility treatment matters, especially due to a golden period for achieving a successful result. Future studies need to address the direct or indirect relationship between self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality in infertile women. Additionally, there is a necessity to investigate the age group, education, and source of infertility in infertile women to reach accurate results.

The findings of this systematic review indicated a large gap in the development of the complication of the design of studies, i.e., ambiguous. To continue to shape evidence concerning the relationship between self-compassion, positive and negative affect, and marital quality in infertile women, studies must reflect the direct or indirect relationship between specific variables. Such characteristics include self-compassion and positive and negative affect and marital quality (3 variables) to understand the precise intervention design and testing.

This systematic review was directed with precision and devotion to the PRISMA guidelines. Constructed on careful evaluations of the studies included in this review, the results of the synthesis are rationally presented. The included studies also provided a general picture of the universal difficulties of coping with infertility in women/couples to the readers. Moreover, being geographically dispersed could be counted as a strength of this systematic review.

The obtained data were restricted to rational implications from included studies. It was also recognized that not all studies were planned to contain the identified elements, i.e., significant to marital quality in infertile women. The wide-ranging geographic basis of the study also limited concluding any particular healthcare system or culture.

5. Conclusion

Based on this systematic review, some studies assumed that self-compassion could play a mediating role between positive and negative affect and marital quality among infertile women. The present gaps in the literature are linked to interventions, age, culture, and the duration of experiencing infertility. Besides, there is insufficient research based on the relationship between more than two psychological variables.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University Science and Research Branch (Code: IR.IAU.SRB.REC.1398.021).

Funding

The authors received no financial support for this study.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and Supervision: Sepideh Dadkhah, Jamshid Jarareh, Firoozeh Akbari Asbagh; Methodology: Sepideh Dadkhah; Investigation, Writing – original draft, and Writing – review & editing: All authors; Data collection and Data analysis: Sepideh Dadkhah

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all scholars helped us in data collection and writing this systematic and meta-analysis review.

References

- Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, de Mouzon J, Ishihara O, Mansour R, Nygren K, et al. International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART) and the World Health Organization (WHO) revised glossary of ART terminology, 2009. Fertility and Sterility. 2009; 92(5):1520-4. [DOI:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.09.009] [PMID]

- Cousineau TM, Domar AD. Psychological impact of infertility. Best practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2007; 21(2):293-308. [DOI:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.12.003] [PMID]

- Greil AL, Slauson-Blevins K, McQuillan J. The experience of infertility: a review of recent literature. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2010; 32(1):140-62. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01213.x] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kong L, Fang M, Ma T, Li G, Yang F, Meng Q, et al. Positive affect mediates the relationships between resilience, social support and posttraumatic growth of women with infertility. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2018; 23(6):707-16. [DOI:10.1080/13548506.2018.1447679] [PMID]

- Raque-Bogdan TL, Hoffman MA. The relationship among infertility, self-compassion, and well-being for women with primary or secondary infertility. Psychology of women quarterly. 2015; 39(4):484-96. [DOI:10.1177/0361684315576208]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009; 6(7):e1000097. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Afshani SA, Abooei A, Abdoli AM. Self-compassion training and psychological well-being of infertile female. International Journal of Reproductive Biomedicine. 2019; 17(10):769-74. [DOI:10.18502/ijrm.v17i10.5300] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Dargahi S, Mohsenzade F, Zahrakar K. [The effect of positive thinking training on psychological well-being and perceived quality of marital relationship on infertile women (Persian)]. Positive Psychology Research. 2015; 1(3):45-58. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=579063

- Izadi N, Sajjadian I. [The relationship between dyadic adjustment and infertility-related stress: The mediated role of self-compassion and self-judgment (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatric Nursing (IJPN). 2017; 5(2):15-22. [DOI:10.21859/ijpn-05023]

- Kormi Nouri R. [A cross-cultural study about positive and negative emotions and well-being in infertile women (Persian)]. Clinical Psychology Studies. 2017; 7(28):31-9. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=606506

- Safaei Nezhad A, Ebrahimi L, Vakili MM, Kharaghani R. Effect of counseling based on the choice theory on irrational parenthood cognition and marital quality in infertile women: A randomized controlled trial. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 2020; 56(1):141-8. [DOI:10.1111/ppc.12392] [PMID]

- Monga M, Alexandrescu B, Katz SE, Stein M, Ganiats T. Impact of infertility on quality of life, marital adjustment, and sexual function. Urology. 2004; 63(1):126-30. [DOI:10.1016/j.urology.2003.09.015] [PMID]

- Onat G, Beji NK. Marital Relationship and quality of life among couples with infertility. Sexuality and Disability. 2012; 30:39-52. [DOI:10.1007/s11195-011-9233-5]

- Raque-Bogdan T. Self-compassion, hope, and well-being of women experiencing primary and secondary infertility: An application of the biopsychosocial model [MSc. Thesis]. United States: University of Maryland; 2010. [DOI:10.1037/e622022010-001]

- Peterson BD, Pirritano M, Christensen U, Schmidt L. The impact of partner coping in couples experiencing infertility. Human Reproduction (Oxford, England). 2008; 23(5):1128-37. [DOI:10.1093/humrep/den067] [PMID]

- Galhardo A, Cunha M, Pinto-Gouveia J, Matos M. The mediator role of emotion regulation processes on infertility-related stress. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2013; 20(4):497-507. [DOI:10.1007/s10880-013-9370-3] [PMID]

- Wang K, Li J, Zhang JX, Zhang L, Yu J, Jiang P. Psychological characteristics and marital quality of infertile women registered for in vitro fertilization-intracytoplasmic sperm injection in China. Fertility and Sterility. 2007; 87(4):792-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.07.1534] [PMID]

- Van Der Merwe E, Greeff AP. Infertility-related stress within the marital relationship. International Journal of Sexual Health. 2015; 27(4):522-31. [DOI:10.1080/19317611.2015.1067275]

- Sutton E, Schonert-Reichl KA, Wu AD, Lawlor MS. Evaluating the reliability and validity of the self-compassion scale short form adapted for children ages 8-12. Child Indicators Research. 2018; 11(4):1217-36. [DOI:10.1007/s12187-017-9470-y]

- Crawford JR, Henry JD. The positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS): Construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2004; 43(Pt 3):245-65. [DOI:10.1348/0144665031752934] [PMID]

- Ward PJ, Lundberg NR, Zabriskie RB, Berrett K. Measuring marital satisfaction: A comparison of the revised dyadic adjustment scale and the satisfaction with married life scale. Marriage & Family Review. 2009; 45(4):412-29. [DOI:10.1080/01494920902828219]

- Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. New Jersey: Wiley; 2019. [DOI:10.1002/9781119536604]

- Baer RA, Lykins ELB, Peters JR. Mindfulness and self-compassion as predictors of psychological wellbeing in long-term meditators and matched nonmeditators. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2012; 7(3):230-8. [DOI:10.1080/17439760.2012.674548]

- Clark LA, Watson D. Mood and the mundane: Relations between daily life events and self-reported mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988; 54(2):296-308. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.54.2.296] [PMID]

- Neff KD. Self-Compassion, self-esteem, and well-being. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2011; 5(1):1-12. [DOI:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00330.x]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988; 54(6):1063-70. [DOI:10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063] [PMID]

- Troxel WM, Robles TF, Hall M, Buysse DJ. Marital quality and the marital bed: Examining the covariation between relationship quality and sleep. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2007; 11(5):389-404. [DOI:10.1016/j.smrv.2007.05.002] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Abolghasemi A, Rajabi S, Sheikhi M, Kiamarsi A, Sadrolmamaleki V. Comparison of resilience, positive/negative affect, and psychological vulnerability between Iranian infertile and fertile men. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. 2013; 7(1):9-15. [PMCID]

- Mantelou A, Karakasidou E. The effectiveness of a brief self-compassion intervention program on self-compassion, positive and negative affect and life satisfaction. Psychology. 2017; 8(4):590-610. [DOI:10.4236/psych.2017.84038]

- Cunha M, Galhardo A, Pinto-Gouveia J. Experiential avoidance, self-compassion, self-judgment and coping styles in infertility. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare: Official Journal of the Swedish Association of Midwives. 2016; 10:41-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.srhc.2016.04.001] [PMID]

- Teilegen A. Structures of mood and Ppersonality and their relevance to assessing anxiety, with an emphasis on self-report. In: Tuma AH, Maser J, editors. Anxiety and the anxiety disorders. United Kingdom: Routledge; 2019. [DOI:10.4324/9780203728215-49]

Article type: Reviews |

Subject:

Psychology

Received: 2020/08/31 | Accepted: 2021/02/26 | Published: 2021/03/30

Received: 2020/08/31 | Accepted: 2021/02/26 | Published: 2021/03/30

Send email to the article author