Volume 22, Issue 4 (December 2024)

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2024, 22(4): 645-654 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.USWR.REC.1400.072

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Sayadnasiri M, Khodaei Ardakani M R, Nazeri Astaneh A, Noroozi M, Deilami M. Investigation of Clinical Features, EEG Findings, and Brain Imaging in Psychiatric Patients With Epilepsy at Razi Psychiatric Hospital. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2024; 22 (4) :645-654

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1779-en.html

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1779-en.html

Mohammad Sayadnasiri1

, Mohammad Reza Khodaei Ardakani1

, Mohammad Reza Khodaei Ardakani1

, Ali Nazeri Astaneh1

, Ali Nazeri Astaneh1

, Mehdi Noroozi2

, Mehdi Noroozi2

, Mostafa Deilami *1

, Mostafa Deilami *1

, Mohammad Reza Khodaei Ardakani1

, Mohammad Reza Khodaei Ardakani1

, Ali Nazeri Astaneh1

, Ali Nazeri Astaneh1

, Mehdi Noroozi2

, Mehdi Noroozi2

, Mostafa Deilami *1

, Mostafa Deilami *1

1- Department of Psychiatry, School of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 466 kb]

(675 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2523 Views)

Full-Text: (486 Views)

Introduction

Epilepsy, a chronic disorder characterized by recurrent seizures, arises from the brain dysfunction due to excessive abnormal neuronal electrical discharges [1]. In 1870, scientists reported that seizures were caused by overcharging of nervous tissue in muscles [2]. Since ancient times, physicians have acknowledged the link between epilepsy and psychiatric disorders, although, in contemporary times, this relationship has been perceived as tenuous, with research in this domain remaining limited. However, the development of new antiepileptic and psychiatric drugs and new neuroimaging techniques makes it increasingly important to understand the relationship between epileptic seizures and the pathology of psychiatric disorders [3]. For a long period (in the modern world) epilepsy was considered a purely neurological disease involving the central nervous system, and physicians focused primarily on achieving a seizure-free state. Recent studies over the past decades have revealed that seizures represent just one aspect of epilepsy. Cognitive and psychiatric disorders are also prevalent among these patients, with one in three experiencing significant cognitive-psychiatric issues, which can sometimes overshadow convulsive symptoms in their clinical presentation [4].

Psychiatric conditions affect 32% to 41% of epileptic patients, often leading to a worse prognosis compared to those without psychiatric issues. Psychiatric disorders can emerge before, during, or after an epilepsy diagnosis, complicating treatment and diagnosis while worsening prognosis, increasing healthcare utilization, and imposing significant socioeconomic burdens globally due to chronic disability, dependence, and mortality. The strong correlation between psychiatric disorders and epilepsy highlights the necessity of investigating psychiatric disease risk factors and their temporal relationships in affected patients [5]. Some scholars argue that this connection does not imply that epilepsy causes psychiatric disorders or vice versa, but rather suggests a shared pathological pathway that culminates in both epilepsy and psychiatric conditions [6]. In most instances, psychiatric disorders manifest before the onset of epilepsy, negatively impacting the course of epilepsy and its future treatment, especially since epilepsy diagnosis is often delayed in these patients, leading to untimely treatment. Studies have shown that having a history of mood disorders before the onset of epilepsy can increase the risk of refractory epilepsy [7, 8]. Also, family or personal history of psychiatric disorders increases the likelihood of psychiatric side effects following the use of antiepileptic drugs [4, 9]. Studies also suggest that a history of anxiety and mood disorders may elevate the risk of seizures during stressful situations Furthermore, the quality of life (QoL) for epileptic patients declines if they suffer from psychiatric disorders, with the coexistence of mood disorders and anxiety in an epileptic patient being a strong predictor of a reduced QoL, imposing greater economic burdens on the patient, their family, and society [10, 11]. To gain insights into neurophysiological disorders, the electroencephalographic method is employed to differentiate neuropsychiatric patients from the healthy population [12]. Electroencephalography (EEG) allows for the recording and observation of brain electrical potentials stemming from the neural activity, known as an electroencephalogram. EEG signals reflect all mental and physical brain activities, enabling the recording of various brain activity patterns such as beta waves (12 to 30 Hz: High alertness), alpha (8 to 12 Hz: Wakefulness), theta (4 to 8 Hz: Fatigue), and delta (0.5 to 4 Hz: Low alertness) [13].

In previous studies, the rate of depression in the general population was 6 to 19%, and in epileptic patients 9 to 37%. The incidence of anxiety disorders in the general population has been reported 7-11% and in epileptic patients 11 to 25%. In a meta-analysis, the prevalence of psychosis in epileptic patients was estimated at 5.6%. Personality disorders also seem more prevalent in epileptic individuals compared to the general population, ranging from 6 to 14%, and in some studies, as high as 38% [8]. Epilepsy leads to poor academic performance, increases unemployment rates, and reduces patients’ incomes. Marriage and fertility rates are lower in epileptic patients, depriving them of a normal family and social life. Beyond the familial, social, and economic consequences of epilepsy, some studies have indicated that epilepsy is more likely to occur in individuals with low socioeconomic status, complicating psychiatric and cognitive issues [14, 15]. Therefore, epilepsy cannot be regarded solely as an organic disease affecting the central nervous system. The psychiatric dimensions are crucial in epileptic patients, influencing the treatment prognosis and the patients’ QoL on individual, familial, and societal levels. Although some studies have been conducted in this field in the last two decades, further studies are essential to uncover unknown aspects of this relationship and to underscore the importance of addressing psychiatric disorders in epileptic patients [4].

The prevalence of epilepsy in our country is higher than the global average due to the high rate of road accidents and survivors of the imposed war, but there is not enough information about the prevalence of cognitive and psychiatric disorders in these patients. Razi Psychiatric Center (Tehran, Iran), being one of the foremost facilities for treating and managing acute and chronic psychiatric patients, encounters individuals with seizures and epilepsy daily. This frequent occurrence can be linked to the scarcity of local clinical data on the coexistence of epilepsy and psychiatric disorders, coupled with inadequate awareness among physicians and the healthcare system regarding these conditions, complicating effective treatment for these patients. Therefore, conducting a comprehensive study to examine the various aspects of concurrent seizure-epilepsy and psychiatric disorders, utilizing EEG and brain imaging techniques at this center, stands as a significant step towards enhancing the mental health care of epilepsy patients. It will also improve treatment programs for these patients. Therefore, we investigated the clinical features, EEG, and brain imaging findings in psychiatric patients with epilepsy at Razi Psychiatric Hospital.

Materials and Methods

This descriptive retrospective study examined 94 files of epileptic patients with psychiatric disorders at Razi Psychiatric Hospital, affiliated with the Tehran University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, who were admitted between 2018 and 2020. Patients were diagnosed by clinical and physical examinations, EEG findings, and MRI imaging. The inclusion criteria were a) Patients with seizures confirmed by at least one neurologist based on clinical criteria, and b) Those with psychiatric illnesses confirmed by at least one psychiatrist based on clinical criteria. The exclusion criteria included: 1) Patients not assessed for a psychiatric disorder, 2) Patients diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder but not hospitalized, and 3) Patients lacking enough clinical, EEG or neuroimging data that could confirm seizure diagnosis. The information recorded in the files included age, sex, marital status, education, occupation, type of epilepsy, epilepsy etiology, EEG and brain imaging findings, the occurrence of epilepsy before psychiatric illness, and the use of antiepileptic drugs. Psychiatric disorders in this study included bipolar and related disorders, developmental disorder, anxiety, schizophrenia depressive, obsessive-compulsive, and related disorders, as well as substance and alcohol abuse disorder. Electroencephalogram changes examined were normal electroencephalogram, focal slowing, diffuse slowing, focal epileptiform discharges of focal attacks, and bilateral epileptiform discharges. Brain imaging changes studied included normal imaging, cerebral cortical lesions, white matter lesions, and cerebral atrophy. This information is recorded in HIS system of the hospital and were studied and data were collected by demographic checklist, epilepsy scale: The checklist used was made by DiIorio et al [16] and included personal characteristics, mental disorders, epilepsy and seizures. The Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney non-parametric tests were employed to compare the mean scores of variables and SPSS software, version 21 was used for data analysis.

Results

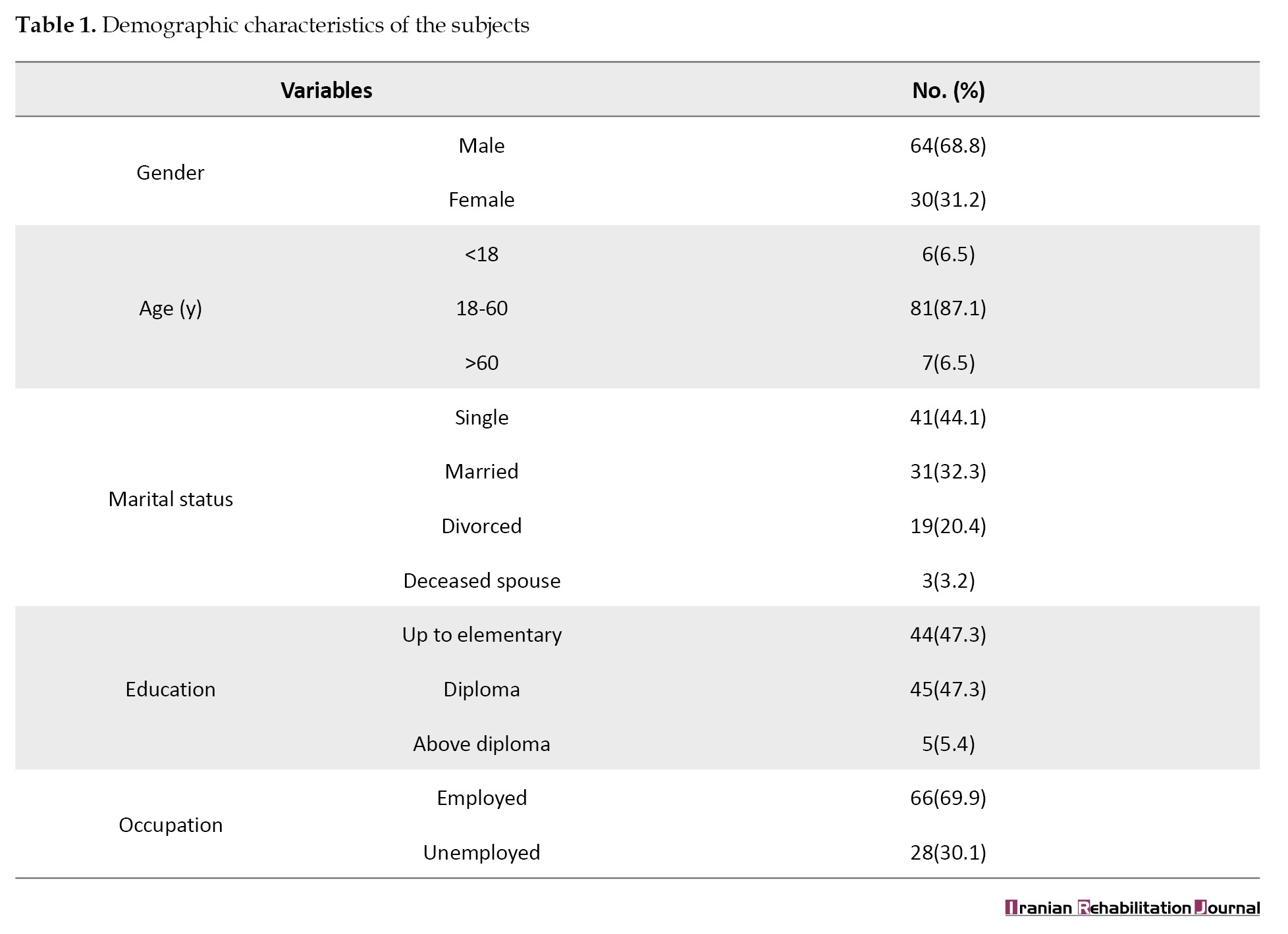

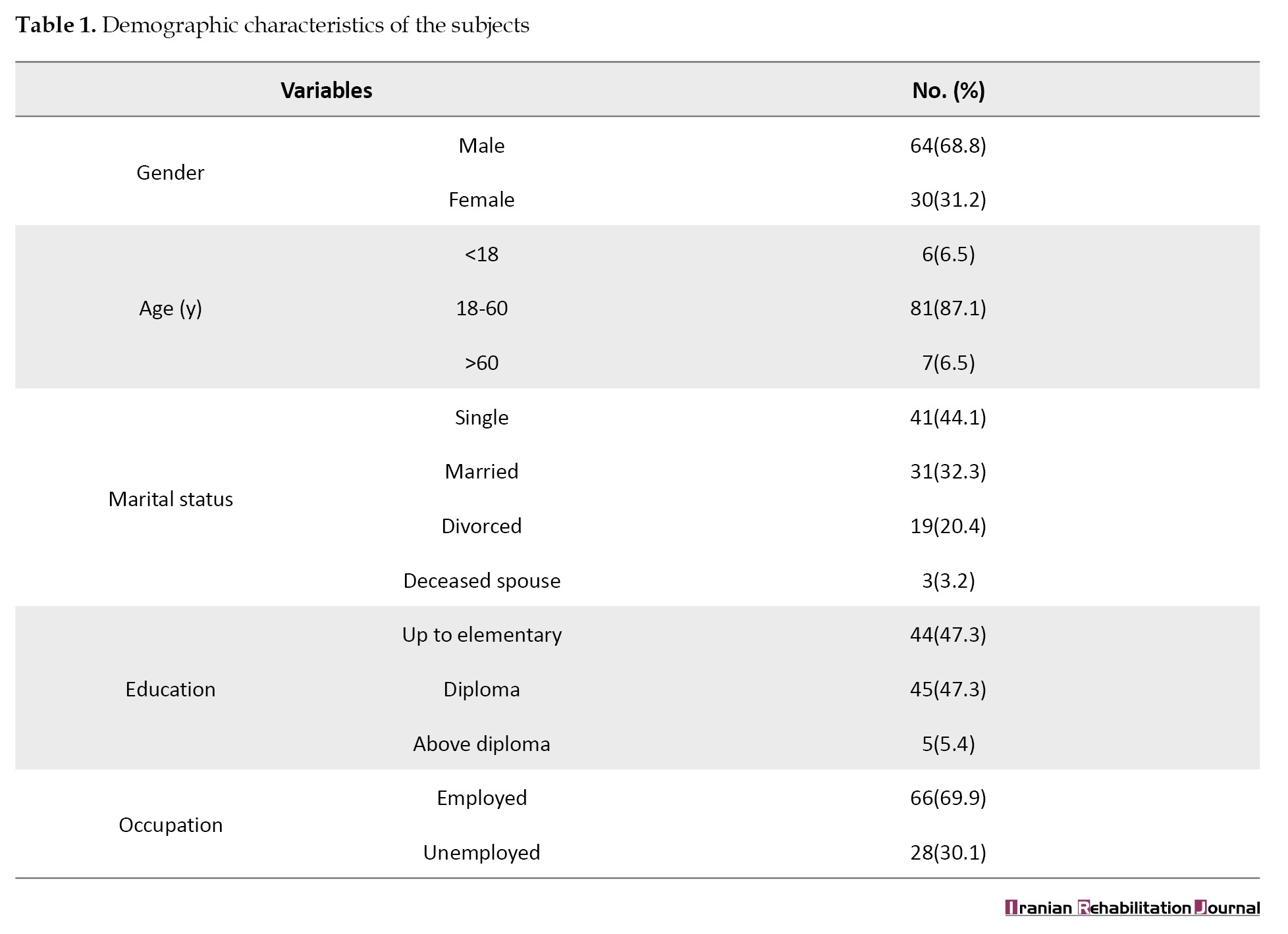

According to findings of present study, out of 94 epileptic patients, 64 were male (68.8%) and 30 were female (31.2%). Six individuals (6.5%) were under 18 years old, 81(87.1%) were aged between 18 and 60 years, and 7(6.5%) were over 60 years. Forty-one patients (44.1%) were single, 31(32.3%) were married, 19(20.4%) were divorced, and 3(3.2%) had a deceased spouse. Forty-four (47.3%) had education up to the 6th grade, 45(47.3%) had education between the 6th grade and diploma level, and 5(5.4%) had education beyond the diploma level. Also, 28 people (30.1%) were unemployed and 66 people (69.9%) were employed (Table 1).

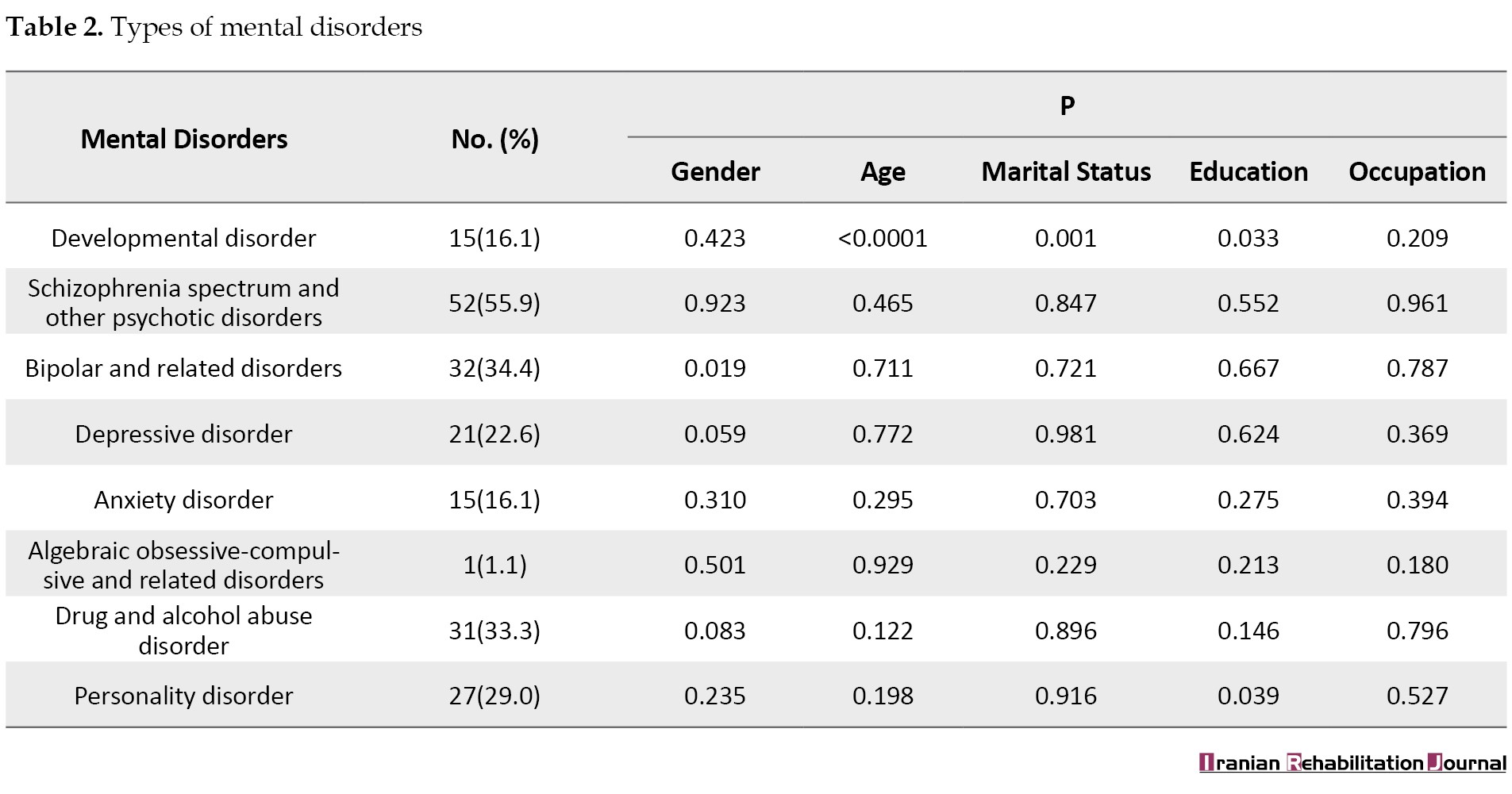

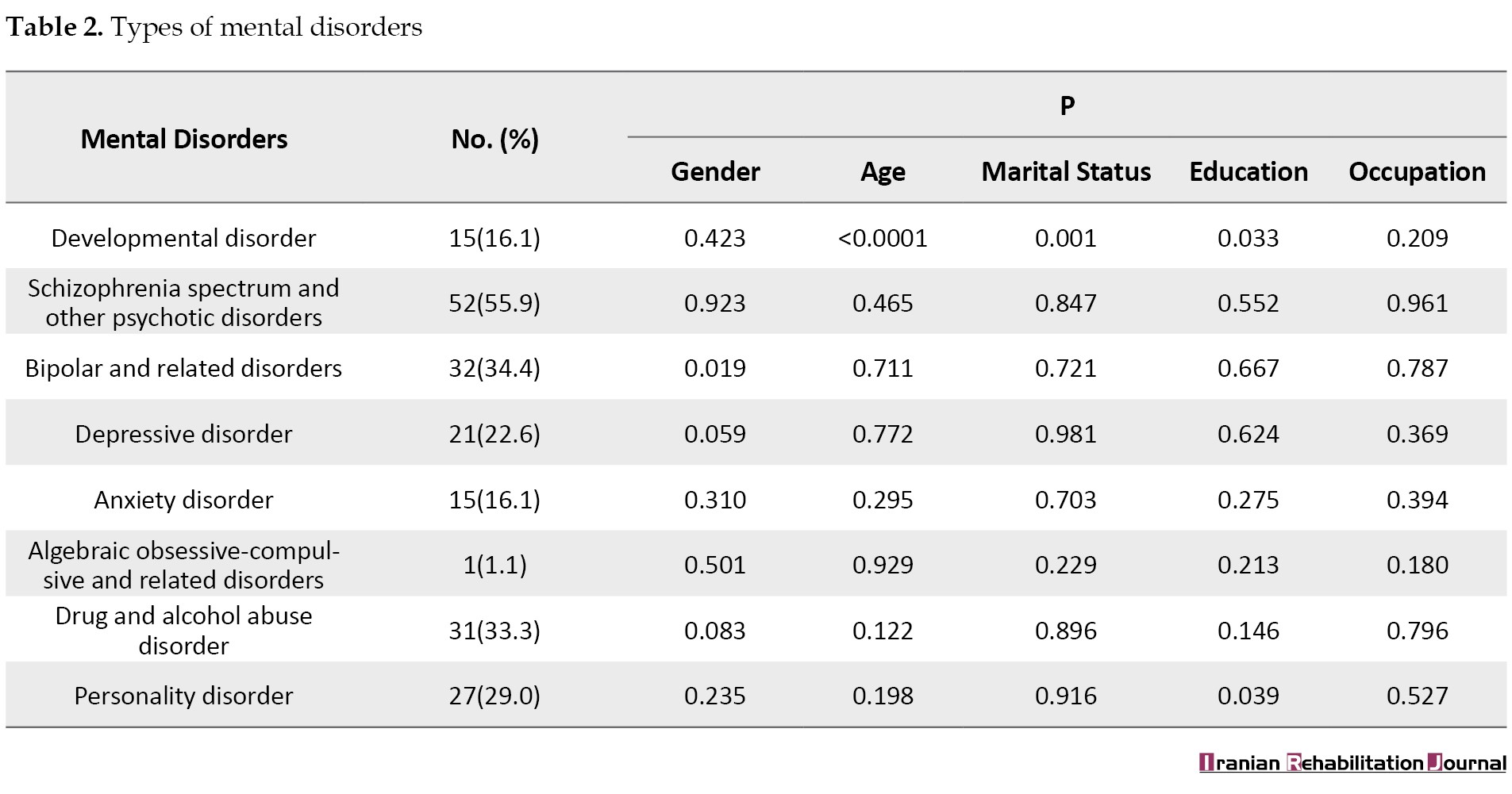

The findings for epilepsy indicated that 9 patients (4.5%) had focal epilepsy, 24(12.0%) generalized epilepsy, 34(17.0%) focal and generalized epilepsy, and 26(13.0%) had epilepsy of unknown classification. The examination of psychiatric disorders revealed that 15 patients (16.1%) had developmental disorders, 52(55.9%) schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders, 32(34.4%) bipolar and related disorders, 21(22.6%) depressive disorder, 15(16.1%) anxiety disorder, 1(1.1%) obsessive-compulsive and related disorder, 31(33.3%) substance and alcohol abuse disorder, and 27(29.0%) had a personality disorder. The comparison between various psychiatric disorders showed significant differences in bipolar and related disorders between males and females (P<0.05). Developmental disorders across different age groups (P<0.01) also displayed a significant difference between married and single individuals. Additionally, developmental and personality disorders varied significantly among individuals with different educational levels (P<0.05) (Table 2).

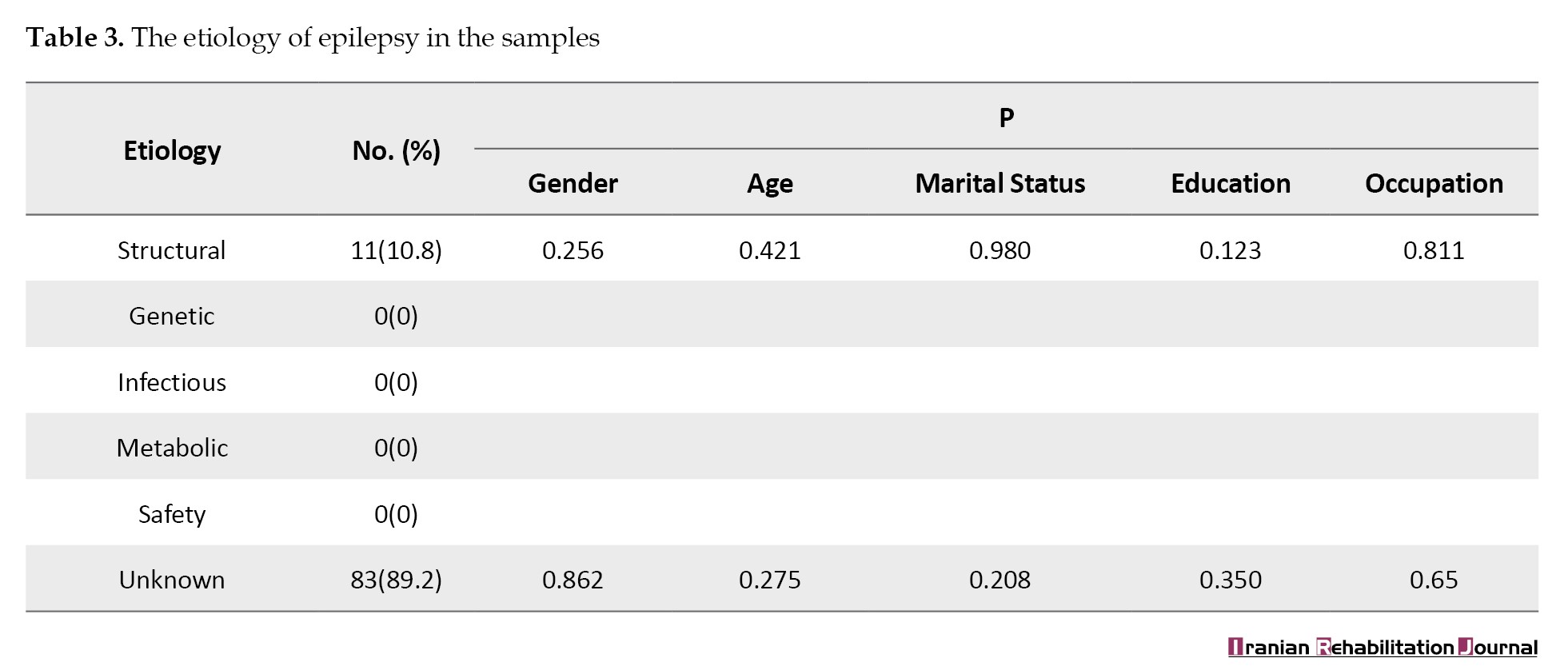

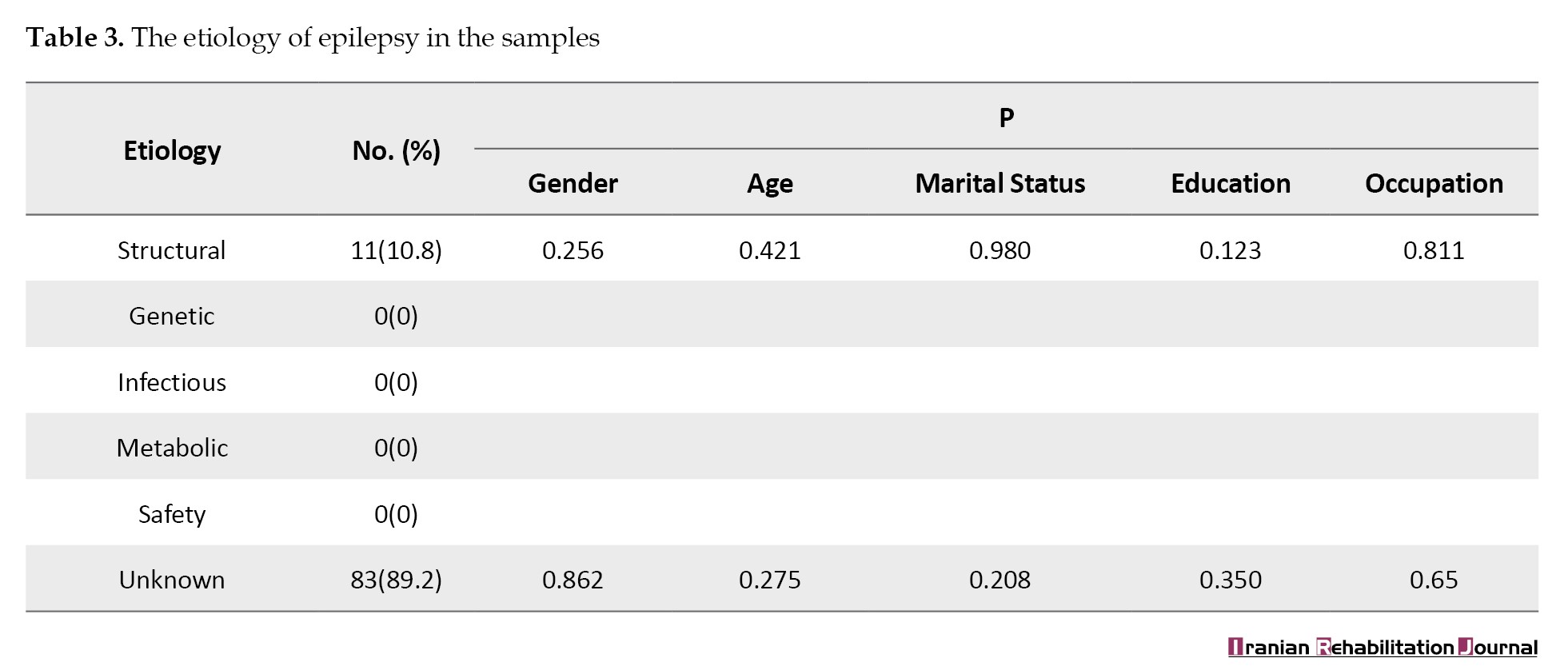

The examination of etiology in 94 epileptic patients showed that 11 patients (10.8%) had a structural etiology, while the majority (n=83; 89.2%) had an unknown etiology. The comparison of means showed no significant differences in the etiology of patients regarding gender, age, marital status, education, and occupation (Table 3).

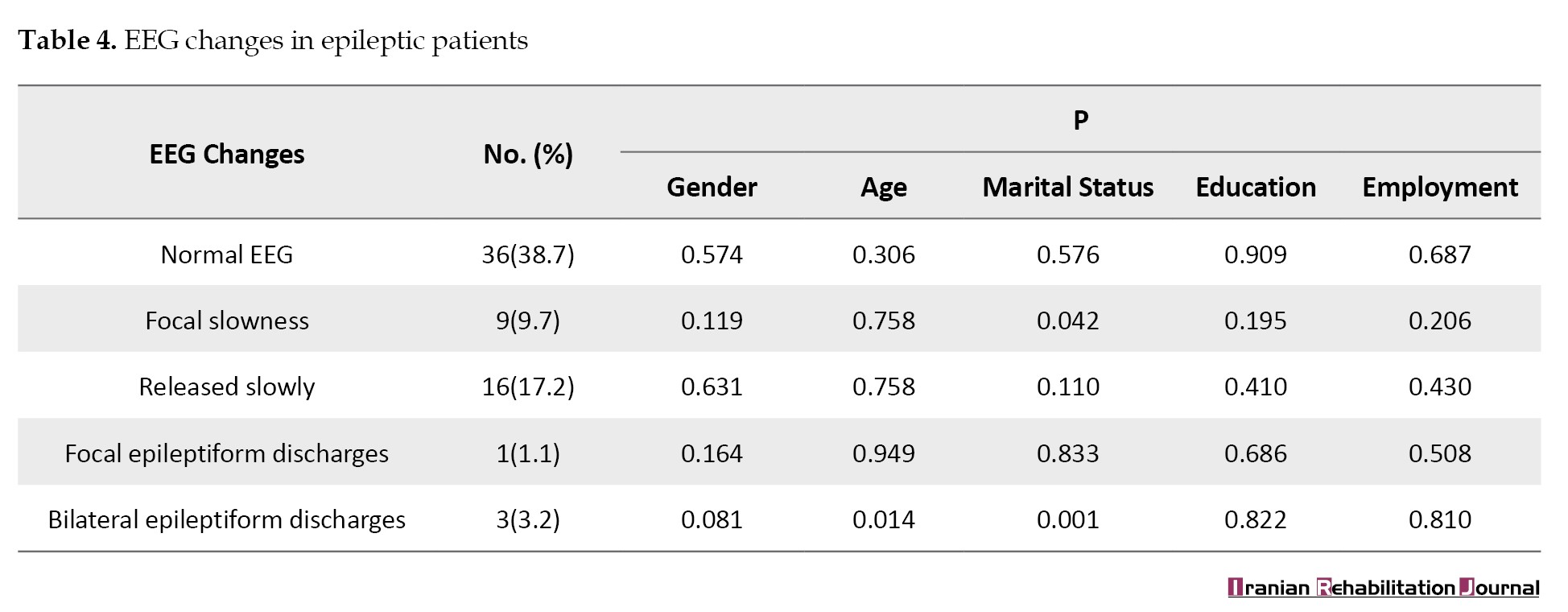

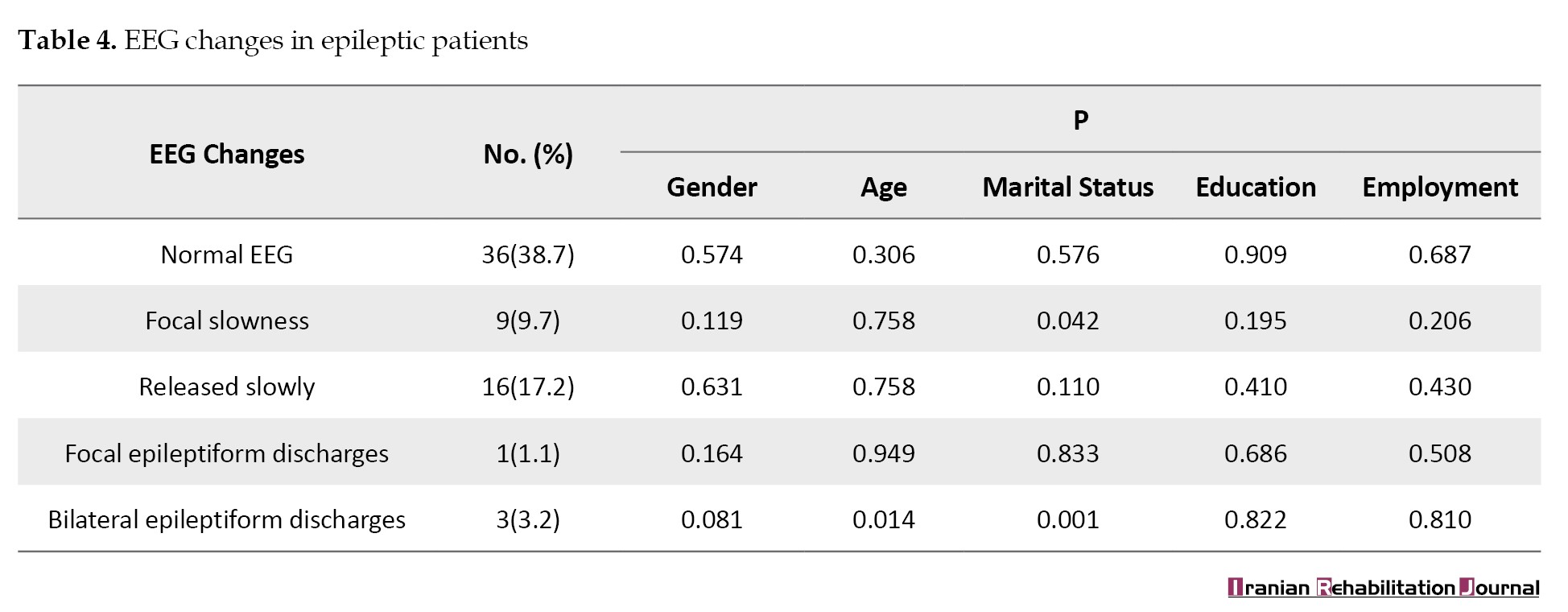

The results of EEG changes in epileptic patients showed that 36 patients (38.7%) had a normal electroencephalogram, 9 patients (9.7%) had focal slowing, 16 patients (17.2%) had diffuse slowing, 1 patient (1.1%) had focal epileptiform discharges and 3 patients (3.2%) had bilateral epileptiform discharges. The comparison of means indicated that the bilateral epileptiform discharges varied across different age groups. Focal slowness and bilateral epileptiform discharges exhibited a significant difference in relation to marital status (P<0.05; Table 4).

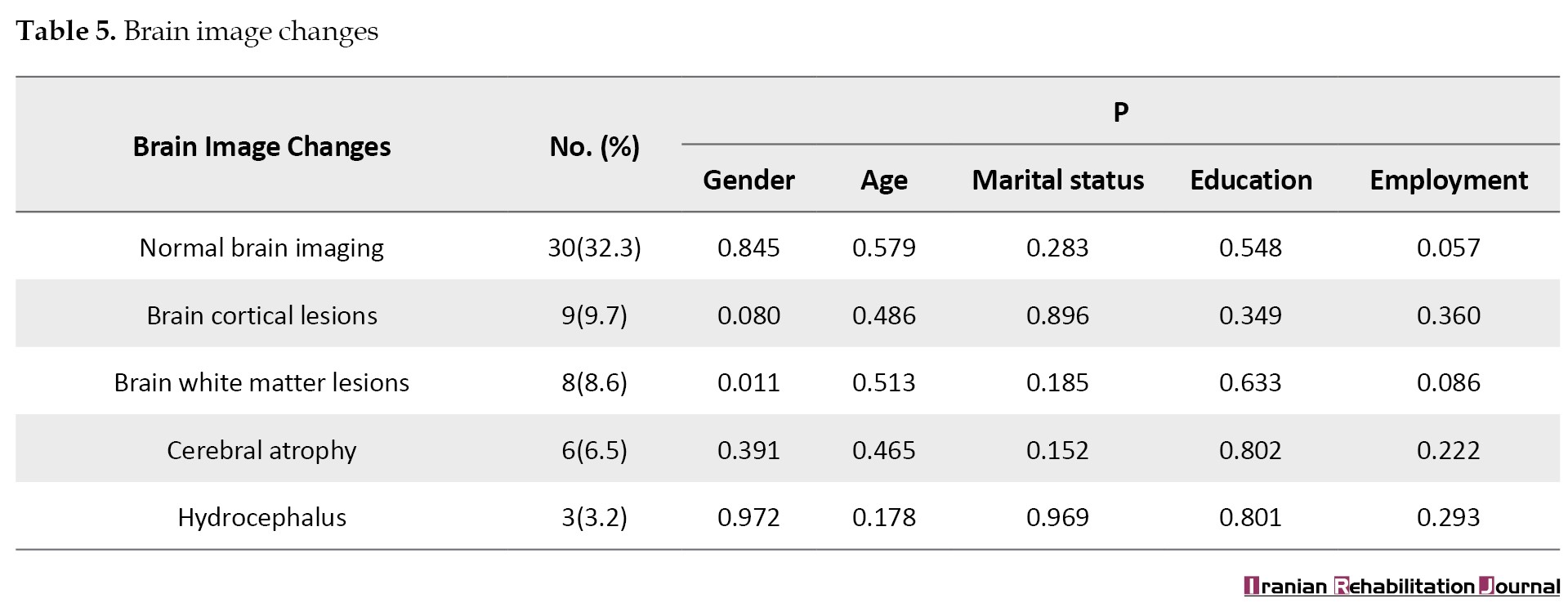

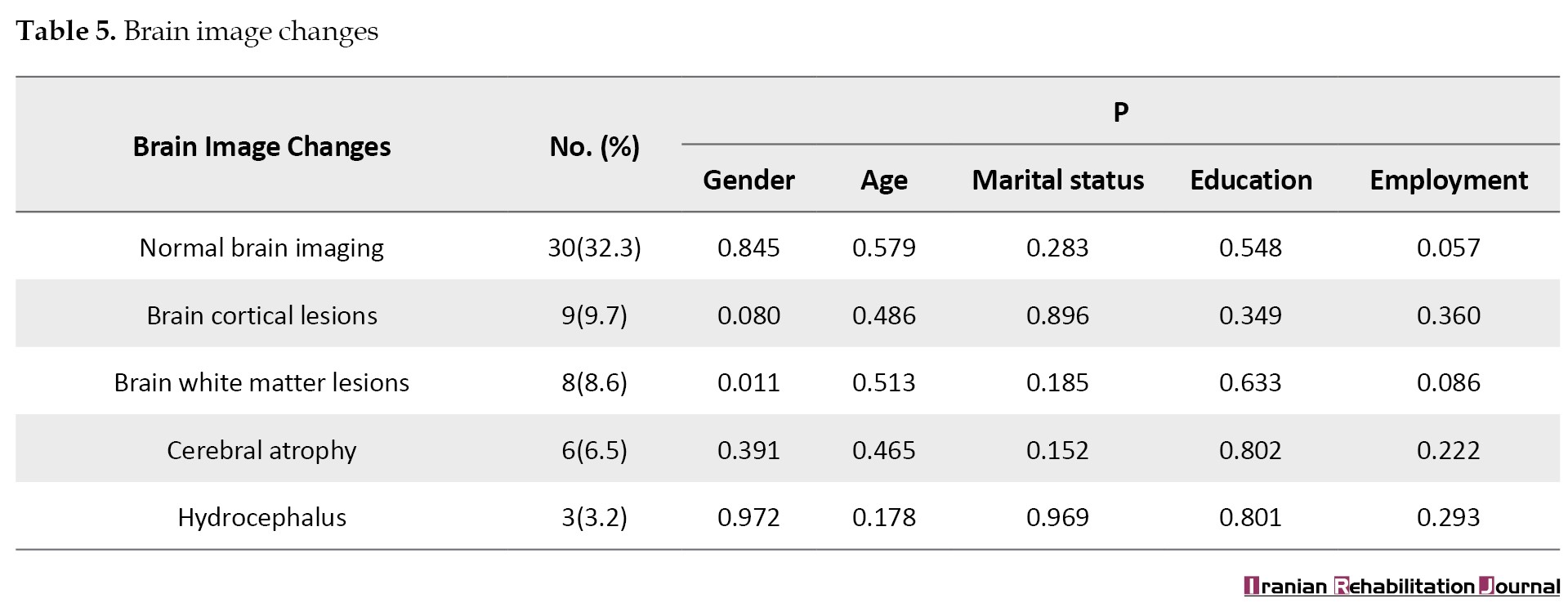

Brain imaging changes showed that 30 patients (32.3%) had normal brain imaging, 9 patients (9.7%) had cortical lesions, 8 patients (8.6%) had white matter lesions, 6 patients (6.5%) had cerebral atrophy, and 3 patients (3.2%) had hydrocephalus. The comparison of means revealed that white matter lesions in the brain differed between females and males (P<0.05) (Table 5).

Discussion

We investigated the clinical features, EEG findings, and brain imaging in psychiatric patients with epileptic disorders at Razi Psychiatric Hospital. The study found a higher prevalence of epilepsy among men compared to women. The majority of epileptic patients were aged between 18 and 60 years. Single epileptic individuals outnumbered married ones, with married patients being more numerous than those divorced, and divorced individuals exceeding those with deceased spouses. Most patients’ education levels ranged from elementary to diploma, and the majority were employed. In the study by Ghanbari Jolfaei et al. [17], the rate of being unmarried in patients with psychiatric disorders was higher compared to those married, aligning with our findings. However, the number of unemployed people was almost double that of the employed group, contrasting with our results. Also, the number of patients with elementary and diploma education was higher than those with higher education levels, consistent with our findings. The most common age range for epilepsy was between 21 to 53 years, presenting a narrower age range compared to our study. Afshari et al. [18] observed that most epileptic patients were women, differing from the results of our study, where most patients fell into the age group of 18 to 89 years. The analysis of different types of epilepsy showed that the highest frequency belonged to focal generalized epilepsy and the lowest was related to focal epilepsy, which is in line with the findings of Bahrainian et al. [19]. Our research indicated that the majority of epileptic patients were diagnosed with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, a finding consistent with previous studies exploring the epidemiological and etiological links between epilepsy and schizophrenia [19, 20]. The association between schizophrenia and epilepsy has been reported and studied by researchers for many years. Early psychiatrists like Kraepelin, who identified schizophrenia, associated it with epilepsy, while pioneers in epilepsy research like Gibbs noted an increased incidence of psychosis during the interictal phase in patients with focal epilepsy [20]. Li et al. [21] highlighted the association between epileptic disorders and schizophrenia. Adachi and Ito [22] showed a high incidence of epilepsy in schizophrenia patients (4 to 5 times higher than the general population). They found that patients with schizophrenia typically suffered from focal epilepsy and that a small number of patients with schizophrenia developed refractory epilepsy. Our study identified significant gender differences in bipolar and related disorders among psychiatric patients with epileptic disorders, Zhang et al. [23] found a close association between epilepsy and autism spectrum disorder, particularly in cases of early-onset epilepsy in women, and noted that the link between epilepsy and developmental disorders was more pronounced in younger individuals. We found a significant relationship between developmental disorder, and age, as well as marital status. Also, there was a significant association between developmental disorders and education and personality. Ghanbari Jolfaei et al. [17] found that the prevalence of psychiatric and behavioral disorders in epileptic patients is high and the type of epilepsy had no effect on the personality disorders.

The analysis of epilepsy’s etiology indicated that over half of the patients had unknown etiology and no significant difference was found between patients’ etiology and demographic factors, such as gender, age, marital status, education, and occupation. Bahrami et al. [24]reached similar findings, noting that a majority of epileptic patients had an unknown etiology, with an increase in frequency from ages 10 to 19, followed by a decrease. Nowadays, genetic advances have spread in identifying the individual causes of mental retardation and epilepsy. The genetic cause of epilepsy disorders is unclear, but certain rare epilepsy types have been linked to genetic disorders. Research into conditions such as infantile encephalopathy, infantile spasm, and myoclonic epilepsy, along with their treatment, suggests epilepsy may be associated with mental retardation. A study on the epidemiology and outcomes of infantile spasm epilepsy in Atlanta found that 83% of individuals under age 10 could develop mental disabilities, with 12% of 10-year-olds with profound mental disabilities having a history of infantile spasms. Describing epilepsy in terms of “behavioral phenotypes” within individual disability syndromes offers a promising method to explore epilepsy’s cause in cases with mental disabilities. Such categorization causes the correlation between genetic abnormalities and individual epilepsy, thereby guiding treatment options [25]. Soka et al. [26] showed that most epileptic patients with unknown causes had focal epilepsy and normal intelligence. Mental disability was diagnosed in 35% of patients and only 17% in this group was found with an unknown cause of epilepsy.

Analysis of EEG changes in epileptic patients showed that most of them (38.7%) had normal EEG, in contrast to 9.7% with focal slowing, 17.2% with diffuse slowing, 1.1% with epileptiform discharges and 3.2% with bilateral epileptiform discharges. The results showed that bilateral epileptiform discharge had a significant relationship with the age group. Also, both bilateral epileptiform discharge and focal slowness had a significant difference with marital status. The findings of other reports are consistent with ours. They showed that most epileptic patients had normal brain scans, which was significantly related to patients’ age, but did not show a significant relationship with gender [17, 27-29]. The clinical importance of EEG findings in cases with functional psychoses, especially whether such findings are state indicators or trait indicators, is not yet clear. Jasper et al. concluded that EEG findings in schizophrenia range from epileptic waves to strange “smooth” or “fluffy” lines. In patients with catatonic schizophrenia, Xinghua found similar EEG patterns of epileptic dysrhythmias and Walter found the same slow rhythms. Nonetheless, these EEG alterations were not studied as an indicator of schizophrenia status [30].

The current study revealed that the majority of patients (32.3%) had normal brain imaging, compared to 9.7% with cerebral cortical lesions, 8.6% with white matter lesions, 6.5% with cerebral atrophy, and 3.2% with hydrocephalus. The analysis of mean differences showed that the white matter lesions of the brain varied between men and women. Dehghani Firuzabadi et al. [31] found that CT brain imaging was abnormal in 35% and MRI in 50% of patients. Among those with generalized tonic-clonic seizures, 42.6% had abnormal brain imaging. Additionally, 76.9% of patients with other epilepsy types exhibited abnormal brain imaging. In the study by Afshari et al. [18], brain imaging was reported as “abnormal” in 15.8% of epileptic patients, with abnormalities including vascular lesions (6.6%), space-occupying lesions (2.5%), developmental cortex malformation (2.5%), and nonspecific lesions (2.5%). Most abnormalities were found in focal motor epilepsy. The highest rate of lesions was seen in patients with focal motor epilepsy, suggesting potential technical errors in CT scans or variances in the etiology of focal motor epilepsy across different populations.

Conclusion

Our findings showed that epilepsy with combined focal and generalized type and schizophrenia were the most common prevalent epilepsy and psychiatric disorders, respectively. Bipolar and related disorders exhibited significant gender differences. Additionally, developmental and personality disorders were significantly correlated with educational levels. Over half of the epileptic patients had an undetermined etiology, with no significant differences in etiology based on gender, age, marital status, education, and occupation. The majority of patients had normal EEGs, and their brain imaging predominantly showed normal findings, except for white matter lesions, which differed between men and women.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1400.072).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all participants in this project.

References

Epilepsy, a chronic disorder characterized by recurrent seizures, arises from the brain dysfunction due to excessive abnormal neuronal electrical discharges [1]. In 1870, scientists reported that seizures were caused by overcharging of nervous tissue in muscles [2]. Since ancient times, physicians have acknowledged the link between epilepsy and psychiatric disorders, although, in contemporary times, this relationship has been perceived as tenuous, with research in this domain remaining limited. However, the development of new antiepileptic and psychiatric drugs and new neuroimaging techniques makes it increasingly important to understand the relationship between epileptic seizures and the pathology of psychiatric disorders [3]. For a long period (in the modern world) epilepsy was considered a purely neurological disease involving the central nervous system, and physicians focused primarily on achieving a seizure-free state. Recent studies over the past decades have revealed that seizures represent just one aspect of epilepsy. Cognitive and psychiatric disorders are also prevalent among these patients, with one in three experiencing significant cognitive-psychiatric issues, which can sometimes overshadow convulsive symptoms in their clinical presentation [4].

Psychiatric conditions affect 32% to 41% of epileptic patients, often leading to a worse prognosis compared to those without psychiatric issues. Psychiatric disorders can emerge before, during, or after an epilepsy diagnosis, complicating treatment and diagnosis while worsening prognosis, increasing healthcare utilization, and imposing significant socioeconomic burdens globally due to chronic disability, dependence, and mortality. The strong correlation between psychiatric disorders and epilepsy highlights the necessity of investigating psychiatric disease risk factors and their temporal relationships in affected patients [5]. Some scholars argue that this connection does not imply that epilepsy causes psychiatric disorders or vice versa, but rather suggests a shared pathological pathway that culminates in both epilepsy and psychiatric conditions [6]. In most instances, psychiatric disorders manifest before the onset of epilepsy, negatively impacting the course of epilepsy and its future treatment, especially since epilepsy diagnosis is often delayed in these patients, leading to untimely treatment. Studies have shown that having a history of mood disorders before the onset of epilepsy can increase the risk of refractory epilepsy [7, 8]. Also, family or personal history of psychiatric disorders increases the likelihood of psychiatric side effects following the use of antiepileptic drugs [4, 9]. Studies also suggest that a history of anxiety and mood disorders may elevate the risk of seizures during stressful situations Furthermore, the quality of life (QoL) for epileptic patients declines if they suffer from psychiatric disorders, with the coexistence of mood disorders and anxiety in an epileptic patient being a strong predictor of a reduced QoL, imposing greater economic burdens on the patient, their family, and society [10, 11]. To gain insights into neurophysiological disorders, the electroencephalographic method is employed to differentiate neuropsychiatric patients from the healthy population [12]. Electroencephalography (EEG) allows for the recording and observation of brain electrical potentials stemming from the neural activity, known as an electroencephalogram. EEG signals reflect all mental and physical brain activities, enabling the recording of various brain activity patterns such as beta waves (12 to 30 Hz: High alertness), alpha (8 to 12 Hz: Wakefulness), theta (4 to 8 Hz: Fatigue), and delta (0.5 to 4 Hz: Low alertness) [13].

In previous studies, the rate of depression in the general population was 6 to 19%, and in epileptic patients 9 to 37%. The incidence of anxiety disorders in the general population has been reported 7-11% and in epileptic patients 11 to 25%. In a meta-analysis, the prevalence of psychosis in epileptic patients was estimated at 5.6%. Personality disorders also seem more prevalent in epileptic individuals compared to the general population, ranging from 6 to 14%, and in some studies, as high as 38% [8]. Epilepsy leads to poor academic performance, increases unemployment rates, and reduces patients’ incomes. Marriage and fertility rates are lower in epileptic patients, depriving them of a normal family and social life. Beyond the familial, social, and economic consequences of epilepsy, some studies have indicated that epilepsy is more likely to occur in individuals with low socioeconomic status, complicating psychiatric and cognitive issues [14, 15]. Therefore, epilepsy cannot be regarded solely as an organic disease affecting the central nervous system. The psychiatric dimensions are crucial in epileptic patients, influencing the treatment prognosis and the patients’ QoL on individual, familial, and societal levels. Although some studies have been conducted in this field in the last two decades, further studies are essential to uncover unknown aspects of this relationship and to underscore the importance of addressing psychiatric disorders in epileptic patients [4].

The prevalence of epilepsy in our country is higher than the global average due to the high rate of road accidents and survivors of the imposed war, but there is not enough information about the prevalence of cognitive and psychiatric disorders in these patients. Razi Psychiatric Center (Tehran, Iran), being one of the foremost facilities for treating and managing acute and chronic psychiatric patients, encounters individuals with seizures and epilepsy daily. This frequent occurrence can be linked to the scarcity of local clinical data on the coexistence of epilepsy and psychiatric disorders, coupled with inadequate awareness among physicians and the healthcare system regarding these conditions, complicating effective treatment for these patients. Therefore, conducting a comprehensive study to examine the various aspects of concurrent seizure-epilepsy and psychiatric disorders, utilizing EEG and brain imaging techniques at this center, stands as a significant step towards enhancing the mental health care of epilepsy patients. It will also improve treatment programs for these patients. Therefore, we investigated the clinical features, EEG, and brain imaging findings in psychiatric patients with epilepsy at Razi Psychiatric Hospital.

Materials and Methods

This descriptive retrospective study examined 94 files of epileptic patients with psychiatric disorders at Razi Psychiatric Hospital, affiliated with the Tehran University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, who were admitted between 2018 and 2020. Patients were diagnosed by clinical and physical examinations, EEG findings, and MRI imaging. The inclusion criteria were a) Patients with seizures confirmed by at least one neurologist based on clinical criteria, and b) Those with psychiatric illnesses confirmed by at least one psychiatrist based on clinical criteria. The exclusion criteria included: 1) Patients not assessed for a psychiatric disorder, 2) Patients diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder but not hospitalized, and 3) Patients lacking enough clinical, EEG or neuroimging data that could confirm seizure diagnosis. The information recorded in the files included age, sex, marital status, education, occupation, type of epilepsy, epilepsy etiology, EEG and brain imaging findings, the occurrence of epilepsy before psychiatric illness, and the use of antiepileptic drugs. Psychiatric disorders in this study included bipolar and related disorders, developmental disorder, anxiety, schizophrenia depressive, obsessive-compulsive, and related disorders, as well as substance and alcohol abuse disorder. Electroencephalogram changes examined were normal electroencephalogram, focal slowing, diffuse slowing, focal epileptiform discharges of focal attacks, and bilateral epileptiform discharges. Brain imaging changes studied included normal imaging, cerebral cortical lesions, white matter lesions, and cerebral atrophy. This information is recorded in HIS system of the hospital and were studied and data were collected by demographic checklist, epilepsy scale: The checklist used was made by DiIorio et al [16] and included personal characteristics, mental disorders, epilepsy and seizures. The Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney non-parametric tests were employed to compare the mean scores of variables and SPSS software, version 21 was used for data analysis.

Results

According to findings of present study, out of 94 epileptic patients, 64 were male (68.8%) and 30 were female (31.2%). Six individuals (6.5%) were under 18 years old, 81(87.1%) were aged between 18 and 60 years, and 7(6.5%) were over 60 years. Forty-one patients (44.1%) were single, 31(32.3%) were married, 19(20.4%) were divorced, and 3(3.2%) had a deceased spouse. Forty-four (47.3%) had education up to the 6th grade, 45(47.3%) had education between the 6th grade and diploma level, and 5(5.4%) had education beyond the diploma level. Also, 28 people (30.1%) were unemployed and 66 people (69.9%) were employed (Table 1).

The findings for epilepsy indicated that 9 patients (4.5%) had focal epilepsy, 24(12.0%) generalized epilepsy, 34(17.0%) focal and generalized epilepsy, and 26(13.0%) had epilepsy of unknown classification. The examination of psychiatric disorders revealed that 15 patients (16.1%) had developmental disorders, 52(55.9%) schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders, 32(34.4%) bipolar and related disorders, 21(22.6%) depressive disorder, 15(16.1%) anxiety disorder, 1(1.1%) obsessive-compulsive and related disorder, 31(33.3%) substance and alcohol abuse disorder, and 27(29.0%) had a personality disorder. The comparison between various psychiatric disorders showed significant differences in bipolar and related disorders between males and females (P<0.05). Developmental disorders across different age groups (P<0.01) also displayed a significant difference between married and single individuals. Additionally, developmental and personality disorders varied significantly among individuals with different educational levels (P<0.05) (Table 2).

The examination of etiology in 94 epileptic patients showed that 11 patients (10.8%) had a structural etiology, while the majority (n=83; 89.2%) had an unknown etiology. The comparison of means showed no significant differences in the etiology of patients regarding gender, age, marital status, education, and occupation (Table 3).

The results of EEG changes in epileptic patients showed that 36 patients (38.7%) had a normal electroencephalogram, 9 patients (9.7%) had focal slowing, 16 patients (17.2%) had diffuse slowing, 1 patient (1.1%) had focal epileptiform discharges and 3 patients (3.2%) had bilateral epileptiform discharges. The comparison of means indicated that the bilateral epileptiform discharges varied across different age groups. Focal slowness and bilateral epileptiform discharges exhibited a significant difference in relation to marital status (P<0.05; Table 4).

Brain imaging changes showed that 30 patients (32.3%) had normal brain imaging, 9 patients (9.7%) had cortical lesions, 8 patients (8.6%) had white matter lesions, 6 patients (6.5%) had cerebral atrophy, and 3 patients (3.2%) had hydrocephalus. The comparison of means revealed that white matter lesions in the brain differed between females and males (P<0.05) (Table 5).

Discussion

We investigated the clinical features, EEG findings, and brain imaging in psychiatric patients with epileptic disorders at Razi Psychiatric Hospital. The study found a higher prevalence of epilepsy among men compared to women. The majority of epileptic patients were aged between 18 and 60 years. Single epileptic individuals outnumbered married ones, with married patients being more numerous than those divorced, and divorced individuals exceeding those with deceased spouses. Most patients’ education levels ranged from elementary to diploma, and the majority were employed. In the study by Ghanbari Jolfaei et al. [17], the rate of being unmarried in patients with psychiatric disorders was higher compared to those married, aligning with our findings. However, the number of unemployed people was almost double that of the employed group, contrasting with our results. Also, the number of patients with elementary and diploma education was higher than those with higher education levels, consistent with our findings. The most common age range for epilepsy was between 21 to 53 years, presenting a narrower age range compared to our study. Afshari et al. [18] observed that most epileptic patients were women, differing from the results of our study, where most patients fell into the age group of 18 to 89 years. The analysis of different types of epilepsy showed that the highest frequency belonged to focal generalized epilepsy and the lowest was related to focal epilepsy, which is in line with the findings of Bahrainian et al. [19]. Our research indicated that the majority of epileptic patients were diagnosed with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, a finding consistent with previous studies exploring the epidemiological and etiological links between epilepsy and schizophrenia [19, 20]. The association between schizophrenia and epilepsy has been reported and studied by researchers for many years. Early psychiatrists like Kraepelin, who identified schizophrenia, associated it with epilepsy, while pioneers in epilepsy research like Gibbs noted an increased incidence of psychosis during the interictal phase in patients with focal epilepsy [20]. Li et al. [21] highlighted the association between epileptic disorders and schizophrenia. Adachi and Ito [22] showed a high incidence of epilepsy in schizophrenia patients (4 to 5 times higher than the general population). They found that patients with schizophrenia typically suffered from focal epilepsy and that a small number of patients with schizophrenia developed refractory epilepsy. Our study identified significant gender differences in bipolar and related disorders among psychiatric patients with epileptic disorders, Zhang et al. [23] found a close association between epilepsy and autism spectrum disorder, particularly in cases of early-onset epilepsy in women, and noted that the link between epilepsy and developmental disorders was more pronounced in younger individuals. We found a significant relationship between developmental disorder, and age, as well as marital status. Also, there was a significant association between developmental disorders and education and personality. Ghanbari Jolfaei et al. [17] found that the prevalence of psychiatric and behavioral disorders in epileptic patients is high and the type of epilepsy had no effect on the personality disorders.

The analysis of epilepsy’s etiology indicated that over half of the patients had unknown etiology and no significant difference was found between patients’ etiology and demographic factors, such as gender, age, marital status, education, and occupation. Bahrami et al. [24]reached similar findings, noting that a majority of epileptic patients had an unknown etiology, with an increase in frequency from ages 10 to 19, followed by a decrease. Nowadays, genetic advances have spread in identifying the individual causes of mental retardation and epilepsy. The genetic cause of epilepsy disorders is unclear, but certain rare epilepsy types have been linked to genetic disorders. Research into conditions such as infantile encephalopathy, infantile spasm, and myoclonic epilepsy, along with their treatment, suggests epilepsy may be associated with mental retardation. A study on the epidemiology and outcomes of infantile spasm epilepsy in Atlanta found that 83% of individuals under age 10 could develop mental disabilities, with 12% of 10-year-olds with profound mental disabilities having a history of infantile spasms. Describing epilepsy in terms of “behavioral phenotypes” within individual disability syndromes offers a promising method to explore epilepsy’s cause in cases with mental disabilities. Such categorization causes the correlation between genetic abnormalities and individual epilepsy, thereby guiding treatment options [25]. Soka et al. [26] showed that most epileptic patients with unknown causes had focal epilepsy and normal intelligence. Mental disability was diagnosed in 35% of patients and only 17% in this group was found with an unknown cause of epilepsy.

Analysis of EEG changes in epileptic patients showed that most of them (38.7%) had normal EEG, in contrast to 9.7% with focal slowing, 17.2% with diffuse slowing, 1.1% with epileptiform discharges and 3.2% with bilateral epileptiform discharges. The results showed that bilateral epileptiform discharge had a significant relationship with the age group. Also, both bilateral epileptiform discharge and focal slowness had a significant difference with marital status. The findings of other reports are consistent with ours. They showed that most epileptic patients had normal brain scans, which was significantly related to patients’ age, but did not show a significant relationship with gender [17, 27-29]. The clinical importance of EEG findings in cases with functional psychoses, especially whether such findings are state indicators or trait indicators, is not yet clear. Jasper et al. concluded that EEG findings in schizophrenia range from epileptic waves to strange “smooth” or “fluffy” lines. In patients with catatonic schizophrenia, Xinghua found similar EEG patterns of epileptic dysrhythmias and Walter found the same slow rhythms. Nonetheless, these EEG alterations were not studied as an indicator of schizophrenia status [30].

The current study revealed that the majority of patients (32.3%) had normal brain imaging, compared to 9.7% with cerebral cortical lesions, 8.6% with white matter lesions, 6.5% with cerebral atrophy, and 3.2% with hydrocephalus. The analysis of mean differences showed that the white matter lesions of the brain varied between men and women. Dehghani Firuzabadi et al. [31] found that CT brain imaging was abnormal in 35% and MRI in 50% of patients. Among those with generalized tonic-clonic seizures, 42.6% had abnormal brain imaging. Additionally, 76.9% of patients with other epilepsy types exhibited abnormal brain imaging. In the study by Afshari et al. [18], brain imaging was reported as “abnormal” in 15.8% of epileptic patients, with abnormalities including vascular lesions (6.6%), space-occupying lesions (2.5%), developmental cortex malformation (2.5%), and nonspecific lesions (2.5%). Most abnormalities were found in focal motor epilepsy. The highest rate of lesions was seen in patients with focal motor epilepsy, suggesting potential technical errors in CT scans or variances in the etiology of focal motor epilepsy across different populations.

Conclusion

Our findings showed that epilepsy with combined focal and generalized type and schizophrenia were the most common prevalent epilepsy and psychiatric disorders, respectively. Bipolar and related disorders exhibited significant gender differences. Additionally, developmental and personality disorders were significantly correlated with educational levels. Over half of the epileptic patients had an undetermined etiology, with no significant differences in etiology based on gender, age, marital status, education, and occupation. The majority of patients had normal EEGs, and their brain imaging predominantly showed normal findings, except for white matter lesions, which differed between men and women.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1400.072).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all participants in this project.

References

- Mufaddel A. Epilepsy and its Management in Relation to Psychiatry. International Journal of Neurorehabilitation (2014); 1(3):2376-81. [DOI: 10.4172/2376-0281.1000121]

- Ropper AH, Samuels MA, Klein JP. Adams & victor’s principles of neurology. New York: McGraw Hill LLC; 2019. [Link]

- Tolchin B, Hirsch LJ, LaFrance WC Jr. Neuropsychiatric Aspects of Epilepsy. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2020; 43(2):275-90. [DOIi: 10.1016/j.psc.2020.02.002] [PMID]

- Kanner AM. Psychiatric comorbidities in new onset epilepsy: Should they be always investigated? Seizure. 2017; 49:79-82. [DOI:10.1016/j.seizure.2017.04.007]

- Chang HJ, Liao CC, Hu CJ, Shen WW, Chen TL. Psychiatric disorders after epilepsy diagnosis: A population-based retrospective cohort study. Plos One. 2013; 8(4):e59999. [PMID]

- Kanner AM, Mazarati A, Koepp M. Biomarkers of epileptogenesis: Psychiatric comorbidities (?). Neurotherapeutics. 2014; 11(2):358-72. [DOI:10.1007/s13311-014-0271-4] [PMID]

- Petrovski S, Szoeke CE, Jones NC, Salzberg MR, Sheffield LJ, Huggins RM, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptomatology predicts seizure recurrence in newly treated patients. Neurology. 2010; 75(11):1015-21. [DOI:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f25b16] [PMID]

- Hitiris N, Mohanraj R, Norrie J, Sills GJ, Brodie MJ. Predictors of pharmacoresistant epilepsy. Epilepsy Research. 2007; 75(2-3):192-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2007.06.003] [PMID]

- Brent DA, Crumrine PK, Varma RR, Allan M, Allman C. Phenobarbital treatment and major depressive disorder in children with epilepsy. Pediatrics. 1987; 80(6):909-17. [PMID]

- Johnson EK, Jones JE, Seidenberg M, Hermann BP. The relative impact of anxiety, depression, and clinical seizure features on health-related quality of life in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2004; 45(5):544-50. [DOI:10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.47003.x] [PMID]

- Cramer JA, Blum D, Reed M, Fanning K; Epilepsy Impact Project Group. The influence of comorbid depression on quality of life for people with epilepsy. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2003; 4(5):515-21. [DOI:10.1016/j.yebeh.2003.07.009] [PMID]

- Thatcher RW. Neuropsychiatry and quantitative EEG in the 21 st century. Neuropsychiatry. 2011; 1(5):495-514. [Link]

- Shen KQ, Ong CJ, Li XP, Hui Z, Wilder-Smith EP. A feature selection method for multilevel mental fatigue EEG classification. IEEE Transactions on Bio-Medical Engineering. 2007; 54(7):1231-7. [DOI:10.1109/TBME.2007.890733] [PMID]

- Gilliam FG. Optimizing health outcomes in active epilepsy. Neurology. 2002; 58 (8_suppl_5) S9-S20. [DOI:10.1212/WNL.58.8_suppl_5.S9]

- Kanner AM, Barry JJ, Gilliam F, Hermann B, Meador KJ. Anxiety disorders, subsyndromic depressive episodes and major depressive episodes: Do they Differ on their impact on the quality of life of patients with epilepsy? Epilepsia. 2010; 51(7):1152-8. [DOI:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02582.x] [PMID]

- DiIorio C, Osborne Shafer P, Letz R, Henry T, Schomer DL, Yeager K, et al. The association of stigma with self-management and perceptions of health care among adults with epilepsy.” Epilepsy & Behavior. 2003; 4(3):259-67. [DOI:10.1016/S1525-5050(03)00103-3] [PMID]

- Ghanbari Jolfaei A, Nasr Esfahani M, Mirblock Jalali Z, Tamannai S. [Assessment of personality disorders in epileptic patients referred to epilepsy clinic of Rasoul Akram Hospital (Persian)]. Razi Journal of Medical Sciences 2015; 21(129):10-17. [Link]

- Afshari D, Rezaei M, Gilori E. CT scan findings of brain scan in epileptic patients referred to Kermanshah Neurology Clinic. Journal of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. 2012; 16(1):43-8. [Link]

- Bahrainian SA, Karamad A. [Investigation of anxiety in epileptic patients referred to the neurology clinic of Imam Hossein Hospital in Tehran and the Iranian Epilepsy Association (Persian)]. Journal of Research in Medicine. 2005; 29(3):235-8. [Link]

- Clancy MJ, Clarke MC, Connor DJ, Cannon M, Cotter DR. The prevalence of psychosis in epilepsy; a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2014; 14:75.[DOI:10.1186/1471-244X-14-75] [PMID]

- Li Q, Liu S, Guo M, Yang CX, Xu Y. The principles of electroconvulsive therapy based on correlations of schizophrenia and epilepsy: A view from brain networks. Frontiers in Neurology. 2019; 10:688. [DOI:10.3389/fneur.2019.00688] [PMID] ] [PMID]

- Adachi N, Ito M. Epilepsy in patients with schizophrenia: Pathophysiology and basic treatments. Epilepsy and Behavior. 2022; 127:108520. [DOI:10.1016/j.yebeh.2021.108520] [PMID]

- Zhang A, Li J, Zhang Y, Jin X, Ma J. Epilepsy and Autism spectrum disorder: An epidemiological study in Shanghai, China. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2019; 10:658. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00658] [PMID]

- Bahrami P, Farhadi A, Movahedi Y. [Frequency of seizure causes in patients referred to neurology clinic in Khorramabad city (Persian)]. Yafte. 2014; 16(2):24-31. [Link]

- Cascella NG, Schretlen DJ, Sawa A. Schizophrenia and epilepsy: Is there a shared susceptibility? Neuroscience Research. 2009; 63(4):227-235. [DOI:10.1016/j.neures.2009.01.002

- Sokka A, Olsen P, Kirjavainen J, Harju M, Keski-Nisula L, Räisänen S, et al. Etiology, syndrome diagnosis, and cognition in childhood-onset epilepsy: A population-based study. Epilepsia Open. 2017; 2(1):76-83. [DOI:10.1002/epi4.12036] [PMID]

- Bowley C, Kerr M. Epilepsy and intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2000; 44(5):529-43. [DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2788.2000.00270.x]

- Afsharkhas L, Kalbassi Z. [Electroencephalography in children with simple, complex, and recurrent febrile seizures (Persian)]. Razi Journal of Medical Sciences. 2015; 22(133):59-63. [Link]

- Hemmati M, Razazian N, Asadi Taha SA. [EEG disorder in patients with complex fever and seizures and related underlying factors (Persian)]. Journal of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences 2014; 18(5):298-302. [Link]

- Xinghua T, Lin L, Qinyi F, Yarong W, Zheng P, Zhenguo L. The clinical value of long - term electroencephalogram (EEG) in seizure - free populations: implications from a cross-sectional study. BMC Neurology. 2020; 20(1):88. [DOI:10.1186/s12883-019-1521-1] [PMID]

- Dehghani Firuzabadi M, Mohammadifard M, Mirgholami A, Sharifzadeh GR, Mohammadifard M. [MRI findings and clinical symptoms of patients with epilepsy referring to Valli-e-asr hospital between 2009 and 2010 (Persian)]. Journal of Birjand University of Medical Sciences. 2012; 19(4):422-9. [Link]

Article type: Original Research Articles |

Subject:

Neurorehabilitation

Received: 2022/10/3 | Accepted: 2023/11/25 | Published: 2024/03/16

Received: 2022/10/3 | Accepted: 2023/11/25 | Published: 2024/03/16

Send email to the article author