Volume 21, Issue 4 (December 2023)

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2023, 21(4): 721-730 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Karimi M, Barabadi H, Nesayan A, Abbassi H. The Effectiveness of Narrative Therapy on the Psychological Capital of Mothers of Children With Intellectual and Developmental Disability. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2023; 21 (4) :721-730

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1789-en.html

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1789-en.html

1- Department of Educational Sciences, Counselling, and Guidance, Faculty of Humanities, University of Bojnord, Bojnord, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities, University of Bojnord, Bojnord, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities, University of Bojnord, Bojnord, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 519 kb]

(3137 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3419 Views)

Full-Text: (1110 Views)

Introduction

Intellectual and developmental disability (IDD) is a type of disability that occurs before the age of 18 and is identified by an important limitation in both intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior, which includes many daily adaptive and social skills [1]. The prevalence of this disability is more than 1% in society [2]. The effects of having a child with IDD on the family are serious, so this disability in a child or children creates many emotional and economic disorders in the family in addition to threatening the mother-child relationship [3]. The birth of a child with a disability can bring feelings of worthlessness, guilt, or many psychological illnesses [4] such as depression [5], feelings of inadequacy, powerlessness, and experiences of negative emotions [6]. In such a situation, although all the members of the family and its function suffer due to their traditional role as caregivers, mothers take on more responsibilities towards their disabled children, resulting in more psychological problems [7]. It is hypothesized that problems related to caring for a troubled child put parents, especially mothers, at risk for mental health problems [8]. However, some studies show that these people have some positive psychological variables, they show that positive psychological variables can turn this challenge into an opportunity to empower parents, increase the capacity to accept a child with a disability and the feeling of inadequacy, reduce their discomfort, and ultimately improve their quality of life [9].

One of these variables is psychological capital, which ensures the mental health of these mothers by adjusting and diminishing the traumatic factors [10]. Psychological capital has shown a high capacity for adjustment and acceptance of disabled children as well as increasing family functioning in different life situations [11]. Psychological capital is a new concept introduced as positive human and social capital, consisting of four constructs: Hope, optimism, resilience, and self-efficacy. Each of them is regarded as a positive psychological capacity that can develop and significantly impact the interpersonal, social, and problem-solving behaviors of parents of IDD children and influence various aspects of cognitive, emotional function, and belief systems [12]. Research shows that psychological interventions have an effective role in controlling or reducing psychological symptoms or increasing mothers’ social and psychological abilities with IDD children. Interventions are designed based on parents’ narratives and for parents to help them reduce the effects of problems in their lives using the skills, beliefs, values, and abilities that parents have. Therefore, one of the new treatments that can reduce the problems of these mothers is narrative therapy [13].

In narrative therapy, human problems are viewed as issues that arise from agonizing stories affecting one’s life. The treatment process examines how people analyze their life stories by themselves, with the overall focus and emphasis being on creating new meanings in life [14]. According to this approach, the client’s biography is edited by the patient and the therapist, and the treatment serves as the biography editor. In other words, the therapist provides an active role for clients in treatment [15]. In this method, the individual learns to take responsibility for relieving and improving his or her psychological problems and practices it [16]. The treatment process examines how people analyze their life stories by themselves, and the primary focus and emphasis is on creating new meanings in life. Problems are like stories that people agree to tell themselves [17]. In narrative therapy, life can be found differently and from a new perspective. The rewriting of life is the ultimate goal of the narrative-therapeutic process [18].

Several studies have used the postmodern therapeutic approach, primarily narrative therapy. Carlson, and Epston [19], Greene [20], and Baldiwala and Kanakia [21] have emphasized the effect of narrative therapy on reducing psychological problems. Carlson and Epston, in a study titled “hope and narrative therapy,” showed that narrative therapy increases hope [19]. In another study entitled “narrative therapy for people with depression: Improving cognitive and emotional symptoms and consequences,” Seo et al. showed that narrative therapy reduces psychological and emotional problems associated with depression [22]. In a study to investigate the “effectiveness of group narrative therapy on the empowerment of female-headed households,” Eslami et al. also showed that narrative therapy is efficient in the empowerment of female-headed households [23].

Given what has been said, mothers of children with intellectual disabilities are under double pressure in the process of birth and raising their children. They tell themselves stories full of problems that seem to affect the components of their psychological capital (self-efficacy, optimism, hope, and resilience). Based on the previous studies, no research has investigated narrative therapy’s effectiveness in increasing mothers with IDD children’s psychological capital. Therefore, considering the existing research gaps, this study investigates the narrative therapy affects the psychological capital of mothers with IDD children.

Materials and Methods

This study was applied in terms of purpose using an experimental design (pre-test-post-test) with a control group for data collection. Narrative therapy was the independent variable, and psychological capital and its components were the dependent variables. The study’s statistical population included all mothers of children with intellectual disabilities in Aliabad Katoul City, Iran, in the academic year 2021-2022. Through available sampling, 30 volunteer members of the community who had a low score (score between 24 and 40) in the Luthans psychological capital questionnaire (2007) and had other inclusion criteria were randomly assigned to experimental and control groups (each group of 15 people).

Inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) The mother’s minimum age of 25 and the maximum age of 50, 2) The mother with primary education and higher, 3) A child with IDD, 4) A child with no other disability, 5) The healthy mother with no visual, hearing, and mental disorders. Also, exclusion criteria were: 1) Taking psychiatric drugs, 2) Simultaneously participating in another psychological intervention, 3) Being more than two sessions absent, and 4) Not wishing to continue cooperation.

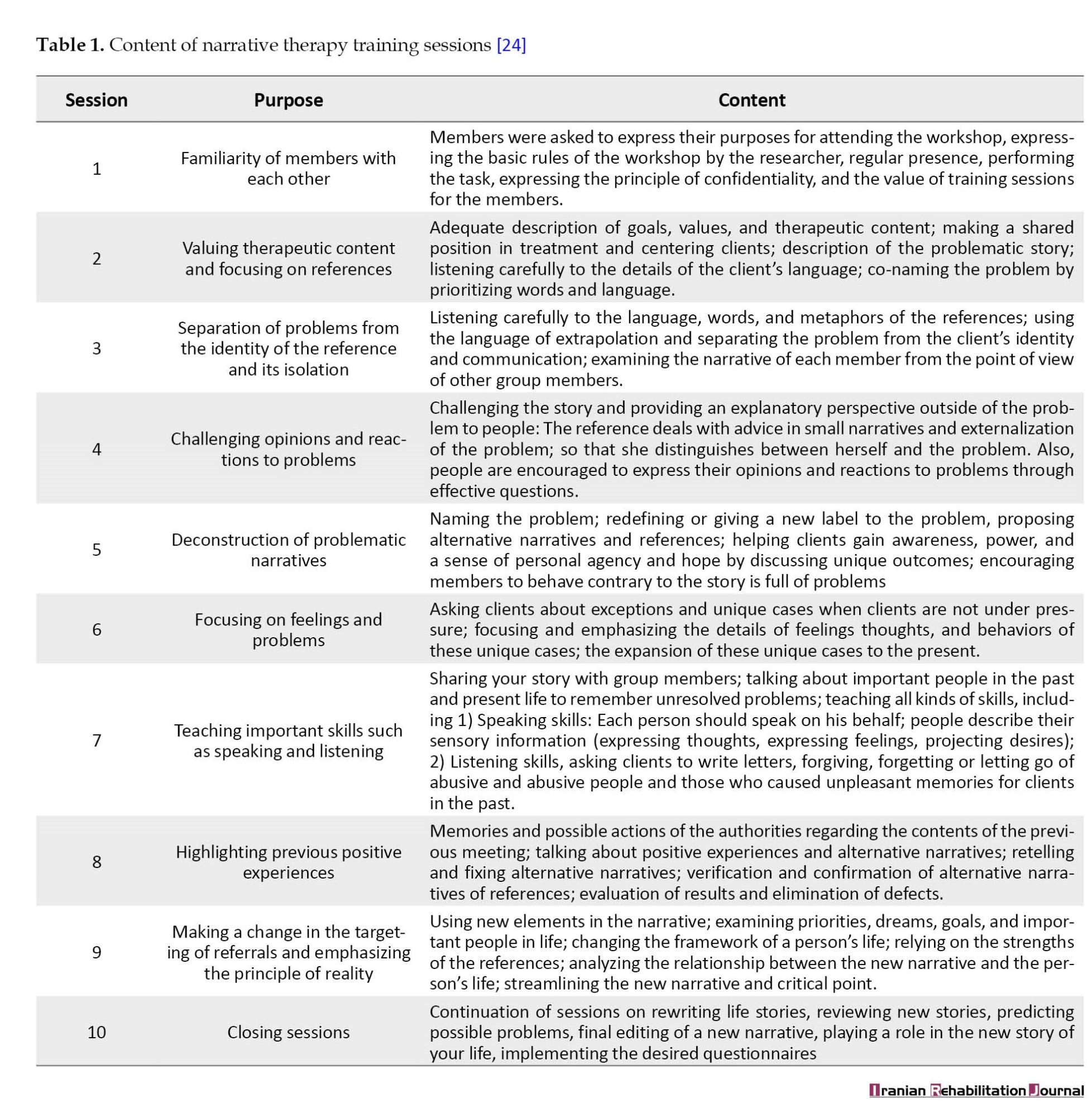

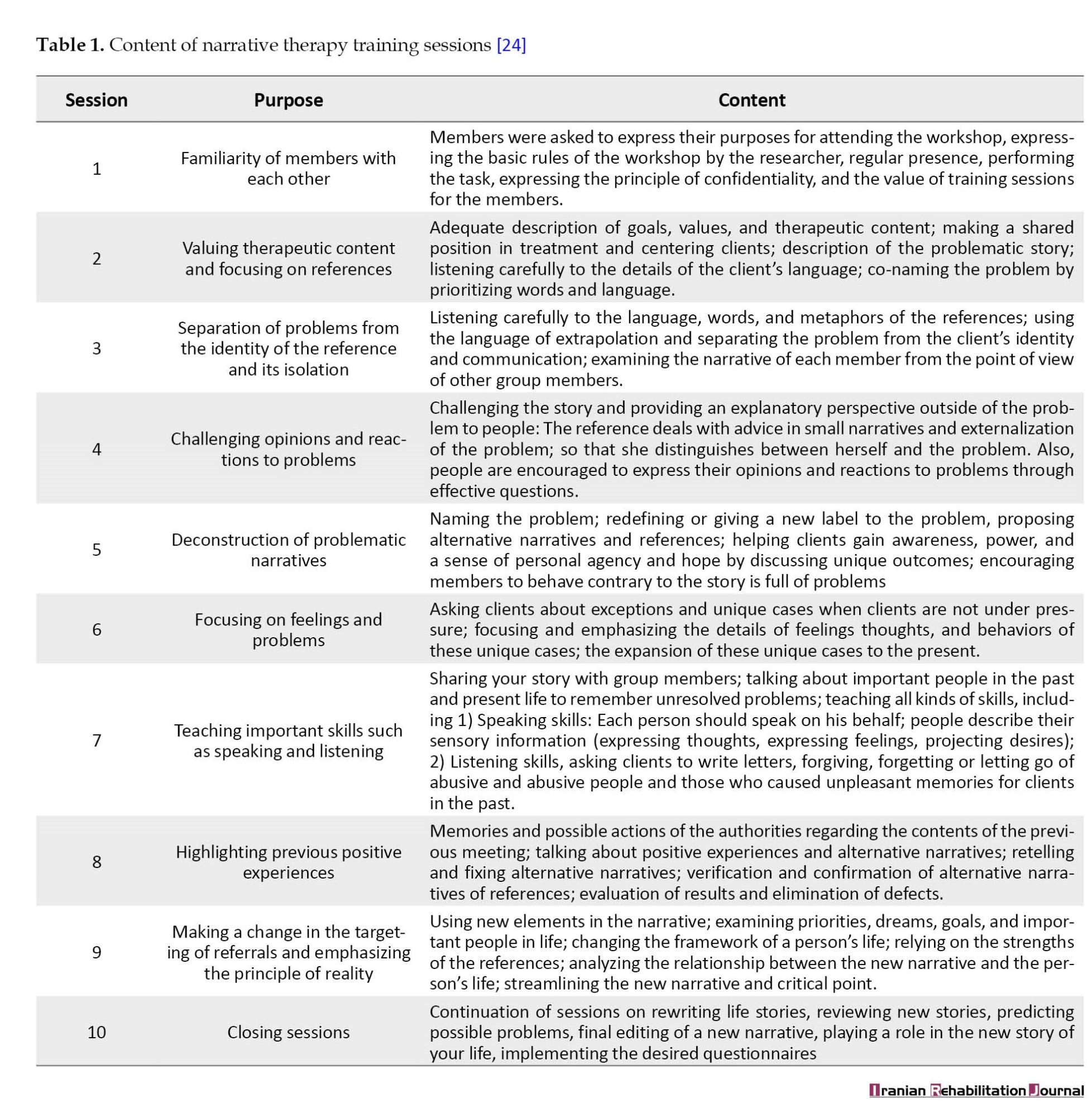

Before the intervention, the members of the experimental and control groups answered the Luthans psychological capital questionnaire in the form of a pre-test. After the necessary coordination, narrative therapy training sessions based on Lopez et al.’s treatment protocol [24] were held in 8 sessions of 50 minutes, twice a week, in groups, observing health protocols and maintaining social distancing to prevent the spread of the coronavirus.

Following the intervention, the participants in the experimental and control groups completed a post-test by responding to the questionnaire’s items. The outlines during the training sessions included:

This protocol is based on Lopez et al., studies of 2014, which was used by Jafari et al. [24] (Table 1).

Data were collected using the Luthans psychological capital questionnaire. The questionnaire consists of 24 questions; each subscale has 6 items. Subjects answered each item on a 6-point Likert scale from completely disagree (score 1), disagree (score 2), somewhat disagree (score 3), somewhat agree (score 4), agree (score 5), and completely agree (score 6). Each subscale is scored separately and then the total scores of the subscales are calculated as psychological capital.

According to Luthans, et al. psychological capital enhances the value of human capital, knowledge and skills of individuals, and social capital of the network of relationships between them in the organization [25]. This is because psychological capital relies on psychological variables of positivity like hope, optimism, resilience, and self-efficacy [26]. Luthans et al. believed that the relationship between the dimensions of this questionnaire and psychological capital is very high. They reported the Cronbach α for the subscales of hope, resilience, self-efficacy, and optimism, and the whole scale was 0.72, 0.71, 0.75, 0.74, and 0.88, respectively [25]. Also, based on Hashemi Nosratabad et al. using the Cronbach α method, the reliability of the questionnaire was obtained at 0.85 [27].

After collecting pre-test and post-test scores, the data were entered into SPSS software, version 22, and descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyze the data. Mean±SD were used to describe the score of psychological capital and its components in the pre-test and post-test. Analysis of covariance was used to test the research hypotheses.

Results

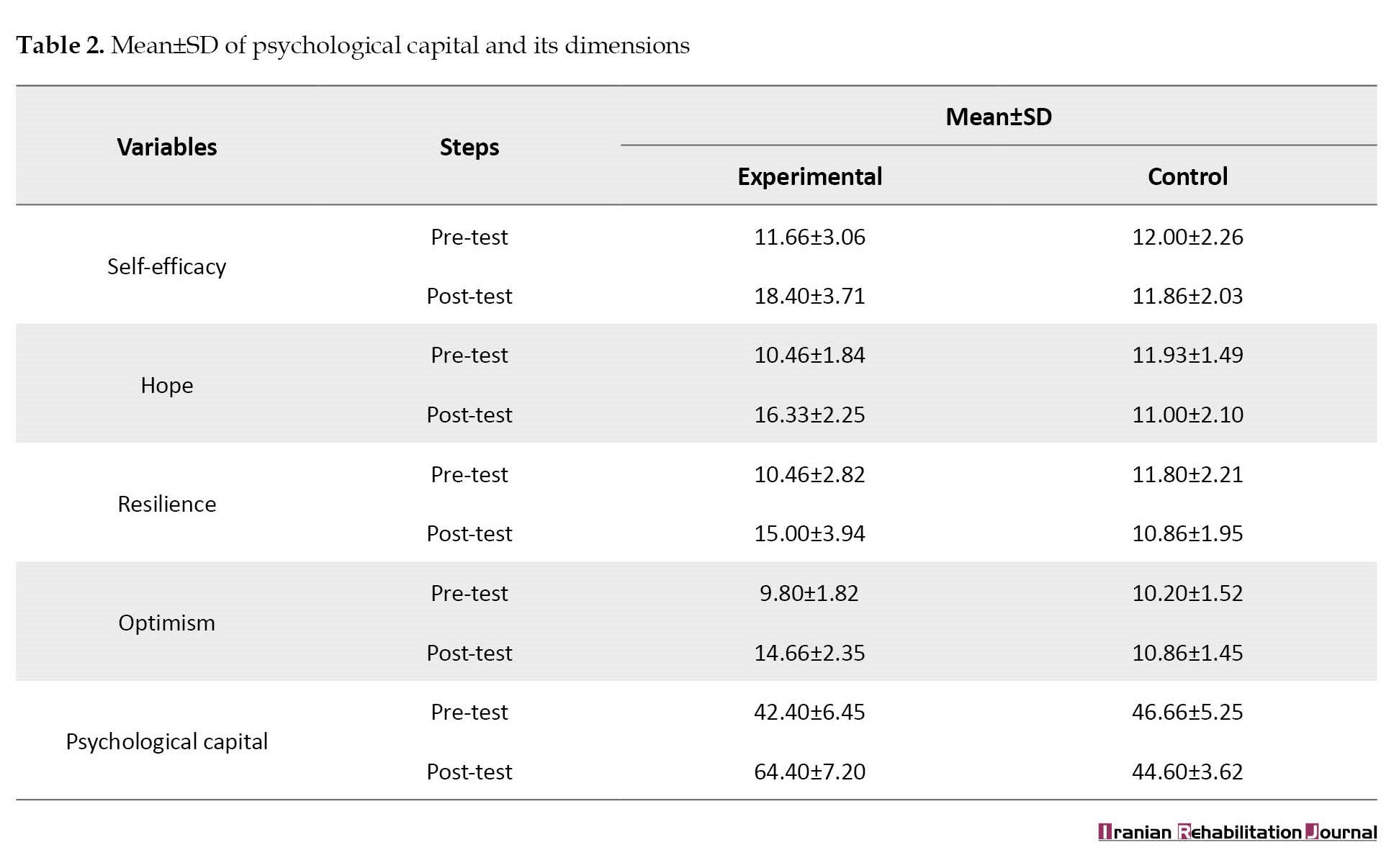

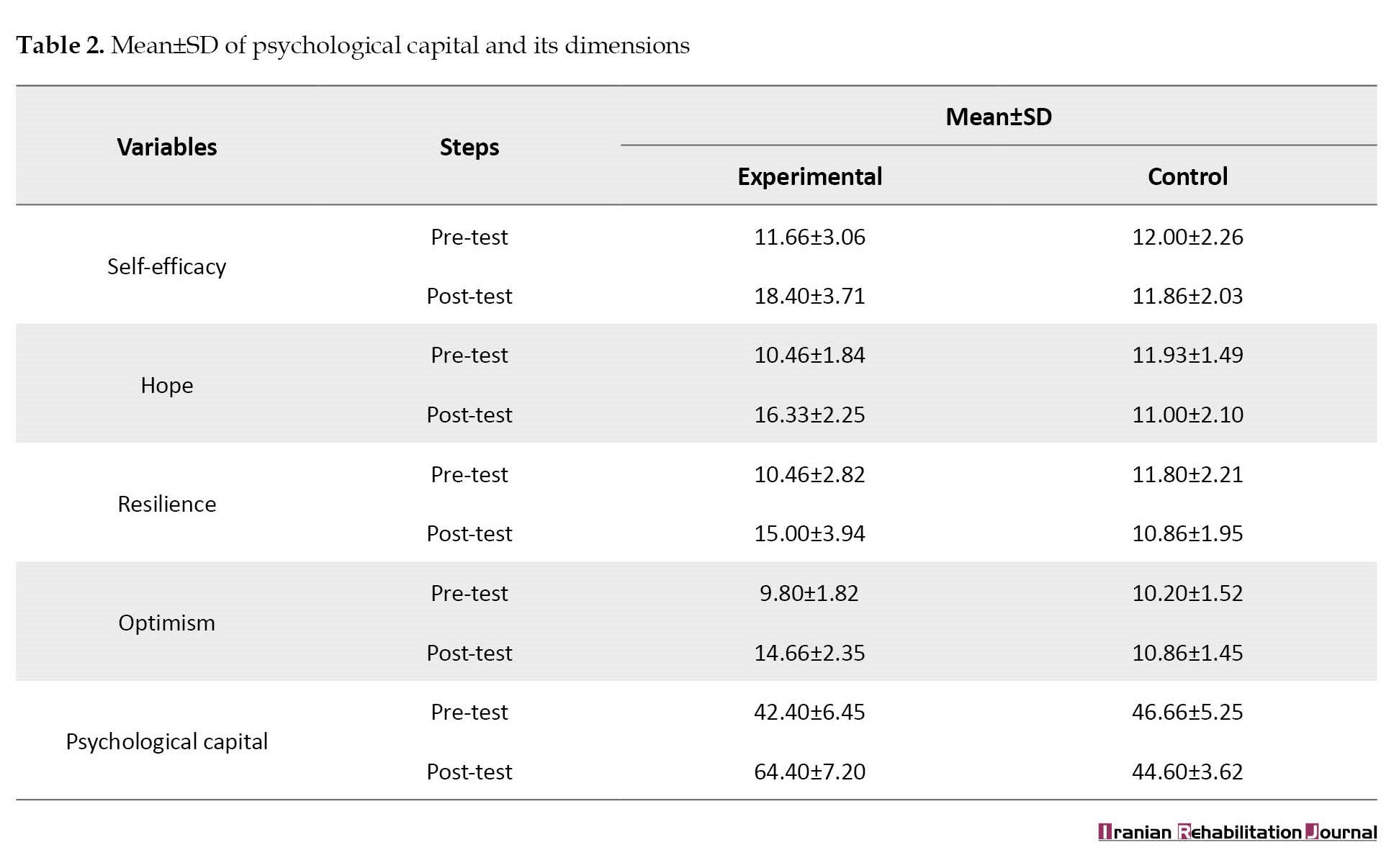

Based on demographic questions, 13 participants (43.33%) were in the age range of 20 and 25, 12(40%) were in the range of 26 to 30 years, and 5(16.67%) were in the range of 31 to 35 years. The Mean±SD participants’ ages ranged from 23 to 35 years old 26.6±3.70. In terms of education, 7(23.33%) had diplomas, 12(40%) had post-diplomas and bachelor’s degrees, 9(30%) had master’s degrees, and 2(6.7%) had doctoral degrees. The Mean±SD of the psychological capital variable and its dimensions are represented in Table 2 for the pre-test and post-test groups separately.

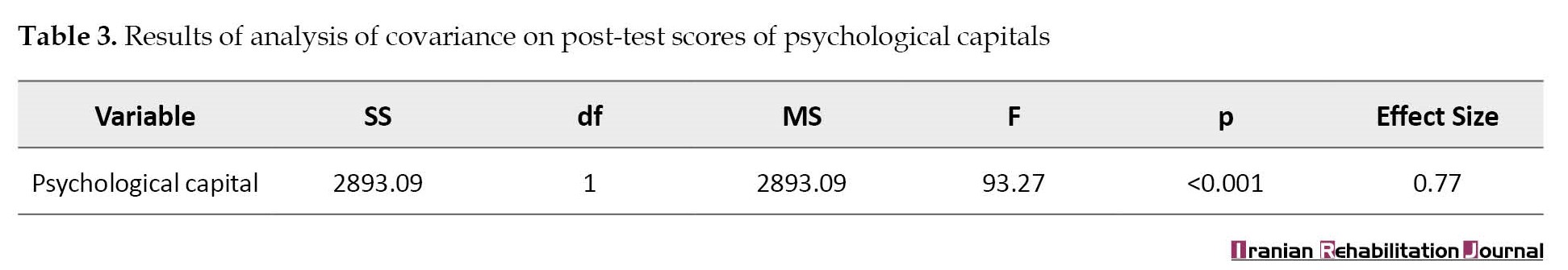

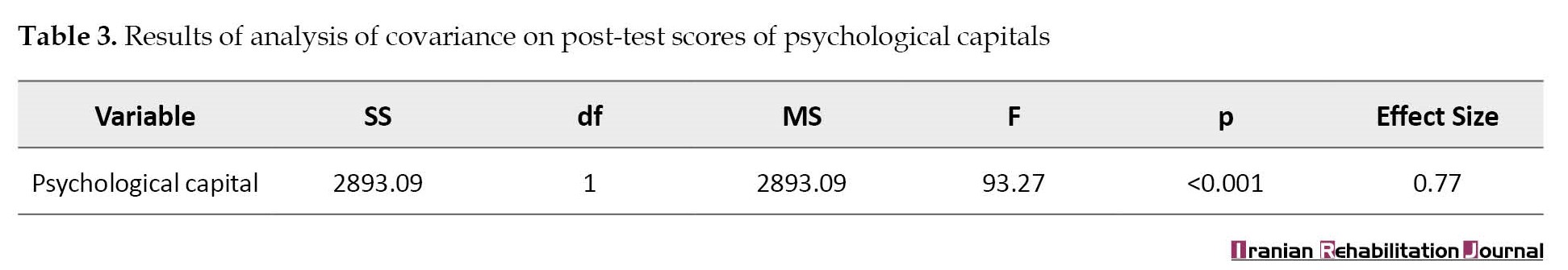

Examining the assumptions of covariance analysis showed that the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test values for the variable of psychological capital and its dimensions are not significant, P=0.05, and the distribution of these variables is normal. Levene’s test showed that the assumption of homogeneity of error variances for the variables of psychological capital, F=3.20, P≥0.05, self-efficacy, F=1.20, P=0.05, hope, F=0.83, P=0.05, resilience, F=3.82, P=0.05, and optimism, F=2.91, P=0.05, are established. Also, the assumption of homogeneity of the regression slopes for the variables of psychological capital, F=0.74, P=0.05, self-efficacy, F=2.28, P=0.05, hope, F=1.76, P=0.05, resilience, F=2.08, P=0.05, and optimism, F=0.69, P=0.05 was maintained. As a result, analysis of covariance was used to test the research hypotheses. Table 3 shows that by controlling the pre-test effect, there is a significant difference between the two experimental and control groups in terms of psychological capital variable, F=93.27, P<0.001.

Narrative therapy has been effective on the psychological capital of the participants in the experimental group compared to the control group. The effect of the intervention is 0.77. In other words, 0.77 changes in psychological capital are explained by narrative therapy.

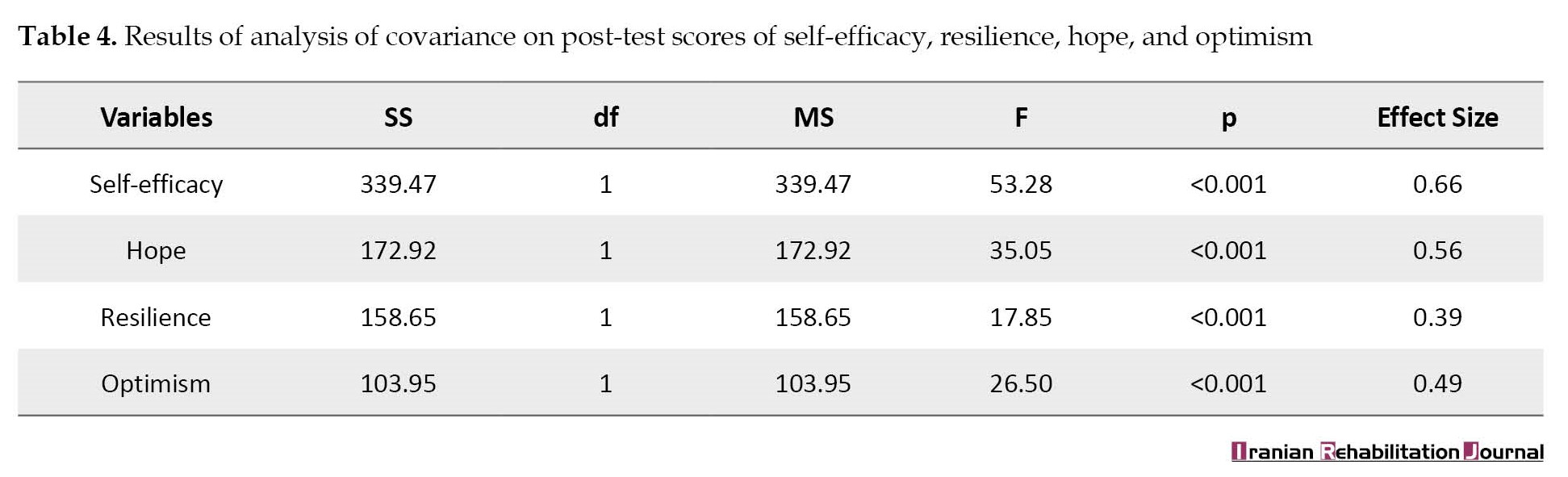

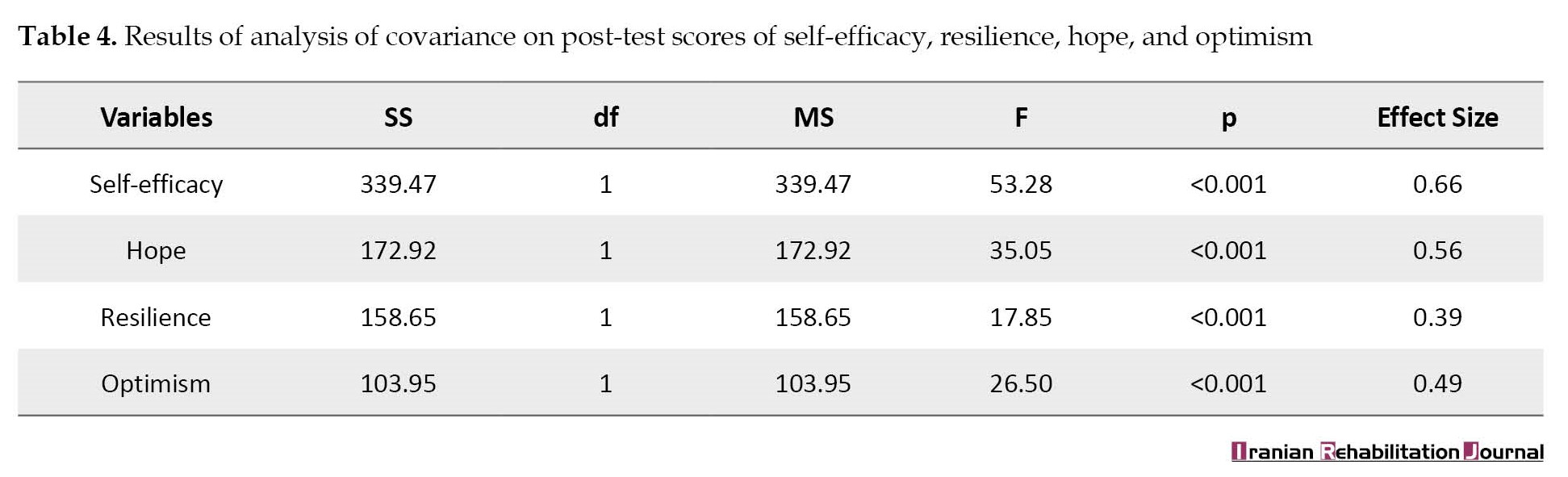

Pillai’s effect test showed that there is a significant difference between the two experimental and control groups in terms of at least one dependent variable (psychological capital dimensions), F=27.47, P<0.001. Therefore, to find out the differences between groups, univariate analysis of covariance was performed in the text of multivariate covariance analysis, the results of which are presented in Table 4.

Table 4 shows that after controlling the pre-test effect, there was a significant difference between the two experimental and control groups in terms of dimensions of self-efficacy, F=53.28, P<0.001, hope, F=35.05, P<0.001, resilience, F=17.85, P<0.001, and optimism, F=26.50, P<0.001. In other words, narrative therapy has been effective in the self-efficacy, hope, resilience, and optimism of the participants in the experimental group compared to the control group. The effect of the intervention for the above dimensions was 0.66, 0.56, 0.39, and 0.49, respectively.

Discussion

This study investigated the effectiveness of narrative therapy in increasing the psychological capital of mothers of children with IDD. The findings showed that narrative therapy increases the psychological capital of mothers of children with intellectual disabilities and its components.

Although no research was found directly assessing the effectiveness of narrative therapy on increasing the psychological capital of mothers of children with IDD, the results of this study are in line with some similar research. Our findings corroborate Fooladi et al.’s study on the effectiveness of group narrative therapy on the psychological well-being of mothers of children with hearing impairment [28]. It is also in line with Khodayari Fard and Sohrabpour’s results on the effectiveness of narrative therapy on the well-being and psychological helplessness of Iranian women [29]. Our results also align with Baldiwala and Kanakia’s study, titled “the use of narrative therapy in the treatment of disorders in families with children with developmental disorders: A qualitative study.” The study showed that narrative therapy plays an effective role in reducing psychological problems and increasing the quality of life and mental health [21].

To explain the results and the reasons for the effect of this approach on the psychological capital of mothers of IDD children, we can refer to the view that “the person is not the problem” in narrative therapy. This point of view in narrative therapy is a very useful and effective approach in paying attention to inefficient beliefs and correcting them, externalizing and disarming the problem, creating the ability to look at the problem from different angles, and finally creating a different interpretation and rewriting the life story [30].

Narrative therapy seems to have helped the resilience of mothers of IDD children by separating the individual from the problem, deconstructing uncompromising stories, and creating an atmosphere of choice. As Baldiwala and Kanakia have acknowledged, narrative therapy emphasizes the individual’s separation from his problem, making one realize that he or she can experience new things [21]. The “self” that was feeling inefficient due to mixing with the problem has become hopeful and feels efficient. This change from the “victim” role to an “agent” person creates flexible strategies. As Prochaska and Norcross have acknowledged, people using language in narrative therapy can become aware, understand, and accept their emotions with less impulsivity and more flexibility [31]. Consequently, the old and non-useful concepts woven into each other in the stories of one’s life are challenged in this method [21]. By expanding the view of references to themselves and discovering new information, new concepts are created. This information creates a suitable environment for positive changes in the client’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. When space and distance between the problem and the individual arise, the problem can be better investigated and the space of choice is formed. This space helps the individual to recognize what is constructive or counterproductive, which can lead to increased resilience. In this case, Caldwell says, talking about the problem does not mean talking about the individual, and the existential nature of the problem is not part of the inner truth of the individual [32]. In this situation, a space is made for the person to relax and use for searching or moving around to solve his problem. This is a space, in which a person, in collaboration with other people referred to as the narrative therapists, creates a new relationship between himself and the problem. This problem-solving move increases people’s resilience in the face of stressful situations. Given that language plays an important role in making experiences and semantics of events, the therapist used the language elements to create a different story in which mothers could overcome the problem.

Another reason is the impact of narrative therapy on the whole life and changing the overall narrative of the person instead of addressing one or more minor problems. Therefore, narrative therapy provides an opportunity for persons to review the roles they have set for themselves and others in the path of life. Attending psychotherapy sessions helps people to redefine problems in all areas as solvable by changing the dominant negative narrative through questioning, externalization, renaming, unique results, and finally rewriting and changing the life story to abilities. They hope to solve other life issues themselves. It seems that the mothers of IDD children gained a new perspective on themselves and realities in the treatment process which caused a reduction in unhealthy thoughts and attitudes towards themselves and the surrounding environment in different dimensions and made them pay attention to their abilities in a more realistic way. Adopting this new position made people feel self-efficacy to deal with problems and optimistically design a new narrative in which they hope to find new solutions instead of giving up.

The effect of narrative therapy on the psychological capital of mothers of IDD children can also be explained from the path of responsibility. Narrative therapy takes people from the position of passivity and helplessness to the position of choice and acceptance of responsibility and teaches people to look for new solutions and create their future [16]. The narrative therapist helps individuals to draw paths, narratives, different forms of life parts, opportunities, and possibilities in a broad way in their lives [20]. It teaches people that because they are responsible for creating and interpreting the stories of their lives, they must accept responsibility for their behavior [33]. Mothers of children with IDD accepted the responsibility of maintaining or changing the meaning of their life story by understanding this issue. Responsibility strengthens the sense of agency, self-efficacy, and resilience.

In narrative therapy, people can more easily adapt to current events through therapeutic conversations and telling their life stories [34]. A narrative therapist helps mothers chart the different paths, narratives, forms of life, opportunities, and possibilities in their lives. As Green pointed out, this interpretation leads to the fact that a person can achieve goals by relying on hope [20]. Clients’ dysfunctional beliefs about themselves, others, and the future seem to have changed as a result of narrative therapy. They no longer appear to view themselves as alone and miserable after participating in group sessions and hearing the stories of others who had experienced problems similar to their own. They heard narratives about how other people had overcome their problems and could see different perspectives for solving their challenges, as well as the feedback from the group’s members and the support they received from each other, widening the sparks of hope. Deconstruction and re-construction of narrative can affect the creation of a new path to achieve goals in creating hope in individual life. In addition, using the unique consequences technique, mothers found that they could move towards their goals and dreams in challenging situations and achieve success. These people had generally forgotten their accomplishments over time or had put them on the sidelines of their narratives. Examining the unique consequences of regaining those experiences had a significant impact on the restoration of those experiences, consequently increasing the sense of hope in the members.

The effectiveness of the narrative therapy approach on the psychological capital of mothers of mentally retarded children included implicit levels of clients’ experiences, externalizing the problem, having an enhanced sense of personal agency, and giving authority and responsibility to the people themselves. Collaborative and non-hierarchical work, intervention without blame, and moving from an intra-personal construction to a construction that is more interpersonal and relational is quite evident.

Restricting the scope of this study to mothers of children with intellectual disabilities, not having control over other variables affecting psychological capital, and not using a random sampling method were among the limitations of the present study. Therefore, to increase the generalizability of the results, it is suggested that this research be conducted in other contexts by controlling the variables affecting psychological capital and using a random sampling method. Given the effectiveness of this research in practice, it is recommended that family education instructors as well as therapists and counselors who work with mentally disabled children be introduced to group narrative therapy so they can take effective measures to improve the mental health and psychological capital of mothers of mentally disabled children.

Conclusion

The present study can contribute to the literature in the field of narrative therapy. The findings of this study show that there was a significant difference between the two experimental and control groups in terms of dimensions of self-efficacy, hope, resilience, and optimism. In general, the results showed that narrative therapy has effectively increased psychological capital and its dimensions (self-efficacy, resilience, hope, and optimism) in mothers with IDD children.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Ethical principles are considered in this research.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the master’s thesis of Mohammad Karimi, approved by Department of Educational Sciences, Counselling, and Guidance, Faculty of Humanities, University of Bojnord.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the director and deputies of Shahid Ali Akbar Goklani Exceptional School in Aliabad Katul and the mothers of the students who helped us in conducting the research.

References

Intellectual and developmental disability (IDD) is a type of disability that occurs before the age of 18 and is identified by an important limitation in both intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior, which includes many daily adaptive and social skills [1]. The prevalence of this disability is more than 1% in society [2]. The effects of having a child with IDD on the family are serious, so this disability in a child or children creates many emotional and economic disorders in the family in addition to threatening the mother-child relationship [3]. The birth of a child with a disability can bring feelings of worthlessness, guilt, or many psychological illnesses [4] such as depression [5], feelings of inadequacy, powerlessness, and experiences of negative emotions [6]. In such a situation, although all the members of the family and its function suffer due to their traditional role as caregivers, mothers take on more responsibilities towards their disabled children, resulting in more psychological problems [7]. It is hypothesized that problems related to caring for a troubled child put parents, especially mothers, at risk for mental health problems [8]. However, some studies show that these people have some positive psychological variables, they show that positive psychological variables can turn this challenge into an opportunity to empower parents, increase the capacity to accept a child with a disability and the feeling of inadequacy, reduce their discomfort, and ultimately improve their quality of life [9].

One of these variables is psychological capital, which ensures the mental health of these mothers by adjusting and diminishing the traumatic factors [10]. Psychological capital has shown a high capacity for adjustment and acceptance of disabled children as well as increasing family functioning in different life situations [11]. Psychological capital is a new concept introduced as positive human and social capital, consisting of four constructs: Hope, optimism, resilience, and self-efficacy. Each of them is regarded as a positive psychological capacity that can develop and significantly impact the interpersonal, social, and problem-solving behaviors of parents of IDD children and influence various aspects of cognitive, emotional function, and belief systems [12]. Research shows that psychological interventions have an effective role in controlling or reducing psychological symptoms or increasing mothers’ social and psychological abilities with IDD children. Interventions are designed based on parents’ narratives and for parents to help them reduce the effects of problems in their lives using the skills, beliefs, values, and abilities that parents have. Therefore, one of the new treatments that can reduce the problems of these mothers is narrative therapy [13].

In narrative therapy, human problems are viewed as issues that arise from agonizing stories affecting one’s life. The treatment process examines how people analyze their life stories by themselves, with the overall focus and emphasis being on creating new meanings in life [14]. According to this approach, the client’s biography is edited by the patient and the therapist, and the treatment serves as the biography editor. In other words, the therapist provides an active role for clients in treatment [15]. In this method, the individual learns to take responsibility for relieving and improving his or her psychological problems and practices it [16]. The treatment process examines how people analyze their life stories by themselves, and the primary focus and emphasis is on creating new meanings in life. Problems are like stories that people agree to tell themselves [17]. In narrative therapy, life can be found differently and from a new perspective. The rewriting of life is the ultimate goal of the narrative-therapeutic process [18].

Several studies have used the postmodern therapeutic approach, primarily narrative therapy. Carlson, and Epston [19], Greene [20], and Baldiwala and Kanakia [21] have emphasized the effect of narrative therapy on reducing psychological problems. Carlson and Epston, in a study titled “hope and narrative therapy,” showed that narrative therapy increases hope [19]. In another study entitled “narrative therapy for people with depression: Improving cognitive and emotional symptoms and consequences,” Seo et al. showed that narrative therapy reduces psychological and emotional problems associated with depression [22]. In a study to investigate the “effectiveness of group narrative therapy on the empowerment of female-headed households,” Eslami et al. also showed that narrative therapy is efficient in the empowerment of female-headed households [23].

Given what has been said, mothers of children with intellectual disabilities are under double pressure in the process of birth and raising their children. They tell themselves stories full of problems that seem to affect the components of their psychological capital (self-efficacy, optimism, hope, and resilience). Based on the previous studies, no research has investigated narrative therapy’s effectiveness in increasing mothers with IDD children’s psychological capital. Therefore, considering the existing research gaps, this study investigates the narrative therapy affects the psychological capital of mothers with IDD children.

Materials and Methods

This study was applied in terms of purpose using an experimental design (pre-test-post-test) with a control group for data collection. Narrative therapy was the independent variable, and psychological capital and its components were the dependent variables. The study’s statistical population included all mothers of children with intellectual disabilities in Aliabad Katoul City, Iran, in the academic year 2021-2022. Through available sampling, 30 volunteer members of the community who had a low score (score between 24 and 40) in the Luthans psychological capital questionnaire (2007) and had other inclusion criteria were randomly assigned to experimental and control groups (each group of 15 people).

Inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) The mother’s minimum age of 25 and the maximum age of 50, 2) The mother with primary education and higher, 3) A child with IDD, 4) A child with no other disability, 5) The healthy mother with no visual, hearing, and mental disorders. Also, exclusion criteria were: 1) Taking psychiatric drugs, 2) Simultaneously participating in another psychological intervention, 3) Being more than two sessions absent, and 4) Not wishing to continue cooperation.

Before the intervention, the members of the experimental and control groups answered the Luthans psychological capital questionnaire in the form of a pre-test. After the necessary coordination, narrative therapy training sessions based on Lopez et al.’s treatment protocol [24] were held in 8 sessions of 50 minutes, twice a week, in groups, observing health protocols and maintaining social distancing to prevent the spread of the coronavirus.

Following the intervention, the participants in the experimental and control groups completed a post-test by responding to the questionnaire’s items. The outlines during the training sessions included:

This protocol is based on Lopez et al., studies of 2014, which was used by Jafari et al. [24] (Table 1).

Data were collected using the Luthans psychological capital questionnaire. The questionnaire consists of 24 questions; each subscale has 6 items. Subjects answered each item on a 6-point Likert scale from completely disagree (score 1), disagree (score 2), somewhat disagree (score 3), somewhat agree (score 4), agree (score 5), and completely agree (score 6). Each subscale is scored separately and then the total scores of the subscales are calculated as psychological capital.

According to Luthans, et al. psychological capital enhances the value of human capital, knowledge and skills of individuals, and social capital of the network of relationships between them in the organization [25]. This is because psychological capital relies on psychological variables of positivity like hope, optimism, resilience, and self-efficacy [26]. Luthans et al. believed that the relationship between the dimensions of this questionnaire and psychological capital is very high. They reported the Cronbach α for the subscales of hope, resilience, self-efficacy, and optimism, and the whole scale was 0.72, 0.71, 0.75, 0.74, and 0.88, respectively [25]. Also, based on Hashemi Nosratabad et al. using the Cronbach α method, the reliability of the questionnaire was obtained at 0.85 [27].

After collecting pre-test and post-test scores, the data were entered into SPSS software, version 22, and descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyze the data. Mean±SD were used to describe the score of psychological capital and its components in the pre-test and post-test. Analysis of covariance was used to test the research hypotheses.

Results

Based on demographic questions, 13 participants (43.33%) were in the age range of 20 and 25, 12(40%) were in the range of 26 to 30 years, and 5(16.67%) were in the range of 31 to 35 years. The Mean±SD participants’ ages ranged from 23 to 35 years old 26.6±3.70. In terms of education, 7(23.33%) had diplomas, 12(40%) had post-diplomas and bachelor’s degrees, 9(30%) had master’s degrees, and 2(6.7%) had doctoral degrees. The Mean±SD of the psychological capital variable and its dimensions are represented in Table 2 for the pre-test and post-test groups separately.

Examining the assumptions of covariance analysis showed that the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test values for the variable of psychological capital and its dimensions are not significant, P=0.05, and the distribution of these variables is normal. Levene’s test showed that the assumption of homogeneity of error variances for the variables of psychological capital, F=3.20, P≥0.05, self-efficacy, F=1.20, P=0.05, hope, F=0.83, P=0.05, resilience, F=3.82, P=0.05, and optimism, F=2.91, P=0.05, are established. Also, the assumption of homogeneity of the regression slopes for the variables of psychological capital, F=0.74, P=0.05, self-efficacy, F=2.28, P=0.05, hope, F=1.76, P=0.05, resilience, F=2.08, P=0.05, and optimism, F=0.69, P=0.05 was maintained. As a result, analysis of covariance was used to test the research hypotheses. Table 3 shows that by controlling the pre-test effect, there is a significant difference between the two experimental and control groups in terms of psychological capital variable, F=93.27, P<0.001.

Narrative therapy has been effective on the psychological capital of the participants in the experimental group compared to the control group. The effect of the intervention is 0.77. In other words, 0.77 changes in psychological capital are explained by narrative therapy.

Pillai’s effect test showed that there is a significant difference between the two experimental and control groups in terms of at least one dependent variable (psychological capital dimensions), F=27.47, P<0.001. Therefore, to find out the differences between groups, univariate analysis of covariance was performed in the text of multivariate covariance analysis, the results of which are presented in Table 4.

Table 4 shows that after controlling the pre-test effect, there was a significant difference between the two experimental and control groups in terms of dimensions of self-efficacy, F=53.28, P<0.001, hope, F=35.05, P<0.001, resilience, F=17.85, P<0.001, and optimism, F=26.50, P<0.001. In other words, narrative therapy has been effective in the self-efficacy, hope, resilience, and optimism of the participants in the experimental group compared to the control group. The effect of the intervention for the above dimensions was 0.66, 0.56, 0.39, and 0.49, respectively.

Discussion

This study investigated the effectiveness of narrative therapy in increasing the psychological capital of mothers of children with IDD. The findings showed that narrative therapy increases the psychological capital of mothers of children with intellectual disabilities and its components.

Although no research was found directly assessing the effectiveness of narrative therapy on increasing the psychological capital of mothers of children with IDD, the results of this study are in line with some similar research. Our findings corroborate Fooladi et al.’s study on the effectiveness of group narrative therapy on the psychological well-being of mothers of children with hearing impairment [28]. It is also in line with Khodayari Fard and Sohrabpour’s results on the effectiveness of narrative therapy on the well-being and psychological helplessness of Iranian women [29]. Our results also align with Baldiwala and Kanakia’s study, titled “the use of narrative therapy in the treatment of disorders in families with children with developmental disorders: A qualitative study.” The study showed that narrative therapy plays an effective role in reducing psychological problems and increasing the quality of life and mental health [21].

To explain the results and the reasons for the effect of this approach on the psychological capital of mothers of IDD children, we can refer to the view that “the person is not the problem” in narrative therapy. This point of view in narrative therapy is a very useful and effective approach in paying attention to inefficient beliefs and correcting them, externalizing and disarming the problem, creating the ability to look at the problem from different angles, and finally creating a different interpretation and rewriting the life story [30].

Narrative therapy seems to have helped the resilience of mothers of IDD children by separating the individual from the problem, deconstructing uncompromising stories, and creating an atmosphere of choice. As Baldiwala and Kanakia have acknowledged, narrative therapy emphasizes the individual’s separation from his problem, making one realize that he or she can experience new things [21]. The “self” that was feeling inefficient due to mixing with the problem has become hopeful and feels efficient. This change from the “victim” role to an “agent” person creates flexible strategies. As Prochaska and Norcross have acknowledged, people using language in narrative therapy can become aware, understand, and accept their emotions with less impulsivity and more flexibility [31]. Consequently, the old and non-useful concepts woven into each other in the stories of one’s life are challenged in this method [21]. By expanding the view of references to themselves and discovering new information, new concepts are created. This information creates a suitable environment for positive changes in the client’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. When space and distance between the problem and the individual arise, the problem can be better investigated and the space of choice is formed. This space helps the individual to recognize what is constructive or counterproductive, which can lead to increased resilience. In this case, Caldwell says, talking about the problem does not mean talking about the individual, and the existential nature of the problem is not part of the inner truth of the individual [32]. In this situation, a space is made for the person to relax and use for searching or moving around to solve his problem. This is a space, in which a person, in collaboration with other people referred to as the narrative therapists, creates a new relationship between himself and the problem. This problem-solving move increases people’s resilience in the face of stressful situations. Given that language plays an important role in making experiences and semantics of events, the therapist used the language elements to create a different story in which mothers could overcome the problem.

Another reason is the impact of narrative therapy on the whole life and changing the overall narrative of the person instead of addressing one or more minor problems. Therefore, narrative therapy provides an opportunity for persons to review the roles they have set for themselves and others in the path of life. Attending psychotherapy sessions helps people to redefine problems in all areas as solvable by changing the dominant negative narrative through questioning, externalization, renaming, unique results, and finally rewriting and changing the life story to abilities. They hope to solve other life issues themselves. It seems that the mothers of IDD children gained a new perspective on themselves and realities in the treatment process which caused a reduction in unhealthy thoughts and attitudes towards themselves and the surrounding environment in different dimensions and made them pay attention to their abilities in a more realistic way. Adopting this new position made people feel self-efficacy to deal with problems and optimistically design a new narrative in which they hope to find new solutions instead of giving up.

The effect of narrative therapy on the psychological capital of mothers of IDD children can also be explained from the path of responsibility. Narrative therapy takes people from the position of passivity and helplessness to the position of choice and acceptance of responsibility and teaches people to look for new solutions and create their future [16]. The narrative therapist helps individuals to draw paths, narratives, different forms of life parts, opportunities, and possibilities in a broad way in their lives [20]. It teaches people that because they are responsible for creating and interpreting the stories of their lives, they must accept responsibility for their behavior [33]. Mothers of children with IDD accepted the responsibility of maintaining or changing the meaning of their life story by understanding this issue. Responsibility strengthens the sense of agency, self-efficacy, and resilience.

In narrative therapy, people can more easily adapt to current events through therapeutic conversations and telling their life stories [34]. A narrative therapist helps mothers chart the different paths, narratives, forms of life, opportunities, and possibilities in their lives. As Green pointed out, this interpretation leads to the fact that a person can achieve goals by relying on hope [20]. Clients’ dysfunctional beliefs about themselves, others, and the future seem to have changed as a result of narrative therapy. They no longer appear to view themselves as alone and miserable after participating in group sessions and hearing the stories of others who had experienced problems similar to their own. They heard narratives about how other people had overcome their problems and could see different perspectives for solving their challenges, as well as the feedback from the group’s members and the support they received from each other, widening the sparks of hope. Deconstruction and re-construction of narrative can affect the creation of a new path to achieve goals in creating hope in individual life. In addition, using the unique consequences technique, mothers found that they could move towards their goals and dreams in challenging situations and achieve success. These people had generally forgotten their accomplishments over time or had put them on the sidelines of their narratives. Examining the unique consequences of regaining those experiences had a significant impact on the restoration of those experiences, consequently increasing the sense of hope in the members.

The effectiveness of the narrative therapy approach on the psychological capital of mothers of mentally retarded children included implicit levels of clients’ experiences, externalizing the problem, having an enhanced sense of personal agency, and giving authority and responsibility to the people themselves. Collaborative and non-hierarchical work, intervention without blame, and moving from an intra-personal construction to a construction that is more interpersonal and relational is quite evident.

Restricting the scope of this study to mothers of children with intellectual disabilities, not having control over other variables affecting psychological capital, and not using a random sampling method were among the limitations of the present study. Therefore, to increase the generalizability of the results, it is suggested that this research be conducted in other contexts by controlling the variables affecting psychological capital and using a random sampling method. Given the effectiveness of this research in practice, it is recommended that family education instructors as well as therapists and counselors who work with mentally disabled children be introduced to group narrative therapy so they can take effective measures to improve the mental health and psychological capital of mothers of mentally disabled children.

Conclusion

The present study can contribute to the literature in the field of narrative therapy. The findings of this study show that there was a significant difference between the two experimental and control groups in terms of dimensions of self-efficacy, hope, resilience, and optimism. In general, the results showed that narrative therapy has effectively increased psychological capital and its dimensions (self-efficacy, resilience, hope, and optimism) in mothers with IDD children.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Ethical principles are considered in this research.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the master’s thesis of Mohammad Karimi, approved by Department of Educational Sciences, Counselling, and Guidance, Faculty of Humanities, University of Bojnord.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the director and deputies of Shahid Ali Akbar Goklani Exceptional School in Aliabad Katul and the mothers of the students who helped us in conducting the research.

References

- Kirk S, Gallagher JJ, Coleman MR. Educating exceptional children. Boston: Cengage Learning; 2014. [Link]

- Ganji M. Psychology of exceptional children. Tehran: Savalan; 2020. [Link]

- Farahani M, Hamidi Pour, Heidari H. [Effectiveness of native solution-focused therapy based on narrations of mothers with mentally retarded children on their resilience (Persian)]. Journal of Behavioral Sciences Research. 2021; 18(4):503-9. [DOI:10.52547/rbs.18.4.503]

- You C, Xu N, Qiu S, Li Y, Xu L, Li X, et al. A novel composition of two heterozygous GFM1 mutations in a Chinese child with epilepsy and mental retardation. Brain and Behavior. 2020; 10(10):e01791. [DOI:10.1002/brb3.1791] [PMID]

- Prieto M, Folci A, Martin S. Post-translational modifications of the Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein in neuronal function and dysfunction. Molecular Psychiatry. 2020; 25(8):1688-703. [DOI:10.1038/s41380-019-0629-4] [PMID]

- Hoyle JN, Laditka JN, Laditka SB. Mental health risks of parents of children with developmental disabilities: A nationally representative study in the United States. Disability and Health Journal. 2021; 14(2):101020. [DOI:10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.101020] [PMID]

- Alidoosti F, Jangi F, Shojaeifar S. [The effectiveness of emotion regulation training based on Gross Model on emotion regulation, anxiety and depression in mothers of children with intellectual disability (Persian)]. Journal of Family Psychology. 2020; 7(1):69-80. [DOI:10.52547/ijfp.7.1.69]

- Villavicencio CE, López-Larrosa S. Ecuadorian mothers of preschool children with and without intellectual disabilities: Individual and family dimensions. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2020; 105:103735. [DOI:10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103735] [PMID]

- Heifetz M, Brown HK, Chacra MA, Tint A, Vigod S, Bluestein D, et al. Mental health challenges and resilience among mothers with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Disability and Health Journal. 2019; 12(4):602-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.dhjo.2019.06.006] [PMID]

- Aghaei S, Yousefi Z. The effectiveness of quality of life therapy on psychological capitals and its dimensions among mothers of children with intellectual disability. Journal of Child Mental Health. 2017; 4(2):49-59. [Link]

- Hematihajiprirlu Sh, HeidarNikkho Gh. [Comparison of psychological capital of social capital, mental health and health literacy among mothers of mentally disabled children and mothers of normal children (Persian)]. Paper presented at: The 1st International Conference on New Research in The Field of Educational Sciences, Psychology and Social Studies of Iran. 14 June 2016, Qom, Iran. [Link]

- Fang SH, Ding D. The efficacy of group-based acceptance and commitment therapy on psychological capital and school engagement: A pilot study among Chinese adolescents. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 2020; 16:134-43. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.04.005]

- Lucas CV, Soares L, Oliveira F. Asperger syndrome and adolescent girl: Understanding the rhythm of emotions towards the struggle with social relationships-cognitive-behavioral and narrative therapy. In: Papaneophytou NL, Das UN, editors. Emerging programs for Autism Spectrum disorder: Improving communication, behavior, and family dynamics. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2021. [DOI:10.1016/B978-0-323-85031-5.00011-6]

- Ortigo KM, Bauer A, Cloitre M. Skills training in affective and interpersonal regulation (stair) narrative therapy: Making meaning while learning skills. In: Tull MT, Kimbrel NA, editors. Emotion in Posttraumatic Stress disorder: Etiology, assessment, neurobiology, and treatment. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2020. [DOI:10.1016/B978-0-12-816022-0.00018-1]

- Povea H. Narrative therapy for managing sexual dysfunctions in adults associated to childhood sexual abuse. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2017; 14(Supplement_4b):e339. [DOI:10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.04.600]

- Changizi F, Panahali Amir. [Effectiveness of group narrative therapy on life expectancy and happiness of the elderly in Tabriz (Persian)]. Journal of Education and Evaluation. 2016; 9(34):63-76. [Link]

- Wright A, Reisig A, Cullen B. Efficacy and cultural adaptations of narrative exposure therapy for trauma-related outcomes in refugees/asylum-seekers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy. 2020; 30(4):301-14. [DOI:10.1016/j.jbct.2020.10.003]

- Choob Foroush Zadeh A, Saied Manesh M, Rashidi MS. [Effectiveness of narrative therapy group on the cognitive flexibility of headless adolescents girls in welfare centers of Mashhad (Persian)]. Middle Eastern Journal of Disability Studies. 2018; 8:76. [Link]

- Epston D, Carlson TS. Insider witnessing practice: Performing hope and beauty in narrative therapy: Part two. Journal of Narrative Family Therapy. 2017; 19-38. [Link]

- Greene BC. A preliminary program evaluation of a narrative therapy intervention for persons incarcerated for violent crime [PhD Dissertation]. New York: City University of New York (CUNY); 2018. [Link]

- Baldiwala J, Kanakia T. Using narrative therapy with children experiencing developmental disabilities and their families in India: A qualitative study. Journal of Child Health Care. 2022; 26(2):307-18. [DOI:10.1177/13674935211014739] [PMID]

- Seo M, Kang HS, Lee YJ, Chae SM. Narrative therapy with an emotional approach for people with depression: Improved symptom and cognitive-emotional outcomes. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2015; 22(6):379-89. [DOI:10.1111/jpm.12200] [PMID]

- Eslami N, Heshmati R, smaeilpour K. [Effectiveness of group narrative therapy on ego strength of female-headed households (Persian)]. Policewomen Studies Journal. 2020; 14(32):5-17. [Link]

- Jafari F, Heydarnia A, Abbassi H. [The effectiveness of group narrative therapy on depression in divorced women (Persian)]. Rooyesh. 2019; 8(5):217-22. [Link]

- Luthans F, Avolio BJ, Avey JB, Norman SM. Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology. 2007; 60(3):541-72. [DOI:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00083.x]

- Simar Asl N, Fayazi, M. [Psychological capital: A new basis for competitive advantage (Persian)]. Tadbir. 2008; 200:44-8. [Link]

- Hashemi Nosratabad T, Babapur Kheyroddin J, Bahadori Khosroshahi J. Role of psychological capital in psychological wellbeing by considering the moderating effects of social capital. Social Psychology Research. 2012; 1(4):123-44. [Link]

- Fooladi K, Ahmadi R, Sharifi T, Ghazanfari A. [Effectiveness of group narrative therapy on psychological wellbeing and cognitive emotion regulation of mothers of children with hearing impairment (Persian)]. Empowering Exceptional Children. 2021; 12(2):1-11. [DOI:10.22034/ceciranj.2021.237671.1410]

- Khodayarifard M, Sohrabpour G. [Effectiveness of narrative therapy in groups on psychological well-being and distress of Iranian women with addicted husbands (Persian)]. Addiction and Health. 2018; 10(1):1-10. [Link]

- Skerrett K. "Good enough stories": Helping couples invest in one another's growth. Family Process. 2010; 49(4):503-16. [DOI:10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01336.x] [PMID]

- Procheska JaN, John. Systems of psychotherapy: A transtheoretical analysis. [Y Seyed Mohammadi, Persian trans]. Tehran: Ravan; 2014. [Link]

- Caldwell RL. At the confluence of memory and meaning—Life review with older adults and families: Using narrative therapy and the expressive arts to re-member and re-author stories of resilience. The Family Journal. 2005; 13(2):172-5. [DOI:10.1177/1066480704273338]

- Malcolm LE, Ramsey JL. On forgiveness and healing: Narrative therapy and the Gospel story. Word & World. 2010; 30(1):23. [Link]

- Fivush R, Bohanek JG, Zaman W. Personal and intergenerational narratives in relation to adolescents' well-being. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2011; 2011(131):45-57. [DOI:10.1002/cd.288] [PMID]

Article type: Original Research Articles |

Subject:

Psychology

Received: 2022/10/14 | Accepted: 2023/02/7 | Published: 2023/12/1

Received: 2022/10/14 | Accepted: 2023/02/7 | Published: 2023/12/1

Send email to the article author