Volume 22, Issue 2 (June 2024)

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2024, 22(2): 183-194 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Tohidast S A, Nahidi R, Mansuri B, Salmani M. Effects of Children’s Communication Disorders on the Quality of Life of Their Parents in Iran. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2024; 22 (2) :183-194

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1873-en.html

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1873-en.html

1- Neuromuscular Rehabilitation Research Center, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran.

2- Student Research Committee, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran.

3- Department of Speech Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran.

2- Student Research Committee, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran.

3- Department of Speech Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 597 kb]

(1049 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3332 Views)

Full-Text: (680 Views)

Introduction

Quality of life (QoL) has received special attention in health and social science studies [1]. Different definitions of QoL have been proposed so far; for example, the World Health Organization (WHO) defines QoL as an individual’s perception of their position in life, the cultural context, the value system of the environment, and concerning its goals, expectations, standards, and dependencies [2]. WHO states that QoL should be assessed in terms of the environment, society, and culture of the individual, and it is not enough to only examine a person’s health status, lifestyle, life satisfaction, mental state, and sense of well-being. Therefore, the tool for measuring QoL should consider many aspects of a person’s life in their cultural and social context [2]. Finally, a multi-dimensional model of QoL can be considered the most acceptable model in this regard [3]. In addition to the importance of QoL in the health sciences, there is also a great deal of attention to the concept of family system in disease and health. According to the family system theory, the disease in each family member affects the whole family (i.e. self, parents, other children, and caregivers). Meanwhile, the presence of chronic disease in children can widely change communication patterns, roles, and family relationships [4]. Studies have specified that any of the developmental communication disorders (or speech-language disorders), such as speech impairment [5, 6], hearing impairment [5, 7] and stuttering [8] negatively affects the function of the whole family; therefore, family members face many problems. Some of the problems of families in such cases include more anxiety, depression, stress and worries [5, 9-11], mental and physical problems [12-14], self-isolation and social isolation [13], work problems and resignation [15], and financial issues [16]. Such problems consequently reduce the parents’ QoL [7, 10, 14]. The parents’ QoL affects the parenting roles and treatment processes of their children [17]. Accordingly, therapists working in this field need to be informed regarding factors affecting the conditions of the children’s families and address them to provide a more desirable treatment plan for children. Parents who have a higher QoL can provide better conditions to improve their child’s condition [12, 18]. However, parents who face many problems in their lives and do not have a good QoL cannot provide high-quality care and are forced to ignore the needs of their children [19]. When parents have physical or psychological problems, they are occupied with their treatments, thus the child’s problems would be out of their focus. For example, higher levels of stress experienced by these parents can be harmful to the parent-child relationship [18, 20]. Financial issues prevent parents from having access to the resources and facilities to take good care of their children or to provide them with ideal treatments [20].

Accordingly, when parents confront communication problems in any of their children, they experience various problems, such as difficulties in communicating with the affected child, high levels of stress, excessive strain, limited daily life activities, and problems in delivering proper parenting roles [5, 6, 21, 22]. These problems consequently affect the QoL of the child with communication disorder and other family members [4, 5].

So far studies that examined the parents’ QoL in this field had a narrow perspective. Their focus was on children with specific communication disorders, such as speech impairment, hearing loss, and stuttering. They had a quantitative approach using common questionnaires, including the 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36), the WHO QoL–BREF (WHOQOL-BREF), and the 12-item short-form health survey (SF-12) [1, 5, 12, 15, 23, 24]. Allik et al. [12] investigated parents’ QoL of children with autism and Asperger using the SF-12 questionnaire. Mothers of children with autism and Asperger had a lower SF-12 score compared to the control group, which indicates lower physical health. Also, these mothers had a lower physical score compared to fathers [12]. In another study, Dardas & Ahmad [25] evaluated the QoL of parents of children with autism via the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire. They reported that having a child with autism can have a significant negative impact on the parents’ QoL. In a study by Aras et al. [5] using the SF-36 questionnaire, parents of children with speech and hearing impairment participated. In all groups of parents, mothers had a lower score than fathers. Compared to the control group, both groups of fathers and mothers of children with speech defects were significantly worse in the five health domains. Therefore, parents of preschool-age children with speech impairment and hearing loss experienced a lower QoL than parents of healthy children of the same age. Zerbeto et al. [24] used the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire to investigate the QoL in caregivers of children and adolescents with speech and language disorders and reported that this population had low QoL. These quantitative studies can provide fast, factual, and reliable data that can be generalized to some larger populations. Moreover, quantitative studies used questionnaires to evaluate QoL is suited to investigate hypotheses, determine causal relationships, and determine the opinions, attitudes, and practices of a large sample size [26]. These studies, regardless of these advantages and their large samples, evaluated the QoL by a few limited questions of the applied questionnaires. However, qualitative studies are well to describe processes like communication processes or decision-making and develop hypotheses and theories. Furthermore, qualitative studies provide rich, detailed, and valid data according to participants, instead of investigators, interpretations, and perspectives [26]. Since QoL is a concept not easily defined and cannot be considered merely related to physical and mental health, lifestyle, and life satisfaction, the QoL should be considered as a multidimensional concept on which people’s perception has a great impact [27]. Therefore, professionals need studies in this field that have a full, comprehensive, and in-depth evaluation of the parents’ QoL. Qualitative studies may satisfy the professionals’ needs. With qualitative studies, focused on the QoL of parents who have children with communication disorders, complementary data and expansion of the previous results provided by quantitative studies can be attained. Additionally, professionals would have several advantages not obtained by the quantitative approach. Qualitative studies can explore aspects of reality that may not be quantified by questionnaires [28]. Also, they can introduce new domains of parents’ QoL affected by children’s communication disorders not mentioned by the previous quantitative studies. Exploratory, detailed, and flexible entities in data collection and analysis processes of qualitative studies are advantages that could not be achieved through quantitative studies [28]. Moreover, the results of qualitative studies may provide implications for developing new questionnaires regarding the investigated subjects. According to the advantages of qualitative studies, the current study implements a qualitative approach to evaluate the QoL of parents who had children with communication disorders. The current study clarifies the effects of the child’s communication on known and unknown aspects of parents’ QoL.

Materials and Methods

Study participants

This was a qualitative study to determine the effects of communication disorders in children on parents’ QoL. To this end, the purposeful sampling method was applied. The participants of the study consisted of parents who had children with communication disorders and had been referred to the University Clinics to receive speech-language therapy services. All children had received between one and ten sessions of speech therapy. The inclusion criteria were having a preschool-age child with communication disorders (such as stuttering, developmental language disorder, speech sound disorder, and hearing impairment) without any disorder/disability apart from the mentioned communication problems. Additionally, parents with any physical illness or mental disorder were excluded from the study. An experienced SLP evaluated all children and confirmed the presence of communication disorders. The same SLP interviewed parents to check out their general health or specific disorders/diseases. The researcher investigated these cases based on the statements of the parents and the medical records of the children and parents. In case of a possibility of any disorder in the parents, they were excluded from the study.

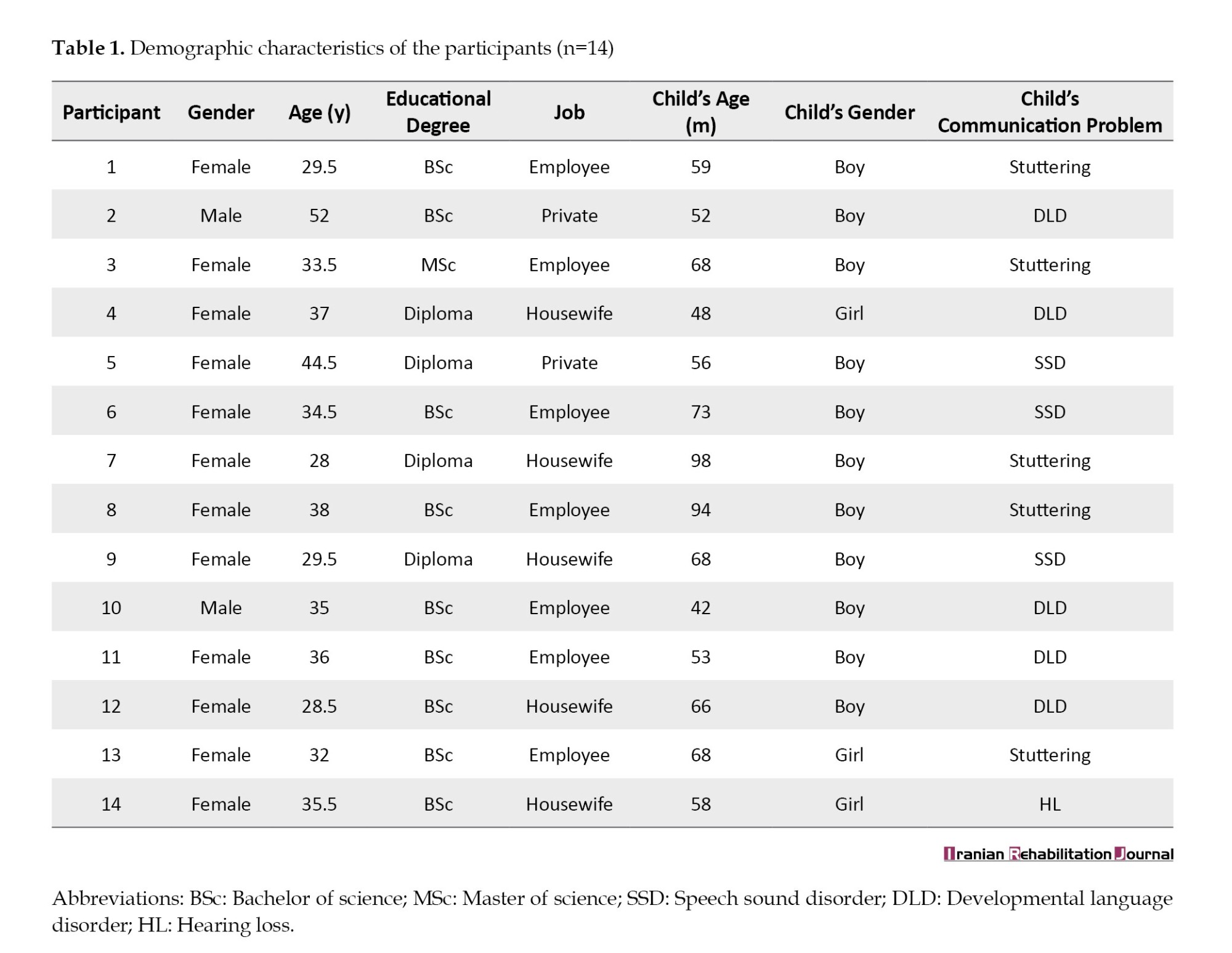

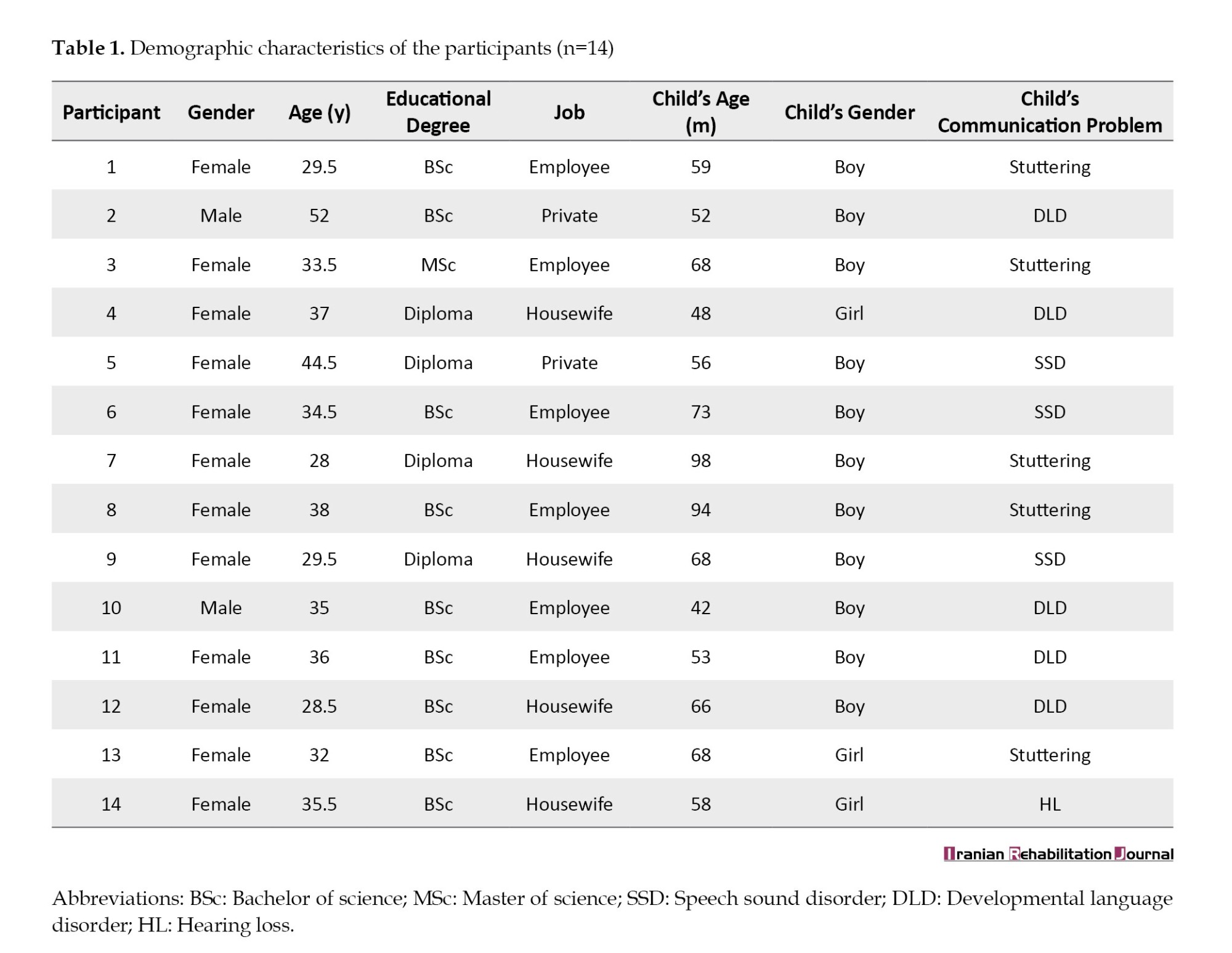

A total of 14 parents (12 mothers and 2 fathers) of children with communication disorders who were willing to participate in the study signed the consent form and cooperated to the end of the present study. The mean age of parents was 35.25 years and the mean age of their children was 64.5 months. Meanwhile, 11 children were boys and 3 were girls. The diagnosis of communication disorders in the children was as follows: Five children with stuttering, five children with developmental language disorder, three children with speech sound disorder, and one child with language disorder (because of the hearing impairment). Table 1 provides more details about the demographic characteristics of the participants.

The researchers assured the families that this study did not have any harm to them or their children and that every piece of information regarding parents and their children would be confidential and anonymous during the study and in publishing data. If the parents decided to stop their cooperation during any stage of study or even withdraw their information, there would not be any financial or social consequences for them or their children.

Data collection

This was a qualitative study that applied conventional content analysis [29]. The conventional content analysis introduced by Hsieh and Shannon (2005) was a procedure to describe a phenomenon when the available theory, knowledge, or literature could not provide enough information [29]. To apply this procedure, the research team employed an inductive analysis of interview transcriptions. They transcribed each interview, extracted related statements, defined meaning units, labeled the primary codes, composed the similar primary codes to produce subthemes, and according to the subthemes, they introduced the final themes. To run such a procedure, the research team should immerse themselves in the study data to have new perceptions and insight into the collected data. Thus, there would not be any predetermined categories, but this was the research team that extracted the themes from the collected data [29].

In the current study, the effects of children’s communication disorders on their parents’ QoL were explored. To do so, all parents should have been interviewed. The interviews were conducted over six months from January to June 2021. A speech-language pathologist (SLP) invited all parents by phone or in person. Parents were free to choose the place of interviews where they could attend and be comfortable and the SLP could run the interviews. All parents chose the university speech therapy clinics during working hours. All interviews were conducted without the presence of children. The SLP ran the interviews face-to-face and recorded whole sessions using a digital voice recorder (Sony model). She started the interviews with open-ended questions and based on the answers of the participants in the study, she continued with complementary and exploratory questions (such as “explain more,” “please give me an example”) to further examine the experiences of the participants. The average duration of the interviews was 52 min, and the minimum and maximum interview durations were 35 and 62 min, respectively. When the SLP finished each interview, she transcribed the whole session word by word by listening to the recorded voices. She returned the transcript to the participant and asked for a recheck and confirmation. The SLP was accessible through a landline phone number to be able to answer possible questions that participants might have after interviews. The research team agreed on the following questions as an interview guide selected from the available literature. The lead questions were as follows:

“What effects has your child’s communication disorder had on your QoL?”

“What effects has your child’s communication disorder had on your mood and that of other members of your family?”

“What effects has your child’s communication disorder had on your physical condition and that of other members of your family?”

“What effects has your child’s communication disorder had on your relationship with your spouse?”

“What effects has your child’s communication disorder had on your relationship with your kids?”

“What effects has your child’s communication disorder had on your family’s financial situation?”

“What effects has your child’s communication disorder had on your relationship with your relatives and friends?”

“What effects has your child’s communication disorder had on your career and education?”

“What effects did your child’s communication disorder have on your hobbies and leisure activities?”

The research team acted purposefully in selecting participants to achieve maximum variety in the samples. Therefore, the participants were from both genders, with different ages, educational degrees, socio-economic status, and children with various communication disorders. The research team continued sampling up to data saturation, i.e. when the analysis of the transcripts did not lead to a new code, and the classification of information, concepts, and the relationship among these categories were well defined.

Study analysis

The research team analyzed interviews based on the Graneheim and Lundman method [30]. The analysis method included the following steps: 1) Transcribing the entire interview immediately after each interview (transcribing); 2) Reading the text of the interview several times to understand its general content and determine the codes and semantic units (extracting meaning units); 3) Abstracting meaningful units and primary codes (abstracting), primary codes are labels that are attached to meaningful units, and more abstract codes are better; 4) Classification of primary codes into more comprehensive subthemes based on their similarity (sorting codes); 5) Determining the main themes and major contents hidden in the data (formulating themes). The reliability of data was evaluated by the criteria proposed by Lincoln and Guba [31, 32].

After analyzing each interview, the next interview was conducted and new data were added to the previous sets and the initial codes based on the existing similarities of the subthemes, and then the subthemes formed the initial themes. The first six parents’ interviews were investigated by the Seyed Abolfazl Tohidast to develop a primary coding tree according to the most prevalent themes that emerged from data analysis. Some examples of initial codes include “the lack of time for other family members” and “feeling guilty about a child’s disorder.” Then, all transcripts of the interviews were analyzed and coded by the Banafshe Mansuri, in the same manner with new codes added, renamed, or merged as additional themes were extracted. Data analysis and coding were re-examined by the mentioned authors for consistency and accuracy in developing a coding tree. The transcripts were then analyzed for a final time to ensure all data of interest was captured by the coding tree. The codes and themes formed after all the interviews were reviewed several times to create the final subthemes and themes. After 12 interviews, we reached data saturation and no new data codes appeared. To ensure this, two more interviews were conducted. By definition, data saturation in the qualitative study takes place when the researcher reaches a point in the study process where no new information can emerge in the data analysis procedure. This point in the study process signifies to the research team that data collection may be finished. Data saturation has been considered the most frequent guiding principle to evaluate the sufficiency of the purposive sampling method in qualitative studies. However, different factors make it difficult to have a practical guideline for saturation, such as the topic, participants and design of the studies. Therefore, data saturation is not related to the number of conducted interviews but is related to the data richness and thickness [33, 34]. In the present study, when the data analysis did not produce new data, new codes, and new themes, the sampling was ceased [34]. After data analysis, the extracted themes and subthemes were sent to the parents who participated in the study to verify these analyses and comment on them.

Results

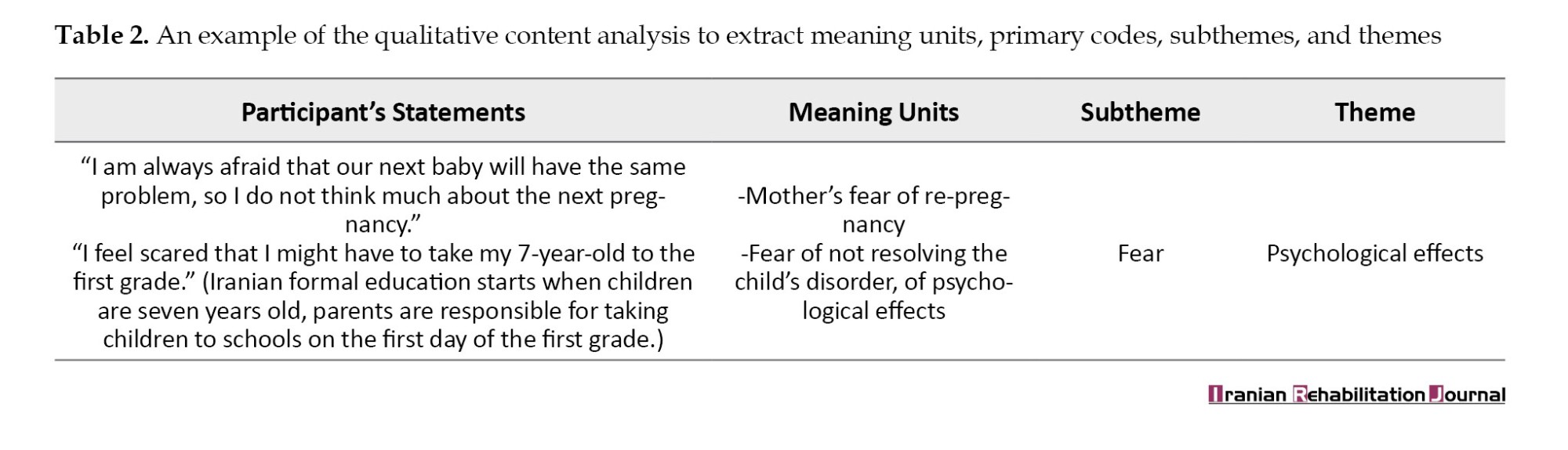

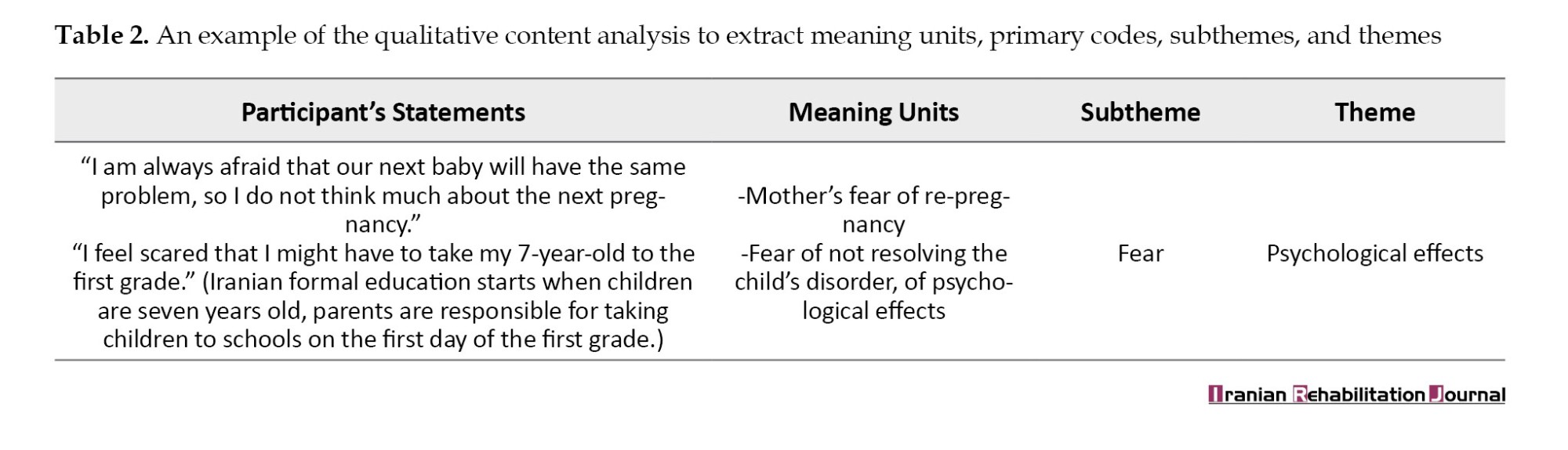

Qualitative content analysis of the interviews with parents of children with communication disorders led to the emergence of meaning units, primary codes, subthemes, and finally the themes. Table 2 shows an example of meaning units, subthemes, and themes that emerged from the content analysis of the interviews. Analyzing the whole 14 transcriptions of the interviews led to the emergence of five main themes, including physical effects, psychological effects, economic effects, family dynamics effects, and job-educational effects.

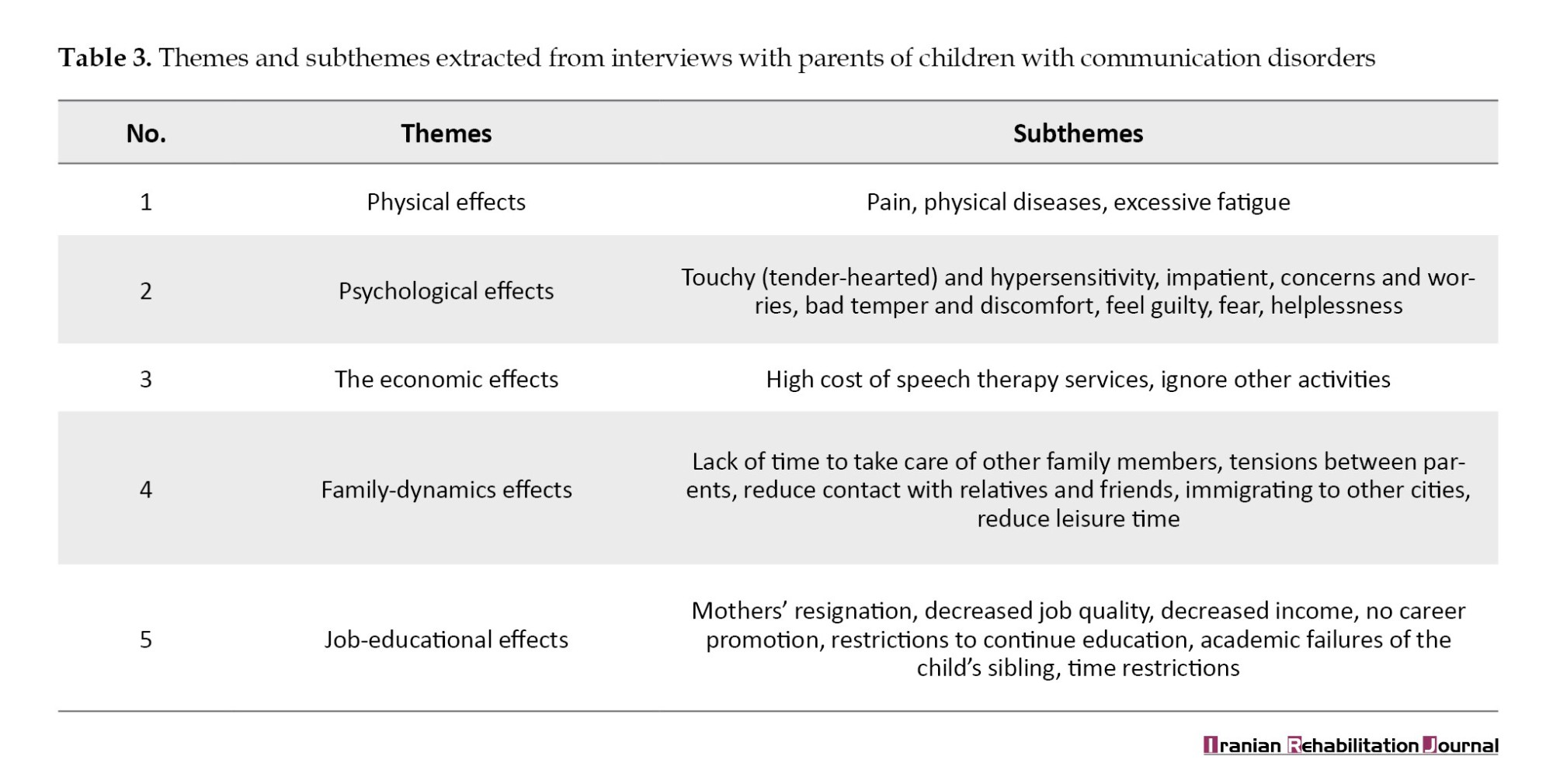

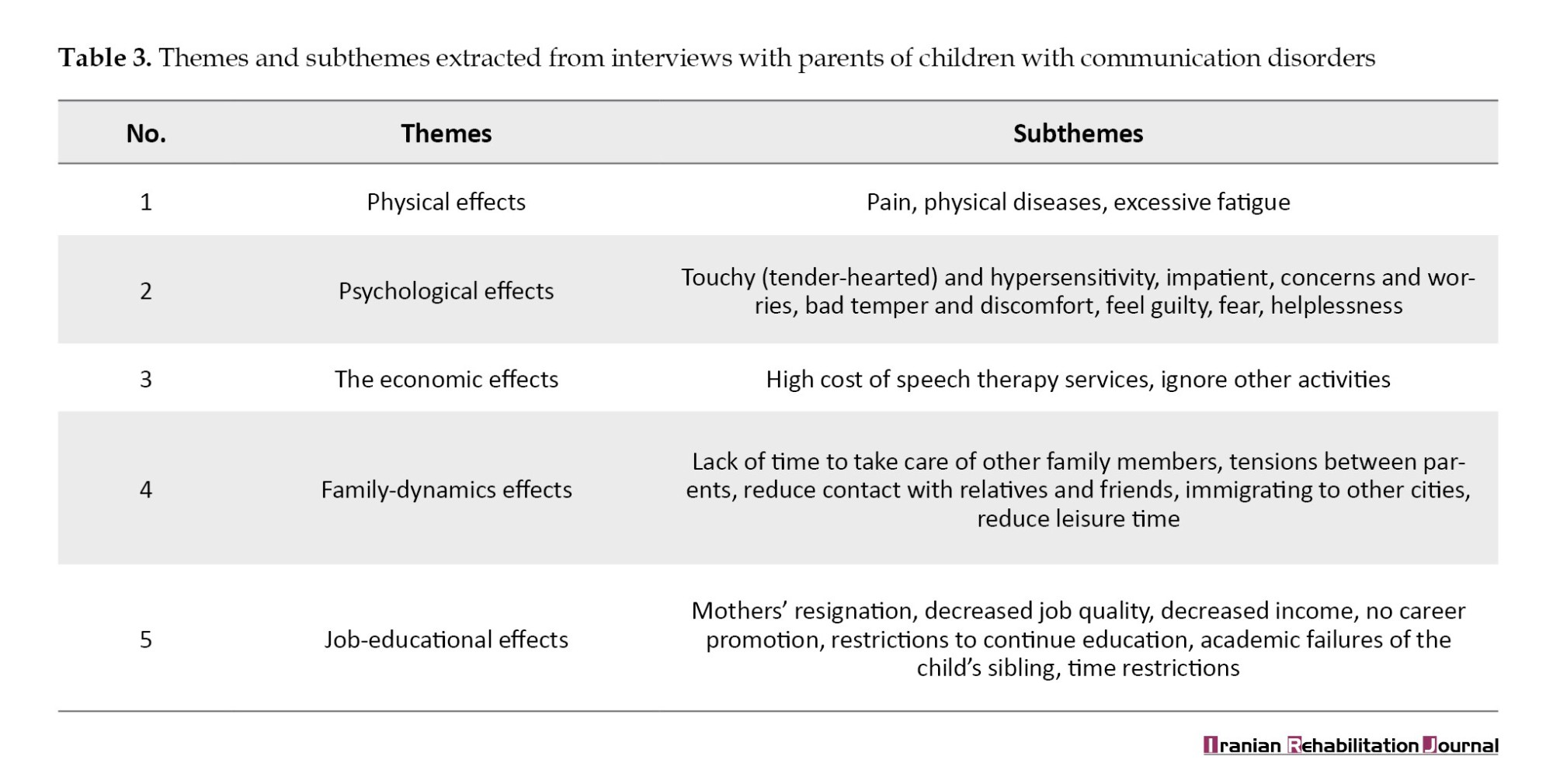

Moreover, each theme includes several subthemes. It is not common in qualitative studies to report figures, the maximum, or the minimum; however, by precise observation, the most frequent and important theme mentioned was psychological effect and the least frequent theme was economic effects. Table 3 presents themes and subthemes that emerged from the interviews.

Physical effects

Parents believed that pain, physical illness, and fatigue were among the negative effects of their children’s communication disorders. Some of the parents’ quotes about physical pain were as follows: “I used to come to Semnan City, Iran, in the heat of summer; I just said that my kid got well, I would get bad headaches,” (Third participant). Another parent, referring to fatigue from receiving medical care said: “I do everything quickly on Sundays and Tuesdays when I come to speech therapy. I’m very tired and sleepy and eat standing up,” (First participant).

One parent believed that the psychological effects of a child’s problems were greater than the physical effects: “It did not have much of a physical effect on me, it was more psychological,” (12th participant).

Psychological effects

The psychological effects were the most frequent and important theme reported by the parents who participated in the study. Most of the participants believed psychological effects were the major group of negative effects that communication disorders had on the child’s family. These negative effects included: Touchy (tender-hearted) and hypersensitivity, impatient, anxiety, moodiness and sadness, guilt, fear, and helplessness. A large number of parents who participated in the study reported that impatient was one of the psychological problems they experienced: “My patience has been reduced, and I will lose my temper so fast,” (Fourth participant).

One parent who felt guilty about their child’s problem said “I always say, and last night I told a friend of mine who had just given birth. The children really should have their mothers by their side, but I was not with my child. My friend told me I quit my job and told them you did a good job,” (Sixth participant).

Anxiety about the future was also one of the negative psychological effects that were widely discussed by the participants. The remarks of two parents were as follows: “We are worried about his/her future because of his/her stuttering since there are also educated people around us who tell me that it is a pity that the child becomes an engineer or a doctor or have an important job and he cannot talk. We are getting so worried,” (Eighth participant). “She/he is three and a half years old now, but I am always worried about his/her future. Now she/he goes to kindergarten, children are less aware of her/his problems, but I am afraid that children will tell her/him at school (about her/his problems) and cause her/him frustration or loss of self-confidence,” (11th participant).

Economic effects

This theme was the least frequent theme reported by the participants. Parents who participated in the study reported that economic problems are another negative effect caused by children’s communication disorders. They reported that the high cost of speech therapy services for their children has caused many financial problems for them. one of the parents said “to treat my child’s stuttering, I have to take him to speech therapy two to three times a week. The high cost of speech therapy and the lack of insurance coverage for speech therapy have caused us a lot of financial problems,” (First participant).

Also, the parents believed that due to the high cost to the child with communication problems, they cannot afford to spend well on other activities for their child, such as sports classes, leisure, travel, and shopping clothes.

Family-dynamics effects

The participants believed that their child’s condition had negative influences on family-related aspects of their lives. Many parents reported the lack of time to take care of other family members, tensions between parents, reduced catching up with relatives and friends, migration to other cities, and reduced leisure time as the negative family dynamics effects caused by their children’s problems. “I cannot take care of my little one at all,” said one parent about the lack of time to take care of other family members,” (13th participant).

Another participant said of the tension between the parents: “His/her father did not feel responsible at all, he did not think about her/him, and I always argued with him about this issue and told him to follow up [the problem] until she/he was little, that he did not think at all,” (11th participant).

Another negative social effect expressed by the parents was the reduction of contact with relatives, one of the mothers said about this issue: “When we went somewhere (child’s name) he/she was bothered, we did less (we reduced the frequency of visiting) for his/her sake because he could not say anything and what he wanted to say,” (Fifth participant).

Job-educational effects

The parents frequently mentioned that their work and education, as the most important aspects of a person’s life, were under negative influences. This theme was extracted from the following categories: Mothers’ resignation, decrease in job quality, decrease in income, a lack of job promotion, restriction on continuing education, academic failure child’s sibling, and time restriction. Some of the parents’ statements in this regard were as follows:

“I have quit my job because of my son,” (Third participant).

“I go to the edge of being fired. There is a certain limit to taking leave and things get very double. Every time the kindergarten rings, I go to the kindergarten in a panic, which would not have happened if I had not been employed,” (First participant).

The ninth participant about the negative impact on his/her job and education and the lack of proper conditions to continue his/her education said: “Maybe if we didn’t have these problems, I would have continued my education or a proper job would have happened, but now I can’t because of the child’s problem.”

In summary, the content analysis revealed that the effects of children’s communication disorders could be classified into five different themes. The data analysis emerged themes and subthemes were sent to the parents who were willing to collaborate at this stage of the study to verify themes and subthemes. These findings and analysis were confirmed by the parents. While the research team searched for the core themes, supplemental or complementary themes did not come up.

Discussion

This study was conducted to explain the effects of children’s communication disorders on their parents’ QoL. According to the results of the present study, communication disorders in children can cause many negative effects on the parents’ QoL, including physical effects, psychological effects, economic effects, family-dynamic effects, and job-educational effects. The negative effects of children’s communication disorders on parents’ QoL were consistent with findings reported by the previous studies that investigated the QoL in parents of children with hearing loss [5], speech impairment [6], stuttering [8, 35], pervasive developmental disorders (autism and Asperger) [12, 27, 36], intellectual disability [37, 38], cerebral palsy [15, 16], and cancer [1]. However, what these studies reported were according to the common questionnaires of QoL such as SF-36 that led to a general understanding of the physical, emotional, mental, and well-being status of parents [6]. They could not provide a specific assessment of parents’ lives or perceptions. Thus, the overall picture (negative effect of child’s disorders on parents’ QoL) presented by this study came out similar to the pictures provided by the previous studies; however, the present study provided striking features of effects of child’s communication disorders on parents’ QoL. The in-depth, specific, and detailed findings of the current study could not be compared or achieved by the quantitative studies.

The physical and psychological problems that parents have raised concerns in this study and confirmed the findings of the previous studies have many negative effects on the parents’ QoL [12, 13, 38]. Parents who participated in the study experienced pain, physical disease, and excessive fatigue. Many trips in difficult conditions, such as hot weather to receive treatment sessions for children, the need to quickly perform personal activities for mothers, improper sleep, improper eating conditions, and numerous fatigues have caused physical problems for parents of children with communication disorders. Previous studies have examined the effects of a child’s speech impairment or stuttering on parents’ QoL but have not reported the types of physical problems in parents due to their child’s problem. Such finding is an artifact of the applied questionnaire which provided only a score and the researchers concluded that parents of children with speech impairment had lower scores in physical functioning subscales than parents of healthy children [5, 6]. Studies with a qualitative approach who recruited parents of children with cerebral palsy, autism spectrum disorders, and intellectual disabilities reported physical problems in line with the current study.

The other theme in the present study was the psychological effects. Parents of children with communication disorders reported touchy (tender-hearted) and hypersensitivity, impatient, concerns and worries, bad temper and discomfort, feeling guilty, helplessness, and fear as some of the most negative psychological problems due to their children’s problems. Some of these problems were reported by parents of children who stutter in the previous studies. Parents of children who stutter reported helplessness, frustration, anxiety, feeling guilt or self-blame, stress and worry [8, 35, 39]. The difference between this study and the studies on the effects of stuttering on parents’ QoL might be a consequence of the recruited participants, we interviewed parents of children with different types of communication disorders and they only focused on parents of children who stutter. Since all the interviewed parents in the present study mentioned psychological problems as the most important problems, the clinicians and researchers who are active in this field should consider the psychological problems in parents during the assessment and intervention properly, especially by SLPs. In a study conducted in Sri Lanka, parents of children who stutter reported that they had not received proper attention from SLPs regarding their psychological and emotional problems [35].

The other theme in the present study about the negative effects of a child’s communication disorder on parents’ QoL was economic problems. This economic problem was reported in the previous studies that investigated the effects of children’s stuttering on parents’ lives [39]. Such economic problems may look familiar for all disorders or diseases, but it highlights the need for special and comprehensive attention from the related agencies which could be the governments’ organizations or private companies. In this case, providing complementary and private insurance as well as services and support from public health organizations would be deeply valued. Additionally, the obstacles of insurance support for rehabilitation services, especially for speech-language pathology services, should be removed to reduce the burden on parents during the process of assessment and intervention for their children’s communication disorders [38].

The negative job-educational effects reported by parents in this study and previous studies with a focus on the effect of cerebral palsy [15, 16] were similar. Whereas, the nature of communication disorders is not similar to the nature of cerebral palsy, finding such effects may show how depth a communication disorder would affect. Such job-educational effects of communication disorder have not been reported by the previous studies that recruited children with speech or language impairments.

One of the outstanding results of the present study was the negative effects of a child’s communication disorder on the “family dynamics.” This finding confirms the pervasive nature of communication disorder on parents’ QoL, an aspect that previous studies did not mention or report. In this case, the child’s communication disorders have negative effects on parents’ interactions, their roles, and relationships with other kids, relatives, and friends. They reported how the child’s communication disorder reduced their opportunity to have leisure activities or time. Family dynamics is the primary source of relationship security or stress (since family members support each other emotionally, physically, and financially) [40] and the present study showed how this primary source was affected by the child’s communication disorder. When the family relationship is stressful instead of secure, the home environment would be troubled with arguments, endless critical comments/reactions, and onerous demands [40, 41]. Affected family dynamics would influence the health and recovery outcomes, and have enough values to be considered in clinical settings. When the family dynamics do not work properly, it may cause a child to experience adverse childhood trauma (stress and trauma) as he/she grows up. Studies have indicated that adverse childhood trauma is connected to an intensified risk of emerging physical and mental health issues [41, 42]. Therefore, we may be able to conclude that there is a cycle between a child’s communication disorder, family dynamics, and negative childhood experience, although further studies warranted exploring such a relationship.

The present study confirmed and extended the findings of the previous studies that showed how communication disorder in a child could negatively affect the QoL of parents, and emphasized the highly threatening nature of these disorders on parents’ lives. The present study provided supportive documents on how the families of children with communication disorders need to receive special attention from private and public health systems to be able to elevate their QoL. Using social workers and counselors with proper knowledge and experience in this field and their presence in the rehabilitation team can be useful in improving the families’ living conditions [38].

Future studies may use the findings of the present study to develop a questionnaire or scale to assess the caregiver burdens or QoL among parents who have children with communication disorders. This study took the first step in developing new questionnaires or scales with a qualitative design. It could find the main concepts related to the studies concerned about the effects of communication disorders on parents. Even, the extracted themes, subthemes, and codes in the current study can be used to define the subcategories and primary items of the related questionnaires. Meanwhile, in making new questionnaires and scales, the researchers should add up the findings of the interviews with a review of the literature (two important sources for item generation).

Conclusion

The current study explained the negative effects of communication disorders on children on parents’ QoL with a qualitative research design. According to parents’ reports, communication disorders in children can cause several negative effects on parents’ life included physical, psychological, economic, social-communication, and job-educational effects. These negative effects justify the need to provide more support for the children’s family as well as more attention to the parent’s QoL. These results can be useful for policymakers, researchers, and service providers in the field of assessment and treatment of communication disorders. It is better that future studies can investigate the parents’ QoL with quantitative methods to generalize the results of the present study. Moreover, the findings of the current study can be used for the development of new instruments for measuring caregiver burden and QoL among parents of children with communication disorders and their parents.

Study limitation

The generalization of our findings is limited because of some issues. The number of fathers who participated was not comparable to the number of mothers. Replicating this study with a sample that included more fathers might reach to different perspective about the effects of communication disorders in children on parents’ QoL. Data collection and interviews with parents were performed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the effects of the pandemic situation on peoples’ lives should be considered. Since the data was collected by interview in a qualitative study, participants’ abilities to talk about their problems and their assertiveness in this case might have some effects. According to Grice’s cooperative principles, those people who consider quantity, quality, relation, and manner to provide information would decrease the language implicature during a conversation or interview. Thus, participants who talk more about the subject under study comment on various topics, and present several examples would increase the comprehensiveness and depth of the information.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research approved by the Ethical Committee of Semnan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.-UMS.REC.1397.279).

Funding

This article is financially supported by the Student Research Committee in Semnan University of Medical Sciences (Grant No.: 1377).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and writing the original draft: Banafshe Mansuri, Seyed Abolfazl Tohidast and Masoomeh Salmani; Methodology: Seyed Abolfazl Tohidast and Banafshe Mansuri; Investigation: Rezvaneh Nahidi and Seyed Abolfazl Tohidast; Funding acquisition: Rezvaneh Nahidi and Seyed Abolfazl Tohidast; Review and Editing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

All the researchers of this study wish to thank the Vice Chancellor for Research of the Semnan University of Medical Sciences as well as its staff and families of children with communication disorders who participated in the study.

References

Quality of life (QoL) has received special attention in health and social science studies [1]. Different definitions of QoL have been proposed so far; for example, the World Health Organization (WHO) defines QoL as an individual’s perception of their position in life, the cultural context, the value system of the environment, and concerning its goals, expectations, standards, and dependencies [2]. WHO states that QoL should be assessed in terms of the environment, society, and culture of the individual, and it is not enough to only examine a person’s health status, lifestyle, life satisfaction, mental state, and sense of well-being. Therefore, the tool for measuring QoL should consider many aspects of a person’s life in their cultural and social context [2]. Finally, a multi-dimensional model of QoL can be considered the most acceptable model in this regard [3]. In addition to the importance of QoL in the health sciences, there is also a great deal of attention to the concept of family system in disease and health. According to the family system theory, the disease in each family member affects the whole family (i.e. self, parents, other children, and caregivers). Meanwhile, the presence of chronic disease in children can widely change communication patterns, roles, and family relationships [4]. Studies have specified that any of the developmental communication disorders (or speech-language disorders), such as speech impairment [5, 6], hearing impairment [5, 7] and stuttering [8] negatively affects the function of the whole family; therefore, family members face many problems. Some of the problems of families in such cases include more anxiety, depression, stress and worries [5, 9-11], mental and physical problems [12-14], self-isolation and social isolation [13], work problems and resignation [15], and financial issues [16]. Such problems consequently reduce the parents’ QoL [7, 10, 14]. The parents’ QoL affects the parenting roles and treatment processes of their children [17]. Accordingly, therapists working in this field need to be informed regarding factors affecting the conditions of the children’s families and address them to provide a more desirable treatment plan for children. Parents who have a higher QoL can provide better conditions to improve their child’s condition [12, 18]. However, parents who face many problems in their lives and do not have a good QoL cannot provide high-quality care and are forced to ignore the needs of their children [19]. When parents have physical or psychological problems, they are occupied with their treatments, thus the child’s problems would be out of their focus. For example, higher levels of stress experienced by these parents can be harmful to the parent-child relationship [18, 20]. Financial issues prevent parents from having access to the resources and facilities to take good care of their children or to provide them with ideal treatments [20].

Accordingly, when parents confront communication problems in any of their children, they experience various problems, such as difficulties in communicating with the affected child, high levels of stress, excessive strain, limited daily life activities, and problems in delivering proper parenting roles [5, 6, 21, 22]. These problems consequently affect the QoL of the child with communication disorder and other family members [4, 5].

So far studies that examined the parents’ QoL in this field had a narrow perspective. Their focus was on children with specific communication disorders, such as speech impairment, hearing loss, and stuttering. They had a quantitative approach using common questionnaires, including the 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36), the WHO QoL–BREF (WHOQOL-BREF), and the 12-item short-form health survey (SF-12) [1, 5, 12, 15, 23, 24]. Allik et al. [12] investigated parents’ QoL of children with autism and Asperger using the SF-12 questionnaire. Mothers of children with autism and Asperger had a lower SF-12 score compared to the control group, which indicates lower physical health. Also, these mothers had a lower physical score compared to fathers [12]. In another study, Dardas & Ahmad [25] evaluated the QoL of parents of children with autism via the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire. They reported that having a child with autism can have a significant negative impact on the parents’ QoL. In a study by Aras et al. [5] using the SF-36 questionnaire, parents of children with speech and hearing impairment participated. In all groups of parents, mothers had a lower score than fathers. Compared to the control group, both groups of fathers and mothers of children with speech defects were significantly worse in the five health domains. Therefore, parents of preschool-age children with speech impairment and hearing loss experienced a lower QoL than parents of healthy children of the same age. Zerbeto et al. [24] used the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire to investigate the QoL in caregivers of children and adolescents with speech and language disorders and reported that this population had low QoL. These quantitative studies can provide fast, factual, and reliable data that can be generalized to some larger populations. Moreover, quantitative studies used questionnaires to evaluate QoL is suited to investigate hypotheses, determine causal relationships, and determine the opinions, attitudes, and practices of a large sample size [26]. These studies, regardless of these advantages and their large samples, evaluated the QoL by a few limited questions of the applied questionnaires. However, qualitative studies are well to describe processes like communication processes or decision-making and develop hypotheses and theories. Furthermore, qualitative studies provide rich, detailed, and valid data according to participants, instead of investigators, interpretations, and perspectives [26]. Since QoL is a concept not easily defined and cannot be considered merely related to physical and mental health, lifestyle, and life satisfaction, the QoL should be considered as a multidimensional concept on which people’s perception has a great impact [27]. Therefore, professionals need studies in this field that have a full, comprehensive, and in-depth evaluation of the parents’ QoL. Qualitative studies may satisfy the professionals’ needs. With qualitative studies, focused on the QoL of parents who have children with communication disorders, complementary data and expansion of the previous results provided by quantitative studies can be attained. Additionally, professionals would have several advantages not obtained by the quantitative approach. Qualitative studies can explore aspects of reality that may not be quantified by questionnaires [28]. Also, they can introduce new domains of parents’ QoL affected by children’s communication disorders not mentioned by the previous quantitative studies. Exploratory, detailed, and flexible entities in data collection and analysis processes of qualitative studies are advantages that could not be achieved through quantitative studies [28]. Moreover, the results of qualitative studies may provide implications for developing new questionnaires regarding the investigated subjects. According to the advantages of qualitative studies, the current study implements a qualitative approach to evaluate the QoL of parents who had children with communication disorders. The current study clarifies the effects of the child’s communication on known and unknown aspects of parents’ QoL.

Materials and Methods

Study participants

This was a qualitative study to determine the effects of communication disorders in children on parents’ QoL. To this end, the purposeful sampling method was applied. The participants of the study consisted of parents who had children with communication disorders and had been referred to the University Clinics to receive speech-language therapy services. All children had received between one and ten sessions of speech therapy. The inclusion criteria were having a preschool-age child with communication disorders (such as stuttering, developmental language disorder, speech sound disorder, and hearing impairment) without any disorder/disability apart from the mentioned communication problems. Additionally, parents with any physical illness or mental disorder were excluded from the study. An experienced SLP evaluated all children and confirmed the presence of communication disorders. The same SLP interviewed parents to check out their general health or specific disorders/diseases. The researcher investigated these cases based on the statements of the parents and the medical records of the children and parents. In case of a possibility of any disorder in the parents, they were excluded from the study.

A total of 14 parents (12 mothers and 2 fathers) of children with communication disorders who were willing to participate in the study signed the consent form and cooperated to the end of the present study. The mean age of parents was 35.25 years and the mean age of their children was 64.5 months. Meanwhile, 11 children were boys and 3 were girls. The diagnosis of communication disorders in the children was as follows: Five children with stuttering, five children with developmental language disorder, three children with speech sound disorder, and one child with language disorder (because of the hearing impairment). Table 1 provides more details about the demographic characteristics of the participants.

The researchers assured the families that this study did not have any harm to them or their children and that every piece of information regarding parents and their children would be confidential and anonymous during the study and in publishing data. If the parents decided to stop their cooperation during any stage of study or even withdraw their information, there would not be any financial or social consequences for them or their children.

Data collection

This was a qualitative study that applied conventional content analysis [29]. The conventional content analysis introduced by Hsieh and Shannon (2005) was a procedure to describe a phenomenon when the available theory, knowledge, or literature could not provide enough information [29]. To apply this procedure, the research team employed an inductive analysis of interview transcriptions. They transcribed each interview, extracted related statements, defined meaning units, labeled the primary codes, composed the similar primary codes to produce subthemes, and according to the subthemes, they introduced the final themes. To run such a procedure, the research team should immerse themselves in the study data to have new perceptions and insight into the collected data. Thus, there would not be any predetermined categories, but this was the research team that extracted the themes from the collected data [29].

In the current study, the effects of children’s communication disorders on their parents’ QoL were explored. To do so, all parents should have been interviewed. The interviews were conducted over six months from January to June 2021. A speech-language pathologist (SLP) invited all parents by phone or in person. Parents were free to choose the place of interviews where they could attend and be comfortable and the SLP could run the interviews. All parents chose the university speech therapy clinics during working hours. All interviews were conducted without the presence of children. The SLP ran the interviews face-to-face and recorded whole sessions using a digital voice recorder (Sony model). She started the interviews with open-ended questions and based on the answers of the participants in the study, she continued with complementary and exploratory questions (such as “explain more,” “please give me an example”) to further examine the experiences of the participants. The average duration of the interviews was 52 min, and the minimum and maximum interview durations were 35 and 62 min, respectively. When the SLP finished each interview, she transcribed the whole session word by word by listening to the recorded voices. She returned the transcript to the participant and asked for a recheck and confirmation. The SLP was accessible through a landline phone number to be able to answer possible questions that participants might have after interviews. The research team agreed on the following questions as an interview guide selected from the available literature. The lead questions were as follows:

“What effects has your child’s communication disorder had on your QoL?”

“What effects has your child’s communication disorder had on your mood and that of other members of your family?”

“What effects has your child’s communication disorder had on your physical condition and that of other members of your family?”

“What effects has your child’s communication disorder had on your relationship with your spouse?”

“What effects has your child’s communication disorder had on your relationship with your kids?”

“What effects has your child’s communication disorder had on your family’s financial situation?”

“What effects has your child’s communication disorder had on your relationship with your relatives and friends?”

“What effects has your child’s communication disorder had on your career and education?”

“What effects did your child’s communication disorder have on your hobbies and leisure activities?”

The research team acted purposefully in selecting participants to achieve maximum variety in the samples. Therefore, the participants were from both genders, with different ages, educational degrees, socio-economic status, and children with various communication disorders. The research team continued sampling up to data saturation, i.e. when the analysis of the transcripts did not lead to a new code, and the classification of information, concepts, and the relationship among these categories were well defined.

Study analysis

The research team analyzed interviews based on the Graneheim and Lundman method [30]. The analysis method included the following steps: 1) Transcribing the entire interview immediately after each interview (transcribing); 2) Reading the text of the interview several times to understand its general content and determine the codes and semantic units (extracting meaning units); 3) Abstracting meaningful units and primary codes (abstracting), primary codes are labels that are attached to meaningful units, and more abstract codes are better; 4) Classification of primary codes into more comprehensive subthemes based on their similarity (sorting codes); 5) Determining the main themes and major contents hidden in the data (formulating themes). The reliability of data was evaluated by the criteria proposed by Lincoln and Guba [31, 32].

After analyzing each interview, the next interview was conducted and new data were added to the previous sets and the initial codes based on the existing similarities of the subthemes, and then the subthemes formed the initial themes. The first six parents’ interviews were investigated by the Seyed Abolfazl Tohidast to develop a primary coding tree according to the most prevalent themes that emerged from data analysis. Some examples of initial codes include “the lack of time for other family members” and “feeling guilty about a child’s disorder.” Then, all transcripts of the interviews were analyzed and coded by the Banafshe Mansuri, in the same manner with new codes added, renamed, or merged as additional themes were extracted. Data analysis and coding were re-examined by the mentioned authors for consistency and accuracy in developing a coding tree. The transcripts were then analyzed for a final time to ensure all data of interest was captured by the coding tree. The codes and themes formed after all the interviews were reviewed several times to create the final subthemes and themes. After 12 interviews, we reached data saturation and no new data codes appeared. To ensure this, two more interviews were conducted. By definition, data saturation in the qualitative study takes place when the researcher reaches a point in the study process where no new information can emerge in the data analysis procedure. This point in the study process signifies to the research team that data collection may be finished. Data saturation has been considered the most frequent guiding principle to evaluate the sufficiency of the purposive sampling method in qualitative studies. However, different factors make it difficult to have a practical guideline for saturation, such as the topic, participants and design of the studies. Therefore, data saturation is not related to the number of conducted interviews but is related to the data richness and thickness [33, 34]. In the present study, when the data analysis did not produce new data, new codes, and new themes, the sampling was ceased [34]. After data analysis, the extracted themes and subthemes were sent to the parents who participated in the study to verify these analyses and comment on them.

Results

Qualitative content analysis of the interviews with parents of children with communication disorders led to the emergence of meaning units, primary codes, subthemes, and finally the themes. Table 2 shows an example of meaning units, subthemes, and themes that emerged from the content analysis of the interviews. Analyzing the whole 14 transcriptions of the interviews led to the emergence of five main themes, including physical effects, psychological effects, economic effects, family dynamics effects, and job-educational effects.

Moreover, each theme includes several subthemes. It is not common in qualitative studies to report figures, the maximum, or the minimum; however, by precise observation, the most frequent and important theme mentioned was psychological effect and the least frequent theme was economic effects. Table 3 presents themes and subthemes that emerged from the interviews.

Physical effects

Parents believed that pain, physical illness, and fatigue were among the negative effects of their children’s communication disorders. Some of the parents’ quotes about physical pain were as follows: “I used to come to Semnan City, Iran, in the heat of summer; I just said that my kid got well, I would get bad headaches,” (Third participant). Another parent, referring to fatigue from receiving medical care said: “I do everything quickly on Sundays and Tuesdays when I come to speech therapy. I’m very tired and sleepy and eat standing up,” (First participant).

One parent believed that the psychological effects of a child’s problems were greater than the physical effects: “It did not have much of a physical effect on me, it was more psychological,” (12th participant).

Psychological effects

The psychological effects were the most frequent and important theme reported by the parents who participated in the study. Most of the participants believed psychological effects were the major group of negative effects that communication disorders had on the child’s family. These negative effects included: Touchy (tender-hearted) and hypersensitivity, impatient, anxiety, moodiness and sadness, guilt, fear, and helplessness. A large number of parents who participated in the study reported that impatient was one of the psychological problems they experienced: “My patience has been reduced, and I will lose my temper so fast,” (Fourth participant).

One parent who felt guilty about their child’s problem said “I always say, and last night I told a friend of mine who had just given birth. The children really should have their mothers by their side, but I was not with my child. My friend told me I quit my job and told them you did a good job,” (Sixth participant).

Anxiety about the future was also one of the negative psychological effects that were widely discussed by the participants. The remarks of two parents were as follows: “We are worried about his/her future because of his/her stuttering since there are also educated people around us who tell me that it is a pity that the child becomes an engineer or a doctor or have an important job and he cannot talk. We are getting so worried,” (Eighth participant). “She/he is three and a half years old now, but I am always worried about his/her future. Now she/he goes to kindergarten, children are less aware of her/his problems, but I am afraid that children will tell her/him at school (about her/his problems) and cause her/him frustration or loss of self-confidence,” (11th participant).

Economic effects

This theme was the least frequent theme reported by the participants. Parents who participated in the study reported that economic problems are another negative effect caused by children’s communication disorders. They reported that the high cost of speech therapy services for their children has caused many financial problems for them. one of the parents said “to treat my child’s stuttering, I have to take him to speech therapy two to three times a week. The high cost of speech therapy and the lack of insurance coverage for speech therapy have caused us a lot of financial problems,” (First participant).

Also, the parents believed that due to the high cost to the child with communication problems, they cannot afford to spend well on other activities for their child, such as sports classes, leisure, travel, and shopping clothes.

Family-dynamics effects

The participants believed that their child’s condition had negative influences on family-related aspects of their lives. Many parents reported the lack of time to take care of other family members, tensions between parents, reduced catching up with relatives and friends, migration to other cities, and reduced leisure time as the negative family dynamics effects caused by their children’s problems. “I cannot take care of my little one at all,” said one parent about the lack of time to take care of other family members,” (13th participant).

Another participant said of the tension between the parents: “His/her father did not feel responsible at all, he did not think about her/him, and I always argued with him about this issue and told him to follow up [the problem] until she/he was little, that he did not think at all,” (11th participant).

Another negative social effect expressed by the parents was the reduction of contact with relatives, one of the mothers said about this issue: “When we went somewhere (child’s name) he/she was bothered, we did less (we reduced the frequency of visiting) for his/her sake because he could not say anything and what he wanted to say,” (Fifth participant).

Job-educational effects

The parents frequently mentioned that their work and education, as the most important aspects of a person’s life, were under negative influences. This theme was extracted from the following categories: Mothers’ resignation, decrease in job quality, decrease in income, a lack of job promotion, restriction on continuing education, academic failure child’s sibling, and time restriction. Some of the parents’ statements in this regard were as follows:

“I have quit my job because of my son,” (Third participant).

“I go to the edge of being fired. There is a certain limit to taking leave and things get very double. Every time the kindergarten rings, I go to the kindergarten in a panic, which would not have happened if I had not been employed,” (First participant).

The ninth participant about the negative impact on his/her job and education and the lack of proper conditions to continue his/her education said: “Maybe if we didn’t have these problems, I would have continued my education or a proper job would have happened, but now I can’t because of the child’s problem.”

In summary, the content analysis revealed that the effects of children’s communication disorders could be classified into five different themes. The data analysis emerged themes and subthemes were sent to the parents who were willing to collaborate at this stage of the study to verify themes and subthemes. These findings and analysis were confirmed by the parents. While the research team searched for the core themes, supplemental or complementary themes did not come up.

Discussion

This study was conducted to explain the effects of children’s communication disorders on their parents’ QoL. According to the results of the present study, communication disorders in children can cause many negative effects on the parents’ QoL, including physical effects, psychological effects, economic effects, family-dynamic effects, and job-educational effects. The negative effects of children’s communication disorders on parents’ QoL were consistent with findings reported by the previous studies that investigated the QoL in parents of children with hearing loss [5], speech impairment [6], stuttering [8, 35], pervasive developmental disorders (autism and Asperger) [12, 27, 36], intellectual disability [37, 38], cerebral palsy [15, 16], and cancer [1]. However, what these studies reported were according to the common questionnaires of QoL such as SF-36 that led to a general understanding of the physical, emotional, mental, and well-being status of parents [6]. They could not provide a specific assessment of parents’ lives or perceptions. Thus, the overall picture (negative effect of child’s disorders on parents’ QoL) presented by this study came out similar to the pictures provided by the previous studies; however, the present study provided striking features of effects of child’s communication disorders on parents’ QoL. The in-depth, specific, and detailed findings of the current study could not be compared or achieved by the quantitative studies.

The physical and psychological problems that parents have raised concerns in this study and confirmed the findings of the previous studies have many negative effects on the parents’ QoL [12, 13, 38]. Parents who participated in the study experienced pain, physical disease, and excessive fatigue. Many trips in difficult conditions, such as hot weather to receive treatment sessions for children, the need to quickly perform personal activities for mothers, improper sleep, improper eating conditions, and numerous fatigues have caused physical problems for parents of children with communication disorders. Previous studies have examined the effects of a child’s speech impairment or stuttering on parents’ QoL but have not reported the types of physical problems in parents due to their child’s problem. Such finding is an artifact of the applied questionnaire which provided only a score and the researchers concluded that parents of children with speech impairment had lower scores in physical functioning subscales than parents of healthy children [5, 6]. Studies with a qualitative approach who recruited parents of children with cerebral palsy, autism spectrum disorders, and intellectual disabilities reported physical problems in line with the current study.

The other theme in the present study was the psychological effects. Parents of children with communication disorders reported touchy (tender-hearted) and hypersensitivity, impatient, concerns and worries, bad temper and discomfort, feeling guilty, helplessness, and fear as some of the most negative psychological problems due to their children’s problems. Some of these problems were reported by parents of children who stutter in the previous studies. Parents of children who stutter reported helplessness, frustration, anxiety, feeling guilt or self-blame, stress and worry [8, 35, 39]. The difference between this study and the studies on the effects of stuttering on parents’ QoL might be a consequence of the recruited participants, we interviewed parents of children with different types of communication disorders and they only focused on parents of children who stutter. Since all the interviewed parents in the present study mentioned psychological problems as the most important problems, the clinicians and researchers who are active in this field should consider the psychological problems in parents during the assessment and intervention properly, especially by SLPs. In a study conducted in Sri Lanka, parents of children who stutter reported that they had not received proper attention from SLPs regarding their psychological and emotional problems [35].

The other theme in the present study about the negative effects of a child’s communication disorder on parents’ QoL was economic problems. This economic problem was reported in the previous studies that investigated the effects of children’s stuttering on parents’ lives [39]. Such economic problems may look familiar for all disorders or diseases, but it highlights the need for special and comprehensive attention from the related agencies which could be the governments’ organizations or private companies. In this case, providing complementary and private insurance as well as services and support from public health organizations would be deeply valued. Additionally, the obstacles of insurance support for rehabilitation services, especially for speech-language pathology services, should be removed to reduce the burden on parents during the process of assessment and intervention for their children’s communication disorders [38].

The negative job-educational effects reported by parents in this study and previous studies with a focus on the effect of cerebral palsy [15, 16] were similar. Whereas, the nature of communication disorders is not similar to the nature of cerebral palsy, finding such effects may show how depth a communication disorder would affect. Such job-educational effects of communication disorder have not been reported by the previous studies that recruited children with speech or language impairments.

One of the outstanding results of the present study was the negative effects of a child’s communication disorder on the “family dynamics.” This finding confirms the pervasive nature of communication disorder on parents’ QoL, an aspect that previous studies did not mention or report. In this case, the child’s communication disorders have negative effects on parents’ interactions, their roles, and relationships with other kids, relatives, and friends. They reported how the child’s communication disorder reduced their opportunity to have leisure activities or time. Family dynamics is the primary source of relationship security or stress (since family members support each other emotionally, physically, and financially) [40] and the present study showed how this primary source was affected by the child’s communication disorder. When the family relationship is stressful instead of secure, the home environment would be troubled with arguments, endless critical comments/reactions, and onerous demands [40, 41]. Affected family dynamics would influence the health and recovery outcomes, and have enough values to be considered in clinical settings. When the family dynamics do not work properly, it may cause a child to experience adverse childhood trauma (stress and trauma) as he/she grows up. Studies have indicated that adverse childhood trauma is connected to an intensified risk of emerging physical and mental health issues [41, 42]. Therefore, we may be able to conclude that there is a cycle between a child’s communication disorder, family dynamics, and negative childhood experience, although further studies warranted exploring such a relationship.

The present study confirmed and extended the findings of the previous studies that showed how communication disorder in a child could negatively affect the QoL of parents, and emphasized the highly threatening nature of these disorders on parents’ lives. The present study provided supportive documents on how the families of children with communication disorders need to receive special attention from private and public health systems to be able to elevate their QoL. Using social workers and counselors with proper knowledge and experience in this field and their presence in the rehabilitation team can be useful in improving the families’ living conditions [38].

Future studies may use the findings of the present study to develop a questionnaire or scale to assess the caregiver burdens or QoL among parents who have children with communication disorders. This study took the first step in developing new questionnaires or scales with a qualitative design. It could find the main concepts related to the studies concerned about the effects of communication disorders on parents. Even, the extracted themes, subthemes, and codes in the current study can be used to define the subcategories and primary items of the related questionnaires. Meanwhile, in making new questionnaires and scales, the researchers should add up the findings of the interviews with a review of the literature (two important sources for item generation).

Conclusion

The current study explained the negative effects of communication disorders on children on parents’ QoL with a qualitative research design. According to parents’ reports, communication disorders in children can cause several negative effects on parents’ life included physical, psychological, economic, social-communication, and job-educational effects. These negative effects justify the need to provide more support for the children’s family as well as more attention to the parent’s QoL. These results can be useful for policymakers, researchers, and service providers in the field of assessment and treatment of communication disorders. It is better that future studies can investigate the parents’ QoL with quantitative methods to generalize the results of the present study. Moreover, the findings of the current study can be used for the development of new instruments for measuring caregiver burden and QoL among parents of children with communication disorders and their parents.

Study limitation

The generalization of our findings is limited because of some issues. The number of fathers who participated was not comparable to the number of mothers. Replicating this study with a sample that included more fathers might reach to different perspective about the effects of communication disorders in children on parents’ QoL. Data collection and interviews with parents were performed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the effects of the pandemic situation on peoples’ lives should be considered. Since the data was collected by interview in a qualitative study, participants’ abilities to talk about their problems and their assertiveness in this case might have some effects. According to Grice’s cooperative principles, those people who consider quantity, quality, relation, and manner to provide information would decrease the language implicature during a conversation or interview. Thus, participants who talk more about the subject under study comment on various topics, and present several examples would increase the comprehensiveness and depth of the information.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research approved by the Ethical Committee of Semnan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.-UMS.REC.1397.279).

Funding

This article is financially supported by the Student Research Committee in Semnan University of Medical Sciences (Grant No.: 1377).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and writing the original draft: Banafshe Mansuri, Seyed Abolfazl Tohidast and Masoomeh Salmani; Methodology: Seyed Abolfazl Tohidast and Banafshe Mansuri; Investigation: Rezvaneh Nahidi and Seyed Abolfazl Tohidast; Funding acquisition: Rezvaneh Nahidi and Seyed Abolfazl Tohidast; Review and Editing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

All the researchers of this study wish to thank the Vice Chancellor for Research of the Semnan University of Medical Sciences as well as its staff and families of children with communication disorders who participated in the study.

References

- Sajjadi H, Roshanfekr P, Asangari B, Zeinali Maraghe M, Gharai N, Torabi F. [Quality of life and satisfaction with services in caregivers of children with cancer (Persian)]. Iran Journal of Nursing. 2011; 24(72):8-17. [Link]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHOQOL-BREF: Introduction, administration, scoring and generic version of the assessment: Field trial version, December 1996. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1996. [Link]

- Gellatly J, Bee P, Kolade A, Hunter D, Gega L, Callender C, et al. Developing an intervention to improve the health related quality of life in children and young people with serious parental mental illness. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2019; 10:155. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00155] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Pelchat D, Bisson J, Ricard N, Perreault M, Bouchard JM. Longitudinal effects of an early family intervention programme on the adaptation of parents of children with a disability. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 1999; 36(6):465-77. [DOI:10.1016/S0020-7489(99)00047-4] [PMID]

- Aras I, Stevanović R, Vlahović S, Stevanović S, Kolarić B, Kondić L. Health related quality of life in parents of children with speech and hearing impairment. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2014; 78(2):323-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.12.001] [PMID]

- Rudolph M, Kummer P, Eysholdt U, Rosanowski F. Quality of life in mothers of speech impaired children. Logopedics, Phoniatrics, Vocology. 2005; 30(1):3-8. [DOI:10.1080/14015430410022292] [PMID]

- Wake M, Hughes EK, Collins CM, Poulakis Z. Parent-reported health-related quality of life in children with congenital hearing loss: A population study. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2004; 4(5):411-7. [DOI:10.1367/A03-191R.1] [PMID]

- Langevin M, Packman A, Onslow M. Parent perceptions of the impact of stuttering on their preschoolers and themselves. Journal of Communication Disorders. 2010; 43(5):407-23. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcomdis.2010.05.003] [PMID]

- Limm H, von Suchodoletz W. [Perception of stress by mothers of children with language development disorders (German)]. Praxis der Kinderpsychologie und Kinderpsychiatrie. 1998; 47(8):541-51. [PMID]

- Khanna R, Madhavan SS, Smith MJ, Patrick JH, Tworek C, Becker-Cottrill B. Assessment of health-related quality of life among primary caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2011; 41(9):1214-27. [DOI:10.1007/s10803-010-1140-6] [PMID]

- McStay RL, Trembath D, Dissanayake C. Stress and family quality of life in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: Parent gender and the double ABCX model. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2014; 44(12):3101-18. [DOI:10.1007/s10803-014-2178-7] [PMID]

- Allik H, Larsson JO, Smedje H. Health-related quality of life in parents of school-age children with asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2006; 4:1. [DOI:10.1186/1477-7525-4-1] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Vasilopoulou E, Nisbet J. The quality of life of parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2016; 23:36-49. [DOI:10.1016/j.rasd.2015.11.008]

- Lee GK, Lopata C, Volker MA, Thomeer ML, Nida RE, Toomey JA, et al. Health-related quality of life of parents of children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2009; 24(4):227-39. [DOI:10.1177/1088357609347371]

- Okurowska-Zawada B, Kulak W, Wojtkowski J, Sienkiewicz D, Paszko-Patej G. Quality of life of parents of children with cerebral palsy. Progress in Health Sciences. 2011; 1(1):116-24. [Link]

- Lee MH, Matthews AK, Park C. Determinants of health-related quality of life among mothers of children with cerebral palsy. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2019; 44:1-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2018.10.001] [PMID]

- Salehpoor A, Latifi Z, Tohidast SA. Evaluating parents' reactions to Children's stuttering using a Persian version of reaction to Speech Disfluency Scale. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2020; 134:110076. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijporl.2020.110076] [PMID]

- Ying K, Rostenberghe HV, Kuan G, Mohd Yusoff MHA, Ali SH, Yaacob NS. Health-related quality of life and family functioning of primary caregivers of children with cerebral palsy in Malaysia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(5):2351. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18052351] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Wijesinghe CJ, Fonseka P, Hewage CG. The development and validation of an instrument to assess caregiver burden in cerebral palsy: Caregiver difficulties scale. The Ceylon Medical Journal. 2013; 58(4):162-7. [DOI:10.4038/cmj.v58i4.5617] [PMID]

- Savari K, Naseri M, Savari Y. Evaluating the role of perceived stress, social support, and resilience in predicting the quality of life among the parents of disabled children. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education. 2021; 70(5):644-58. [DOI:10.1080/1034912X.2021.1901862]

- Barker DH, Quittner AL, Fink NE, Eisenberg LS, Tobey EA, Niparko JK, et al. Predicting behavior problems in deaf and hearing children: the influences of language, attention, and parent-child communication. Development and Psychopathology. 2009; 21(2):373-92. [DOI:10.1017/S0954579409000212] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Le HN, Mensah F, Eadie P, Sciberras E, Bavin EL, Reilly S, et al. Health-related quality of life of caregivers of children with low language: Results from two Australian population-based studies. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2022; 24(4):352-61. [DOI:10.1080/17549507.2021.1976836] [PMID]

- Okurowska-Zawada B, Wojtkowski J, Kułak W. Quality of life of mothers of children with myelomeningocele. Pediatria Polska. 2013; 88(3):241-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.pepo.2013.02.001]