Volume 22, Issue 2 (June 2024)

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2024, 22(2): 151-166 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Bidari S, Ghorbani F, Barati K, Jalaleddini A, Pourahmadi M. The Role of Non-rigid Pelvic Belts in Managing Pregnancy-related Pelvic Girdle Pain and Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2024; 22 (2) :151-166

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1879-en.html

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1879-en.html

Shahrbanoo Bidari1

, Faezeh Ghorbani *2

, Faezeh Ghorbani *2

, Kourosh Barati1

, Kourosh Barati1

, Arman Jalaleddini3

, Arman Jalaleddini3

, Mohammadreza Pourahmadi4

, Mohammadreza Pourahmadi4

, Faezeh Ghorbani *2

, Faezeh Ghorbani *2

, Kourosh Barati1

, Kourosh Barati1

, Arman Jalaleddini3

, Arman Jalaleddini3

, Mohammadreza Pourahmadi4

, Mohammadreza Pourahmadi4

1- Department of Orthotics and Prosthetics, School of Paramedical and Rehabilitation Sciences., Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran.

2- Department of Orthotics and Prosthetics, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, Rafsanjan, Iran.

4- Department of Physiotherapy, Rehabilitation Research Center, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Orthotics and Prosthetics, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, Rafsanjan, Iran.

4- Department of Physiotherapy, Rehabilitation Research Center, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 1474 kb]

(3201 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4500 Views)

Full-Text: (2842 Views)

Introduction

Pelvic girdle pain (PGP) and low back pain (LBP) related to pregnancy are women’s concerns and common social challenges. According to the literature, about 30% to 78% of women suffer from an amount of PGP (deep, diffusing, irradiating, or radiating pain around the sacroiliac joint or symphysis pubis) or LBP during pregnancy or after three months post-partum [1-5]. This has been reported at a severe level in one-third of women [6]. PGP might affect sitting, walking, and standing ability leading to disability in daily activity, and is estimated as the reason for 37% of sick leaves during pregnancy [6-10]. The symptoms can be disabling, not necessarily removed after childbirth, and often later. Despite the negative effect on the quality of life, the reason for pain in pregnancy has been recognized weakly [11]. This reasonably common disorder involves hormonal fluctuations, genes and biomechanical reasons [12]. A history of LBP, pelvic injury, young age, and multiplication are raised as pregnancy-related LBP and PGP risk factors [13, 14].

According to a theoretical model of pelvic function, in the self-locking mechanism, shear force in the sacroiliac joint is prevented through augmenting friction by using two factors as follows: The particular anatomical alignment, which increases friction coefficient (form-closure), and the tension of muscles and ligaments, which cross sacroiliac joint (SIJ) and provide higher stiffness (force-closure) [15, 16]. It has been recommended that during pregnancy, hormonal (rise of fertility hormones or hormones related to parturition), mechanical factors (lengthening of pelvic joints ligaments and fascia) and changes in motor control, cause pelvic instability and consequently lead to PGP [8, 17-20]. For this reason, most treatments for PGP are based on intervention approaches that improve muscle functions and pelvic stiffness [21]. Literature has proven that multimodal interventions, including physiotherapy, pelvic belt, and supplementary interventions (ergonomic education, massage therapy, acupuncture, and yoga), are effective in LBP and PGP relief [3, 22-30]. A Cochrane review indicated the superiority of using a belt or acupuncture, physical therapy, and exercise over only taking care. However, the best treatment options are not consensually declared [25].

Pelvic belts are used to treat pelvic pain during pregnancy and postpartum. The logic for using belts is stabilizing and compressing SIJ surfaces and providing pelvic girdle stability through increasing force-closure (applying external force) [31, 32]. By this mechanism, pelvic belts might provide enough support for symphysis pubis and SIJ pain-relieving and are proposed as a primary treatment [33, 34]. Existing studies regarding the effects of wearing soft belts on pain relief have some limitations that make it difficult to decide whether to use soft belts for clinical applications. First of all, the exact effects of wearing a pelvic belt on pain reduction are controversial. Ostgaard et al. indicated that 83% of PGP or LBP women reported posterior pelvic pain reduction while wearing a pelvic belt [33]. However, other studies did not report any pain-relieving after pelvic belt use [35]. Secondly, the pure effect of pelvic belts is difficult to specify, as they are used in combination with other treatments such as exercise and acupuncture. Thirdly, different belts are used [29, 31, 35, 36] and the best type regarding symptom relief and patient tolerance has not been specified yet.

Furthermore, a pelvic belt is used in clinical applications and other treatments, such as exercise and acupuncture. Therefore, their pure effect is not specified. Moreover, different belts are used [29, 31, 35, 36] and the best type regarding symptom relief and patient tolerance has not been specified yet. Some researchers investigated the effect of different positions (high position in anterior superior iliac spine level and low position in greater trochanter level and pubis joint) [31, 37] and flexibility (rigid and flexible) of the belt [37, 38] and different amounts of compressive force (50 and 100 N) [39] using biomechanical models. Two systematic reviews in 2019 indicated the positive effect of using dynamic elastomeric fabric orthosis or maternity support garments on pain and function during the pre-natal period [40, 41]. However, adherence to the principle of comprehensiveness (encompassing gray literature) and adherence to the principle of quality is missed in older systematic reviews. Moreover, the previous reviews considered different evidence levels. Therefore, to the best of our knowledge, a lack of consistent and citable evidence is considered regarding the exact effect of pelvic belts on pregnancy-related PGP and LBP. Accordingly, the current study reviews level II literature (randomized control trials or control trials) considering pelvic belt efficacy on pain, improves function in pregnant women with PGP and LBP, and provides a practical and clinical recommendation regarding the ability of pelvic belt prescription in pregnant women, and suggests when to use a pelvic belt during pregnancy.

Materials and Methods

This study was developed based on the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses principles.

Search strategy

Two reviewers independently performed a computerized literature search from PubMed/MEDLINE (NLM), Scopus, Web of Science, PEDro and Google Scholar. The key terms used in PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science and Scopus included the following items: ([Pelvic AND pain*] OR [pelvic girdle AND pain*] OR [pelvic AND girdle pain*] OR [symphysis pubis AND dysfunction*] OR [pubis dysfunction* AND symphysis]) AND ([pregnant* AND woman*] OR [pregnant*] OR [gestation*]) AND ([brace*] OR [belt*] OR [semirigid AND belt*] OR [nonrigid AND belt*] OR [maternity AND garment*] OR [pelvic AND belt*) OR [soft AND belt*]OR [support AND garment*] OR [pelvic support AND belts*] NOT [seat AND belt*]).

Study selection

Eligibility criteria

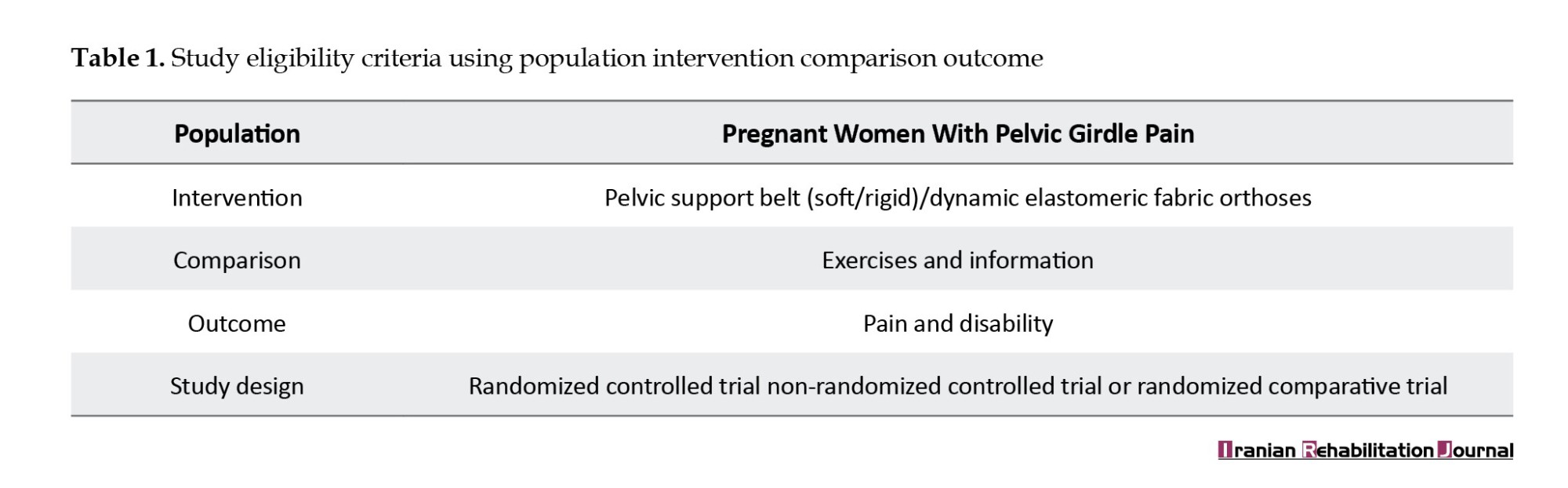

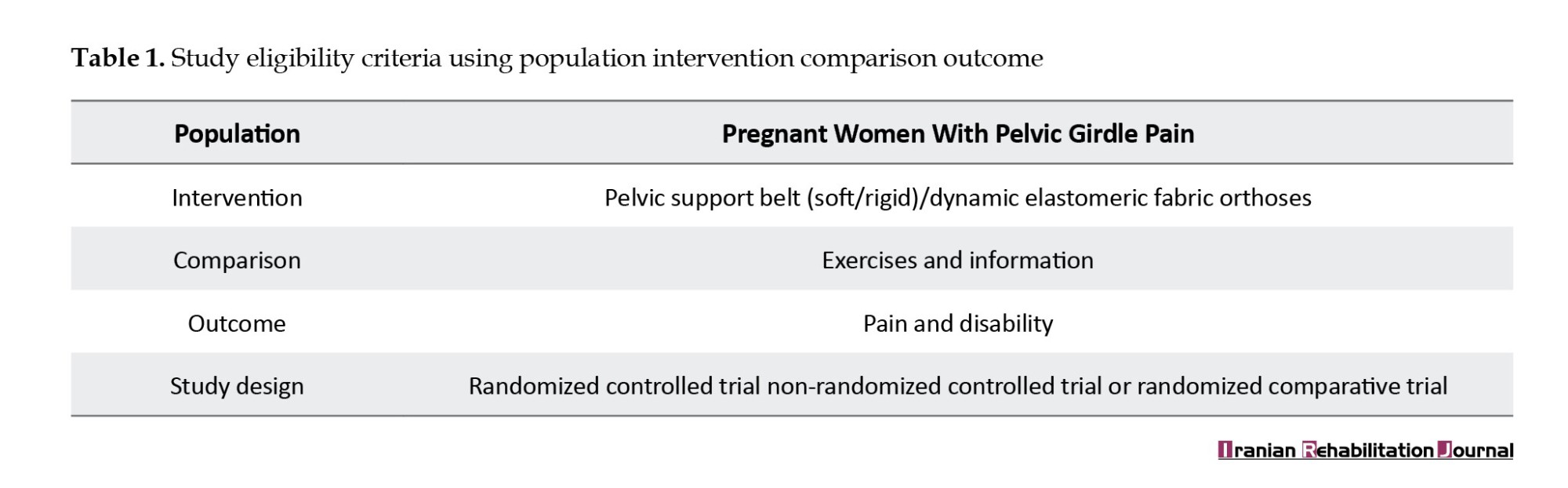

Table 1 provides details on study eligibility criteria using the population, intervention, comparison, outcome, and study design framework.

Selection procedure

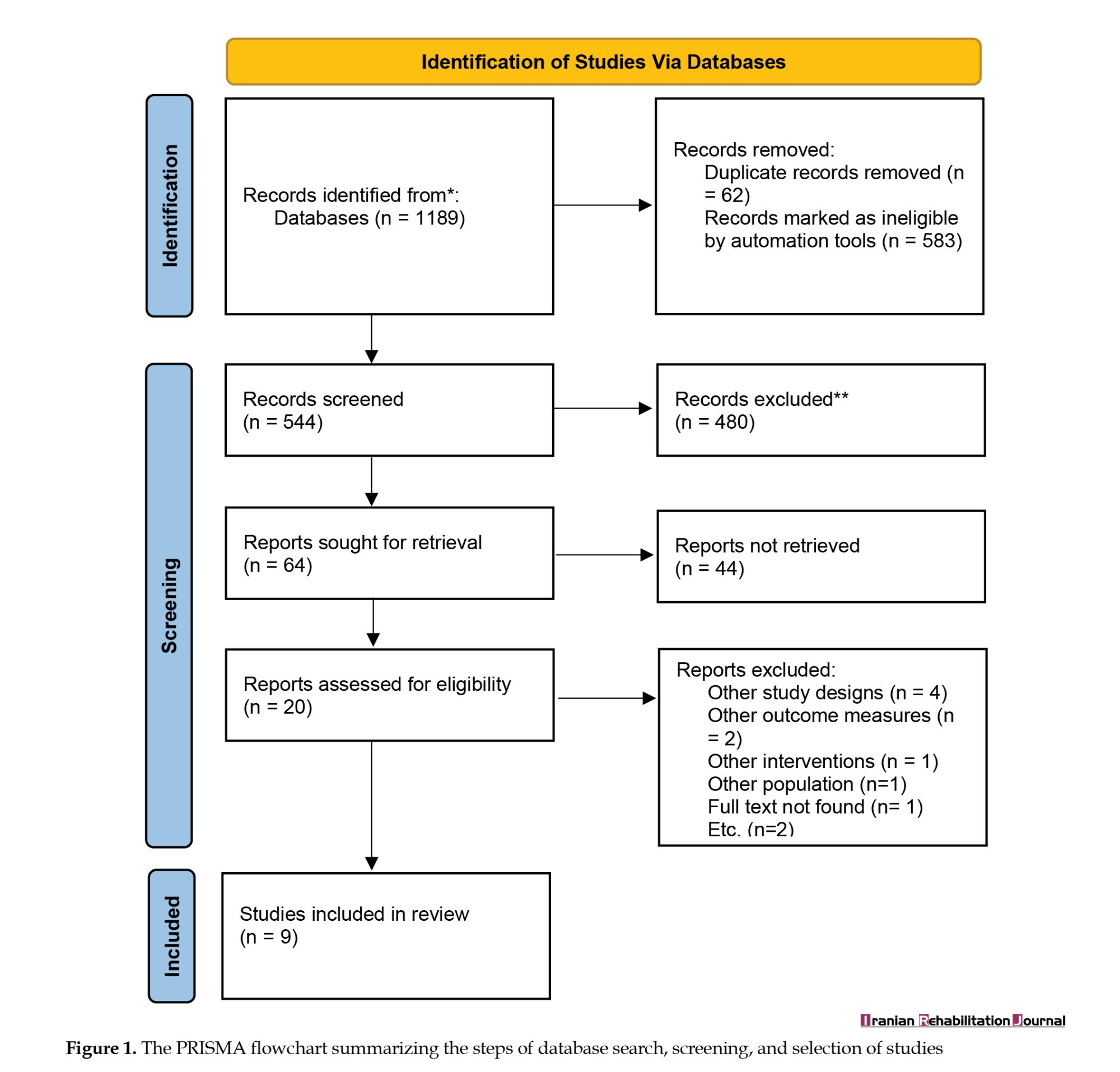

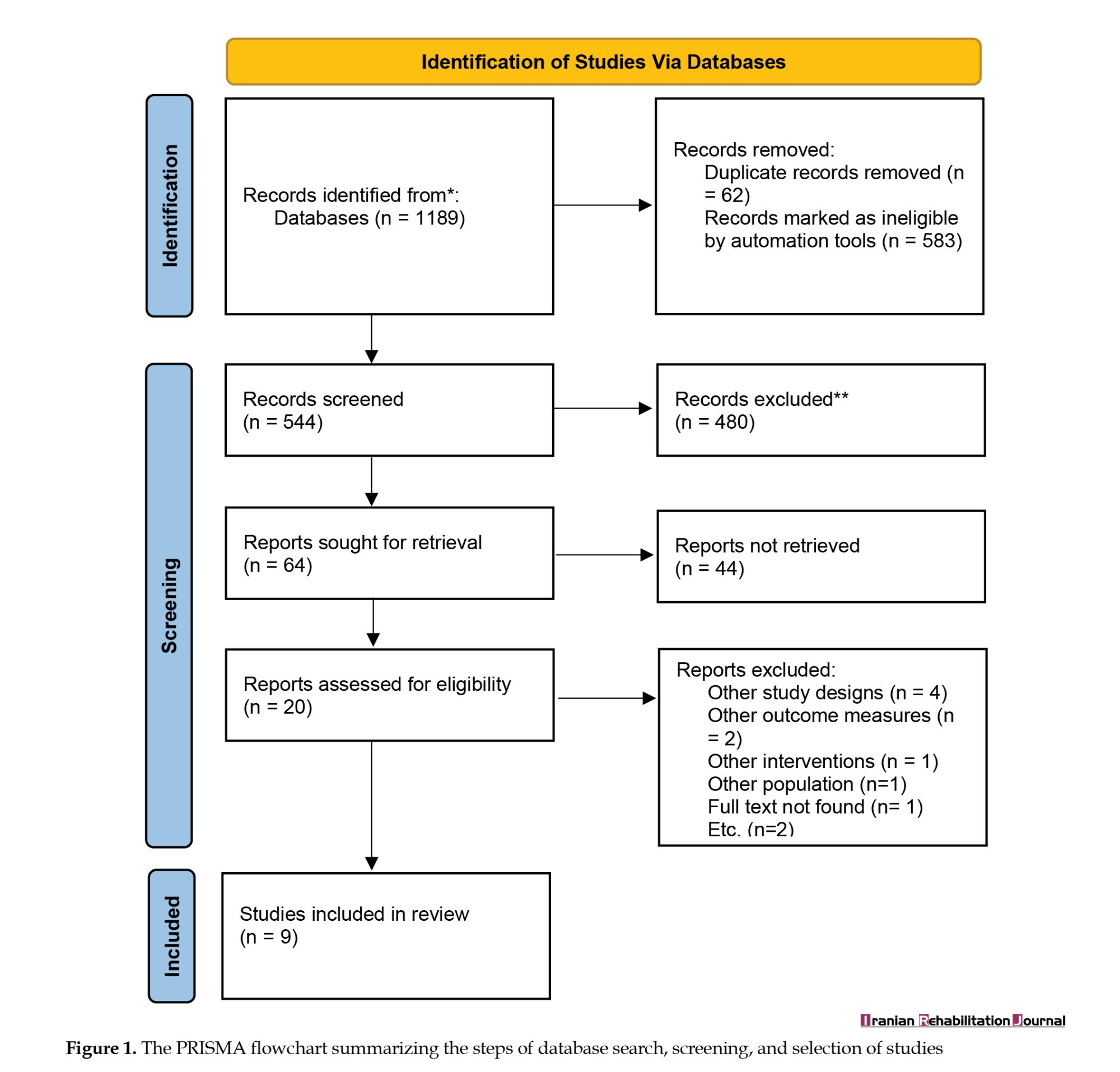

The review included studies in which pregnant women with PGP used a pelvic belt or pelvic supports to relieve pain. Experimental studies, including randomized controlled trials, non-randomized controlled trials (allocation performed with the date of birth, alteration or record numbers) or randomized comparative trials, were considered for this review. The review only included the studies published within 21 years (April 2000 to April 2021), published in peer-reviewed journals, full-text articles, and written in English. Two independent researchers (SB/FG) evaluated the identified studies for eligibility by screening the title and abstract, and then the full texts, grading each study as eligible/not eligible/might be eligible at each stage. Included studies were agreed upon by the two reviewers (SB/FG) and in case of disagreement, a third reviewer (MPA) mediated. The details, including sample size, intervention type, duration, and outcome measures, were extracted from the articles. The full texts of selected studies were obtained, and then two reviewers appraised the studies independently and scored them based on 11 points on the PeDro scale. A third collaborator resolved any disagreements in selecting the studies and scoring them. The complete process of study selection is summarized in the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses principles flow diagram (Figure 1).

Data extraction

The researchers extracted the data, which was then rechecked by a third reviewer. As data were missing or ambiguous, trial authors were contacted for additional data.

The following information was extracted: Trial authors, countries, study design, the week of pregnancy, sample size, interventions, type of belt, study setting, outcome measures, follow-up period, and main results. Data related to crucial outcome measures, including pain and disability, were extracted.

Quality assessment in individual trials

The two reviewers (SB/FG) underwent training and conducted a pilot quality assessment. They evaluated the quality of each included trial independently, using the PeDro quality assessment tool informed by empirical evidence to assess internal validity. The third reviewer (MPA) commented on the following discussion for any disagreement. Each quality component was reported as low, fair, or high quality in tabular form.

Results

A total of 1188 studies were identified during the search across different databases. Additionally, a hand search of references provided in studies yielded one more study. After removing duplicates of different databases and records marked as ineligible by automation tools, 544 articles remained. Upon initial review, the titles and abstracts of the articles were reviewed and 64 articles were selected for more surveys. In the next step, the full text of the articles was carefully reviewed, and 55 articles were excluded based on predetermined criteria. Nine articles met the inclusion criteria and were selected for the systematic review (Figure 1).

Quality of included studies

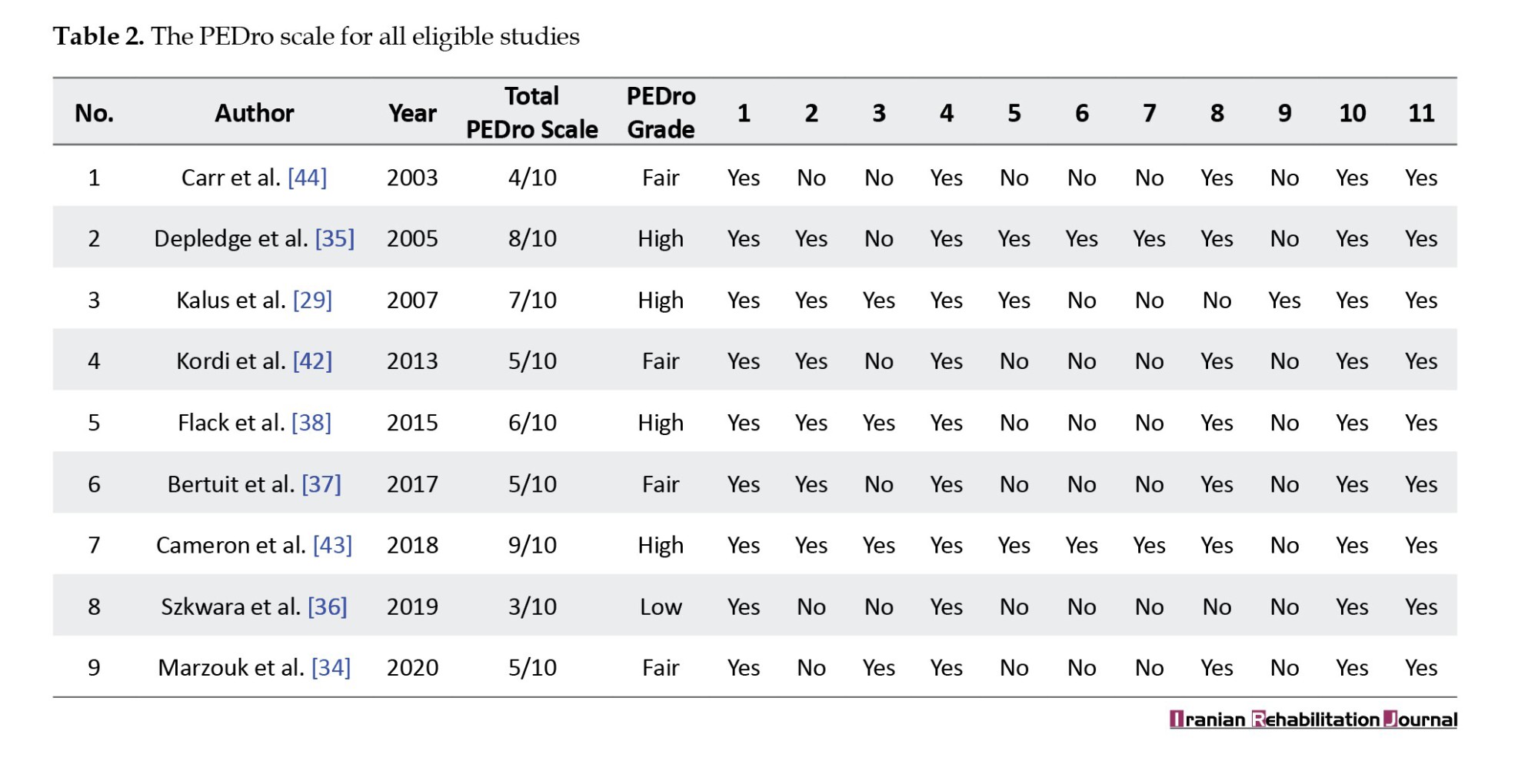

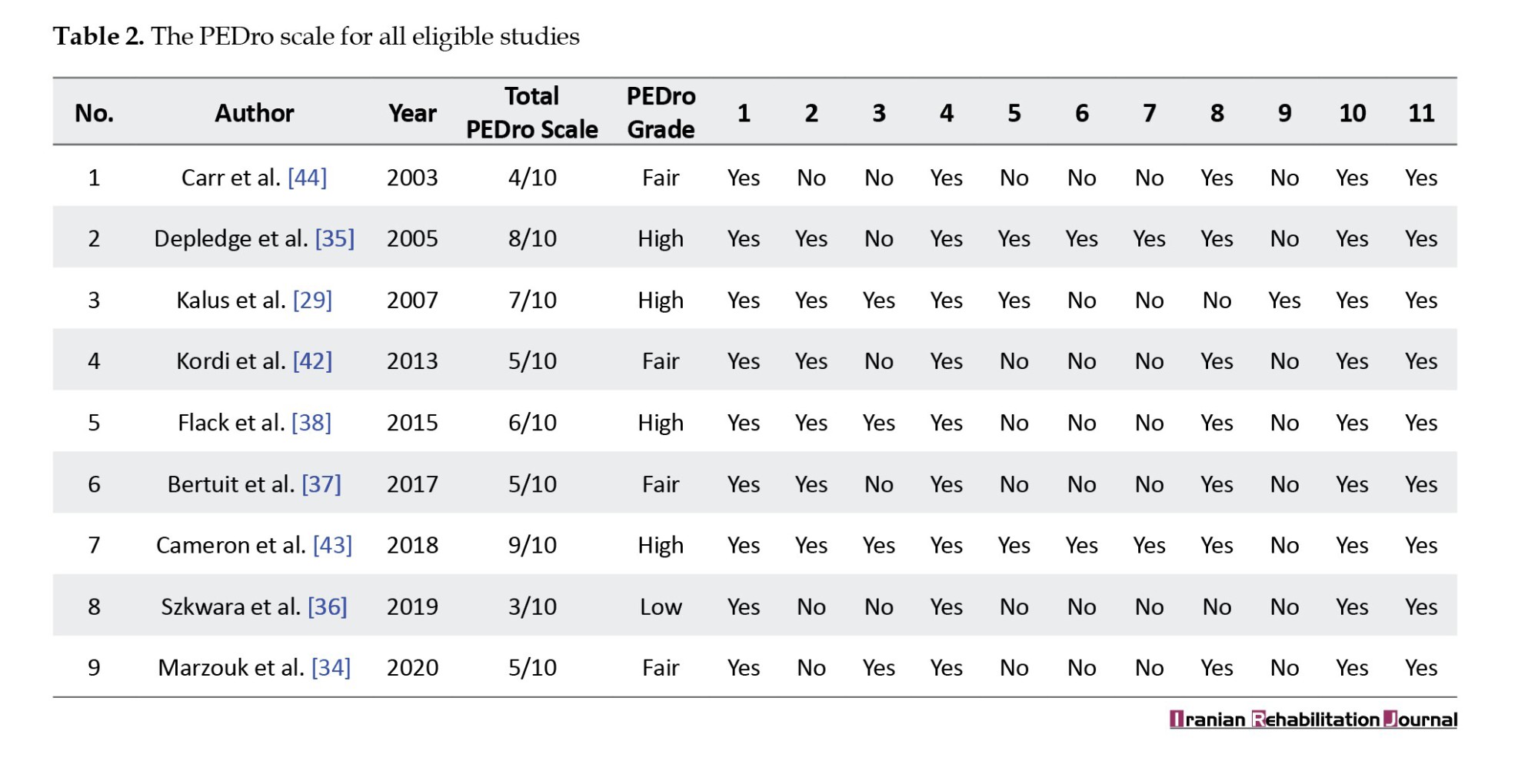

The quality was considered for all studies. One study was rated as low quality, four were rated as fair quality, and four were rated as high quality. Table 2 shows the quality of the included studies.

Review of participant characteristics

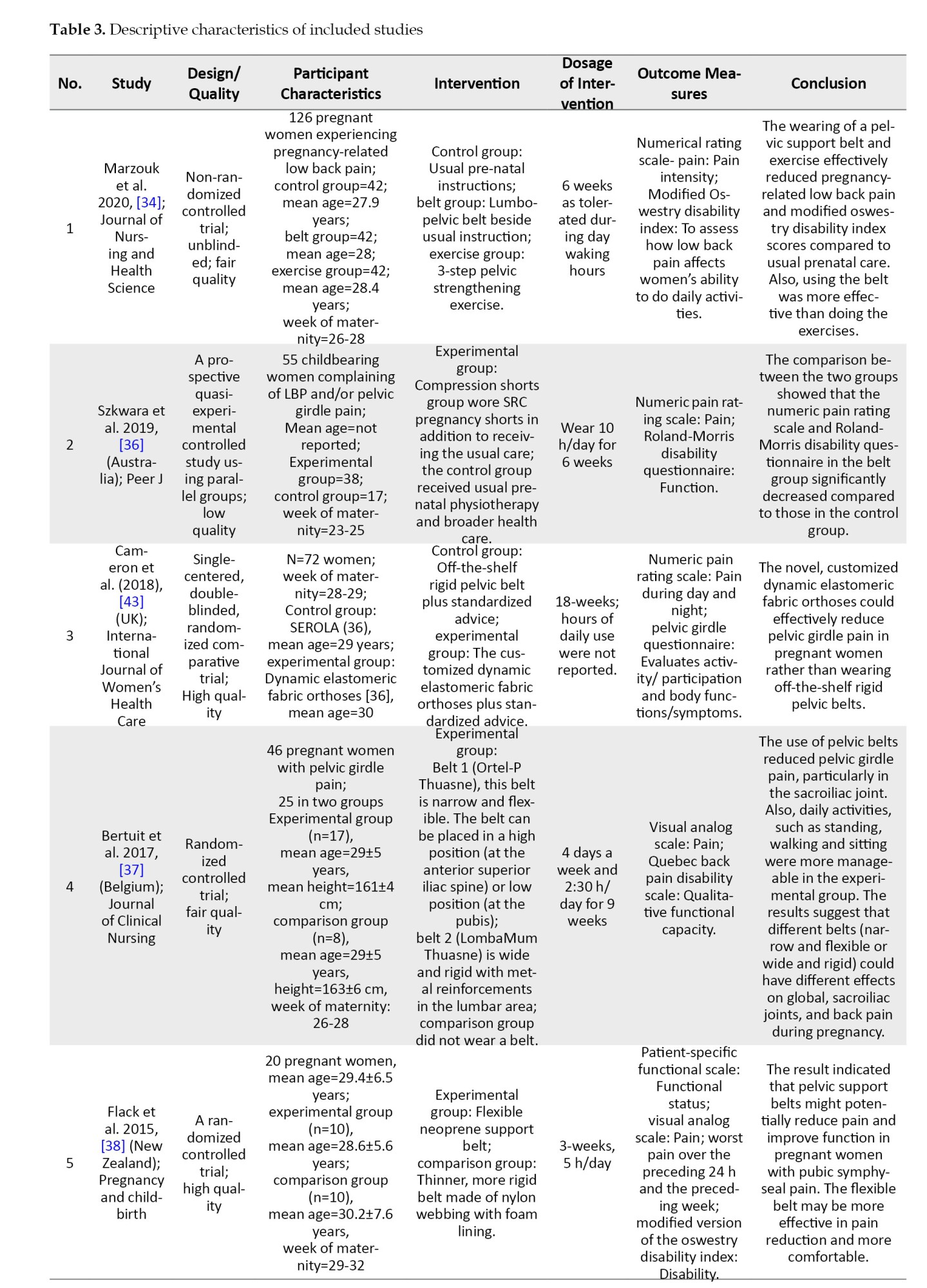

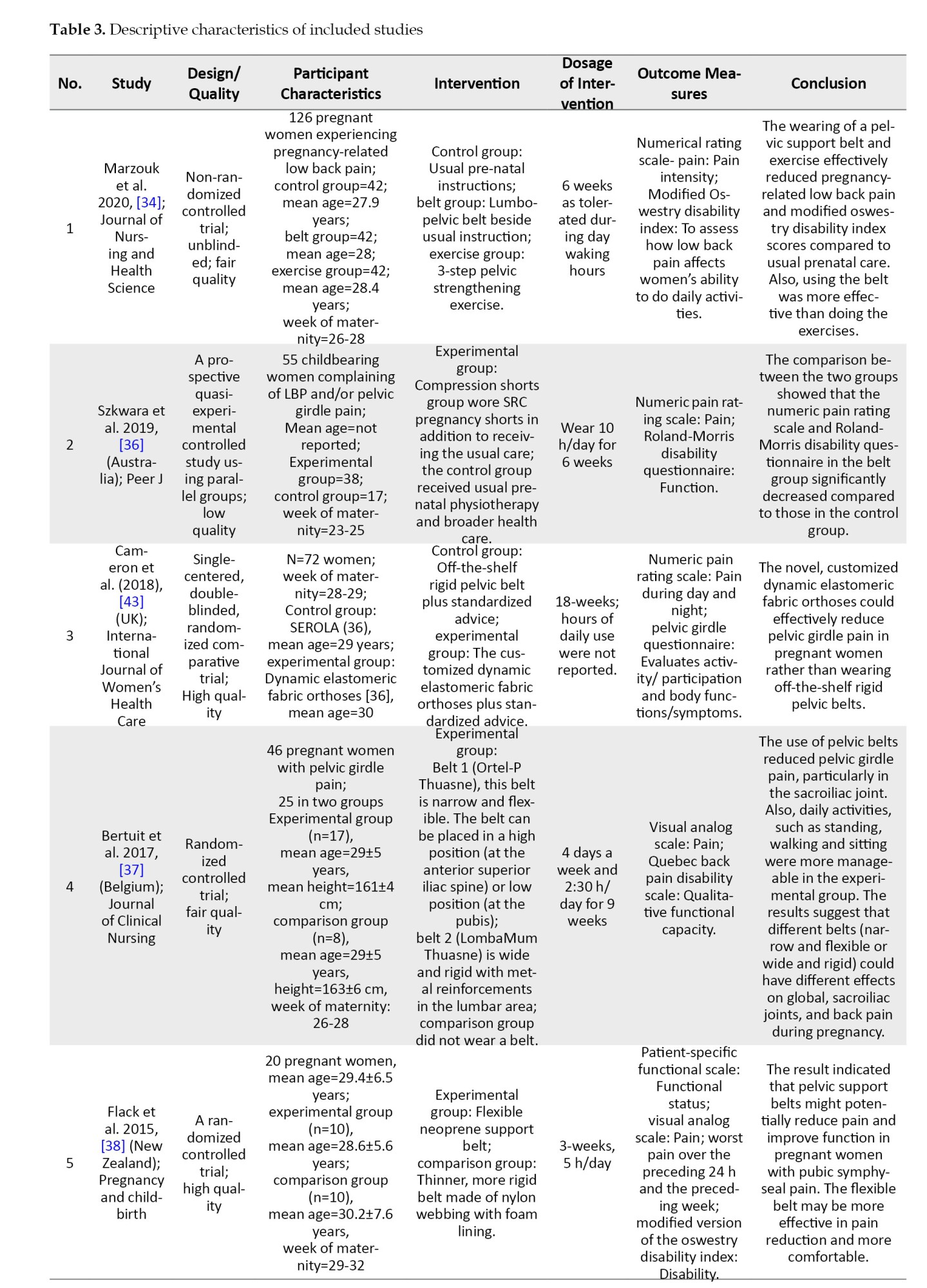

Table 3 shows eligible trial population characteristics. According to the included studies, PGP is described as pain in the symphysis pubis or SIJ in pregnant women [34-38, 42, 43]. Two studies from New Zealand considered symphysis pubis [35, 38]. One study from Belgium [37] and one from the United Kingdom [43] considered SIJ or symphysis pubis. One study from Iran considered SIJ [42]. One study from Egypt and one from Australia considered lumbar spine or posterior pelvic pain [34, 36], one from the USA considered LBP [44] and one study from Australia considered two types of bra [29]. All of the studies considered pregnant women and the mean age ranged between 26.72 and 30. Two studies did not report the mean age of the included participants [29, 36]. The study by Flack et al. justified the compared groups for patient-specific functional scale pre-intervention [38]. At the start of the intervention, the gestational age was between the 23rd and 32nd weeks of maternity. Szkwara et al. started the intervention at the earliest time (23th-25th week) [36] and Depledge et al. and Flack et al. started the intervention at a mean age of 31st gestational week [35, 38].

Methodology considered and outcome measures

Nine papers that met the inclusion criteria were evaluated. Two studies were performed in a quasi-experimental design (controlled trials) [34, 36] and three studies were randomized comparative trials that compared the efficacy of two types of maternity support [29, 38, 43]. Four studies were performed in randomized control trials design [35, 37, 42, 44]. In four studies [35, 37, 38, 43], both types of non-rigid and rigid pelvic support were evaluated, and five studies evaluated the therapeutic effect of the non-rigid belt as an intervention [29, 34, 36, 42, 44]. As a result, the team decided to consider the results of the non-rigid pelvic support for systematic review.

The pain was measured using the visual analog scale [29, 37, 38, 42] or the numeric pain rating scale [34-36, 43], or the pain in pregnancy questionnaire [44]. Disability was measured using the Oswestry disability index [42], a modified version of the oswestry disability index [34, 38], the patient-specific functional scale [35, 38], the Quebec back pain disability scale [37], the Roland Morris disability questionnaire [35, 36], the pelvic girdle questionnaire [43] or a Likert scale [29, 44]. Pain and disability were evaluated as the primary outcome measures.

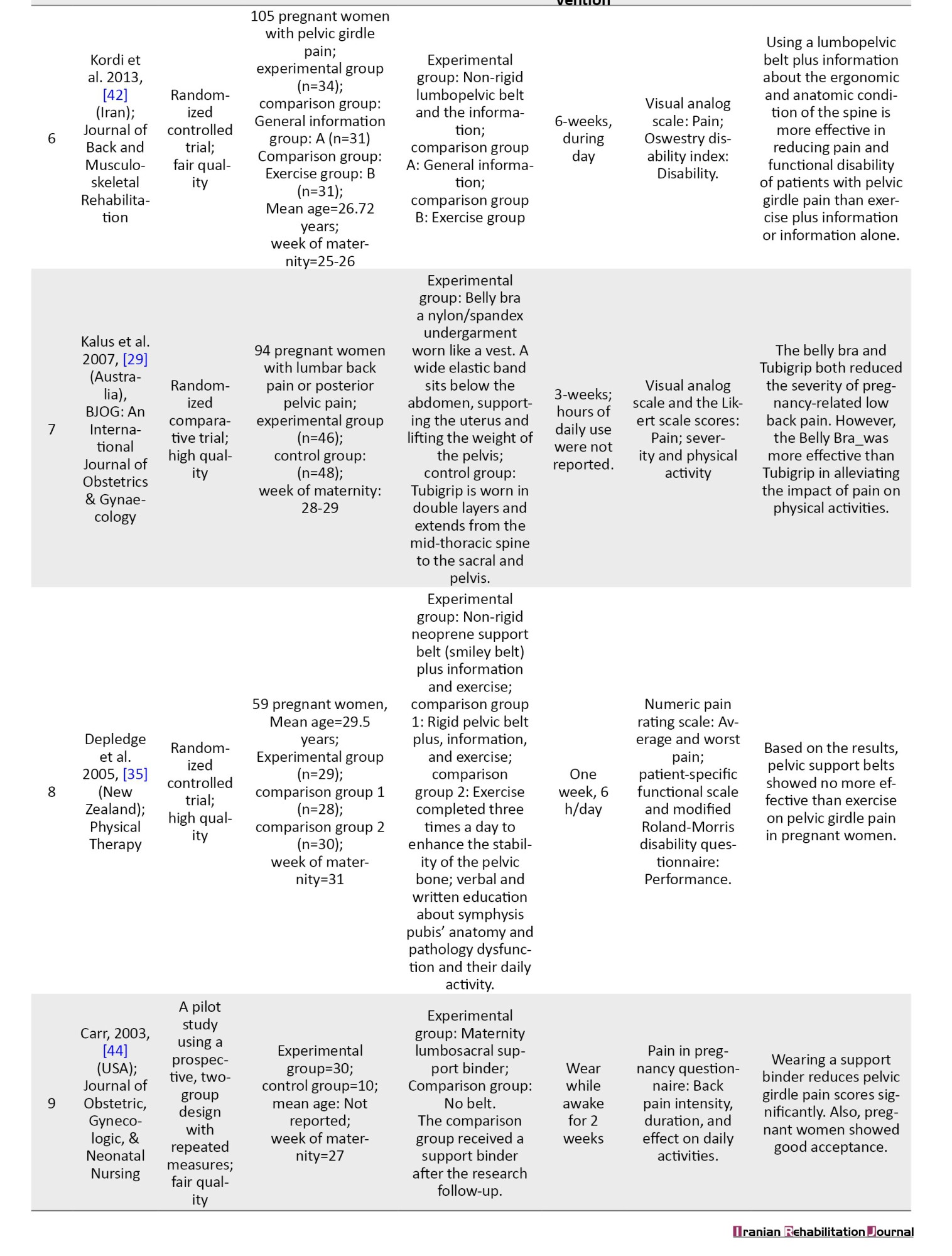

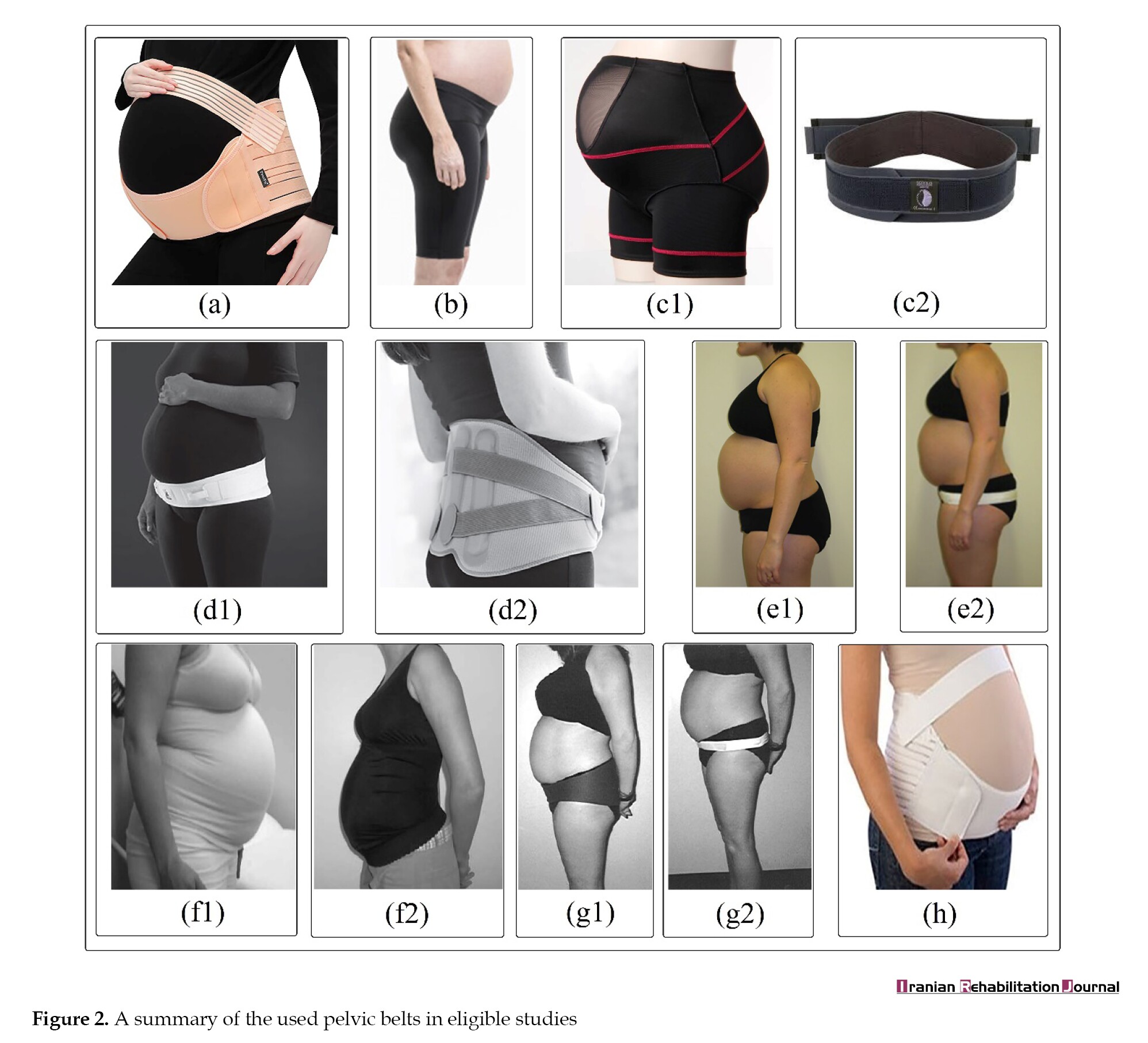

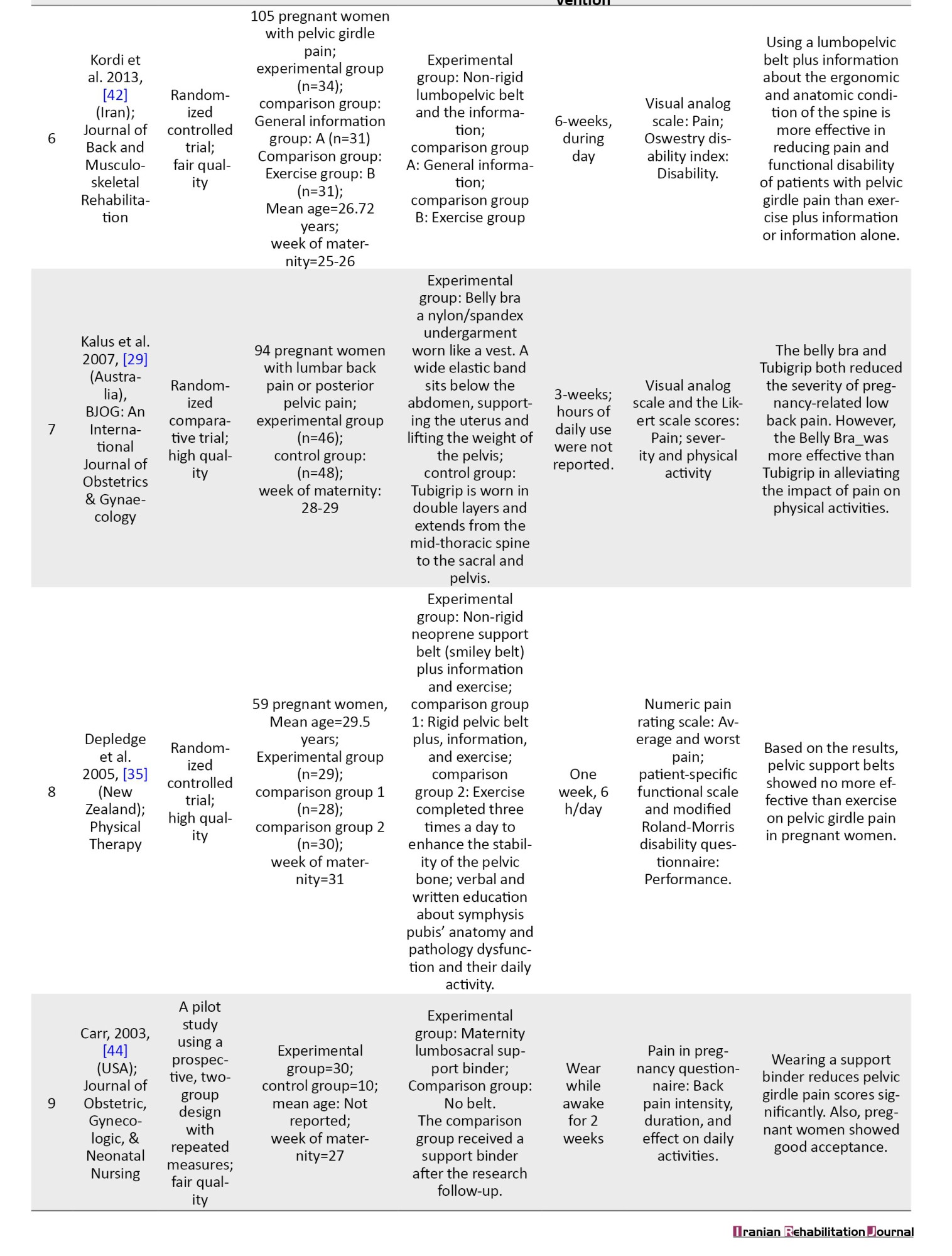

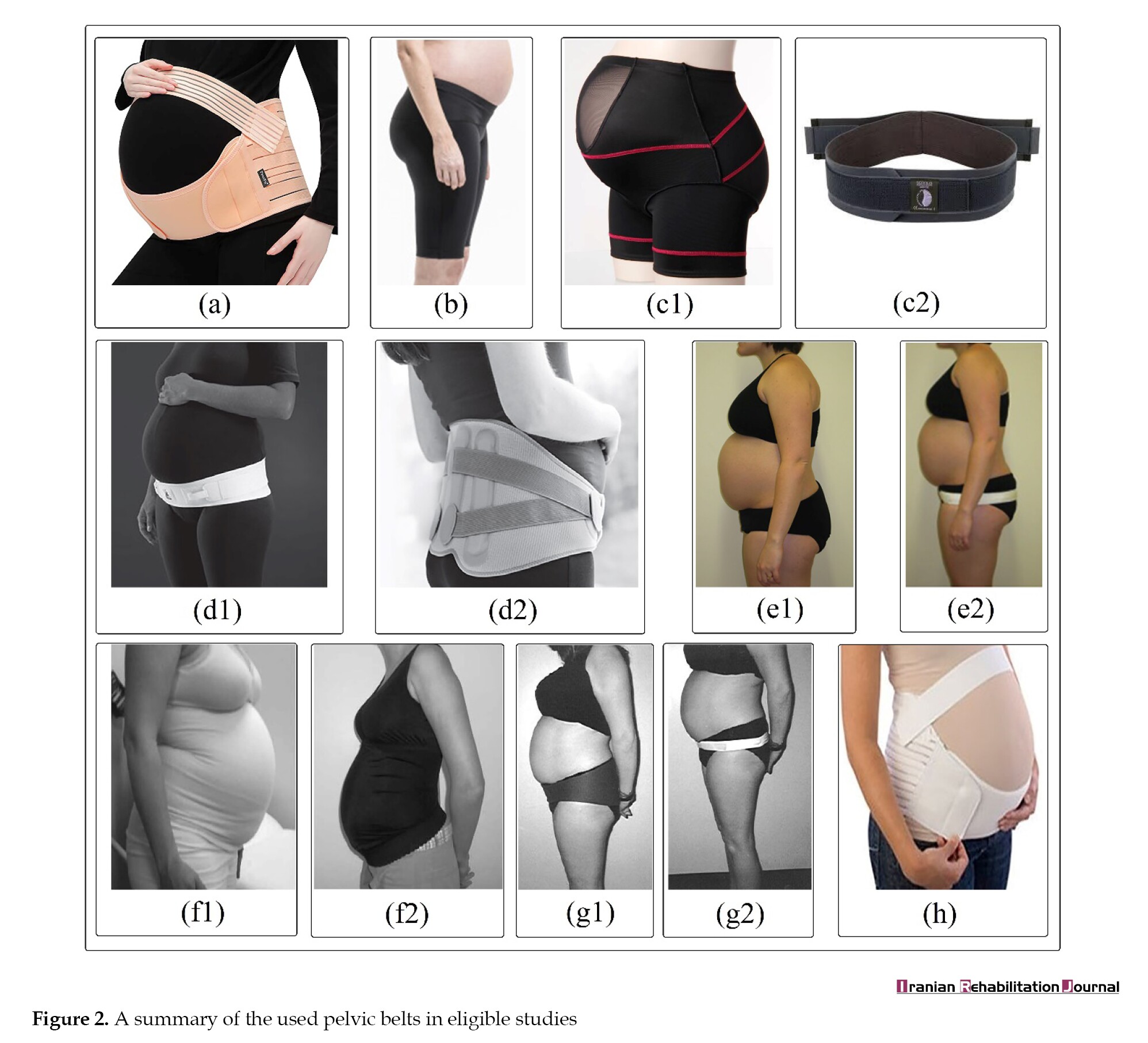

Belt types considered in studies

The included studies considered different types of belts and supports, but this review focused on the efficacy of flexible types. Bertuit et al. used the narrow flexible belt Ortel-P Thuasne and also evaluated the efficacy of a wide rigid belt [37]. Cameron et al. Szkwara et al. considered the efficacy of elastomeric dynamic elastomeric fabric orthoses and compared it with a rigid belt (SEROLA) [36, 43]. Depledge et al. and Flack et al. compared the efficacy of wide flexible and thin rigid belts [35, 38]. Marzouk et al., Kordi et al., and Carr et al. considered soft lumbopelvic belts [34, 42, 44] and Kalus et al. compared the two soft undergarments effectiveness named Tubigrip and BellyBra [29] (Figure 2).

Follow-up and adherence

The reviewed studies reported pain reduction after wearing a pelvic belt from one week [35] to 9 weeks [37] and 18 weeks [43]. One study evaluated belt efficacy for two weeks [44]. Two studies considered a three-week treatment duration [29, 38], and three studies followed patients for six weeks [34, 36, 42]. Due to the heterogeneity of the instruments used in pain intensity and function measurement, finding a correlation between the duration of belt use and pain reduction or functional improvement was impossible. Adherence to belt-wearing was varied in the included studies; the least time duration of belt-wearing was 2.5 hours a day, four days a week [37]. A total of 5 to 6 h/day was reported in two studies [35, 38], 10 h was reported by one study [36], and three studies reported daily use [34, 42, 44]. Two studies did not report the hours of belt daily usage [29, 43].

Discussion

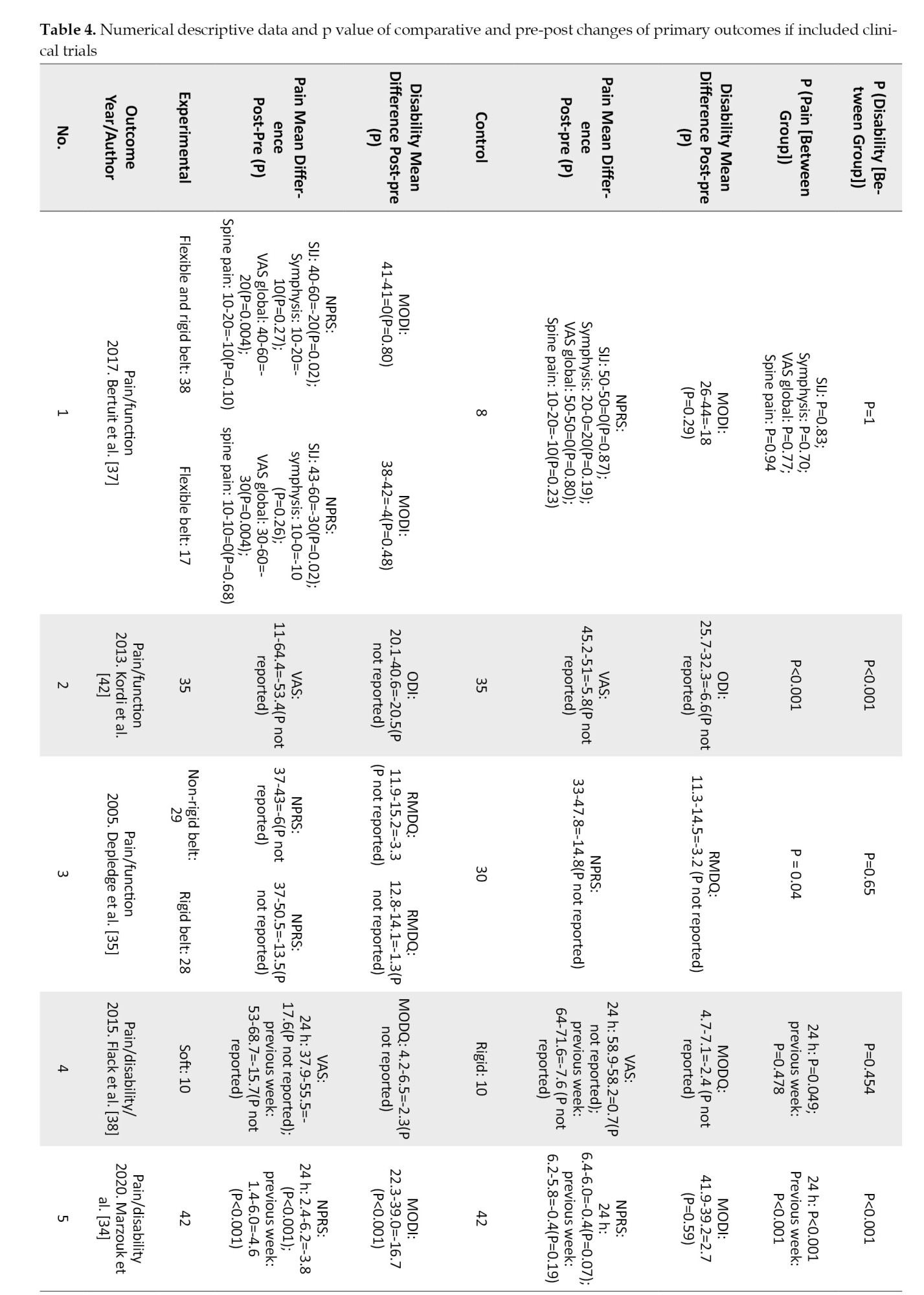

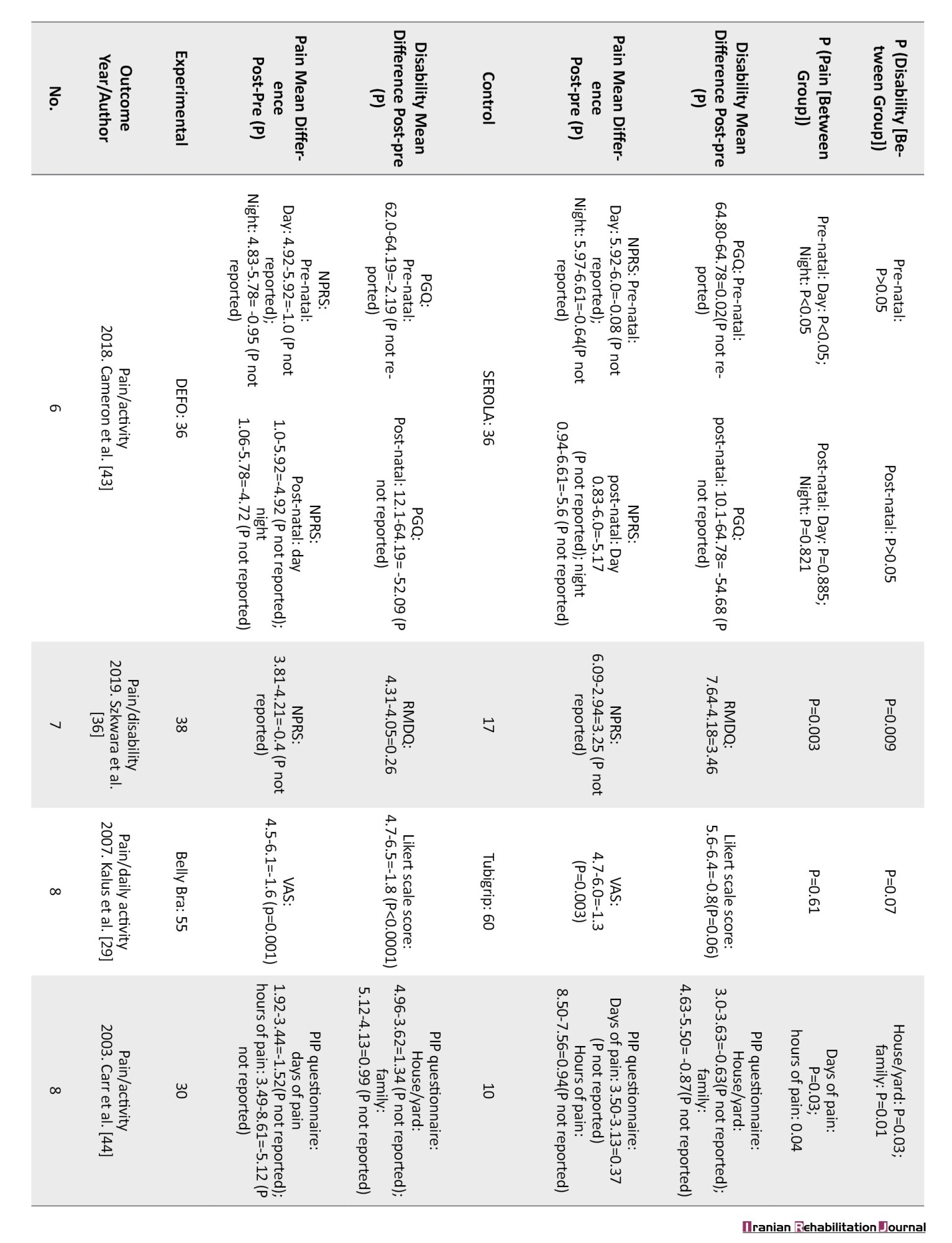

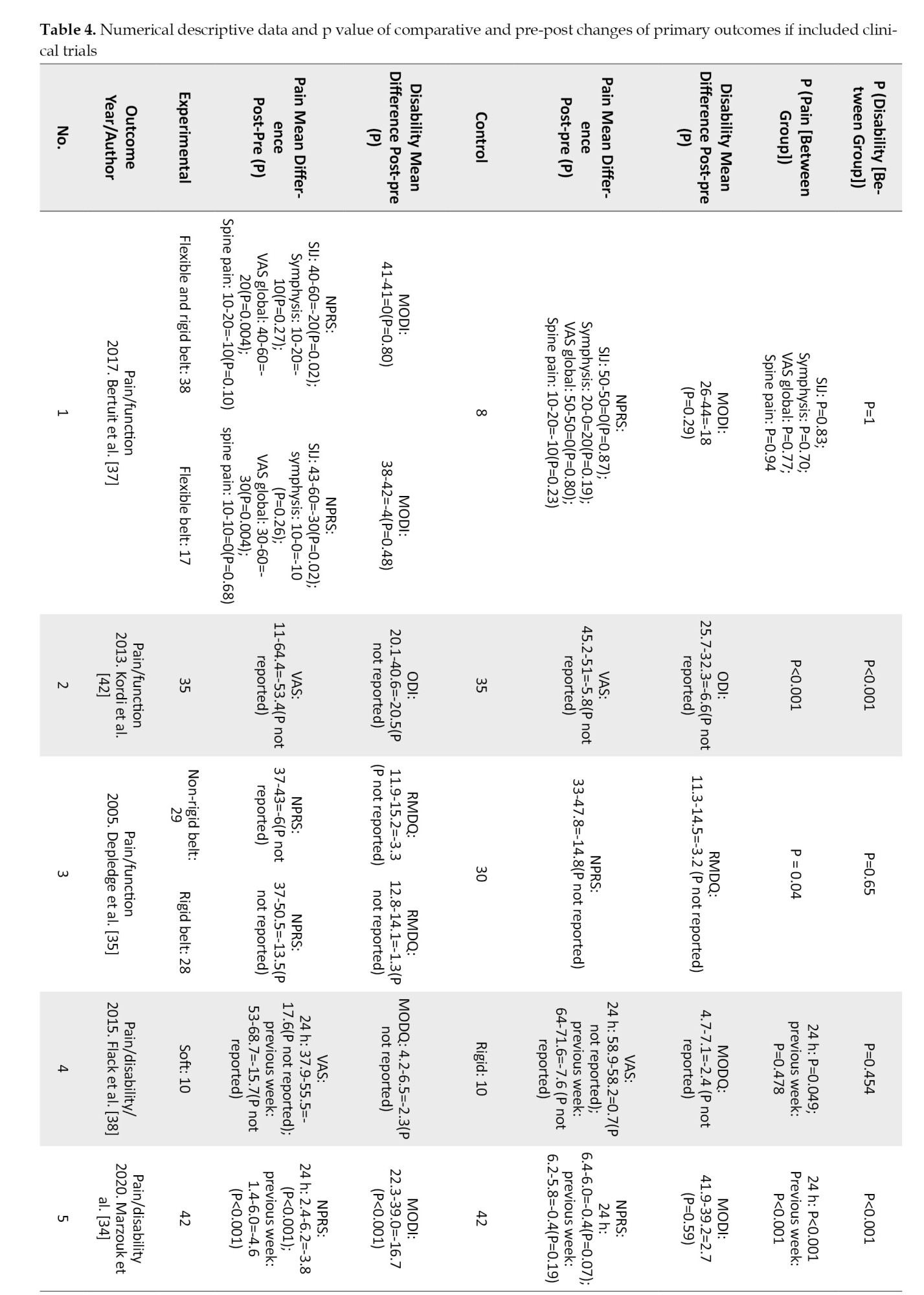

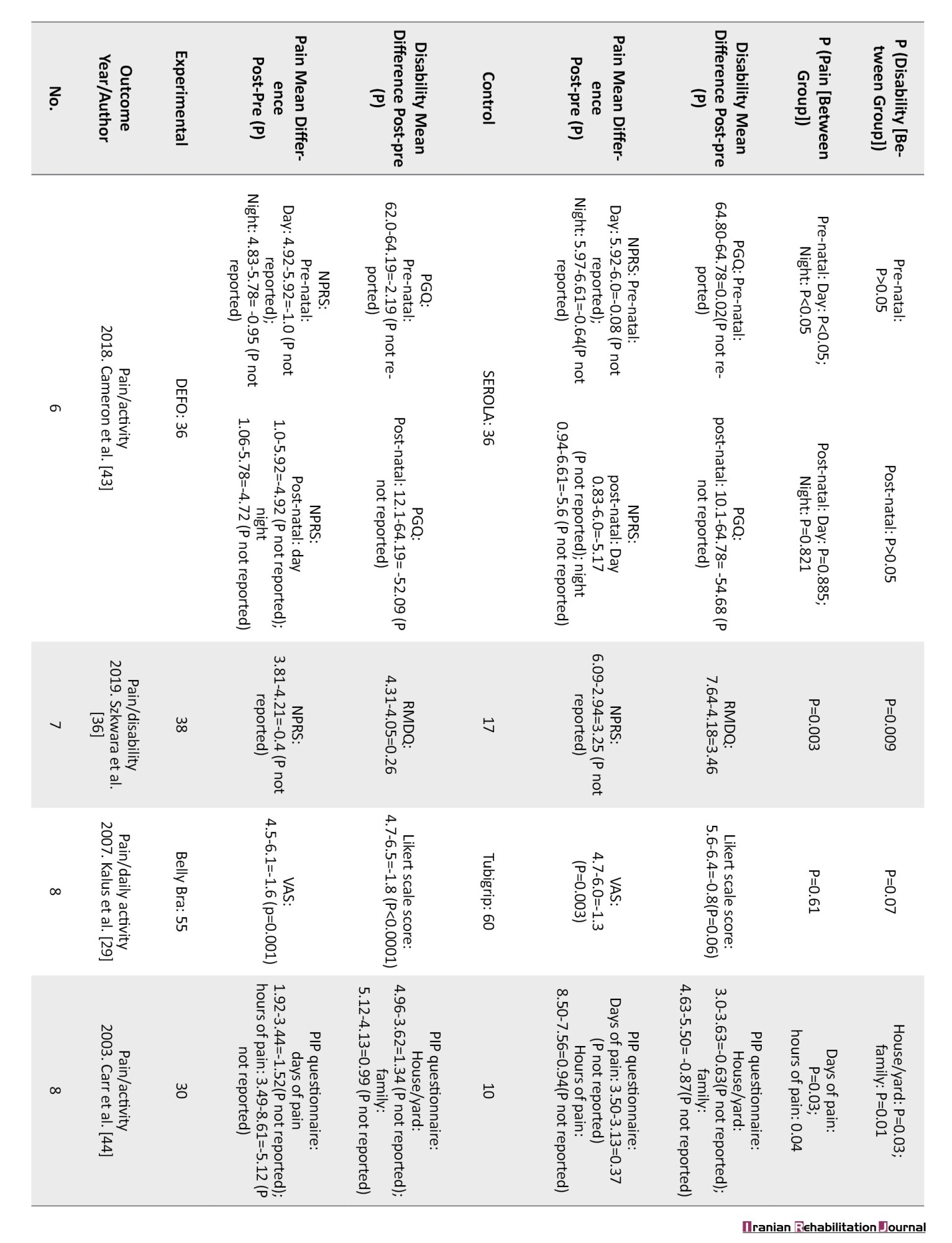

Comparing the effect of the flexible belt to healthcare or exercise on pain intensity

Pain intensity was measured using VAS in four studies and NPRS in five studies (Table 3). Nine clinical trials were considered: One low-quality, four fair-quality, and four high-quality clinical trials considered pain intensity. Eight studies (except one high-quality study) reported pain reduction after wearing the flexible pelvic garment [29, 34, 36-38, 42-44]. In five clinical trials (four fair- and one low-quality) the flexible pelvic belt was more effective in reducing pain than the control group, which received healthcare or physical therapy [34, 36, 37, 42, 44]. One high-quality randomized controlled trial [35] determined no added effect of the flexible belt on exercise and information after a one-week follow-up (Table 4). According to the clinical trials with differing levels of evidence, this review suggests using the flexible belt as a practical treatment approach to alleviating pain in pregnant women with PGP or LBP.

Comparing the effect of the flexible belt to healthcare or exercise on functional disability

Functional disability was evaluated using the Oswestry disability index or modified Oswestry disability index, Roland-Morris disability questionnaire, pelvic girdle questionnaire, Quebec back pain disability scale, and the Likert scale. The eligible studies indicated that the use of flexible belts improved function, with one low-, two fair-, and four high-quality studies reporting improvements in disability after using a flexible belt [29, 34-36, 38, 42, 43]. Among these studies, two fair-and one low-quality study reported higher efficacy of belts than healthcare or physical therapy [34, 36, 42]. While one fair-quality study found no functional improvement with or without the belt [37]. In contrast, one high-quality study that followed up after one week showed no added effect of the flexible belt on functional ability compared to health care or exercise after a one-week follow-up [35] (Table 4). Despite the favoring results of studies, the present review supposes that the literature lacks enough evidence to conclude about the added efficacy of pelvic belts to general healthcare or physical therapy in improving functional disability.

Comparing the flexible and rigid belt

Four stu Cameron dies including one fair- and three high-quality, assessed the efficacy of flexible and rigid belts [35, 37, 38, 43]. Cameron et al. found a higher efficacy of flexible dynamic elastomeric fabric orthoses during the pre-natal period than rigid SEROLA, with clinically significant efficacy. However, within the post-natal period, despite no significant difference between groups, the rigid belt helped in meaningful pain reduction [43]. Flack et al. reported a positive effect of both rigid and flexible belts on pain intensity and functional scale after three weeks of use. Pain intensity was reduced more with the flexible belt than with the rigid belt, however, there was no difference in functional status and disability between the two belt types [38]. Bertuit et al. also compared the efficacy of narrow flexible and wide rigid belts and found that both types of belts were effective in reducing pain. The flexible belt significantly decreases global and SIJ pain intensity, while rigid belts alleviate spine pain by encompassing the spine with a wide belt.

Additionally, one study found neither efficacy nor difference between flexible and rigid belts in the functional score [37]. Depledge et al. also compared the efficacy of wide flexible and narrow rigid belts and found that the rigid belt significantly reduced average pain after a one-week follow-up, but the flexible had no effect. The researchers observed no difference between the two groups in terms of the worst experienced pain or functional improvement [35] as demonstrated in Table 4.

The limited evidence available does not allow for conclusive comparisons between the efficacy of rigid and flexible belts. Furthermore, the included studies used belts of varying width and flexibility ranges, which makes it challenging to draw definitive conclusions. The studies that did show similar outcomes, but the efficacy in pain relief was controversial.

Different types of flexible belts efficacy

One high- and one low-quality study investigated the efficacy of elastomeric dynamic elastomeric fabric orthoses and reported satisfying results in pain reduction and function improvement after 18 and 6 weeks of use, respectively [36, 43]. Two high-quality studies have investigated the efficacy of a wide flexible belt [35, 38]. Flack et al. confirmed the efficacy of wide flexible belts on pain alleviation and functional improvement after three weeks of belt-wearing [38]. However, Depledge et al. did not confirm pain improvement after using a wide flexible belt for one week [35]. Three fair-quality studies have investigated the efficacy of lumbopelvic belts and confirmed their effectiveness in pain reduction and disability improvement [34, 42, 44]. One fair-quality study investigated the efficacy of a flexible narrow belt, which was effective in pain reduction but not disability [37]. One high-quality study compared the efficacy of two flexible garments (BellyBra and Tubigrip) and found that both types alleviated pain intensity. However, the BellyBra was more effective compared to the Tubigrip in functional improvement [29] (Table 4). Regarding the belt type, the sub-group analysis confirmed the efficacy of narrow flexible belts, elastomeric dynamic elastomeric fabric orthoses, and lumbopelvic belts after short or long-term wearing. However, more confirming studies are needed to establish the efficacy of wide flexible belts.

The potential mechanisms of pain and function improvement by belts

The proposed pain-alleviating mechanisms of the belt in literature can be summarized as follows. The first hypothesized mechanism is providing proprioceptive feedback. The pelvic belt’s compression force helps stimulate proprioceptive receptors in the skin layers or pelvic joints [45]. These proprioceptive receptors are responsible for providing optimal postural control [45]. The stimulated receptors improve the proprioception of the pelvic joints and help in better motor control of pelvic and lumbar muscles, reducing compensatory patterns and, thereby reducing pain and improving function [45].

The second explanation is the biomechanical effect. Pelvic garments are supposed to improve the self-locking of the pelvis and reduce SIJ laxity by increasing the “force closure,” which was discussed formerly. Enhancing force closure reduces shearing forces through the SP and SIJ and releases the strained ligaments that are the main reason for pelvic pain in pregnant women [15, 46].

The current review findings related to pain reduction due to belt wearing, extracted from randomized controlled trials and controlled trials studies, are valuable in clinical decision-making when choosing to add a belt in addition to only health instruction or physical therapy. However, the results are comparable to a systematic review from 2019 that was more specific, limiting eligible studies to higher evidence levels (II). Nevertheless, the current review finding is strong enough to judge the belt efficiency in pregnant women with pelvic or low back pain.

Conclusion

Based on the limited evidence, the current review suggests wearing a flexible belt during the 20th to 30th weeks of pregnancy. Nevertheless, the belt efficacy depends on adherence. Besides, more studies with a high level of evidence are recommended to confirm the belt efficacy with confidence.

Study limitations

This study faced some significant limitations. The pelvic belt interventions used in the included studies were different types of non-rigid pelvic belts. Additionally, the follow-up period and the adherence reported in the reviewed studies were variable, making it challenging to provide accurate conclusions in this matter. There was a lack of evidence considering the safety of pelvic belt intervention. Due to the heterogeneity of the eligible study, meta-analysis was not applicable. Moreover, the eligible high-quality randomized controlled trials were limited, which reduces the power of judgment about the efficacy of the pelvic belt. Despite these limitations, this work offers insight into the importance of the role of pain-relieving pelvic belts while managing PGP in pregnant women. Large prospective controlled studies could provide more definitive evidence.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The protocol of this review was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (Code: CRD42019121687).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology and writing the original draft: Faezeh Ghorbani, Shahrbanoo Bidari, Mohammadreza Pourahmadi; Supervision: Mohammadreza Pourahmadi; Funding administration, data collection, data analysis and investigation: All authors; Review andediting: Mohammadreza Pourahmadi, Arman Jalaleddini, Kourosh Barati.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Pelvic girdle pain (PGP) and low back pain (LBP) related to pregnancy are women’s concerns and common social challenges. According to the literature, about 30% to 78% of women suffer from an amount of PGP (deep, diffusing, irradiating, or radiating pain around the sacroiliac joint or symphysis pubis) or LBP during pregnancy or after three months post-partum [1-5]. This has been reported at a severe level in one-third of women [6]. PGP might affect sitting, walking, and standing ability leading to disability in daily activity, and is estimated as the reason for 37% of sick leaves during pregnancy [6-10]. The symptoms can be disabling, not necessarily removed after childbirth, and often later. Despite the negative effect on the quality of life, the reason for pain in pregnancy has been recognized weakly [11]. This reasonably common disorder involves hormonal fluctuations, genes and biomechanical reasons [12]. A history of LBP, pelvic injury, young age, and multiplication are raised as pregnancy-related LBP and PGP risk factors [13, 14].

According to a theoretical model of pelvic function, in the self-locking mechanism, shear force in the sacroiliac joint is prevented through augmenting friction by using two factors as follows: The particular anatomical alignment, which increases friction coefficient (form-closure), and the tension of muscles and ligaments, which cross sacroiliac joint (SIJ) and provide higher stiffness (force-closure) [15, 16]. It has been recommended that during pregnancy, hormonal (rise of fertility hormones or hormones related to parturition), mechanical factors (lengthening of pelvic joints ligaments and fascia) and changes in motor control, cause pelvic instability and consequently lead to PGP [8, 17-20]. For this reason, most treatments for PGP are based on intervention approaches that improve muscle functions and pelvic stiffness [21]. Literature has proven that multimodal interventions, including physiotherapy, pelvic belt, and supplementary interventions (ergonomic education, massage therapy, acupuncture, and yoga), are effective in LBP and PGP relief [3, 22-30]. A Cochrane review indicated the superiority of using a belt or acupuncture, physical therapy, and exercise over only taking care. However, the best treatment options are not consensually declared [25].

Pelvic belts are used to treat pelvic pain during pregnancy and postpartum. The logic for using belts is stabilizing and compressing SIJ surfaces and providing pelvic girdle stability through increasing force-closure (applying external force) [31, 32]. By this mechanism, pelvic belts might provide enough support for symphysis pubis and SIJ pain-relieving and are proposed as a primary treatment [33, 34]. Existing studies regarding the effects of wearing soft belts on pain relief have some limitations that make it difficult to decide whether to use soft belts for clinical applications. First of all, the exact effects of wearing a pelvic belt on pain reduction are controversial. Ostgaard et al. indicated that 83% of PGP or LBP women reported posterior pelvic pain reduction while wearing a pelvic belt [33]. However, other studies did not report any pain-relieving after pelvic belt use [35]. Secondly, the pure effect of pelvic belts is difficult to specify, as they are used in combination with other treatments such as exercise and acupuncture. Thirdly, different belts are used [29, 31, 35, 36] and the best type regarding symptom relief and patient tolerance has not been specified yet.

Furthermore, a pelvic belt is used in clinical applications and other treatments, such as exercise and acupuncture. Therefore, their pure effect is not specified. Moreover, different belts are used [29, 31, 35, 36] and the best type regarding symptom relief and patient tolerance has not been specified yet. Some researchers investigated the effect of different positions (high position in anterior superior iliac spine level and low position in greater trochanter level and pubis joint) [31, 37] and flexibility (rigid and flexible) of the belt [37, 38] and different amounts of compressive force (50 and 100 N) [39] using biomechanical models. Two systematic reviews in 2019 indicated the positive effect of using dynamic elastomeric fabric orthosis or maternity support garments on pain and function during the pre-natal period [40, 41]. However, adherence to the principle of comprehensiveness (encompassing gray literature) and adherence to the principle of quality is missed in older systematic reviews. Moreover, the previous reviews considered different evidence levels. Therefore, to the best of our knowledge, a lack of consistent and citable evidence is considered regarding the exact effect of pelvic belts on pregnancy-related PGP and LBP. Accordingly, the current study reviews level II literature (randomized control trials or control trials) considering pelvic belt efficacy on pain, improves function in pregnant women with PGP and LBP, and provides a practical and clinical recommendation regarding the ability of pelvic belt prescription in pregnant women, and suggests when to use a pelvic belt during pregnancy.

Materials and Methods

This study was developed based on the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses principles.

Search strategy

Two reviewers independently performed a computerized literature search from PubMed/MEDLINE (NLM), Scopus, Web of Science, PEDro and Google Scholar. The key terms used in PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science and Scopus included the following items: ([Pelvic AND pain*] OR [pelvic girdle AND pain*] OR [pelvic AND girdle pain*] OR [symphysis pubis AND dysfunction*] OR [pubis dysfunction* AND symphysis]) AND ([pregnant* AND woman*] OR [pregnant*] OR [gestation*]) AND ([brace*] OR [belt*] OR [semirigid AND belt*] OR [nonrigid AND belt*] OR [maternity AND garment*] OR [pelvic AND belt*) OR [soft AND belt*]OR [support AND garment*] OR [pelvic support AND belts*] NOT [seat AND belt*]).

Study selection

Eligibility criteria

Table 1 provides details on study eligibility criteria using the population, intervention, comparison, outcome, and study design framework.

Selection procedure

The review included studies in which pregnant women with PGP used a pelvic belt or pelvic supports to relieve pain. Experimental studies, including randomized controlled trials, non-randomized controlled trials (allocation performed with the date of birth, alteration or record numbers) or randomized comparative trials, were considered for this review. The review only included the studies published within 21 years (April 2000 to April 2021), published in peer-reviewed journals, full-text articles, and written in English. Two independent researchers (SB/FG) evaluated the identified studies for eligibility by screening the title and abstract, and then the full texts, grading each study as eligible/not eligible/might be eligible at each stage. Included studies were agreed upon by the two reviewers (SB/FG) and in case of disagreement, a third reviewer (MPA) mediated. The details, including sample size, intervention type, duration, and outcome measures, were extracted from the articles. The full texts of selected studies were obtained, and then two reviewers appraised the studies independently and scored them based on 11 points on the PeDro scale. A third collaborator resolved any disagreements in selecting the studies and scoring them. The complete process of study selection is summarized in the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses principles flow diagram (Figure 1).

Data extraction

The researchers extracted the data, which was then rechecked by a third reviewer. As data were missing or ambiguous, trial authors were contacted for additional data.

The following information was extracted: Trial authors, countries, study design, the week of pregnancy, sample size, interventions, type of belt, study setting, outcome measures, follow-up period, and main results. Data related to crucial outcome measures, including pain and disability, were extracted.

Quality assessment in individual trials

The two reviewers (SB/FG) underwent training and conducted a pilot quality assessment. They evaluated the quality of each included trial independently, using the PeDro quality assessment tool informed by empirical evidence to assess internal validity. The third reviewer (MPA) commented on the following discussion for any disagreement. Each quality component was reported as low, fair, or high quality in tabular form.

Results

A total of 1188 studies were identified during the search across different databases. Additionally, a hand search of references provided in studies yielded one more study. After removing duplicates of different databases and records marked as ineligible by automation tools, 544 articles remained. Upon initial review, the titles and abstracts of the articles were reviewed and 64 articles were selected for more surveys. In the next step, the full text of the articles was carefully reviewed, and 55 articles were excluded based on predetermined criteria. Nine articles met the inclusion criteria and were selected for the systematic review (Figure 1).

Quality of included studies

The quality was considered for all studies. One study was rated as low quality, four were rated as fair quality, and four were rated as high quality. Table 2 shows the quality of the included studies.

Review of participant characteristics

Table 3 shows eligible trial population characteristics. According to the included studies, PGP is described as pain in the symphysis pubis or SIJ in pregnant women [34-38, 42, 43]. Two studies from New Zealand considered symphysis pubis [35, 38]. One study from Belgium [37] and one from the United Kingdom [43] considered SIJ or symphysis pubis. One study from Iran considered SIJ [42]. One study from Egypt and one from Australia considered lumbar spine or posterior pelvic pain [34, 36], one from the USA considered LBP [44] and one study from Australia considered two types of bra [29]. All of the studies considered pregnant women and the mean age ranged between 26.72 and 30. Two studies did not report the mean age of the included participants [29, 36]. The study by Flack et al. justified the compared groups for patient-specific functional scale pre-intervention [38]. At the start of the intervention, the gestational age was between the 23rd and 32nd weeks of maternity. Szkwara et al. started the intervention at the earliest time (23th-25th week) [36] and Depledge et al. and Flack et al. started the intervention at a mean age of 31st gestational week [35, 38].

Methodology considered and outcome measures

Nine papers that met the inclusion criteria were evaluated. Two studies were performed in a quasi-experimental design (controlled trials) [34, 36] and three studies were randomized comparative trials that compared the efficacy of two types of maternity support [29, 38, 43]. Four studies were performed in randomized control trials design [35, 37, 42, 44]. In four studies [35, 37, 38, 43], both types of non-rigid and rigid pelvic support were evaluated, and five studies evaluated the therapeutic effect of the non-rigid belt as an intervention [29, 34, 36, 42, 44]. As a result, the team decided to consider the results of the non-rigid pelvic support for systematic review.

The pain was measured using the visual analog scale [29, 37, 38, 42] or the numeric pain rating scale [34-36, 43], or the pain in pregnancy questionnaire [44]. Disability was measured using the Oswestry disability index [42], a modified version of the oswestry disability index [34, 38], the patient-specific functional scale [35, 38], the Quebec back pain disability scale [37], the Roland Morris disability questionnaire [35, 36], the pelvic girdle questionnaire [43] or a Likert scale [29, 44]. Pain and disability were evaluated as the primary outcome measures.

Belt types considered in studies

The included studies considered different types of belts and supports, but this review focused on the efficacy of flexible types. Bertuit et al. used the narrow flexible belt Ortel-P Thuasne and also evaluated the efficacy of a wide rigid belt [37]. Cameron et al. Szkwara et al. considered the efficacy of elastomeric dynamic elastomeric fabric orthoses and compared it with a rigid belt (SEROLA) [36, 43]. Depledge et al. and Flack et al. compared the efficacy of wide flexible and thin rigid belts [35, 38]. Marzouk et al., Kordi et al., and Carr et al. considered soft lumbopelvic belts [34, 42, 44] and Kalus et al. compared the two soft undergarments effectiveness named Tubigrip and BellyBra [29] (Figure 2).

Follow-up and adherence

The reviewed studies reported pain reduction after wearing a pelvic belt from one week [35] to 9 weeks [37] and 18 weeks [43]. One study evaluated belt efficacy for two weeks [44]. Two studies considered a three-week treatment duration [29, 38], and three studies followed patients for six weeks [34, 36, 42]. Due to the heterogeneity of the instruments used in pain intensity and function measurement, finding a correlation between the duration of belt use and pain reduction or functional improvement was impossible. Adherence to belt-wearing was varied in the included studies; the least time duration of belt-wearing was 2.5 hours a day, four days a week [37]. A total of 5 to 6 h/day was reported in two studies [35, 38], 10 h was reported by one study [36], and three studies reported daily use [34, 42, 44]. Two studies did not report the hours of belt daily usage [29, 43].

Discussion

Comparing the effect of the flexible belt to healthcare or exercise on pain intensity

Pain intensity was measured using VAS in four studies and NPRS in five studies (Table 3). Nine clinical trials were considered: One low-quality, four fair-quality, and four high-quality clinical trials considered pain intensity. Eight studies (except one high-quality study) reported pain reduction after wearing the flexible pelvic garment [29, 34, 36-38, 42-44]. In five clinical trials (four fair- and one low-quality) the flexible pelvic belt was more effective in reducing pain than the control group, which received healthcare or physical therapy [34, 36, 37, 42, 44]. One high-quality randomized controlled trial [35] determined no added effect of the flexible belt on exercise and information after a one-week follow-up (Table 4). According to the clinical trials with differing levels of evidence, this review suggests using the flexible belt as a practical treatment approach to alleviating pain in pregnant women with PGP or LBP.

Comparing the effect of the flexible belt to healthcare or exercise on functional disability

Functional disability was evaluated using the Oswestry disability index or modified Oswestry disability index, Roland-Morris disability questionnaire, pelvic girdle questionnaire, Quebec back pain disability scale, and the Likert scale. The eligible studies indicated that the use of flexible belts improved function, with one low-, two fair-, and four high-quality studies reporting improvements in disability after using a flexible belt [29, 34-36, 38, 42, 43]. Among these studies, two fair-and one low-quality study reported higher efficacy of belts than healthcare or physical therapy [34, 36, 42]. While one fair-quality study found no functional improvement with or without the belt [37]. In contrast, one high-quality study that followed up after one week showed no added effect of the flexible belt on functional ability compared to health care or exercise after a one-week follow-up [35] (Table 4). Despite the favoring results of studies, the present review supposes that the literature lacks enough evidence to conclude about the added efficacy of pelvic belts to general healthcare or physical therapy in improving functional disability.

Comparing the flexible and rigid belt

Four stu Cameron dies including one fair- and three high-quality, assessed the efficacy of flexible and rigid belts [35, 37, 38, 43]. Cameron et al. found a higher efficacy of flexible dynamic elastomeric fabric orthoses during the pre-natal period than rigid SEROLA, with clinically significant efficacy. However, within the post-natal period, despite no significant difference between groups, the rigid belt helped in meaningful pain reduction [43]. Flack et al. reported a positive effect of both rigid and flexible belts on pain intensity and functional scale after three weeks of use. Pain intensity was reduced more with the flexible belt than with the rigid belt, however, there was no difference in functional status and disability between the two belt types [38]. Bertuit et al. also compared the efficacy of narrow flexible and wide rigid belts and found that both types of belts were effective in reducing pain. The flexible belt significantly decreases global and SIJ pain intensity, while rigid belts alleviate spine pain by encompassing the spine with a wide belt.

Additionally, one study found neither efficacy nor difference between flexible and rigid belts in the functional score [37]. Depledge et al. also compared the efficacy of wide flexible and narrow rigid belts and found that the rigid belt significantly reduced average pain after a one-week follow-up, but the flexible had no effect. The researchers observed no difference between the two groups in terms of the worst experienced pain or functional improvement [35] as demonstrated in Table 4.

The limited evidence available does not allow for conclusive comparisons between the efficacy of rigid and flexible belts. Furthermore, the included studies used belts of varying width and flexibility ranges, which makes it challenging to draw definitive conclusions. The studies that did show similar outcomes, but the efficacy in pain relief was controversial.

Different types of flexible belts efficacy

One high- and one low-quality study investigated the efficacy of elastomeric dynamic elastomeric fabric orthoses and reported satisfying results in pain reduction and function improvement after 18 and 6 weeks of use, respectively [36, 43]. Two high-quality studies have investigated the efficacy of a wide flexible belt [35, 38]. Flack et al. confirmed the efficacy of wide flexible belts on pain alleviation and functional improvement after three weeks of belt-wearing [38]. However, Depledge et al. did not confirm pain improvement after using a wide flexible belt for one week [35]. Three fair-quality studies have investigated the efficacy of lumbopelvic belts and confirmed their effectiveness in pain reduction and disability improvement [34, 42, 44]. One fair-quality study investigated the efficacy of a flexible narrow belt, which was effective in pain reduction but not disability [37]. One high-quality study compared the efficacy of two flexible garments (BellyBra and Tubigrip) and found that both types alleviated pain intensity. However, the BellyBra was more effective compared to the Tubigrip in functional improvement [29] (Table 4). Regarding the belt type, the sub-group analysis confirmed the efficacy of narrow flexible belts, elastomeric dynamic elastomeric fabric orthoses, and lumbopelvic belts after short or long-term wearing. However, more confirming studies are needed to establish the efficacy of wide flexible belts.

The potential mechanisms of pain and function improvement by belts

The proposed pain-alleviating mechanisms of the belt in literature can be summarized as follows. The first hypothesized mechanism is providing proprioceptive feedback. The pelvic belt’s compression force helps stimulate proprioceptive receptors in the skin layers or pelvic joints [45]. These proprioceptive receptors are responsible for providing optimal postural control [45]. The stimulated receptors improve the proprioception of the pelvic joints and help in better motor control of pelvic and lumbar muscles, reducing compensatory patterns and, thereby reducing pain and improving function [45].

The second explanation is the biomechanical effect. Pelvic garments are supposed to improve the self-locking of the pelvis and reduce SIJ laxity by increasing the “force closure,” which was discussed formerly. Enhancing force closure reduces shearing forces through the SP and SIJ and releases the strained ligaments that are the main reason for pelvic pain in pregnant women [15, 46].

The current review findings related to pain reduction due to belt wearing, extracted from randomized controlled trials and controlled trials studies, are valuable in clinical decision-making when choosing to add a belt in addition to only health instruction or physical therapy. However, the results are comparable to a systematic review from 2019 that was more specific, limiting eligible studies to higher evidence levels (II). Nevertheless, the current review finding is strong enough to judge the belt efficiency in pregnant women with pelvic or low back pain.

Conclusion

Based on the limited evidence, the current review suggests wearing a flexible belt during the 20th to 30th weeks of pregnancy. Nevertheless, the belt efficacy depends on adherence. Besides, more studies with a high level of evidence are recommended to confirm the belt efficacy with confidence.

Study limitations

This study faced some significant limitations. The pelvic belt interventions used in the included studies were different types of non-rigid pelvic belts. Additionally, the follow-up period and the adherence reported in the reviewed studies were variable, making it challenging to provide accurate conclusions in this matter. There was a lack of evidence considering the safety of pelvic belt intervention. Due to the heterogeneity of the eligible study, meta-analysis was not applicable. Moreover, the eligible high-quality randomized controlled trials were limited, which reduces the power of judgment about the efficacy of the pelvic belt. Despite these limitations, this work offers insight into the importance of the role of pain-relieving pelvic belts while managing PGP in pregnant women. Large prospective controlled studies could provide more definitive evidence.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The protocol of this review was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (Code: CRD42019121687).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology and writing the original draft: Faezeh Ghorbani, Shahrbanoo Bidari, Mohammadreza Pourahmadi; Supervision: Mohammadreza Pourahmadi; Funding administration, data collection, data analysis and investigation: All authors; Review andediting: Mohammadreza Pourahmadi, Arman Jalaleddini, Kourosh Barati.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Abebe E, Singh K, Adefires M, Abraha M, Gebremichael H, Krishnan R. History of low back pain during previous pregnancy had an effect on development of low back pain in current pregnancy attending antenatal care clinic of the University of Gondar Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Journal of Medical Science and Technology. 2014; 3(3):37-44. [Link]

- Colla C, Paiva LL, Thomaz RP. Therapeutic exercise for pregnancy low back and pelvic pain: A systematic review. Fisioterapia em Movimento. 2017; 30(2):399-411. [DOI: 10.1590/1980-5918.030.002.AR03]

- Ho SS, Yu WW, Lao TT, Chow DH, Chung JW, Li Y. Effectiveness of maternity support belts in reducing low back pain during pregnancy: A review. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2009; 18(11):1523-32. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02749.x] [PMID]

- Hughes CM, Liddle SD, Sinclair M, McCullough JEM. The use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for pregnancy related low back and/or pelvic girdle pain: An online survey. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 2018; 31:379-83. [DOI:10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.01.015] [PMID]

- Wang SM, DeZinno P, Fermo L, William K, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Bravemen F, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine for low-back pain in pregnancy: A cross-sectional survey. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine. 2005; 11(3):459-64. [DOI:10.1089/acm.2005.11.459] [PMID]

- Liddle SD, Pennick V. Interventions for preventing and treating low-back and pelvic pain during pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015; 2015(9):CD001139.[DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD001139.pub4] [PMID]

- Backhausen M, Damm P, Bendix J, Tabor A, Hegaard H. The prevalence of sick leave: Reasons and associated predictors-A survey among employed pregnant women. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare. 2018; 15:54-61. [DOI:10.1016/j.srhc.2017.11.005] [PMID]

- Aldabe D, Milosavljevic S, Bussey MD. Is pregnancy related pelvic girdle pain associated with altered kinematic, kinetic and motor control of the pelvis? A systematic review. European Spine Journal. 2012; 21(9):1777-87. [DOI:10.1007/s00586-012-2401-1] [PMID]

- Stuge B, Holm I, Vøllestad N. To treat or not to treat postpartum pelvic girdle pain with stabilizing exercises? Manual Therapy. 2006; 11(4):337-43. [DOI:10.1016/j.math.2005.07.004] [PMID]

- Hansen A, Jensen DV, Wormslev M, Minck H, Johansen S, Larsen EC, et al. Symptom-giving pelvic girdle relaxation in pregnancy. II: Symptoms and clinical signs. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1999; 78(2):111-5. [PMID]

- Vleeming A, Albert HB, Ostgaard HC, Sturesson B, Stuge B. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. European Spine Journal. 2008; 17(6):794-819. doi: [DOI:10.1007/s00586-008-0602-4] [PMID]

- Kanakaris NK, Roberts CS, Giannoudis PV. Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain: An update. BMC Medicine. 2011; 9:15. [DOI:10.1186/1741-7015-9-15] [PMID]

- Fitzgerald CM, Segal N. Musculoskeletal health in pregnancy and postpartum. Berlin: Springer; 2015. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-14319-4]

- Katonis P, Kampouroglou A, Aggelopoulos A, Kakavelakis K, Lykoudis S, Makrigiannakis A, et al. Pregnancy-related low back pain. Hippokratia. 2011; 15(3):205-10. [PMID]

- Snijders CJ, Vleeming A, Stoeckart R. Transfer of lumbosacral load to iliac bones and legs Part 1: Biomechanics of self-bracing of the sacroiliac joints and its significance for treatment and exercise. Clinical Biomechanics. 1993; 8(6):285-94. [DOI:10.1016/0268-0033(93)90002-Y] [PMID]

- van Wingerden JP, Vleeming A, Buyruk HM, Raissadat K. Stabilization of the sacroiliac joint in vivo: Verification of muscular contribution to force closure of the pelvis. European Spine Journal. 2004; 13(3):199-205. [DOI:10.1007/s00586-003-0575-2] [PMID]

- Damen L, Buyruk HM, Güler-Uysal F, Lotgering FK, Snijders CJ, Stam HJ. The prognostic value of asymmetric laxity of the sacroiliac joints in pregnancy-related pelvic pain. Spine. 2002; 27(24):2820-4. [DOI:10.1097/00007632-200212150-00018] [PMID]

- Kristiansson P, Svärdsudd K, von Schoultz B. Reproductive hormones and aminoterminal propeptide of type III procollagen in serum as early markers of pelvic pain during late pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999; 180(1):128-34. [DOI:10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70162-6] [PMID]

- Mens JM, Vleeming A, Stoeckart R, Stam HJ, Snijders CJ. Understanding peripartum pelvic pain: Implications of a patient survey. Spine. 1996; 21(11):1363-9. [PMID]

- Mens JM, Pool-Goudzwaard A, Stam HJ. Mobility of the pelvic joints in pregnancy-related lumbopelvic pain: A systematic review. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 2009; 64(3):200-8. [DOI:10.1097/OGX.0b013e3181950f1b] [PMID]

- Fitzgerald CM, Mallinson T. The association between pelvic girdle pain and pelvic floor muscle function in pregnancy. International Urogynecology Journal. 2012; 23(7):893-98. [DOI:10.1007/s00192-011-1658-y] [PMID]

- Waterfield J, Bartlam B, Bishop A, Holden MA, Barlas P, Foster NE. Physical therapists’ views and experiences of pregnancy-related low back pain and the role of acupuncture: Qualitative exploration. Physical Therapy. 2015; 95(9):1234-43. [DOI:10.2522/ptj.20140298] [PMID]

- Hammer N, Möbius R, Schleifenbaum S, Hammer KH, Klima S, Lange JS, et al. Pelvic belt effects on health outcomes and functional parameters of patients with sacroiliac joint pain. PloS One. 2015; 10(10):e0140090. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0140090] [PMID]

- George JW, Skaggs CD, Thompson PA, Nelson DM, Gavard JA, Gross GA. A randomized control trial comparing a multimodal intervention and standard obstetrics care for low back and pelvic pain in surgery. Obstetric Anesthesia Digest. 2014; 34(1):45-6. [DOI:10.1097/01.aoa.0000443391.37916.f3]

- Pennick V, Liddle SD. Interventions for preventing and treating pelvic and back pain in pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013. [DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD001139.pub3]

- Walters C, West S, Nippita T. Pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy. Australian Journal of General Practice. 2018; 47(7):439-43.[DOI:10.31128/AJGP-01-18-4467] [PMID]

- Reyhan AÇ, Dereli EE, Çolak TK. Low back pain during pregnancy and Kinesio tape application. Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. 2017; 30(3):609-13. [DOI:10.3233/BMR-160584] [PMID]

- Sklempe Kokic I, Ivanisevic M, Uremovic M, Kokic T, Pisot R, Simunic B. Effect of therapeutic exercises on pregnancy-related low back pain and pelvic girdle pain: Secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2017; 49(3):251-7. [DOI:10.2340/16501977-2196] [PMID]

- Kalus SM, Kornman LH, Quinlivan JA. Managing back pain in pregnancy using a support garment: A randomised trial. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2008; 115(1):68-75. [DOI:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01538.x] [PMID]

- Haakstad LA, Bø K. Effect of a regular exercise programme on pelvic girdle and low back pain in previously inactive pregnant women: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2015; 47(3):229-34. [DOI:10.2340/16501977-1906] [PMID]

- Mens JM, Damen L, Snijders CJ, Stam HJ. The mechanical effect of a pelvic belt in patients with pregnancy-related pelvic pain. Clinical Biomechanics. 2006; 21(2):122-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.08.016] [PMID]

- Pool-Goudzwaard A, Vleeming A, Stoeckart R, Snijders C, Mens JM. Insufficient lumbopelvic stability: A clinical, anatomical and biomechanical approach to ‘a-specific’low back pain. Manual Therapy. 1998; 3(1):12-20. [DOI:10.1054/math.1998.0311] [PMID]

- Ostgaard HC, Zetherström G, Roos-Hansson E, Svanberg B. Reduction of back and posterior pelvic pain in pregnancy. Spine. 1994; 19(8):894-900. [DOI:10.1097/00007632-199404150-00005] [PMID]

- Marzouk T, Fadel EA. Effect of a lumbopelvic belt versus pelvic strengthening exercise on the level of pregnancy-related low back pain. Journal of Nursing and Health Science. 2020; 9(1):1-12. [Link]

- Depledge J, McNair PJ, Keal-Smith C, Williams M. Management of symphysis pubis dysfunction during pregnancy using exercise and pelvic support belts. Physical Therapy. 2005; 85(12):1290-300. [DOI:10.1093/ptj/85.12.1290] [PMID]

- Szkwara JM, Hing W, Pope R, Rathbone E. Compression shorts reduce prenatal pelvic and low back pain: A prospective quasi-experimental controlled study. PeerJ. 2019; 7:e7080. [DOI:10.7717/peerj.7080] [PMID]

- Bertuit J, Van Lint CE, Rooze M, Feipel V. Pregnancy and pelvic girdle pain: Analysis of pelvic belt on pain. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2018; 27(1-2):e129-37. [DOI:10.1111/jocn.13888] [PMID]

- Flack NA, Hay-Smith EJ, Stringer MD, Gray AR, Woodley SJ. Adherence, tolerance and effectiveness of two different pelvic support belts as a treatment for pregnancy-related symphyseal pain - a pilot randomized trial. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2015; 15:36. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-015-0468-5] [PMID]

- Pel JJ, Spoor CW, Goossens RH, Pool-Goudzwaard AL. Biomechanical model study of pelvic belt influence on muscle and ligament forces. Journal of Biomechanics. 2008; 41(9):1878-84. [DOI:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.04.002] [PMID]

- Szkwara JM, Milne N, Hing W, Pope R. Effectiveness, feasibility, and acceptability of Dynamic Elastomeric Fabric Orthoses (DEFO) for managing pain, functional capacity, and quality of life during prenatal and postnatal care: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(13):2408. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph16132408] [PMID]

- Quintero Rodriguez C, Troynikov O. The effect of maternity support garments on alleviation of pains and discomforts during pregnancy: A systematic review. Journal of Pregnancy. 2019; 2019:2163790. [DOI:10.1155/2019/2163790] [PMID]

- Kordi R, Abolhasani M, Rostami M, Hantoushzadeh S, Mansournia MA, Vasheghani-Farahani F. Comparison between the effect of lumbopelvic belt and home based pelvic stabilizing exercise on pregnant women with pelvic girdle pain; a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. 2013; 26(2):133-9. [DOI:10.3233/BMR-2012-00357] [PMID]

- Cameron L, Marsden J, Watkins K, Freeman J. Management of antenatal pelvic girdle pain study (MAPS): A double blinded randomised trial evaluating the effectiveness of two pelvic orthoses. International Journal of Women’s Health Care. 2018; 3(2):1-9. [Link]

- Carr CA. Use of a maternity support binder for relief of pregnancy-related back pain. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 2003; 32(4):495-502. [DOI:10.1177/0884217503255196] [PMID]

- Soisson O, Lube J, Germano A, Hammer KH, Josten C, Sichting F, et al. Pelvic belt effects on pelvic morphometry, muscle activity, and body balance in patients with sacroiliac joint dysfunction. PLoS One. 2015; 10(3):e0116739. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0116739] [PMID]

- Arumugam A, Milosavljevic S, Woodley S, Sole G. Effects of external pelvic compression on form closure, force closure, and neuromotor control of the lumbopelvic spine-a systematic review. Manual Therapy. 2012; 17(4):275-84. [PMID]

Article type: Reviews |

Subject:

Orthosis and Prosthesis

Received: 2023/01/18 | Accepted: 2023/08/19 | Published: 2024/06/1

Received: 2023/01/18 | Accepted: 2023/08/19 | Published: 2024/06/1

Send email to the article author