Volume 23, Issue 3 (September 2025)

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2025, 23(3): 287-296 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Vaziri M H, Feyzi V, Sobhanian M, Vaziri F, Roostayi M M, Ahangari Z et al . Studying the Effects of Ergonomic Interventions on Cervical and Lumbar Spine Pain in Dentists. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2025; 23 (3) :287-296

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2175-en.html

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2175-en.html

Mohammad Hossein Vaziri1

, Vafa Feyzi2

, Vafa Feyzi2

, Mahdis Sobhanian2

, Mahdis Sobhanian2

, Fahimeh Vaziri1

, Fahimeh Vaziri1

, Mohammad Mohsen Roostayi3

, Mohammad Mohsen Roostayi3

, Zohreh Ahangari4

, Zohreh Ahangari4

, Ali Salehi Sahlabadi *5

, Ali Salehi Sahlabadi *5

, Vafa Feyzi2

, Vafa Feyzi2

, Mahdis Sobhanian2

, Mahdis Sobhanian2

, Fahimeh Vaziri1

, Fahimeh Vaziri1

, Mohammad Mohsen Roostayi3

, Mohammad Mohsen Roostayi3

, Zohreh Ahangari4

, Zohreh Ahangari4

, Ali Salehi Sahlabadi *5

, Ali Salehi Sahlabadi *5

1- Workplace Health Promotion Research Center, Research Institute for Health Sciences and Environment, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Occupational Health and Safety at Work, School of Public Health and Safety, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Physiotherapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Endodontics, School of Dentistry, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

5- Department of Occupational Health and Safety at Work, School of Public Health and Safety, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. & Safety Promotion and Injury Prevention Research Center, Research Institute for Health Sciences and Environment, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Occupational Health and Safety at Work, School of Public Health and Safety, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Physiotherapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Endodontics, School of Dentistry, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

5- Department of Occupational Health and Safety at Work, School of Public Health and Safety, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. & Safety Promotion and Injury Prevention Research Center, Research Institute for Health Sciences and Environment, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 670 kb]

(718 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3438 Views)

Full-Text: (453 Views)

Introduction

Ergonomics is a science that deals with the interaction between humans and their environment and is used to design work environments that increase human well-being and system performance [1]. Ergonomics encompasses all aspects of the work environment, and the physical aspects of the workplace directly influence various factors, including productivity, health, safety, comfort, job satisfaction, and overall morale [2]. The ergonomic conditions of individuals and their surroundings are of significant importance [3]. Therefore, in the case of non-conformity, musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) and discomfort occur in people, which are one of the main causes of disability worldwide and a significant increase in social costs [4].

MSDs refer to injuries and diseases affecting different parts of the body that are caused or exacerbated by manual handling, prolonged standing, and poor posture [5, 6]. Work-related MSDs in the lower limbs, especially in the lower back and knees, were more prevalent than other similar studies in Iran [7]. If it continues, it causes physical and emotional fatigue, and job burnout, which is considered a significant issue among health service providers [8]. According to the nature and working conditions, the dental profession requires an inappropriate body posture, which includes bending the head and neck forward and sideways, as well as tilting and turning the trunk towards the patient, thereby putting pressure on the musculoskeletal system [9].

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) MSD, neck pain is a crucial occupational health issue in the field of dentistry [10]. Alotaibi et al. showed that neck and back pain are the most common among dentists [11]. MSDs in the dental profession among Iranian dentists are a serious issue, and studies conducted in this field can be cited. In a study by Harris et al. conducted in Canada, 83% of dentists had MSDs [12]. Roozegar et al reported a high prevalence of such disorders [13]. Sedaghati et al also reported similar results in their study, and half of the dentists in the studied community suffer from MSDs [14]. According to a survey conducted by Sarwar et al., most dentists experience MSDs, with pain being the most common complaint [15]. Musculoskeletal pain in individuals can arise from a combination of internal factors, including age, genetics, obesity, and mental stress, as well as external factors, such as repetitive movements, prolonged static positions, poor lighting conditions, and incorrect positioning of the dentist or patient [16].

Many disorders and diseases that occur in the workplace have specific reasons, including a lack of knowledge about how to perform work correctly and a failure to apply ergonomic principles. Eskandari Nasab et al. in their study showed that both face-to-face and non-face-to-face training reduce ergonomic risk factors and musculoskeletal complaints in the studied subjects. The results indicated that the impact of face-to-face training was significantly greater than that of non-face-to-face training [17]. A study conducted by Bahrami et al. demonstrated a significant difference in the occurrence of MSDs in the neck, elbow, and shoulder among administrative staff in hospitals, after the implementation of ergonomic training programs [18]. Abdollahi et al. reported in their study, conducted among nursing staff working in hospital operating rooms, that the prevalence of MSDs in the intervention group was significantly lower than in the control group after the ergonomics training program [19]. Also, performing appropriate sports exercises can increase the physical fitness and reduce MSDs. A study conducted by Yao et al. demonstrated that the prevalence of MSDs was lower in nurses who exercised compared to those who did not [20]. Additionally, Cento et al. highlighted the impact of sports exercises on reducing MSDs [21]. As MSDs have negative effects on dentists’ health and an indirect effect on the quality of health services provided to patients, increasing their awareness of ergonomic issues, in addition to helping them maintain their health, can play a crucial role in providing dental services to the general public.

Despite the existence of numerous studies on the positive effects of ergonomics, more evidence is needed to convince dentists and policymakers to adopt and implement ergonomic interventions in the workplace. By providing more evidence on the effectiveness of ergonomic interventions for dentists, this study can help promote and improve the health and well-being of these individuals. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effects of educational and exercise interventions on reducing cervical and lumbar spine pain in dentists.

Materials and Methods

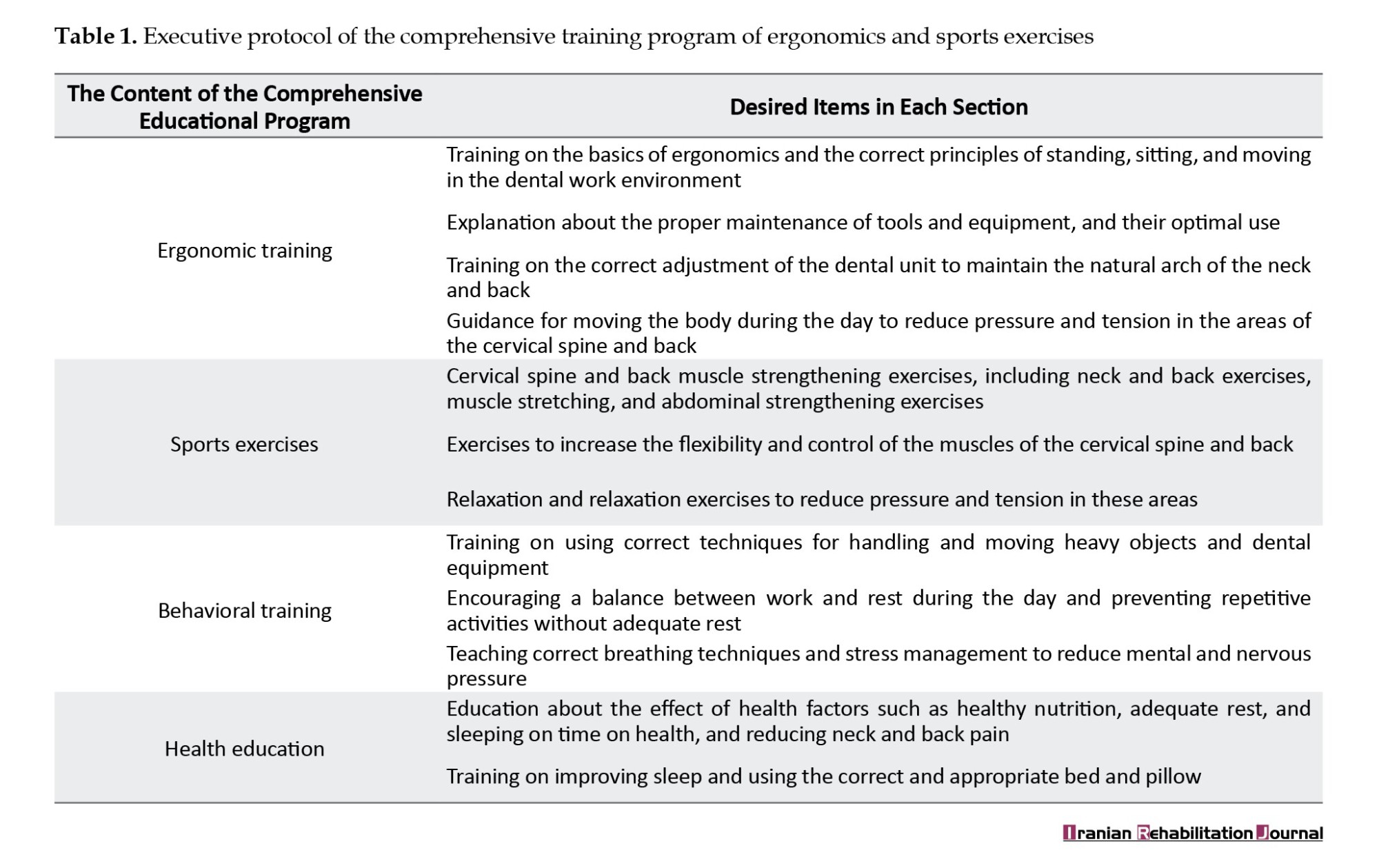

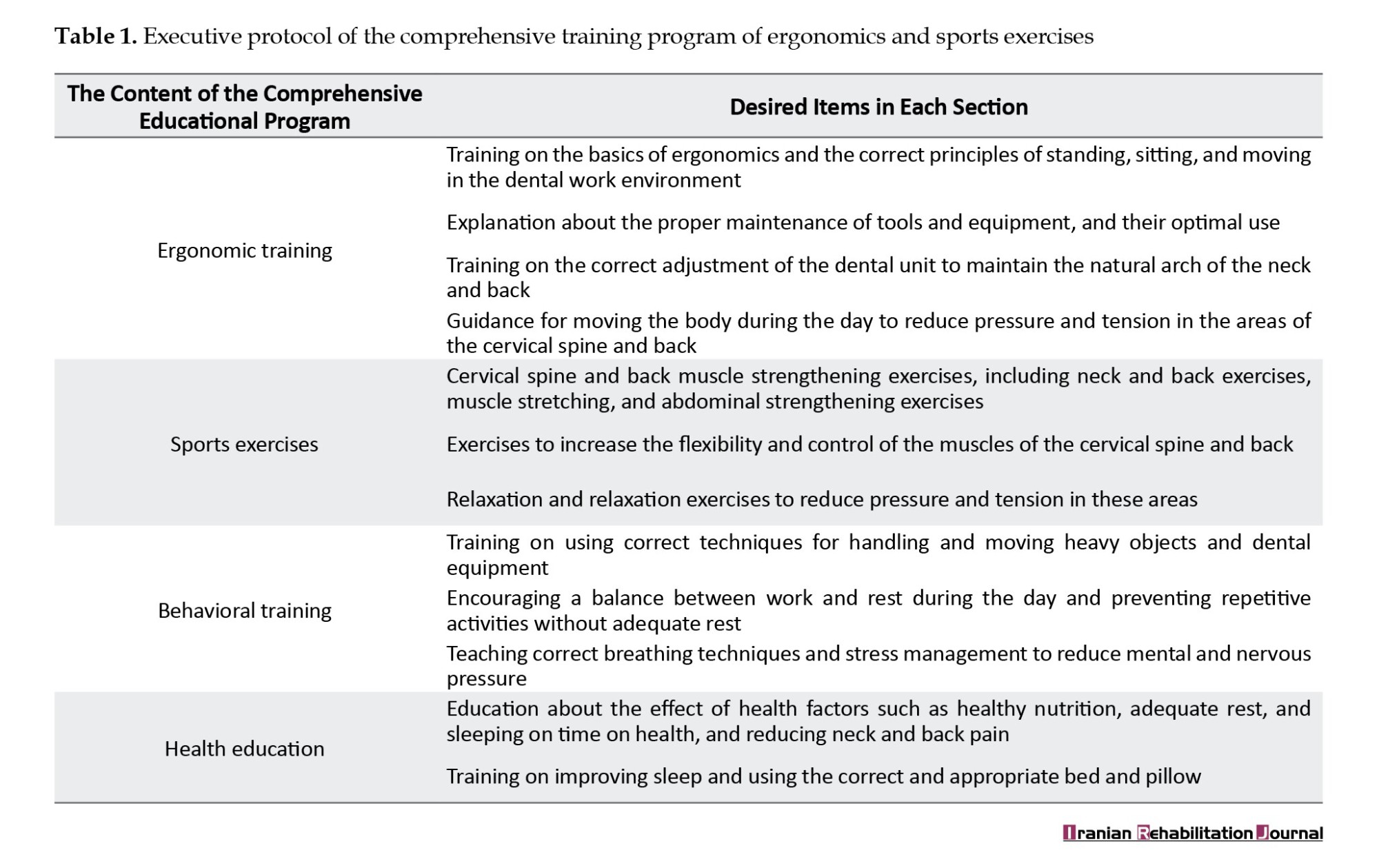

This interventional study was conducted among dentists in the clinics of Tehran University of Medical Sciences in 2022 (Table 1). After obtaining the list of these clinics, considering a significance level of 0.05, a study power of 95%, and detecting five units of pain intensity, along with four units of standard deviation, 100 dentists were selected as the statistical population. After determining the exclusion criteria, such as not voluntarily participating in the study, having underlying diseases, and having spinal cord injuries and back fractures, 81 people were selected as the statistical population. This study focused on a diverse population of dentists working in 11 different departments, including general dentistry, maxillofacial surgery, prosthetics, restorative dentistry, orthodontics, pediatric dentistry, radiology, endodontics, pathology, and oral and dental diseases. Data were collected by visiting the dentists’ workplaces in person at times that did not interfere with their work activities.

The neck disability index questionnaire, which is the most reliable tool for assessing neck disability, was used to evaluate pain status and individual performance [22, 23]. The questionnaire contained 10 questions with six options. Each item is numbered between zero and five, with higher numbers indicating greater pain. The intensity of disability is 0-20% mild, 20-41% moderate, 41-60% severe, 61-80% disabled and 81-100% severely disabled. This questionnaire has high validity and reliability; therefore, the Cronbach’s α coefficient is 0.88, and its intragroup correlation coefficient ranges from 0.90 to 0.97 [24]. The Oswestry disability index was used to assess the severity of back pain. This measure has been confirmed in previous studies to accurately gauge the level of back pain, with a reported reliability of 0.84. Thus, a score of 0 indicates complete health, 0-25 mild, 25-50 moderate, 50-75 severe, and 75-100 severe disability [25].

Next, the visual analog scale (VAS) for pain intensity was used. Using this scale, the participants selected the areas of the body (neck and back in this study) that had been painful in the last 12 months, and the intensity of pain was determined based on a scale of 10. On this scale, zero indicates no pain and 10 indicates the highest pain level. According to the results obtained from the previous sections and awareness of the existence of MSDs (back and neck pain) in people, the need for educational interventions was felt. The desired items in each section of the comprehensive educational program are listed below:

After the 6-month ergonomic intervention, the participants’ neck and back pain were re-evaluated using disability indices and a pain intensity scale. Statistical tests were used to assess changes in pain before and after the educational intervention. This analysis helped determine the effectiveness of the intervention in reducing neck and back pain. The collected data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 22. The analysis was conducted at two levels: Descriptive and analytical statistics. Descriptive statistics was used to calculate the frequency, Mean±SD of the data, which were then presented in dedicated tables. Analytical statistics included the use of paired t-tests to assess the effectiveness and significance of ergonomic interventions. Additionally, multivariate linear regression was used to consider the role of possible confounding variables, and P<0.05 was considered significant at all stages of the study.

Results

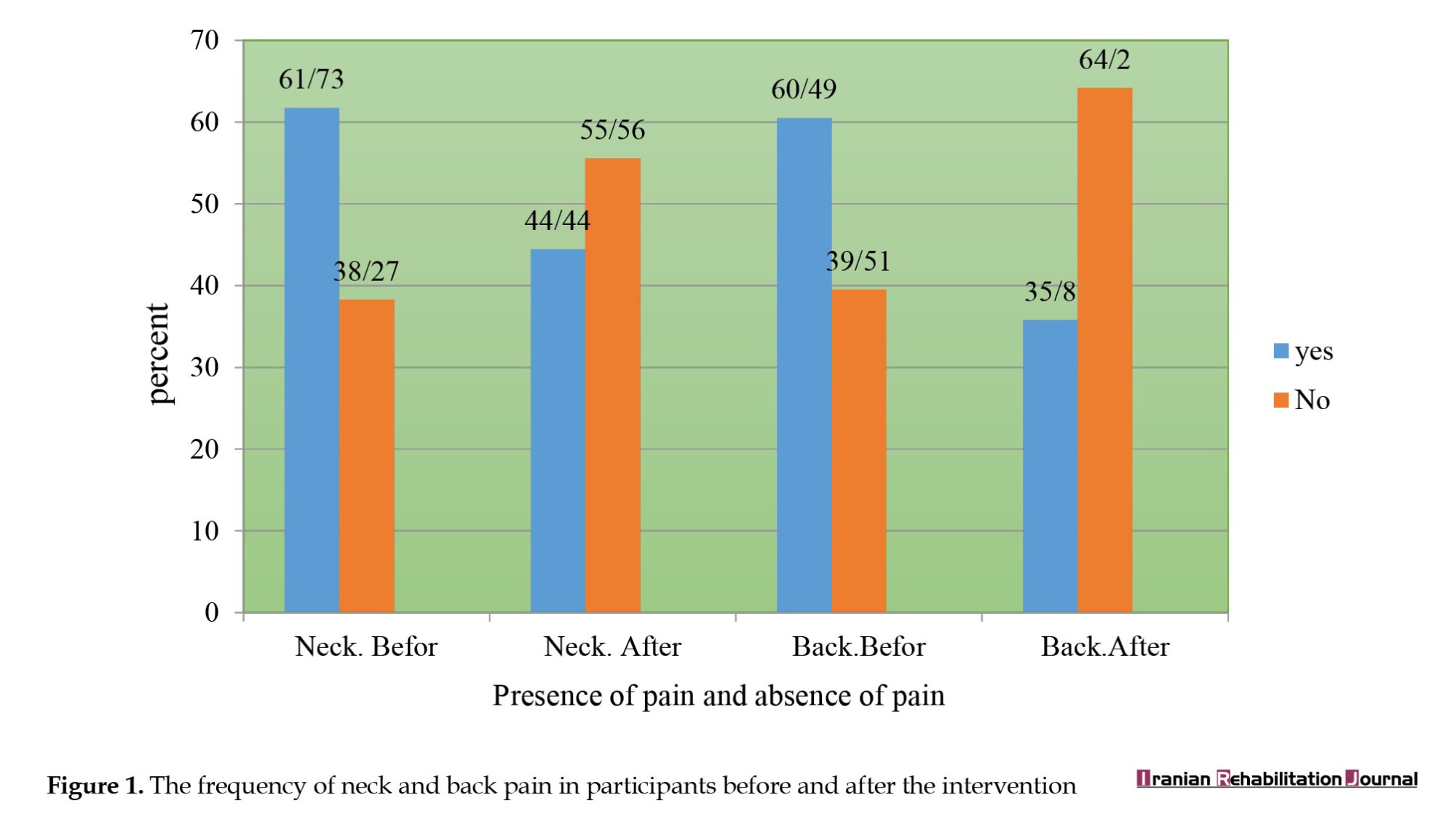

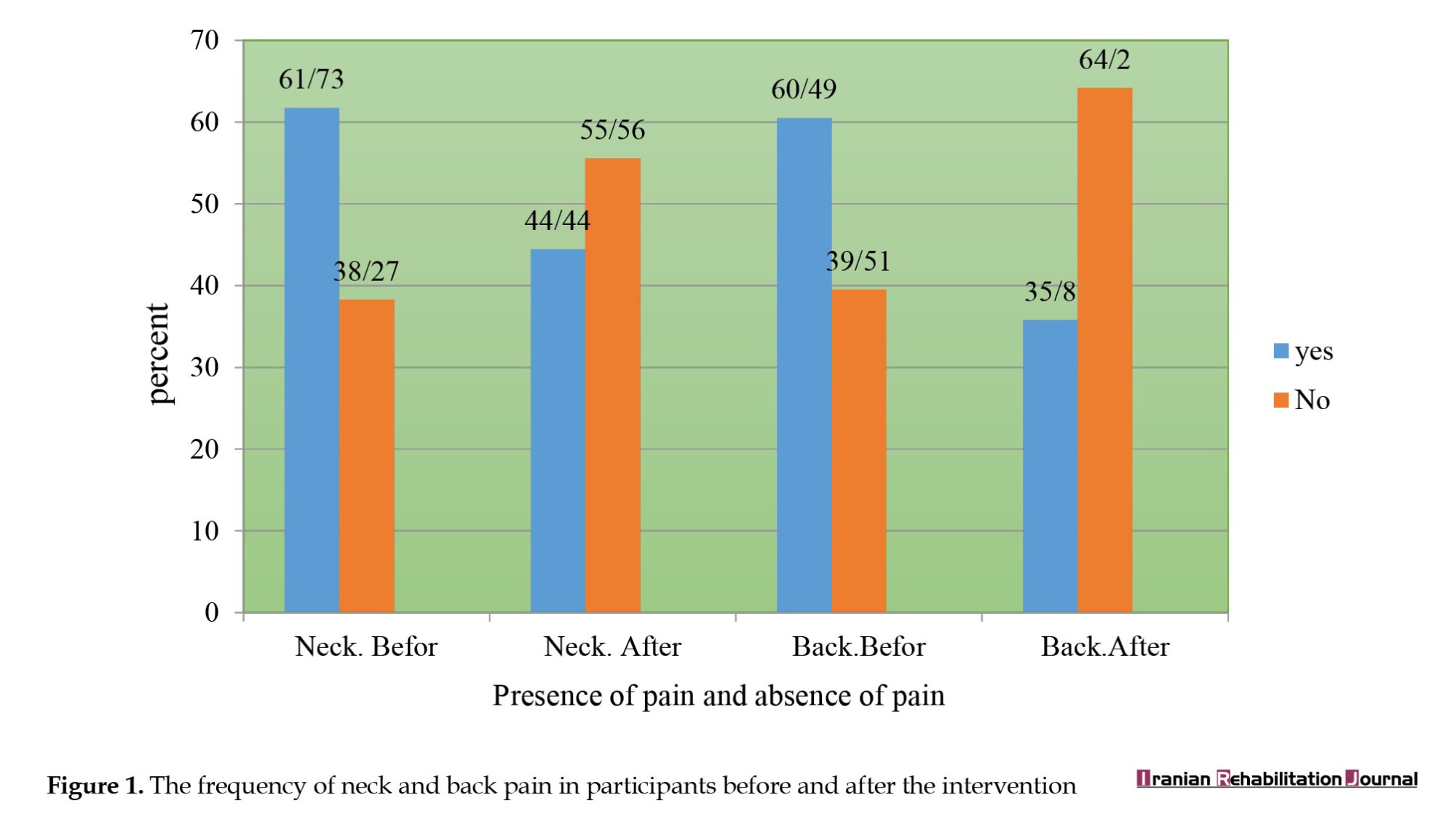

The study included 81 dentists with a Mean±SD working experience of 3.14±1.58 years from clinics covered by medical sciences universities in Tehran City. Among the participants, 32(39.5%) were male and 49(60.5%) were female. Figure 1 shows the frequency of back and neck pain among study participants before and after the intervention. According to the results shown in Figure 1, more than half of the participants had MSDs in the neck and back area before the intervention. However, the number decreased significantly after the ergonomic interventions (P<0.05).

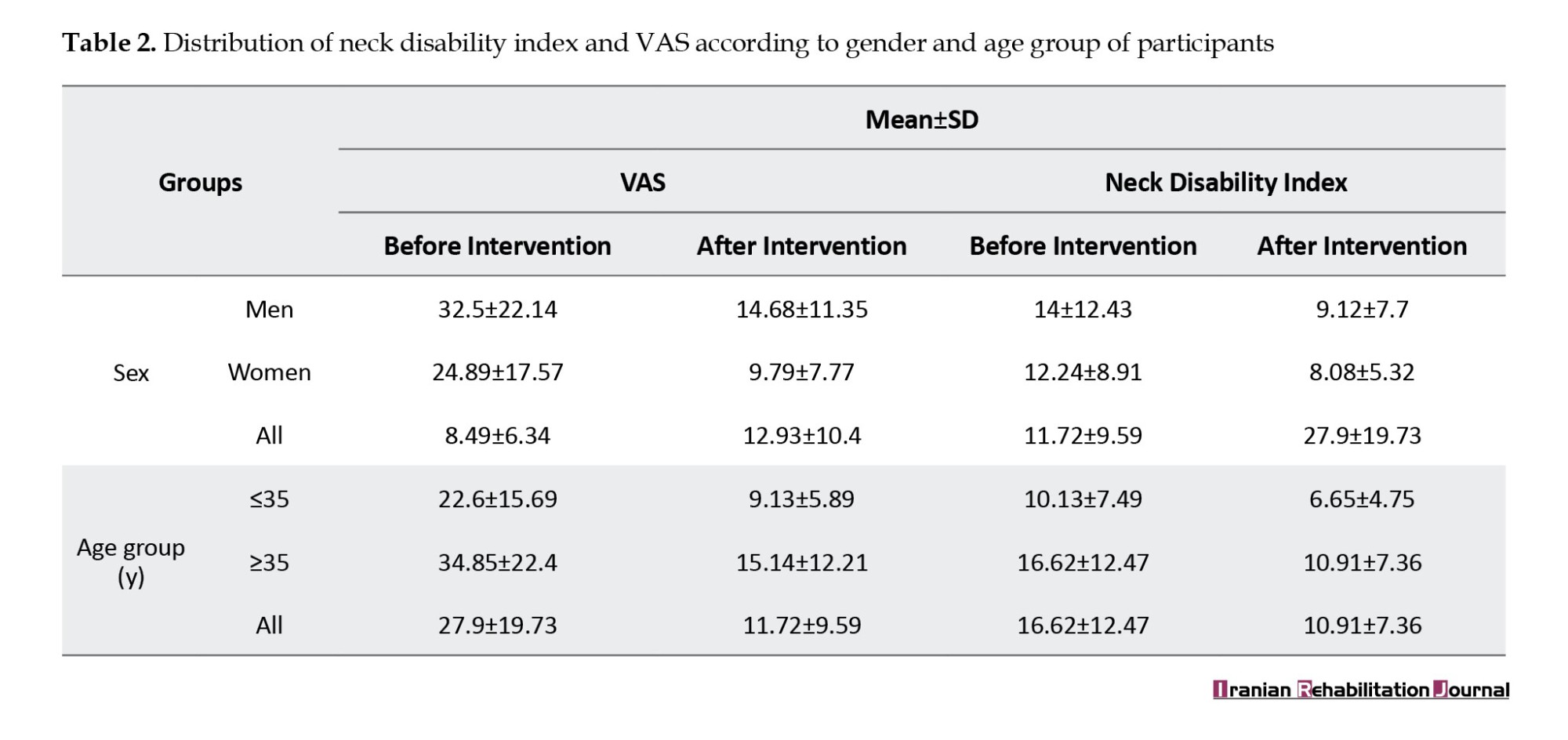

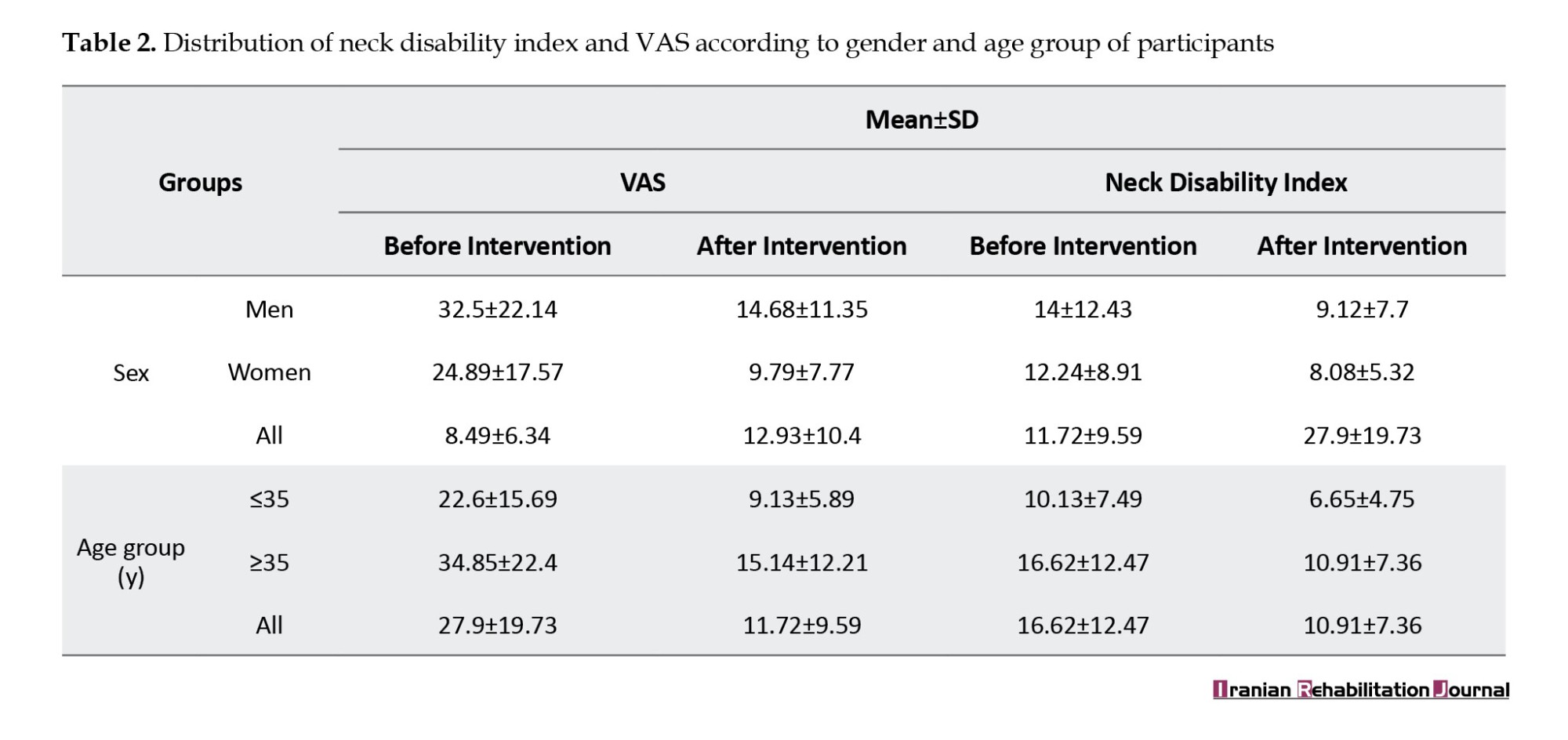

Table 2 presents the results of the distribution of neck disability index and VAS according to sex and age groups in the studied subjects. Based on the results, the average index of neck disability and VAS in both men and women decreased significantly after the intervention, resulting in an average VAS of 19.73 before the intervention and 9.59 after the intervention. Also, the average neck disability was reduced from 10.4 before the intervention to 6.34 after the intervention. This decrease was observed in different age groups.

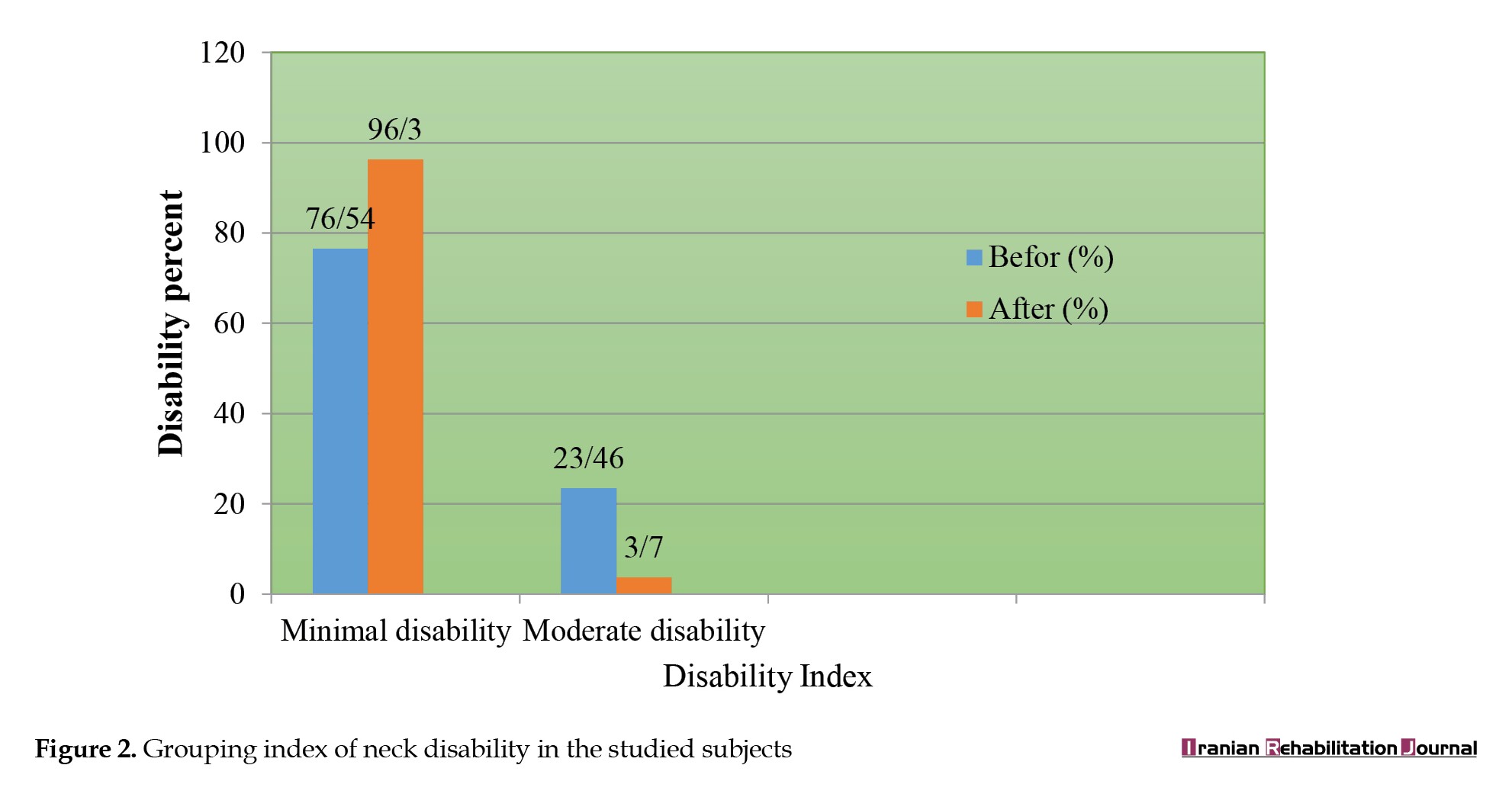

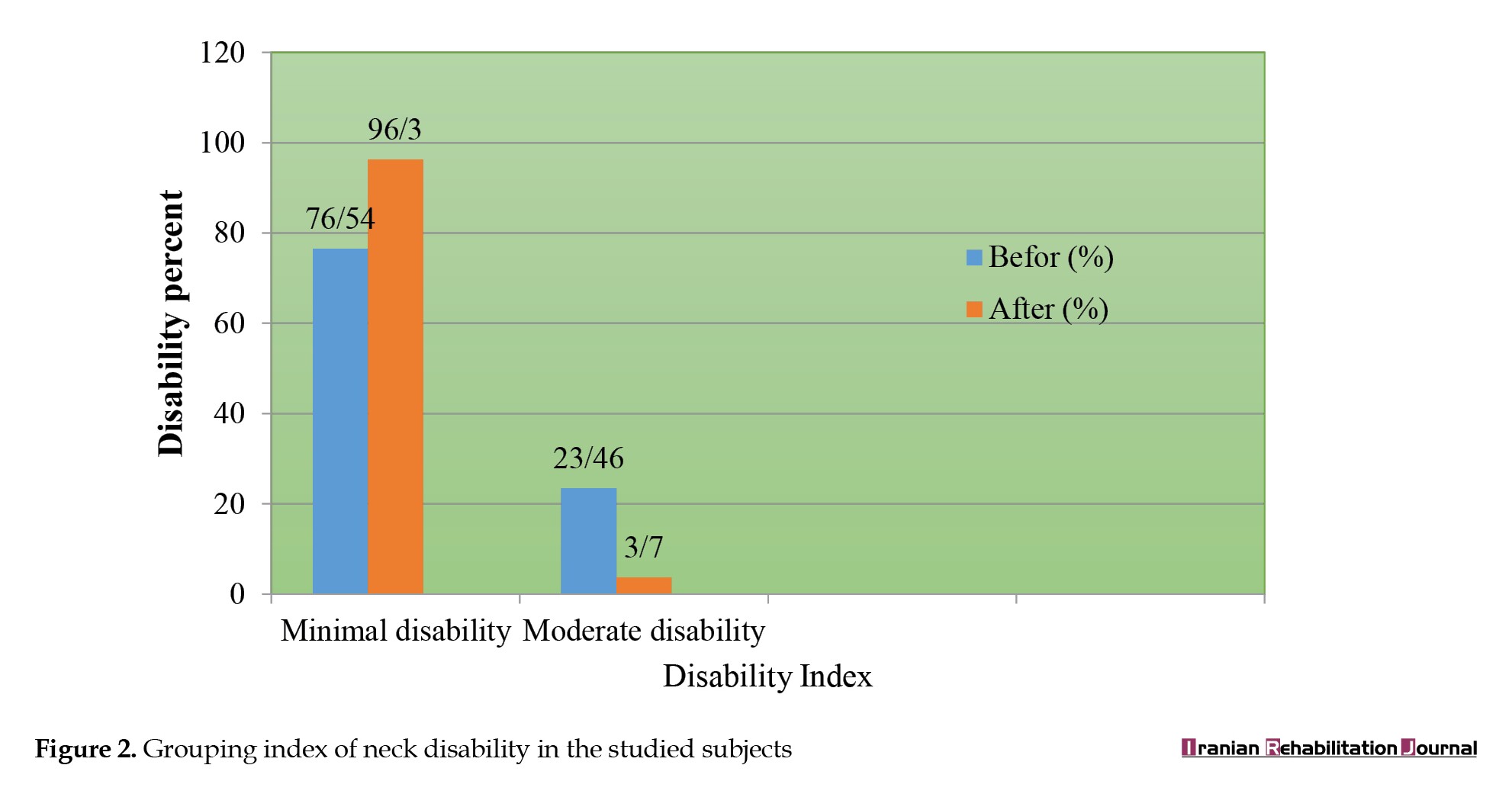

Figure 2 shows that the interventions led to a decrease in medium disability and an increase in the low-risk category, indicating positive outcomes for participants’ musculoskeletal health.

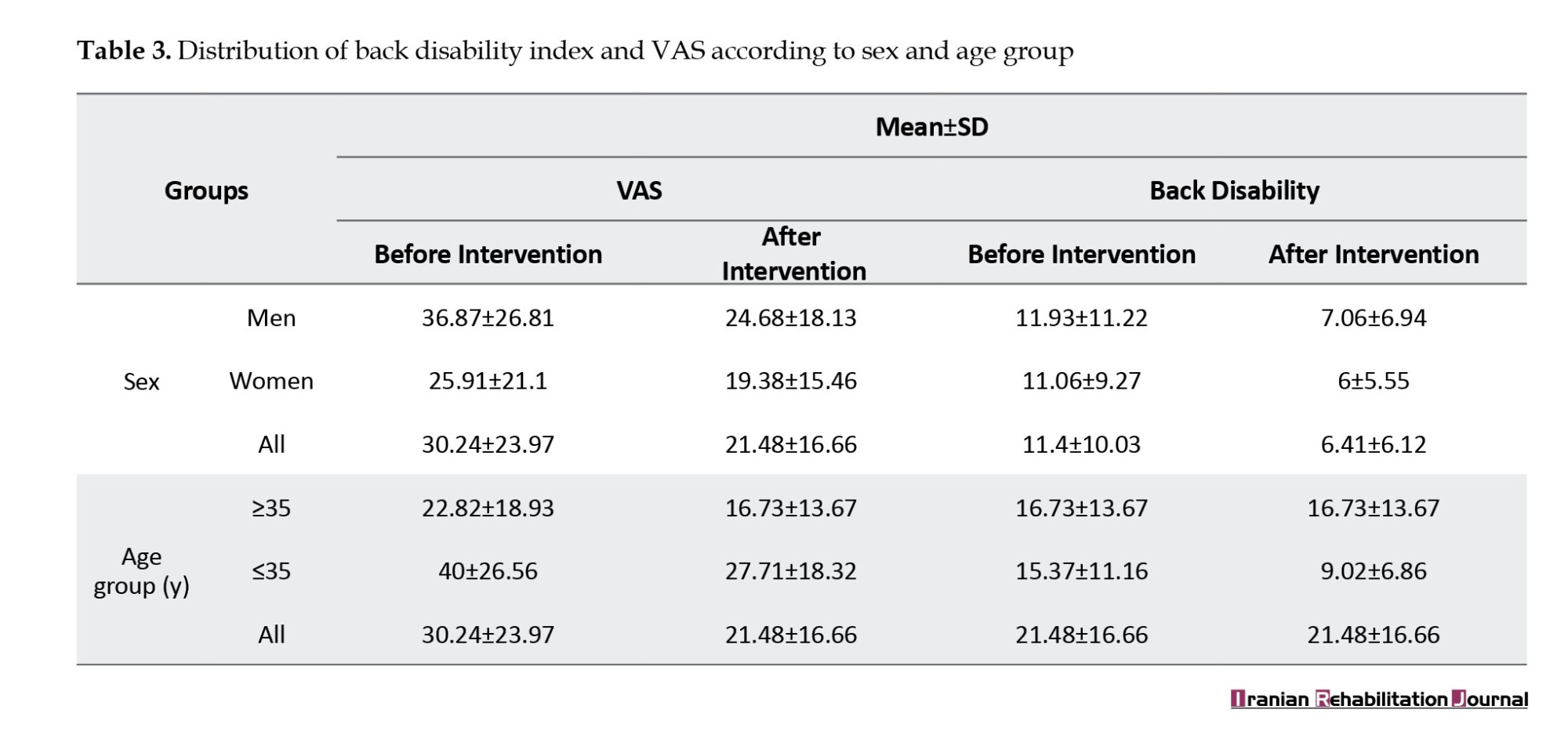

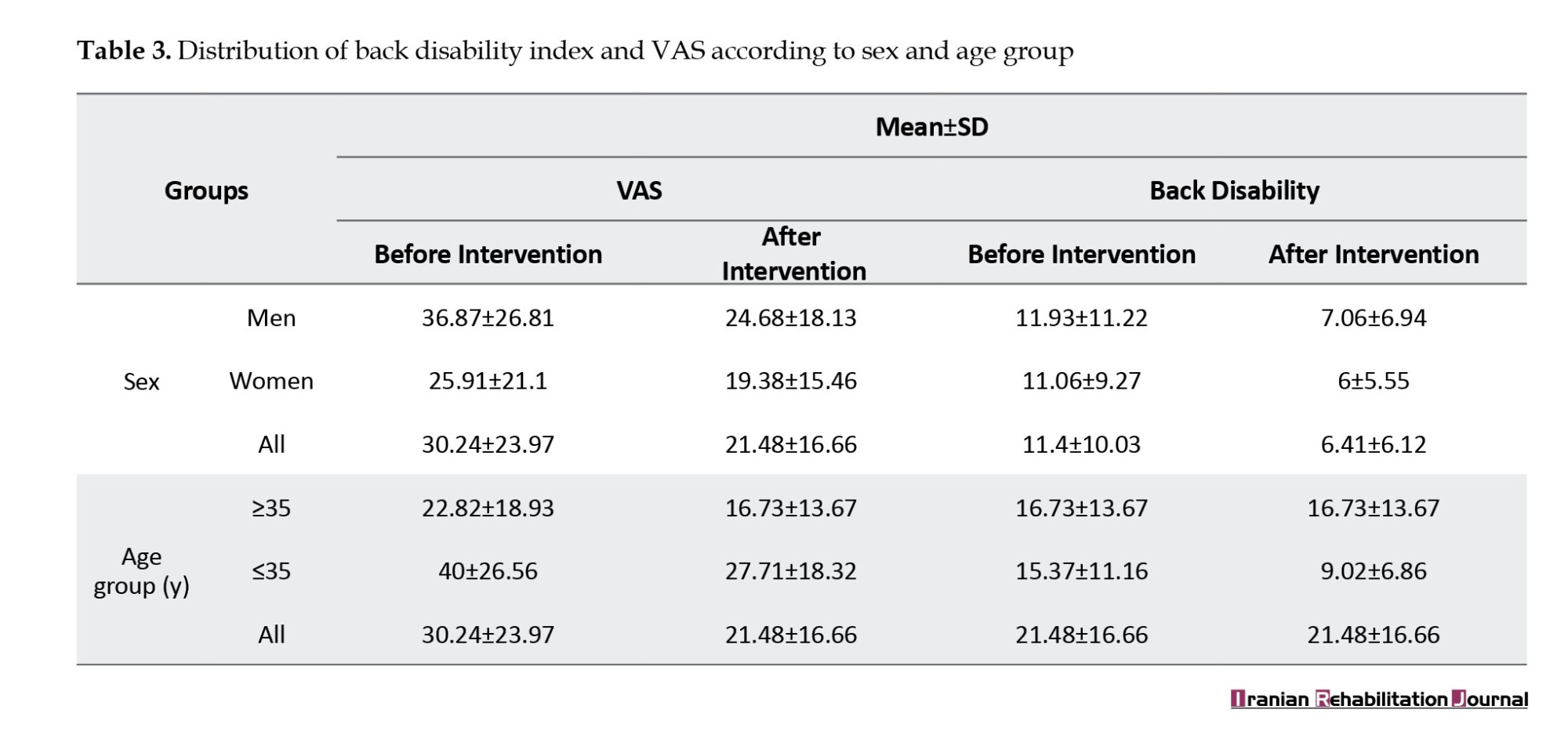

Table 3 presents the MSD results for the lower back. The average distribution of the back disability index and VAS scores in all study participants, categorized by sex and age groups, demonstrated a significant decrease after the ergonomic interventions compared to the pre-intervention period (P<0.05).

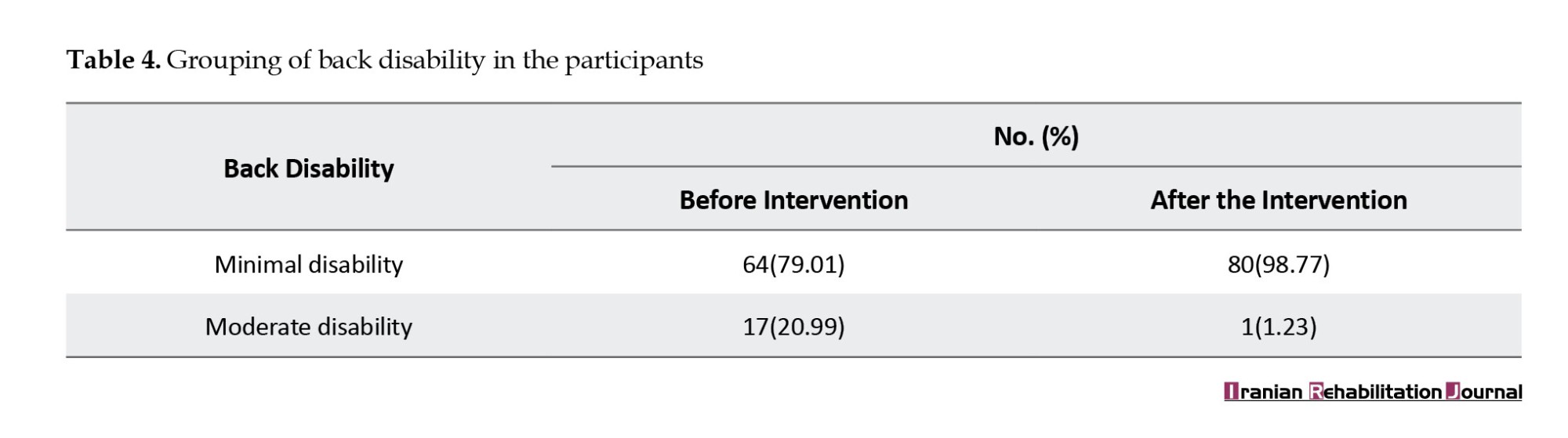

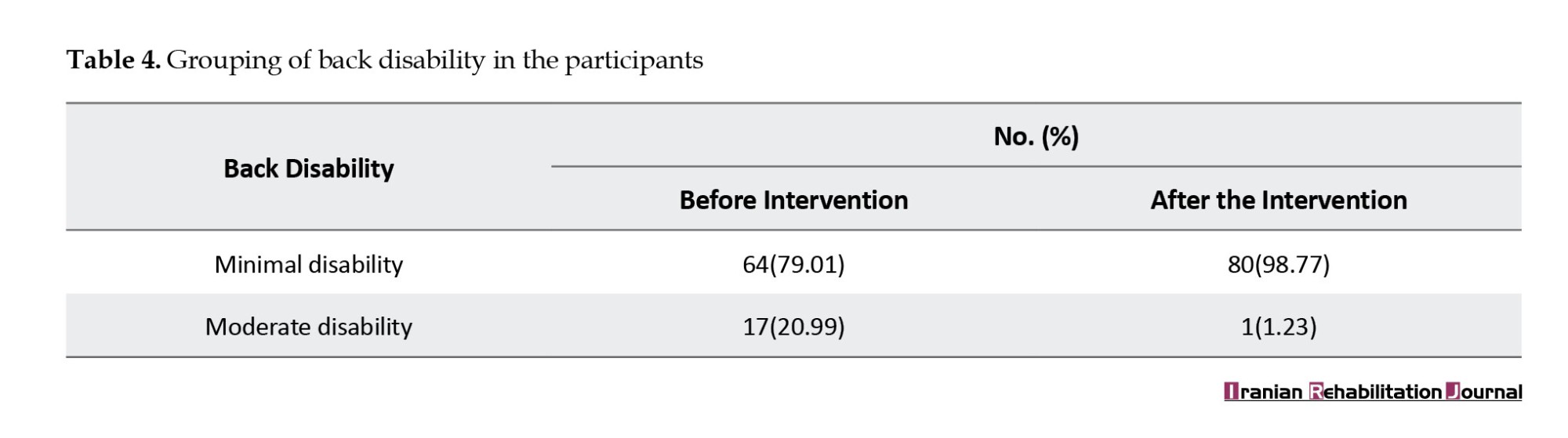

According to the results in Table 3, the average distribution of the back disability index and VAS scores among all participants, categorized by age and age groups, significantly decreased after the ergonomic interventions compared to before the interventions. Table 4 presents the distribution of disability severity among the participants.

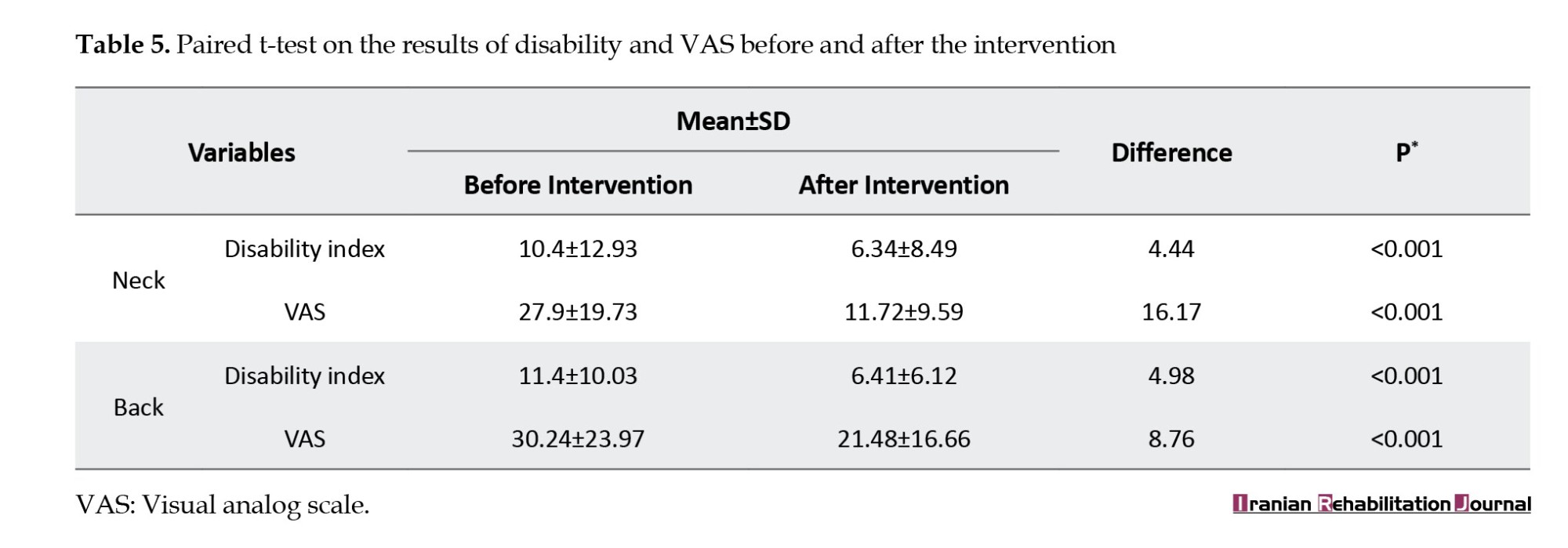

Based on Table 4, it can be concluded that the distribution of participants was influenced by the training and interventions, as evidenced by the large percentage of people in the minimal disability group after the interventions. In the following, a paired t-test was performed on the data obtained in Table 5, allowing for the observation of the impact of educational interventions at a significant level (P<0.05).

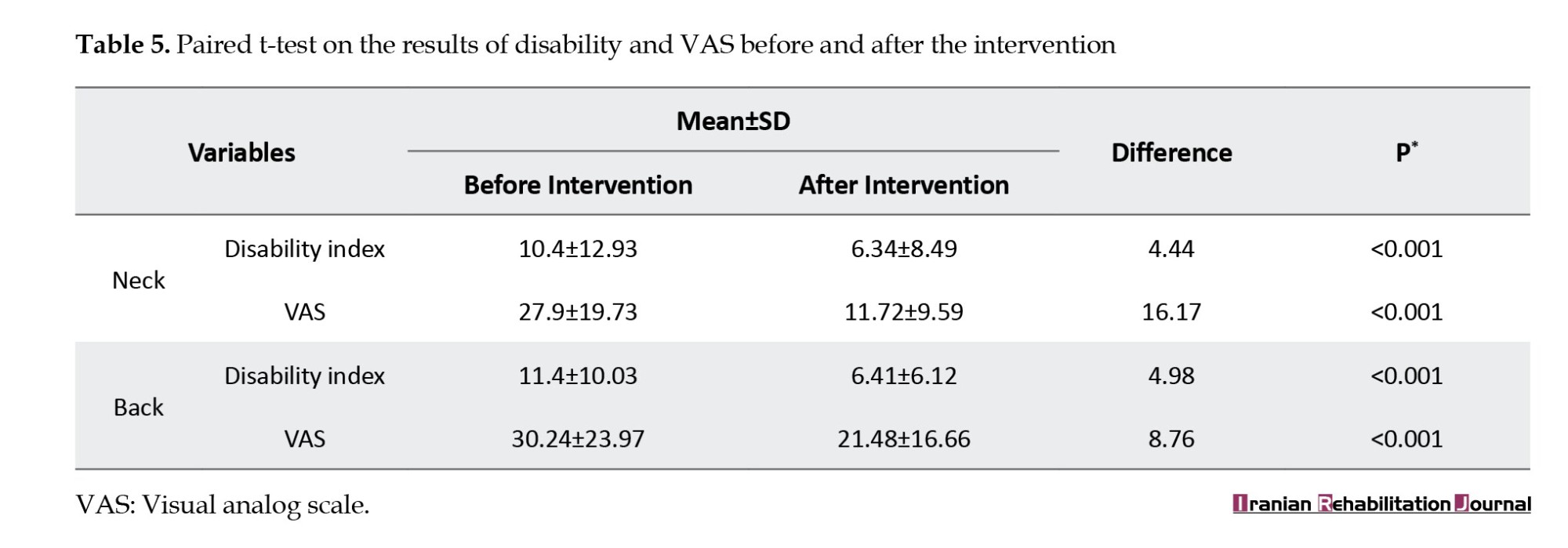

The results of the paired t-test showed that the interventions (education and exercise) were significantly effective, resulting in a decrease of 4.44 points in the neck disability index level and 16.17 points in the VAS level (P<0.001). Also, the reduction in waist circumference for the disability index was 4.98, and for the VAS value, it was 8.76 (P<0.001).

Discussion

While providing oral and dental health services to their patients, dentists face challenges, such as performing continuous and accurate work on the teeth, maintaining a proper body position for extended periods, and enduring mental stress and pressure. Using heavy and large tools, sitting in an improper position, and a lack of continuous movement may cause MSDs, including pain in the spine, back, neck, and shoulders.

The results of this study showed that the prevalence of neck and back pain among dentists is high. Alotaibi et al. showed in their study that neck and back pain are among the most common MSDs in dentists, and to reduce pain and disorders, ergonomic training is necessary [11]. Tariq et al. in their study showed that dentists in Faisalabad are prone to neck pain due to poor working conditions [26]. Also, Ajwa et al. showed in their study that back pain is the most common MSD among dentists, with a significant relationship to the sitting position [27]. Ohlendorf et al. reported a high prevalence of MSDs in the neck, shoulder, and back among dentists in their research [9].

This study also revealed a correlation between age and the prevalence of back and neck pain among dentists. The results indicated that older individuals had a higher average distribution of pain and discomfort compared to younger individuals, which can be explained by the fact that MSDs are chronic pain and show themselves with increasing age and work experience in more people. This result is consistent with those of previous studies. Holmström et al. showed in their study that the incidence of MSDs increases with age [28]. In a study by Ahmadi Motemayel et al. titled “the prevalence of MSDs among general dentists in Hamedan City, Iran,” a significant relationship between age and MSDs was observed [29]. Similarly, Putri et al. found a significant correlation between age and MSD-related complaints [30]. Heidari et al. in their study on work-related MSDs among nurses, reported similar findings, indicating a significant association between age and the prevalence of MSDs [31]. These studies support the current study’s results, highlighting the relationship between age and the prevalence of MSDs. In a study conducted by Rokni et al. among nurses in Sari City, Iran, the highest expression of musculoskeletal discomfort was observed in the lower back, knee, ankle, and neck regions among the nursing staff. A significant statistical relationship was found between employees’ age and weekly working hours and MSDs in the lower back area [32].

The analytical findings of the study highlight the significant effect of ergonomic interventions (training and sports exercises) in reducing MSDs in both the neck and back. This outcome is valuable for reducing pain and discomfort, and numerous studies in the field support it. For instance, Jari et al. showed that educational interventions can reduce MSDs [33]. Sowah et al. provided evidence of the effectiveness of exercise with or without educational interventions in the prevention of LBP [34]. Ebrahimi et al. conducted a study titled “examining the effect of ergonomic training programs on the prevalence of MSDs in the administrative and support staff of Imam Reza Hospital in Mashhad City, Iran.” The results demonstrated that teaching ergonomic principles effectively reduced the risk of MSDs among employees who extensively used computer systems [35]. Bolghanabadi et al. highlighted the effectiveness of educational interventions and activity rotation in reducing MSDs [36]. Sohrabi et al. emphasized the effective role of ergonomic interventions in reducing MSDs and suggested holding continuous training courses to control ergonomic risk factors [37]. In a study conducted by Omi Kalteh et al. titled “the effect of an ergonomic training program on the reduction of musculoskeletal injury factors,” the authors reported that the implementation of ergonomic training programs can be an effective approach to reducing MSDs [38]. Sundstrup et al. demonstrated that exercise and strength training at work can reduce MSDs among physically demanding workers [39]. Similarly, Gwinnutt et al. have shown the effectiveness of exercise and physical activity in individuals with musculoskeletal and rheumatic diseases. In a similar study, Serra et al. [40] also showed that engaging in sports and exercise at the workplace is a potential way to reduce MSDs among individuals [41].

Conclusion

Based on the results of this study, ergonomic control and intervention measures, including training on ergonomic issues and appropriate sports exercises, can be effective in reducing disorders and disabilities in dentists.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.SBMU.PHNS.REC.1399.134).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Data collection: Mahdis Sobhanian; Validation: Mohammad Hosein Vaziri and Ali Salehi Sahlabadi; Writing the original draft: Vafa Feyzi and Zohreh Ahangari; Review and editing: Fahimeh Vaziri and Mohammad Mohsen Roostayi; Final approval: Ali Salehi Sahlabadi; Conceptualization, methodology, and investigation: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all those who helped and supported the preparation of this article.

References

Ergonomics is a science that deals with the interaction between humans and their environment and is used to design work environments that increase human well-being and system performance [1]. Ergonomics encompasses all aspects of the work environment, and the physical aspects of the workplace directly influence various factors, including productivity, health, safety, comfort, job satisfaction, and overall morale [2]. The ergonomic conditions of individuals and their surroundings are of significant importance [3]. Therefore, in the case of non-conformity, musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) and discomfort occur in people, which are one of the main causes of disability worldwide and a significant increase in social costs [4].

MSDs refer to injuries and diseases affecting different parts of the body that are caused or exacerbated by manual handling, prolonged standing, and poor posture [5, 6]. Work-related MSDs in the lower limbs, especially in the lower back and knees, were more prevalent than other similar studies in Iran [7]. If it continues, it causes physical and emotional fatigue, and job burnout, which is considered a significant issue among health service providers [8]. According to the nature and working conditions, the dental profession requires an inappropriate body posture, which includes bending the head and neck forward and sideways, as well as tilting and turning the trunk towards the patient, thereby putting pressure on the musculoskeletal system [9].

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) MSD, neck pain is a crucial occupational health issue in the field of dentistry [10]. Alotaibi et al. showed that neck and back pain are the most common among dentists [11]. MSDs in the dental profession among Iranian dentists are a serious issue, and studies conducted in this field can be cited. In a study by Harris et al. conducted in Canada, 83% of dentists had MSDs [12]. Roozegar et al reported a high prevalence of such disorders [13]. Sedaghati et al also reported similar results in their study, and half of the dentists in the studied community suffer from MSDs [14]. According to a survey conducted by Sarwar et al., most dentists experience MSDs, with pain being the most common complaint [15]. Musculoskeletal pain in individuals can arise from a combination of internal factors, including age, genetics, obesity, and mental stress, as well as external factors, such as repetitive movements, prolonged static positions, poor lighting conditions, and incorrect positioning of the dentist or patient [16].

Many disorders and diseases that occur in the workplace have specific reasons, including a lack of knowledge about how to perform work correctly and a failure to apply ergonomic principles. Eskandari Nasab et al. in their study showed that both face-to-face and non-face-to-face training reduce ergonomic risk factors and musculoskeletal complaints in the studied subjects. The results indicated that the impact of face-to-face training was significantly greater than that of non-face-to-face training [17]. A study conducted by Bahrami et al. demonstrated a significant difference in the occurrence of MSDs in the neck, elbow, and shoulder among administrative staff in hospitals, after the implementation of ergonomic training programs [18]. Abdollahi et al. reported in their study, conducted among nursing staff working in hospital operating rooms, that the prevalence of MSDs in the intervention group was significantly lower than in the control group after the ergonomics training program [19]. Also, performing appropriate sports exercises can increase the physical fitness and reduce MSDs. A study conducted by Yao et al. demonstrated that the prevalence of MSDs was lower in nurses who exercised compared to those who did not [20]. Additionally, Cento et al. highlighted the impact of sports exercises on reducing MSDs [21]. As MSDs have negative effects on dentists’ health and an indirect effect on the quality of health services provided to patients, increasing their awareness of ergonomic issues, in addition to helping them maintain their health, can play a crucial role in providing dental services to the general public.

Despite the existence of numerous studies on the positive effects of ergonomics, more evidence is needed to convince dentists and policymakers to adopt and implement ergonomic interventions in the workplace. By providing more evidence on the effectiveness of ergonomic interventions for dentists, this study can help promote and improve the health and well-being of these individuals. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effects of educational and exercise interventions on reducing cervical and lumbar spine pain in dentists.

Materials and Methods

This interventional study was conducted among dentists in the clinics of Tehran University of Medical Sciences in 2022 (Table 1). After obtaining the list of these clinics, considering a significance level of 0.05, a study power of 95%, and detecting five units of pain intensity, along with four units of standard deviation, 100 dentists were selected as the statistical population. After determining the exclusion criteria, such as not voluntarily participating in the study, having underlying diseases, and having spinal cord injuries and back fractures, 81 people were selected as the statistical population. This study focused on a diverse population of dentists working in 11 different departments, including general dentistry, maxillofacial surgery, prosthetics, restorative dentistry, orthodontics, pediatric dentistry, radiology, endodontics, pathology, and oral and dental diseases. Data were collected by visiting the dentists’ workplaces in person at times that did not interfere with their work activities.

The neck disability index questionnaire, which is the most reliable tool for assessing neck disability, was used to evaluate pain status and individual performance [22, 23]. The questionnaire contained 10 questions with six options. Each item is numbered between zero and five, with higher numbers indicating greater pain. The intensity of disability is 0-20% mild, 20-41% moderate, 41-60% severe, 61-80% disabled and 81-100% severely disabled. This questionnaire has high validity and reliability; therefore, the Cronbach’s α coefficient is 0.88, and its intragroup correlation coefficient ranges from 0.90 to 0.97 [24]. The Oswestry disability index was used to assess the severity of back pain. This measure has been confirmed in previous studies to accurately gauge the level of back pain, with a reported reliability of 0.84. Thus, a score of 0 indicates complete health, 0-25 mild, 25-50 moderate, 50-75 severe, and 75-100 severe disability [25].

Next, the visual analog scale (VAS) for pain intensity was used. Using this scale, the participants selected the areas of the body (neck and back in this study) that had been painful in the last 12 months, and the intensity of pain was determined based on a scale of 10. On this scale, zero indicates no pain and 10 indicates the highest pain level. According to the results obtained from the previous sections and awareness of the existence of MSDs (back and neck pain) in people, the need for educational interventions was felt. The desired items in each section of the comprehensive educational program are listed below:

After the 6-month ergonomic intervention, the participants’ neck and back pain were re-evaluated using disability indices and a pain intensity scale. Statistical tests were used to assess changes in pain before and after the educational intervention. This analysis helped determine the effectiveness of the intervention in reducing neck and back pain. The collected data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 22. The analysis was conducted at two levels: Descriptive and analytical statistics. Descriptive statistics was used to calculate the frequency, Mean±SD of the data, which were then presented in dedicated tables. Analytical statistics included the use of paired t-tests to assess the effectiveness and significance of ergonomic interventions. Additionally, multivariate linear regression was used to consider the role of possible confounding variables, and P<0.05 was considered significant at all stages of the study.

Results

The study included 81 dentists with a Mean±SD working experience of 3.14±1.58 years from clinics covered by medical sciences universities in Tehran City. Among the participants, 32(39.5%) were male and 49(60.5%) were female. Figure 1 shows the frequency of back and neck pain among study participants before and after the intervention. According to the results shown in Figure 1, more than half of the participants had MSDs in the neck and back area before the intervention. However, the number decreased significantly after the ergonomic interventions (P<0.05).

Table 2 presents the results of the distribution of neck disability index and VAS according to sex and age groups in the studied subjects. Based on the results, the average index of neck disability and VAS in both men and women decreased significantly after the intervention, resulting in an average VAS of 19.73 before the intervention and 9.59 after the intervention. Also, the average neck disability was reduced from 10.4 before the intervention to 6.34 after the intervention. This decrease was observed in different age groups.

Figure 2 shows that the interventions led to a decrease in medium disability and an increase in the low-risk category, indicating positive outcomes for participants’ musculoskeletal health.

Table 3 presents the MSD results for the lower back. The average distribution of the back disability index and VAS scores in all study participants, categorized by sex and age groups, demonstrated a significant decrease after the ergonomic interventions compared to the pre-intervention period (P<0.05).

According to the results in Table 3, the average distribution of the back disability index and VAS scores among all participants, categorized by age and age groups, significantly decreased after the ergonomic interventions compared to before the interventions. Table 4 presents the distribution of disability severity among the participants.

Based on Table 4, it can be concluded that the distribution of participants was influenced by the training and interventions, as evidenced by the large percentage of people in the minimal disability group after the interventions. In the following, a paired t-test was performed on the data obtained in Table 5, allowing for the observation of the impact of educational interventions at a significant level (P<0.05).

The results of the paired t-test showed that the interventions (education and exercise) were significantly effective, resulting in a decrease of 4.44 points in the neck disability index level and 16.17 points in the VAS level (P<0.001). Also, the reduction in waist circumference for the disability index was 4.98, and for the VAS value, it was 8.76 (P<0.001).

Discussion

While providing oral and dental health services to their patients, dentists face challenges, such as performing continuous and accurate work on the teeth, maintaining a proper body position for extended periods, and enduring mental stress and pressure. Using heavy and large tools, sitting in an improper position, and a lack of continuous movement may cause MSDs, including pain in the spine, back, neck, and shoulders.

The results of this study showed that the prevalence of neck and back pain among dentists is high. Alotaibi et al. showed in their study that neck and back pain are among the most common MSDs in dentists, and to reduce pain and disorders, ergonomic training is necessary [11]. Tariq et al. in their study showed that dentists in Faisalabad are prone to neck pain due to poor working conditions [26]. Also, Ajwa et al. showed in their study that back pain is the most common MSD among dentists, with a significant relationship to the sitting position [27]. Ohlendorf et al. reported a high prevalence of MSDs in the neck, shoulder, and back among dentists in their research [9].

This study also revealed a correlation between age and the prevalence of back and neck pain among dentists. The results indicated that older individuals had a higher average distribution of pain and discomfort compared to younger individuals, which can be explained by the fact that MSDs are chronic pain and show themselves with increasing age and work experience in more people. This result is consistent with those of previous studies. Holmström et al. showed in their study that the incidence of MSDs increases with age [28]. In a study by Ahmadi Motemayel et al. titled “the prevalence of MSDs among general dentists in Hamedan City, Iran,” a significant relationship between age and MSDs was observed [29]. Similarly, Putri et al. found a significant correlation between age and MSD-related complaints [30]. Heidari et al. in their study on work-related MSDs among nurses, reported similar findings, indicating a significant association between age and the prevalence of MSDs [31]. These studies support the current study’s results, highlighting the relationship between age and the prevalence of MSDs. In a study conducted by Rokni et al. among nurses in Sari City, Iran, the highest expression of musculoskeletal discomfort was observed in the lower back, knee, ankle, and neck regions among the nursing staff. A significant statistical relationship was found between employees’ age and weekly working hours and MSDs in the lower back area [32].

The analytical findings of the study highlight the significant effect of ergonomic interventions (training and sports exercises) in reducing MSDs in both the neck and back. This outcome is valuable for reducing pain and discomfort, and numerous studies in the field support it. For instance, Jari et al. showed that educational interventions can reduce MSDs [33]. Sowah et al. provided evidence of the effectiveness of exercise with or without educational interventions in the prevention of LBP [34]. Ebrahimi et al. conducted a study titled “examining the effect of ergonomic training programs on the prevalence of MSDs in the administrative and support staff of Imam Reza Hospital in Mashhad City, Iran.” The results demonstrated that teaching ergonomic principles effectively reduced the risk of MSDs among employees who extensively used computer systems [35]. Bolghanabadi et al. highlighted the effectiveness of educational interventions and activity rotation in reducing MSDs [36]. Sohrabi et al. emphasized the effective role of ergonomic interventions in reducing MSDs and suggested holding continuous training courses to control ergonomic risk factors [37]. In a study conducted by Omi Kalteh et al. titled “the effect of an ergonomic training program on the reduction of musculoskeletal injury factors,” the authors reported that the implementation of ergonomic training programs can be an effective approach to reducing MSDs [38]. Sundstrup et al. demonstrated that exercise and strength training at work can reduce MSDs among physically demanding workers [39]. Similarly, Gwinnutt et al. have shown the effectiveness of exercise and physical activity in individuals with musculoskeletal and rheumatic diseases. In a similar study, Serra et al. [40] also showed that engaging in sports and exercise at the workplace is a potential way to reduce MSDs among individuals [41].

Conclusion

Based on the results of this study, ergonomic control and intervention measures, including training on ergonomic issues and appropriate sports exercises, can be effective in reducing disorders and disabilities in dentists.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.SBMU.PHNS.REC.1399.134).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Data collection: Mahdis Sobhanian; Validation: Mohammad Hosein Vaziri and Ali Salehi Sahlabadi; Writing the original draft: Vafa Feyzi and Zohreh Ahangari; Review and editing: Fahimeh Vaziri and Mohammad Mohsen Roostayi; Final approval: Ali Salehi Sahlabadi; Conceptualization, methodology, and investigation: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all those who helped and supported the preparation of this article.

References

- Odebiyi DO, Arinze Chris Okafor U. Musculoskeletal disorders, workplace ergonomics and injury prevention. London: IntechOpen; 2023. [DOI:10.5772/intechopen.106031]

- Yarmohammadi H, Niksima S H, Yarmohammadi S, Khammar A, Marioryad H, Poursadeqiyan M. [Evaluating the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in drivers systematic review and meta-analysis (Persian)]. Journal of Health and Safety at Work. 2019; 9(3):221-30. [Link]

- Aghahi RH, Darabi R, Hashemipour MA. Neck, back, and shoulder pains and ergonomic factors among dental students. Journal of Education and Health Promotion. 2018; 7(1):40.[DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_80_16]

- Lind CM, Abtahi F, Forsman M. Wearable motion capture devices for the prevention of work-related musculoskeletal disorders in ergonomics-an overview of current applications, challenges, and future opportunities. Sensors. 2023; 23(9):4259. [DOI:10.3390/s23094259]

- Ayub Y, Shah ZA. Assessment of work related musculoskeletal disorders in manufacturing industry. Journal of Ergonomics. 2023; 8(3):1-5. [DOI:10.4172/2165-7556.1000233]

- Mazloumi A, Mehrdad R, Kazemi Z, Vahedi Z, Hajizade L. [Risk factors of work related musculoskeletal disorders in Iranian Workers during 2000-2015 (Persian)]. Journal of Health and Safety at Work. 2021; 11(3):395-416. [Link]

- Parno A, Sayehmiri K, Mokarami H, Parno M, Azrah K, Ebrahimi MH, et al. [The prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders in the lower limbs among Iranian workers: A meta-analysis study (Persian)]. Iran Occupational Health. 2016; 13(5):50-9. [Link]

- Nasiri E, Mahdavinoor SMM, Zadi O, Memar Bashi E, Rafiei MH. [Evaluation of usculoskeletal disorders and workplace ergonomic considerations in surgical technologists (Persian)]. Nursing and Midwifery Journal. 2020; 18(7):587-96. [DOI:10.29252/unmf.18.7.587]

- Ohlendorf D, Naser A, Haas Y, Haenel J, Fraeulin L, Holzgreve F, et al. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among dentists and dental students in Germany. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(23):8740. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17238740] [PMID]

- Kawtharani AA, Chemeisani A, Salman F, Haj Younes A, Msheik A. Neck and musculoskeletal pain among dentists: A review of the literature. Cureus. 2023; 15(1):e33609. [DOI:10.7759/cureus.33609] [PMID]

- AlOtaibi F, Nayfeh FMM, Alhussein JI, Alturki NA, Alfawzan AA. Evidence based analysis on neck and low back pain among dental practitioners- A systematic review. Journal of Pharmacy & Bioallied Sciences. 2022; 14(Suppl 1):S897-902. [DOI:10.4103/jpbs.jpbs_92_22] [PMID]

- Harris ML, Sentner SM, Doucette HJ, Brillant MGS. Musculoskeletal disorders among dental hygienists in Canada. Canadian Journal of Dental Hygiene. 2020; 54(2):61-7. [PMID]

- Roozegar MA, Shafiee E, Havasian MR. [Evaluation of Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in general dentists, Ilam, 2020 (Persian)]. Daneshvar Medicine 2022; 30(6):70-7. [DOI:10.22070/daneshmed.2022.16951.1290]

- Sedaghati P, Fadaei Forghan Z, Fadaei Dehcheshmeh M. [Study of musculoskeletal disorders of the cervical spine and upper extremity in dentists: A review article (Persian)]. Journal of Research in Dental Sciences. 2022; 19(1):76-87. [DOI:10.52547/jrds.19.1.76]

- Sarwar S, Khalid S, Mahmood T, Jabeen H, Imran Sh. Frequency of neck and upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders in dentists. Journal of Islamabad Medical & Dental College. 2020; 9(3):207-11.[DOI:10.35787/jimdc.v9i3.404.]

- Kumar M, Pai KM, Vineetha R. Occupation-related musculoskeletal disorders among dental professionals. Medicine and Pharmacy Reports. 2020; 93(4):405-9. [DOI:10.15386/mpr-1581] [PMID]

- Eskandari Nasab N, Mirmohammadi SJ, Mehrparvar AH, Fallah H. [Study of effectiveness and reliability of education on ergonomic risk factors and musculoskeletal complaints in patient-carrier personnel of Shahid Bahonar hospital of Kerman (Persian)]. Occupational Medicine. 2019; 10(4):23-30. [DOI:10.18502/tkj.v10i4.1732]

- Bahrami M, Sadeghi M, Dehdashti A, Karami M. [Assessment of the effectiveness of ergonomics training on the improvement of work methods among hospital office staff (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Ergonomics. 2018; 6(2):34-45. [DOI:10.30699/jergon.6.2.34]

- Abdollahi T, Pedram Razi S, Pahlevan D, Yekaninejad MS, Amaniyan S, Leibold Sieloff C, et al. Effect of an ergonomics educational program on musculoskeletal disorders in nursing staff working in the operating room: A quasi-randomized controlled clinical trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(19):7333. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17197333]

- Yao Y, Zhao S, An Z, Wang S, Li H, Lu L, et al. The associations of work style and physical exercise with the risk of work-related musculoskeletal disorders in nurses. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health. 2019; 32(1):15-24. [DOI:10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01331] [PMID]

- Cento AS, Leigheb M, Caretti G, Penna F. Exercise and exercise mimetics for the treatment of musculoskeletal disorders. Current Osteoporosis Reports. 2022; 20(5):249-59. [DOI:10.1007/s11914-022-00739-6] [PMID]

- Soroush S, Arefi MF, Pouya AB, Barzanouni S, Heidaranlu E, Gholizadeh H, et al. The effects of neck, core, and combined stabilization practices on pain, disability, and improvement of the neck range of motion in elderly with chronic non-specific neck pain. Work. 2022; 71(4):889-900. [DOI:10.3233/WOR-213646] [PMID]

- Azadi F, Amjad RN, Marioryad H, Alimohammadi M, Karimpour Vazifehkhorani A, Poursadeghiyan M. [Effect of 12-week neck, core, and combined stabilization exercises on the pain and disability of elderly patients with chronic non-specific neck pain: A clinical trial (Persian)]. Salmand: Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2019; 13(5):614-25. [DOI:10.32598/SIJA.13.Special-Issue.614]

- Sarraf F, Safari Variani A, Varmazyar S. [The relationship between demographic information and bag weight with neck disability index, angles and head and neck postures among college students (Persian)]. Journal of Health and Safety at Work. 2022; 12(2):352-66. [Link]

- Javdaneh N, Letafat Kar A, Kamrani Faraz N. [Comparison of Physical therapy with and without positional release technique on the pain, disability and range of motion in chronic low back pain patients (Persian)]. Journal of Anesthesiology and Pain. 2018; 9(1):74-86. [Link]

- Tariq F, Kashif M, Mehmood,A, Quraishi A. Prevalence of neck pain and its effects on activities of daily living among dentists working in Faisalabad. Rehman Journal of Health Sciences. 2020; 2(1):10-13. [DOI:10.52442/rjhs.v2i1.28.]

- Ajwa N, Khunaizi FA, Orayyidh AA, Al Qattan W, Bujbarah F, Bukhames G, et al. Neck and back pain as reported by dental practitioners in Riyadh City. Journal of Dental Health Oral Disorders & Therapy. 2018; 9(4):340-5. [DOI:10.15406/jdhodt.2018.09.00405]

- Holmström E, Engholm G. Musculoskeletal disorders in relation to age and occupation in Swedish construction workers. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2003; 44(4):377-84. [DOI:10.1002/ajim.10281] [PMID]

- Ahmadi Motemayel F, Abdolsamadi H, Roshanaei G, Jalilian S. [Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among Hamadan general dental practitioners (Persian)]. Avicenna Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2012; 19(3):61-6. [Link]

- Putri BA. The correlation between age, years of service, and working postures and the complaints of musculoskeletal disorders. The Indonesian Journal of Occupational Safety and Health. 2019; 8(2):187-96. [DOI:10.20473/ijosh.v8i2.2019.187-196]

- Heidari M, Ghodusi Borujeni M, Rezaei P, Kabirian Abyaneh S. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders and their associated factors in nurses: A cross-sectional study in Iran. The Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2019; 26(2):122-130. [DOI:10.21315/mjms2019.26.2.13]

- Rokni M, Abadi MH, Saremi M, Mir Mohammadi MT. [Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in nurses and its relationship with the knowledge of ergonomic and environmental factors (Persian)]. Journal of Gorgan University of Medical Sciences. 2016; 18(1):128-32. [Link]

- Jari A, Niazmand-Aghdam N, Mazhin SA, Poursadeghiyan M, Sahlabadi AS. Effectiveness of training program in manual material handling: A health promotion approach. Journal of Education and Health Promotion. 2022; 11(1):81.[DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_492_21]

- Sowah D, Boyko R, Antle D, Miller L, Zakhary M, Straube S. Occupational interventions for the prevention of back pain: Overview of systematic reviews. Journal of Safety Research. 2018; 66:39-59. [DOI:10.1016/j.jsr.2018.05.007] [PMID]

- Ebrahimi H. [Investigation of the impact of ergonomic training programs on the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders of adminis-trative and support staff at Imam Reza Hospital in Mashhad, Iran (Persian)]. Journal of Occupational Hygiene Engineering. 2022; 9(4):222-9. [DOI:10.52547/johe.9.4.222]

- Bolghanabadi S, Khanzade F, Gholami F, Moghimi N. [Investigation of risk factors for musculoskeletal disorders by quick exposure check and effect of ergonomic intervention on reducing disorders in assemblers in an electric industry worker (Persian)]. Journal of Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences. 2020; 27(4):614-9. [Link]

- Sohrabi MS, Babamiri M. Effectiveness of an ergonomics training program on musculoskeletal disorders, job stress, quality of work-life and productivity in office workers: A quasi-randomized control trial study. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics. 2022; 28(3):1664-71. [DOI:10.1080/10803548.2021.1918930] [PMID]

- Omi Kalteh H, Hekmat Shoar R, Taban E, Faghih M, Yazdani Avval M, Shokri S. [Effects of an ergonomic training program on the reduction of musculoskeletal disorders (Persian)]. Journal of Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences. 2016; 23(1):58-65. [Link]

- Sundstrup E, Seeberg KGV, Bengtsen E, Andersen LL. A systematic review of workplace interventions to rehabilitate musculoskeletal disorders among employees with physical demanding work. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2020; 30(4):588-612. [DOI:10.1007/s10926-020-09879-x] [PMID]

- Gwinnutt JM, Wieczorek M, Cavalli G, Balanescu A, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Boonen A, et al. Effects of physical exercise and body weight on disease-specific outcomes of people with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs): Systematic reviews and meta-analyses informing the 2021 EULAR recommendations for lifestyle improvements in people with RMDs. RMD Open. 2022; 8(1):e002168. [DOI:10.1136/rmdopen-2021-002168] [PMID]

- Serra MVGB, Camargo PR, Zaia JE, Tonello MGM, Quemelo PRV. Effects of physical exercise on musculoskeletal disorders, stress and quality of life in workers. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics. 2018; 24(1):62-7. [DOI:10.1080/10803548.2016.1234132]

Article type: Original Research Articles |

Subject:

Ergonomics

Received: 2024/01/14 | Accepted: 2024/03/16 | Published: 2025/09/1

Received: 2024/01/14 | Accepted: 2024/03/16 | Published: 2025/09/1

Send email to the article author