Volume 22, Issue 1 (March 2024)

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2024, 22(1): 129-138 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Khabbache H, Ouazizi K, Ait Ali D, Cherqui A, Rizzo A, Tarchi L, et al . Cultural Placebos From the Wild in Patients With Mental Disorders: The Case of the Nour Association in Fez-Morocco. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2024; 22 (1) :129-138

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2204-en.html

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2204-en.html

Hicham Khabbache1

, Khalid Ouazizi1

, Khalid Ouazizi1

, Driss Ait Ali *1

, Driss Ait Ali *1

, Abdelhalim Cherqui1

, Abdelhalim Cherqui1

, Amelia Rizzo2

, Amelia Rizzo2

, Livio Tarchi3

, Livio Tarchi3

, Sefa Bulut4

, Sefa Bulut4

, Łukasz Szarpak5

, Łukasz Szarpak5

, Mohamed Makkaoui1

, Mohamed Makkaoui1

, Hanane El Ghouat1

, Hanane El Ghouat1

, Parisa Jalilzadeh Afshari6

, Parisa Jalilzadeh Afshari6

, Rezvaneh Namazi Yousefi7

, Rezvaneh Namazi Yousefi7

, Francesco Chirico8

, Francesco Chirico8

, Khalid Ouazizi1

, Khalid Ouazizi1

, Driss Ait Ali *1

, Driss Ait Ali *1

, Abdelhalim Cherqui1

, Abdelhalim Cherqui1

, Amelia Rizzo2

, Amelia Rizzo2

, Livio Tarchi3

, Livio Tarchi3

, Sefa Bulut4

, Sefa Bulut4

, Łukasz Szarpak5

, Łukasz Szarpak5

, Mohamed Makkaoui1

, Mohamed Makkaoui1

, Hanane El Ghouat1

, Hanane El Ghouat1

, Parisa Jalilzadeh Afshari6

, Parisa Jalilzadeh Afshari6

, Rezvaneh Namazi Yousefi7

, Rezvaneh Namazi Yousefi7

, Francesco Chirico8

, Francesco Chirico8

1- Laboratory of Morocco: History, Theology and Languages, Department of Psychology, Faculty of Arts and Human Sciences Fès-Saïss, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, Fez, Morocco.

2- Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Messina, Messina, Italy.

3- Department of Health Sciences, University of Florence, Florence, Italy.

4- Department of Counseling Psychology, Counseling Center, School of Education, Ibn Haldun University, Istanbul, Türkiye.

5- Department of Clinical Research and Development, LUXMED Group, Warsaw, Poland.

6- Department of Audiology, School of Rehabilitation, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

7- Deputy of Research and Technology, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Islamic Republic of Iran.

8- Faculty of Medicine and Surgery, Specialization School in Occupational Medicine, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Rome, Italy.

2- Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Messina, Messina, Italy.

3- Department of Health Sciences, University of Florence, Florence, Italy.

4- Department of Counseling Psychology, Counseling Center, School of Education, Ibn Haldun University, Istanbul, Türkiye.

5- Department of Clinical Research and Development, LUXMED Group, Warsaw, Poland.

6- Department of Audiology, School of Rehabilitation, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

7- Deputy of Research and Technology, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Islamic Republic of Iran.

8- Faculty of Medicine and Surgery, Specialization School in Occupational Medicine, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Rome, Italy.

Full-Text [PDF 645 kb]

(710 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2469 Views)

Full-Text: (663 Views)

Introduction

The study took place at the NOUR Association in Fez, Morocco, established by the local community to support approximately sixty patients with various mental disorders, including schizophrenia, melancholy, bipolar disorder, paranoia, hysteria, and other conditions, as diagnosed by conventional criteria. A team comprising three psychiatrists, two nurses, and one social worker from Fez’s psychiatric hospital volunteered their services to the association.

In Morocco, psycho-clinical and psychiatric services operate in a context of limited resources. For a population of around 34 million, there are only 350 psychiatrists, 60 clinical psychologists, and about 400 psychiatric social workers and nurses. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Morocco’s average employee in the field of mental health is approximately nine workers per 100,000 people [1]. This severe shortage of mental health experts escalates because they have to operate in a population of about 48.9% of citizens suffering from mental disorders. For example, deep depression affected approximately 26.5% of the general population [1, 2].

Burnout is common among mental health professionals. Consequently, only three psychiatrists were willing to volunteer at the NOUR Association. As a token of appreciation, they were elected to the association’s board by the general assembly. However, they were later dismissed due to political conflicts arising from differences between the shareholders’ pragmatic interests and the psychiatrists’ professional goals. Subsequently, the two nurses and the social worker also left the association for personal reasons, leaving the Nour Center without any professional staff.

In these unfortunate circumstances, two social work students, who were already familiar with the Nour Association from their practice placements, agreed to return and run the association. One of them collaborated in the authorship of this study. They received support from their supervisors as necessary, guided by the principle of “giving back” central to anthropology in action. This principle emphasizes a reciprocal exchange where researchers gather insights from participants’ experiences and contribute positively to the community in return [3].

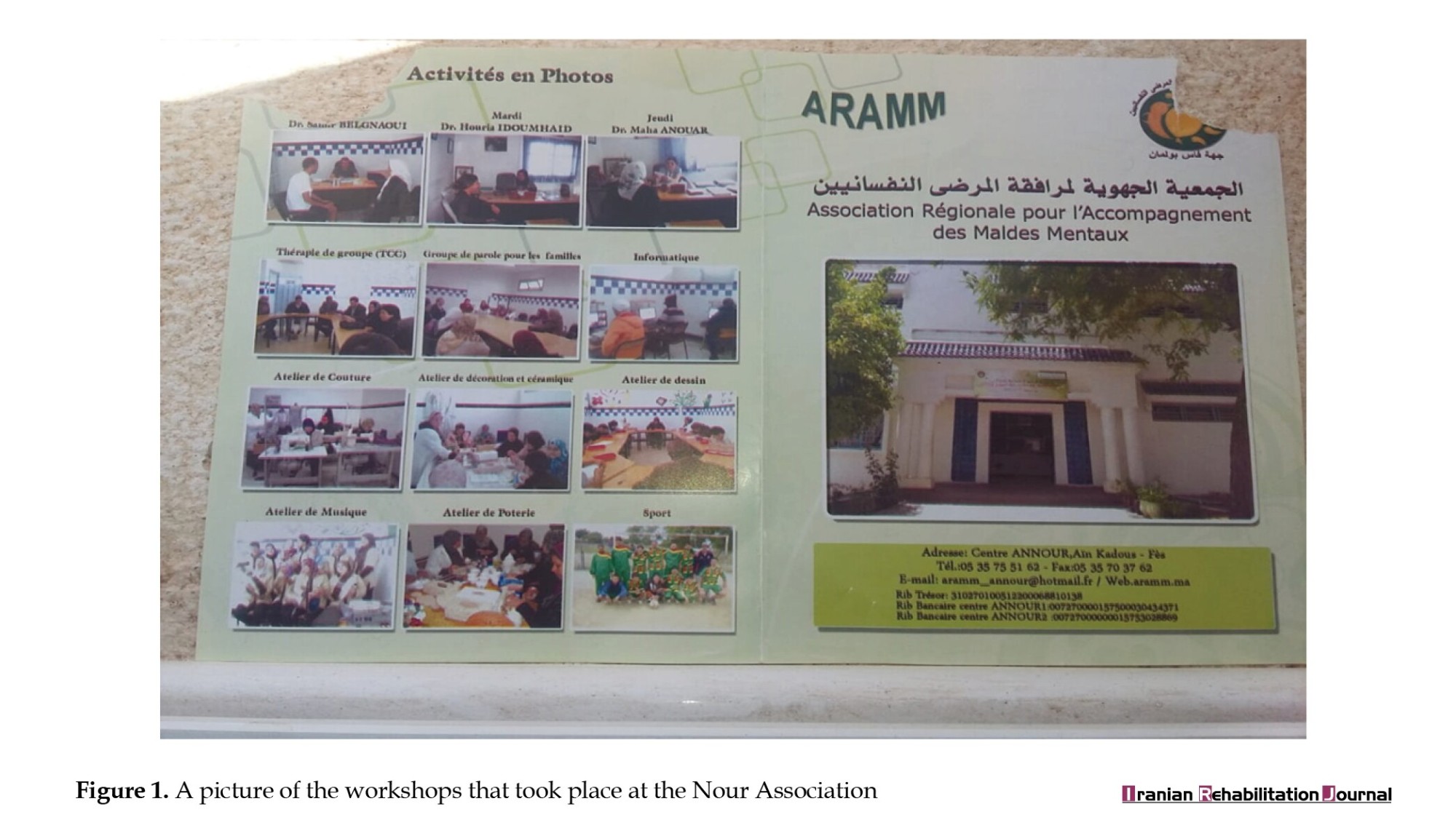

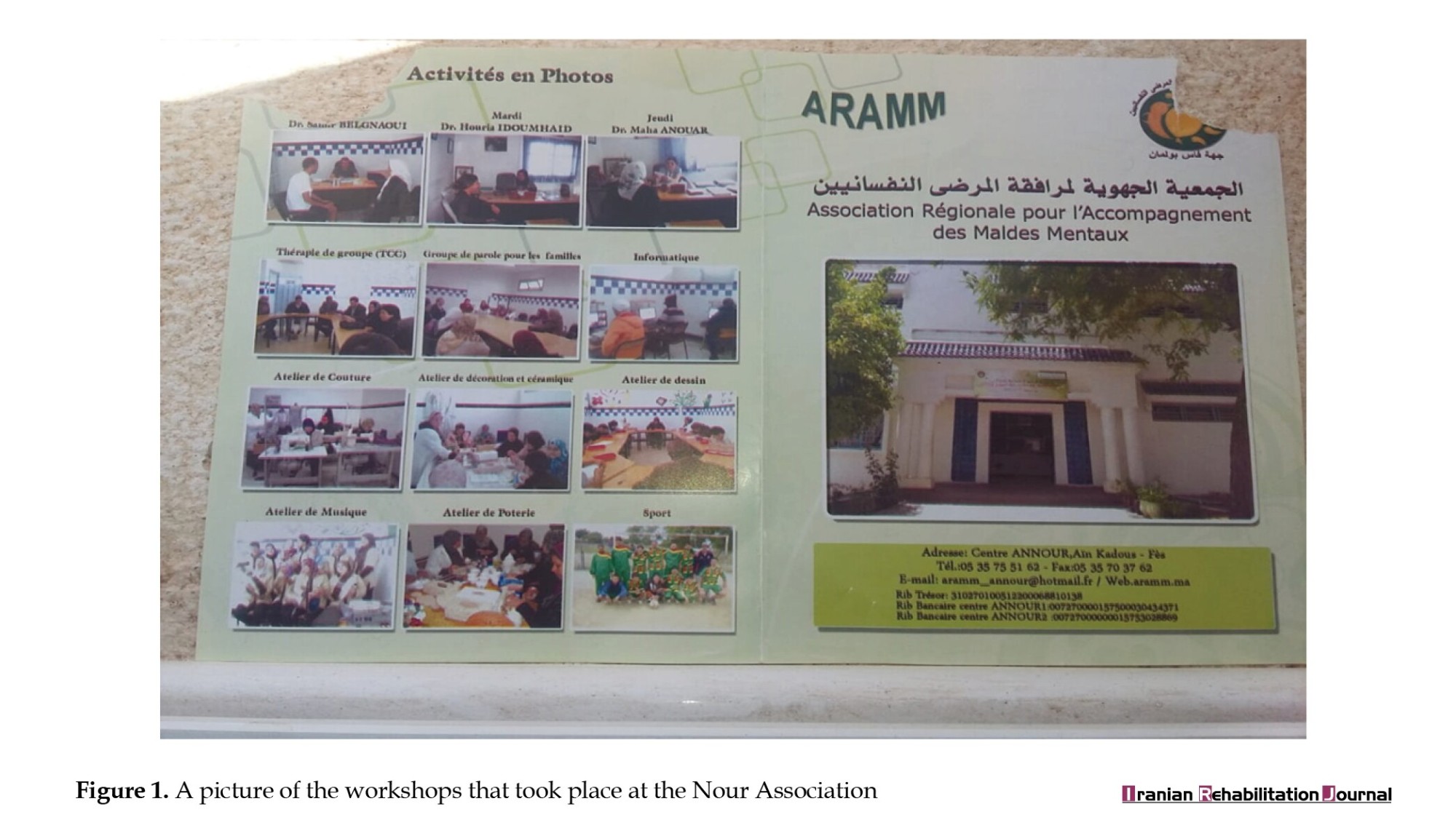

The project researchers adopted an approach based on analyzing the members’ needs, leading to the development of various collaborative workshops. These workshops encompassed therapeutic activities and practical skills development, including sewing, decoration, ceramics, drawing, music, sports, and computer training, as illustrated (Figure 1).

His study suggests that organizing activities within the Noor Association acts as a rehabilitation form, especially within its unique context. By focusing on the unique setting of the Noor Association, the research aimed to shed light on the transformative potential of these organized activities for patients. It argues that even without health professionals’ direct involvement, these activities significantly contribute to the rehabilitation of individuals with mental health issues, underscoring the importance of the specific setting in understanding rehabilitation’s complex dynamics within a community-driven framework.

Thirty patients attended the Center constantly during the eighteen-month period covered by the research study, whilst about the same number also attended on a more irregular basis. Participants ranged from 18 to 55 years old, including 12 females and 48 males. This study aims to systematically explore the phenomenon of recovery, focusing specifically on the patients’ self-initiated awakening and self-healing within a unique biocultural environment. We tried to examine how numerous patients, left without psychiatric support, navigated through their vulnerable states. In essence, we seek to understand how these individuals improved their psychological well-being without conventional hospitalization and how broader socio-cultural dynamics influence their individual psychological representations and thought processes, and vice versa. Furthermore, we are curious to explore whether medical practices, guided by the patients’ own cultural knowledge (ethnoscience), naturally developed within the Nour Center [4].

Materials and Methods

In this research, we engaged in two levels of analysis: Firstly, we chose participant observation to learn about the intricacies of the activities that took place in the Nour Center in their natural setting, on a day-to-day basis. This involved recording conversations as they naturally occurred among patients. Additionally, we collected 12 narrative reports during the 2016-2017 period; these provided a comprehensive account of events and activities that happened in the Nour Center, which could then form the basis of detailed ethnographic analysis [5].

Second, we employed three cognitive mechanisms namely, conceptual metaphor theory [6, 7], schema theory [8, 9], and frame theory [10, 11], which we believe to be adequate to describe, and hence access, the patients’ conceptual system, potentially revealing significant changes in their mental health status. Results and discussion.

In the literacy workshop: From processes to mindsets

Based on the initial interactions and the needs analysis conducted by the social workers, one of the earliest and most impactful workshops focused on teaching patients reading and writing skills. In the beginning, patients with limited literacy skills explained their clinical diagnostic status by referring to their oral traditions and lay theory, likening the symptoms they experienced to being possessed by the devil, a victim of the wicked eye, or coming under the influence of an act of witchcraft.

However, as the patients’ writing and reading skills started to improve, their discourse about their clinical diagnostic status changed significantly. They started using pseudo-scientific explanations, to which they had previously been introduced, applying technical jargon to explain their experiences: “Sometimes, I have additive or visual hallucinations,” patient AD, a 25-year-old male stated. “I suffer from psychotic disorders,” Patient ZH, a 28-year-old male stated”. Patient LB, a 29-year-old male, expressed, “I am not shy but I am afraid to speak publically, it is a kind of social phobia”.

Further, comparing the writings of literate to illiterate patients revealed that the former were more adept at articulating and understanding, with greater clarity, the mental states of others. For instance, they could detail the progress or setbacks in their mental health: “I am now well..., but two weeks ago, I was very nervous and couldn’t control myself,” shared Patient L.P., a 29-year-old male. This indicates the patient’s engagement in self-monitoring, a crucial part of the broader self-empowerment process [12, 13].

Moreover, writing allows shy or introverted patients to communicate indirect messages to their interlocutors. Therefore, writing served as a means for shy or introverted patients to convey indirect messages, creating a context free of anxiety for the writer, which eased their reluctance and encouraged more open self-expression. Additionally, writing gives the patient or writer the possibility to disguise their identity, which creates a disinhibition effect [14, 15]. Some patients who were able to express themselves fluently in writing could narrate their everyday life stories and their taboos without any resistance: “Writing gives me enough courage to say everything, …., because I feel I am like a ghost”, confessed Patient P.L., a 35-year-old male.

Similarly, writing and reading activities allow some patients to reflect on their mental and emotional states, and to understand and manage them [14, 16]: “It’s magical, I used to hate Zayed, but when I wrote that …., I felt that my hatred to him had been reduced”, shared Patient A.B, a 40-year-old male. This indicates the patient’s engagement in metacognitive processes of self-regulation.

Additionally, using writing as a means of communication permits the patients to develop their internal “private speech” [13], “When I write I feel I am speaking to myself”, said Patient MA, a 25-year-old female. Through this internal dialogue, the patient can critically examine her lay theories, attitudes, and misunderstandings regarding her clinical condition.

Conversely, reading others’ messages helps patients put their own suffering into perspective, realizing they are not alone in their struggles. “When I read a message about others’ sufferings, I feel as if they are my own,” mentioned Patient BL, a 25-year-old male. Sympathy towards others is a common reaction upon reading their messages: “When I read her messages, I felt her pain,” expressed Patient NF, a 35-year-old female. In some instances, this sympathy evolves into empathy: “I hear her voice in my head,” said Patient LL, a 45-year-old female.

However, there’s a downside to this sympathy, as seen when patients internalize the negative emotions shared by others. For example, after reading the melancholic messages of a peer, one patient began experiencing similar feelings: “Rachid is always complaining, he is gloomy. Now I feel that I am dark inside like him,” Patient K.J., a 30-year-old male, reflected.

Finally, writing stirred the patients’ courage to express their sufferings not only with their functional community “the community of the patients”, but also with the outside world. On social media (Facebook), for instance, using their nicknames, some of the patients started to speak publicly about their sufferings and problems. Also, some patients tried to put their troubles into perspective by consulting books, journals, and websites on psycho-pathology.

To summarize, the communicative skills of the patients evolved remarkably, advancing to what could be termed “a change in mindset”—shifting from articulating isolated psychic statuses (statements) to forming networks of discourse. This evolution, we hypothesize, was facilitated by the alteration in frames—the NOUR center, embodying “the home frame,” acted as a catalyst, encouraging isolated statements to interconnect into broader networks. This transformation mirrored the patients’ progression from intrapersonal to interpersonal experiences [13, 17].

In the drama workshop: From mindsets to cultural placebos

In the process of unfolding events, we noted that a sort of “informal drama workshop” was developed among patients. It took the form of a social ritual due to its repetitive practice. Some patients, especially those who knew some notions about psychology and psychiatry were solicited by other patients to play the role of psychiatrists, and those who were less educated accepted to play the role of the patient. Thus, the patients who played the role of the psychiatrist interrogated and wrote a medical prescription and those who played the role of patients listened attentively and answered questions. This role-play appeared to confer multiple benefits:

a) The patient who played the role of the psychiatrist started to develop self-esteem by imitating and identifying with the psychiatrist’s status, which is another step towards attaining self-empowerment “When I play the role of a doctor, I feel I am a much-respected man”, shared H.L, a 35-year-old male.

b) Patients acting in the patient role were notably keen to elaborate on their mental and emotional states in great detail to those playing doctors, likely due to a sense of empathy stronger than what is typically experienced with actual doctors. “Ali is my real doctor, even if he is sick like me… A Moroccan proverb says: Seek the opinion of the experiencer, not the doctor,” remarked Patient KL, a 40-year-old male. This interaction appears to foster self-description and self-explanation, which, in turn, promotes self-empowerment and hints at the emergence of peer therapy facilitated by patient experts.

c) On a more abstract level, the drama workshop evoked “the hospital frame”, which could be conceptually reconstructed as follows:

1. The Nour Center itself serves as the hospital.

2. The doctors are the patients’ tutors.

3. The patients are the patients’ tutees.

4. The prescription is represented by the fake prescription given by the patient’s tutor.

Accordingly, the hospital frame elicited various schemas, the most notable being the FUNCTION schema. To vividly illustrate how this schema was activated by a patient-tutor with a patient-tutee who believed he was possessed by the devil, consider this verbatim exchange:

A: “Do you get confused when you read the Quran?”

B: The patient replied: “No”

A: “Do you get the desire to vomit when you eat meat?”

B: The patient replied “No”

A: “Do you constantly have nosebleeds?”

B: The patient replied “No”

A: “Does your body smell bad, and other people don’t?”

B: The patient replied “No”

A: “Does your hair grow fast?”

B: The patient replied “No, I am bald”

A: “Do your nails grow fast?”

B: The patient replied “No”

A: “That means you’re not possessed by a devil, you are only mentally ill”.

This dialogue is noteworthy for the tutor’s approach to addressing the tutee’s lay theory; he engaged in a nuanced dialogue by appearing to accept the patient’s beliefs. This interaction led to what psychologists refer to as “cognitive dissonance” for the tutee, stemming from conflicting beliefs about being mentally ill and/or possessed by a devil. Initially, the tutor employed the same explanatory schemas and frames as the tutee to establish trust before refuting his lay theories decisively.

Accordingly, the drama workshop is perhaps a substantial epitome of what we have called a “cultural placebo”, underlined by the FUNCTION schema, which can be deconstructed as follows:

1. An input, the cultural placebo, represented by the simulated therapeutic session or “diagnostic test” conducted by the patient-tutor, aimed to evoke both a humorous and therapeutic effect, embodying the notion that “the human being who acts is the human being who lives” [11].

2. The relationship, fosters belief in the healing power of the patient-tutor (Y) through the therapy session (Z) from the patient-tutee (X). Cognitively, it was mediated by the “iconoclasm of the patient”, i.e. the refutation of the patient’s fallacious beliefs about his health status.

3. An output, the placebo effect, in this context, is the patient’s awakening—induced by his iconoclasm—prompting a conceptual and neurological reevaluation of his mental health status, transitioning from believing in demonic possession to recognizing his normality.

In the beginning, it is worth noticing that the FUNCTION schema underlying the above “therapeutic session” might be interpreted as a “cultural placebo” only as far the ‘diagnostic test’ is not valid from a genuinely psychiatric (professional) perspective. A placebo is, by definition, a non-effective (fake) treatment.

Specifically, one patient explaining another’s ‘case’ initiates a “metaphorical mapping” process between their own mental states and those of another [19, 20]. This metaphorical mapping involves two sub-processes: The first is evident when a patient tries to draw parallels between herself and another, termed ‘the identification phase.’ Here, the patient starts to believe that they share the same clinical condition [19–22].

The ‘projection phase’ begins when the patient extends her state onto another’s self. This projection can lead to empathy, where a patient describes another’s mental and affective states as though they were her own experiences. “Your sufferings were similar to what I felt in the past, I went through them three months ago and managed to overcome them,” says patient L.M, female, aged 36 years old. It is presumed that similar psychological processing occurs between the patient-tutor and the patient-tutee.

Ultimately, the deployment of metaphorical mapping activated the presence of “awakening” processes, enabling the patient to gain insight and control over their mental and emotional states. Among the unequivocal signs of the existence of awakening was the patient’s ability to take a critical look at his own and others’ illusions and hallucinations: “It’s not reality, it’s only a hallucination”, states patient HK, a male, aged 37 years old (the patient-tutee), marking a significant step in his healing by achieving self-relief.

The qualitative data suggests an ad hoc “theory-free” model of therapy, encouraging self-initiation and self-directed healing. This model is theory-free, relying solely on the informal and emic aspects, i.e. the model is the result of the patients’ pure reasoning and feedback to others’ reasoning, without resorting to any formal theory of any kind. We will try to demonstrate the legitimacy of this approach in the next sections.

The departure of psychiatrists from the center and the shift towards local culture led to the creation of a holistic health education program, characterized by natural principles of dynamic complex socio-cultural systems such as self-regulation. Peer therapy activated self-healing among patients without dependence on any “executive function system,” like a psychiatrist or psychologist, purely through collective intelligence fostered by a range of interpersonal and intrapersonal interactions, further discussed in the next section [22].

To begin, the psychological awakening of the patients might be described in multiple ways: First, through representations and processes, manifested as: a) Frames, b) Schemas, and c) Conceptual metaphors; Second, in relation to the evolution of patients’ medical understanding: (i) mythical phase, marking the initial state of the patients upon joining the center, where they leaned on their lay theories to interpret their and their peers’ psychic conditions (ii) pseudo-scientific phase, marked by patients using sophisticated schemas and conceptual metaphors—evident in self-description and self-regulation—that facilitated some degree of self-healing and relief; and (iii) scientific phase, distinguished by a breakthrough in the application and execution of cultural placebos.

Cultural placebos have stood the test of time, having been in existence for many years, remaining present today, and, it is presumed, will continue into the future. We believe that cultural placebos, which are symbolically unified by the underlay function schema, are powerful medical instruments across different evolutionary stages.

The pedagogical harvest of this study is that “theory-neutral” therapy deploys various forms of learning: a) Constructive learning [23, 24], where the patient is an active entity capable of achieving mental optimization independently or with peer assistance; b) Autonomous learning, with the patient self-planning, self-managing, and self-evaluating her health to effect recovery and awakening; c) Peer-supported learning, as patients educate each other [25].

Consequently, cultural placebos center on the patient, recognizing specific profiles while acknowledging the presence of shared traits among group predispositions. We believe that the application of cultural placebos varies due to: (i) cultural differences across cultures; (ii) interpersonal differences from one individual to another; (iii) intrapersonal differences across intellectual levels at various ages, (iv) situational differences based on each context [26].

Thus, conducting activities within an association without the direct involvement of health professionals can be viewed as a form of rehabilitation for individuals seeking recovery. Participating in structured, supportive community activities promotes a sense of inclusion and purpose, significantly enhancing the well-being of individuals with mental health issues. Initiatives led outside professional realms offer opportunities for social engagement, skill enhancement, and personal growth [27-29].

Conclusion

In summary, this study underscores that people’s health, particularly mental health, is a product of societal influences, and cultural therapy emerges from the dynamic complexities of sub-cultural systems. The patient’s psychic system requires recognizing its complexity, contextuality, and variability. The patient should be viewed as an individual with autonomous and dynamic systems that can enrich and augment traditional treatment approaches.

The Nour Association’s experiences revealed that mental health is deeply embedded in and nurtured by culture. Surprisingly, when we delve deep into the phenomenon, we uncover that both the biomedical and wild theory-neutral models have the same underlying principles that are rooted in and mediated by the same psychological and cognitive representations and processes, such as schemas, like the cultural placebo, frames, like the HOSPITAL and the family frames, and conceptual metaphors, like the metaphor of emotions are air balloons.

Accordingly, these psychological cognitive mediators above allow the patient to develop his/her self-function system of awakening by rewiring his/her old neurological network configurations and substituting them with new ones that assist his/her in managing his/her stress and monitoring his/her mental and emotional states. It can be developed in ways that are culturally specific and sensitive, and it can represent a challenge to the over-medicalization problems that are more properly understood as emerging from social systems and social dissonance. Achieving this level of awakening primarily involves leveraging the experiences and insights of peers to challenge misrepresentations, and to understand and assess the workings of their psychic system.

- On a more theoretical level, the improvised, theory-neutral program developed through interacting dynamic complex systems exhibits unique features:

- It is pedagogically founded because various learning/teaching methods were applied implicitly. The primary aim is to enable patients to draw upon their inherent resources—whether cognitive (such as schemas, frames, and metaphors), social (like peer support therapy), or cultural (including cultural placebos)—instead of relying on external sources like medication, psychiatrists, or doctors. In other words, the program pleas for what is known in the literature as “patient engagement”.

- It emerges naturally, without the need for an “executive function system” like a psychiatrist. The awakening program at the Nour Association emerged spontaneously, grounded only in socio-cultural norms. While there is no predefined formula for replicating the Nour Center’s conditions elsewhere, the key lies in creating the right environment for patients to facilitate their own mental health improvement. This involves selecting suitable activities to activate frames, which in turn proliferate schemas, and using schemas to implement and apply conceptual metaphor mappings and cultural placebos.

- Recovery is not confined to simply being symptom-free or a reduction in symptoms. It also encompasses a subjective experience that can manifest as “awakening.”. Boldly stated, there are no mental illnesses, but rather “cultural realities”; meaning, illness, and recovery are concepts open to cultural negotiation.

Limitations

Two main limitations are worth mentioning. Firstly, our analysis has not been formulated into a formal model with clear theses and hypotheses, leading to the second limitation. Consequently, our analysis does not meet the criterion of replicability.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study obtained ethical approval from the Institutional Ethics Review Board of the Department of Applied Psychology, Faculty of Arts and Human Sciences Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University (Code: 05/15). This research was conducted with utmost commitment to ethical considerations, ensuring the voluntary collaboration of participants, upholding patients’ right to self-determination, and rigorously adhering to ethical guidelines regarding privacy, anonymity, and data confidentiality

Funding

This research was funded by “Le Centre National de Recherche Scientifique et Technique, Maroc: Cov/2020/28)” and by the “Lifelong Learning Observatory (UNESCO).

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their sincere gratitude to all the volunteers who participated in the activities with the Noor Association.

References

The study took place at the NOUR Association in Fez, Morocco, established by the local community to support approximately sixty patients with various mental disorders, including schizophrenia, melancholy, bipolar disorder, paranoia, hysteria, and other conditions, as diagnosed by conventional criteria. A team comprising three psychiatrists, two nurses, and one social worker from Fez’s psychiatric hospital volunteered their services to the association.

In Morocco, psycho-clinical and psychiatric services operate in a context of limited resources. For a population of around 34 million, there are only 350 psychiatrists, 60 clinical psychologists, and about 400 psychiatric social workers and nurses. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Morocco’s average employee in the field of mental health is approximately nine workers per 100,000 people [1]. This severe shortage of mental health experts escalates because they have to operate in a population of about 48.9% of citizens suffering from mental disorders. For example, deep depression affected approximately 26.5% of the general population [1, 2].

Burnout is common among mental health professionals. Consequently, only three psychiatrists were willing to volunteer at the NOUR Association. As a token of appreciation, they were elected to the association’s board by the general assembly. However, they were later dismissed due to political conflicts arising from differences between the shareholders’ pragmatic interests and the psychiatrists’ professional goals. Subsequently, the two nurses and the social worker also left the association for personal reasons, leaving the Nour Center without any professional staff.

In these unfortunate circumstances, two social work students, who were already familiar with the Nour Association from their practice placements, agreed to return and run the association. One of them collaborated in the authorship of this study. They received support from their supervisors as necessary, guided by the principle of “giving back” central to anthropology in action. This principle emphasizes a reciprocal exchange where researchers gather insights from participants’ experiences and contribute positively to the community in return [3].

The project researchers adopted an approach based on analyzing the members’ needs, leading to the development of various collaborative workshops. These workshops encompassed therapeutic activities and practical skills development, including sewing, decoration, ceramics, drawing, music, sports, and computer training, as illustrated (Figure 1).

His study suggests that organizing activities within the Noor Association acts as a rehabilitation form, especially within its unique context. By focusing on the unique setting of the Noor Association, the research aimed to shed light on the transformative potential of these organized activities for patients. It argues that even without health professionals’ direct involvement, these activities significantly contribute to the rehabilitation of individuals with mental health issues, underscoring the importance of the specific setting in understanding rehabilitation’s complex dynamics within a community-driven framework.

Thirty patients attended the Center constantly during the eighteen-month period covered by the research study, whilst about the same number also attended on a more irregular basis. Participants ranged from 18 to 55 years old, including 12 females and 48 males. This study aims to systematically explore the phenomenon of recovery, focusing specifically on the patients’ self-initiated awakening and self-healing within a unique biocultural environment. We tried to examine how numerous patients, left without psychiatric support, navigated through their vulnerable states. In essence, we seek to understand how these individuals improved their psychological well-being without conventional hospitalization and how broader socio-cultural dynamics influence their individual psychological representations and thought processes, and vice versa. Furthermore, we are curious to explore whether medical practices, guided by the patients’ own cultural knowledge (ethnoscience), naturally developed within the Nour Center [4].

Materials and Methods

In this research, we engaged in two levels of analysis: Firstly, we chose participant observation to learn about the intricacies of the activities that took place in the Nour Center in their natural setting, on a day-to-day basis. This involved recording conversations as they naturally occurred among patients. Additionally, we collected 12 narrative reports during the 2016-2017 period; these provided a comprehensive account of events and activities that happened in the Nour Center, which could then form the basis of detailed ethnographic analysis [5].

Second, we employed three cognitive mechanisms namely, conceptual metaphor theory [6, 7], schema theory [8, 9], and frame theory [10, 11], which we believe to be adequate to describe, and hence access, the patients’ conceptual system, potentially revealing significant changes in their mental health status. Results and discussion.

In the literacy workshop: From processes to mindsets

Based on the initial interactions and the needs analysis conducted by the social workers, one of the earliest and most impactful workshops focused on teaching patients reading and writing skills. In the beginning, patients with limited literacy skills explained their clinical diagnostic status by referring to their oral traditions and lay theory, likening the symptoms they experienced to being possessed by the devil, a victim of the wicked eye, or coming under the influence of an act of witchcraft.

However, as the patients’ writing and reading skills started to improve, their discourse about their clinical diagnostic status changed significantly. They started using pseudo-scientific explanations, to which they had previously been introduced, applying technical jargon to explain their experiences: “Sometimes, I have additive or visual hallucinations,” patient AD, a 25-year-old male stated. “I suffer from psychotic disorders,” Patient ZH, a 28-year-old male stated”. Patient LB, a 29-year-old male, expressed, “I am not shy but I am afraid to speak publically, it is a kind of social phobia”.

Further, comparing the writings of literate to illiterate patients revealed that the former were more adept at articulating and understanding, with greater clarity, the mental states of others. For instance, they could detail the progress or setbacks in their mental health: “I am now well..., but two weeks ago, I was very nervous and couldn’t control myself,” shared Patient L.P., a 29-year-old male. This indicates the patient’s engagement in self-monitoring, a crucial part of the broader self-empowerment process [12, 13].

Moreover, writing allows shy or introverted patients to communicate indirect messages to their interlocutors. Therefore, writing served as a means for shy or introverted patients to convey indirect messages, creating a context free of anxiety for the writer, which eased their reluctance and encouraged more open self-expression. Additionally, writing gives the patient or writer the possibility to disguise their identity, which creates a disinhibition effect [14, 15]. Some patients who were able to express themselves fluently in writing could narrate their everyday life stories and their taboos without any resistance: “Writing gives me enough courage to say everything, …., because I feel I am like a ghost”, confessed Patient P.L., a 35-year-old male.

Similarly, writing and reading activities allow some patients to reflect on their mental and emotional states, and to understand and manage them [14, 16]: “It’s magical, I used to hate Zayed, but when I wrote that …., I felt that my hatred to him had been reduced”, shared Patient A.B, a 40-year-old male. This indicates the patient’s engagement in metacognitive processes of self-regulation.

Additionally, using writing as a means of communication permits the patients to develop their internal “private speech” [13], “When I write I feel I am speaking to myself”, said Patient MA, a 25-year-old female. Through this internal dialogue, the patient can critically examine her lay theories, attitudes, and misunderstandings regarding her clinical condition.

Conversely, reading others’ messages helps patients put their own suffering into perspective, realizing they are not alone in their struggles. “When I read a message about others’ sufferings, I feel as if they are my own,” mentioned Patient BL, a 25-year-old male. Sympathy towards others is a common reaction upon reading their messages: “When I read her messages, I felt her pain,” expressed Patient NF, a 35-year-old female. In some instances, this sympathy evolves into empathy: “I hear her voice in my head,” said Patient LL, a 45-year-old female.

However, there’s a downside to this sympathy, as seen when patients internalize the negative emotions shared by others. For example, after reading the melancholic messages of a peer, one patient began experiencing similar feelings: “Rachid is always complaining, he is gloomy. Now I feel that I am dark inside like him,” Patient K.J., a 30-year-old male, reflected.

Finally, writing stirred the patients’ courage to express their sufferings not only with their functional community “the community of the patients”, but also with the outside world. On social media (Facebook), for instance, using their nicknames, some of the patients started to speak publicly about their sufferings and problems. Also, some patients tried to put their troubles into perspective by consulting books, journals, and websites on psycho-pathology.

To summarize, the communicative skills of the patients evolved remarkably, advancing to what could be termed “a change in mindset”—shifting from articulating isolated psychic statuses (statements) to forming networks of discourse. This evolution, we hypothesize, was facilitated by the alteration in frames—the NOUR center, embodying “the home frame,” acted as a catalyst, encouraging isolated statements to interconnect into broader networks. This transformation mirrored the patients’ progression from intrapersonal to interpersonal experiences [13, 17].

In the drama workshop: From mindsets to cultural placebos

In the process of unfolding events, we noted that a sort of “informal drama workshop” was developed among patients. It took the form of a social ritual due to its repetitive practice. Some patients, especially those who knew some notions about psychology and psychiatry were solicited by other patients to play the role of psychiatrists, and those who were less educated accepted to play the role of the patient. Thus, the patients who played the role of the psychiatrist interrogated and wrote a medical prescription and those who played the role of patients listened attentively and answered questions. This role-play appeared to confer multiple benefits:

a) The patient who played the role of the psychiatrist started to develop self-esteem by imitating and identifying with the psychiatrist’s status, which is another step towards attaining self-empowerment “When I play the role of a doctor, I feel I am a much-respected man”, shared H.L, a 35-year-old male.

b) Patients acting in the patient role were notably keen to elaborate on their mental and emotional states in great detail to those playing doctors, likely due to a sense of empathy stronger than what is typically experienced with actual doctors. “Ali is my real doctor, even if he is sick like me… A Moroccan proverb says: Seek the opinion of the experiencer, not the doctor,” remarked Patient KL, a 40-year-old male. This interaction appears to foster self-description and self-explanation, which, in turn, promotes self-empowerment and hints at the emergence of peer therapy facilitated by patient experts.

c) On a more abstract level, the drama workshop evoked “the hospital frame”, which could be conceptually reconstructed as follows:

1. The Nour Center itself serves as the hospital.

2. The doctors are the patients’ tutors.

3. The patients are the patients’ tutees.

4. The prescription is represented by the fake prescription given by the patient’s tutor.

Accordingly, the hospital frame elicited various schemas, the most notable being the FUNCTION schema. To vividly illustrate how this schema was activated by a patient-tutor with a patient-tutee who believed he was possessed by the devil, consider this verbatim exchange:

A: “Do you get confused when you read the Quran?”

B: The patient replied: “No”

A: “Do you get the desire to vomit when you eat meat?”

B: The patient replied “No”

A: “Do you constantly have nosebleeds?”

B: The patient replied “No”

A: “Does your body smell bad, and other people don’t?”

B: The patient replied “No”

A: “Does your hair grow fast?”

B: The patient replied “No, I am bald”

A: “Do your nails grow fast?”

B: The patient replied “No”

A: “That means you’re not possessed by a devil, you are only mentally ill”.

This dialogue is noteworthy for the tutor’s approach to addressing the tutee’s lay theory; he engaged in a nuanced dialogue by appearing to accept the patient’s beliefs. This interaction led to what psychologists refer to as “cognitive dissonance” for the tutee, stemming from conflicting beliefs about being mentally ill and/or possessed by a devil. Initially, the tutor employed the same explanatory schemas and frames as the tutee to establish trust before refuting his lay theories decisively.

Accordingly, the drama workshop is perhaps a substantial epitome of what we have called a “cultural placebo”, underlined by the FUNCTION schema, which can be deconstructed as follows:

1. An input, the cultural placebo, represented by the simulated therapeutic session or “diagnostic test” conducted by the patient-tutor, aimed to evoke both a humorous and therapeutic effect, embodying the notion that “the human being who acts is the human being who lives” [11].

2. The relationship, fosters belief in the healing power of the patient-tutor (Y) through the therapy session (Z) from the patient-tutee (X). Cognitively, it was mediated by the “iconoclasm of the patient”, i.e. the refutation of the patient’s fallacious beliefs about his health status.

3. An output, the placebo effect, in this context, is the patient’s awakening—induced by his iconoclasm—prompting a conceptual and neurological reevaluation of his mental health status, transitioning from believing in demonic possession to recognizing his normality.

In the beginning, it is worth noticing that the FUNCTION schema underlying the above “therapeutic session” might be interpreted as a “cultural placebo” only as far the ‘diagnostic test’ is not valid from a genuinely psychiatric (professional) perspective. A placebo is, by definition, a non-effective (fake) treatment.

Specifically, one patient explaining another’s ‘case’ initiates a “metaphorical mapping” process between their own mental states and those of another [19, 20]. This metaphorical mapping involves two sub-processes: The first is evident when a patient tries to draw parallels between herself and another, termed ‘the identification phase.’ Here, the patient starts to believe that they share the same clinical condition [19–22].

The ‘projection phase’ begins when the patient extends her state onto another’s self. This projection can lead to empathy, where a patient describes another’s mental and affective states as though they were her own experiences. “Your sufferings were similar to what I felt in the past, I went through them three months ago and managed to overcome them,” says patient L.M, female, aged 36 years old. It is presumed that similar psychological processing occurs between the patient-tutor and the patient-tutee.

Ultimately, the deployment of metaphorical mapping activated the presence of “awakening” processes, enabling the patient to gain insight and control over their mental and emotional states. Among the unequivocal signs of the existence of awakening was the patient’s ability to take a critical look at his own and others’ illusions and hallucinations: “It’s not reality, it’s only a hallucination”, states patient HK, a male, aged 37 years old (the patient-tutee), marking a significant step in his healing by achieving self-relief.

The qualitative data suggests an ad hoc “theory-free” model of therapy, encouraging self-initiation and self-directed healing. This model is theory-free, relying solely on the informal and emic aspects, i.e. the model is the result of the patients’ pure reasoning and feedback to others’ reasoning, without resorting to any formal theory of any kind. We will try to demonstrate the legitimacy of this approach in the next sections.

The departure of psychiatrists from the center and the shift towards local culture led to the creation of a holistic health education program, characterized by natural principles of dynamic complex socio-cultural systems such as self-regulation. Peer therapy activated self-healing among patients without dependence on any “executive function system,” like a psychiatrist or psychologist, purely through collective intelligence fostered by a range of interpersonal and intrapersonal interactions, further discussed in the next section [22].

To begin, the psychological awakening of the patients might be described in multiple ways: First, through representations and processes, manifested as: a) Frames, b) Schemas, and c) Conceptual metaphors; Second, in relation to the evolution of patients’ medical understanding: (i) mythical phase, marking the initial state of the patients upon joining the center, where they leaned on their lay theories to interpret their and their peers’ psychic conditions (ii) pseudo-scientific phase, marked by patients using sophisticated schemas and conceptual metaphors—evident in self-description and self-regulation—that facilitated some degree of self-healing and relief; and (iii) scientific phase, distinguished by a breakthrough in the application and execution of cultural placebos.

Cultural placebos have stood the test of time, having been in existence for many years, remaining present today, and, it is presumed, will continue into the future. We believe that cultural placebos, which are symbolically unified by the underlay function schema, are powerful medical instruments across different evolutionary stages.

The pedagogical harvest of this study is that “theory-neutral” therapy deploys various forms of learning: a) Constructive learning [23, 24], where the patient is an active entity capable of achieving mental optimization independently or with peer assistance; b) Autonomous learning, with the patient self-planning, self-managing, and self-evaluating her health to effect recovery and awakening; c) Peer-supported learning, as patients educate each other [25].

Consequently, cultural placebos center on the patient, recognizing specific profiles while acknowledging the presence of shared traits among group predispositions. We believe that the application of cultural placebos varies due to: (i) cultural differences across cultures; (ii) interpersonal differences from one individual to another; (iii) intrapersonal differences across intellectual levels at various ages, (iv) situational differences based on each context [26].

Thus, conducting activities within an association without the direct involvement of health professionals can be viewed as a form of rehabilitation for individuals seeking recovery. Participating in structured, supportive community activities promotes a sense of inclusion and purpose, significantly enhancing the well-being of individuals with mental health issues. Initiatives led outside professional realms offer opportunities for social engagement, skill enhancement, and personal growth [27-29].

Conclusion

In summary, this study underscores that people’s health, particularly mental health, is a product of societal influences, and cultural therapy emerges from the dynamic complexities of sub-cultural systems. The patient’s psychic system requires recognizing its complexity, contextuality, and variability. The patient should be viewed as an individual with autonomous and dynamic systems that can enrich and augment traditional treatment approaches.

The Nour Association’s experiences revealed that mental health is deeply embedded in and nurtured by culture. Surprisingly, when we delve deep into the phenomenon, we uncover that both the biomedical and wild theory-neutral models have the same underlying principles that are rooted in and mediated by the same psychological and cognitive representations and processes, such as schemas, like the cultural placebo, frames, like the HOSPITAL and the family frames, and conceptual metaphors, like the metaphor of emotions are air balloons.

Accordingly, these psychological cognitive mediators above allow the patient to develop his/her self-function system of awakening by rewiring his/her old neurological network configurations and substituting them with new ones that assist his/her in managing his/her stress and monitoring his/her mental and emotional states. It can be developed in ways that are culturally specific and sensitive, and it can represent a challenge to the over-medicalization problems that are more properly understood as emerging from social systems and social dissonance. Achieving this level of awakening primarily involves leveraging the experiences and insights of peers to challenge misrepresentations, and to understand and assess the workings of their psychic system.

- On a more theoretical level, the improvised, theory-neutral program developed through interacting dynamic complex systems exhibits unique features:

- It is pedagogically founded because various learning/teaching methods were applied implicitly. The primary aim is to enable patients to draw upon their inherent resources—whether cognitive (such as schemas, frames, and metaphors), social (like peer support therapy), or cultural (including cultural placebos)—instead of relying on external sources like medication, psychiatrists, or doctors. In other words, the program pleas for what is known in the literature as “patient engagement”.

- It emerges naturally, without the need for an “executive function system” like a psychiatrist. The awakening program at the Nour Association emerged spontaneously, grounded only in socio-cultural norms. While there is no predefined formula for replicating the Nour Center’s conditions elsewhere, the key lies in creating the right environment for patients to facilitate their own mental health improvement. This involves selecting suitable activities to activate frames, which in turn proliferate schemas, and using schemas to implement and apply conceptual metaphor mappings and cultural placebos.

- Recovery is not confined to simply being symptom-free or a reduction in symptoms. It also encompasses a subjective experience that can manifest as “awakening.”. Boldly stated, there are no mental illnesses, but rather “cultural realities”; meaning, illness, and recovery are concepts open to cultural negotiation.

Limitations

Two main limitations are worth mentioning. Firstly, our analysis has not been formulated into a formal model with clear theses and hypotheses, leading to the second limitation. Consequently, our analysis does not meet the criterion of replicability.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study obtained ethical approval from the Institutional Ethics Review Board of the Department of Applied Psychology, Faculty of Arts and Human Sciences Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University (Code: 05/15). This research was conducted with utmost commitment to ethical considerations, ensuring the voluntary collaboration of participants, upholding patients’ right to self-determination, and rigorously adhering to ethical guidelines regarding privacy, anonymity, and data confidentiality

Funding

This research was funded by “Le Centre National de Recherche Scientifique et Technique, Maroc: Cov/2020/28)” and by the “Lifelong Learning Observatory (UNESCO).

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their sincere gratitude to all the volunteers who participated in the activities with the Noor Association.

References

- Kasmi A, Touri B, Khennou K, Baba H, Bouzoubaa H. Comparative Study of the Forms of Care Centers for Individuals in the Four Continents with Those in Morocco. Journal of Hunan University Natural Sciences. 2023; 50(1):89-100. [DOI:10.55463/issn.1674-2974.50.1.10]

- Khabbache H, Jebbar A, Rania N, Doucet MC, Watfa AA, Candau J, et al. Empowering patients of a mental rehabilitation center in a low-resource context: A Moroccan experience as a case study. Psychology Research and Behavior Management. 2017; 10:103-8. [DOI:10.2147/PRBM.S117456] [PMID]

- Ambomo SM. Caring for the sick person through a gift: A socio-anthropological analysis. American Journal of Nursing and Health Sciences. 2023;4(1):12-18. [DOI: 10.11648/j.ajnhs.20230401.13]

- Khabbache H, Ouazizi K, Bragazzi NL, Watfa AA, Mrabet R. Cognitive development: Towards a pluralistic and coalitional model. Cosmos and History: The Journal of Natural and Social Philosophy. 2020; 16(2):245-65. [Link]

- Dahm MR, Raine SE, Slade D, Chien LJ, Kennard A, Walters G, et al. Older patients and dialysis shared decision-making. Insights from an ethnographic discourse analysis of interviews and clinical interactions. Patient Education and Counseling. 2024; 122:108124. [DOI:10.1016/j.pec.2023.108124] [PMID]

- Thorne JP. George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Metaphors we live by. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1980. Pp. xiii + 242. - Dwight Bolinger, Language the loaded weapon: The use & abuse of language today. London and New York: Longman, 1980. Pp. ix + 214. Journal of Linguistics. 1983; 19(1):245-8. [DOI:10.1017/S002222670000760X]

- Semino E, Demjén Z. The Routledge handbook of metaphor and language. London: Routledge; 2016. [DOI: 10.4324/9781315672953]

- Taylor CDJ, Bee P, Haddock G. Does schema therapy change schemas and symptoms? A systematic review across mental health disorders. Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2017; 90(3):456-79. [DOI:10.1111/papt.12112] [PMID]

- Pace TM. Schema Theory: A framework for research and practice in psychotherapy. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1988; 2(3):147-63. [DOI:10.1891/0889-8391.2.3.147]

- Feste KA. Frame theory. In: America responds to terrorism. The evolving American presidency series. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; 2011. [DOI:10.1057/9780230118867_2]

- Jarvis GE, Kirmayer LJ. Situating mental disorders in cultural frames. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2021. [DOI:10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.627]

- Halle R. Exploring the effect of self-monitoring of grief reactions in recently bereaved people on depression by means of experience sampling methodology: A randomized controlled trial [MA thesis]. Drienerlolaan: University of Twente; 2023. [Link]

- Haertl KL, Ero-Phillips AM. The healing properties of writing for persons with mental health conditions. Arts & Health. 2019; 11(1):15-25. [DOI:10.1080/17533015.2017.1413400] [PMID]

- Ruini C, Mortara CC. Writing technique across psychotherapies-from traditional expressive writing to new positive psychology interventions: A narrative review.Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. 2022; 52(1):23-34. [DOI:10.1007/s10879-021-09520-9] [PMID]

- Pikalov A. Online counseling: A Handbook for mental health professionals. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005; 162(3):638. [DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.638]

- Allen SF, Wetherell MA, Smith MA. Online writing about positive life experiences reduces depression and perceived stress reactivity in socially inhibited individuals. Psychiatry Research. 2020; 284:112697. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112697] [PMID]

- Harris J. Signifying pain: Constructing and healing the self through writing. New York: State University of New York Press; 2012. [Link]

- Khabbache H, Cherqui A, Ouazizi K, Ait D, Bahrami Zadeh MY, Bragazzi NL, et al. The contribution of subjective wellbeing to the improvement of the academic performance of university students through time management as a mediator factor: A structural equation modeling. Journal of Health and Social Sciences. 2023; 8:308-22. [Link]

- Moser KS. Metaphors as symbolic environment of the self: How self-knowledge is expressed verbally. Current Research in Social Psychology. 2007; 12(11):151-78. [Link]

- Kilkku N, Karlsson B. Educational aspects in advanced mental health nursing practice. In: Higgins A, Kilkku N, Kort Kristofersson G, editors. Advanced practice in mental health nursing. Cham: Springer; 2022. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-031-05536-2_15]

- Khabbache H, Ouaziz K, Bragazzi NL, Alaoui ZB, Mrabet R. Thinking about what the others are thinking about: An integrative approach to the mind perception and social cognition theory. Cosmos and History: The Journal of Natural and Social Philosophy. 2020; 15(2):266-95. [Link]

- Khabbache H, Candau J, Bragazzi N. [When the patient becomes the therapist (French) [internet]. 2015 [Updated 2024 April]. Available from: [Link]

- Seymour-Walsh AE, Bell A, Weber A, Smith T. Adapting to a new reality: COVID-19 coronavirus and online education in the health profession. Rural and Remote Health. 2020; 20: 6000. [DOI:10.22605/RRH6000]

- Simons PRJ. Constructive learning: The role of the learner. Des Environ Constr Learn. In: Duffy TM, Lowyck J, Jonassen DH, Welsh TM, editors. Designing environments for constructive learning. Berlin: Springer; 1993. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-642-78069-1_15]

- Sackin P, Barnett M, Eastaugh A, Paxton P. Peer-supported learning. The British Journal of General Practice. 1997; 47(415):67-8. [PMID]

- Dollan B. Cultural relativism or eurocentrism? A historical perspective. Paris: University of Paris; 1999. [Link]

- Tirupati S. The principles and practice of psychiatric rehabilitation. Indian Journal of Mental Health and Neurosciences. 2018; 1(1):8-12. [DOI:10.32746/ijmhns.2018.v1.i1.1]

- Schiller D, Alessandra NC, Alia-Klein N, Becker S, Cromwell HC, Dolcos F, et al. The human affectome. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2024; 158:105450. [DOI:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2023.105450]

- Yildirim M, Turan Me, Albeladi Ns, Crescenzo P, Rizzo A, Nucera G, et al. Resilience and perceived social support as predictors of emotional well-being. Journal of Health and Social Sciences. 2023; 8:59-75. [Link]

Article type: Original Research Articles |

Subject:

Psychology

Received: 2024/01/17 | Accepted: 2024/02/8 | Published: 2024/03/1

Received: 2024/01/17 | Accepted: 2024/02/8 | Published: 2024/03/1

Send email to the article author