Volume 23, Issue 2 (June 2025)

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2025, 23(2): 217-232 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Acquadro Maran D, Varetto A, Begotti T, Rizzo A, Yıldırım M, Batra K, et al . Consequences and Coping Strategies Among Students and Workers Experiencing Stalking. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2025; 23 (2) :217-232

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2458-en.html

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2458-en.html

Daniela Acquadro Maran *1

, Antonella Varetto2

, Antonella Varetto2

, Tatiana Begotti1

, Tatiana Begotti1

, Amelia Rizzo3

, Amelia Rizzo3

, Murat Yıldırım4

, Murat Yıldırım4

, Kavita Batra5

, Kavita Batra5

, Hicham Khabbache6

, Hicham Khabbache6

, Francesco Chirico7

, Francesco Chirico7

, Antonella Varetto2

, Antonella Varetto2

, Tatiana Begotti1

, Tatiana Begotti1

, Amelia Rizzo3

, Amelia Rizzo3

, Murat Yıldırım4

, Murat Yıldırım4

, Kavita Batra5

, Kavita Batra5

, Hicham Khabbache6

, Hicham Khabbache6

, Francesco Chirico7

, Francesco Chirico7

1- Department of Psychology, University of Torino, Torino, Italy.

2- City of Science and Health, Turin, Italy.

3- Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Messina, Messina, Italy.

4- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Science and Letters, Agri Ibrahim Cecen University, Ağrı, Turkey. & Psychology Research Center, Khazar University, Baku, Azerbaijan.

5- Department of Medical Education, Kirk Kerkorian School of Medicine at UNLV, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, United States.

6- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Arts and Human Sciences Fès-Saïss, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, Fes, Morocco. & Director of the Unesco Chair, Lifelong Learning Observatory, Hamburg, Germany.

7- Post-graduate School in Occupational Health, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Rome, Italy.

2- City of Science and Health, Turin, Italy.

3- Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Messina, Messina, Italy.

4- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Science and Letters, Agri Ibrahim Cecen University, Ağrı, Turkey. & Psychology Research Center, Khazar University, Baku, Azerbaijan.

5- Department of Medical Education, Kirk Kerkorian School of Medicine at UNLV, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, United States.

6- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Arts and Human Sciences Fès-Saïss, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, Fes, Morocco. & Director of the Unesco Chair, Lifelong Learning Observatory, Hamburg, Germany.

7- Post-graduate School in Occupational Health, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Rome, Italy.

Full-Text [PDF 718 kb]

(312 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1574 Views)

Full-Text: (172 Views)

Introduction

The etymological term stalking goes back to the language of sport hunting. The term “stalking” refers to pursuing prey that moves stealthily [1], a temporally concealed approach and pursuit with the intent to capture and harm. Applied to interpersonal relationships, this definition means that someone who pursues another person does so with threatening or harmful intent [2]. Meloy [3] asserts that stalking is typically described as malicious and harassing over an extended period, in which a person intentionally acts on another person whose safety is threatened. This definition includes two elements: Threats to safety and the repetition of harassment. Many stalking behaviors can be equated to those of a normal courtship, intentional or not. Petherick asserts that the experience of fear for one’s safety and the duration and persistence of the behavior are some discriminatory features that may contribute. The first is caused by the stalker’s inability or unwillingness to accept the reality of the facts, i.e. the victim is not interested in the relationship. The second is specifically related to repeated harassment; it is this act that identifies the difference between stalking and unwanted courting by an ex-partner, a rejected suitor, or a stranger. Two main characteristics of stalking are repetition over time and the unwanted nature of the stalker’s behaviors. Stalking behaviors are described as persistent harassments in which the stalker establishes various forms of surveillance, communication, control, and unwanted contact with another person. These behaviors are perceived as threatening and may affect the victim’s quality of life [4, 5]. Fear emerges as a critical element in many definitions of stalking, although it is controversial given the difficulties in operationalizing it [6, 7]. According to Sheridan et al. [8] these behaviors can be routine and innocuous acts (e.g. offering gifts, making phone calls, sending written messages) or intimidating acts (e.g. stalking, sending threatening messages) that negatively impact the victim’s daily life. Stalking behaviors tend to escalate in frequency and aggressiveness and may be accompanied by other forms of violence, particularly psychological, physical, and sexual threats and aggression [9]. Spitzberg and Cupach [10] identified eight strategies that stalkers use to harass: Hyper-intimacy, mediated contacts, interactional contacts, surveillance, invasion, harassment and intimidation, coercion and threat, and aggression. Hyperintimacy refers to a range of excessive or inappropriate behaviors (e.g. offering gifts) toward victims. Mediated contacts are forms of communication, including those using information-communication technology (e.g. email, cell phone). Interactive contacts include direct contact (e.g. physical approach, showing up at places where the victim usually is) or indirect contact (e.g. approaching people known to the victim). Surveillance strategies involve monitoring and attempting to obtain information about victims. Invasion tactics include invading and violating the victim’s privacy (e.g. property invasion, theft). Harassment and intimidation are a series of verbal or nonverbal threats designed to upset the victim (e.g. spreading rumors). Coercion and threats consist of behaviors intended to cause harm to the victim (e.g. threats against the victim’s life or that of third parties). Finally, aggression includes intentional acts that cause harm to the victim or third parties (e.g. physical or sexual violence) [11].

Prevalence of the phenomenon

The National Violence Against Women Survey, a representative study in the United States of experiences of violence, including stalking, reports that 8% of women and 2% of men have been stalked at some point in their lives [12]. A meta-analysis of 175 studies on stalking found lifetime prevalence rates for male victims ranging from 2% to 13% and for female victims ranging from 8% to 32% [13]. A particular group of workers were involved in studies on the phenomenon, suggesting that stalking in the workplace is not uncommon. Pathé and Mullen’s [14] study of 100 stalking victims found that 25% first met their stalker at work. Purcell et al. [15] studied 40 female stalkers and found that 58% targeted professional contacts or others they first met at work. In their study of 371 stalking victims in the United Kingdom, Sheridan et al. [16] found that 16% of victims reported that stalkers were in the workplace. Moreover, there is evidence in the literature from surveys of journalists, teachers, politicians, trade :union:ists, university professors, health care professionals, and others. For example, a survey of 493 German journalists showed that the frequency of the phenomenon related to professional activity is 2.19% [17], while the percentage among 721 English teachers is 5.10% [8, 10]. Morgan and Kavanaugh’s [18] study showed that of 934 US university teachers, 33% were stalking victims. A survey conducted by Galeazzi et al. [19] in Italy of 361 healthcare professionals found that the percentage of victimization was 11%, with stalkers being patients in 90% of cases. In their systematic review, Harris et al. [13] found that the prevalence of victimization among mental health professionals varied between 10.2% and 50%.

University students are considered the most vulnerable population to stalking and have higher prevalence rates than the general population [20]. Sheridan et al. [8], reported an average frequency of victimization of 24%, similar to that found in an Italian sample [21]. The prevalence rates range from 8-25% for women and 2-13.3% for men. In a systematic review by Pires, et al. [22], prevalence indicators for lifetime victimization among students varied from 12% [23] to 96% [24]. The prevalence indicator for victimization since the beginning of college was 19.9% [25]. Fisher et al. [26] found a prevalence of 15% of students who were victims of stalking, using the last year as the reference period. Finally, Jordan et al. [27]. used three reference periods for stalking victimization in their study: 40.4% of stalking victimization occurred over a lifetime, 18% of victimization occurred since the student entered college, and 11.3% of victimization occurred in the past year. Data on the prevalence of cyberstalking in the college population only consider the reference period of lifetime victimization, ranging from 13% [28] to 74.8% [29]. Authors, such as Menard et al. [30] and Fedina et al. [31] argue that stalking may develop since this population is mostly young adults and singles who have a desire for independence and predictable routines on university campuses [32].

Consequences of the victimization

Several studies that addressed the impact of stalking on victims reported that mental health was most affected (e.g. anxiety, depressed mood, anger) [33-35]. In addition to mental health, physical consequences (e.g. sleep disturbances, headaches, and muscle weakness) were reported [5, 36, 37]. Fissel et al. [38] also indicated consequences for the victim’s lifestyle (e.g. losing confidence in others). For students, consequences affected different areas: Economic (e.g. changing cell phone number or residence, investing in software to protect technology), social (e.g. social isolation), professional/academic performance (e.g. absence from work or classes, changing or quitting jobs, leaving the University) [39], and the victim’s mental health (e.g. feeling threatened for safety, anger, anxiety, fear) [31]. Paullet et al. [28] also pointed to physical health (e.g. sleep disturbances, fatigue, and headaches) as one of the most affected areas [40].

Coping strategies

Victims most frequently activated sources of informal support (i.e. family and friends) [41-43]. At the same time, studies reported that victims did not report these behaviors to formal sources of support (i.e. security forces, and health professionals) [44-46]. However, Sheridan et al. [16] showed that workers victims experience specific stalker tactics, such as threats of termination and manipulation of workplace practices to gain contact with the target. Concerning student victimization experiences, studies reported that informal sources of support were most frequently activated by victims [44]. In their study, Cass and Mallicoat [47] found several reasons why students do not formally report their stalking victimization, including a sense of shame, especially among those who had a prior intimate relationship with the stalker, and the belief that stalking is not serious enough to report unless it involves persistent threats or physical incidents. The lack of help-seeking behavior by students regarding stalking masks the actual and perceived prevalence and severity of stalking in this population.

Purpose of the present study

In Italy, an anti-stalking law was added to the Penal Code in 2009 (Art. 612 bis). The law defines the offence as “constant threats or harassment of another person to such an extent that a serious, persistent state of anxiety or fear is created, or that the victims have a well-founded fear for their safety or the safety of relatives or other persons connected to the victims by kinship or emotional ties, or that the victims are forced to change their living habits.” Data from the Eurispes [48] report indicated that approximately 1 in 10 citizens reported having experienced stalking. This phenomenon increased by 1.4% compared to 2020. These results are consistent with those from 2014, when the number of stalking victims was 9.9% [49]. The highest percentage of stalking victims was found in the 18-24 age group (13%), while the percentage in other age groups was around 9%. Victims report experiencing fear, anger, and confusion. A previous survey [50] found that the most common behaviors suffered by victims included direct contact (15.1%), sending messages and emails or phone calls or unwanted gifts (13.5%), and repeatedly asking for dates (13.1%). In 11.9% of cases, they waited outside the home or workplace, and in 9.5% of cases, victims were followed or spied on. In a few cases, the behavior consisted of damaging their belongings or threatening them or other close people. Fifty percent of victims reported defending themselves or waiting for the stalker to stop doing nothing. A total of 17.4% asked friends and relatives to intervene, while almost 2 in 10 victims (18.9%) chose to limit outings, hobbies, and socializing with friends. The strategy of reporting to someone is lower among victims aged 18 and 24, who reported it in 9.8% of cases. The older ones are more likely to report (16%) when they are victims of stalking. The 18–24-year-olds are also the ones who most often decide to defend themselves (in 41.5% of the cases): A rather high percentage compared to the other age groups.

Based on the literature and data from the Italian context, this study aims to compare the experience of victimization between students and workers. Therefore, the following objectives were formulated.

To identify behaviors that characterize stalking, students reported a greater number of behaviors (H1).

To determine the consequences experienced, students reported more and more severe physical and emotional symptoms than workers, including depressive and anxiety symptoms (H2).

To evaluate whether students are more likely to defend themselves than workers (H3).

This study aimed to examine the impact of different stalking behaviors on students and workers regarding physical and emotional symptoms (as we do not have a specific hypothesis on this topic, we analyzed it with an exploratory goal).

Materials and Methods

In this cross-sectional study, the participants were 561 self-identified stalking victims: 291 students (51.9%) and 270 workers (48.1%). Most were women (79.9%), and four did not indicate gender. The Mean±SD age of the participants was 29.26±10.37 years; range 18-70 years. Regarding marital status, most participants were single (39.6%), 29.2% were engaged, 12.8% were married, 7.8% lived in a partnership, 5.2% were divorced, and one person was widowed. 24 participants did not respond to this question. Two groups of victims of stalking were identified: Those who identified themselves as students and those who identified themselves as workers.

Measures

To measure behaviors that characterize the stalking experience, a modified Italian version of the network for surviving stalking questionnaire was used [51, 52]. The items included behaviors, such as unusual letters, phone calls, emails, harassment, threats, and physical assault (28 items, possible answer options: No=0; once a month=1; more than once a month=2; once a week=3; more than once a week=4; daily=5). As suggested by Spitzberg and Cupach [53], these behaviors were classified as follows:

1) Hyper-intimacy (four items: Offering gifts, sending unwanted material, unwarranted expressions of affection, and attempts to ingratiate themselves with the stalking target; range=0-20); 2) Mediated contact (four items: Letter, email, text message, social contact; range=0-20); 3) Interactional Contact (three items: Physical approach, showing up at home and university/workplace, approaching friends/colleagues/relatives; range=0-15); 4) Surveillance (three items: Following, photos, and moving around); 5) Invasion (three items: Visiting home, visiting workplace/university, property invasion; range=0-15); 6) Harassment and Intimidation (three items: Spreading rumours, harassment of the victim, and harassment of friends/colleagues/relatives; range=0-15); 7) Coercion and Threat (four items: Coercion, threats against the life of the victim, threats against the life of friends/colleagues/relatives, threats against the life of the victim’s pet; range=0-20), and 8) Aggression (four items: Physical violence, sexual violence, property damage, violence against the victim’s pet; range=0-20).

23 items from the Italian version of the stalking questionnaire were used to measure the consequences of the experience [54]. Twelve items examined physical symptoms (e.g. headaches, sleep disturbances, nausea, panic attacks; possible response options: Yes/no) and 10 items examined emotional symptoms (e.g. anger, fear, aggressiveness; possible response options: Yes/no).

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Italian short version of the Beck depression inventory (BDI) [55, 56]. It includes 13 items to classify symptoms and define different severity levels: No or minimal depression (scores 0–4), mild depression (5–7), moderate depression (8–15), and severe depression (>15) (in this study, Cronbach’s α was 0.92, indicating excellent internal consistency).

The state-trait anxiety inventory (STAI) was used to measure anxiety symptoms [57, 58]. It includes two subscales (STAI-Y1 and STAI-Y2; 20 items each) that assess how participants feel in the present moment (state anxiety) and how they feel most of the time (trait anxiety). The total scores ranged from 20 to 80, with 40 being the threshold for anxiety symptoms. The rating scale had different severity levels: Mild (40-50), moderate (51-60), and severe (>60). This study’s Cronbach’s α values were 0.91 for both subscales, indicating excellent internal consistency.

Coping strategies were measured using eight items from the Italian version of the stalking questionnaire [54]. The different coping strategies included collecting evidence, preparing a safety plan, increasing social contacts, increasing alcohol misuse, increasing drug misuse, increasing psychotropic substance use, decreasing social contacts, and getting a weapon (possible response options: Yes or no).

Procedure

All ethical guidelines were followed, including the legal requirements for research involving human subjects. Data were collected by research assistants whom the researchers had previously trained. Participants completed an anonymous questionnaire, which was given individually in paper form, and returned immediately after collection. They received an information letter, an informed consent form, and a questionnaire. The letter clearly explained the research objectives, voluntary nature of participation, data anonymity, and the results. The questionnaire took approximately 20 minutes to complete. All respondents participated in the study voluntarily and received no compensation.

Data analysis

SPSS software, version 29 was used to generate descriptive and inferential statistics. Descriptive measures (Mean±SD) were calculated for all test variables for the two groups of participants (students and workers) and their stalking experiences. χ2-tests were used to measure differences between stalking victims (students and workers) on episode characteristics (physical and emotional symptoms, severity of depression, and anxiety symptoms). Differences in stalking behavior, consequences of victimization (depression, state, and trait anxiety scores), and coping strategies were examined using descriptive statistics. Differences in scores were examined using the t-test. Differences were considered statistically significant when P<0.05. Correlations were calculated to examine the relationships between stalking behavior and physical and emotional symptoms, including depressive and anxiety symptoms. Simple linear regression was used to analyze which variables were the best predictors of anxiety and depression symptoms among victims. We summed the physical and emotional scores to perform the analyses and calculated the means to create dummy variables. Physical and emotional scores were considered dependent variables, and stalking behavior and physical and emotional symptoms were used as independent variables. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

Sociodemographic analysis

The results of the descriptive statistics showed that in the group of students, 79% are women. The students had an Mean±SD, 22.52±2.63. Most were single (55.3%), 37% were engaged, 3.9% lived in a partnership, 1.8% were married, and one was divorced. In the group of workers, the percentage of women is 82% (χ2=0.36, P=0.212). The workers have a mean age of 36.87±10.59; t=-20.77, P=0.001). Most were married (26.5%), 25.7% were single, 23.3% were engaged, 13% were in a partnership, 11.1% were divorced, and one was widowed.

Behaviors characterizing stalking

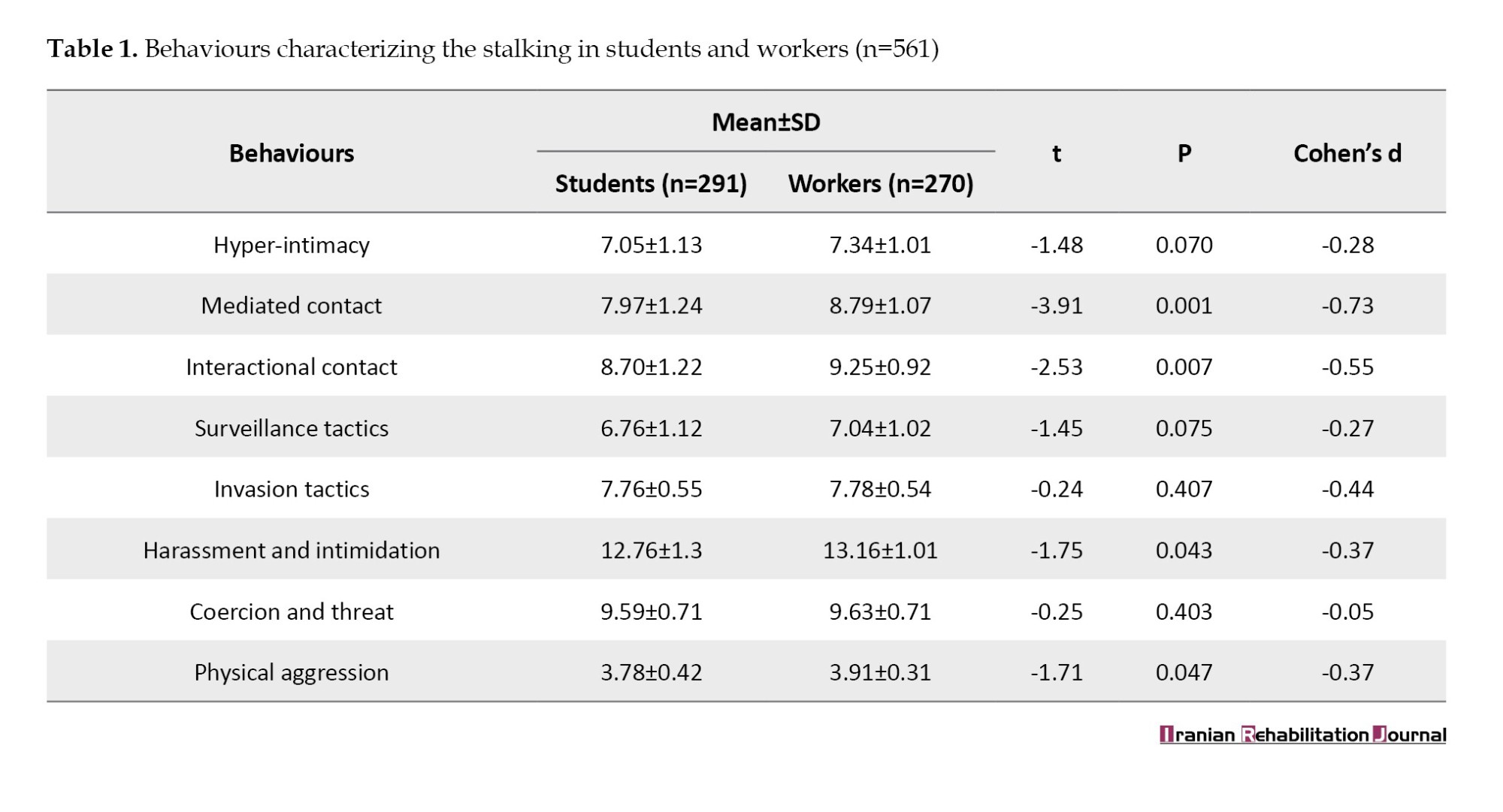

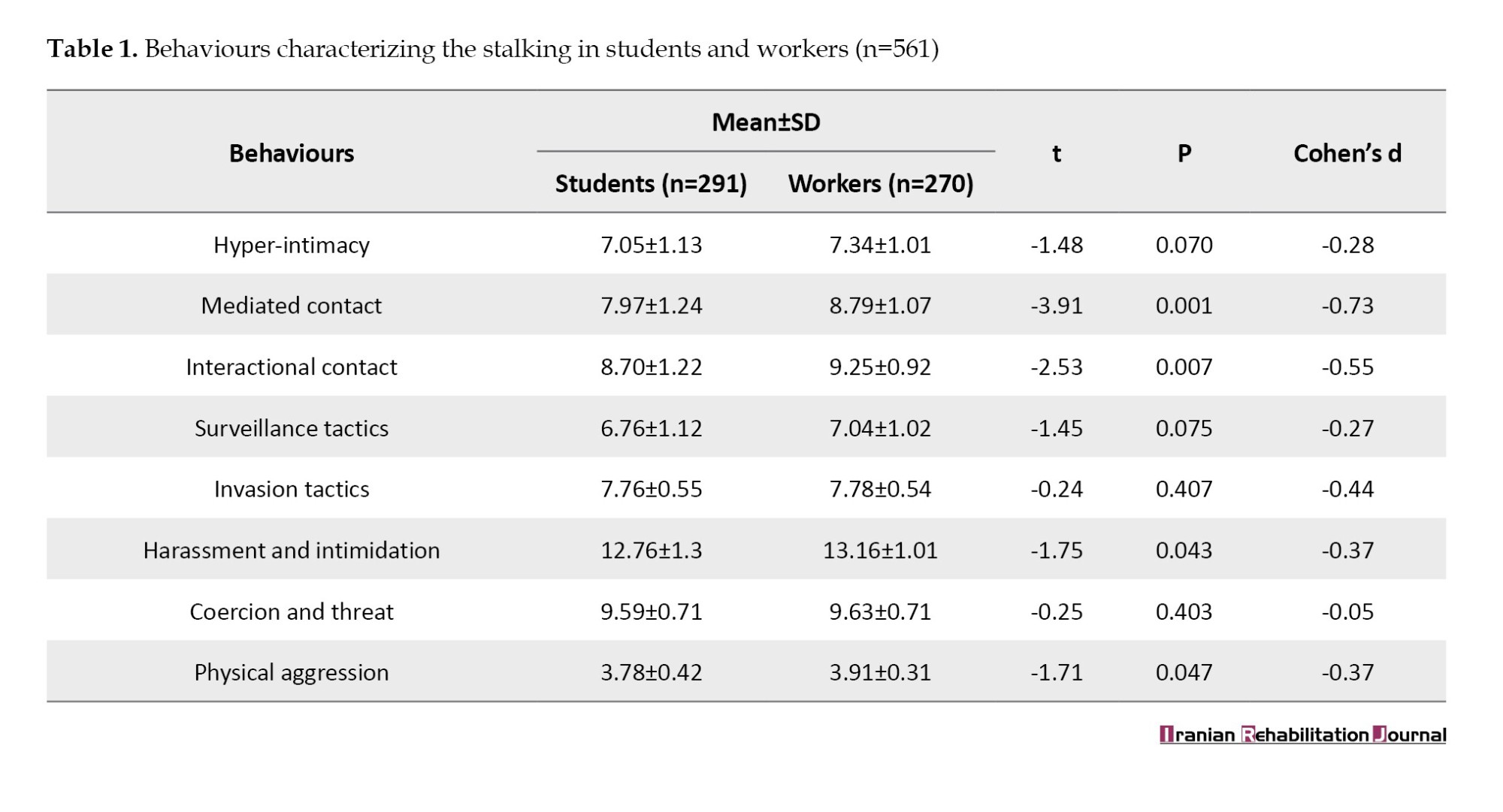

As shown in Table 1, workers were more likely to indicate certain behaviours than students. These behaviours are mediated contact, interactional contact harassment, and intimidation.

Physical and emotional symptoms

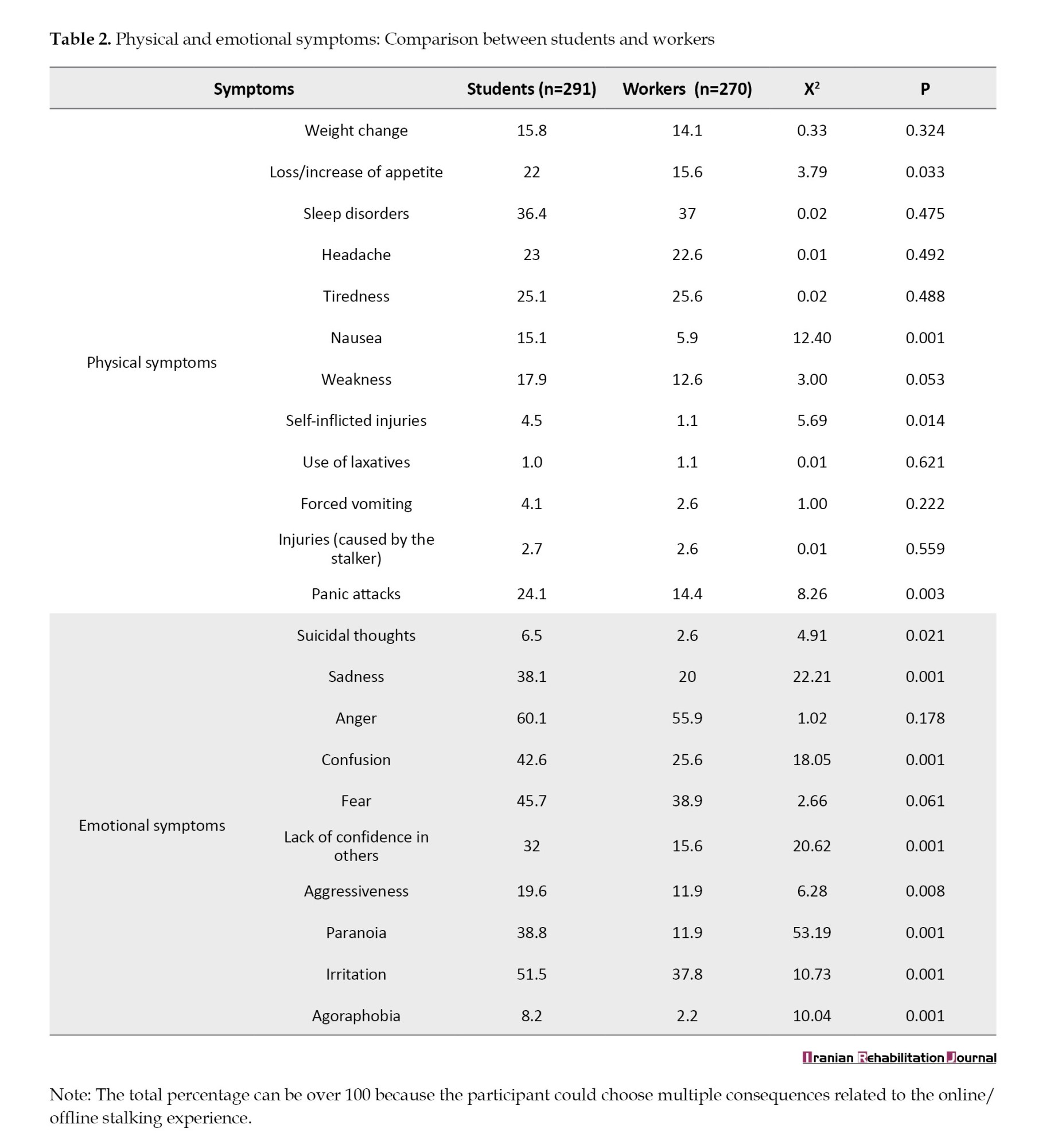

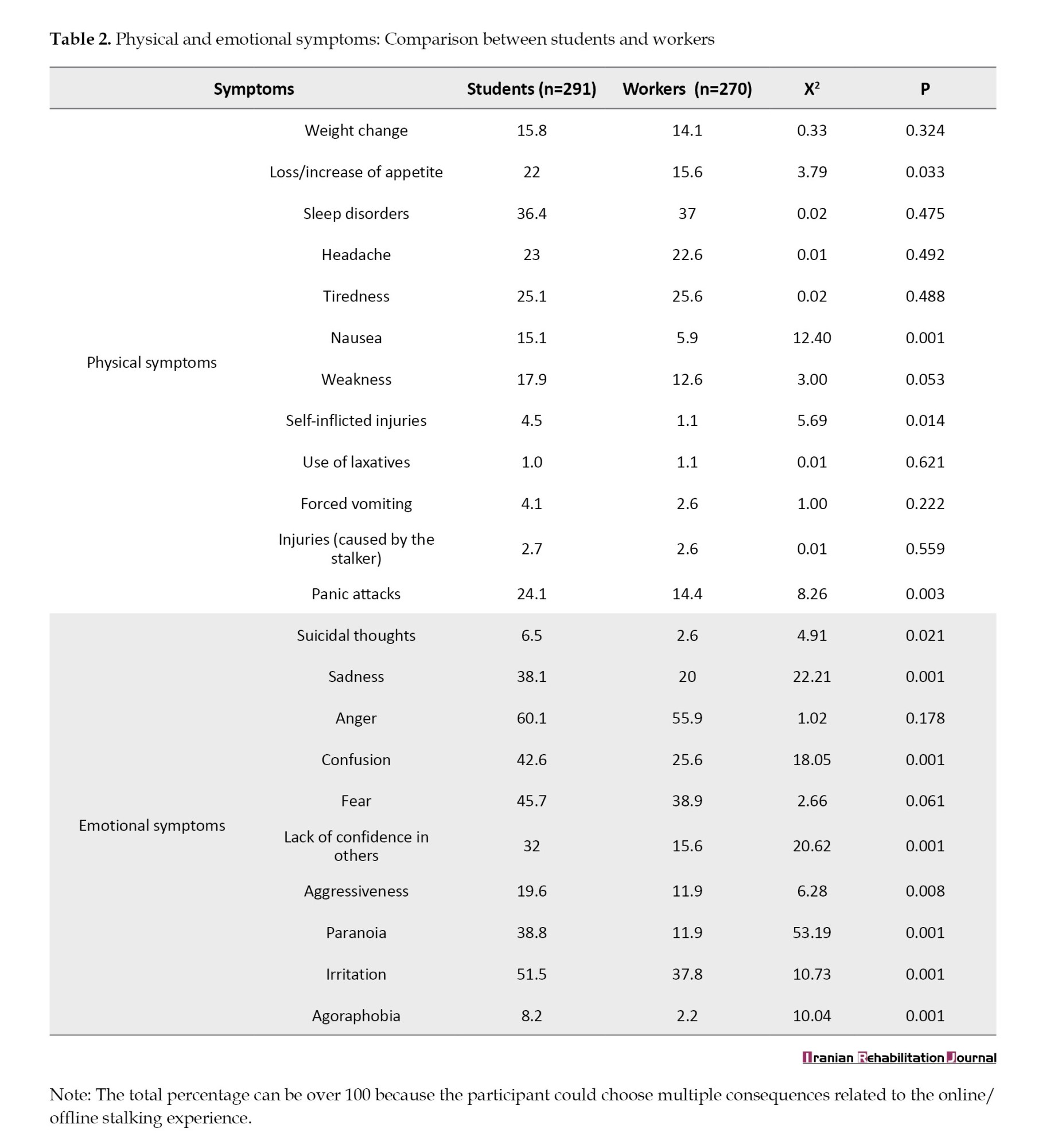

On average, students indicated 2.1±2.37 and workers indicated 1.86±2.13 physical symptoms (t=1.26; P=0.208; Cohen’s d=-0.063). Students are more prone to indicate some physical symptoms (loss/increase in appetite, nausea, self-inflicted injuries, and panic attacks) than are workers. Regarding emotive symptoms, students on average indicate 3.92±2.47 and workers indicate 2.83±1.99 symptoms (t=5.52; P=0.001; Cohen’s d=0.484). Students scored higher on most emotional symptoms (suicidal thoughts, sadness, confusion, lack of confidence in others, aggressiveness, paranoia, irritation, and agoraphobia) (Table 2).

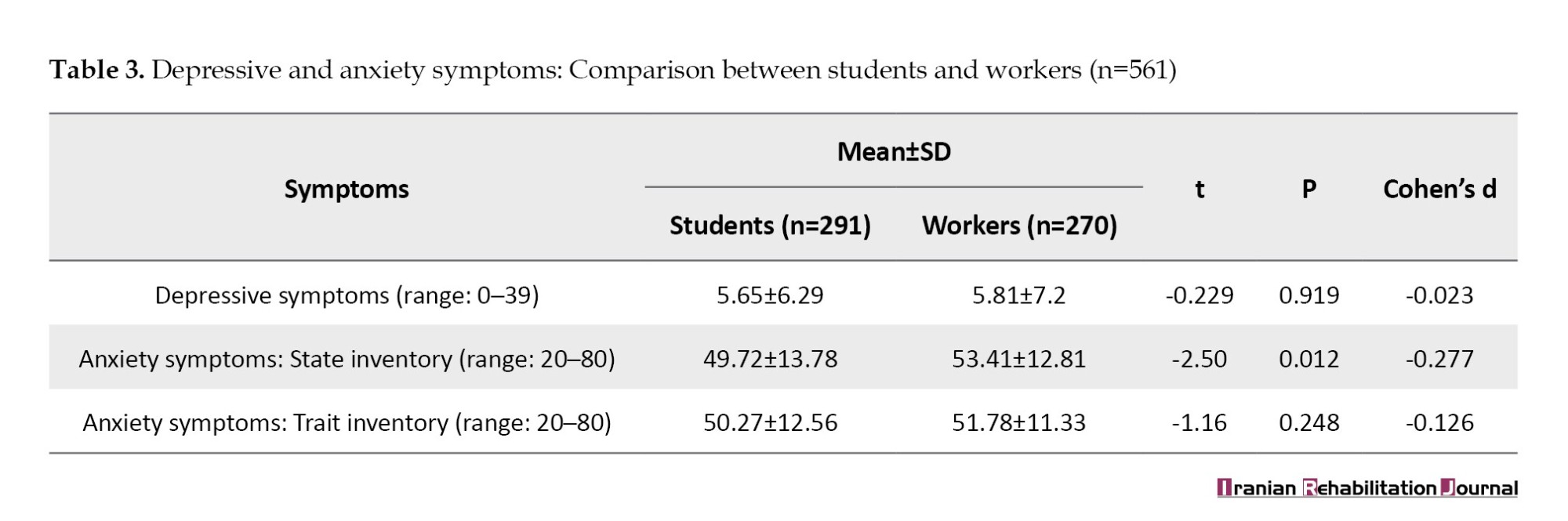

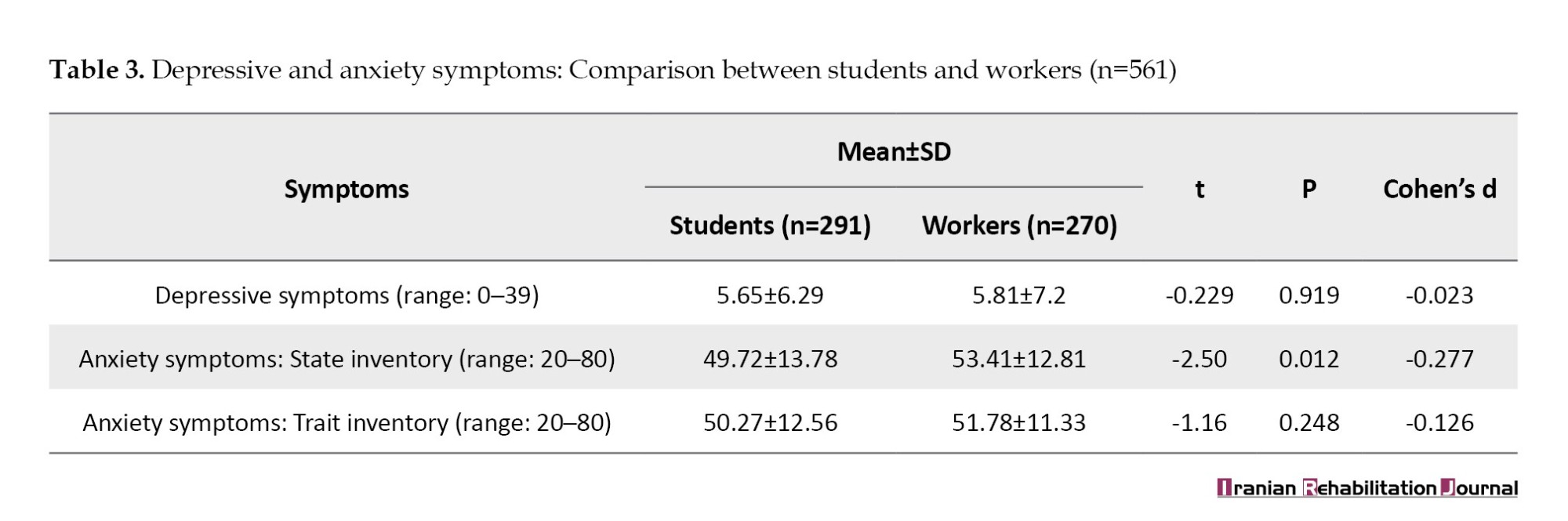

Regarding the symptoms of depression and anxiety, the results showed that on average, workers indicated a higher score for state anxiety (Table 3).

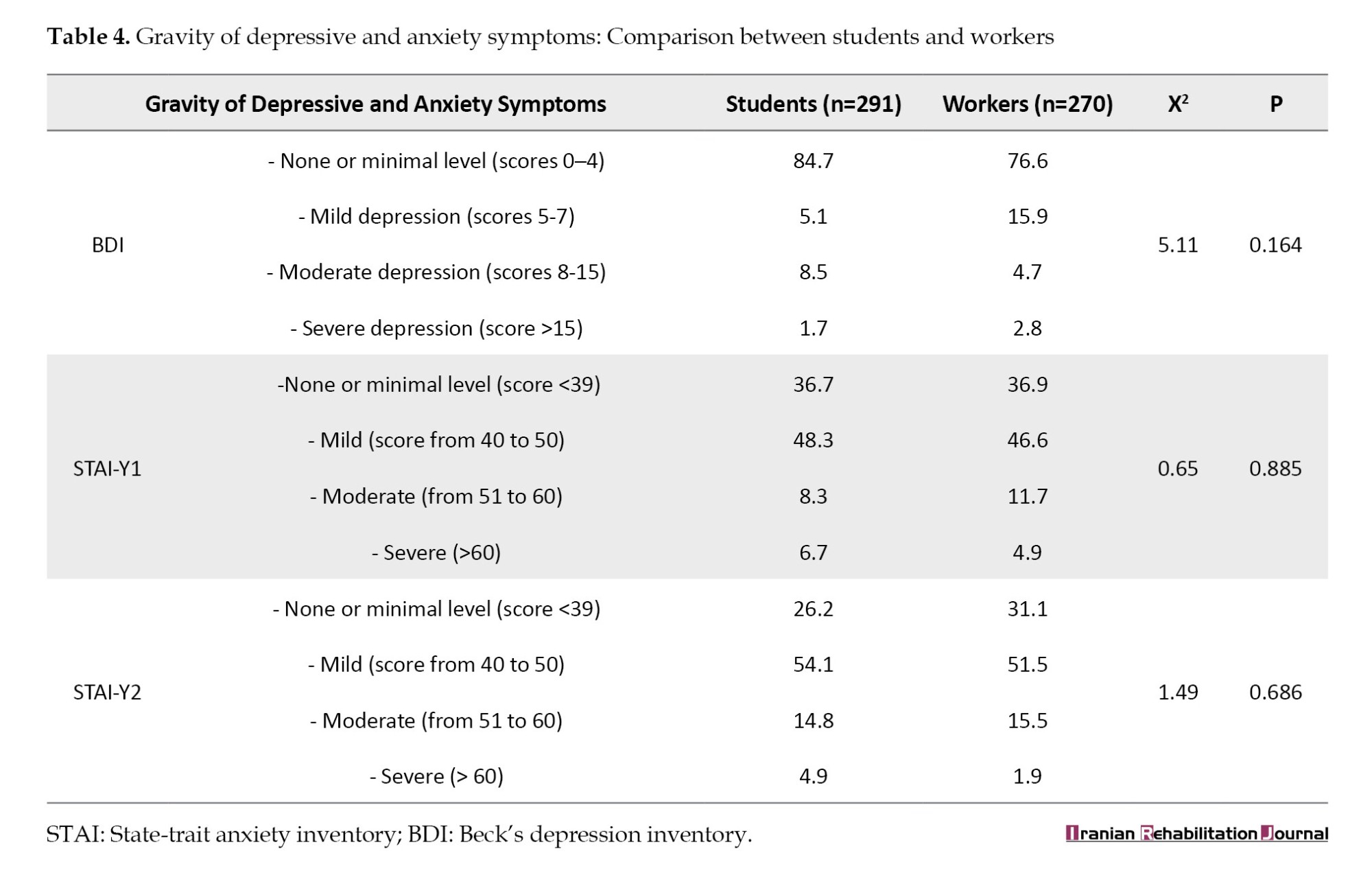

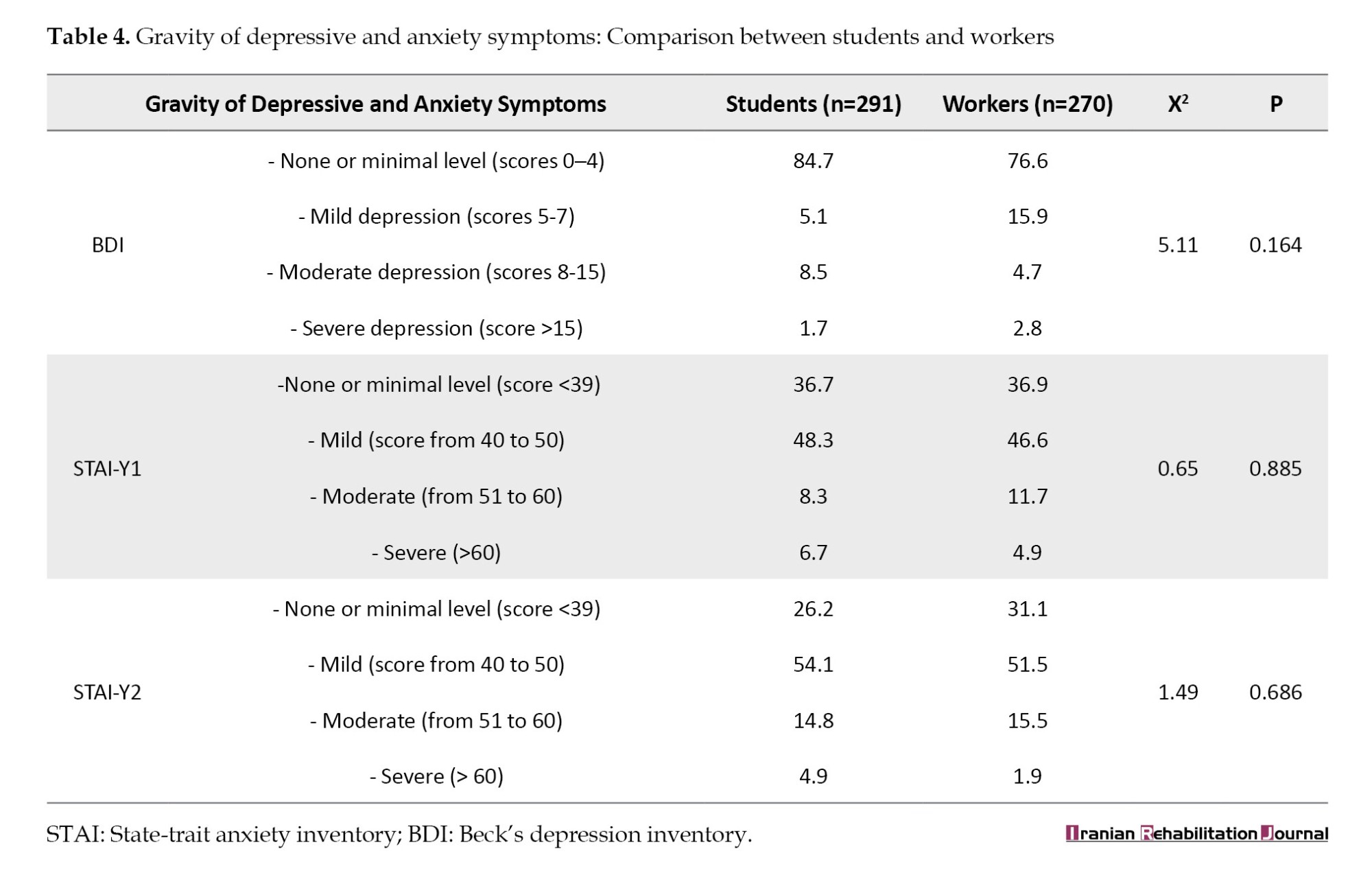

Specifically, the evaluation of scores for depressive symptoms and anxiety showed no differences between students and workers. It should be noted that the rating of depression is at a minimal level, while for anxiety, the condition that is suddenly most pronounced is mild anxiety symptoms (Table 4).

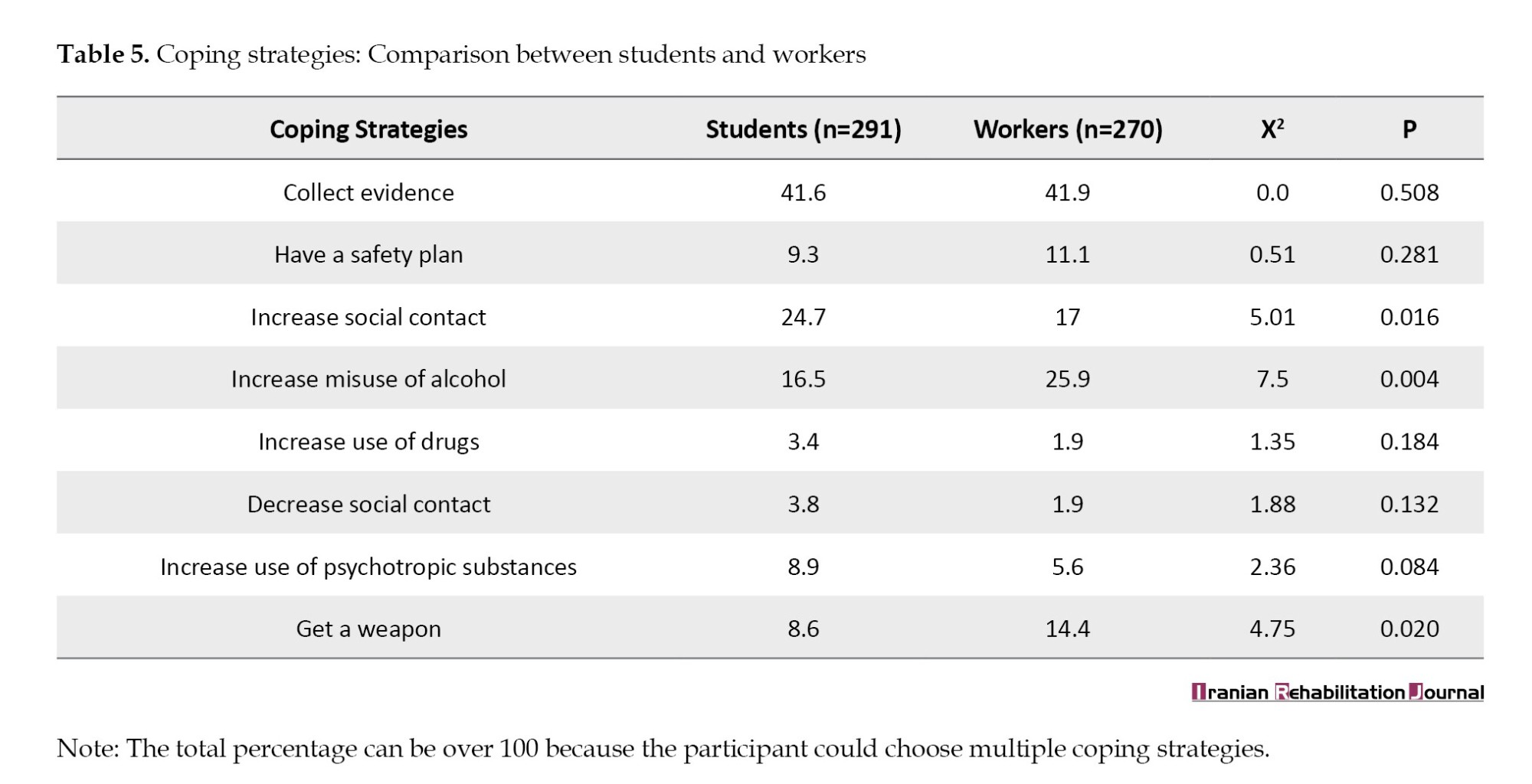

Coping strategies

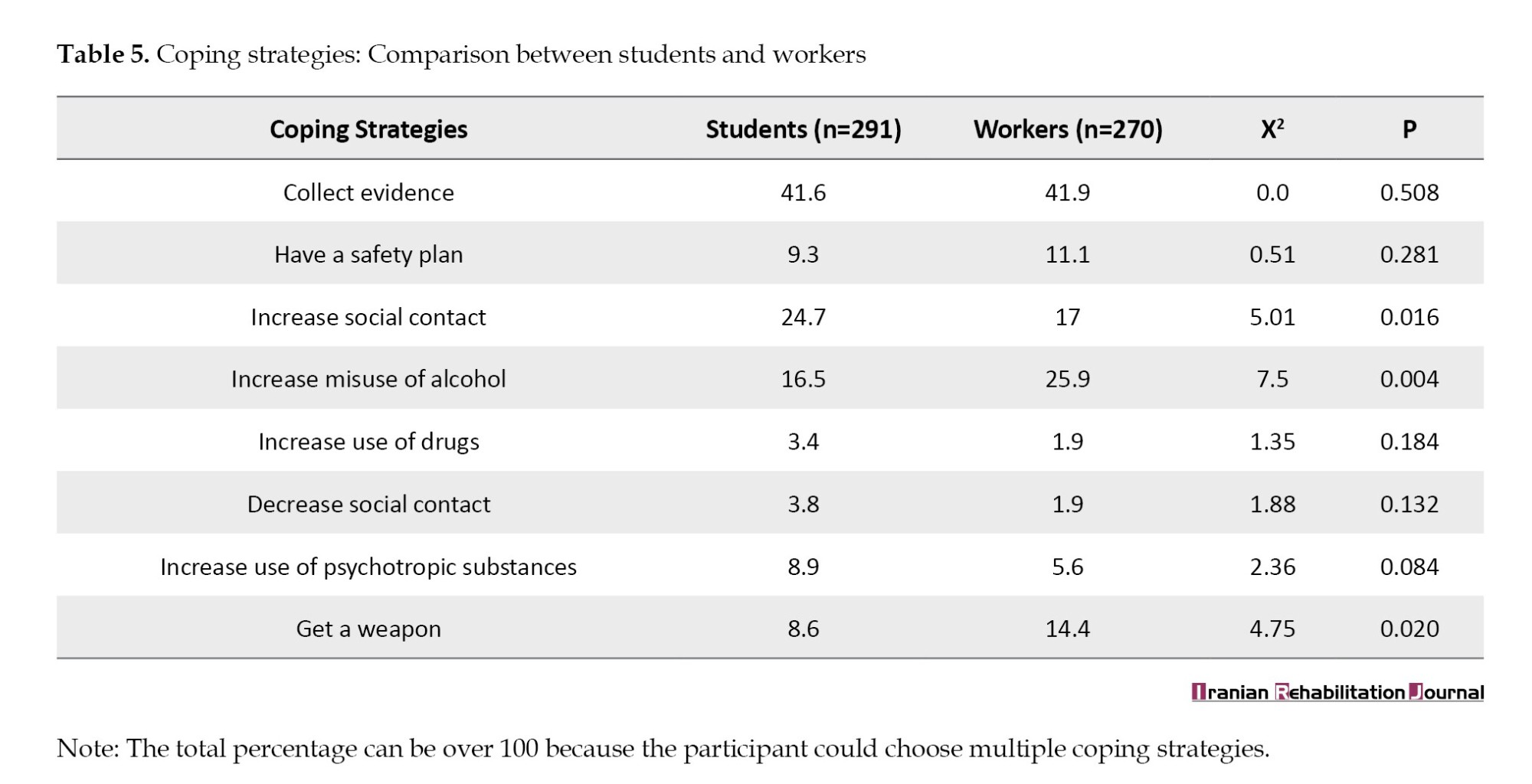

Analysis of the results for coping strategies revealed some differences in students’ and workers’ strategies. Students were more likely than workers to indicate an increase in social contact. In contrast, workers were more likely than students to indicate an increase in alcohol misuse and the strategy of getting a weapon (Table 5).

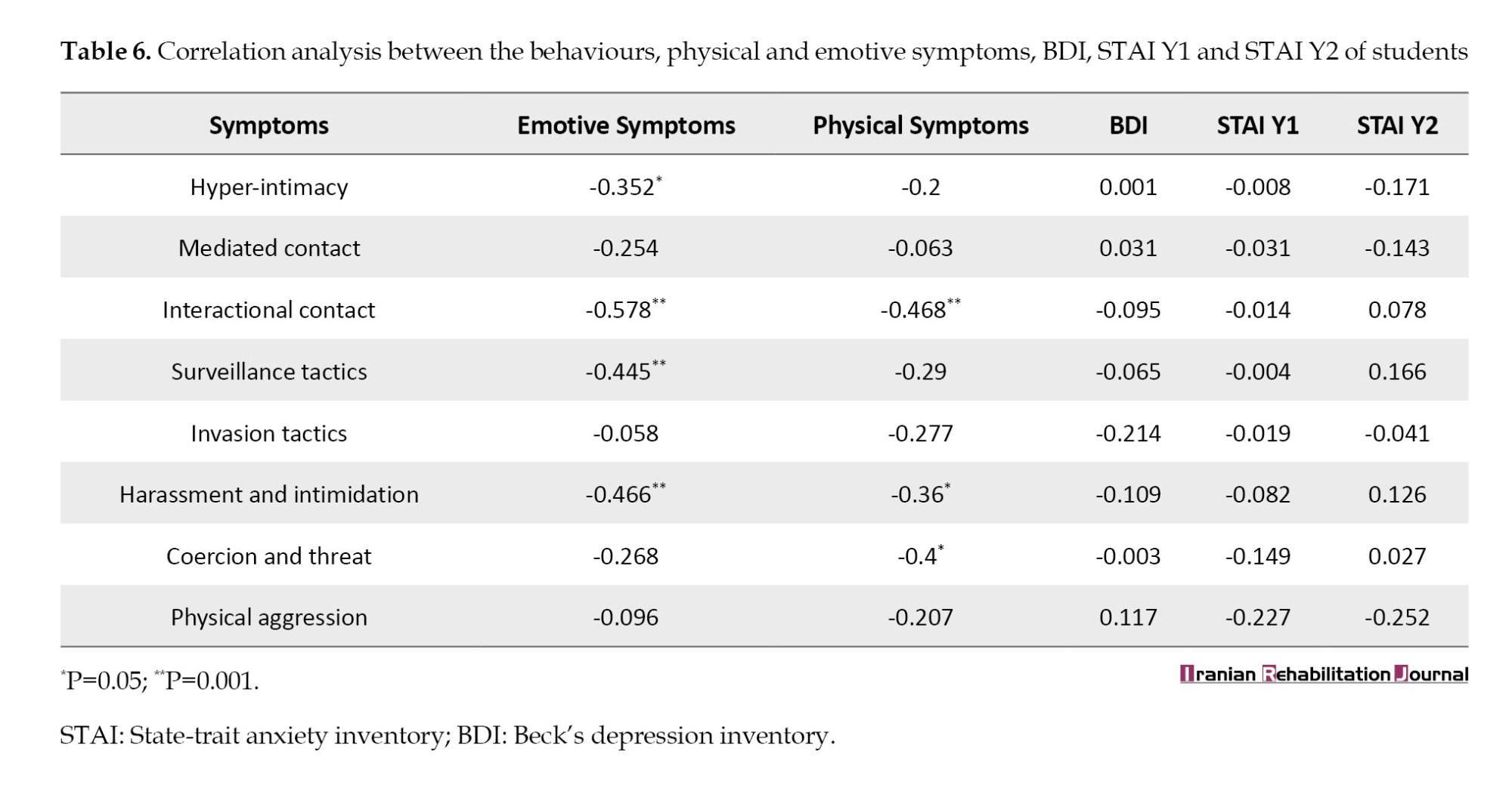

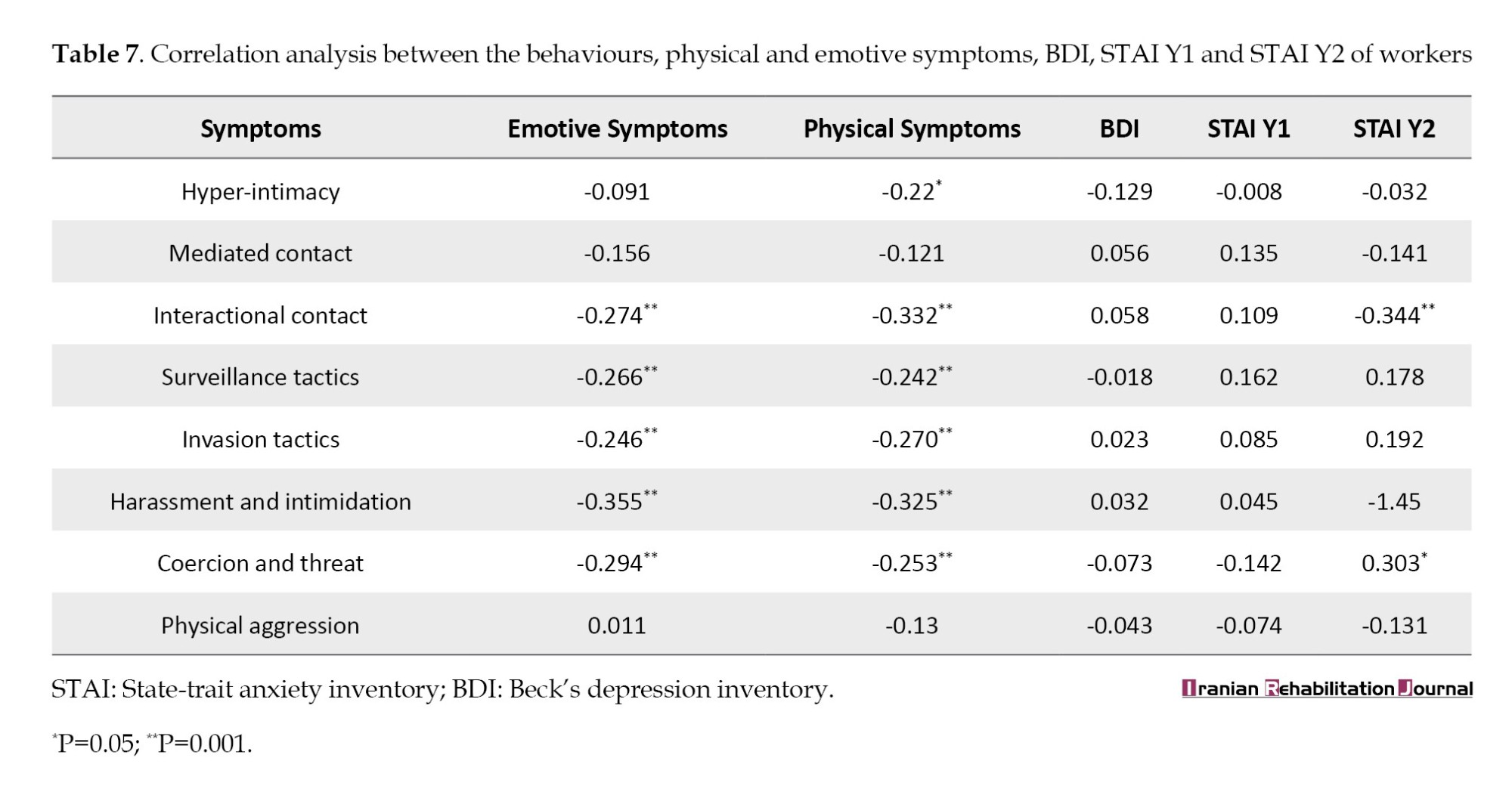

Inferential statistics

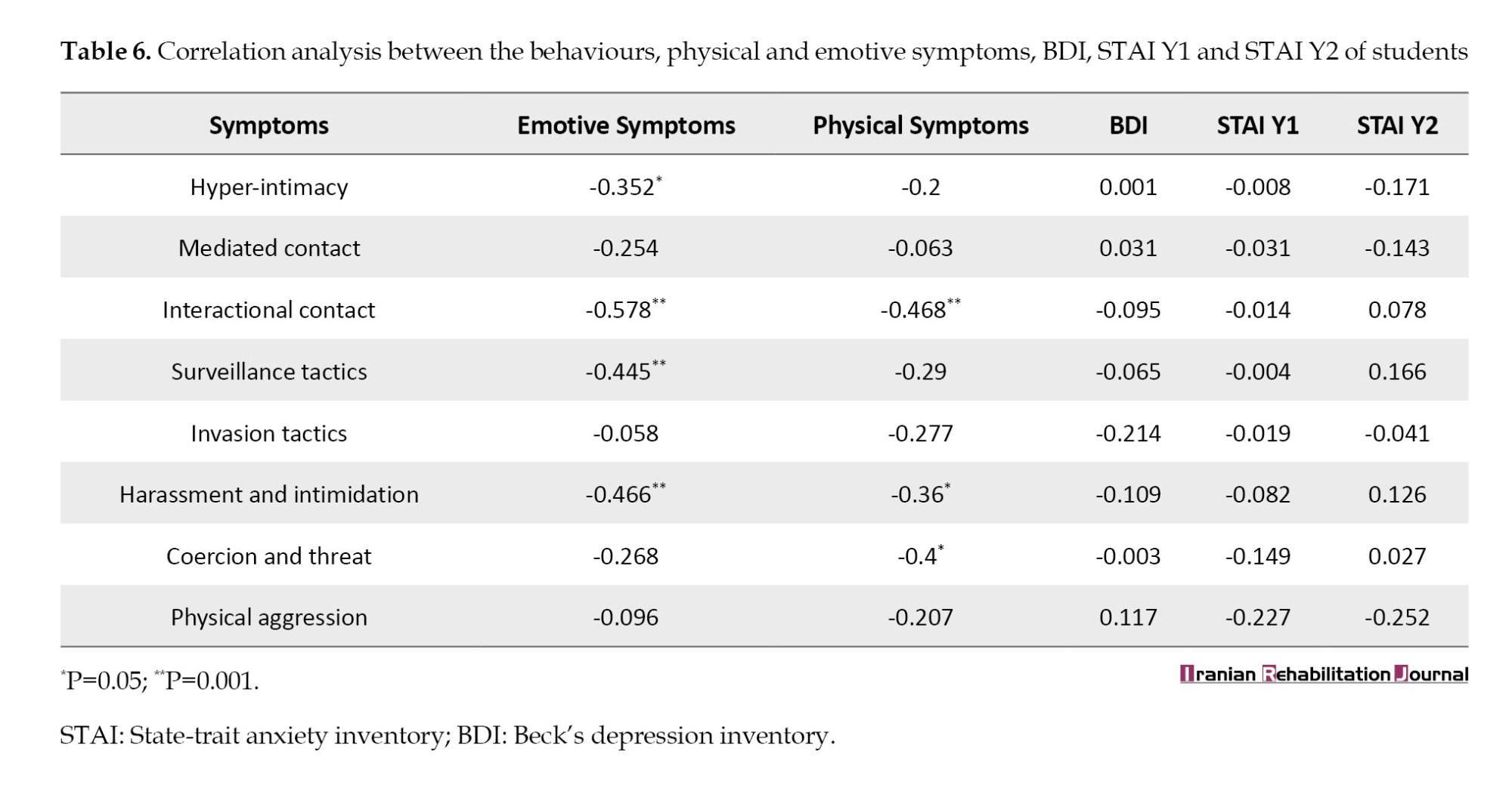

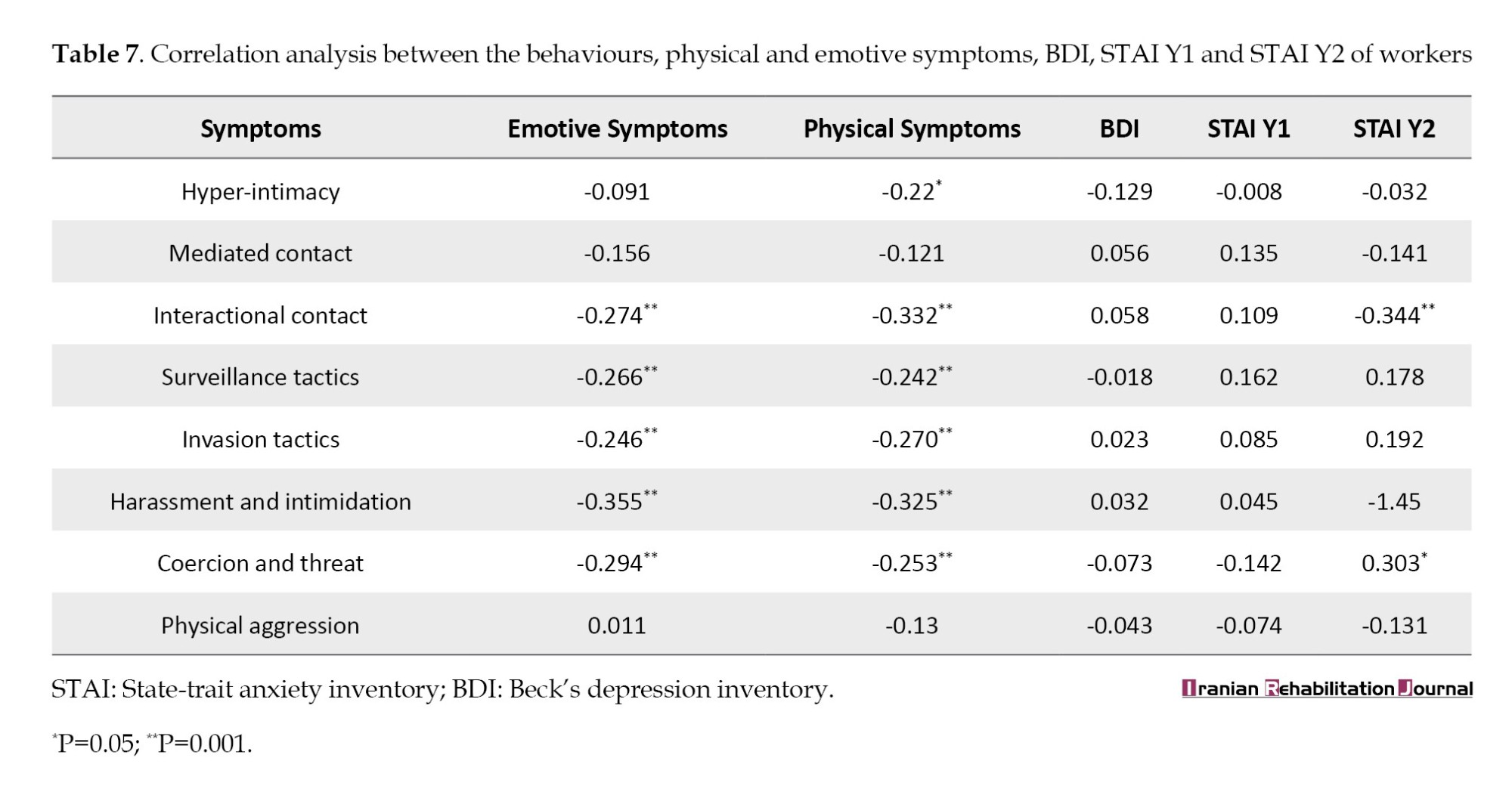

A correlation matrix was used to examine the relationships between stalking behaviors, physical and emotional symptoms, BDI, STAI from Y1, and STAI from Y2 in student and worker victims of stalking (Tables 6 and 7).

In students, the results show that as hyper-intimacy, interactional contact, surveillance tactics, harassment, and intimidation behaviors increase, emotional symptoms decrease, while physical symptoms decrease as interactional contact, harassment, intimidation, coercion, and threat behaviors increase. In workers, physical symptoms decrease as hyper-intimacy, interactional contact, surveillance tactics, harassment and intimidation, invasion tactics, and coercion, and threat behaviors increase, and emotional symptoms decrease as interactional contact, surveillance tactics, harassment and intimidation, invasion tactics, coercion, and threat behaviors increase. The only exception is trait anxiety, whose symptoms increase in workers as interactional contact, coercion, and threats increase.

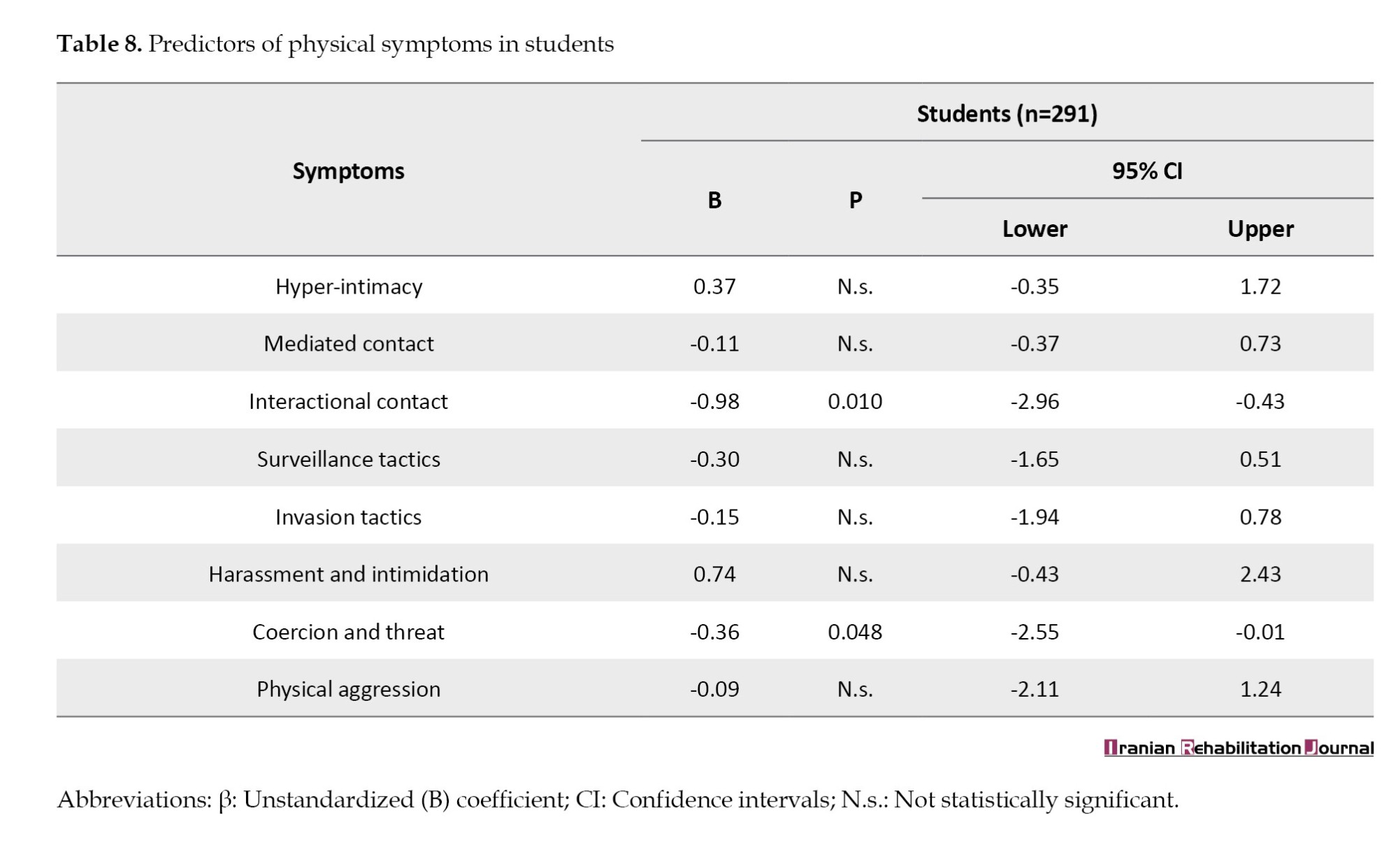

Linear regression

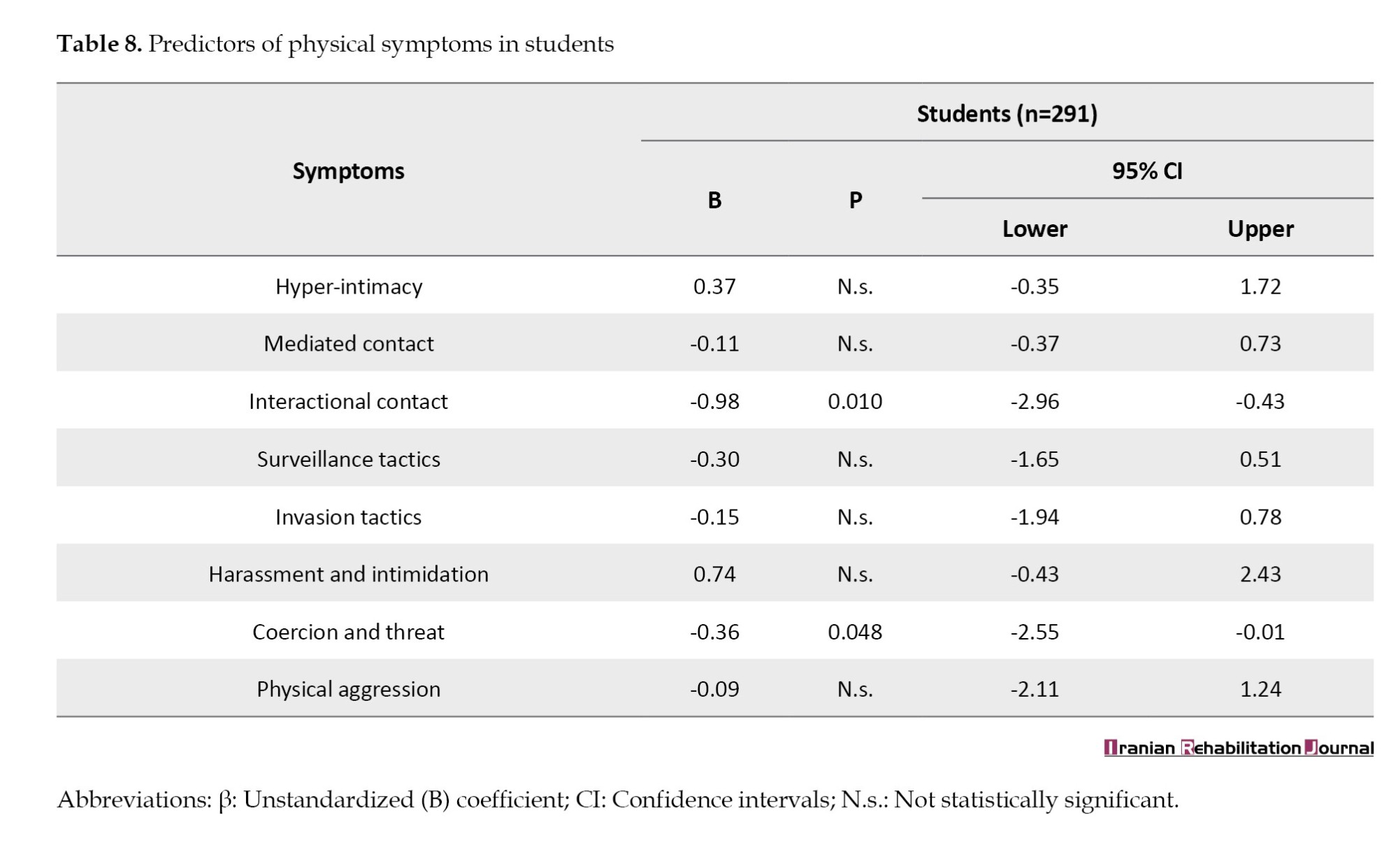

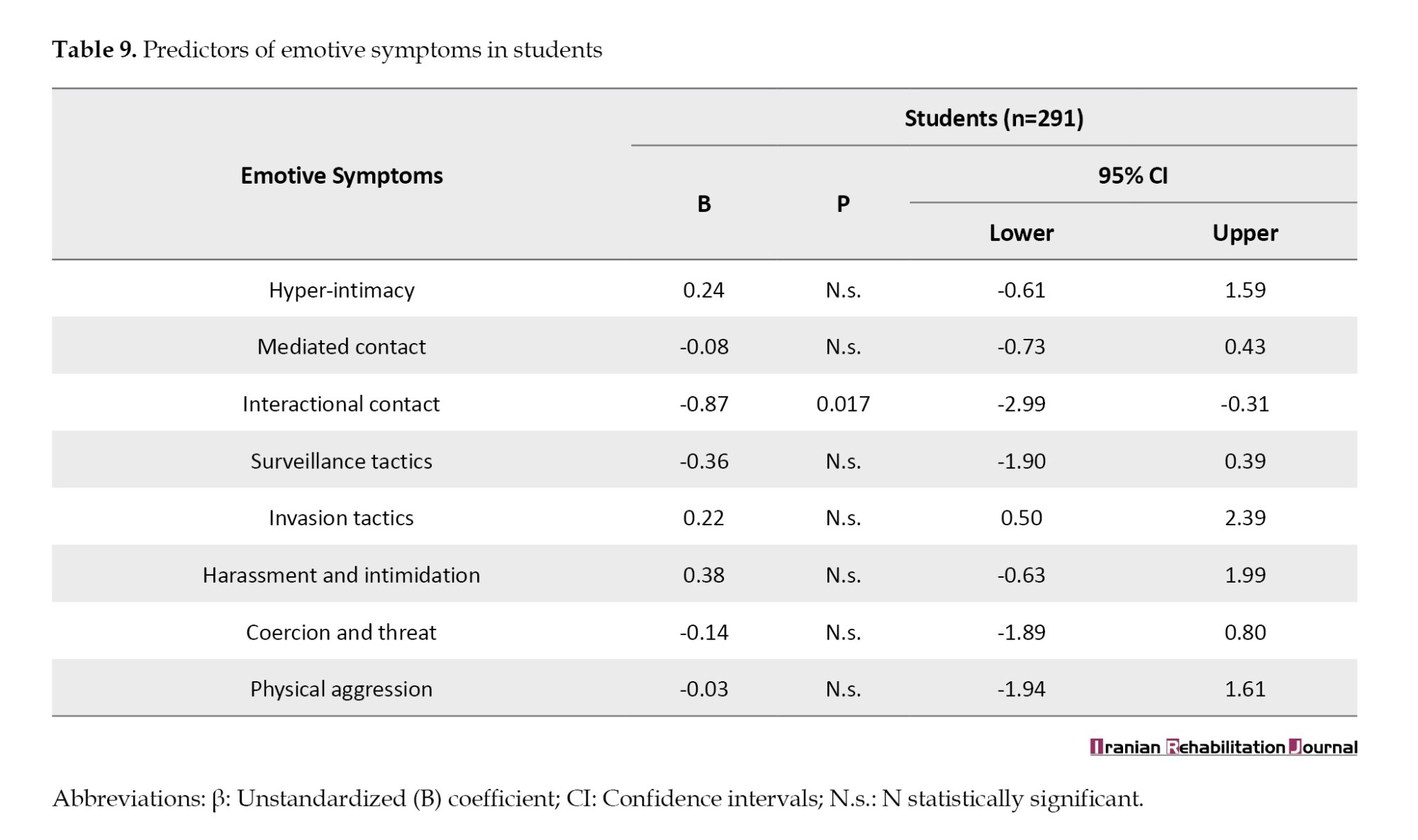

A linear regression analysis was conducted to predict the risk of physical and emotional symptoms in the victims (students and workers). Physical and emotional symptoms were divided into two categories (suffering: Yes/no) using the cut-off based on mean scores (students’ physical symptoms=2.11, emotional symptoms=3.92; workers’ physical symptoms=1.86, emotional symptoms=2.83).

The results showed that students’ physical symptoms were associated with interactional contact and coercion threats (Table 8).

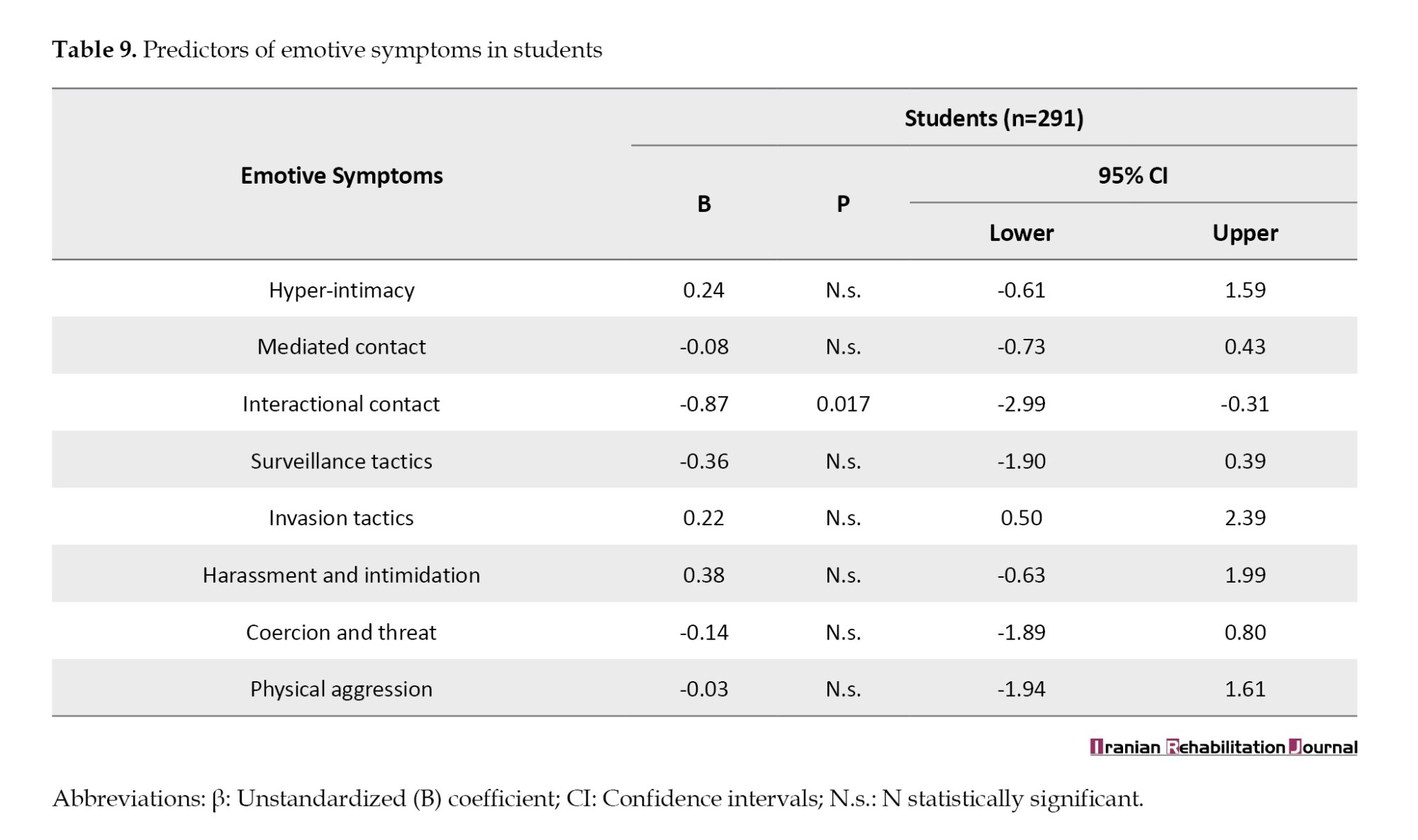

Emotional symptoms were associated with interactional contact (Table 9).

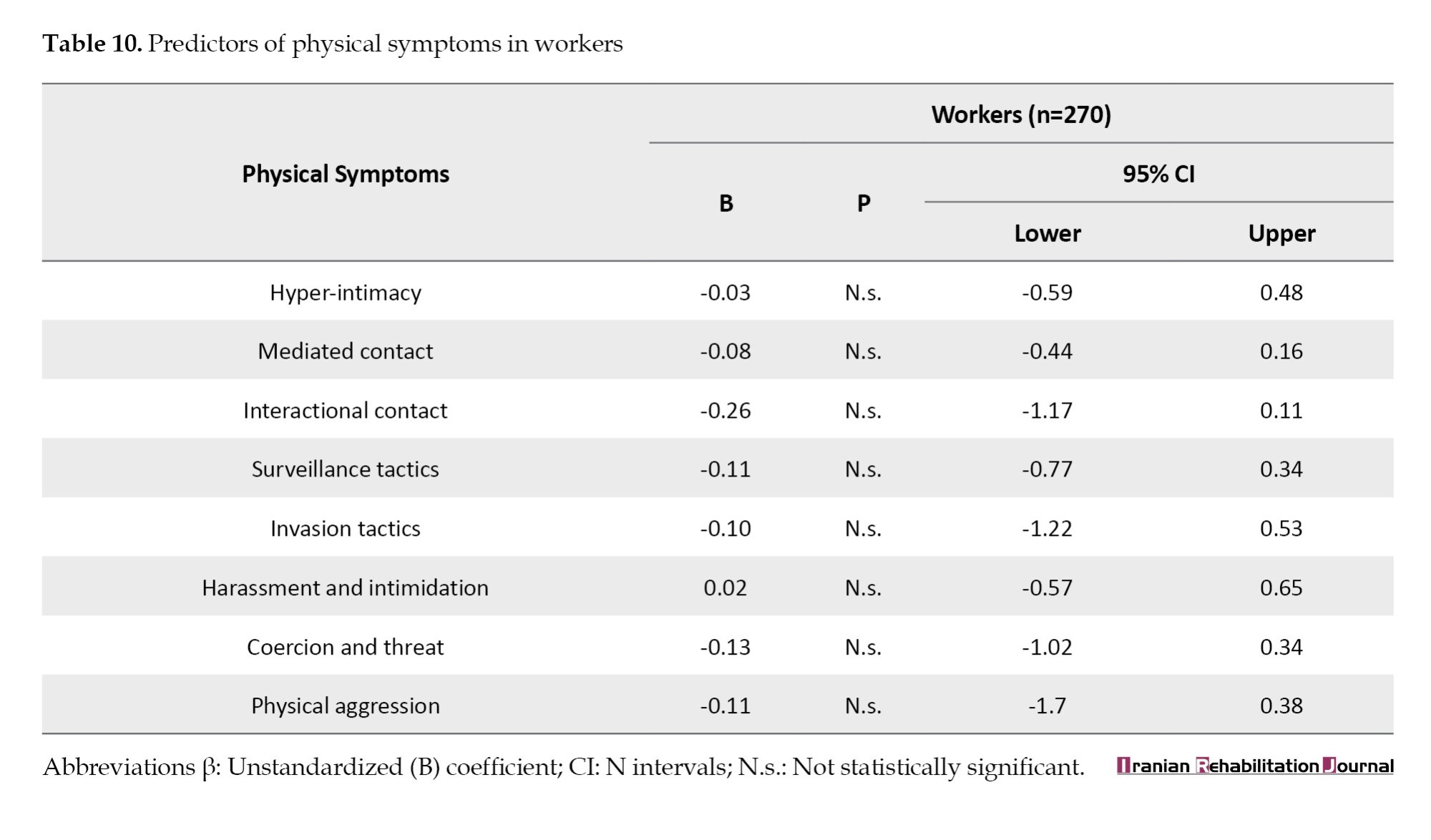

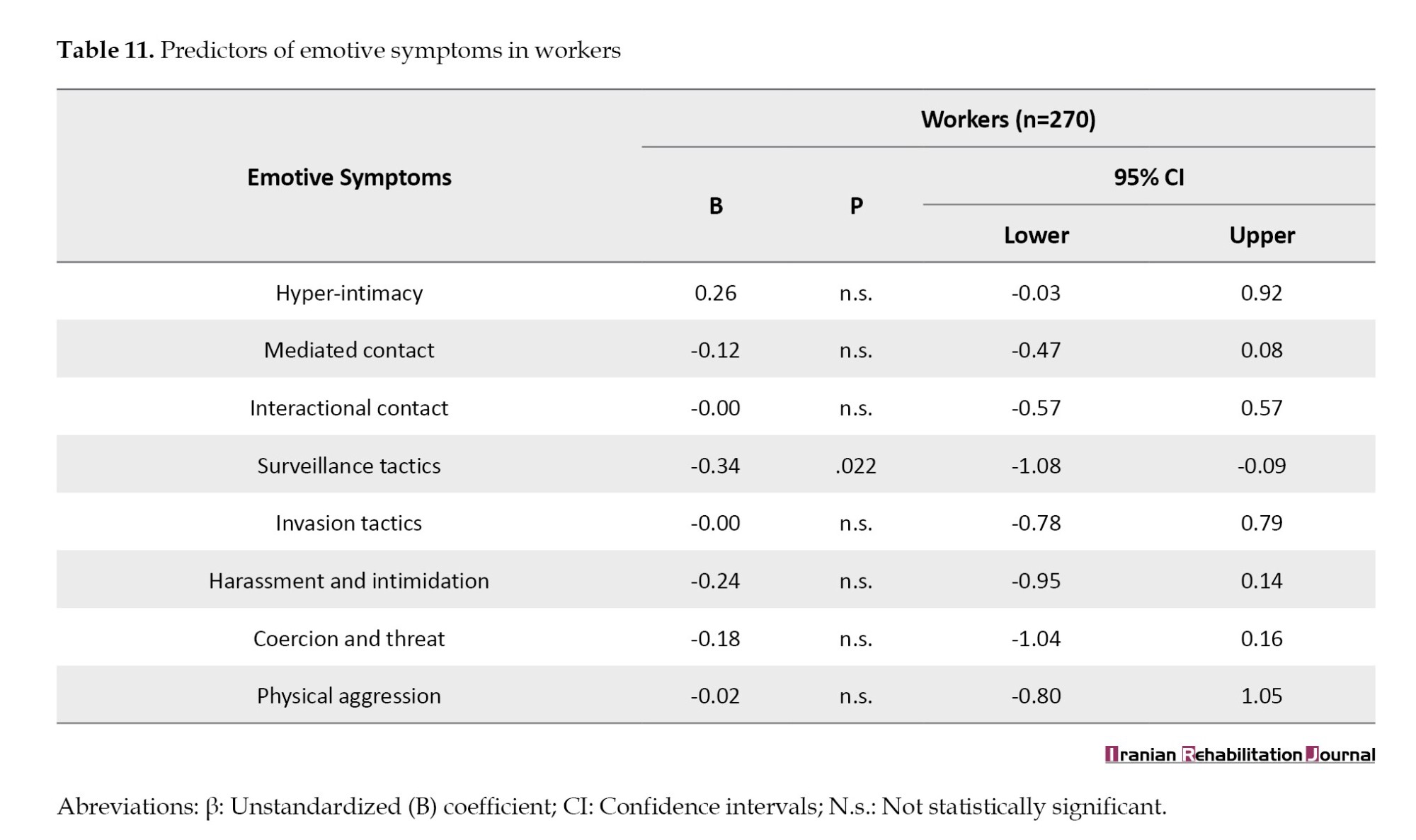

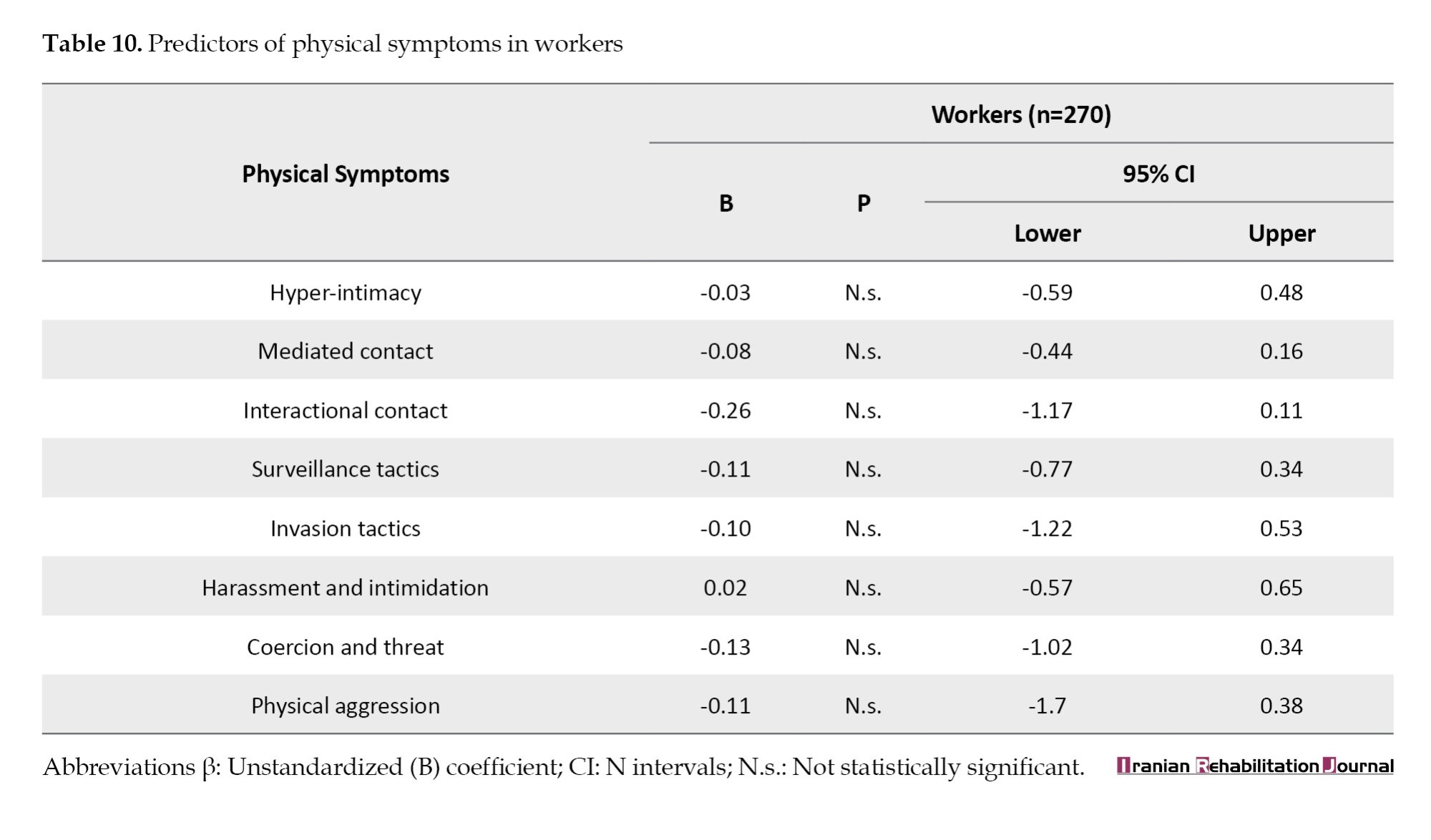

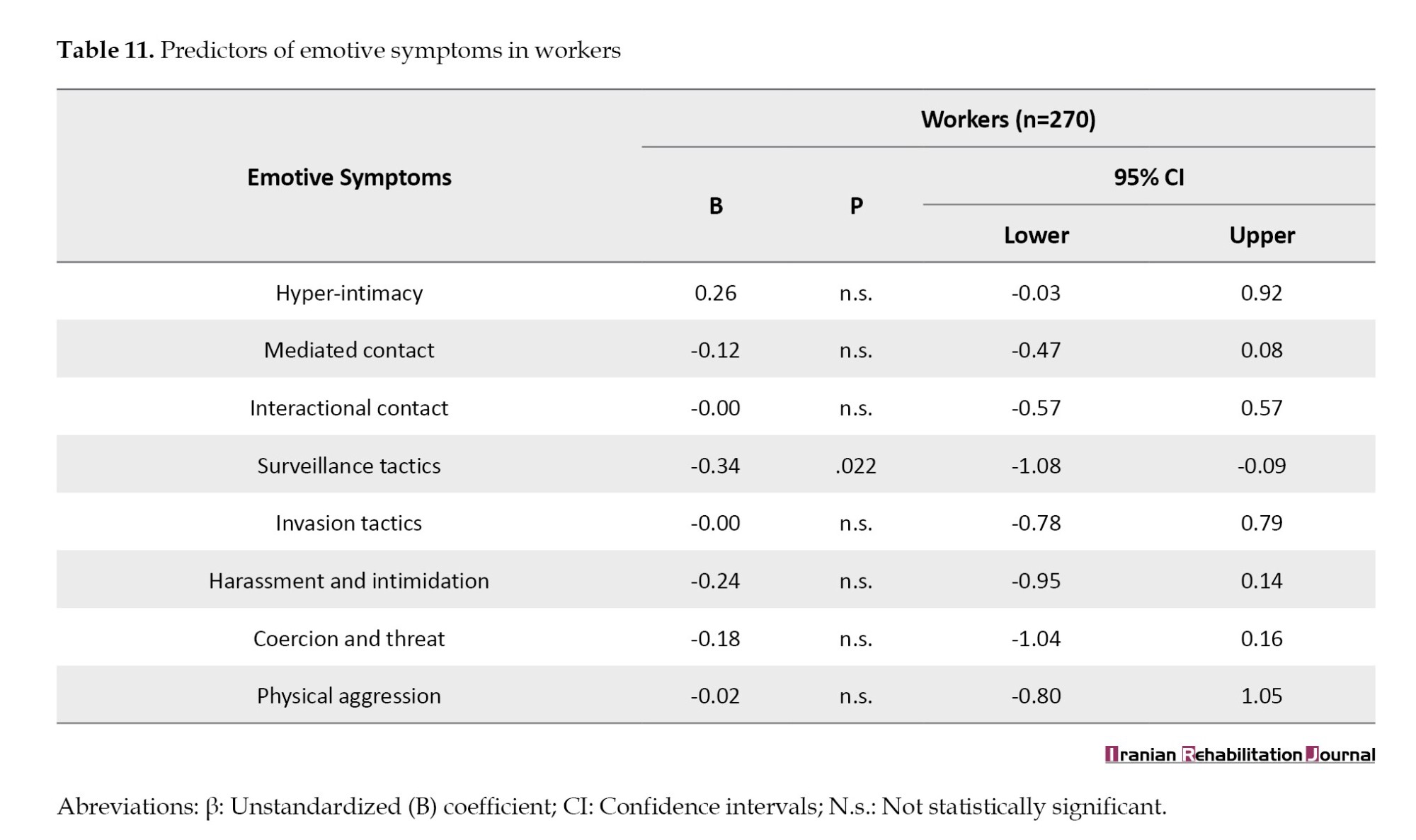

In workers, emotive symptoms were associated with surveillance tactics (Tables 10 and 11).

Discussion

This study compared the victims of stalking in two groups: Students and workers. Analysis of the literature revealed differences in both the experiences of stalking and the consequences of victimization. We made assumptions. The first was that University students were expected to exhibit more behavior than workers. Instead, the hypothesis was not borne out: The behaviors suffered turned out to be the same, with a higher percentage of workers reporting mediated contact, interactive contact, harassment, and physical violence. This is interesting because it is related to the consequences of the phenomenon reported by victims. Students reported more emotional symptoms than workers, with some significantly different symptoms. We talk about suicidal thoughts, sadness, confusion, lack of trust in others, aggressiveness, paranoia, irritability, and agoraphobia. These symptoms indicate a condition that leads to closure on one side and feeds a sense of claustrophobia on the other, so that students are unable to escape the state of victimization [43, 59]. This result is confirmed by the type of physical symptoms that the students report more than the workers, namely loss/increase in appetite, nausea, self-inflicted injuries, hyperarousal, and panic attacks [60]. It is as if the experience is debilitating. Workers reported more sudden anxiety than students. Therefore, hypothesis two is partially confirmed. Other data come from correlations, where negative meanings indicate that as the stalker’s behavior increases, physical and emotional symptoms decrease. A possible explanation could be that the reinforced behavior of the stalker cannot ignore the danger and the need to ask for help; therefore, the subject is forced to take precautions and act [21]. This is our conjecture. Further research could be useful to better understand the dynamics when a subject stalks at different stages of victimization. For example, research using qualitative methods (interviews, focus group discussions) could be used to understand what aspects characterize the decision to defend the victim, ask for help, or activate the home alarm system. Confirming this supposition, inferential statistics showed that interactional contact is associated with physical and emotional symptoms in students, while in workers, the same behavior is associated with emotional symptoms. Interactive contact is the type of behavior that places the victim before the stalker. These behaviors involve third parties, who can then suggest that the victim take precautions. Future research could involve observers of the phenomenon to examine the propensity to help the victim and the type of strategy used, based on the perceived motivations underlying the stalker’s behavior.

Regarding coping strategies, the results do not support our hypothesis that students tend to use more than the workers’ defense strategies (collect evidence, and have a safe plan). The results showed that students were more likely than workers to report increased social contact. This could be related to trying to escape the victim’s isolation [43]. Also, workers were likelier than students to report abusing alcohol and obtaining weapons. This result may be due to the age difference of the subjects because workers are, on average, older than students, and we did not ask how long the stalking behavior lasted. The duration of stalking may determine the perception of danger, especially when other people are involved and not just the stalking victim [11, 27], such as in the case of digital violence [61]. Further research could be conducted to explore the number and type of secondary victims involved in the phenomenon and attempt to correlate the type of coping strategy with the duration of stalking, investigating any effect on bystanders [62, 63].

Similar to any research, this study has limitations. The first relates to the nature of the research. We conducted a cross-sectional study; therefore, the results should not be generalized and can be referred exclusively to the population studied. Further research should consider comparisons with other populations [64-66]. For example, Harris et al.’s [13] data suggest that healthcare workers are at a higher risk of victimization; therefore, a comparison between this population and a population of workers of other types could be suggested. Another limitation is that we did not consider sociodemographic variables. The first variable was sex [64]. The study showed that most of the victims were female, which confirms data from previous investigations on the prevalence of this phenomenon in the population [27, 36, 67, 68]. For example, a comparison between genders could be useful, to better understand which men and women use coping strategies to understand if there are differences. Moreover, a sociodemographic variable that we did not consider was sexual orientation. Studies by Fedina et al. [31] suggest that sexual orientation may be the trigger for some stalking behavior. Another useful difference that has not been explored is the perception of the phenomenon [69]. It should be noted that participants described themselves as stalking victims. We do not know if this is their perception or if they are truly victims. Analysing the characteristics of victims who report the phenomenon to the police could be useful to better assess their propensity to use this type of strategy [70]. In addition, it would help understand the characteristics of stalking behavior that determine the decision to file a complaint. Another useful type of survey is aimed at awareness campaigns about the phenomenon, what scenarios are presented, and how they affect the perception among men and women.

Prevention and policy implications

Despite these limitations, the research we have conducted allows us to guide intervention and prevention strategies. It is essential to emphasize bystanders’ role in this phenomenon [71]. Bystanders can help the victims defend themselves; they can mitigate the negative effects of stalking by offering support and assistance [30, 72]. Most importantly, they can help the victim to escape isolation, which is a main characteristic of the phenomenon, improving individual resilience and perceived social support [73, 78]. Coming out of isolation can help mitigate the negative effects of stalking and understand what strategies can be used to stop the stalker [79]. At the social and political level, educational campaigns for bystanders and not only victims [80-87] could be useful to understand the different scenarios of stalking (for example, not only the affective relationship or the female gender for the victim and the male gender for the stalker) and building a more respectful society [88-91].

Conclusion

This study aimed to compare stalking victimization between students and workers. Based on the results, workers mainly experience stalking behaviours, including mediated contact and physical violence, while students mainly experience emotional and physical problems. This suggests that while the experienced stalking behaviours are more intense in workers, stalking mostly causes psychological harm to students, perhaps due to their age, social environment, or lack of resources. In addition, students use more social contact for coping, perhaps to avoid isolation. Workers, on the other hand, are more likely to use drugs or acquire weapons, perhaps due to a different perception of risk or for age-related reasons. This study also showed a complex relationship between the stalker's actions and the victim's response; the increase in stalking behaviours may coincide with a decrease in symptoms, suggesting a possible point at which the victims decide to protect themselves. Understanding these differences can help develop more effective and targeted support systems for different groups of stalking victims.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research project was approved by the local Ethics Committee of University of Torino, Torino, Italy (Code: N.277326), and all ethical and legal requirements for studies involving human subjects were strictly adhered to. Data were collected by researchers who had previously trained research assistants. The participants received a paper questionnaire, an information letter, and a consent form. The letter explained the purpose of the study, emphasized the voluntary nature of participation, guaranteed anonymity, and explained how the data would be analyzed. Each participant completed an anonymous questionnaire and returned it immediately after the session. Participation was voluntary and unremunerated.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Material preparation, data collection, and analysis: Daniela Acquadro Maran, Antonella Varetto, and Tatiana Begotti; Conceptualization, study design, writing and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

The etymological term stalking goes back to the language of sport hunting. The term “stalking” refers to pursuing prey that moves stealthily [1], a temporally concealed approach and pursuit with the intent to capture and harm. Applied to interpersonal relationships, this definition means that someone who pursues another person does so with threatening or harmful intent [2]. Meloy [3] asserts that stalking is typically described as malicious and harassing over an extended period, in which a person intentionally acts on another person whose safety is threatened. This definition includes two elements: Threats to safety and the repetition of harassment. Many stalking behaviors can be equated to those of a normal courtship, intentional or not. Petherick asserts that the experience of fear for one’s safety and the duration and persistence of the behavior are some discriminatory features that may contribute. The first is caused by the stalker’s inability or unwillingness to accept the reality of the facts, i.e. the victim is not interested in the relationship. The second is specifically related to repeated harassment; it is this act that identifies the difference between stalking and unwanted courting by an ex-partner, a rejected suitor, or a stranger. Two main characteristics of stalking are repetition over time and the unwanted nature of the stalker’s behaviors. Stalking behaviors are described as persistent harassments in which the stalker establishes various forms of surveillance, communication, control, and unwanted contact with another person. These behaviors are perceived as threatening and may affect the victim’s quality of life [4, 5]. Fear emerges as a critical element in many definitions of stalking, although it is controversial given the difficulties in operationalizing it [6, 7]. According to Sheridan et al. [8] these behaviors can be routine and innocuous acts (e.g. offering gifts, making phone calls, sending written messages) or intimidating acts (e.g. stalking, sending threatening messages) that negatively impact the victim’s daily life. Stalking behaviors tend to escalate in frequency and aggressiveness and may be accompanied by other forms of violence, particularly psychological, physical, and sexual threats and aggression [9]. Spitzberg and Cupach [10] identified eight strategies that stalkers use to harass: Hyper-intimacy, mediated contacts, interactional contacts, surveillance, invasion, harassment and intimidation, coercion and threat, and aggression. Hyperintimacy refers to a range of excessive or inappropriate behaviors (e.g. offering gifts) toward victims. Mediated contacts are forms of communication, including those using information-communication technology (e.g. email, cell phone). Interactive contacts include direct contact (e.g. physical approach, showing up at places where the victim usually is) or indirect contact (e.g. approaching people known to the victim). Surveillance strategies involve monitoring and attempting to obtain information about victims. Invasion tactics include invading and violating the victim’s privacy (e.g. property invasion, theft). Harassment and intimidation are a series of verbal or nonverbal threats designed to upset the victim (e.g. spreading rumors). Coercion and threats consist of behaviors intended to cause harm to the victim (e.g. threats against the victim’s life or that of third parties). Finally, aggression includes intentional acts that cause harm to the victim or third parties (e.g. physical or sexual violence) [11].

Prevalence of the phenomenon

The National Violence Against Women Survey, a representative study in the United States of experiences of violence, including stalking, reports that 8% of women and 2% of men have been stalked at some point in their lives [12]. A meta-analysis of 175 studies on stalking found lifetime prevalence rates for male victims ranging from 2% to 13% and for female victims ranging from 8% to 32% [13]. A particular group of workers were involved in studies on the phenomenon, suggesting that stalking in the workplace is not uncommon. Pathé and Mullen’s [14] study of 100 stalking victims found that 25% first met their stalker at work. Purcell et al. [15] studied 40 female stalkers and found that 58% targeted professional contacts or others they first met at work. In their study of 371 stalking victims in the United Kingdom, Sheridan et al. [16] found that 16% of victims reported that stalkers were in the workplace. Moreover, there is evidence in the literature from surveys of journalists, teachers, politicians, trade :union:ists, university professors, health care professionals, and others. For example, a survey of 493 German journalists showed that the frequency of the phenomenon related to professional activity is 2.19% [17], while the percentage among 721 English teachers is 5.10% [8, 10]. Morgan and Kavanaugh’s [18] study showed that of 934 US university teachers, 33% were stalking victims. A survey conducted by Galeazzi et al. [19] in Italy of 361 healthcare professionals found that the percentage of victimization was 11%, with stalkers being patients in 90% of cases. In their systematic review, Harris et al. [13] found that the prevalence of victimization among mental health professionals varied between 10.2% and 50%.

University students are considered the most vulnerable population to stalking and have higher prevalence rates than the general population [20]. Sheridan et al. [8], reported an average frequency of victimization of 24%, similar to that found in an Italian sample [21]. The prevalence rates range from 8-25% for women and 2-13.3% for men. In a systematic review by Pires, et al. [22], prevalence indicators for lifetime victimization among students varied from 12% [23] to 96% [24]. The prevalence indicator for victimization since the beginning of college was 19.9% [25]. Fisher et al. [26] found a prevalence of 15% of students who were victims of stalking, using the last year as the reference period. Finally, Jordan et al. [27]. used three reference periods for stalking victimization in their study: 40.4% of stalking victimization occurred over a lifetime, 18% of victimization occurred since the student entered college, and 11.3% of victimization occurred in the past year. Data on the prevalence of cyberstalking in the college population only consider the reference period of lifetime victimization, ranging from 13% [28] to 74.8% [29]. Authors, such as Menard et al. [30] and Fedina et al. [31] argue that stalking may develop since this population is mostly young adults and singles who have a desire for independence and predictable routines on university campuses [32].

Consequences of the victimization

Several studies that addressed the impact of stalking on victims reported that mental health was most affected (e.g. anxiety, depressed mood, anger) [33-35]. In addition to mental health, physical consequences (e.g. sleep disturbances, headaches, and muscle weakness) were reported [5, 36, 37]. Fissel et al. [38] also indicated consequences for the victim’s lifestyle (e.g. losing confidence in others). For students, consequences affected different areas: Economic (e.g. changing cell phone number or residence, investing in software to protect technology), social (e.g. social isolation), professional/academic performance (e.g. absence from work or classes, changing or quitting jobs, leaving the University) [39], and the victim’s mental health (e.g. feeling threatened for safety, anger, anxiety, fear) [31]. Paullet et al. [28] also pointed to physical health (e.g. sleep disturbances, fatigue, and headaches) as one of the most affected areas [40].

Coping strategies

Victims most frequently activated sources of informal support (i.e. family and friends) [41-43]. At the same time, studies reported that victims did not report these behaviors to formal sources of support (i.e. security forces, and health professionals) [44-46]. However, Sheridan et al. [16] showed that workers victims experience specific stalker tactics, such as threats of termination and manipulation of workplace practices to gain contact with the target. Concerning student victimization experiences, studies reported that informal sources of support were most frequently activated by victims [44]. In their study, Cass and Mallicoat [47] found several reasons why students do not formally report their stalking victimization, including a sense of shame, especially among those who had a prior intimate relationship with the stalker, and the belief that stalking is not serious enough to report unless it involves persistent threats or physical incidents. The lack of help-seeking behavior by students regarding stalking masks the actual and perceived prevalence and severity of stalking in this population.

Purpose of the present study

In Italy, an anti-stalking law was added to the Penal Code in 2009 (Art. 612 bis). The law defines the offence as “constant threats or harassment of another person to such an extent that a serious, persistent state of anxiety or fear is created, or that the victims have a well-founded fear for their safety or the safety of relatives or other persons connected to the victims by kinship or emotional ties, or that the victims are forced to change their living habits.” Data from the Eurispes [48] report indicated that approximately 1 in 10 citizens reported having experienced stalking. This phenomenon increased by 1.4% compared to 2020. These results are consistent with those from 2014, when the number of stalking victims was 9.9% [49]. The highest percentage of stalking victims was found in the 18-24 age group (13%), while the percentage in other age groups was around 9%. Victims report experiencing fear, anger, and confusion. A previous survey [50] found that the most common behaviors suffered by victims included direct contact (15.1%), sending messages and emails or phone calls or unwanted gifts (13.5%), and repeatedly asking for dates (13.1%). In 11.9% of cases, they waited outside the home or workplace, and in 9.5% of cases, victims were followed or spied on. In a few cases, the behavior consisted of damaging their belongings or threatening them or other close people. Fifty percent of victims reported defending themselves or waiting for the stalker to stop doing nothing. A total of 17.4% asked friends and relatives to intervene, while almost 2 in 10 victims (18.9%) chose to limit outings, hobbies, and socializing with friends. The strategy of reporting to someone is lower among victims aged 18 and 24, who reported it in 9.8% of cases. The older ones are more likely to report (16%) when they are victims of stalking. The 18–24-year-olds are also the ones who most often decide to defend themselves (in 41.5% of the cases): A rather high percentage compared to the other age groups.

Based on the literature and data from the Italian context, this study aims to compare the experience of victimization between students and workers. Therefore, the following objectives were formulated.

To identify behaviors that characterize stalking, students reported a greater number of behaviors (H1).

To determine the consequences experienced, students reported more and more severe physical and emotional symptoms than workers, including depressive and anxiety symptoms (H2).

To evaluate whether students are more likely to defend themselves than workers (H3).

This study aimed to examine the impact of different stalking behaviors on students and workers regarding physical and emotional symptoms (as we do not have a specific hypothesis on this topic, we analyzed it with an exploratory goal).

Materials and Methods

In this cross-sectional study, the participants were 561 self-identified stalking victims: 291 students (51.9%) and 270 workers (48.1%). Most were women (79.9%), and four did not indicate gender. The Mean±SD age of the participants was 29.26±10.37 years; range 18-70 years. Regarding marital status, most participants were single (39.6%), 29.2% were engaged, 12.8% were married, 7.8% lived in a partnership, 5.2% were divorced, and one person was widowed. 24 participants did not respond to this question. Two groups of victims of stalking were identified: Those who identified themselves as students and those who identified themselves as workers.

Measures

To measure behaviors that characterize the stalking experience, a modified Italian version of the network for surviving stalking questionnaire was used [51, 52]. The items included behaviors, such as unusual letters, phone calls, emails, harassment, threats, and physical assault (28 items, possible answer options: No=0; once a month=1; more than once a month=2; once a week=3; more than once a week=4; daily=5). As suggested by Spitzberg and Cupach [53], these behaviors were classified as follows:

1) Hyper-intimacy (four items: Offering gifts, sending unwanted material, unwarranted expressions of affection, and attempts to ingratiate themselves with the stalking target; range=0-20); 2) Mediated contact (four items: Letter, email, text message, social contact; range=0-20); 3) Interactional Contact (three items: Physical approach, showing up at home and university/workplace, approaching friends/colleagues/relatives; range=0-15); 4) Surveillance (three items: Following, photos, and moving around); 5) Invasion (three items: Visiting home, visiting workplace/university, property invasion; range=0-15); 6) Harassment and Intimidation (three items: Spreading rumours, harassment of the victim, and harassment of friends/colleagues/relatives; range=0-15); 7) Coercion and Threat (four items: Coercion, threats against the life of the victim, threats against the life of friends/colleagues/relatives, threats against the life of the victim’s pet; range=0-20), and 8) Aggression (four items: Physical violence, sexual violence, property damage, violence against the victim’s pet; range=0-20).

23 items from the Italian version of the stalking questionnaire were used to measure the consequences of the experience [54]. Twelve items examined physical symptoms (e.g. headaches, sleep disturbances, nausea, panic attacks; possible response options: Yes/no) and 10 items examined emotional symptoms (e.g. anger, fear, aggressiveness; possible response options: Yes/no).

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Italian short version of the Beck depression inventory (BDI) [55, 56]. It includes 13 items to classify symptoms and define different severity levels: No or minimal depression (scores 0–4), mild depression (5–7), moderate depression (8–15), and severe depression (>15) (in this study, Cronbach’s α was 0.92, indicating excellent internal consistency).

The state-trait anxiety inventory (STAI) was used to measure anxiety symptoms [57, 58]. It includes two subscales (STAI-Y1 and STAI-Y2; 20 items each) that assess how participants feel in the present moment (state anxiety) and how they feel most of the time (trait anxiety). The total scores ranged from 20 to 80, with 40 being the threshold for anxiety symptoms. The rating scale had different severity levels: Mild (40-50), moderate (51-60), and severe (>60). This study’s Cronbach’s α values were 0.91 for both subscales, indicating excellent internal consistency.

Coping strategies were measured using eight items from the Italian version of the stalking questionnaire [54]. The different coping strategies included collecting evidence, preparing a safety plan, increasing social contacts, increasing alcohol misuse, increasing drug misuse, increasing psychotropic substance use, decreasing social contacts, and getting a weapon (possible response options: Yes or no).

Procedure

All ethical guidelines were followed, including the legal requirements for research involving human subjects. Data were collected by research assistants whom the researchers had previously trained. Participants completed an anonymous questionnaire, which was given individually in paper form, and returned immediately after collection. They received an information letter, an informed consent form, and a questionnaire. The letter clearly explained the research objectives, voluntary nature of participation, data anonymity, and the results. The questionnaire took approximately 20 minutes to complete. All respondents participated in the study voluntarily and received no compensation.

Data analysis

SPSS software, version 29 was used to generate descriptive and inferential statistics. Descriptive measures (Mean±SD) were calculated for all test variables for the two groups of participants (students and workers) and their stalking experiences. χ2-tests were used to measure differences between stalking victims (students and workers) on episode characteristics (physical and emotional symptoms, severity of depression, and anxiety symptoms). Differences in stalking behavior, consequences of victimization (depression, state, and trait anxiety scores), and coping strategies were examined using descriptive statistics. Differences in scores were examined using the t-test. Differences were considered statistically significant when P<0.05. Correlations were calculated to examine the relationships between stalking behavior and physical and emotional symptoms, including depressive and anxiety symptoms. Simple linear regression was used to analyze which variables were the best predictors of anxiety and depression symptoms among victims. We summed the physical and emotional scores to perform the analyses and calculated the means to create dummy variables. Physical and emotional scores were considered dependent variables, and stalking behavior and physical and emotional symptoms were used as independent variables. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

Sociodemographic analysis

The results of the descriptive statistics showed that in the group of students, 79% are women. The students had an Mean±SD, 22.52±2.63. Most were single (55.3%), 37% were engaged, 3.9% lived in a partnership, 1.8% were married, and one was divorced. In the group of workers, the percentage of women is 82% (χ2=0.36, P=0.212). The workers have a mean age of 36.87±10.59; t=-20.77, P=0.001). Most were married (26.5%), 25.7% were single, 23.3% were engaged, 13% were in a partnership, 11.1% were divorced, and one was widowed.

Behaviors characterizing stalking

As shown in Table 1, workers were more likely to indicate certain behaviours than students. These behaviours are mediated contact, interactional contact harassment, and intimidation.

Physical and emotional symptoms

On average, students indicated 2.1±2.37 and workers indicated 1.86±2.13 physical symptoms (t=1.26; P=0.208; Cohen’s d=-0.063). Students are more prone to indicate some physical symptoms (loss/increase in appetite, nausea, self-inflicted injuries, and panic attacks) than are workers. Regarding emotive symptoms, students on average indicate 3.92±2.47 and workers indicate 2.83±1.99 symptoms (t=5.52; P=0.001; Cohen’s d=0.484). Students scored higher on most emotional symptoms (suicidal thoughts, sadness, confusion, lack of confidence in others, aggressiveness, paranoia, irritation, and agoraphobia) (Table 2).

Regarding the symptoms of depression and anxiety, the results showed that on average, workers indicated a higher score for state anxiety (Table 3).

Specifically, the evaluation of scores for depressive symptoms and anxiety showed no differences between students and workers. It should be noted that the rating of depression is at a minimal level, while for anxiety, the condition that is suddenly most pronounced is mild anxiety symptoms (Table 4).

Coping strategies

Analysis of the results for coping strategies revealed some differences in students’ and workers’ strategies. Students were more likely than workers to indicate an increase in social contact. In contrast, workers were more likely than students to indicate an increase in alcohol misuse and the strategy of getting a weapon (Table 5).

Inferential statistics

A correlation matrix was used to examine the relationships between stalking behaviors, physical and emotional symptoms, BDI, STAI from Y1, and STAI from Y2 in student and worker victims of stalking (Tables 6 and 7).

In students, the results show that as hyper-intimacy, interactional contact, surveillance tactics, harassment, and intimidation behaviors increase, emotional symptoms decrease, while physical symptoms decrease as interactional contact, harassment, intimidation, coercion, and threat behaviors increase. In workers, physical symptoms decrease as hyper-intimacy, interactional contact, surveillance tactics, harassment and intimidation, invasion tactics, and coercion, and threat behaviors increase, and emotional symptoms decrease as interactional contact, surveillance tactics, harassment and intimidation, invasion tactics, coercion, and threat behaviors increase. The only exception is trait anxiety, whose symptoms increase in workers as interactional contact, coercion, and threats increase.

Linear regression

A linear regression analysis was conducted to predict the risk of physical and emotional symptoms in the victims (students and workers). Physical and emotional symptoms were divided into two categories (suffering: Yes/no) using the cut-off based on mean scores (students’ physical symptoms=2.11, emotional symptoms=3.92; workers’ physical symptoms=1.86, emotional symptoms=2.83).

The results showed that students’ physical symptoms were associated with interactional contact and coercion threats (Table 8).

Emotional symptoms were associated with interactional contact (Table 9).

In workers, emotive symptoms were associated with surveillance tactics (Tables 10 and 11).

Discussion

This study compared the victims of stalking in two groups: Students and workers. Analysis of the literature revealed differences in both the experiences of stalking and the consequences of victimization. We made assumptions. The first was that University students were expected to exhibit more behavior than workers. Instead, the hypothesis was not borne out: The behaviors suffered turned out to be the same, with a higher percentage of workers reporting mediated contact, interactive contact, harassment, and physical violence. This is interesting because it is related to the consequences of the phenomenon reported by victims. Students reported more emotional symptoms than workers, with some significantly different symptoms. We talk about suicidal thoughts, sadness, confusion, lack of trust in others, aggressiveness, paranoia, irritability, and agoraphobia. These symptoms indicate a condition that leads to closure on one side and feeds a sense of claustrophobia on the other, so that students are unable to escape the state of victimization [43, 59]. This result is confirmed by the type of physical symptoms that the students report more than the workers, namely loss/increase in appetite, nausea, self-inflicted injuries, hyperarousal, and panic attacks [60]. It is as if the experience is debilitating. Workers reported more sudden anxiety than students. Therefore, hypothesis two is partially confirmed. Other data come from correlations, where negative meanings indicate that as the stalker’s behavior increases, physical and emotional symptoms decrease. A possible explanation could be that the reinforced behavior of the stalker cannot ignore the danger and the need to ask for help; therefore, the subject is forced to take precautions and act [21]. This is our conjecture. Further research could be useful to better understand the dynamics when a subject stalks at different stages of victimization. For example, research using qualitative methods (interviews, focus group discussions) could be used to understand what aspects characterize the decision to defend the victim, ask for help, or activate the home alarm system. Confirming this supposition, inferential statistics showed that interactional contact is associated with physical and emotional symptoms in students, while in workers, the same behavior is associated with emotional symptoms. Interactive contact is the type of behavior that places the victim before the stalker. These behaviors involve third parties, who can then suggest that the victim take precautions. Future research could involve observers of the phenomenon to examine the propensity to help the victim and the type of strategy used, based on the perceived motivations underlying the stalker’s behavior.

Regarding coping strategies, the results do not support our hypothesis that students tend to use more than the workers’ defense strategies (collect evidence, and have a safe plan). The results showed that students were more likely than workers to report increased social contact. This could be related to trying to escape the victim’s isolation [43]. Also, workers were likelier than students to report abusing alcohol and obtaining weapons. This result may be due to the age difference of the subjects because workers are, on average, older than students, and we did not ask how long the stalking behavior lasted. The duration of stalking may determine the perception of danger, especially when other people are involved and not just the stalking victim [11, 27], such as in the case of digital violence [61]. Further research could be conducted to explore the number and type of secondary victims involved in the phenomenon and attempt to correlate the type of coping strategy with the duration of stalking, investigating any effect on bystanders [62, 63].

Similar to any research, this study has limitations. The first relates to the nature of the research. We conducted a cross-sectional study; therefore, the results should not be generalized and can be referred exclusively to the population studied. Further research should consider comparisons with other populations [64-66]. For example, Harris et al.’s [13] data suggest that healthcare workers are at a higher risk of victimization; therefore, a comparison between this population and a population of workers of other types could be suggested. Another limitation is that we did not consider sociodemographic variables. The first variable was sex [64]. The study showed that most of the victims were female, which confirms data from previous investigations on the prevalence of this phenomenon in the population [27, 36, 67, 68]. For example, a comparison between genders could be useful, to better understand which men and women use coping strategies to understand if there are differences. Moreover, a sociodemographic variable that we did not consider was sexual orientation. Studies by Fedina et al. [31] suggest that sexual orientation may be the trigger for some stalking behavior. Another useful difference that has not been explored is the perception of the phenomenon [69]. It should be noted that participants described themselves as stalking victims. We do not know if this is their perception or if they are truly victims. Analysing the characteristics of victims who report the phenomenon to the police could be useful to better assess their propensity to use this type of strategy [70]. In addition, it would help understand the characteristics of stalking behavior that determine the decision to file a complaint. Another useful type of survey is aimed at awareness campaigns about the phenomenon, what scenarios are presented, and how they affect the perception among men and women.

Prevention and policy implications

Despite these limitations, the research we have conducted allows us to guide intervention and prevention strategies. It is essential to emphasize bystanders’ role in this phenomenon [71]. Bystanders can help the victims defend themselves; they can mitigate the negative effects of stalking by offering support and assistance [30, 72]. Most importantly, they can help the victim to escape isolation, which is a main characteristic of the phenomenon, improving individual resilience and perceived social support [73, 78]. Coming out of isolation can help mitigate the negative effects of stalking and understand what strategies can be used to stop the stalker [79]. At the social and political level, educational campaigns for bystanders and not only victims [80-87] could be useful to understand the different scenarios of stalking (for example, not only the affective relationship or the female gender for the victim and the male gender for the stalker) and building a more respectful society [88-91].

Conclusion

This study aimed to compare stalking victimization between students and workers. Based on the results, workers mainly experience stalking behaviours, including mediated contact and physical violence, while students mainly experience emotional and physical problems. This suggests that while the experienced stalking behaviours are more intense in workers, stalking mostly causes psychological harm to students, perhaps due to their age, social environment, or lack of resources. In addition, students use more social contact for coping, perhaps to avoid isolation. Workers, on the other hand, are more likely to use drugs or acquire weapons, perhaps due to a different perception of risk or for age-related reasons. This study also showed a complex relationship between the stalker's actions and the victim's response; the increase in stalking behaviours may coincide with a decrease in symptoms, suggesting a possible point at which the victims decide to protect themselves. Understanding these differences can help develop more effective and targeted support systems for different groups of stalking victims.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research project was approved by the local Ethics Committee of University of Torino, Torino, Italy (Code: N.277326), and all ethical and legal requirements for studies involving human subjects were strictly adhered to. Data were collected by researchers who had previously trained research assistants. The participants received a paper questionnaire, an information letter, and a consent form. The letter explained the purpose of the study, emphasized the voluntary nature of participation, guaranteed anonymity, and explained how the data would be analyzed. Each participant completed an anonymous questionnaire and returned it immediately after the session. Participation was voluntary and unremunerated.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Material preparation, data collection, and analysis: Daniela Acquadro Maran, Antonella Varetto, and Tatiana Begotti; Conceptualization, study design, writing and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Goldsworthy T, Raj M. Stopping the Stalker: Victim responses to Stalking An examination of victim responses to determine factors affecting the intensity and duration of stalking. Griffith Journal of Law & Human Dignity. 2014; 2(1). [DOI:10.69970/gjlhd.v2i1.575]

- Bendlin M, Sheridan L. Risk Factors for severe violence in intimate partner stalking situations: An analysis of police records. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2021; 36(17-18):7895-916. [DOI:10.1177/08862605198477] [PMID]

- Meloy JR. Stalking. An old behavior, a new crime. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1999; 22(1):85-99. [DOI:10.1016/S0193-953X(05)70061-7] [PMID]

- Spitzberg BH. Acknowledgment of unwanted pursuit, threats, assault, and stalking in a college population. Psychology of Violence. 2017; 7(2):265. [DOI:10.1037/a0040205]

- Logan TK. Examining stalking experiences and outcomes for men and women stalked by (ex) partners and non-partners. Journal of Family Violence. 2020; 35(7):729-39. [DOI:10.1007/s10896-019-00111-w]

- Owens JG. Why Definitions Matter: Stalking Victimization in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2016; 31(12):2196-226. [DOI:10.1177/0886260515573577] [PMID]

- Gatewood Owens J. A gender-biased definition: Unintended impacts of the fear requirement in stalking victimization. Crime & Delinquency. 2017; 63(11):1339-62. [DOI:10.1177/00111287156158]

- Sheridan LP, Blaauw E, Davies GM. Stalking: Knowns and unknowns. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2003; 4(2):148-62. [DOI:10.1177/1524838002250766] [PMID]

- Quinn-Evans L, Keatley DA, Arntfield M, Sheridan L. A behavior sequence analysis of victims' accounts of stalking behaviors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2021; 36(15-16):6979-97. [DOI:10.1177/0886260519831389] [PMID]

- Spitzberg BH, Cupach WR. The state of the art of stalking: Taking stock of the emerging literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2007; 12(1):64-86. [DOI:10.1016/j.avb.2006.05.001]

- Randa R, Reyns BW, Fansher A. Victim reactions to being stalked: Examining the effects of perceived offender characteristics and motivations. Behavioral Sciences & The Law. 2022; 40(5):715-31. [DOI:10.1002/bsl.2599] [PMID]

- Tjaden PG, Thoennes N. Stalking in America: Findings from the national violence against women survey. Washington: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice; 1998. [Link]

- Harris N, Sheridan L, Robertson N. Prevalence and psychosocial impacts of stalking on mental health professionals: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2023; 24(5):3265-79. [DOI:10.1177/15248380221129581] [PMID]

- Pathé M, Mullen PE. The impact of stalkers on their victims. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1997; 170:12-7. [DOI:10.1192/bjp.170.1.12] [PMID]

- Purcell R, Pathé M, Mullen PE. A study of women who stalk. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001; 158(12):2056-60. [DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2056] [PMID]

- Sheridan L, North AC, Scott AJ. Stalking in the workplace. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management. 2019; 6(2):61.[Link]

- Gass P, Martini M, Witthöft M, Bailer J, Dressing H. Prevalence of stalking victimization in journalists: an E-mail survey of German journalists. Violence and Victims. 2009; 24(2):163-71. [DOI:10.1891/0886-6708.24.2.163] [PMID]

- Morgan RK, Kavanaugh KD. Student stalking of faculty: Results of a nationwide survey. College Student Journal. 2011; 45(3):512-24. [Link]

- Galeazzi GM, Elkins K, Curci P. The stalking of mental health professionals by patients. Psychiatric Services. 2005; 56(2):137-8. [DOI:10.1176/appi.ps.56.2.137] [PMID]

- Björklund K, Häkkänen-Nyholm H, Sheridan L, Roberts K. The prevalence of stalking among Finnish university students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010; 25(4):684-98. [DOI:10.1177/0886260509334405] [PMID]

- Acquadro Maran D, Varetto A, Corona I, Tirassa M. Characteristics of the stalking campaign: Consequences and coping strategies for men and women that report their victimization to police. PLoS One. 2020; 15(2):e0229830. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0229830] [PMID]

- Pires SA, Sani AI, Soeiro C. [Stalking e ciberstalking em estudantes universitários: Uma revisão sistemática (Portuguese)]. Journal of Behavioral and Social Research. 2018; 4(2):60-75. [Link]

- McNamara CL, Marsil DF. The prevalence of stalking among college students: the disparity between researcher- and self-identified victimization. Journal of American College Health.2012; 60(2):168-74. [DOI:10.1080/07448481.2011.584335] [PMID]

- Pereira F, Matos M. Cyber-stalking victimization: What predicts fear among Portuguese adolescents? European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research. 2016; 22:253-70. [DOI:10.1007/s10610-015-9285-7]

- Buhi ER, Clayton H, Surrency HH. Stalking victimization among college women and subsequent help-seeking behaviors. Journal of American College Health. 2009; 57(4):419-26. [DOI:10.3200/JACH.57.4.419-426] [PMID]

- Fisher BS, Cullen FT, Turner MG. Being pursued: Stalking victimization in a national study of college women. Criminology & Public Policy. 2002; 1(2):257-308. [DOI:10.1111/j.1745-9133.2002.tb00091.x]

- Jordan CE, Wilcox P, Pritchard AJ. Stalking acknowledgement and reporting among college women experiencing intrusive behaviors: Implications for the emergence of a “classic stalking case”. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2007; 35(5):556-69. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2007.07.008]

- Paullet KL, Rota DR, Swan TT. Cyberstalking: An exploratory study of students at a mid-Atlantic university. Issues in Information Systems. 2009; 10(2):640-9. [Link]

- Marchesini S. [O stalking nos acórdãos da Relação de Portugal: a compreensão do fenómeno antes da tipificação (Portuguese)]. Configurações. Revista Ciências Sociais. 2015; 16:55-74. [DOI:10.4000/configuracoes.2847]

- Ménard KS, Christensen A, Lee DD. The Influence of Offender Motivation on Unwanted Pursuit Perpetration Among College Students. Victims & Offenders. 2023; 1-24. [Link]

- Fedina L, Backes BL, Sulley C, Wood L, Busch-Armendariz N. Prevalence and sociodemographic factors associated with stalking victimization among college students. Journal of American College Health. 2020; 68(6):624-30. [DOI:10.1080/07448481.2019.1583664] [PMID]

- Davis GE, Hines DA, Reed KMP. Routine Activities and Stalking Victimization in Sexual Minority College Students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2022; 37(13-14):NP11242-70. [DOI:10.1177/088626052199187] [PMID]

- Stevens F, Nurse JRC, Arief B. Cyber stalking, cyber harassment, and adult mental health: A systematic review. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking. 2021; 24(6):367-76. [DOI:10.1089/cyber.2020.0253] [PMID]

- Bulut S, Usman C, Nazir T. Stalking of healthcare professionals by their clients: The prevalence, motivation, and effect. Open Journal of Medical Psychology. 2021; 10(2):27-35.[DOI:10.4236/ojmp.2021.102003]

- Fernández Cruz V, Ngo FT. Stalking Victimization and Emotional Consequences: A cross-cultural comparison Between American and Spanish University Students. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2022; 66(6-7):694-717. [DOI:10.1177/0306624X21990816] [PMID]

- Logan TK. Examining stalking assault by victim gender, stalker gender, and victim-stalker relationship. Journal of Family Violence. 2022; 37(1):87-97. [DOI:10.1007/s10896-020-00221-w]

- Matos M, Grangeia H, Ferreira C, Azevedo V, Gonçalves M, Sheridan L. Stalking victimization in Portugal: Prevalence, characteristics, and impact. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice. 2019; 57:103-15. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijlcj.2019.03.005]

- Fissel ER, Reyns BW, Fisher BS. Stalking and cyberstalking victimization research: Taking stock of key conceptual, definitional, prevalence, and theoretical issues. Psycho-criminological approaches to stalking behavior: An International Perspective. 2020; 11-35. [Link]

- Augustyn MB, Rennison CM, Pinchevsky GM, Magnuson AB. Intimate partner stalking among college students: Examining situational contexts related to police notification. Journal of Family Violence. 2020; 35(7):679-91. [Link]

- Zagurny ESF, Compton SD, Dzomeku V, Cannon LM, Omolo T, Munro-Kramer ML. Understanding Stalking Among University Students in Ghana: A mixed-methods study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2022;3 7(15-16):NP13045-66. [PMID]

- Nguyen LK, Spitzberg BH, Lee CM. Coping with obsessive relational intrusion and stalking: the role of social support and coping strategies. Violence and Victims. 2012; 27(3):414-33. [DOI:10.1891/0886-6708.27.3.414] [PMID]

- Podaná Z, Imríšková R. Victims' responses to stalking: An examination of fear levels and coping strategies. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2016; 31(5):792-809.[DOI:10.1177/0886260514556764] [PMID]

- Chan HC, Sheridan L. Coping with stalking and harassment victimization: Exploring the coping approaches of young male and female adults in Hong Kong. Legal and Criminological Psychology. 2020; 25(2):165-81. [Link]

- Villacampa C, Pujols A. Effects of and coping strategies for stalking victimisation in Spain: consequences for its criminalisation. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice. 2019; 56:27-38. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijlcj.2018.11.002]

- Villacampa C, Salat M. Stalking: Victims’ and professionals’ views of legal and institutional treatment. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice. 2019; 59:100345. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijlcj.2019.100345]

- European :union: Agency For Fundamental Rights (FRA). Violence against Women: an EU-wide Survey. Main Results. Schwarzenbergplatz: European :union: Agency For Fundamental Rights; 2015. [Link]

- Cass AI, Mallicoat SL. College student perceptions of victim action: Will targets of stalking report to police? American Journal of Criminal Justice. 2015; 40:250-69. [DOI:10.1007/s12103-014-9252-8]

- Eurispes. I dati sulle vittime di stalking. Rome: Eurispes; 2021.

- The Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (ISTAT). [The number of victims and the forms of violence (Italian)]. Rome:The Istituto Nazionale di Statistica ; 2018. [Link]

- The Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (ISTAT). [Violence against women (Italian)]. Rome:The Istituto Nazionale di Statistica ; 2014. [Link]

- Maran DA, Varetto A, Zedda M. Italian nurses' experience of stalking: A questionnaire survey. Violence and Victims. 2014; 29(1):109-21. [DOI:10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-12-00078] [PMID]

- Acquadro Maran D, Varetto A. Psychological impact of stalking on male and female health care professional victims of stalking and domestic violence. Frontiers in Psychology. 2018; 9:321. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00321] [PMID]

- Spitzberg BH, Cupach WR. The dark side of relationship pursuit: From attraction to obsession and stalking. New York: Routledge; 2014. [DOI:10.4324/9780203805916]

- Miglietta A, Acquadro Maran D. Gender, sexism and the social representation of stalking: what makes the difference?. Psychology of Violence. 2017; 7:563-73. [DOI:10.1037/vio0000070]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961; 4:561-71. [PMID]

- Siligato E, Iuele G, Barbera M, Bruno F, Tordonato G, Mautone A, et al. Freezing effect and bystander effect: Overlaps and differences. Psych. 2024; 6(1):273-87. [DOI:10.3390/psych6010017]

- Spielberger CD. Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory STAI (form Y) (“self-evaluation questionnaire”). Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983.

- Pedrabissi L, Santinello M. Inventario Per l’ansia di «Stato» e di «Tratto»: Nuova Versione Italiana Dello STAI Forma Y: Manuale [State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: The Italian New Version of STAI Y Form]. Firenze, Italy: Organizzazioni Speciali; 1989.

- Schiller D, Yu ANC, Alia-Klein N, Becker S, Cromwell HC, Dolcos F, et al. The human affectome. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2024; 158:105450. [DOI:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2023.105450] [PMID]

- Bruno A, Rizzo A, Muscatello MRA, Celebre L, Silvestri MC, Zoccali RA, Mento C. Hyperarousal scale: Italian cultural validation, age and gender differences in a nonclinical population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(4):1176. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17041176] [PMID]

- Rizzo A, Princiotta E, Iuele G. Exploring the link between smartphone use, recorded violence, and social sharing in 80 case studies in Italy. Psych. 2023; 5(4):1241-55. [Link]

- Barbera M, Rosi N, Grillo C, Yıldırım M, Öztekin GG, Scimone S, et al. Delinquent behaviors in Southern Italy: A survey on adolescents perceptions. Advances in Medicine, Psychology, and Public Health. 2024; 1(4):243-54. [Link]

- Siligato E, Iuele G, Barbera M, Bruno F, Tordonato G, Mautone A, et al. Freezing effect and bystander effect: Overlaps and differences. Psych. 2024; 6(1):273-87. [Link]

- Gharib M, Borhaninejad V, Rashedi V. Mental health challenges among older adults. Advances in Medicine, Psychology, and Public Health. 2024; 1(3):106-7. [Link]

- Minniti D, Presutti M, Alesina M, Brizio A, Gatti P, Maran DA. Antecedents and consequences of work-related and personal bullying: A cross-sectional study in an Italian healthcare facility. Advances in Medicine, Psychology, and Public Health. 2024; 1(4):225-42. [Link]

- Sacco A. Il fenomeno delle aggressioni a danno degli operatori sanitari: Risultati di uno studio “cross sectional” effettuato in una Azienda Sanitaria Locale della Regione Lazio (Italia) [Physical violence against healthcare workers employed at a local health unit in the Lazio Region, Italy: A cross-sectional study]. Giornale Italiano di Psicologia e Medicina del Lavoro. 2022; 2(1):50-6. [Link]

- Chan HCO, Sheridan L. Who are the stalking victims? Exploring the victimization experiences and psychosocial characteristics of young male and female adults in Hong Kong. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2021; 36(21-22):NP11994-2015. [DOI:10.1177/0886260519889] [PMID]

- Hilal M, Khabbache H, Ait Ali D. Dropping out of school: A psychosocial approach. Advances in Medicine, Psychology, and Public Health. 2024; 1(1):26-36. [Link]