Volume 23, Issue 2 (June 2025)

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2025, 23(2): 233-242 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mohammed Khalil I, A Yasir A. Nurses’ Knowledge and Attitudes Regarding Artificial Intelligence Technology in Iraq. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2025; 23 (2) :233-242

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2503-en.html

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2503-en.html

1- Department of Community Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, University of Babylon, Babylon, Iraq.

Full-Text [PDF 752 kb]

(1118 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2395 Views)

Full-Text: (963 Views)

Introduction

Artificial intelligence technology (AIT), a branch of computer science, uses computer systems to mimic the intelligence of healthcare team members. The three primary categories of this technology in the healthcare industry are natural language processing, deep learning, and machine learning. It automates several tasks, including learning and decision-making [1, 2]. Artificial intelligence (AI) can help with disease assessment, diagnosis, and solving various clinical issues in the healthcare industry. It can also reduce data loss, enhance patient safety, reduce nurse workload, enhance inpatient care management, and strengthen nursing communication skills [3]. The way the nursing profession is structured and organized has changed significantly as a result of technological advancements: Nursing is changing as a result of new ways to deliver healthcare in the modern era, including the use of electronic health records and the development of biomedical and engineering technologies that allow for the advancement of progressively sophisticated healthcare, robotic, and AI technologies [4]. AI is rapidly revolutionizing healthcare, and it can potentially revolutionize the nursing profession. According to empirical data, AI already impacts nursing practice, including nursing duties, clinical care, and nurse-patient interaction [5-7]. This study aims to assess nurses’ attitudes and knowledge about AI technology and investigate the relationship between nurses’ knowledge and attitudes regarding AI with socio-demographic variables.

Materials and Methods

The study design and setting

This qualitative cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted to assess nurses’ attitudes and knowledge about AIT using a questionnaire-based assessment approach at Al-Hilla Hospitals in Babylon Governorate from September 25, 2024, to April 1, 2025. The study was conducted at four hospitals in the Babylon Governorate (AL-Imam Sadiq Teaching Hospital, AL-Hilla Teaching Surgical Hospital, Marjan Hospital, and AL-Shomali General Hospital).

Study participants and sampling

A non-probability sampling technique chooses a convenient sample of 354 nurses. The study sample is spread among several hospital departments, such as the emergency room, critical care units, dialysis units, maternal and child units, and medical-surgical wards. Based on the total number of nurses in the four hospitals, 3122, the necessary sample size was 354 nurses, as determined using Slovin’s computation of sample size method (Equation 1):

1. n=N/1+N(e)2=354

n=corrected sample size. The size of the population is denoted by N. According to the study, circumstances at a 95% confidentiality level, e=error margin, and e=0.05.

Data collection and instrument tools

A questionnaire was developed after thoroughly analyzing the literature pertinent to the current investigation. The scale was used with slight modifications to a few items to make it suitable for this study. The questionnaire contains the following: Ι: The sociodemographic data questionnaire (SDVs) includes information, such as “number of training courses, unit/department, years of nursing experience, sex, age, and educational background.” ΙΙ: Nurse’s knowledge scale adapted by Rony et al. and Swed et al. [8, 9]; this section consists of 14 items to assess nurses’ knowledge regarding AI. ΙΙΙ: Nurses’ attitudes scale adapted by Schepman and Rodway [10]. This part consisted of 17 items to assess nurses’ attitudes regarding AI. A three-point Likert scale was used for rating and scoring to assess nurses’ attitudes regarding AI: Disagree, neutral, and agree. A two-point scale was used to rate the items. The items were rated as (yes and no), and the scale levels were scored as (2) for yes and (1) for no. Data were gathered using an adapted and created questionnaire (Arabic translation) to help the participants comprehend the study, following the completion of the necessary approvals. Additionally, the researchers translated all of the tools into Arabic and then back into English to ensure the instrument’s validity, the questionnaire was shown to ten panel members who were experts in the field: Two from the College of Nursing at Baghdad University, two from the Nursing College at Karbala University, two from the Nursing College at Kufa University, and two from the Nursing College at Babylon University. The experts revised the tools for their substance, clarity, simplicity, relevance, completeness, and applicability. They provided input, and minor adjustments were made. According to experts, the instruments were valid. Cronbach α was employed as a statistical tool to determine the questionnaire’s reliability; the result was 0.860 for the knowledge scale, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.880 for the attitude scale, indicating that the items’ high reliability and consistently capture the intended construct.

Data analysis

The researcher utilized the SPSS software, version 23 to perform a thorough statistical analysis of the data collected from the study sample and produced insightful findings through a series of exacting statistical tests (e.g. percentage, mean, frequency, Cronbach’s α, Kruskal-Wallis H test, the Mann-Whitney U analysis, the Pearson’s correlation coefficient), which were used to methodically examine the data, determine correlations between variables, and eventually produce the research’s definitive conclusions.

Results

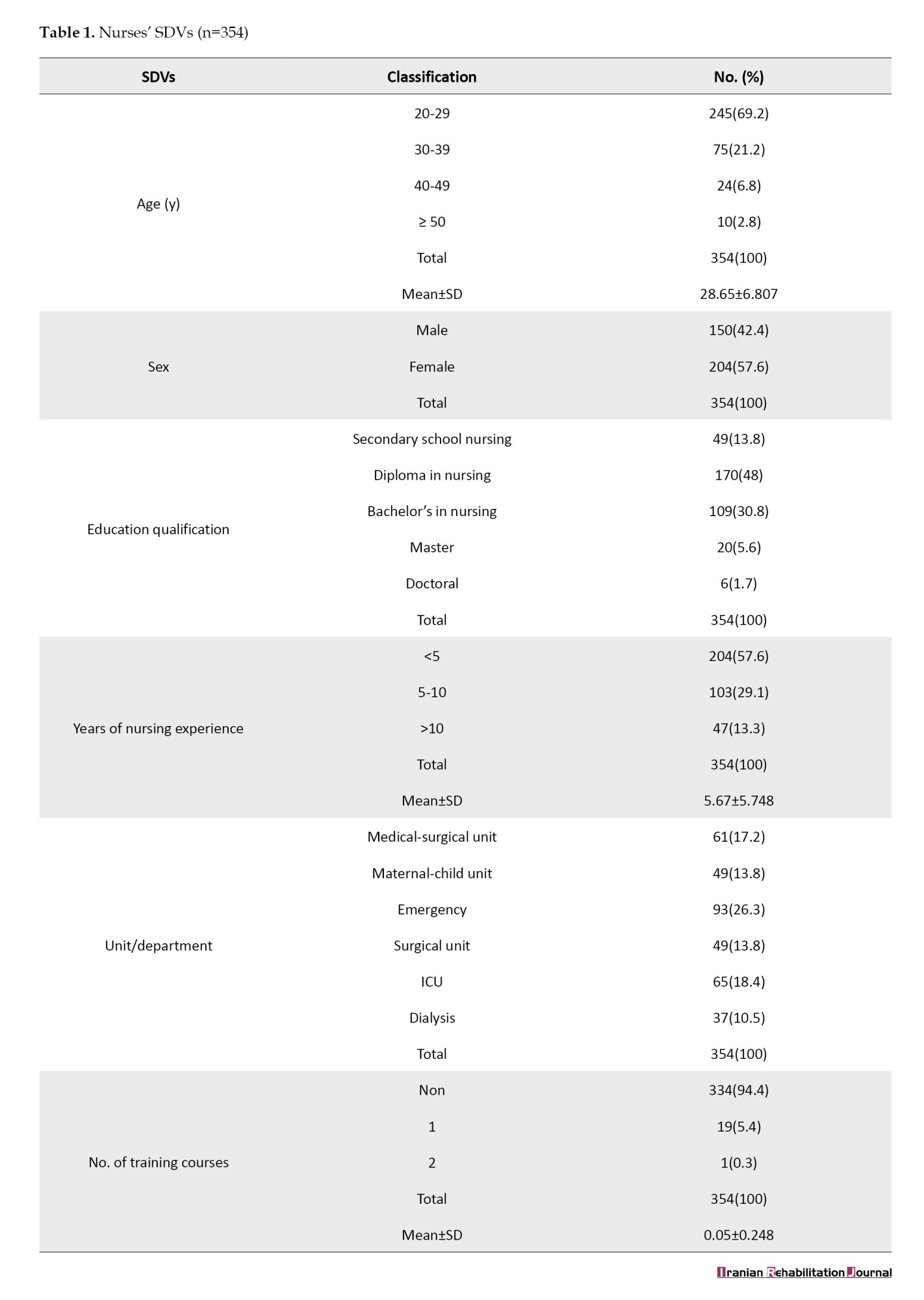

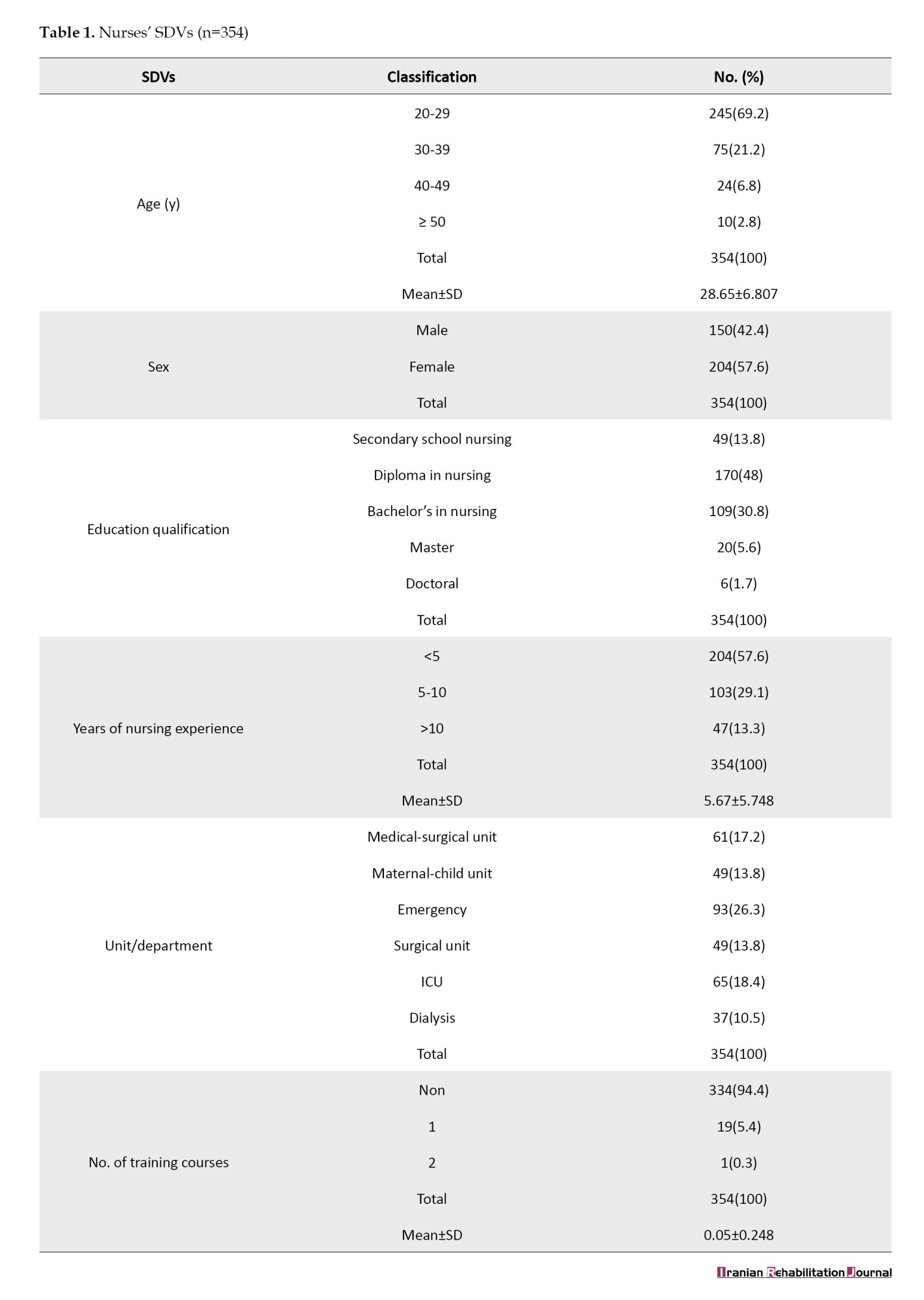

Table 1 presents the distribution of the nurse samples based on their SDVs. The ages of the nurses ranged from 20 to over 50 years, with the majority (69.2%) being in the 20-29 age group, followed by 21.2% in the 30-39 age group. The Mean±SD age of the participants was 28.65±6.807 years. Regarding sex, 57.6% of the nurses were female, and 42.4% were male. Educational qualifications varied, with 48% holding a diploma in nursing, 30.8% having a bachelor’s degree, and smaller percentages holding secondary school nursing qualifications, a master’s, or a doctoral degree. Years of nursing experience show that 57.6% have less than 5 years of experience, with a Mean±SD experience of 5.67±5.748. The nurses were distributed across various units, with the highest percentage (26.3%) in the emergency unit and the lowest in dialysis (10.5%). Regarding training courses, a large majority (94.4%) did not attend any additional courses, with only 5.4% attending one course, and 0.3% attending two courses. The Mean±SD number of training courses attended was 0.05±0.248.

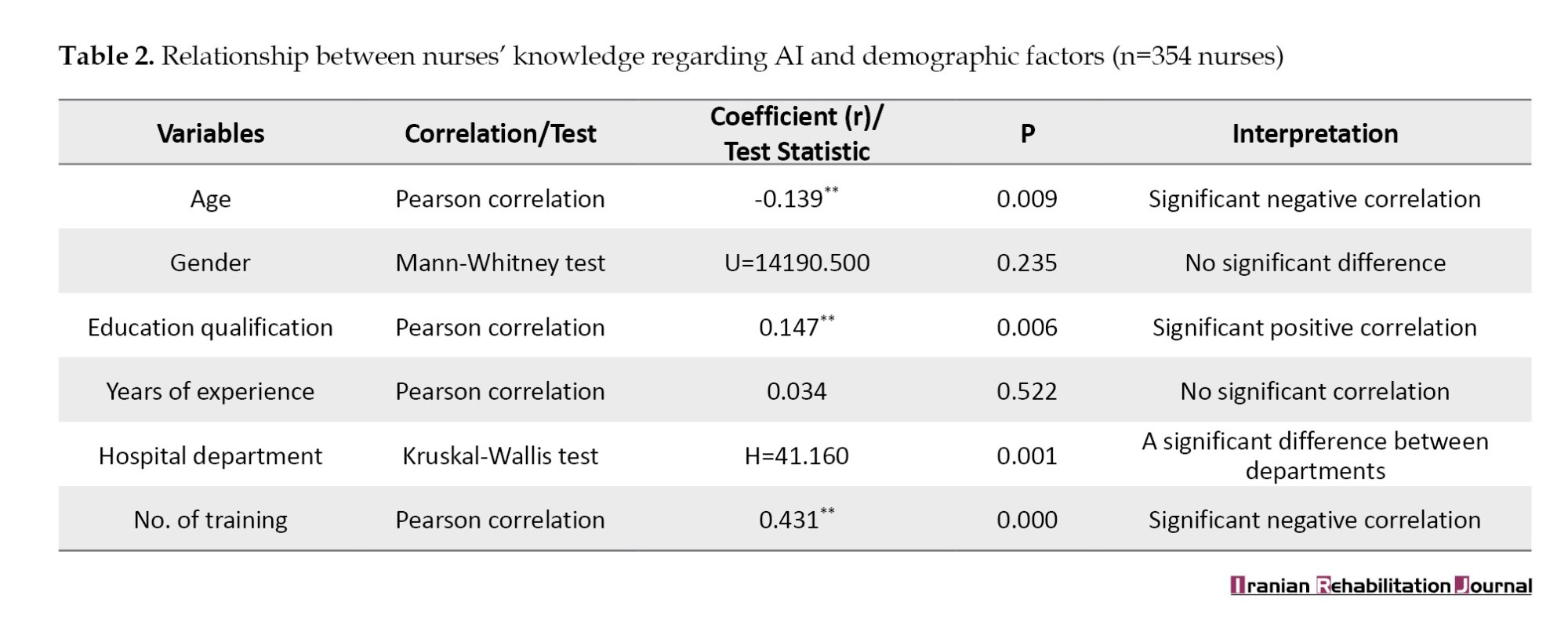

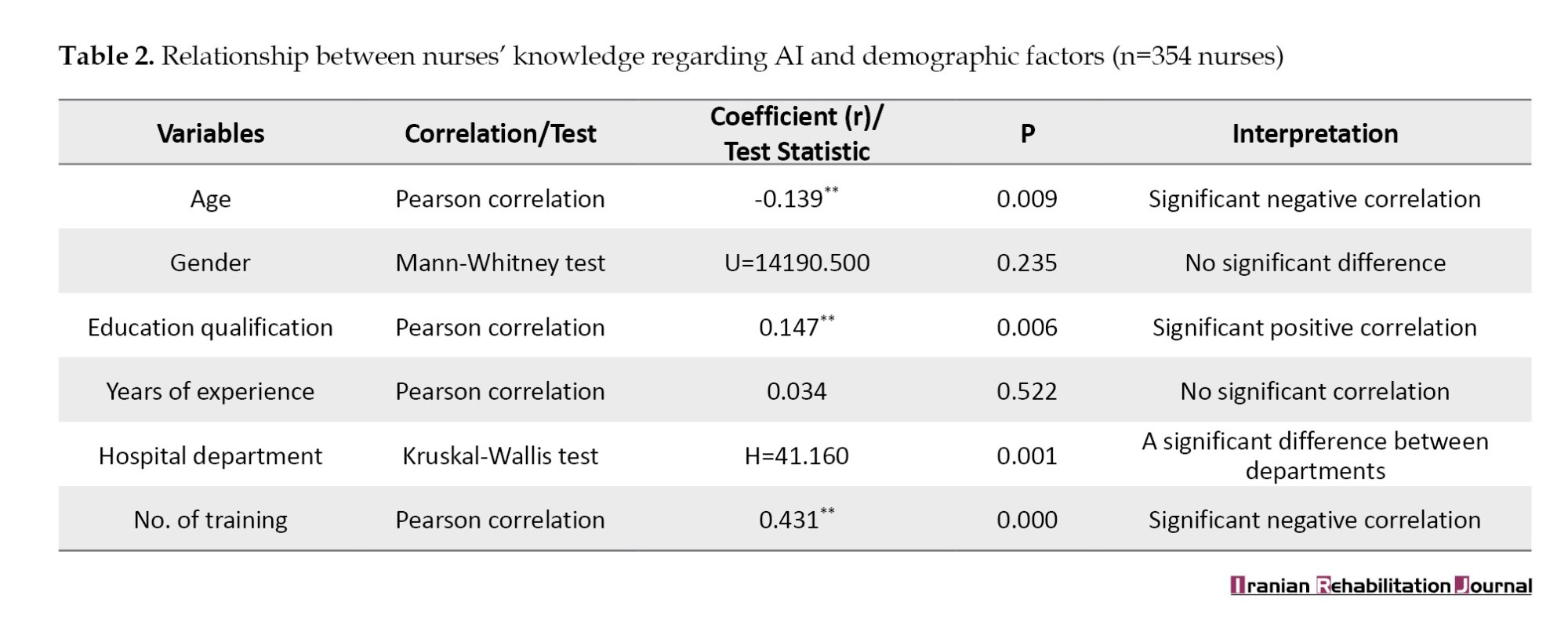

Table 2 presents a substantial association between nurses’ knowledge of AI and their sociodemographic variables (SDVs) regarding age (r=-0.139, P=0.009), educational qualification (r=0.147, P=0.006), departments (P=0.001), and number of training courses (r=0.413, P=0.000).

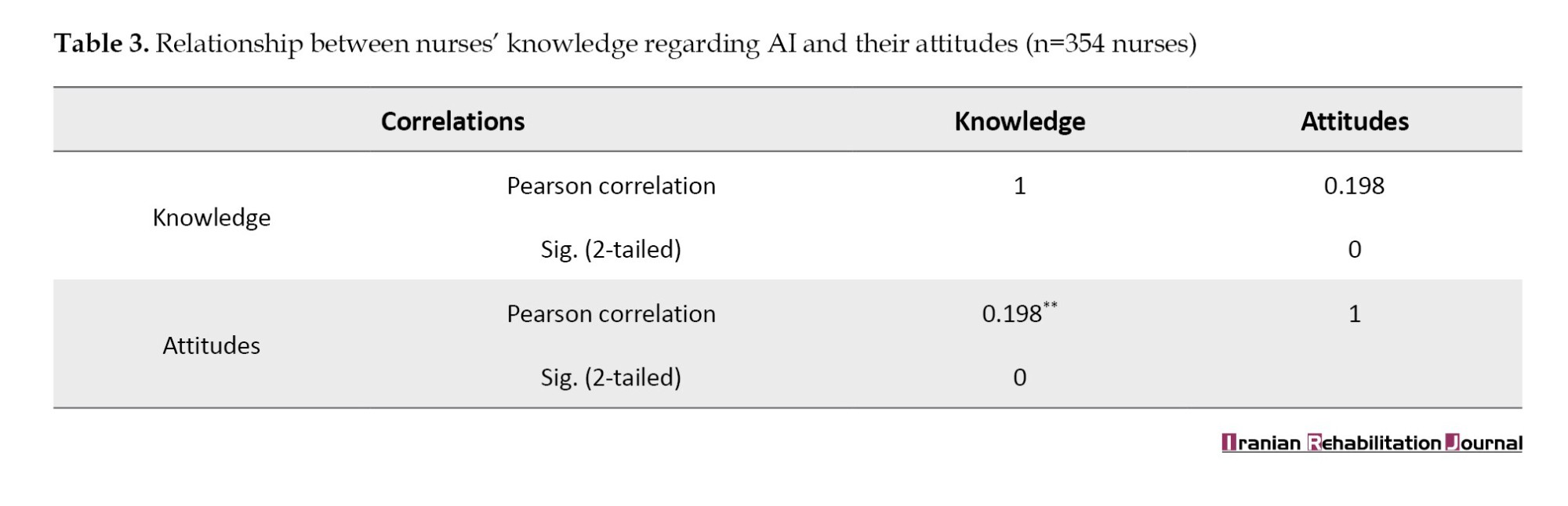

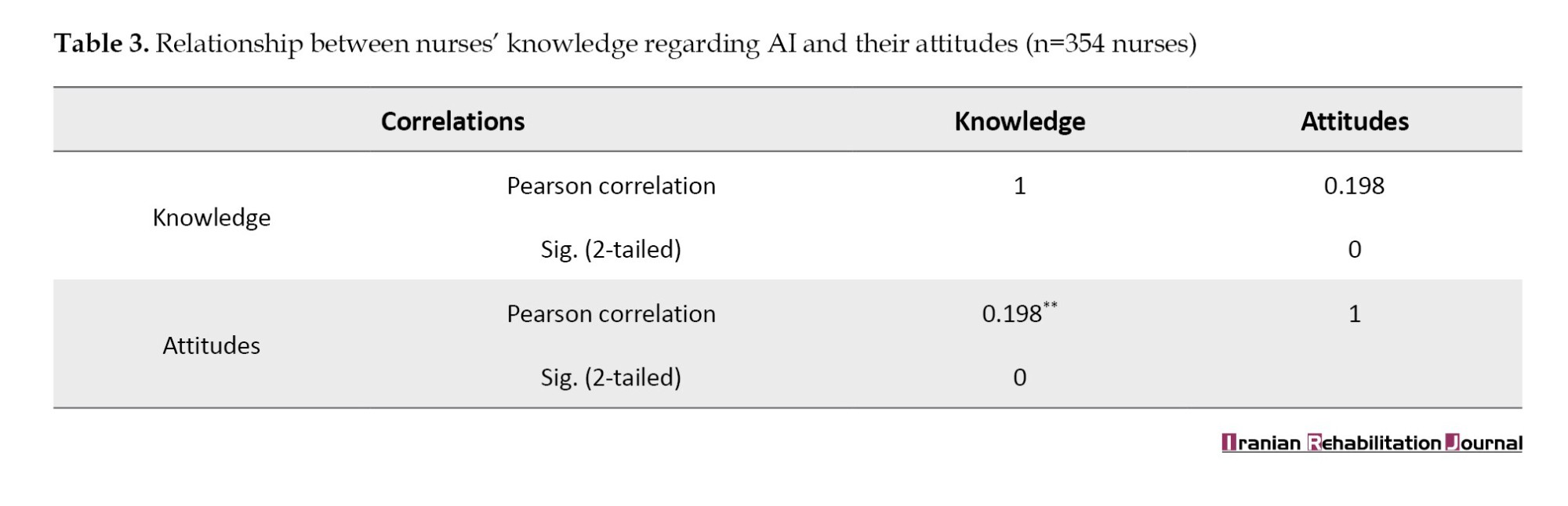

Table 3 presents the correlation between nurses' knowledge regarding AI and their attitudes towards it. The Pearson correlation coefficient is 0.198, indicating a positive relationship between knowledge and attitudes. The correlation is statistically significant, with a P of 0.000.

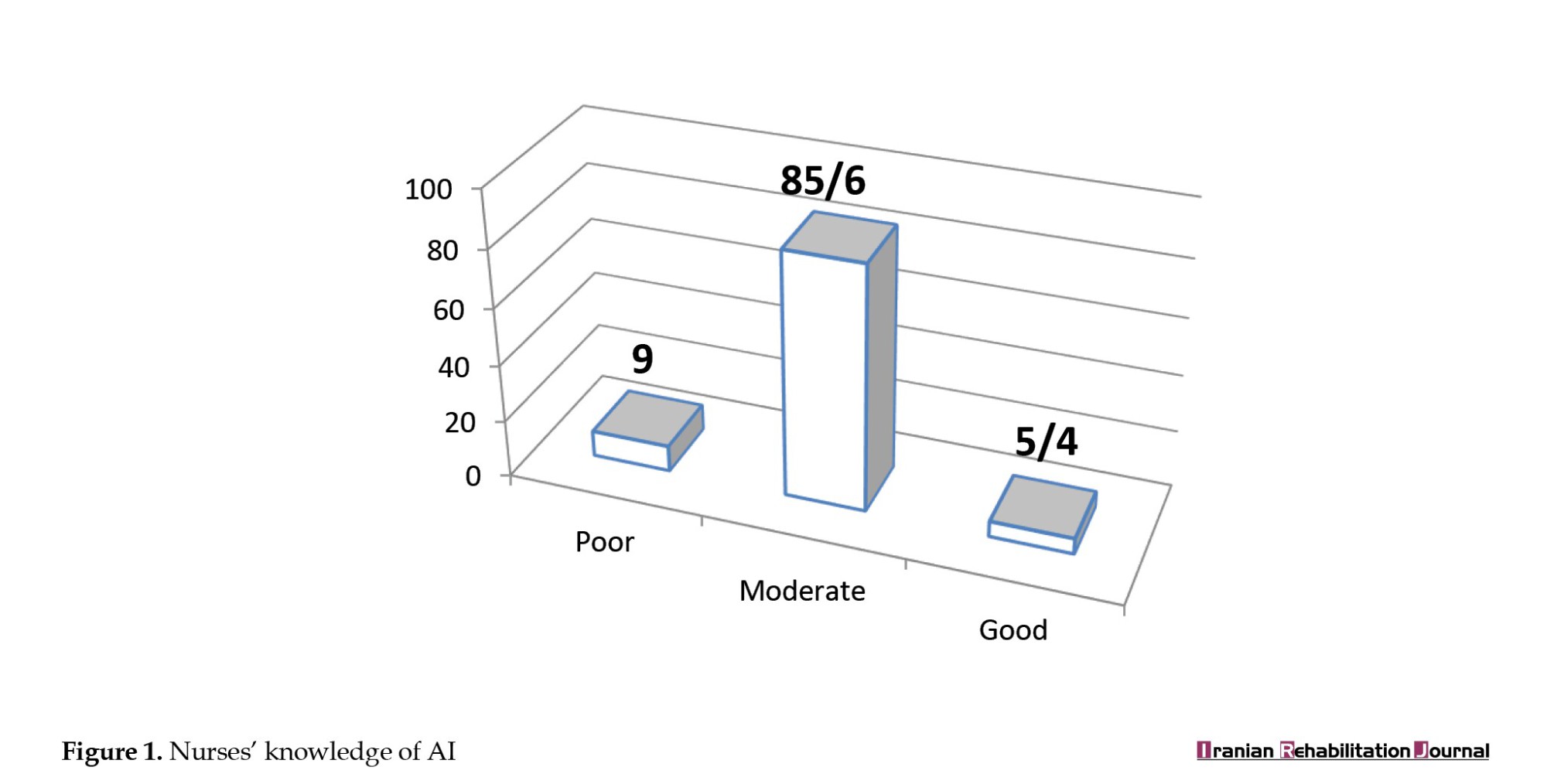

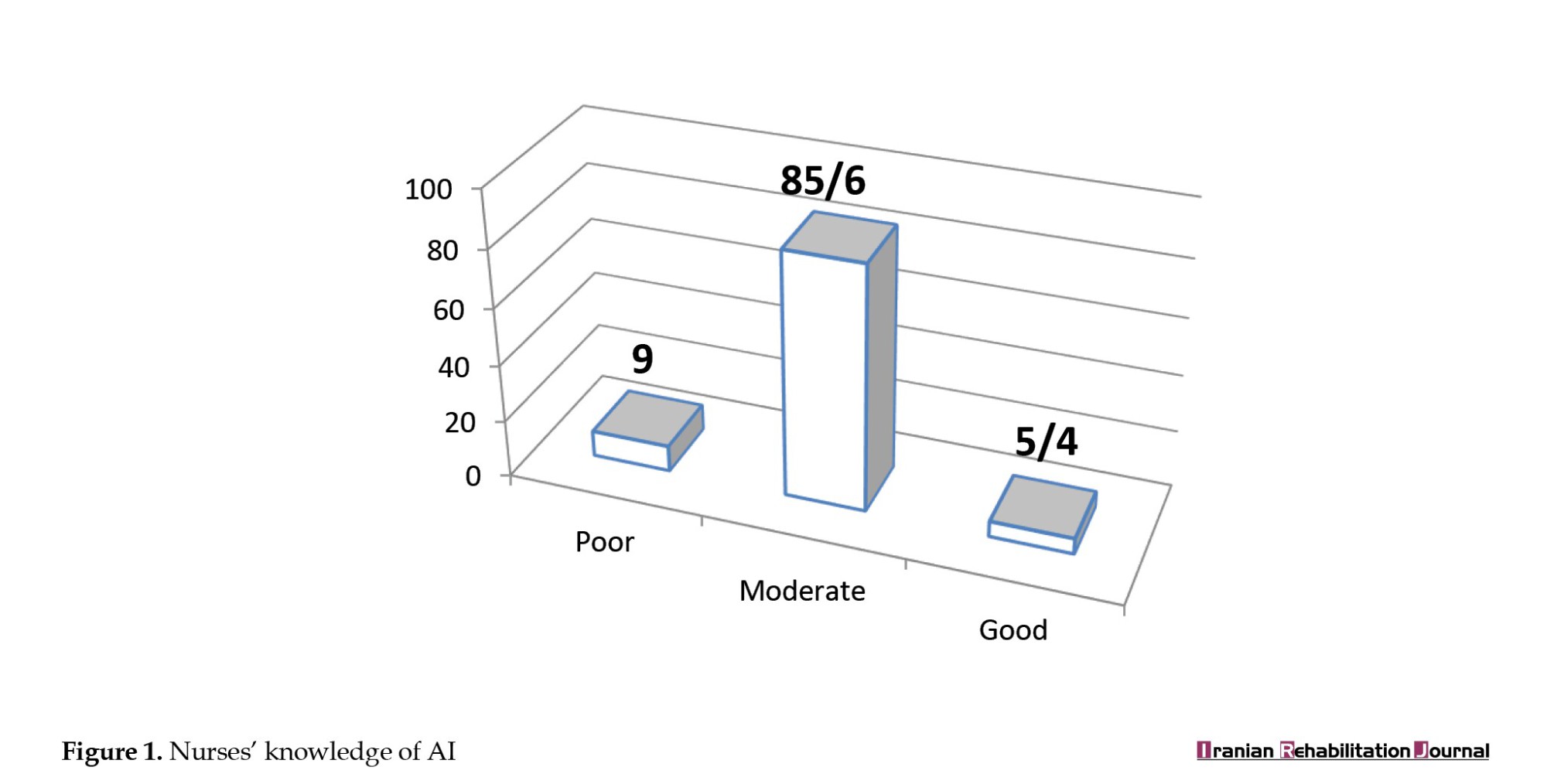

Figure 1 shows that most nurses moderately understand AI (85.6%). Only 9% were classified as having inadequate knowledge, and only 5.4% had good knowledge.

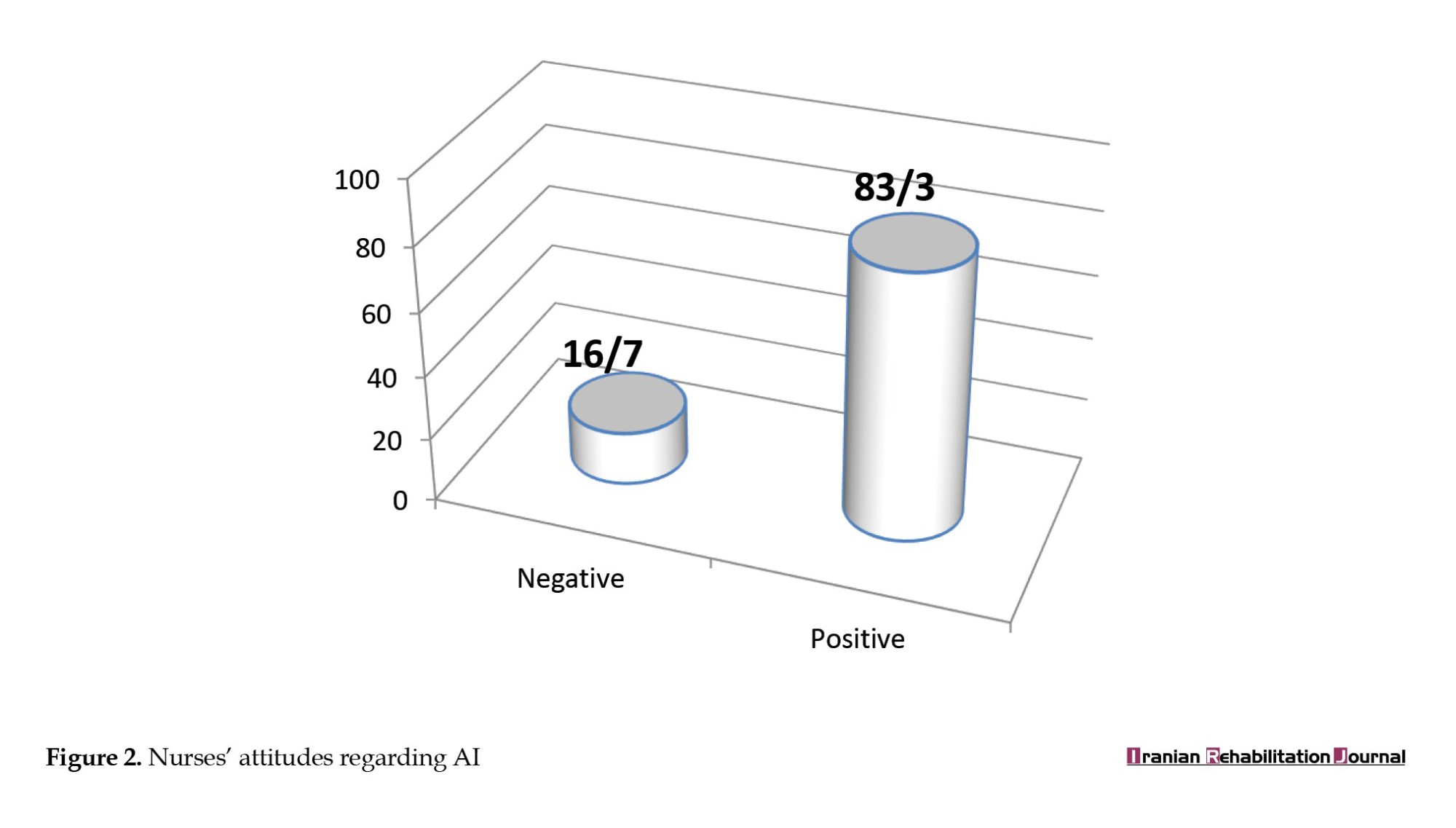

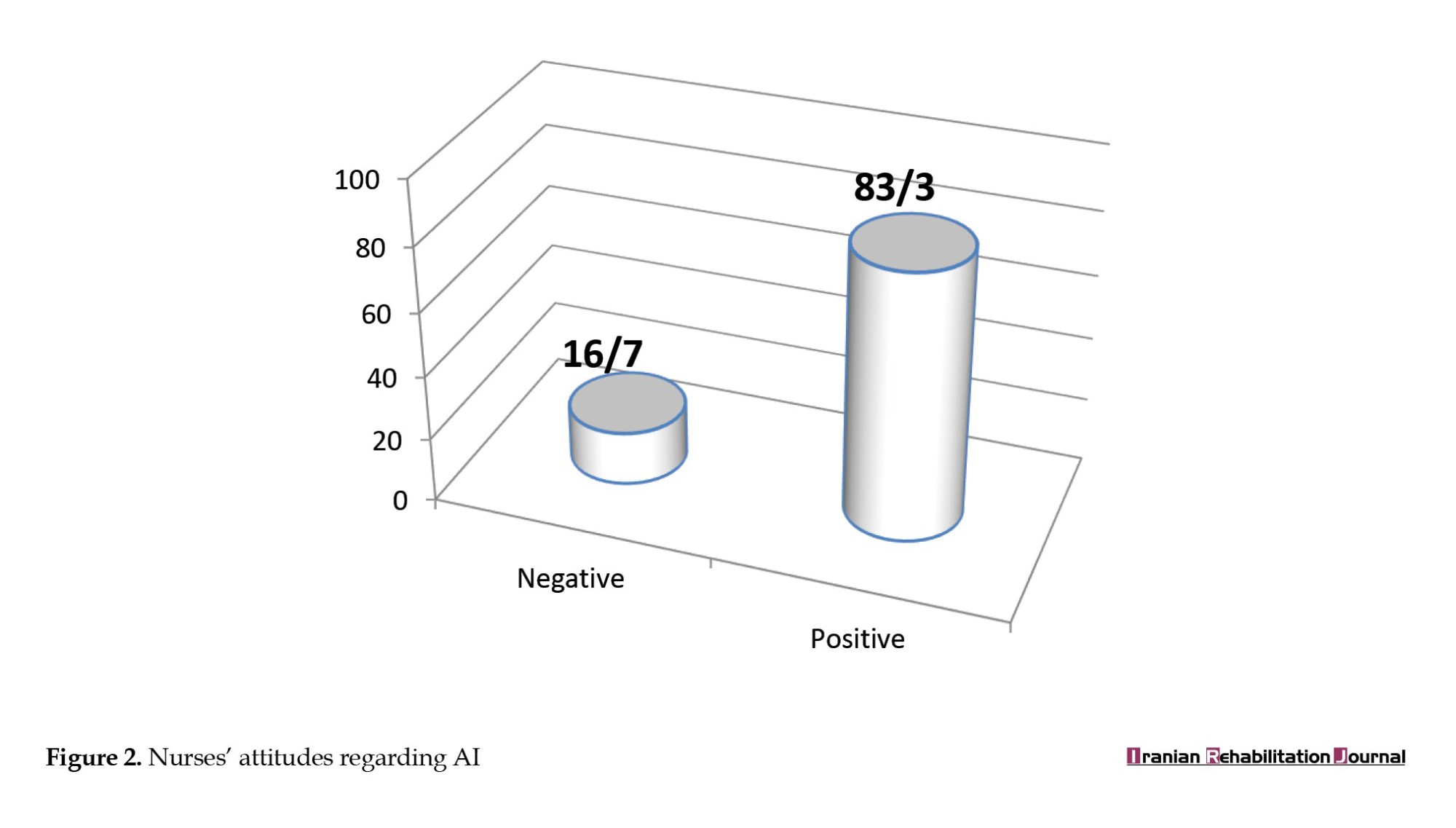

Figure 2 shows that most (83.3%) of the nurses had positive attitudes regarding AI, and 16.7% exhibited negative attitudes.

Discussion

The study participants were 354 staff nurses from the medical, surgical, intensive care unit (ICU), dialysis, maternal-child unit, and emergency departments. Analysis revealed that more than half of the study samples were 20-29 years, constituting 69.2% of all samples, 354 nurses. Most of the participants were nurses who had completed nursing school, and the primary cause of this was work age and productivity. The analysis is comparable to a study by Abd El-Monem et al. [11], which found that in terms of age, almost two-fifths (42) of staff nurses, whose average age was 28.63±7.21 years, were in the 25–30 age range. Regarding sex, most participants were female; they constituted the study sample (57.6%), and the males were (42.4%). The larger proportion of female nurses may have resulted from their perception of nursing as a female-dominated profession. This result agreed with that of a study conducted by Ahmed and Elderiny [12], who found that most participants in their study were female (51.3%), and the remaining were male (48.5%).

(57.6%) of the participants have experience (1-5) in nursing. Nurses rotating from one unit to another within the hospital could explain a few years of nursing experience in particular areas. This result is similar to that of the research conducted by Abdelkareem et al. [13], which showed that over half of the nurses had less than 10 years of experience. An additional study by Ünal and Avcı [14] revealed that over half (50.5%), had more than five years of job experience, averaging 6.89±4.49 years. Concerning educational qualification, the study sample revealed that most of the following factors led to the sample’s graduation from the nursing institute. Iraq has many medical institutions, although there are not many nursing degrees or universities that were established in the recent past. These results, in contrast with those obtained by Geneedy et al. [15], mentioned that regarding educational qualifications, over 50% of the nurses (58%) held a bachelor’s degree in nursing.

Concerning the division to which nurses were allocated, the results showed that nurses were distributed across various units, with the highest percentage (26.3%) in the emergency unit and the lowest in dialysis (10.5%). These results contradict those of a study by Alruwaili et al. [16], showing that the most common wards were the unit of critical care (CCU), ICU (22.7%), and medical/surgical ward (28.3%). Of the responses, 10% came from psychiatric units, 8.1% from obstetric/pediatric units, and 30.9% from all other units. Finally, the study revealed that most participating nurses lacked AI training. (94.4%), with only 5.4% attending one course and 0.3% attending two. The Mean±SD number of training courses attended was 0.05±0.248. These results are consistent with the study results conducted by Al-Sabawy [17], which found that the participants were not trained in AI.

Results indicated that most nurses (85.6%) had a moderate understanding of AI, with an average score of 20.58±1.796, falling within the moderate evaluation range (18.67–23.33). Only 9% of nurses were categorized as having poor knowledge (scores 14–18.66), while a small proportion (5.4%) demonstrated good knowledge (scores 23.34–28). These disagree with a study by Sommer et al. [18]; their research discovered that most nurses (73%) have a poor understanding of AI, while just 25.2% have substantial knowledge. Furthermore, this analysis disagrees with the study done in Egypt by Ali [19], which mentioned that more than half of the studied nursing personnel (58%) had unsatisfactory knowledge about AI. These results also differ from those of Abuzaid et al. [20], who discovered a deficiency in understanding AI. 75% of respondents thought that a basic understanding of AI should be taught in nursing programs.

The study showed that most nurses (83.3%) hold positive attitudes, with a mean score of 38.05±5.656, exceeding the threshold for positive assessment (>34). However, 16.7% of nurses exhibited negative attitudes, scoring ≤34. The nursing profession faces growing challenges from demographic changes and a lack of experienced staff. AI offers promising solutions to alleviate these pressures and decrease nurses’ stress. The study parallels with Abdelkareem et al. [13], who showed that more than two-thirds (86.7%) of critical care nurses had a positive attitude toward AI, while only a few had a negative attitude. The outcome did not match Ghazy et al. [21], who found that over half of nurse managers had a negative attitude toward using AI. Furthermore, these results were consistent with Al-Sabawy’s [17] results reporting that (84%) of the nurses demonstrated a positive attitude toward AI use in nursing practice.

The Mann-Whitney U-test indicated no significant differences in nurses’ understanding of AI relating to those who were male or female (P=0.235). This means that males and females had the same AI knowledge, regardless of sex. Furthermore, a substantial negative association between nurses’ understanding of AI and age. In contrast, Sommer et al. [18] stated that age does not function as a crucial factor and also found a substantial correlation between sex and AI understanding (Cramer’s V correlation of 0.335) (χ2 value=12.363, P=0.015).

According to educational background, a substantial positive association between nurses’ understanding of AI and their educational qualifications. The results of the current study are similar to those of Khan Rony et al. [8]. No significant relationship was found between nurses’ knowledge of AI and their years of experience (r=0.034, P=0.522). Because AI is a relatively new addition to healthcare, nurses who have been in the profession for many years may not have encountered it in their initial training or early career. These results are consistent with those obtained by Serbaya et al. [22], who found that no discernible variations were observed regarding AI knowledge ratings between years of expertise.

The test revealed a significant difference in AI knowledge between departments, with the dialysis unit showing the highest mean rank (261.47), followed by the surgical unit (206.52), the ICU, and other departments. Nurses working in dialysis, surgical, and ICUs have more knowledge than those in other departments because the complexity of care in these settings involves complex, high-level medical tasks. These results were similar to those obtained by Yaseen et al. [23]. A strong favorable association was found between nurses’ AI knowledge and the number of training courses (r=0.413, P=0.000). Related to the reality that training and education play a vital part in increasing nurses’ knowledge, this aids in fostering the acceptance and integration of AI technologies. This result contradicted the findings of Hamedani et al. [24], which showed no statistically significant relationships between knowledge and (P>0.05) participation in AI sessions.

The relationship between nurses’ opinions concerning AI and their knowledge of it was statistically significant, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.198 and a P=0.000. Consistent with findings from Khan Rony [8], strong associations were observed between favorable attitudes and understanding.

Conclusion

The study concluded that nurses’ positive attitudes toward AI and knowledge of the technology were moderate, depending on their age, educational background, training, and department. The study suggests training programs and workshops to help nurses learn more about AI and provides pertinent details regarding the advantages, challenges, and issues of integrating AI into nursing settings.

Study limitations

This study has some limitations. First, few articles have evaluated nurses’ attitudes and knowledge of AI in Iraq; the only study conducted in the Kirkuk Governorate examined nurses’ attitudes and perceptions regarding the use of AI. Additionally, because demographics and healthcare environments vary, the findings may not be generalized to all nurses and have limited generalizability. Employing non-random and convenience methods may lead to biased results.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the College of Nursing, University of Babylon, Babylon, Iraq (Code: 47 on 27/11/2024). They are required to safeguard subjects’ rights to the confidentiality of the data gathered and to advance the professional study that was carried out. The following ethical considerations apply based on protecting participants’ privacy, obtaining their voluntary consent, and creating questions that are clear and accessible given the nurses’ educational background and cultural background.

Funding

This research did not receive grants from public, commercial, or non-profit funding agencies.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants and data collectors for their full participation.

References

Artificial intelligence technology (AIT), a branch of computer science, uses computer systems to mimic the intelligence of healthcare team members. The three primary categories of this technology in the healthcare industry are natural language processing, deep learning, and machine learning. It automates several tasks, including learning and decision-making [1, 2]. Artificial intelligence (AI) can help with disease assessment, diagnosis, and solving various clinical issues in the healthcare industry. It can also reduce data loss, enhance patient safety, reduce nurse workload, enhance inpatient care management, and strengthen nursing communication skills [3]. The way the nursing profession is structured and organized has changed significantly as a result of technological advancements: Nursing is changing as a result of new ways to deliver healthcare in the modern era, including the use of electronic health records and the development of biomedical and engineering technologies that allow for the advancement of progressively sophisticated healthcare, robotic, and AI technologies [4]. AI is rapidly revolutionizing healthcare, and it can potentially revolutionize the nursing profession. According to empirical data, AI already impacts nursing practice, including nursing duties, clinical care, and nurse-patient interaction [5-7]. This study aims to assess nurses’ attitudes and knowledge about AI technology and investigate the relationship between nurses’ knowledge and attitudes regarding AI with socio-demographic variables.

Materials and Methods

The study design and setting

This qualitative cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted to assess nurses’ attitudes and knowledge about AIT using a questionnaire-based assessment approach at Al-Hilla Hospitals in Babylon Governorate from September 25, 2024, to April 1, 2025. The study was conducted at four hospitals in the Babylon Governorate (AL-Imam Sadiq Teaching Hospital, AL-Hilla Teaching Surgical Hospital, Marjan Hospital, and AL-Shomali General Hospital).

Study participants and sampling

A non-probability sampling technique chooses a convenient sample of 354 nurses. The study sample is spread among several hospital departments, such as the emergency room, critical care units, dialysis units, maternal and child units, and medical-surgical wards. Based on the total number of nurses in the four hospitals, 3122, the necessary sample size was 354 nurses, as determined using Slovin’s computation of sample size method (Equation 1):

1. n=N/1+N(e)2=354

n=corrected sample size. The size of the population is denoted by N. According to the study, circumstances at a 95% confidentiality level, e=error margin, and e=0.05.

Data collection and instrument tools

A questionnaire was developed after thoroughly analyzing the literature pertinent to the current investigation. The scale was used with slight modifications to a few items to make it suitable for this study. The questionnaire contains the following: Ι: The sociodemographic data questionnaire (SDVs) includes information, such as “number of training courses, unit/department, years of nursing experience, sex, age, and educational background.” ΙΙ: Nurse’s knowledge scale adapted by Rony et al. and Swed et al. [8, 9]; this section consists of 14 items to assess nurses’ knowledge regarding AI. ΙΙΙ: Nurses’ attitudes scale adapted by Schepman and Rodway [10]. This part consisted of 17 items to assess nurses’ attitudes regarding AI. A three-point Likert scale was used for rating and scoring to assess nurses’ attitudes regarding AI: Disagree, neutral, and agree. A two-point scale was used to rate the items. The items were rated as (yes and no), and the scale levels were scored as (2) for yes and (1) for no. Data were gathered using an adapted and created questionnaire (Arabic translation) to help the participants comprehend the study, following the completion of the necessary approvals. Additionally, the researchers translated all of the tools into Arabic and then back into English to ensure the instrument’s validity, the questionnaire was shown to ten panel members who were experts in the field: Two from the College of Nursing at Baghdad University, two from the Nursing College at Karbala University, two from the Nursing College at Kufa University, and two from the Nursing College at Babylon University. The experts revised the tools for their substance, clarity, simplicity, relevance, completeness, and applicability. They provided input, and minor adjustments were made. According to experts, the instruments were valid. Cronbach α was employed as a statistical tool to determine the questionnaire’s reliability; the result was 0.860 for the knowledge scale, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.880 for the attitude scale, indicating that the items’ high reliability and consistently capture the intended construct.

Data analysis

The researcher utilized the SPSS software, version 23 to perform a thorough statistical analysis of the data collected from the study sample and produced insightful findings through a series of exacting statistical tests (e.g. percentage, mean, frequency, Cronbach’s α, Kruskal-Wallis H test, the Mann-Whitney U analysis, the Pearson’s correlation coefficient), which were used to methodically examine the data, determine correlations between variables, and eventually produce the research’s definitive conclusions.

Results

Table 1 presents the distribution of the nurse samples based on their SDVs. The ages of the nurses ranged from 20 to over 50 years, with the majority (69.2%) being in the 20-29 age group, followed by 21.2% in the 30-39 age group. The Mean±SD age of the participants was 28.65±6.807 years. Regarding sex, 57.6% of the nurses were female, and 42.4% were male. Educational qualifications varied, with 48% holding a diploma in nursing, 30.8% having a bachelor’s degree, and smaller percentages holding secondary school nursing qualifications, a master’s, or a doctoral degree. Years of nursing experience show that 57.6% have less than 5 years of experience, with a Mean±SD experience of 5.67±5.748. The nurses were distributed across various units, with the highest percentage (26.3%) in the emergency unit and the lowest in dialysis (10.5%). Regarding training courses, a large majority (94.4%) did not attend any additional courses, with only 5.4% attending one course, and 0.3% attending two courses. The Mean±SD number of training courses attended was 0.05±0.248.

Table 2 presents a substantial association between nurses’ knowledge of AI and their sociodemographic variables (SDVs) regarding age (r=-0.139, P=0.009), educational qualification (r=0.147, P=0.006), departments (P=0.001), and number of training courses (r=0.413, P=0.000).

Table 3 presents the correlation between nurses' knowledge regarding AI and their attitudes towards it. The Pearson correlation coefficient is 0.198, indicating a positive relationship between knowledge and attitudes. The correlation is statistically significant, with a P of 0.000.

Figure 1 shows that most nurses moderately understand AI (85.6%). Only 9% were classified as having inadequate knowledge, and only 5.4% had good knowledge.

Figure 2 shows that most (83.3%) of the nurses had positive attitudes regarding AI, and 16.7% exhibited negative attitudes.

Discussion

The study participants were 354 staff nurses from the medical, surgical, intensive care unit (ICU), dialysis, maternal-child unit, and emergency departments. Analysis revealed that more than half of the study samples were 20-29 years, constituting 69.2% of all samples, 354 nurses. Most of the participants were nurses who had completed nursing school, and the primary cause of this was work age and productivity. The analysis is comparable to a study by Abd El-Monem et al. [11], which found that in terms of age, almost two-fifths (42) of staff nurses, whose average age was 28.63±7.21 years, were in the 25–30 age range. Regarding sex, most participants were female; they constituted the study sample (57.6%), and the males were (42.4%). The larger proportion of female nurses may have resulted from their perception of nursing as a female-dominated profession. This result agreed with that of a study conducted by Ahmed and Elderiny [12], who found that most participants in their study were female (51.3%), and the remaining were male (48.5%).

(57.6%) of the participants have experience (1-5) in nursing. Nurses rotating from one unit to another within the hospital could explain a few years of nursing experience in particular areas. This result is similar to that of the research conducted by Abdelkareem et al. [13], which showed that over half of the nurses had less than 10 years of experience. An additional study by Ünal and Avcı [14] revealed that over half (50.5%), had more than five years of job experience, averaging 6.89±4.49 years. Concerning educational qualification, the study sample revealed that most of the following factors led to the sample’s graduation from the nursing institute. Iraq has many medical institutions, although there are not many nursing degrees or universities that were established in the recent past. These results, in contrast with those obtained by Geneedy et al. [15], mentioned that regarding educational qualifications, over 50% of the nurses (58%) held a bachelor’s degree in nursing.

Concerning the division to which nurses were allocated, the results showed that nurses were distributed across various units, with the highest percentage (26.3%) in the emergency unit and the lowest in dialysis (10.5%). These results contradict those of a study by Alruwaili et al. [16], showing that the most common wards were the unit of critical care (CCU), ICU (22.7%), and medical/surgical ward (28.3%). Of the responses, 10% came from psychiatric units, 8.1% from obstetric/pediatric units, and 30.9% from all other units. Finally, the study revealed that most participating nurses lacked AI training. (94.4%), with only 5.4% attending one course and 0.3% attending two. The Mean±SD number of training courses attended was 0.05±0.248. These results are consistent with the study results conducted by Al-Sabawy [17], which found that the participants were not trained in AI.

Results indicated that most nurses (85.6%) had a moderate understanding of AI, with an average score of 20.58±1.796, falling within the moderate evaluation range (18.67–23.33). Only 9% of nurses were categorized as having poor knowledge (scores 14–18.66), while a small proportion (5.4%) demonstrated good knowledge (scores 23.34–28). These disagree with a study by Sommer et al. [18]; their research discovered that most nurses (73%) have a poor understanding of AI, while just 25.2% have substantial knowledge. Furthermore, this analysis disagrees with the study done in Egypt by Ali [19], which mentioned that more than half of the studied nursing personnel (58%) had unsatisfactory knowledge about AI. These results also differ from those of Abuzaid et al. [20], who discovered a deficiency in understanding AI. 75% of respondents thought that a basic understanding of AI should be taught in nursing programs.

The study showed that most nurses (83.3%) hold positive attitudes, with a mean score of 38.05±5.656, exceeding the threshold for positive assessment (>34). However, 16.7% of nurses exhibited negative attitudes, scoring ≤34. The nursing profession faces growing challenges from demographic changes and a lack of experienced staff. AI offers promising solutions to alleviate these pressures and decrease nurses’ stress. The study parallels with Abdelkareem et al. [13], who showed that more than two-thirds (86.7%) of critical care nurses had a positive attitude toward AI, while only a few had a negative attitude. The outcome did not match Ghazy et al. [21], who found that over half of nurse managers had a negative attitude toward using AI. Furthermore, these results were consistent with Al-Sabawy’s [17] results reporting that (84%) of the nurses demonstrated a positive attitude toward AI use in nursing practice.

The Mann-Whitney U-test indicated no significant differences in nurses’ understanding of AI relating to those who were male or female (P=0.235). This means that males and females had the same AI knowledge, regardless of sex. Furthermore, a substantial negative association between nurses’ understanding of AI and age. In contrast, Sommer et al. [18] stated that age does not function as a crucial factor and also found a substantial correlation between sex and AI understanding (Cramer’s V correlation of 0.335) (χ2 value=12.363, P=0.015).

According to educational background, a substantial positive association between nurses’ understanding of AI and their educational qualifications. The results of the current study are similar to those of Khan Rony et al. [8]. No significant relationship was found between nurses’ knowledge of AI and their years of experience (r=0.034, P=0.522). Because AI is a relatively new addition to healthcare, nurses who have been in the profession for many years may not have encountered it in their initial training or early career. These results are consistent with those obtained by Serbaya et al. [22], who found that no discernible variations were observed regarding AI knowledge ratings between years of expertise.

The test revealed a significant difference in AI knowledge between departments, with the dialysis unit showing the highest mean rank (261.47), followed by the surgical unit (206.52), the ICU, and other departments. Nurses working in dialysis, surgical, and ICUs have more knowledge than those in other departments because the complexity of care in these settings involves complex, high-level medical tasks. These results were similar to those obtained by Yaseen et al. [23]. A strong favorable association was found between nurses’ AI knowledge and the number of training courses (r=0.413, P=0.000). Related to the reality that training and education play a vital part in increasing nurses’ knowledge, this aids in fostering the acceptance and integration of AI technologies. This result contradicted the findings of Hamedani et al. [24], which showed no statistically significant relationships between knowledge and (P>0.05) participation in AI sessions.

The relationship between nurses’ opinions concerning AI and their knowledge of it was statistically significant, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.198 and a P=0.000. Consistent with findings from Khan Rony [8], strong associations were observed between favorable attitudes and understanding.

Conclusion

The study concluded that nurses’ positive attitudes toward AI and knowledge of the technology were moderate, depending on their age, educational background, training, and department. The study suggests training programs and workshops to help nurses learn more about AI and provides pertinent details regarding the advantages, challenges, and issues of integrating AI into nursing settings.

Study limitations

This study has some limitations. First, few articles have evaluated nurses’ attitudes and knowledge of AI in Iraq; the only study conducted in the Kirkuk Governorate examined nurses’ attitudes and perceptions regarding the use of AI. Additionally, because demographics and healthcare environments vary, the findings may not be generalized to all nurses and have limited generalizability. Employing non-random and convenience methods may lead to biased results.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the College of Nursing, University of Babylon, Babylon, Iraq (Code: 47 on 27/11/2024). They are required to safeguard subjects’ rights to the confidentiality of the data gathered and to advance the professional study that was carried out. The following ethical considerations apply based on protecting participants’ privacy, obtaining their voluntary consent, and creating questions that are clear and accessible given the nurses’ educational background and cultural background.

Funding

This research did not receive grants from public, commercial, or non-profit funding agencies.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants and data collectors for their full participation.

References

- Dash S, Shakyawar SK, Sharma M, Kaushik S. Big data in healthcare: Management, analysis and future prospects. Journal of Big Data. 2019; 6(1):1-25. [DOI:10.1186/s40537-019-0217-0]

- Maddox TM, Rumsfeld JS, Payne PRO. Questions for artificial intelligence in health care. JAMA. 2019; 321(1):31-2. [DOI:10.1001/jama.2018.18932] [PMID]

- Zhou J, Zhang F, Wang H, Yin Y, Wang Q, Yang L, et al. Quality and efficiency of a standardized e‐handover system for pediatric nursing: A prospective interventional study. Journal of Nursing Management. 2022; 30(8):3714-25 [DOI:10.1111/jonm.13549] [PMID]

- Pepito JA, Locsin R. Can nurses remain relevant in a technologically advanced future? International Journal of Nursing Sciences. 2018; 6(1):106-10. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnss.2018.09.013] [PMID]

- Abuzaid MM, Elshami W, Tekin HO. Infection control and radiation safety practices in the radiology department during the COVID-19 outbreak. Plos One. 2022; 17(12):e0279607 [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0279607] [PMID]

- Buchanan TW, McMullin SD, Baxley C, Weinstock J. Stress and gambling. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 2020; 31:8-12. [DOI:10.1016/j.cobeha.2019.09.004]

- Ng ZQP, Ling LYJ, Chew HSJ, Lau Y. The role of artificial intelligence in enhancing clinical nursing care: A scoping review. Journal of Nursing Management. 2022; 30(8):3654-74. [DOI:10.1111/jonm.13425] [PMID]

- Khan Rony MK, Akter K, Nesa L, Islam MT, Johra FT, Akter F, et al. Healthcare workers’ knowledge and attitudes regarding artificial intelligence adoption in healthcare: A cross-sectional study. Heliyon. 2024; 10(23):e40775. [DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e40775] [PMID]

- Swed S, Alibrahim H, Elkalagi NK, Nasif MN, Rais MA, Nashwan AJ, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of artificial intelligence among doctors and medical students in Syria: A cross-sectional online survey. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence. 2022; 5:1011524. [DOI:10.3389/frai.2022.1011524] [PMID]

- Schepman A, Rodway P. Initial validation of the general attitudes towards Artificial Intelligence Scale. Computers in Human Behavior Reports. 2020; 1:100014. [DOI:10.1016/j.chbr.2020.100014] [PMID]

- Mohamed Abd El-Monem A, Elsayed Rashed S, Ghoneimy Hasanin A. Artificial intelligence technology and its relation to staff nurses’ professional identity and problem solving abilities. International Egyptian Journal of Nursing Sciences and Research. 2023; 3(2):144-64. [DOI:10.21608/ejnsr.2023.277890]

- Ahmed SA, Elderiny SN. Intensive care nurses’ knowledge and perception regarding artificial intelligence applications. Trends in Nursing and Health Care Journal. 2024; 8(1):195-220. [DOI:10.21608/tnhcj.2024.250044.1038]

- Abdelkareem SA, Bakri MH, Ahmed NA. Perception and attitudes of critical care nurses regarding artificial intelligence at intensive care unit. Assiut Scientific Nursing Journal. 2024; 12(43):163-71. [DOI:10.21608/asnj.2024.268448.1782]

- Ünal AS, Avcı A. Evaluation of neonatal nurses’ anxiety and readiness levels towards the use of artificial intelligence. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2024; 79:e16-e23. [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2024.09.012] [PMID]

- Mohammed Gomaa Geneedy E, El-Sayed Mohammed Hemaida W, Elsayed Aboelfetoh E. Implementation of an educational program for operating room nurses to improve perception and attitudes towards integrating artificial intelligence in nursing practice. Egyptian Journal of Health Care. 2024; 15(2):1854-75. [DOI:10.21608/ejhc.2024.394709]

- Alruwaili MM, Abuadas FH, Alsadi M, Alruwaili AN, Elsayed Ramadan OM, Shaban M, et al. Exploring nurses’ awareness and attitudes toward artificial intelligence: Implications for nursing practice. Digital Health. 2024; 10:20552076241271803. [DOI:10.1177/20552076241271803] [PMID]

- Al-Sabawy MR. Artificial intelligence in nursing: A study on nurses’ perceptions and readiness. Paper presented at: 1st International and 6th Scientific Conference of Kirkuk Health Directorate. January 2023; kirkuk, Iraq. [Link]

- Sommer D, Schmidbauer L, Wahl F. Nurses’ perceptions, experience and knowledge regarding artificial intelligence: Results from a cross-sectional online survey in Germany. BMC Nursing. 2024; 23(1):205. [DOI:10.1186/s12912-024-01884-2] [PMID]

- Ali FN. Artificial intelligence in nursing practice: Challenges and barriers. Helwan International Journal for Nursing Research and Practice. 2024; 3(7):217-30. [DOI:10.21608/hijnrp.2024.292923.1169]

- Abuzaid MM, Elshami W, Fadden SM. Integration of artificial intelligence into nursing practice. Health and Technology. 2022; 12(6):1109-15. [DOI:10.1007/s12553-022-00697-0] [PMID]

- Ghazy DA, Diab GM, Shokry WM. Perception and attitudes of nurse managers toward artificial intelligence technology at selected hospitals. Menoufia Nursing Journal. 2023; 8(3):357-73. [DOI:10.21608/menj.2023.334080]

- Serbaya SH, Khan AA, Surbaya SH, Alzahrani SM. Knowledge, attitude and practice toward artificial intelligence among healthcare workers in private polyclinics in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Advances in Medical Education and Practice. 2024; 15:269-80. [DOI:10.2147/AMEP.S448422] [PMID]

- Yaseen MM, Alsharif FH, Altaf RA, Asiri TW, Bagies RM, Alharbi SB, et al. Assessing nurses’ knowledge regarding the application of artificial intelligence among nursing practice. Nursing Research and Practice. 2025; 2025:9371969.[DOI:10.1155/nrp/9371969] [PMID]

- Hamedani Z, Moradi M, Kalroozi F, Manafi Anari A, Jalalifar E, Ansari A, et al. Evaluation of acceptance, attitude, and knowledge towards artificial intelligence and its application from the point of view of physicians and nurses: A provincial survey study in Iran: A cross‐sectional descriptive‐analytical study. Health Science Reports.2023; 6(9):e1543.[DOI:10.1002/hsr2.1543]

Article type: Original Research Articles |

Subject:

Nursing

Received: 2025/03/19 | Accepted: 2025/04/21 | Published: 2025/06/1

Received: 2025/03/19 | Accepted: 2025/04/21 | Published: 2025/06/1

Send email to the article author