Volume 23, Issue 4 (December 2025)

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2025, 23(4): 419-430 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Guerrero-Jaramillo D, Guerrero P, Benavides-Cordoba V. The Influence of Job Relation Types on Quality of Life and Job Precariousness in Rehabilitation Professionals. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2025; 23 (4) :419-430

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2515-en.html

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2515-en.html

1- Department of Occupational Health, District Secretariat of Public Health, Cali, Colombia.

2- Department of Planning, District Secretariat of Public Health, Cali, Colombia.

3- Department of Physiological Sciences, School of Basic Sciences, University of Valle, Cali, Colombia.

2- Department of Planning, District Secretariat of Public Health, Cali, Colombia.

3- Department of Physiological Sciences, School of Basic Sciences, University of Valle, Cali, Colombia.

Full-Text [PDF 489 kb]

(277 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (976 Views)

Full-Text: (61 Views)

Introduction

Employment growth in the health sector can generate multiple benefits: It improves health outcomes, drives economic growth, and promotes equity, especially for women and young people. According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO), 40 million health jobs are expected by 2030, mainly in middle- and high-income countries. However, in low-income countries, defined by the World Bank as those with a gross national income per capita of 1,135 USD or less, there are two problems: A shortage of health workers and the precariousness of the jobs provided. Therefore, the priority is not only to create new jobs but also to promote formality and equity among workers in the same area [1].

The different types of contractual modalities that began to emerge as a result of the phenomenon of globalization have led to a greater number of workers with unstable jobs and a significant decrease in their income, making it difficult for them to maintain a dignified standard of living and affecting their families and social environments [2, 3].

Work precariousness resulting from new forms of employment generates stress in workers not only due to pressures within the workplace, but also because such precariousness prevents them from achieving a decent quality of life (QoL), which allows them to meet human needs in terms of acquiring goods and services for themselves and their families, as well as time for themselves and their families as well as for self-care [4]. This situation, particularly among healthcare workers, has clinical implications due to the stress generated, such as cardiovascular diseases [5], depression, anxiety, and other mental health disorders [6], and changes in social and health-related behaviors [7], and absenteeism [8].

In Europe, it has been found that the desire to leave the profession increases when workers perceive a high workload, insufficient rewards, and rising job demands [9]. In Latin America, a relationship has been identified between low motivation and labor conflicts, triggered by work overload and insufficient resources for work operations, as factors that contribute to professional burnout in health workers [10].

Quality of working life (QWL) refers to employees’ attitudes towards their work, including development, talent utilization, compensation, and well-being. It is linked to job satisfaction (JS) and perceptions of justice in the organization. Improving QWL and organizational performance is essential, especially in the healthcare sector, where productivity must be increased due to staff shortages. Nursing managers can help meet these challenges by improving human resource management and planning [11].

In Colombia, companies hire workers through different contracts. Some guarantee stability and legal benefits, while others are limited to the payment for a service. In practice, situations often arise where workers perform the functions of a formal employment relationship but are hired under service contracts, a condition known as a real or “emerging contract,” defined in this study as a modality in which workers assume the duties of employees without access to the corresponding labor rights or benefits [12].

The present study aims to investigate whether differences in the type of contract influence QOL, considering both workers with formal contracts and those who operate under real contracts, which are all professionals in human rehabilitation. Through this analysis, we aimed to identify whether the working conditions associated with different types of contracts significantly impact employee well-being and satisfaction. While similar studies exist in Europe and Latin America, Colombia presents a distinct context due to widespread informal labor practices in the health sector. This research is necessary to provide local evidence, identify the impact of emerging contracts, and inform labor policy within Colombia’s specific legal and social frameworks.

Materials and Methods

This was an observational cross-sectional study that included professionals in physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy who worked in health, education, and social projects and had at least one year of work experience in the field. The one-year minimum was established to ensure that participants had sufficient exposure to their contractual conditions and institutional environment, allowing for a meaningful assessment of how these factors impacted their QWL. The decision to focus on these specific rehabilitation disciplines was based on their prevalence in the Colombian labor market and their substantial representation in public and private institutions. Including a broader spectrum of specialties may have diluted the focus and statistical power of the analysis. The questionnaires were applied in person using printed forms under the supervision of the researchers between January 2018 and February 2021. The study was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the Universidad del Valle (Colombia); and followed the STROBE guidelines [13]. All participants entered voluntarily and signed informed consent.

This study focused on three types of contracts common in Colombia:

1) Employment contract guarantees labor rights such as social security, paid leave, and job stability; 2) Independent contract: Where professionals are considered service providers without subordination, and, therefore, do not receive benefits like paid leave or severance; 3) Emerging contract, a term used in this study to classify individuals who, while officially hired as independent contractors, fulfilled all the conditions of a real employment relationship. These include subordination, company-assigned tasks, and periodic remuneration, as defined in Articles 23-26 of the Colombian Substantive Labor Code.

Although Colombia also uses other hiring modalities, such as fixed-term, temporary agency contracts, and contracts by commission, this study focused on the three types mentioned above because they are the most frequently used in the rehabilitation sector. These types were of particular interest due to their ambiguous nature and the potential for labor rights violations in emerging contracts.

Sampling combined probabilistic and non-probabilistic methods. Initially, a required sample size of 187 participants was calculated, derived from a population frame of 3845 professionals registered in the territorial entity between 1994 and 2017, with a precision of 95%, a significance level of 5% and an error of 7%. Due to access limitations, recruitment followed a snowball strategy. This method began with participants selected from predefined criteria, who received the questionnaires and were instructed to refer others who met the same inclusion criteria. This strategy allowed us to reach the projected sample size by progressively expanding the network of participants through recommendations. To ensure consistency and accuracy in data collection, all questionnaires were self-administered under supervision when possible, or completed remotely under clear instructions sent by email or messaging platforms. Participants were instructed to complete the instruments in a single session in a quiet environment. A detailed explanation of the objectives and instructions was provided before completion, and contact was maintained for clarification if needed. Incomplete or inconsistent responses were reviewed and, when necessary, validated directly with respondents.

We collected sociodemographic and labor information from all participants and classified them based on their employment contracts. This classification was based on the information provided by each professional, specifically those who self-identified as having either an employment or an independent contract. To identify whether the participant had an emerging form of contract, a questionnaire on the budget of a real contract was applied.

This questionnaire was designed based on articles 23-26 of the Colombian Substantive Labor Code. The interview was structured around the three key elements required to establish an employment relationship: Alignment with the company’s core mission, subordination to an employer, and receipt of regular wages. Responses were assessed using a checklist to ensure consistency across participants. The tool was validated by a labor law judge in Colombia with expertise in employment classification to ensure rigorous application of legal criteria. Additionally, two psychologists with experience in occupational health reviewed the instrument to ensure clarity, coherence, and relevance of the items.

Participants who met all three items (core mission, subordination and regular wages) were included in the emerging contract group. The “quality of life at work-GOHISALO” (CVT-GOHISALO) questionnaire was then applied. This instrument was designed to comprehensively measure the quality of work life, addressing various aspects of the work environment that may affect workers’ well-being. The CVT-GOHISALO has demonstrated solid psychometric properties, with a reported Cronbach’s α of 0.91 for the overall instrument and values above 0.7 for each dimension. Its construct validity was supported through factorial analysis, and it has been widely used in occupational health research in Latin America, particularly in Colombia and Mexico. This instrument assesses seven key dimensions: Working conditions, job stress, relationship with coworkers, satisfaction with salary, workload, training and professional development, and work-life balance. It consists of a Likert-type scale with 74 items in seven dimensions, giving a value from 0 to 4, where zero is not satisfied and four is completely satisfied. The score is represented in percentile values; the 50th percentile represents the average with a deviation of 10. Thus, a T<40 was considered low, between 40 and 60 medium, and more than 60 was considered a high score [14].

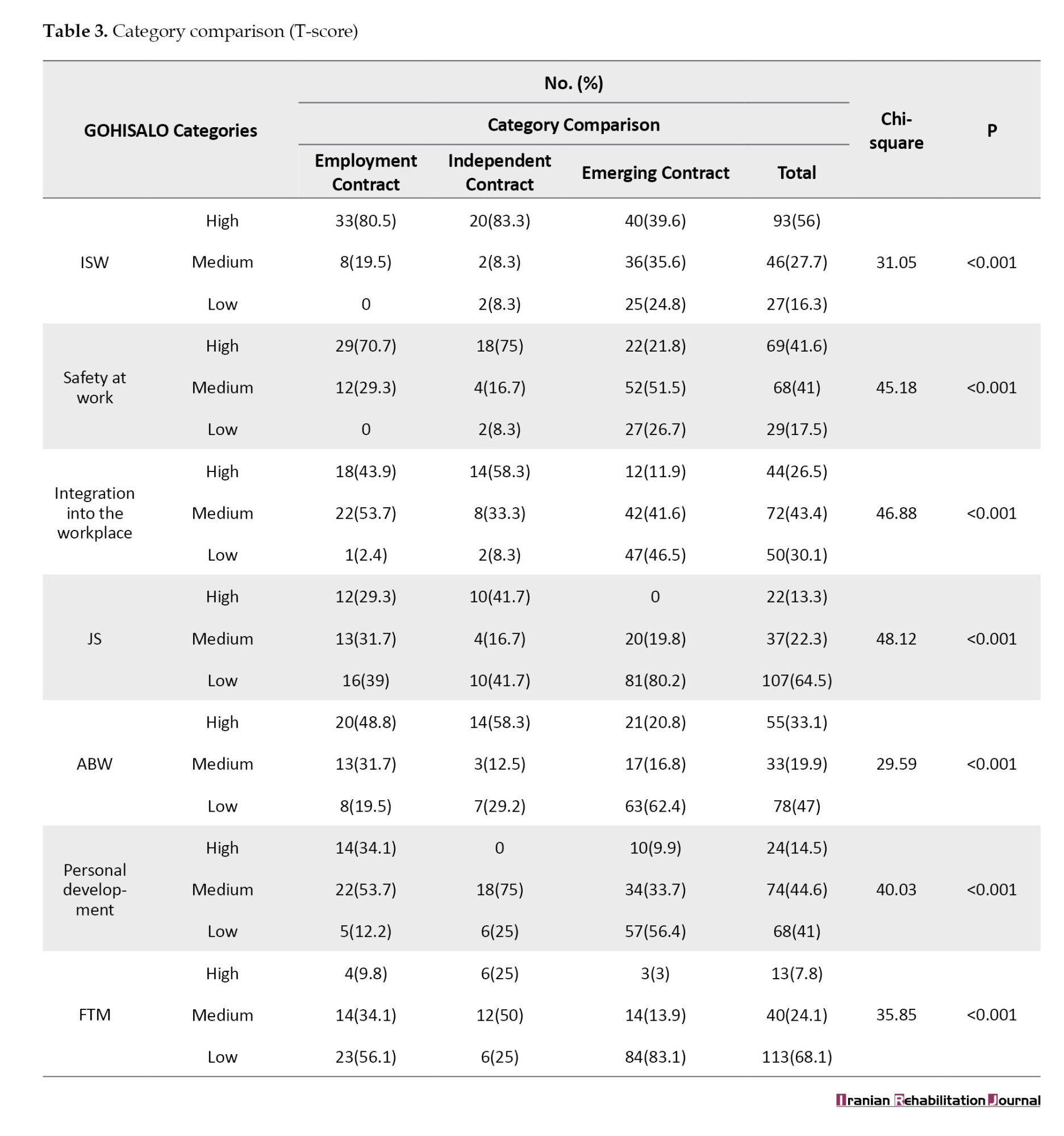

To facilitate comparative analysis between employment groups, each of the seven dimensions assessed by the GOHISALO, according to the authors [14] was categorized into three levels: Low (T-score<40), medium (T-score 40–60), and high (T-score >60). These categories allowed us to analyze the distribution of perceived QoL using frequency data.

The dimensions evaluated were institutional support for work (ISW), job security, integration into the workplace (IW), Job satisfaction, well-being achieved through work (ABW), personal development of the worker, free time management (FTM), and the total score. Once scored, it was assessed individually and then generally, highlighting the most critical dimensions that generated a perception of dissatisfaction on the part of the worker.

Qualitative variables, such as sex, profession, marital status, contractual modality, and type of institution, were presented as frequencies and percentages. Quantitative variables, including age and total and dimensional scores of the GOHISALO questionnaire, are presented as Mean±SD. Prior to performing inferential statistics, normality tests were applied using the D’Agostino-Pearson test. For variables with abnormal distribution, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used; otherwise, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied for normally distributed variables. Group comparisons of proportions obtained from the CVT-GOHISALO T score were conducted using M×N tables and the Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test. All analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 20.

Results

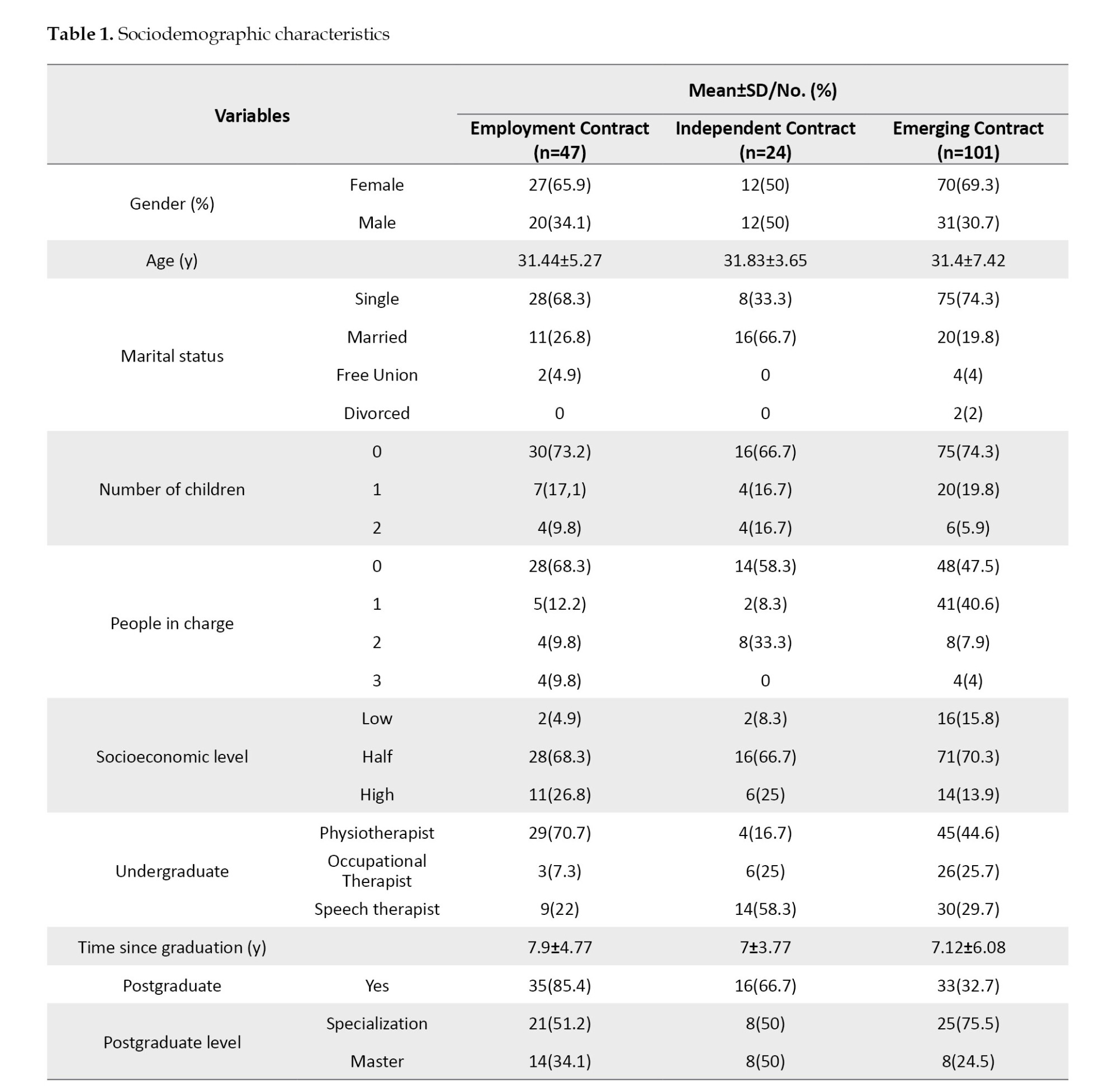

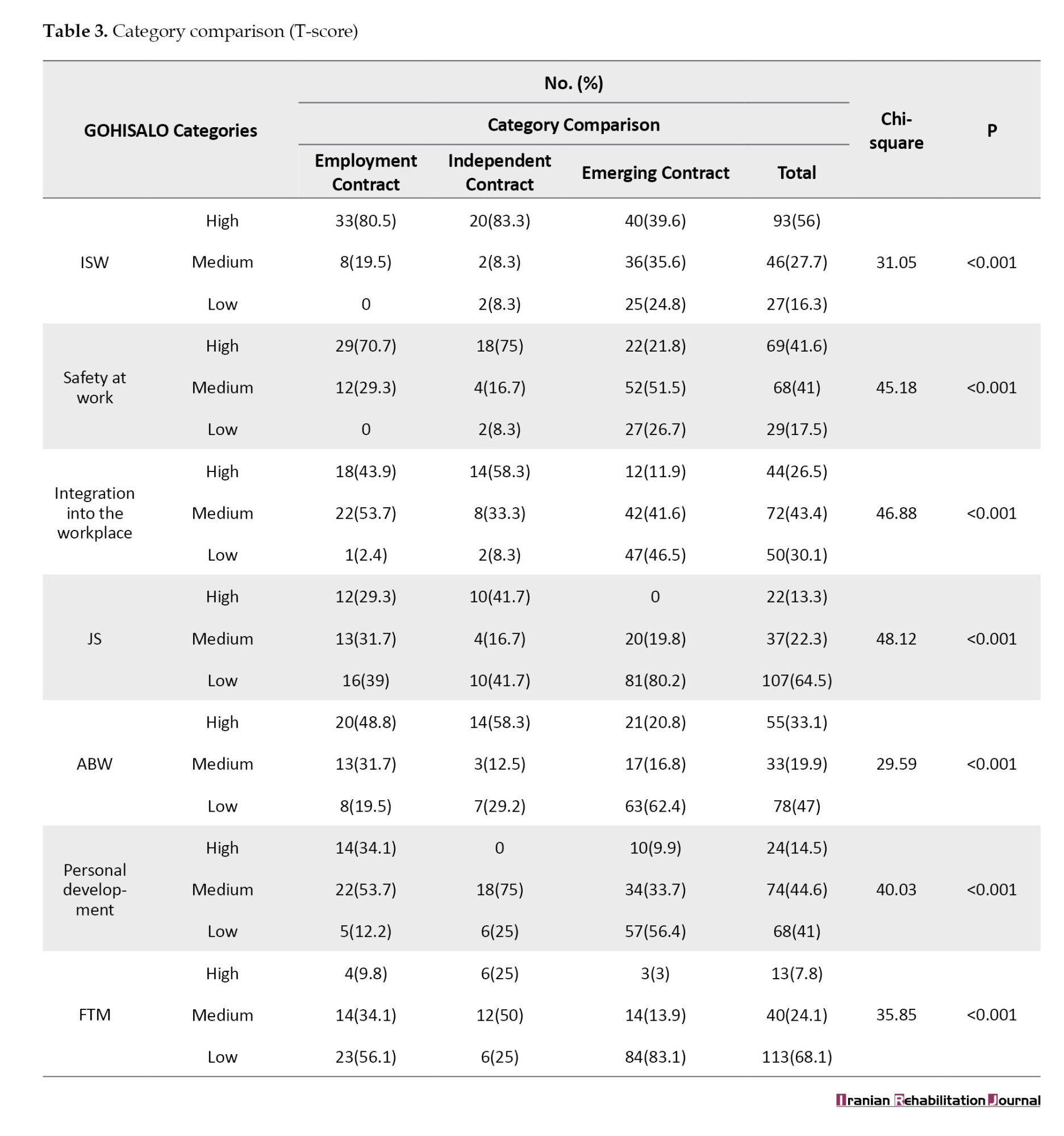

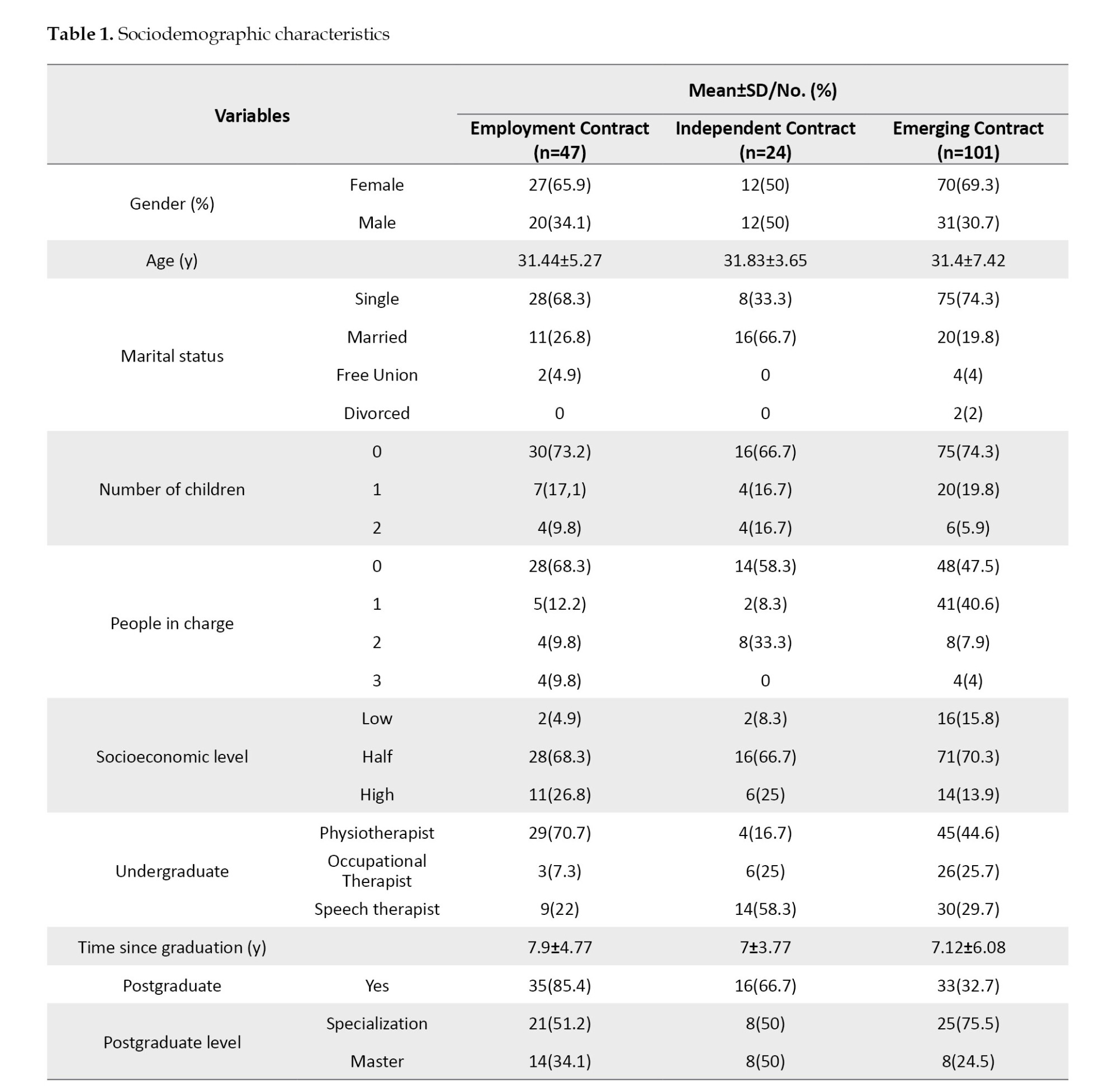

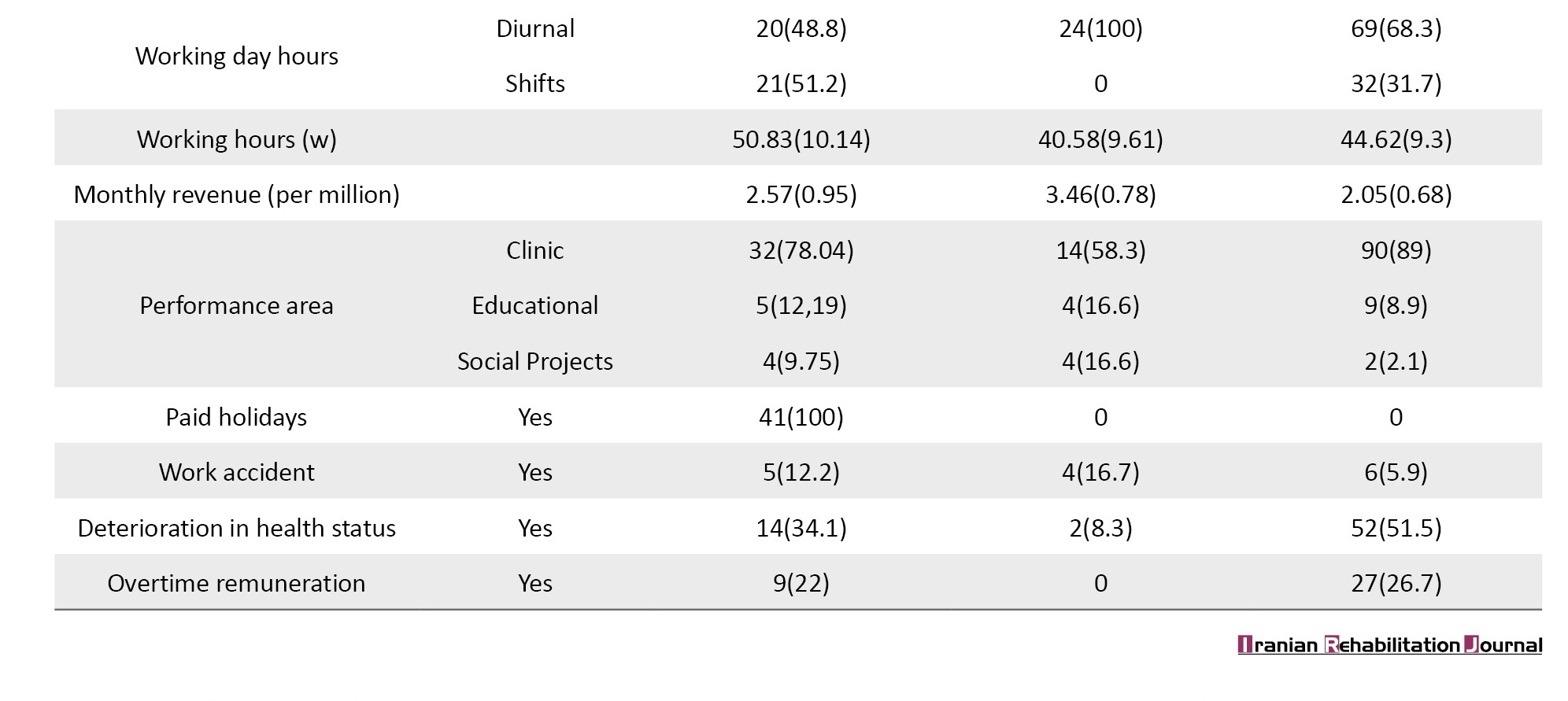

Approximately 1000 rehabilitation professionals were contacted via email. Of these, 250 responded to the invitation. Seventy-eight were excluded because they either declined to participate, were not currently working in rehabilitation, or were not practicing in Colombia. The final sample included 172 participants. Initially, participants self-reported their type of contract: 47 indicated an employment contract, and 125 reported an independent contract. Subsequently, the questionnaire based on the Colombian Substantive Labor Code was applied to determine the presence of an emerging contract. The 47 participants in the employment group fulfilled the legal criteria for such contracts. However, only 24 of the 125 individuals with independent contracts met the requirements to remain in this category. The remaining 101 professionals (80.8% of those reporting independent contracts) met the legal conditions of a real employment relationship and were therefore reclassified into the emerging contract group. This group constituted 58% of the total population (Table 1).

Regarding the demographic and professional profiles, most participants were women, with a higher percentage of single individuals in the employment and emerging contract groups. Most of the reported cases belonged to a medium socioeconomic stratum. A total of 78 were physiotherapists, 35 occupational therapists, and 53 speech therapists. Among the entire group, 48% had postgraduate training, mainly at the specialization level (64%), and most professionals worked in clinical care (79%) (Table 1).

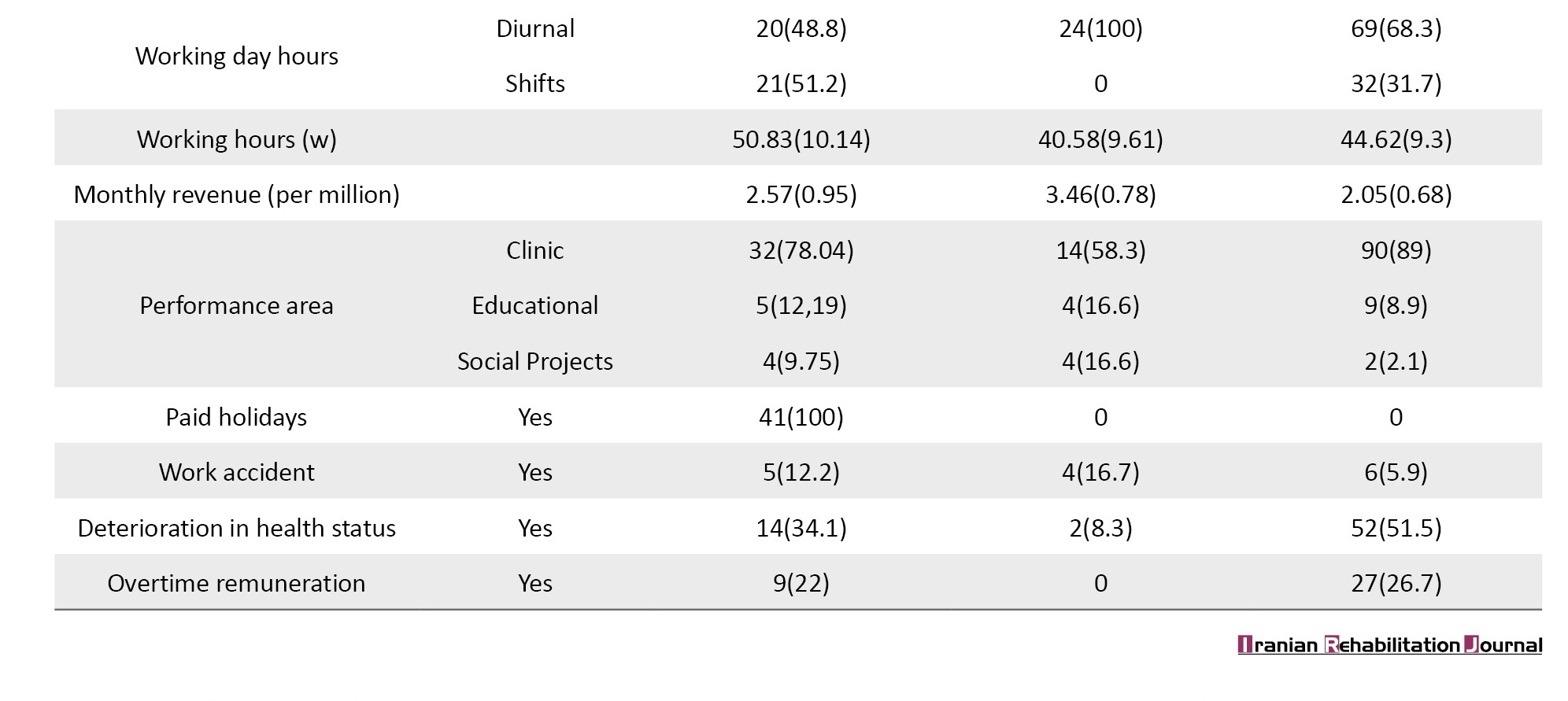

Regarding QoL, participants scored lowest in the categories of personal development (21.86±5.91) and FTM (11.88±4.17), with the global mean score being 202.8±42.75.

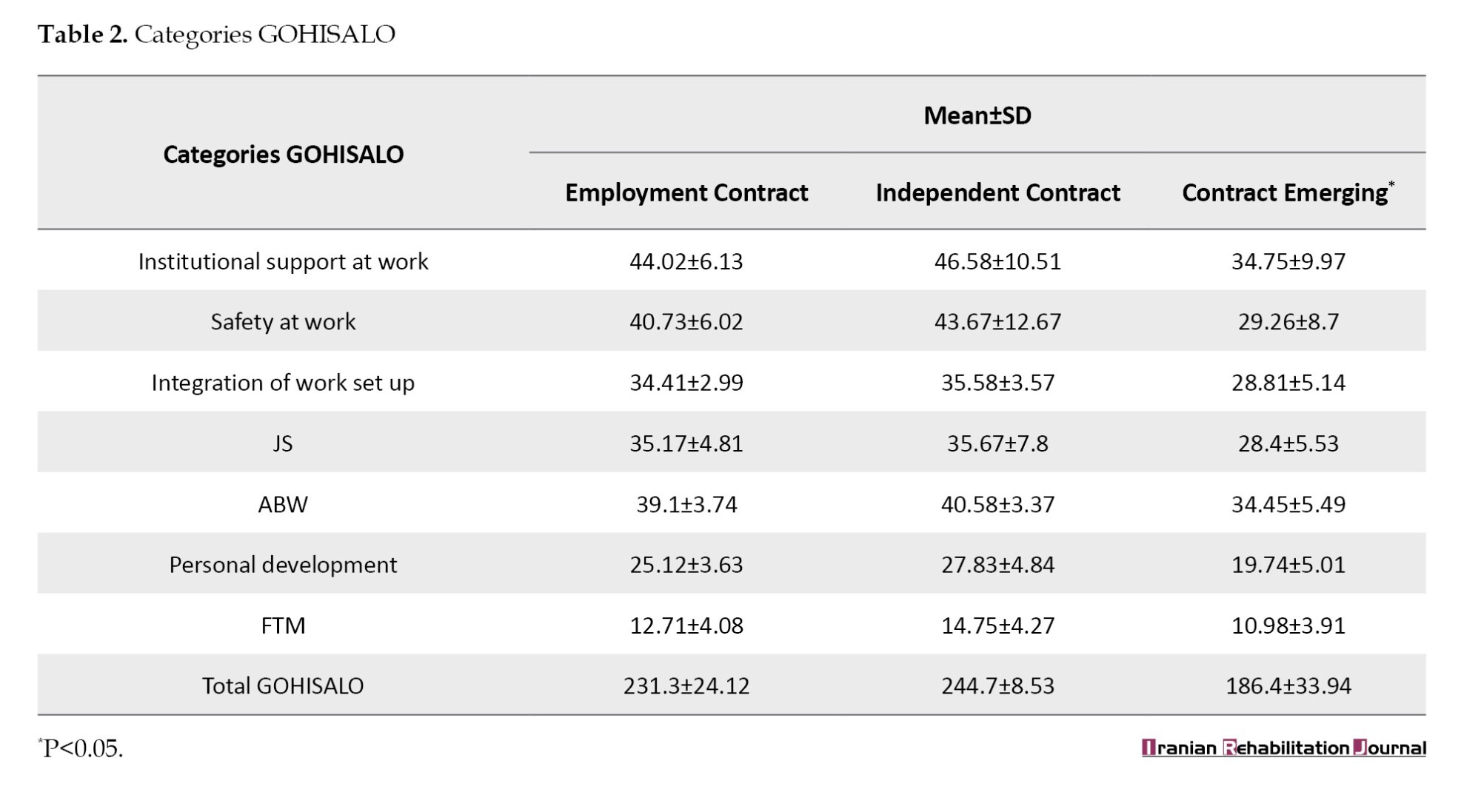

Table 2 presents the group comparisons: the emerging contract group consistently scored lowest across all GOHISALO dimensions. Notably, in dimensions such as personal development and FTM, the independent contract group obtained higher scores than the employment contract group, likely due to greater autonomy in scheduling and perceived control over professional growth. For example, in FTM, the independent contract group scored 14.75, versus 12.71 for the employment group and 10.98 for the emerging contract group. This was the only domain in which the independent group outperformed the employment group.

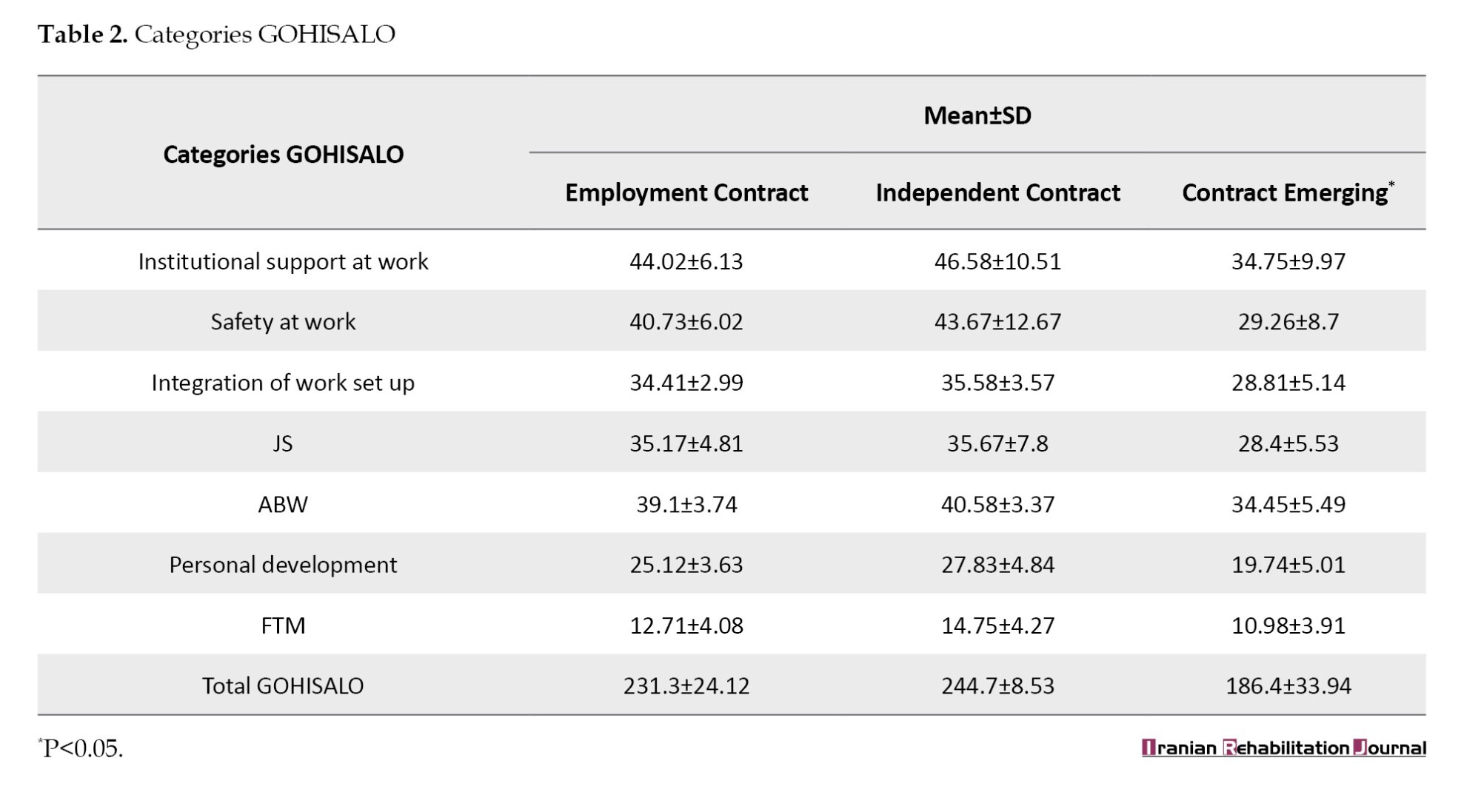

Analysis of T-scores showed consistently high satisfaction with “ISW” across all contract types. For “JS,” more than 70% of participants with employment or independent contracts reported high satisfaction, while over half of those with emerging contracts reported medium satisfaction. In “IW,” satisfaction was predominantly medium in the employment contract group, high in the independent group, and low in the emerging group. Across all groups, most participants reported low satisfaction in “JS.” For “well-being through work and personal development,” employment and independent contracts were mainly at medium to high levels, whereas emerging contracts concentrated in the low range; the same pattern was observed for “FTM” (Table 3).

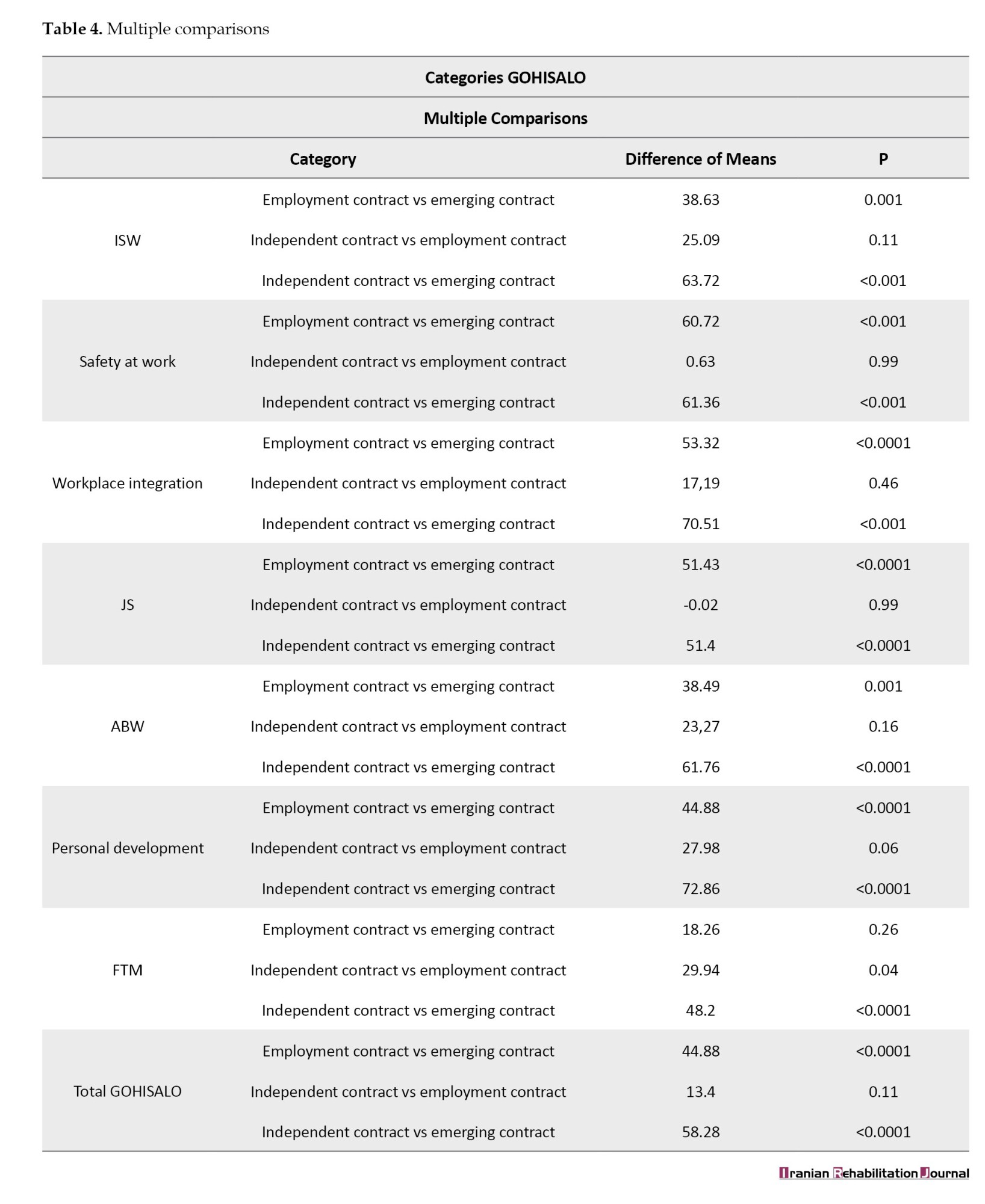

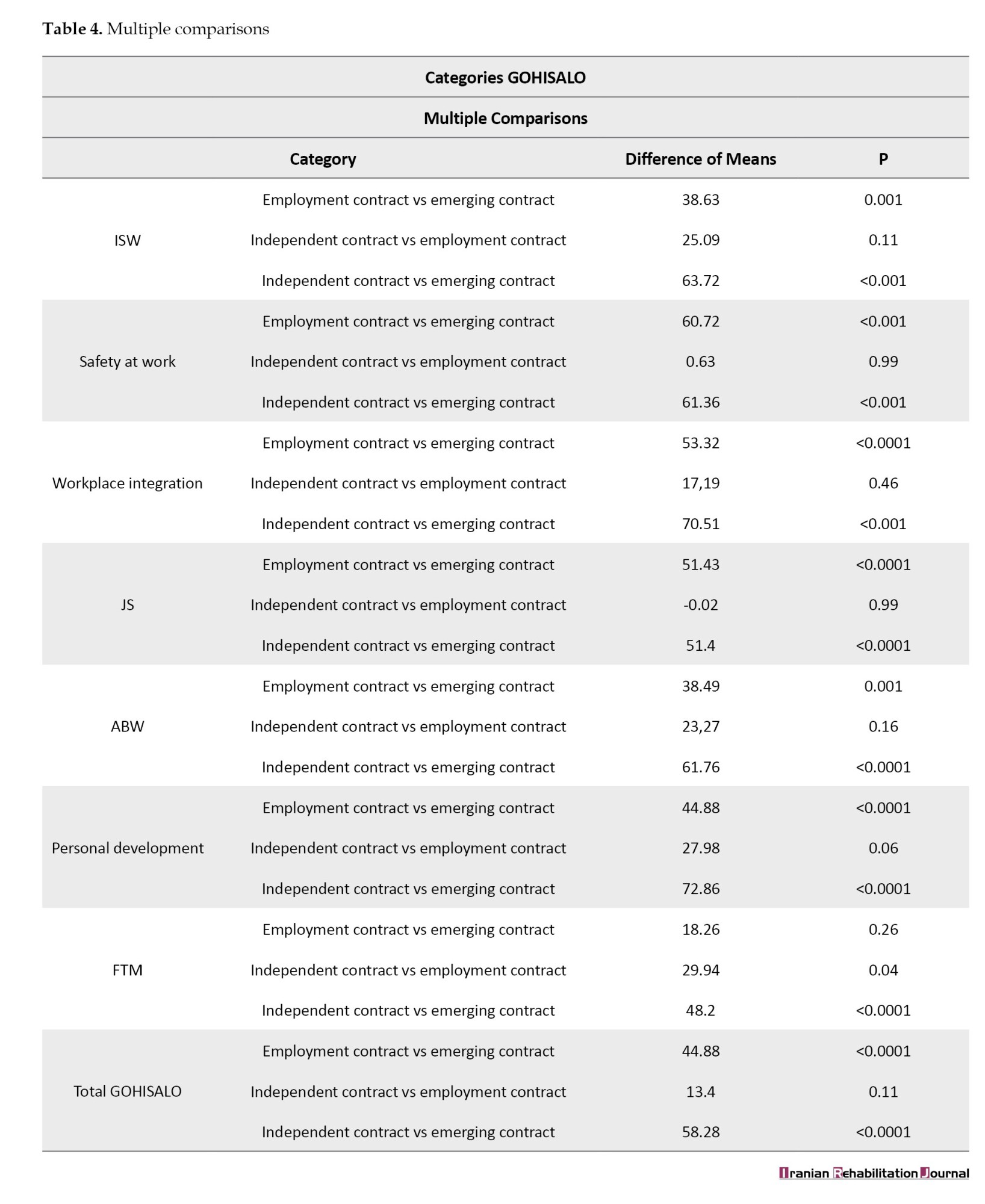

Table 4 presents the post-hoc analysis of variance (ANOVA) analysis. The emerging contract group consistently showed significantly lower scores than the other two groups (all P<0.001). In contrast, employment and independent contracts were statistically similar across most dimensions, except for FTM, where independent workers reported higher satisfaction (P=0.04). Although the study was primarily quantitative, open-ended comments from participants with emerging contracts highlighted dissatisfaction due to a lack of recognition, absence of benefits, and feeling treated as disposable labor, suggesting avenues for future qualitative research.

Discussion

The findings of this study, conducted among rehabilitation professionals, revealed that job instability extends beyond temporary or intermittent employment. In many cases, contracts for work or labor treat professionals as workers only in terms of obligations, not rights. The emerging contract reflects this reality: It combines the duties of an employment contract with the limited rights of service providers, highlighting job precariousness. It is essential to emphasize that these findings demonstrate associations rather than causal relationships, given the study’s cross-sectional design.

Precarious work, characterized by job insecurity, low wages, and unstable working hours, has become increasingly common in modern labour markets. This type of work arrangement raises concerns about its impact on workers’ QoL, including their physical and mental health, well-being, and overall life satisfaction [4]. The selection of GOHISALO questionnaire dimensions enabled a multifaceted characterization of quality of work life, facilitating the comparison of contractual stability with perceptions of support, professional growth, and work-related well-being. In our study, the emerging contract group scored significantly lower than the employment and independent groups, illustrating this impact’s breadth.

In the health sector, jobs have traditionally been secure. However, over the past 30 years, disparities in pay and working conditions have grown between these professionals and other health sector employees, whose jobs are part-time, temporary, contract, and non-:union:ized [15]. This situation is closely linked to higher levels of work-related stress, psychological distress, and mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety. This situation is especially worrying for young adults and migrant workers, who are particularly vulnerable to mental health problems [16].

This job insecurity, associated with emerging contractual modalities, generates employment conditions that are often intermittent, short-term, and unpredictable. These arrangements frequently lack continuity, stability, and social benefits, exposing professionals to constant uncertainty regarding their work and income [17].

It can be expected that workers in precarious employment experience more days of poor physical health and greater limitations in their daily activities due to health issues. Such job insecurity might also be associated with lower QoL and overall well-being, including poor sleep quality and persistent unhappiness. Additionally, unstable work schedules can contribute significantly to work-life conflict, undermining workers’ well-being [18].

Economic insecurity resulting from precarious employment impacts the worker’s life trajectories, where some face increasing precariousness, while others manage to remain protected thanks to previous financial security [19-21]. Finally, the negative effects of precarious work are exacerbated by broader socio-economic factors, such as a lack of social security, poor working conditions, and inadequate labour market policies. These elements create an environment that further aggravates the situation of workers in precarious jobs, perpetuating cycles of vulnerability and discontent [16, 22].

In our study, people with a contract for the provision of services had the highest mean age; however, the comparison results between groups were similar. This can be compared with previous studies in which most participants were speech therapists younger than 35 years old [23]. Although no multivariate statistical analyses were conducted to examine the specific influence of sociodemographic variables, such as age, marital status, number of children, or level of education on QoL outcomes, these characteristics were described in detail across groups (Table 1). Their distribution was considered during the interpretation of results, especially when exploring differences in areas such as JS, personal development, and FTM. Future studies should incorporate analytical models to examine potential interactions between contract type and personal or professional characteristics.

Regarding wage income, the idea persists among health professionals that income has decreased significantly in recent years. As suggested in previous studies [24], the implementation of current labor regulations has coincided with a trend toward increased job precariousness, particularly for those without direct contracts with institutions. Wage disparities have widened, working hours have intensified, and underemployment has emerged. Therefore, unpaid overtime and income levels per million pesos were also considered relevant indicators in this study.

Regarding QoL, the results show that professionals are moderately satisfied in most domains, similar to what has been reported in previous studies in nursing. However, significant variations are observed depending on the type of contract.

In the institutional support domain, most workers reported high levels of satisfaction. Satisfaction patterns varied by contract type and partially coincided with previous studies in Colombia [25, 26]. Regarding JS and integration, mean levels of satisfaction were identified, except independent contract group, which showed higher levels of satisfaction compared to previous studies in nursing by contract type [27].

The emerging and direct contract groups showed low satisfaction in domains, such as personal development and FTM, in contrast to the independent contract group, which reached high levels in almost all items. These findings partially coincide with international studies that report widespread dissatisfaction among health workers, particularly in job promotion and well-being areas [28, 29].

Overall, the independent contract group had the best QWL, while professionals with emerging contracts had the lowest score. These results reflect that job stability is associated with higher satisfaction levels, as has also been pointed out by other regional studies [27]. Job insecurity, lack of social benefits, and the need to take on additional jobs could disproportionately affect professionals under emerging contracts, potentially impacting their productivity and undermining compliance with international decent work standards outlined by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) [30].

Inequalities in healthcare workers also negatively impact equitable access to primary healthcare and specialized services. Inequalities in education, working conditions, and compensation are central to this crisis. However, labor policies often ignore disparities linked to contract type and JS, making it difficult to assess and address them. Ensuring a fair distribution of services and resources is essential to achieving health equity [31].

The situation in which a worker assumes duties inherent to an employment contract but is linked to a service provider exemplifies job insecurity. This model restricts access to social security, benefits, job stability, and :union: representation, reinforcing structural inequalities and exposing workers to greater vulnerability [32].

In economic terms, this contract may negatively affect society by allowing companies to avoid paying mandatory social security contributions, thereby increasing the burden on public health and social assistance systems. In addition, the absence of economic benefits affects workers’ purchasing power, which decreases household consumption and slows economic growth. This phenomenon also widens social gaps by limiting access to basic services such as health and pensions, increasing pressure on state assistance programs [33].

In this context, precarious employment violates fundamental principles of labour justice, such as those promoted by the ILO [33], and weakens economic and social cohesion by perpetuating structural inequalities and disrupting welfare systems. It is essential to move towards policies that promote the protection of labour rights to reduce social and economic inequalities.

One limitation of this study is that classification by contractual modality may not fully capture the complexity of labor relationships, especially in borderline cases. However, using the term emerging contract allowed us to include atypical but legally relevant situations. We also acknowledge the absence of multivariate analyses to control for sociodemographic variables such as age, marital status, and education, which may influence QoL. This decision was intentional, as the study was designed primarily with a descriptive and exploratory scope. In addition, the recruitment was non-random, and responses were based on self-reported questionnaires, introducing potential bias. Finally, the cross-sectional design precluded establishing temporal or causal inferences. A detailed economic analysis was also not conducted due to limitations in consistent post-pandemic data.

Nevertheless, these limitations are not considered to undermine the main contribution of this research, as the study’s descriptive and exploratory design aimed to provide an initial characterization of QoL across different contracts. The focus was on identifying patterns and associations rather than establishing causality or generalizable prevalence, meaning that despite these constraints, the findings offer valuable insights into the experiences of rehabilitation professionals and can guide future, more controlled studies.

Conclusion

The research shows a marked inequality between professionals depending on their contract type. While those with traditional contracts enjoy stability and better economic conditions, those with emerging contracts face precariousness, work overload, and a lack of compensation for overtime. The absence of effective regulation perpetuates this exploitation, affecting workers’ QoL and the health sector’s efficiency. Job instability negatively impacts employee satisfaction and well-being, especially mental health, which deteriorates the quality of services provided. Improving working conditions would benefit workers and society, guaranteeing more efficient and higher-quality care.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia (Code: 017016). It followed the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE). All participants entered voluntarily and signed informed consent.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, investigation, and project administration: Diana Guerrero-Jaramillo and Vicente Benavides-Cordoba; Validation, data curation, formal analysis, writing, and visualization: All authors;

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants who agreed to participate in this study.

References

Employment growth in the health sector can generate multiple benefits: It improves health outcomes, drives economic growth, and promotes equity, especially for women and young people. According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO), 40 million health jobs are expected by 2030, mainly in middle- and high-income countries. However, in low-income countries, defined by the World Bank as those with a gross national income per capita of 1,135 USD or less, there are two problems: A shortage of health workers and the precariousness of the jobs provided. Therefore, the priority is not only to create new jobs but also to promote formality and equity among workers in the same area [1].

The different types of contractual modalities that began to emerge as a result of the phenomenon of globalization have led to a greater number of workers with unstable jobs and a significant decrease in their income, making it difficult for them to maintain a dignified standard of living and affecting their families and social environments [2, 3].

Work precariousness resulting from new forms of employment generates stress in workers not only due to pressures within the workplace, but also because such precariousness prevents them from achieving a decent quality of life (QoL), which allows them to meet human needs in terms of acquiring goods and services for themselves and their families, as well as time for themselves and their families as well as for self-care [4]. This situation, particularly among healthcare workers, has clinical implications due to the stress generated, such as cardiovascular diseases [5], depression, anxiety, and other mental health disorders [6], and changes in social and health-related behaviors [7], and absenteeism [8].

In Europe, it has been found that the desire to leave the profession increases when workers perceive a high workload, insufficient rewards, and rising job demands [9]. In Latin America, a relationship has been identified between low motivation and labor conflicts, triggered by work overload and insufficient resources for work operations, as factors that contribute to professional burnout in health workers [10].

Quality of working life (QWL) refers to employees’ attitudes towards their work, including development, talent utilization, compensation, and well-being. It is linked to job satisfaction (JS) and perceptions of justice in the organization. Improving QWL and organizational performance is essential, especially in the healthcare sector, where productivity must be increased due to staff shortages. Nursing managers can help meet these challenges by improving human resource management and planning [11].

In Colombia, companies hire workers through different contracts. Some guarantee stability and legal benefits, while others are limited to the payment for a service. In practice, situations often arise where workers perform the functions of a formal employment relationship but are hired under service contracts, a condition known as a real or “emerging contract,” defined in this study as a modality in which workers assume the duties of employees without access to the corresponding labor rights or benefits [12].

The present study aims to investigate whether differences in the type of contract influence QOL, considering both workers with formal contracts and those who operate under real contracts, which are all professionals in human rehabilitation. Through this analysis, we aimed to identify whether the working conditions associated with different types of contracts significantly impact employee well-being and satisfaction. While similar studies exist in Europe and Latin America, Colombia presents a distinct context due to widespread informal labor practices in the health sector. This research is necessary to provide local evidence, identify the impact of emerging contracts, and inform labor policy within Colombia’s specific legal and social frameworks.

Materials and Methods

This was an observational cross-sectional study that included professionals in physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy who worked in health, education, and social projects and had at least one year of work experience in the field. The one-year minimum was established to ensure that participants had sufficient exposure to their contractual conditions and institutional environment, allowing for a meaningful assessment of how these factors impacted their QWL. The decision to focus on these specific rehabilitation disciplines was based on their prevalence in the Colombian labor market and their substantial representation in public and private institutions. Including a broader spectrum of specialties may have diluted the focus and statistical power of the analysis. The questionnaires were applied in person using printed forms under the supervision of the researchers between January 2018 and February 2021. The study was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the Universidad del Valle (Colombia); and followed the STROBE guidelines [13]. All participants entered voluntarily and signed informed consent.

This study focused on three types of contracts common in Colombia:

1) Employment contract guarantees labor rights such as social security, paid leave, and job stability; 2) Independent contract: Where professionals are considered service providers without subordination, and, therefore, do not receive benefits like paid leave or severance; 3) Emerging contract, a term used in this study to classify individuals who, while officially hired as independent contractors, fulfilled all the conditions of a real employment relationship. These include subordination, company-assigned tasks, and periodic remuneration, as defined in Articles 23-26 of the Colombian Substantive Labor Code.

Although Colombia also uses other hiring modalities, such as fixed-term, temporary agency contracts, and contracts by commission, this study focused on the three types mentioned above because they are the most frequently used in the rehabilitation sector. These types were of particular interest due to their ambiguous nature and the potential for labor rights violations in emerging contracts.

Sampling combined probabilistic and non-probabilistic methods. Initially, a required sample size of 187 participants was calculated, derived from a population frame of 3845 professionals registered in the territorial entity between 1994 and 2017, with a precision of 95%, a significance level of 5% and an error of 7%. Due to access limitations, recruitment followed a snowball strategy. This method began with participants selected from predefined criteria, who received the questionnaires and were instructed to refer others who met the same inclusion criteria. This strategy allowed us to reach the projected sample size by progressively expanding the network of participants through recommendations. To ensure consistency and accuracy in data collection, all questionnaires were self-administered under supervision when possible, or completed remotely under clear instructions sent by email or messaging platforms. Participants were instructed to complete the instruments in a single session in a quiet environment. A detailed explanation of the objectives and instructions was provided before completion, and contact was maintained for clarification if needed. Incomplete or inconsistent responses were reviewed and, when necessary, validated directly with respondents.

We collected sociodemographic and labor information from all participants and classified them based on their employment contracts. This classification was based on the information provided by each professional, specifically those who self-identified as having either an employment or an independent contract. To identify whether the participant had an emerging form of contract, a questionnaire on the budget of a real contract was applied.

This questionnaire was designed based on articles 23-26 of the Colombian Substantive Labor Code. The interview was structured around the three key elements required to establish an employment relationship: Alignment with the company’s core mission, subordination to an employer, and receipt of regular wages. Responses were assessed using a checklist to ensure consistency across participants. The tool was validated by a labor law judge in Colombia with expertise in employment classification to ensure rigorous application of legal criteria. Additionally, two psychologists with experience in occupational health reviewed the instrument to ensure clarity, coherence, and relevance of the items.

Participants who met all three items (core mission, subordination and regular wages) were included in the emerging contract group. The “quality of life at work-GOHISALO” (CVT-GOHISALO) questionnaire was then applied. This instrument was designed to comprehensively measure the quality of work life, addressing various aspects of the work environment that may affect workers’ well-being. The CVT-GOHISALO has demonstrated solid psychometric properties, with a reported Cronbach’s α of 0.91 for the overall instrument and values above 0.7 for each dimension. Its construct validity was supported through factorial analysis, and it has been widely used in occupational health research in Latin America, particularly in Colombia and Mexico. This instrument assesses seven key dimensions: Working conditions, job stress, relationship with coworkers, satisfaction with salary, workload, training and professional development, and work-life balance. It consists of a Likert-type scale with 74 items in seven dimensions, giving a value from 0 to 4, where zero is not satisfied and four is completely satisfied. The score is represented in percentile values; the 50th percentile represents the average with a deviation of 10. Thus, a T<40 was considered low, between 40 and 60 medium, and more than 60 was considered a high score [14].

To facilitate comparative analysis between employment groups, each of the seven dimensions assessed by the GOHISALO, according to the authors [14] was categorized into three levels: Low (T-score<40), medium (T-score 40–60), and high (T-score >60). These categories allowed us to analyze the distribution of perceived QoL using frequency data.

The dimensions evaluated were institutional support for work (ISW), job security, integration into the workplace (IW), Job satisfaction, well-being achieved through work (ABW), personal development of the worker, free time management (FTM), and the total score. Once scored, it was assessed individually and then generally, highlighting the most critical dimensions that generated a perception of dissatisfaction on the part of the worker.

Qualitative variables, such as sex, profession, marital status, contractual modality, and type of institution, were presented as frequencies and percentages. Quantitative variables, including age and total and dimensional scores of the GOHISALO questionnaire, are presented as Mean±SD. Prior to performing inferential statistics, normality tests were applied using the D’Agostino-Pearson test. For variables with abnormal distribution, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used; otherwise, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied for normally distributed variables. Group comparisons of proportions obtained from the CVT-GOHISALO T score were conducted using M×N tables and the Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test. All analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 20.

Results

Approximately 1000 rehabilitation professionals were contacted via email. Of these, 250 responded to the invitation. Seventy-eight were excluded because they either declined to participate, were not currently working in rehabilitation, or were not practicing in Colombia. The final sample included 172 participants. Initially, participants self-reported their type of contract: 47 indicated an employment contract, and 125 reported an independent contract. Subsequently, the questionnaire based on the Colombian Substantive Labor Code was applied to determine the presence of an emerging contract. The 47 participants in the employment group fulfilled the legal criteria for such contracts. However, only 24 of the 125 individuals with independent contracts met the requirements to remain in this category. The remaining 101 professionals (80.8% of those reporting independent contracts) met the legal conditions of a real employment relationship and were therefore reclassified into the emerging contract group. This group constituted 58% of the total population (Table 1).

Regarding the demographic and professional profiles, most participants were women, with a higher percentage of single individuals in the employment and emerging contract groups. Most of the reported cases belonged to a medium socioeconomic stratum. A total of 78 were physiotherapists, 35 occupational therapists, and 53 speech therapists. Among the entire group, 48% had postgraduate training, mainly at the specialization level (64%), and most professionals worked in clinical care (79%) (Table 1).

Regarding QoL, participants scored lowest in the categories of personal development (21.86±5.91) and FTM (11.88±4.17), with the global mean score being 202.8±42.75.

Table 2 presents the group comparisons: the emerging contract group consistently scored lowest across all GOHISALO dimensions. Notably, in dimensions such as personal development and FTM, the independent contract group obtained higher scores than the employment contract group, likely due to greater autonomy in scheduling and perceived control over professional growth. For example, in FTM, the independent contract group scored 14.75, versus 12.71 for the employment group and 10.98 for the emerging contract group. This was the only domain in which the independent group outperformed the employment group.

Analysis of T-scores showed consistently high satisfaction with “ISW” across all contract types. For “JS,” more than 70% of participants with employment or independent contracts reported high satisfaction, while over half of those with emerging contracts reported medium satisfaction. In “IW,” satisfaction was predominantly medium in the employment contract group, high in the independent group, and low in the emerging group. Across all groups, most participants reported low satisfaction in “JS.” For “well-being through work and personal development,” employment and independent contracts were mainly at medium to high levels, whereas emerging contracts concentrated in the low range; the same pattern was observed for “FTM” (Table 3).

Table 4 presents the post-hoc analysis of variance (ANOVA) analysis. The emerging contract group consistently showed significantly lower scores than the other two groups (all P<0.001). In contrast, employment and independent contracts were statistically similar across most dimensions, except for FTM, where independent workers reported higher satisfaction (P=0.04). Although the study was primarily quantitative, open-ended comments from participants with emerging contracts highlighted dissatisfaction due to a lack of recognition, absence of benefits, and feeling treated as disposable labor, suggesting avenues for future qualitative research.

Discussion

The findings of this study, conducted among rehabilitation professionals, revealed that job instability extends beyond temporary or intermittent employment. In many cases, contracts for work or labor treat professionals as workers only in terms of obligations, not rights. The emerging contract reflects this reality: It combines the duties of an employment contract with the limited rights of service providers, highlighting job precariousness. It is essential to emphasize that these findings demonstrate associations rather than causal relationships, given the study’s cross-sectional design.

Precarious work, characterized by job insecurity, low wages, and unstable working hours, has become increasingly common in modern labour markets. This type of work arrangement raises concerns about its impact on workers’ QoL, including their physical and mental health, well-being, and overall life satisfaction [4]. The selection of GOHISALO questionnaire dimensions enabled a multifaceted characterization of quality of work life, facilitating the comparison of contractual stability with perceptions of support, professional growth, and work-related well-being. In our study, the emerging contract group scored significantly lower than the employment and independent groups, illustrating this impact’s breadth.

In the health sector, jobs have traditionally been secure. However, over the past 30 years, disparities in pay and working conditions have grown between these professionals and other health sector employees, whose jobs are part-time, temporary, contract, and non-:union:ized [15]. This situation is closely linked to higher levels of work-related stress, psychological distress, and mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety. This situation is especially worrying for young adults and migrant workers, who are particularly vulnerable to mental health problems [16].

This job insecurity, associated with emerging contractual modalities, generates employment conditions that are often intermittent, short-term, and unpredictable. These arrangements frequently lack continuity, stability, and social benefits, exposing professionals to constant uncertainty regarding their work and income [17].

It can be expected that workers in precarious employment experience more days of poor physical health and greater limitations in their daily activities due to health issues. Such job insecurity might also be associated with lower QoL and overall well-being, including poor sleep quality and persistent unhappiness. Additionally, unstable work schedules can contribute significantly to work-life conflict, undermining workers’ well-being [18].

Economic insecurity resulting from precarious employment impacts the worker’s life trajectories, where some face increasing precariousness, while others manage to remain protected thanks to previous financial security [19-21]. Finally, the negative effects of precarious work are exacerbated by broader socio-economic factors, such as a lack of social security, poor working conditions, and inadequate labour market policies. These elements create an environment that further aggravates the situation of workers in precarious jobs, perpetuating cycles of vulnerability and discontent [16, 22].

In our study, people with a contract for the provision of services had the highest mean age; however, the comparison results between groups were similar. This can be compared with previous studies in which most participants were speech therapists younger than 35 years old [23]. Although no multivariate statistical analyses were conducted to examine the specific influence of sociodemographic variables, such as age, marital status, number of children, or level of education on QoL outcomes, these characteristics were described in detail across groups (Table 1). Their distribution was considered during the interpretation of results, especially when exploring differences in areas such as JS, personal development, and FTM. Future studies should incorporate analytical models to examine potential interactions between contract type and personal or professional characteristics.

Regarding wage income, the idea persists among health professionals that income has decreased significantly in recent years. As suggested in previous studies [24], the implementation of current labor regulations has coincided with a trend toward increased job precariousness, particularly for those without direct contracts with institutions. Wage disparities have widened, working hours have intensified, and underemployment has emerged. Therefore, unpaid overtime and income levels per million pesos were also considered relevant indicators in this study.

Regarding QoL, the results show that professionals are moderately satisfied in most domains, similar to what has been reported in previous studies in nursing. However, significant variations are observed depending on the type of contract.

In the institutional support domain, most workers reported high levels of satisfaction. Satisfaction patterns varied by contract type and partially coincided with previous studies in Colombia [25, 26]. Regarding JS and integration, mean levels of satisfaction were identified, except independent contract group, which showed higher levels of satisfaction compared to previous studies in nursing by contract type [27].

The emerging and direct contract groups showed low satisfaction in domains, such as personal development and FTM, in contrast to the independent contract group, which reached high levels in almost all items. These findings partially coincide with international studies that report widespread dissatisfaction among health workers, particularly in job promotion and well-being areas [28, 29].

Overall, the independent contract group had the best QWL, while professionals with emerging contracts had the lowest score. These results reflect that job stability is associated with higher satisfaction levels, as has also been pointed out by other regional studies [27]. Job insecurity, lack of social benefits, and the need to take on additional jobs could disproportionately affect professionals under emerging contracts, potentially impacting their productivity and undermining compliance with international decent work standards outlined by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) [30].

Inequalities in healthcare workers also negatively impact equitable access to primary healthcare and specialized services. Inequalities in education, working conditions, and compensation are central to this crisis. However, labor policies often ignore disparities linked to contract type and JS, making it difficult to assess and address them. Ensuring a fair distribution of services and resources is essential to achieving health equity [31].

The situation in which a worker assumes duties inherent to an employment contract but is linked to a service provider exemplifies job insecurity. This model restricts access to social security, benefits, job stability, and :union: representation, reinforcing structural inequalities and exposing workers to greater vulnerability [32].

In economic terms, this contract may negatively affect society by allowing companies to avoid paying mandatory social security contributions, thereby increasing the burden on public health and social assistance systems. In addition, the absence of economic benefits affects workers’ purchasing power, which decreases household consumption and slows economic growth. This phenomenon also widens social gaps by limiting access to basic services such as health and pensions, increasing pressure on state assistance programs [33].

In this context, precarious employment violates fundamental principles of labour justice, such as those promoted by the ILO [33], and weakens economic and social cohesion by perpetuating structural inequalities and disrupting welfare systems. It is essential to move towards policies that promote the protection of labour rights to reduce social and economic inequalities.

One limitation of this study is that classification by contractual modality may not fully capture the complexity of labor relationships, especially in borderline cases. However, using the term emerging contract allowed us to include atypical but legally relevant situations. We also acknowledge the absence of multivariate analyses to control for sociodemographic variables such as age, marital status, and education, which may influence QoL. This decision was intentional, as the study was designed primarily with a descriptive and exploratory scope. In addition, the recruitment was non-random, and responses were based on self-reported questionnaires, introducing potential bias. Finally, the cross-sectional design precluded establishing temporal or causal inferences. A detailed economic analysis was also not conducted due to limitations in consistent post-pandemic data.

Nevertheless, these limitations are not considered to undermine the main contribution of this research, as the study’s descriptive and exploratory design aimed to provide an initial characterization of QoL across different contracts. The focus was on identifying patterns and associations rather than establishing causality or generalizable prevalence, meaning that despite these constraints, the findings offer valuable insights into the experiences of rehabilitation professionals and can guide future, more controlled studies.

Conclusion

The research shows a marked inequality between professionals depending on their contract type. While those with traditional contracts enjoy stability and better economic conditions, those with emerging contracts face precariousness, work overload, and a lack of compensation for overtime. The absence of effective regulation perpetuates this exploitation, affecting workers’ QoL and the health sector’s efficiency. Job instability negatively impacts employee satisfaction and well-being, especially mental health, which deteriorates the quality of services provided. Improving working conditions would benefit workers and society, guaranteeing more efficient and higher-quality care.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia (Code: 017016). It followed the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE). All participants entered voluntarily and signed informed consent.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, investigation, and project administration: Diana Guerrero-Jaramillo and Vicente Benavides-Cordoba; Validation, data curation, formal analysis, writing, and visualization: All authors;

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants who agreed to participate in this study.

References

- UN Commission: New investments in global health workforce will create jobs and drive economic growth [Internet]. 2025 [Updated 2025 June 18]. Available from: [Link]

- Mushtaq M, Ahmed S, Fahlevi M, Aljuaid M, Saniuk S. Globalization and employment nexus: Moderating role of human capital. Plos One. 2022; 17(10):e0276431. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0276431] [PMID]

- Davidson C, Heyman F, Matusz S, Sjöholm F, Zhu SC. Globalization, the jobs ladder and economic mobility. European Economic Review. 2020; 127:103444. [DOI:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2020.103444]

- Bhattacharya A, Ray T. Precarious work, job stress, and health-related quality of life. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2021; 64(4):310-9. [DOI:10.1002/ajim.23223] [PMID]

- Matilla-Santander N, Muntaner C, Kreshpaj B, Gunn V, Jonsson J, Kokkinen L,et al. Trajectories of precarious employment and the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke among middle-aged workers in Sweden: A register-based cohort study. The Lancet Regional Health. Europe. 2022; 15:100314. [DOI:10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100314] [PMID]

- Irvine A, Rose N. How does precarious employment affect mental health? A scoping review and thematic synthesis of qualitative evidence from western economies. Work, Employment and Society. 2024; 38(2):418-41. [DOI:10.1177/09500170221128698]

- Perri M, O'Campo P, Gill P, Gunn V, Ma RW, Buhariwala P, et al. Precarious work on the rise. BMC Public Health. 2024; 24(1):2074. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-024-19363-3] [PMID]

- Oke A, Braithwaite P, Antai D. Sickness absence and precarious employment: A comparative cross-national study of denmark, finland, sweden, and norway. The International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2016; 7(3):125-47. [DOI:10.15171/ijoem.2016.713] [PMID]

- Montano D, Kuchenbaur M, Geissler H, Peter R. Working conditions of healthcare workers and clients' satisfaction with care: Study protocol and baseline results of a cluster-randomised workplace intervention. BMC Public Health. 2020; 20(1):1281. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-020-09290-4] [PMID]

- Parker CP, Baltes BB, Young SA, Huff JW, Altmann RA, Lacost HA, et al. Relationships between psychological climate perceptions and work outcomes: A meta-analytic review. The Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2003; 24(4):389-416. [DOI:10.1002/job.198]

- Kumar A, Bhat PS, Ryali S. Study of quality of life among health workers and psychosocial factors influencing it. Industrial Psychiatry Journal. 2018; 27(1):96-102. [DOI:10.4103/ipj.ipj_41_18] [PMID]

- Corte Constitucional de Colombia. T-366-23 [Internet]. [Updated 2024 November 25]. Available from: [Link]

- Cuschieri S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia. 2019; 13(Suppl 1):S31-4. [DOI:10.4103/sja.SJA_543_18] [PMID]

- González Baltazar R, Hidalgo Santacruz G, Salazar Estrada JG, Preciado Serrano ML. Elaboración y validación del instrumento para medir calidad de vida en el trabajo “CVT-GOHISALO”. Cienc Trab. 2010; 12(36):332–40. [Link]

- Pinto AD, Hapsari AP, Ho J, Meaney C, Avery L, Hassen N, et al. Precarious work among personal support workers in the Greater Toronto Area: A respondent-driven sampling study. CMAJ Open. 2022; 10(2):E527-38. [DOI:10.9778/cmajo.20210338] [PMID]

- Vancea M, Utzet M. How unemployment and precarious employment affect the health of young people: A scoping study on social determinants. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2017; 45(1):73-84. [DOI:10.1177/1403494816679555] [PMID]

- Collins H. Job security, precarious work, and freedom of contract. LSE Public Policy Review. 2024; 3(2):1-10. [DOI:10.31389/lseppr.98]

- Schneider D, Harknett K. Consequences of routine work-schedule instability for worker health and well-being. American Sociological Review. 2019; 84(1):82-114. [DOI:10.1177/0003122418823184] [PMID]

- Barnes T, Weller SA. Becoming precarious? Precarious work and life trajectories after retrenchment. Critical Sociology. 2020; 46(4-5):527-41. [DOI:10.1177/0896920519896822]

- Pyöriä P, Ojala S. Precarious work and intrinsic job quality: Evidence from Finland, 1984–2013. The Economic and Labour Relations Review. 2016; 27(3):349-67.[DOI:10.1177/1035304616659190]

- Barnes T. Pathways to precarity: Work, financial insecurity and wage dependency among Australia’s retrenched auto workers. Journal of Sociology. 2021; 57(2):443-63. [DOI:10.1177/1440783320925151]

- Bosmans K, Vignola EF, Álvarez-López V, Julià M, Ahonen EQ, Bolíbar M, et al. Experiences of insecurity among non-standard workers across different welfare states: A qualitative cross-country study. Social Science & Medicine. 2023; 327:115970. [DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.115970] [PMID]

- Lin Q, Lu J, Chen Z, Yan J, Wang H, Ouyang H, et al. A survey of speech-language-hearing therapists' career situation and challenges in Mainland China. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica. 2016; 68(1):10-5. [DOI:10.1159/000442284] [PMID]

- Florez Acosta JH, Atehortúa Becerra SC, Arenas Mejía AC. Las condiciones laborales de los profesionales de la salud a partir de la Ley 100 de 1993: Evolución y un estudio de caso para Medellín. Revista Gerencia y Políticas de Salud. 2009; 8(16):107-31. [Link]

- Vélez MA. Calidad de vida laboral en empleados temporales del Valle de Aburrá-Colombia. Revista Ciencias Estratégicas. 2010; 18(24):225-36. [Link]

- Suescún-Carrero S, Sarmiento G, Álvarez L, Lugo M. Calidad de vida laboral en trabajadores de una Empresa Social del Estado de Tunja, Colombia. Revista Médica de Risaralda. 2016; 22(1):14-7. [DOI:10.22517/25395203.13631]

- Zavala MO, Klinj TP, Carrillo KL. Quality of life in the workplace for nursing staff at public healthcare institutions. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem. 2016; 24:e2713. [DOI:10.1590/1518-8345.1149.2713] [PMID]

- Delgado García D, Inzulza González M, Delgado García F. Calidad de vida en el trabajo: Profesionales de la salud de clínica río blanco y centro de especialidades médicas. Medicina y seguridad del trabajo. 2012; 58(228):216-23. [DOI:10.4321/S0465-546X2012000300006]

- Díaz Corte C, Suárez Álvarez Ó, Fueyo Gutiérrez A, Mola Caballero de Rodas P, Rancaño García I, Sánchez Fernández AM, et al. [Professional quality of life in the clinical governance model of Asturias (Spain)]. Gaceta sanitaria. 2013; 27(6):502-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.gaceta.2013.01.012] [PMID]

- Kim HJ, Duffy RD, Allan BA. Profiles of decent work: General trends and group differences. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2021; 68(1):54-66. [DOI:10.1037/cou0000434] [PMID]

- Santric Milicevic M, Scotter CDP, Bruno-Tome A, Scheerens C, Ellington K. Healthcare workforce equity for health equity: An overview of its importance for the level of primary health care. The International journal of health planning and management. 2024; 39(3):945-55. [DOI:10.1002/hpm.3790] [PMID]

- Cuevas Valenzuela H. Precariedad, precariado y precarización: un comentario crítico desde américa latina a the precariat. The new dangerous class de guy standing. Polis 2015; 14(40):313-29. [DOI:10.4067/S0718-65682015000100015]

- La Organización Internacional del Trabajo. [Acerca de la OIT (Spanish)] [Internet]. 2025 [Updated 2025 November 11]. Available from: [Link]

Article type: Original Research Articles |

Subject:

Rehabilitation Management

Received: 2025/04/28 | Accepted: 2025/09/3 | Published: 2025/12/1

Received: 2025/04/28 | Accepted: 2025/09/3 | Published: 2025/12/1

Send email to the article author