Volume 23, Issue 3 (September 2025)

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2025, 23(3): 267-276 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.KMU.REC.1397.547

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rashedi V, Yazdani M, Borhaninejad V. Transcending Age: How Gerotranscendence Influences Life Satisfaction in Iranian Older Adults. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2025; 23 (3) :267-276

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2538-en.html

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2538-en.html

1- Department of Aging, Iranian Research Center on Aging, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran.

3- Neuroscience Research Center, Institute of Neuropharmacology, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran.

2- Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran.

3- Neuroscience Research Center, Institute of Neuropharmacology, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 526 kb]

(503 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1788 Views)

Full-Text: (258 Views)

Introduction

Today, alongside the growth of the older population worldwide, the social paradigm of aging is evolving [1]. As life expectancy rises, the proportion of older adults within the population grows accordingly, exposing them to significant shifts in their social networks, socioeconomic status, health conditions, and demographic circumstances [2]. In recent decades, numerous theoretical frameworks have been developed to conceptualize the process of healthy aging. Nonetheless, despite the assertions of certain models, a universally accepted definition supported by robust empirical evidence remains elusive [3]. In other words, many early studies on aging have been organized around the concept of adaptation and have focused on matching individuals with the loss of role to explain the concept of successful or normal aging [4, 5].

The theory of gerotranscendence, introduced by Lars Tornstam in 1989, is a pivotal framework for understanding the social and psychological dimensions of aging. This theory offers a transformative perspective on aging, portraying it as a lifelong developmental process [6]. Gerotranscendence encompasses three primary dimensions: The cosmic dimension, which reflects a deepened sense of connection with the universe and a redefined perception of the self as part of a larger whole; the coherence dimension, emphasizing life’s overall meaning and internal consistency; and the dimension of positive solitude, which highlights a reassessment of interpersonal relationships and the value of being alone [7, 8]. Tornstam described gerotranscendence as “a shift in meta-perspective from a materialistic and rational view of the world to a more cosmic and transcendent one,” a transformation often associated with enhanced life satisfaction [9]. The positive effect of many gerotranscendence-based interventions on life satisfaction levels has been confirmed in some studies, leading to a discussion on gerotranscendence and its potential to achieve higher life satisfaction levels [10, 11].

Life satisfaction in older adults is shaped by their ability to adapt to age-related changes and their subjective evaluation of their life circumstances, viewed through the lens of their cultural background, personal values, goals, expectations, and concerns [12, 13]. However, studies have reported contradictory findings on the level of life satisfaction among the elderly. Some studies have reported that older adults generally do not experience high levels of life satisfaction [14], while others have found moderate to high levels of life satisfaction in older adults [14, 15]. It appears that the elderly’s lifestyle has a significant impact on their satisfaction, and economic, social, and cultural factors also influence the level of life satisfaction [16]. However, life satisfaction is considered one of the most important indicators of mental health in old age, as it reflects a person’s attitude toward their life and can reflect their feelings about their past, present, or future [17, 18]. This indicator affects many aspects of the elderly’s life, such as self-care and health behaviors. Also, life dissatisfaction in older adults is associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality in men and cardiovascular mortality in women [19, 20].

The concept of gerotranscendence emphasizes how the experience and interpretation of aging can shift profoundly as individuals move from a materialistic, externally oriented view of life toward a more cosmic and introspective perspective [21]. This shift is heavily influenced by culture and social norms, meaning that gerotranscendence may manifest differently across societies with varying values, structures, and views on aging [22]. Gerontological research in Iran is still in its early stages, particularly in studies that integrate socio-psychological frameworks, such as gerotranscendence theory. A critical yet underexplored area is the potential influence of Islamic teachings, including the emphasis on spiritual maturation in late adulthood, veneration of elders, and eschatological beliefs on the developmental dimensions of gerotranscendence. Additionally, Iran’s collectivist sociocultural fabric, characterized by strong intergenerational cohesion and familial interdependence, may differentially facilitate or constrain specific facets of gerotranscendence, such as cosmic transcendence (i.e. a sense of unity with the universe) and ego integrity (i.e. reconciliation with one’s life narrative). There is a pressing need to expand such studies to better understand the aging experience within the Iranian sociocultural context. Research grounded in socio-psychological theories of aging can provide new insights into the psychological processes that shape well-being in later life, especially regarding key outcomes, such as life satisfaction. Among these theories, gerotranscendence stands out for its relevance to life satisfaction, a critical factor in the quality of life of older adults. Recognizing this gap, our study aims to investigate the relationship between gerotranscendence and life satisfaction among Iranian older adults, to contribute to a foundational understanding of how transcendent thinking can enrich the aging process and enhance life satisfaction in later years. This exploration not only advances academic knowledge but also has practical implications for developing culturally appropriate interventions that support the well-being of older adults.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional, population-based study employing an analytical-descriptive approach, targeting older adults aged >60 years. This study was conducted in Kerman City, Iran, over six months, from October 2022 to March 2023. Kerman is the capital city of Kerman Province, located 1 038 km from Tehran. It is the largest and most developed city in Kerman Province, and the most crucial city in southeastern Iran. According to the 2016 census, the population was 738 724. Kerman City, situated on the elevated periphery of the Lut Desert in south-central Iran, is encircled by mountain ranges and renowned for its rich historical and cultural legacy. The city is home to numerous ancient architectural landmarks, reflecting its deep-rooted heritage. Kerman’s economy is primarily sustained by agriculture and mining, with pistachio cultivation as a key economic driver. Administratively, the city is divided into four subdistricts and served by a single health center.

Populations and sample size

Participants were recruited from primary healthcare centers (PHCs) across Kerman, which are designated to implement the national program for integrated care of older adults. In total, 47 PHCs in the city are formally engaged in delivering this national initiative, providing services specifically tailored to the needs of the older adult population. The comprehensive elderly care program is an integrated and comprehensive elderly care program for physicians and non-physicians. Older adults are evaluated in terms of priority physical and mental illnesses based on the burden of illness and immunization, and this evaluation is supplemented by simple diagnostic and treatment methods. They will also receive health education to prevent disease.

The required sample size was calculated using a standard statistical formula for estimating population means, yielding a target of 200 participants. A two-stage cluster sampling approach was employed to ensure representativeness. First, 10 of the 47 PHCs were selected through probability proportional to size sampling, ensuring that larger PHCs had a higher chance of inclusion. Subsequently, within each selected PHC (cluster), 20 subjects were randomly chosen using a simple random sampling technique. This was achieved by assigning a unique random number to each patient record and systematically selecting participants based on a predetermined sampling interval. Most older adults covered by PHCs have a record; therefore, all participants were randomly selected from the available records. The inclusion criteria were: Age ≥60 years, Iranian citizenship, and willingness to provide informed consent to use data and participate. Each subject was then contacted at home through house visits, and additional data were collected, with participation requested. The questionnaires were self-administered by literate participants and interviewer-administered (gender-matched) for those who were illiterate.

Instrument

The instruments used to collect data included a form addressing socio-demographic variables, two validated questionnaires, and a question concerning self-reported health status with options of ‘good,’ ‘neither good nor bad,’ and ‘bad’.

Gerotranscendence was determined by using Tornstam’s short-form gerotranscendence scale (GS-S), which had 10 items in the form of a 4-point Likert-type scale (strongly agree=4 to strongly disagree=1; and reverse scoring for items 6 and 9). GS-S has three dimensions (sub-scales): The cosmic dimension (five items), the coherence dimension (two items), and the solitude dimension (three items). This questionnaire has been validated in the Iranian population. Cronbach’s α and coefficient omega of the scale were 0.72 and 0.82, respectively. Test, re-test reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC]=0.88, P<001), and the standard error of measurement was 1.16 (confidence interval [CI]=95%) [23].

Life satisfaction was determined using the life satisfaction index-Z (LSIZ). The original LSIZ contained 20 items. The LSIZ was proposed by Wood et al. using 13 of the 20 items from the LSIA [24]. The participants expressed their agreement or disagreement with the statements using a 3-point Likert scale (agree=2, disagree=1, and I do not know=0). The total score ranged from 0 to 26. A score between 0-12 indicated low Life Satisfaction, a score between 13-21 indicated moderate life satisfaction, and a score of 22 and above indicated high life satisfaction. This questionnaire has already been validated in the Iranian population, and Cronbach’s α of this scale was 0.79 [25].

Data analysis

Ultimately, 17 questionnaires were excluded due to incomplete or invalid responses, leaving 183 questionnaires for final analysis. Data were processed using SPSS software, version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). As the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test confirmed a normal distribution of the data, both descriptive and inferential statistical methods were employed for analysis.

Results

The study included 183 older adults, with a mean age of 66.7±7.14 years. The sample comprised 99 females (54.1%) and 127 married individuals (69.4%). Educational attainment varied, with 32 participants (17.5%) reporting illiteracy and 82(44.8%) holding a high school diploma, representing the largest subgroup. Occupational distribution revealed 78 housewives (42.6%), 88 retirees (48.1%), and 18 employed individuals (9.8%). Regarding family structure, 77 individuals (42.1%) had 4–6 children, while 10(5.5%) were childless. Self-rated health status was reported as good by 83 individuals (83)45.4%, neutral by 88(48.1%), and poor by 12(6.6%).

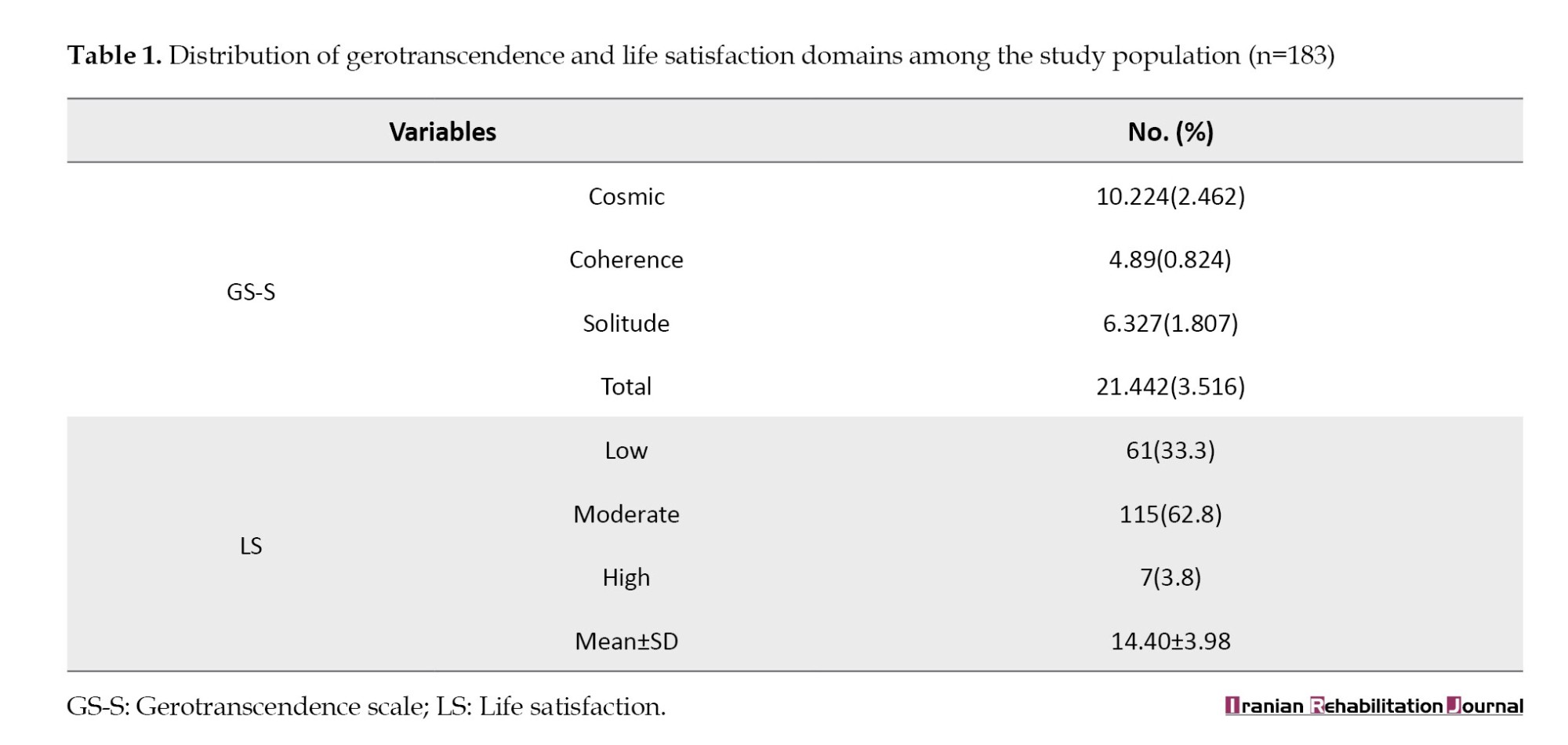

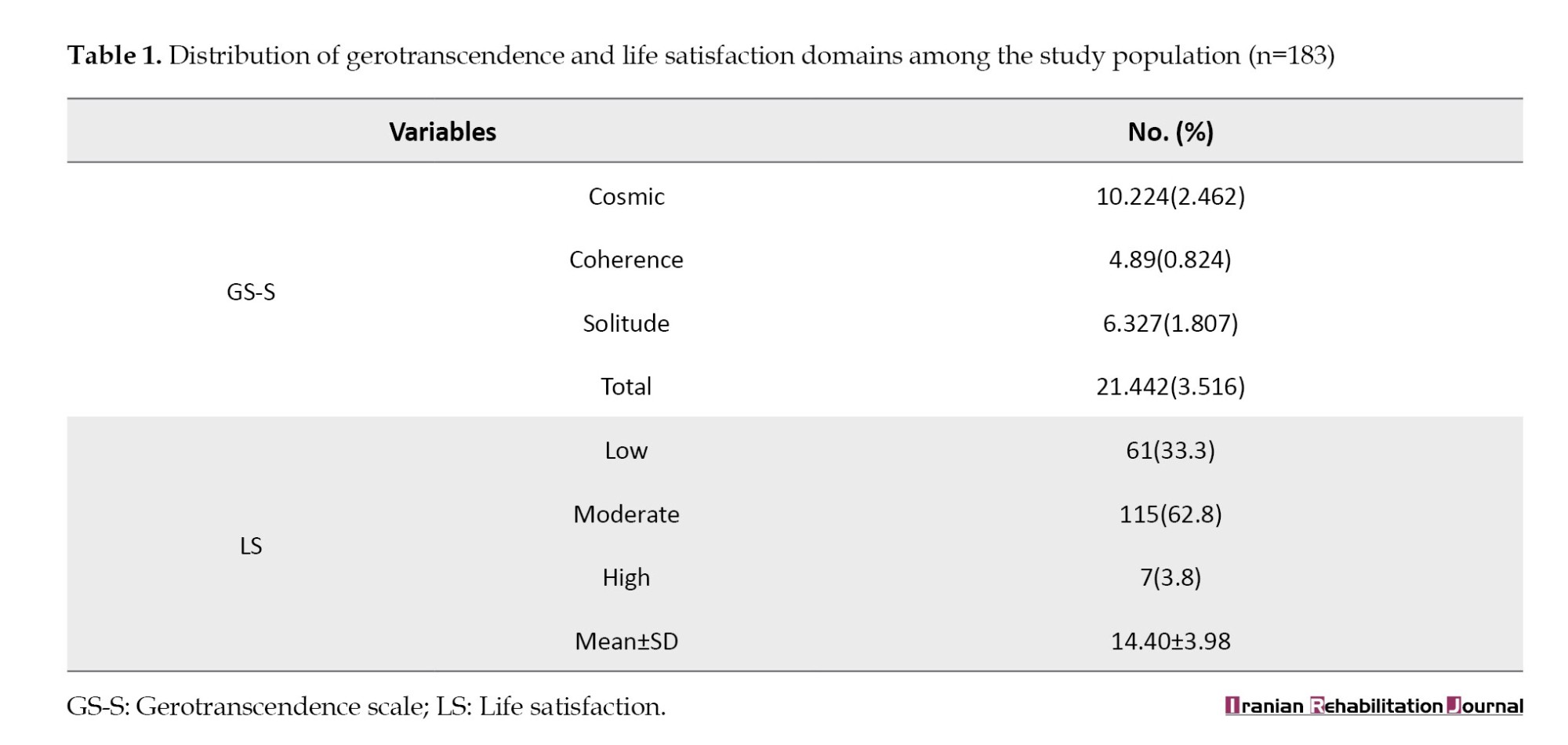

The mean gerotranscendence score was 21.44±3.51, with the cosmic dimension exhibiting the highest subscale mean. The average life satisfaction score was 14.40±3.98, with 115 participants (62.8%) reporting moderate satisfaction (Table 1).

Independent samples t-tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed no statistically significant differences in gerotranscendence scores by gender (P=0.194), number of children (P=0.405), marital status (P=0.865), education (P=0.527), occupation (P=0.819), or health status (P=0.608). Conversely, life satisfaction differed significantly by education (P=0.005) and health status (P=0.014), but not by gender (P=0.894), children (P=0.519), marital status (P=0.260), or job (P=0.115).

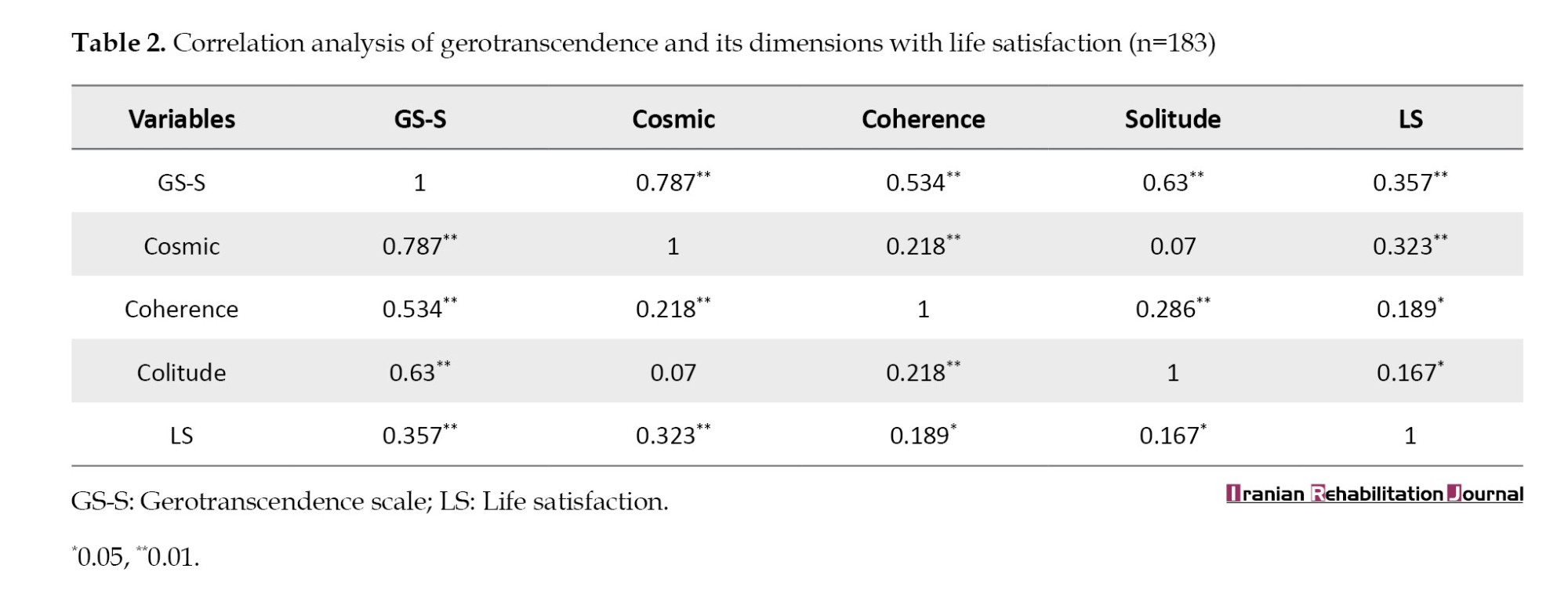

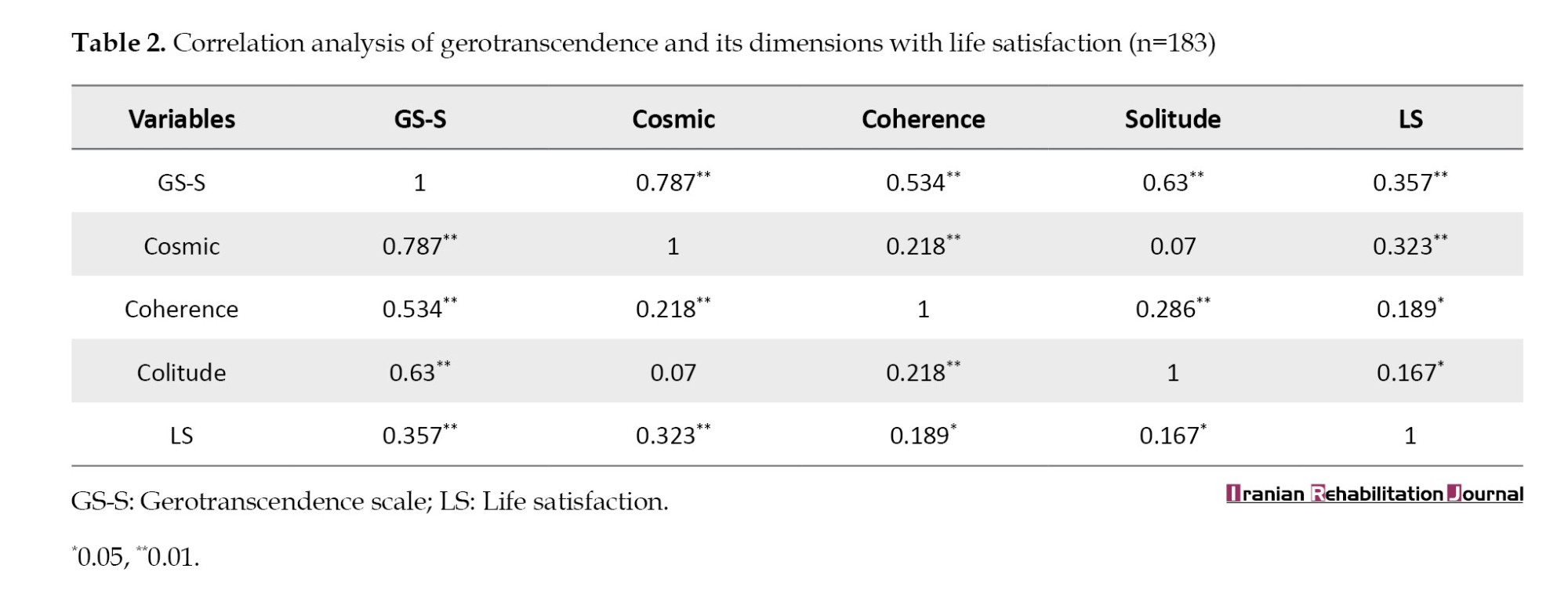

Pearson’s correlation demonstrated a positive, statistically significant association between gerotranscendence and life satisfaction (r=0.357, P<0.01) (Table 2).

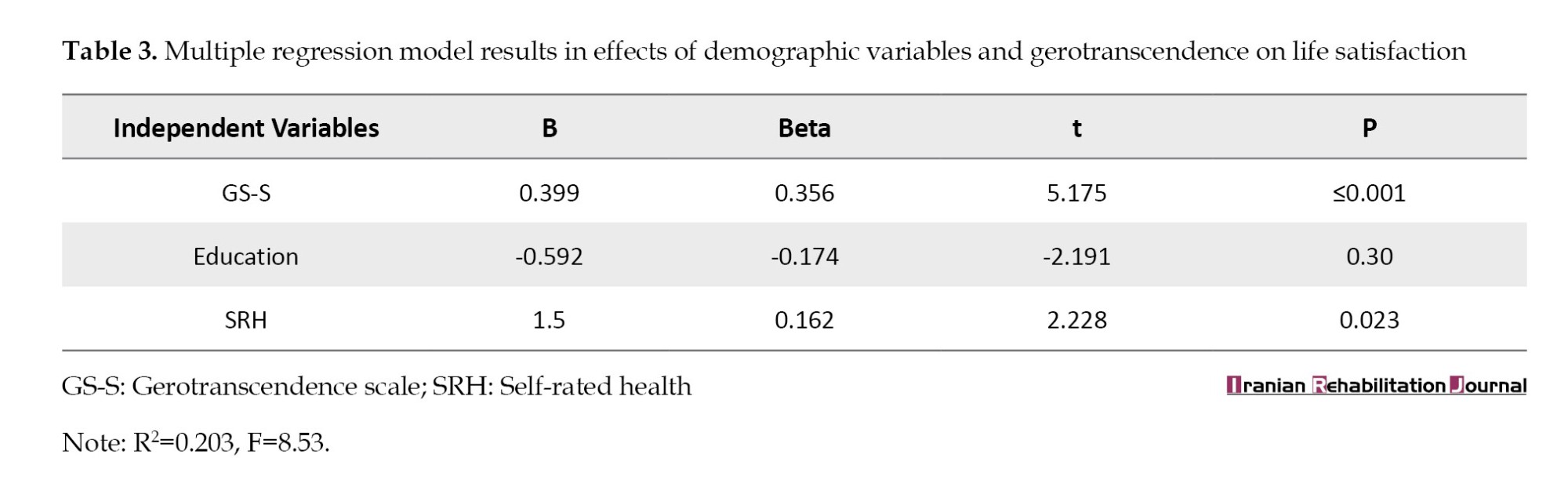

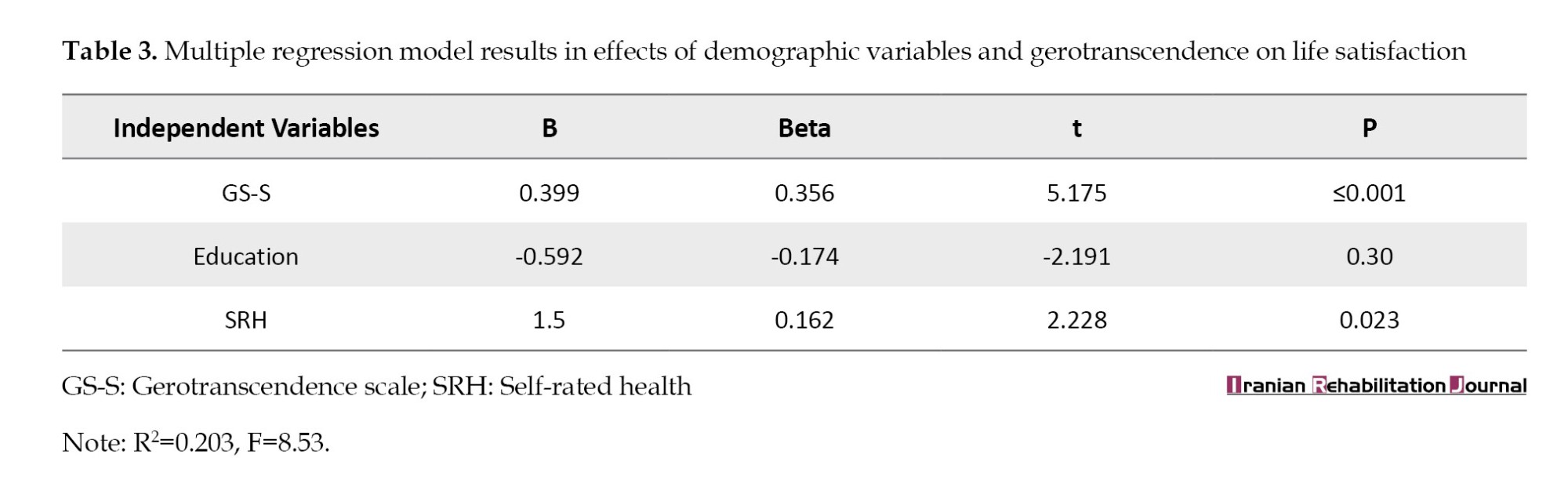

Multiple linear regression indicated that gerotranscendence explained 20.3% of the variance (R2=0.203) in life satisfaction. The final model identified self-rated health and education as significant predictors (P<0.05) (Table 3).

Discussion

We conducted a population-based survey of older adults residing in Kerman City. Our approach combined the strengths of face-to-face interviews, validated questionnaires, and a rigorous sampling design. To ensure broad representation, we randomly selected participants from 10 of the city’s 47 PHCs, thus capturing a diverse cross-section of the older population. This method not only enhanced the reliability of our findings but also supported the generalizability of our results to a wider urban older population in Kerman City.

Based on the results, the older population studied exhibited a moderate level of gerotranscendence, which is consistent with the findings of some studies [26, 27]. Among the dimensions of gerotranscendence, the cosmic dimension had a higher average score, which is consistent with the results of a study by Read et al. in Amsterdam [28]. This may be because older adults in the community cannot assume a successful old age. Some believe that life after entering old age is devoid of meaning. According to Tornstam, with a rigorous estimate, only 20% of the population automatically and effortlessly reach higher levels of gerotranscendence [7]. In contrast, the theory of gerotranscendence claims that spiritual development gradually increases from middle age onwards. However, it does not follow the activity patterns and values of old age, and the process is different in the older population because it can be promoted or suppressed by normative and situational structures, social class, and education level [29, 30]. In the process of genuine growth, the “self” can be transcended by the “cosmic self” through the breaking down of limiting walls. The ontological recognition of oneself as an integral constituent of the cosmos facilitates a profound existential realization in which the universal continuum of existence assumes paramount significance. This metacognitive shift engenders two interrelated phenomenological outcomes: 1) An attenuation of thanatophobic anxiety through the conceptualization of death as a natural phase within the cosmic order, and 2) An intensification of temporal transcendence-a heightened sense of connection that transcends chronological boundaries, creating a perceived unity with ancestral, contemporary, and subsequent generations [31].

The results also showed that the majority of the older population studied had a moderate level of life satisfaction, which is consistent with the findings of similar studies [11, 28] and inconsistent with those of other studies. However, some studies have reported an increase in life satisfaction with aging [15, 32, 33], while others have found a negative relationship between aging and life satisfaction [34, 35]. This discrepancy may be due to the fact that life satisfaction in older adults can vary under the influence of economic, social, and cultural factors, as well as physical and mental conditions. In contrast, people’s perception of the concept of life satisfaction is usually a relative concept. As a result, it can create different perspectives for different people.

The primary finding of this study was that gerotranscendence, along with its three dimensions, has a significant positive relationship with life satisfaction. Wang et al. reported that after the gerotranscendence-based intervention, the mean score of life satisfaction increased significantly [10]. In a similar study, using semi-structured interviews with religious and secular Iranians living in Sweden and religious and secular Turkish people living in Turkey, it was found that all those who presented evidence of gerotranscendence also showed evidence of life satisfaction. In a study, some secularists showed signs of life satisfaction similar to those of religious people, but did not show signs of gerotranscendence. On the contrary, none of the religious and secular Iranians showed evidence of life satisfaction in the absence of gerotranscendence [36]. In a study by Hoshino et al., gerotranscendence was found to have a positive relationship with the scale of integration, and life satisfaction was also positively correlated [37]. Also, several studies have confirmed the positive effect of gerotranscendence-based interventions on life satisfaction, and the discussion of gerotranscendence theory is associated with higher levels of life satisfaction [10, 11]. In contrast, Kalavar et al. showed that the relationship between gerotranscendence and life satisfaction was not statistically significant [38]. This difference may be due to the fact that this study was conducted during a religious ceremony, and most participants were men; therefore, its generalizability is reduced.

The findings of the present study showed that gerotranscendence theory, which leads to a shift in a person’s perspective from a materialist to a transcendent perspective [7], can increase the level of life satisfaction. On the most obvious level, the existence of a transcendent perspective toward life enables individuals to see their lives and everything that has afflicted them in a larger and more meaningful context. The existence of gerotranscendence and life satisfaction in individuals can be explained by adopting a transcendent perspective toward oneself and the world (gerotranscendence), which counteracts life’s deficiencies and disappointments.

Individuals can experience transcendence before reaching old age. However, not everyone reaches this stage in old age. However, aging is the most conducive stage for transcendence, which reflects ultimate human development [39]. Tornstam’s theory of gerotranscendence posits that the aging process facilitates a developmental shift in which individuals progressively transcend earlier psychological constraints. This transformation is characterized by: 1) A reduction in egocentric tendencies, 2) Increased emotional equanimity, and 3) Enhanced connection with the natural world. Central to this theoretical framework is the capacity of older adults to reconcile existential ambiguities and apparent paradoxes, leading to a more nuanced understanding of moral absolutism and a reduced tendency toward categorical judgments. Tornstam maintains that while wisdom represents a potential outcome of this developmental trajectory, its attainment is not universal among aging individuals. From a symbolic interactionist perspective, Tornstam conceptualizes later life as an ongoing process of self-actualization, wherein individuals continue to confront and transform personal limitations into strengths. The theory predicts several observable behavioral changes, including a decreased preoccupation with material possessions, selective withdrawal from superficial social engagements, and a reallocation of temporal resources toward intrinsically meaningful activities, such as contemplative practices (e.g. meditation), philosophical inquiry, and spiritual devotion. These behavioral manifestations reflect an underlying ontological reorientation toward transcendent values and existential meaning [7]. However, it is worth mentioning that the development of gerotranscendence is not only a product of aging but also of the culture and way of thinking of the people.

Several methodological limitations should be considered when interpreting these findings. First, the exclusive reliance on self-report measures introduces potential response biases, including social desirability effects and retrospective recall inaccuracies, which may systematically distort the reported associations between study variables. Second, while our sampling strategy ensured representativeness within the study context, the modest sample size constrains the statistical power and external validity of results, particularly regarding their generalizability to diverse PHC populations. Third, the cross-sectional design fundamentally precludes causal interpretation of the observed relationships between gerotranscendence dimensions and life satisfaction outcomes.

These limitations suggest several promising avenues for future research. Longitudinal cohort studies employing repeated measurements can elucidate the developmental trajectory of gerotranscendence and its temporal relationship with indicators of psychological well-being. Experimental designs, including randomized controlled trials of gerotranscendence-informed interventions (e.g. structured life review therapies, spiritually integrated reminiscence protocols, or nature-based contemplative practices), would help establish causal efficacy while controlling for potential confounding variables. Particular attention should be given to developing culturally adapted intervention modalities that operationalize cosmic transcendence and ego integrity through locally meaningful practices (e.g. Quranic reflection groups or intergenerational wisdom-sharing circles in Islamic contexts). Such research would advance both theoretical understanding and practical application of gerotranscendence principles in geriatric care and health promotion programming.

Conclusion

Adopting a gerotranscendence perspective is crucial for enhancing life satisfaction among older adults, as it fosters a more holistic and meaningful approach to aging that aligns with the evolving values and perspectives. To foster this shift, policymakers should prioritize two key actions:

1) Develop and implement health promotion and intervention programs: Programs that integrate gerotranscendence principles can empower older adults to find deeper purpose and connection, which is vital for their mental and emotional well-being. These initiatives may include activities that emphasize reflective thinking, intergenerational engagement, and self-acceptance, all of which support a positive transformation in older adults’ perspectives. 2) Enhance care planning based on gerotranscendence theory: By incorporating gerotranscendence into care planning, healthcare providers and caregivers can tailor services that align with older adults’ transcendent views, addressing their needs beyond the physical and focusing on psychological and existential well-being. This approach would not only boost life satisfaction but also cultivate a caring environment that respects the unique developmental stage of older adults.

In conclusion, incorporating gerotranscendence into aging policies and practices has the potential to profoundly enhance the quality of life of older adults, ultimately creating a more compassionate and meaningful experience of aging.

Implications for practice

1) Gerotranscendence as a framework for holistic aging: Gerotranscendence offers a vital theoretical lens for understanding the psychosocial and existential dimensions of aging, positing that older adults naturally evolve toward deeper spiritual, cosmic, and existential awareness. Recognizing this developmental trajectory can inform interventions that align with older adults’ evolving needs, thereby fostering resilience and purpose in later life. 2) Spiritual growth as a developmental continuum: The theory underscores that spiritual growth is a gradual process, often emerging in midlife and intensifying with age. Healthcare providers and community programs should adopt a lifespan approach to spiritual support, integrating opportunities for reflection, meaning-making, and existential exploration tailored to different stages of older adulthood. 3) Lifestyle factors and life satisfaction: Empirical evidence suggests that health behaviors, social connectedness, and engagement in purposeful activities are critical determinants of life satisfaction in aging populations. Interventions should prioritize activities that resonate with gerotranscendence principles, such as legacy projects, intergenerational mentoring, or nature-based mindfulness practices, to enhance fulfillment and psychological well-being. 4) Adaptive reframing and self-perception: Life satisfaction in older adults is closely tied to their ability to adaptively reinterpret life experiences, reconcile past achievements, and affirm their societal role. Strengths-based counseling, narrative therapy, and guided life-review exercises can help older adults reframe challenges, cultivate a sense of ego integrity, and affirm their enduring contributions. 5) Systemic integration of gerotranscendence principles: Policymakers, healthcare providers, and caregivers should collaborate to design environments and programs that nurture transcendent aging.

Key strategies include:

1) Structured reflective practices: Facilitated group discussions, reminiscence therapy, or wisdom-sharing circles to explore existential themes. 2) Culturally attuned spiritual engagement: Community programs incorporating faith-based reflections (e.g. Quranic study groups, meditation on impermanence) or intergenerational storytelling to foster cosmic connectedness. 3) Institutional support: Training PHC staff to identify and support transcendent needs, embedding gerotranscendence modules into senior center activities, and advocating for policies that fund psychosocial-spiritual aging research.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran (Code: IR.KMU.REC.1397.547) and conducted by the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before their inclusion in the study.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Today, alongside the growth of the older population worldwide, the social paradigm of aging is evolving [1]. As life expectancy rises, the proportion of older adults within the population grows accordingly, exposing them to significant shifts in their social networks, socioeconomic status, health conditions, and demographic circumstances [2]. In recent decades, numerous theoretical frameworks have been developed to conceptualize the process of healthy aging. Nonetheless, despite the assertions of certain models, a universally accepted definition supported by robust empirical evidence remains elusive [3]. In other words, many early studies on aging have been organized around the concept of adaptation and have focused on matching individuals with the loss of role to explain the concept of successful or normal aging [4, 5].

The theory of gerotranscendence, introduced by Lars Tornstam in 1989, is a pivotal framework for understanding the social and psychological dimensions of aging. This theory offers a transformative perspective on aging, portraying it as a lifelong developmental process [6]. Gerotranscendence encompasses three primary dimensions: The cosmic dimension, which reflects a deepened sense of connection with the universe and a redefined perception of the self as part of a larger whole; the coherence dimension, emphasizing life’s overall meaning and internal consistency; and the dimension of positive solitude, which highlights a reassessment of interpersonal relationships and the value of being alone [7, 8]. Tornstam described gerotranscendence as “a shift in meta-perspective from a materialistic and rational view of the world to a more cosmic and transcendent one,” a transformation often associated with enhanced life satisfaction [9]. The positive effect of many gerotranscendence-based interventions on life satisfaction levels has been confirmed in some studies, leading to a discussion on gerotranscendence and its potential to achieve higher life satisfaction levels [10, 11].

Life satisfaction in older adults is shaped by their ability to adapt to age-related changes and their subjective evaluation of their life circumstances, viewed through the lens of their cultural background, personal values, goals, expectations, and concerns [12, 13]. However, studies have reported contradictory findings on the level of life satisfaction among the elderly. Some studies have reported that older adults generally do not experience high levels of life satisfaction [14], while others have found moderate to high levels of life satisfaction in older adults [14, 15]. It appears that the elderly’s lifestyle has a significant impact on their satisfaction, and economic, social, and cultural factors also influence the level of life satisfaction [16]. However, life satisfaction is considered one of the most important indicators of mental health in old age, as it reflects a person’s attitude toward their life and can reflect their feelings about their past, present, or future [17, 18]. This indicator affects many aspects of the elderly’s life, such as self-care and health behaviors. Also, life dissatisfaction in older adults is associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality in men and cardiovascular mortality in women [19, 20].

The concept of gerotranscendence emphasizes how the experience and interpretation of aging can shift profoundly as individuals move from a materialistic, externally oriented view of life toward a more cosmic and introspective perspective [21]. This shift is heavily influenced by culture and social norms, meaning that gerotranscendence may manifest differently across societies with varying values, structures, and views on aging [22]. Gerontological research in Iran is still in its early stages, particularly in studies that integrate socio-psychological frameworks, such as gerotranscendence theory. A critical yet underexplored area is the potential influence of Islamic teachings, including the emphasis on spiritual maturation in late adulthood, veneration of elders, and eschatological beliefs on the developmental dimensions of gerotranscendence. Additionally, Iran’s collectivist sociocultural fabric, characterized by strong intergenerational cohesion and familial interdependence, may differentially facilitate or constrain specific facets of gerotranscendence, such as cosmic transcendence (i.e. a sense of unity with the universe) and ego integrity (i.e. reconciliation with one’s life narrative). There is a pressing need to expand such studies to better understand the aging experience within the Iranian sociocultural context. Research grounded in socio-psychological theories of aging can provide new insights into the psychological processes that shape well-being in later life, especially regarding key outcomes, such as life satisfaction. Among these theories, gerotranscendence stands out for its relevance to life satisfaction, a critical factor in the quality of life of older adults. Recognizing this gap, our study aims to investigate the relationship between gerotranscendence and life satisfaction among Iranian older adults, to contribute to a foundational understanding of how transcendent thinking can enrich the aging process and enhance life satisfaction in later years. This exploration not only advances academic knowledge but also has practical implications for developing culturally appropriate interventions that support the well-being of older adults.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional, population-based study employing an analytical-descriptive approach, targeting older adults aged >60 years. This study was conducted in Kerman City, Iran, over six months, from October 2022 to March 2023. Kerman is the capital city of Kerman Province, located 1 038 km from Tehran. It is the largest and most developed city in Kerman Province, and the most crucial city in southeastern Iran. According to the 2016 census, the population was 738 724. Kerman City, situated on the elevated periphery of the Lut Desert in south-central Iran, is encircled by mountain ranges and renowned for its rich historical and cultural legacy. The city is home to numerous ancient architectural landmarks, reflecting its deep-rooted heritage. Kerman’s economy is primarily sustained by agriculture and mining, with pistachio cultivation as a key economic driver. Administratively, the city is divided into four subdistricts and served by a single health center.

Populations and sample size

Participants were recruited from primary healthcare centers (PHCs) across Kerman, which are designated to implement the national program for integrated care of older adults. In total, 47 PHCs in the city are formally engaged in delivering this national initiative, providing services specifically tailored to the needs of the older adult population. The comprehensive elderly care program is an integrated and comprehensive elderly care program for physicians and non-physicians. Older adults are evaluated in terms of priority physical and mental illnesses based on the burden of illness and immunization, and this evaluation is supplemented by simple diagnostic and treatment methods. They will also receive health education to prevent disease.

The required sample size was calculated using a standard statistical formula for estimating population means, yielding a target of 200 participants. A two-stage cluster sampling approach was employed to ensure representativeness. First, 10 of the 47 PHCs were selected through probability proportional to size sampling, ensuring that larger PHCs had a higher chance of inclusion. Subsequently, within each selected PHC (cluster), 20 subjects were randomly chosen using a simple random sampling technique. This was achieved by assigning a unique random number to each patient record and systematically selecting participants based on a predetermined sampling interval. Most older adults covered by PHCs have a record; therefore, all participants were randomly selected from the available records. The inclusion criteria were: Age ≥60 years, Iranian citizenship, and willingness to provide informed consent to use data and participate. Each subject was then contacted at home through house visits, and additional data were collected, with participation requested. The questionnaires were self-administered by literate participants and interviewer-administered (gender-matched) for those who were illiterate.

Instrument

The instruments used to collect data included a form addressing socio-demographic variables, two validated questionnaires, and a question concerning self-reported health status with options of ‘good,’ ‘neither good nor bad,’ and ‘bad’.

Gerotranscendence was determined by using Tornstam’s short-form gerotranscendence scale (GS-S), which had 10 items in the form of a 4-point Likert-type scale (strongly agree=4 to strongly disagree=1; and reverse scoring for items 6 and 9). GS-S has three dimensions (sub-scales): The cosmic dimension (five items), the coherence dimension (two items), and the solitude dimension (three items). This questionnaire has been validated in the Iranian population. Cronbach’s α and coefficient omega of the scale were 0.72 and 0.82, respectively. Test, re-test reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC]=0.88, P<001), and the standard error of measurement was 1.16 (confidence interval [CI]=95%) [23].

Life satisfaction was determined using the life satisfaction index-Z (LSIZ). The original LSIZ contained 20 items. The LSIZ was proposed by Wood et al. using 13 of the 20 items from the LSIA [24]. The participants expressed their agreement or disagreement with the statements using a 3-point Likert scale (agree=2, disagree=1, and I do not know=0). The total score ranged from 0 to 26. A score between 0-12 indicated low Life Satisfaction, a score between 13-21 indicated moderate life satisfaction, and a score of 22 and above indicated high life satisfaction. This questionnaire has already been validated in the Iranian population, and Cronbach’s α of this scale was 0.79 [25].

Data analysis

Ultimately, 17 questionnaires were excluded due to incomplete or invalid responses, leaving 183 questionnaires for final analysis. Data were processed using SPSS software, version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). As the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test confirmed a normal distribution of the data, both descriptive and inferential statistical methods were employed for analysis.

Results

The study included 183 older adults, with a mean age of 66.7±7.14 years. The sample comprised 99 females (54.1%) and 127 married individuals (69.4%). Educational attainment varied, with 32 participants (17.5%) reporting illiteracy and 82(44.8%) holding a high school diploma, representing the largest subgroup. Occupational distribution revealed 78 housewives (42.6%), 88 retirees (48.1%), and 18 employed individuals (9.8%). Regarding family structure, 77 individuals (42.1%) had 4–6 children, while 10(5.5%) were childless. Self-rated health status was reported as good by 83 individuals (83)45.4%, neutral by 88(48.1%), and poor by 12(6.6%).

The mean gerotranscendence score was 21.44±3.51, with the cosmic dimension exhibiting the highest subscale mean. The average life satisfaction score was 14.40±3.98, with 115 participants (62.8%) reporting moderate satisfaction (Table 1).

Independent samples t-tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed no statistically significant differences in gerotranscendence scores by gender (P=0.194), number of children (P=0.405), marital status (P=0.865), education (P=0.527), occupation (P=0.819), or health status (P=0.608). Conversely, life satisfaction differed significantly by education (P=0.005) and health status (P=0.014), but not by gender (P=0.894), children (P=0.519), marital status (P=0.260), or job (P=0.115).

Pearson’s correlation demonstrated a positive, statistically significant association between gerotranscendence and life satisfaction (r=0.357, P<0.01) (Table 2).

Multiple linear regression indicated that gerotranscendence explained 20.3% of the variance (R2=0.203) in life satisfaction. The final model identified self-rated health and education as significant predictors (P<0.05) (Table 3).

Discussion

We conducted a population-based survey of older adults residing in Kerman City. Our approach combined the strengths of face-to-face interviews, validated questionnaires, and a rigorous sampling design. To ensure broad representation, we randomly selected participants from 10 of the city’s 47 PHCs, thus capturing a diverse cross-section of the older population. This method not only enhanced the reliability of our findings but also supported the generalizability of our results to a wider urban older population in Kerman City.

Based on the results, the older population studied exhibited a moderate level of gerotranscendence, which is consistent with the findings of some studies [26, 27]. Among the dimensions of gerotranscendence, the cosmic dimension had a higher average score, which is consistent with the results of a study by Read et al. in Amsterdam [28]. This may be because older adults in the community cannot assume a successful old age. Some believe that life after entering old age is devoid of meaning. According to Tornstam, with a rigorous estimate, only 20% of the population automatically and effortlessly reach higher levels of gerotranscendence [7]. In contrast, the theory of gerotranscendence claims that spiritual development gradually increases from middle age onwards. However, it does not follow the activity patterns and values of old age, and the process is different in the older population because it can be promoted or suppressed by normative and situational structures, social class, and education level [29, 30]. In the process of genuine growth, the “self” can be transcended by the “cosmic self” through the breaking down of limiting walls. The ontological recognition of oneself as an integral constituent of the cosmos facilitates a profound existential realization in which the universal continuum of existence assumes paramount significance. This metacognitive shift engenders two interrelated phenomenological outcomes: 1) An attenuation of thanatophobic anxiety through the conceptualization of death as a natural phase within the cosmic order, and 2) An intensification of temporal transcendence-a heightened sense of connection that transcends chronological boundaries, creating a perceived unity with ancestral, contemporary, and subsequent generations [31].

The results also showed that the majority of the older population studied had a moderate level of life satisfaction, which is consistent with the findings of similar studies [11, 28] and inconsistent with those of other studies. However, some studies have reported an increase in life satisfaction with aging [15, 32, 33], while others have found a negative relationship between aging and life satisfaction [34, 35]. This discrepancy may be due to the fact that life satisfaction in older adults can vary under the influence of economic, social, and cultural factors, as well as physical and mental conditions. In contrast, people’s perception of the concept of life satisfaction is usually a relative concept. As a result, it can create different perspectives for different people.

The primary finding of this study was that gerotranscendence, along with its three dimensions, has a significant positive relationship with life satisfaction. Wang et al. reported that after the gerotranscendence-based intervention, the mean score of life satisfaction increased significantly [10]. In a similar study, using semi-structured interviews with religious and secular Iranians living in Sweden and religious and secular Turkish people living in Turkey, it was found that all those who presented evidence of gerotranscendence also showed evidence of life satisfaction. In a study, some secularists showed signs of life satisfaction similar to those of religious people, but did not show signs of gerotranscendence. On the contrary, none of the religious and secular Iranians showed evidence of life satisfaction in the absence of gerotranscendence [36]. In a study by Hoshino et al., gerotranscendence was found to have a positive relationship with the scale of integration, and life satisfaction was also positively correlated [37]. Also, several studies have confirmed the positive effect of gerotranscendence-based interventions on life satisfaction, and the discussion of gerotranscendence theory is associated with higher levels of life satisfaction [10, 11]. In contrast, Kalavar et al. showed that the relationship between gerotranscendence and life satisfaction was not statistically significant [38]. This difference may be due to the fact that this study was conducted during a religious ceremony, and most participants were men; therefore, its generalizability is reduced.

The findings of the present study showed that gerotranscendence theory, which leads to a shift in a person’s perspective from a materialist to a transcendent perspective [7], can increase the level of life satisfaction. On the most obvious level, the existence of a transcendent perspective toward life enables individuals to see their lives and everything that has afflicted them in a larger and more meaningful context. The existence of gerotranscendence and life satisfaction in individuals can be explained by adopting a transcendent perspective toward oneself and the world (gerotranscendence), which counteracts life’s deficiencies and disappointments.

Individuals can experience transcendence before reaching old age. However, not everyone reaches this stage in old age. However, aging is the most conducive stage for transcendence, which reflects ultimate human development [39]. Tornstam’s theory of gerotranscendence posits that the aging process facilitates a developmental shift in which individuals progressively transcend earlier psychological constraints. This transformation is characterized by: 1) A reduction in egocentric tendencies, 2) Increased emotional equanimity, and 3) Enhanced connection with the natural world. Central to this theoretical framework is the capacity of older adults to reconcile existential ambiguities and apparent paradoxes, leading to a more nuanced understanding of moral absolutism and a reduced tendency toward categorical judgments. Tornstam maintains that while wisdom represents a potential outcome of this developmental trajectory, its attainment is not universal among aging individuals. From a symbolic interactionist perspective, Tornstam conceptualizes later life as an ongoing process of self-actualization, wherein individuals continue to confront and transform personal limitations into strengths. The theory predicts several observable behavioral changes, including a decreased preoccupation with material possessions, selective withdrawal from superficial social engagements, and a reallocation of temporal resources toward intrinsically meaningful activities, such as contemplative practices (e.g. meditation), philosophical inquiry, and spiritual devotion. These behavioral manifestations reflect an underlying ontological reorientation toward transcendent values and existential meaning [7]. However, it is worth mentioning that the development of gerotranscendence is not only a product of aging but also of the culture and way of thinking of the people.

Several methodological limitations should be considered when interpreting these findings. First, the exclusive reliance on self-report measures introduces potential response biases, including social desirability effects and retrospective recall inaccuracies, which may systematically distort the reported associations between study variables. Second, while our sampling strategy ensured representativeness within the study context, the modest sample size constrains the statistical power and external validity of results, particularly regarding their generalizability to diverse PHC populations. Third, the cross-sectional design fundamentally precludes causal interpretation of the observed relationships between gerotranscendence dimensions and life satisfaction outcomes.

These limitations suggest several promising avenues for future research. Longitudinal cohort studies employing repeated measurements can elucidate the developmental trajectory of gerotranscendence and its temporal relationship with indicators of psychological well-being. Experimental designs, including randomized controlled trials of gerotranscendence-informed interventions (e.g. structured life review therapies, spiritually integrated reminiscence protocols, or nature-based contemplative practices), would help establish causal efficacy while controlling for potential confounding variables. Particular attention should be given to developing culturally adapted intervention modalities that operationalize cosmic transcendence and ego integrity through locally meaningful practices (e.g. Quranic reflection groups or intergenerational wisdom-sharing circles in Islamic contexts). Such research would advance both theoretical understanding and practical application of gerotranscendence principles in geriatric care and health promotion programming.

Conclusion

Adopting a gerotranscendence perspective is crucial for enhancing life satisfaction among older adults, as it fosters a more holistic and meaningful approach to aging that aligns with the evolving values and perspectives. To foster this shift, policymakers should prioritize two key actions:

1) Develop and implement health promotion and intervention programs: Programs that integrate gerotranscendence principles can empower older adults to find deeper purpose and connection, which is vital for their mental and emotional well-being. These initiatives may include activities that emphasize reflective thinking, intergenerational engagement, and self-acceptance, all of which support a positive transformation in older adults’ perspectives. 2) Enhance care planning based on gerotranscendence theory: By incorporating gerotranscendence into care planning, healthcare providers and caregivers can tailor services that align with older adults’ transcendent views, addressing their needs beyond the physical and focusing on psychological and existential well-being. This approach would not only boost life satisfaction but also cultivate a caring environment that respects the unique developmental stage of older adults.

In conclusion, incorporating gerotranscendence into aging policies and practices has the potential to profoundly enhance the quality of life of older adults, ultimately creating a more compassionate and meaningful experience of aging.

Implications for practice

1) Gerotranscendence as a framework for holistic aging: Gerotranscendence offers a vital theoretical lens for understanding the psychosocial and existential dimensions of aging, positing that older adults naturally evolve toward deeper spiritual, cosmic, and existential awareness. Recognizing this developmental trajectory can inform interventions that align with older adults’ evolving needs, thereby fostering resilience and purpose in later life. 2) Spiritual growth as a developmental continuum: The theory underscores that spiritual growth is a gradual process, often emerging in midlife and intensifying with age. Healthcare providers and community programs should adopt a lifespan approach to spiritual support, integrating opportunities for reflection, meaning-making, and existential exploration tailored to different stages of older adulthood. 3) Lifestyle factors and life satisfaction: Empirical evidence suggests that health behaviors, social connectedness, and engagement in purposeful activities are critical determinants of life satisfaction in aging populations. Interventions should prioritize activities that resonate with gerotranscendence principles, such as legacy projects, intergenerational mentoring, or nature-based mindfulness practices, to enhance fulfillment and psychological well-being. 4) Adaptive reframing and self-perception: Life satisfaction in older adults is closely tied to their ability to adaptively reinterpret life experiences, reconcile past achievements, and affirm their societal role. Strengths-based counseling, narrative therapy, and guided life-review exercises can help older adults reframe challenges, cultivate a sense of ego integrity, and affirm their enduring contributions. 5) Systemic integration of gerotranscendence principles: Policymakers, healthcare providers, and caregivers should collaborate to design environments and programs that nurture transcendent aging.

Key strategies include:

1) Structured reflective practices: Facilitated group discussions, reminiscence therapy, or wisdom-sharing circles to explore existential themes. 2) Culturally attuned spiritual engagement: Community programs incorporating faith-based reflections (e.g. Quranic study groups, meditation on impermanence) or intergenerational storytelling to foster cosmic connectedness. 3) Institutional support: Training PHC staff to identify and support transcendent needs, embedding gerotranscendence modules into senior center activities, and advocating for policies that fund psychosocial-spiritual aging research.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran (Code: IR.KMU.REC.1397.547) and conducted by the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before their inclusion in the study.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Abreu T, Araújo L, Teixeira L, Ribeiro O. "What Does Gerotranscendence Mean to You?" Older Adults' Lay Perspectives on the Theory. The Gerontologist. 2025; 65(5):gnaf077.[DOI:10.1093/geront/gnaf077] [PMID]

- World Health Organization. World report on ageing and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. [Link]

- Shooshtari S, Menec V, Swift A, Tate R. Exploring ethno-cultural variations in how older Canadians define healthy aging: The Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA). Journal of Aging Studies. 2020; 52:100834. [DOI:10.1016/j.jaging.2020.100834] [PMID]

- Degges‐White S. Understanding gerotranscendence in older adults: A new perspective for counselors. Adultspan Journal. 2005; 4(1):36-48. [DOI:10.1002/j.2161-0029.2005.tb00116.x]

- Michel JP, Graf C, Ecarnot F. Individual healthy aging indices, measurements and scores. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research. 2019; 31:1719–25. [DOI:10.1007/s40520-019-01327-y]

- Jönson H, Magnusson JA. A new age of old age?: Gerotranscendence and the re-enchantment of aging. Journal of Aging Studies. 2001; 15(4):317-31. [DOI:10.1016/S0890-4065(01)00026-3]

- Tornstam L. Maturing into gerotranscendence. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology. 2011; 43(2):166–80. [Link]

- Tornstam L. Gerotranscendence from young old age to old old age. The Social Gerontology Group, Uppsala. 2003. [Link]

- Tornstam L. Life crises and gerotranscendence. Journal of Aging and Identity. 1997; 2:117-31. [Link]

- Wang JJ, Lin YH, Hsieh LY. Effects of gerotranscendence support group on gerotranscendence perspective, depression, and life satisfaction of institutionalized elders. Aging & Mental Health. 2011; 15(5):580-6. [DOI:10.1080/13607863.2010.543663] [PMID]

- Meléndez-Moral JC, Charco-Ruiz L, Mayordomo-Rodríguez T, Sales-Galán A. Effects of a reminiscence program among institutionalized elderly adults. Psicothema. 2013; 25(3):319-23. [DOI:10.7334/psicothema2012.253] [PMID]

- Celik SS, Celik Y, Hikmet N, Khan MM. Factors affecting life satisfaction of older adults in Turkey. International Journal of Aging & Human Development. 2018; 87(4):392-414. [DOI:10.1177/0091415017740677] [PMID]

- Khodabakhsh S. Factors affecting life satisfaction of older adults in Asia: A systematic review. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2022; 23(3):1289-304. [DOI:10.1007/s10902-021-00433-x]

- Borhaninejad V, Nabvi S, Lotfalinezhad E, Amini F, Mansouri T. [Relationship between Social participation and life satisfaction among older people (Persian)]. Journal of North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences. 2017; 8(4):701-11. [DOI:10.18869/acadpub.jnkums.8.4.701]

- Aslani Y, Hosseini R, Alijanpour-Aghamaleki M, Ghahfarokhi R, Borhaninejad V. [Spiritual health and life satisfaction in older adults in Shahrekord hospitals, 2013 (Persian)]. Journal of Clinical Nursing and Midwifery. 2017; 6(4):1-10. [Link]

- Lim HJ, Min DK, Thorpe L, Lee CH. Multidimensional construct of life satisfaction in older adults in Korea: A six-year follow-up study. BMC Geriatrics. 2016; 16(1):197. [DOI:10.1186/s12877-016-0369-0]

- Ôzer M. A study on the life satisfaction of elderly individuals living in family environment and nursing homes. Turkish Journal of Geriatrics. 2004; 7(1):33-6. [Link]

- Bagherzadeh Cham M, Mohseni-Bandpei MA, Bahramizadeh M, Kalbasi S, Biglarian A. The effects of Vibro-medical insole on vibrotactile sensation in diabetic patients with mild-to-moderate peripheral neuropathy. Neurological Sciences. 2018; 39(6):1079-84. [DOI:10.1007/s10072-018-3318-1] [PMID]

- Kimm H, Sull JW, Gombojav B, Yi SW, Ohrr H. Life satisfaction and mortality in elderly people: The Kangwha Cohort Study. BMC Public Health. 2012; 12:54. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-12-54] [PMID]

- Golriz B, Ahmadi Bani M, Arazpour M, Bahramizadeh M, Curran S, Madani SP, et al. Comparison of the efficacy of a neutral wrist splint and a wrist splint incorporating a lumbrical unit for the treatment of patients with carpal tunnel syndrome. Prosthetics and Orthotics International. 2016; 40(5):617-23. [DOI:10.1177/0309364615592695] [PMID]

- Ahmadi F, Oghani Esfahani F. Dimensions of gerotranscendence among Iranian older adults: A phenomenological study. Educational Gerontology. 2024; 51(8):861-74. [DOI:10.1080/03601277.2024.2417451]

- Abreu T, Araújo L, Ribeiro O. How to promote gerotranscendence in older adults? A scoping review of interventions. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2023; 42(9):2036-47. [DOI:10.1177/07334648231169082] [PMID]

- Asiri S, Foroughan M, FadayeVatan R, Rassouli M, Montazeri A. Psychometric properties of the Persian version of the Gerotranscendence scale in community-dwelling older adults. Educational Gerontology. 2019; 45(10):636-44. [DOI:10.1080/03601277.2019.1678289]

- Wood V, Wylie ML, Sheafor B. An analysis of a short self-report measure of life satisfaction: Correlation with rater judgments. Journal of Gerontology. 1969; 24(4):465-9. [DOI:10.1093/geronj/24.4.465] [PMID]

- Taghdisi MH, Doshmangir P, Dehdari T, Doshmangir L. [Influencing factors on healthy lifestyle from viewpoint of ederly people: Qualitative study (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2013; 7(4):47-58. [Link]

- Wang K, Duan Gx, Jia HL, Xu ES, Chen XM, Xie HH. The level and influencing factors of gerotranscendence in community-dwelling older adults. International Journal of Nursing Sciences. 2015; 2(2):123-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnss.2015.04.001]

- Hsieh LY, Wang JJ. [The relationship between gerotranscendence and demographics in institutionalized elders (Chinese)]. Hu Li Za Zhi The Journal of Nursing. 2008; 55(6):37-46.[PMID]

- Read S, Braam AW, Lyyra TM, Deeg DJ. Do negative life events promote gerotranscendence in the second half of life? Aging & Mental Health. 2014; 18(1):117-24. [DOI:10.1080/13607863.2013.814101] [PMID]

- Atchley RC. How spiritual experience and development interact with aging. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology. 2011; 43(2):156-65. [Link]

- Jewell AJ. Tornstam’s notion of gerotranscendence: Re-examining and questioning the theory. Journal of Aging Studies. 2014; 30:112-20. [DOI:10.1016/j.jaging.2014.04.003]

- Jeong SYS, Moon KJ, Lee WS, David M. Experience of gerotranscendence among community‐dwelling older people: A cross‐sectional study. International Journal of Older People Nursing. 2019; 15(2):e12296. [DOI:10.1111/opn.12296]

- Gaymu J, Springer S. Living conditions and life satisfaction of older Europeans living alone: A gender and cross-country analysis. Ageing & Society. 2010; 30(7):1153-75. [DOI:10.1017/S0144686X10000231]

- Stone AA, Schwartz JE, Broderick JE, Deaton A. A snapshot of the age distribution of psychological well-being in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010; 107(22):9985-90. [DOI:10.1073/pnas.1003744107]

- Koohboomi M, Norasteh AA, Samami N. Effect of yoga training on balance in elderly women. Journal of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. 2015; 19(1):e70712. [DOI:10.22110/jkums.v19i1.2278]

- Baird BM, Lucas RE, Donnellan MB. Life satisfaction across the lifespan: Findings from two nationally representative panel studies. Social Indicators Research. 2010; 99(2):183-203. [DOI:10.1007/s11205-010-9584-9] [PMID]

- Lewin FA, Thomas LE. Gerotranscendence and life satisfaction: Studies of religious and secular Iranians and Turks. Journal of Religious Gerontology. 2001; 12(1):17-41. [DOI:10.1300/J078v12n01_04]

- Hoshino K, Zarit SH, Nakayama M. Development of the gerotranscendence scale type 2: Japanese version. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2012; 75(3):217-37. [DOI:10.2190/AG.75.3.b]

- Kalavar JM, Buzinde CN, Manuel-Navarrete D, Kohli N. Gerotranscendence and life satisfaction: Examining age differences at the Maha Kumbha Mela. Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging. 2015;27(1):2-15. [DOI:10.1080/15528030.2014.924086]

- Greenberger C. Gerotrancscendence through Jewish eyes. Journal of Religion and Health. 2012; 51(2):281-92. [DOI:10.1007/s10943-012-9590-0]

Article type: Original Research Articles |

Subject:

Aging Studies

Received: 2025/05/27 | Accepted: 2025/06/25 | Published: 2025/09/1

Received: 2025/05/27 | Accepted: 2025/06/25 | Published: 2025/09/1

Send email to the article author