Volume 15, Issue 3 (September 2017)

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2017, 15(3): 269-276 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Aghaie Meybodi F, Mohammadkhani P, Pourshahbaz A, Dolatshahi B, Havighurst S. Reducing Children Behavior Problems: A Pilot Study of Tuning in to Kids in Iran. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2017; 15 (3) :269-276

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-733-en.html

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-733-en.html

Fateme Aghaie Meybodi *1

, Parvaneh Mohammadkhani1

, Parvaneh Mohammadkhani1

, Abbas Pourshahbaz1

, Abbas Pourshahbaz1

, Behrooz Dolatshahi1

, Behrooz Dolatshahi1

, Sophie Havighurst2

, Sophie Havighurst2

, Parvaneh Mohammadkhani1

, Parvaneh Mohammadkhani1

, Abbas Pourshahbaz1

, Abbas Pourshahbaz1

, Behrooz Dolatshahi1

, Behrooz Dolatshahi1

, Sophie Havighurst2

, Sophie Havighurst2

1- Department of Clinical Psychology, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Centre for Training and Research in Developmental Health, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia.

2- Centre for Training and Research in Developmental Health, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia.

Keywords: Socialization, Emotion focused therapy, Parenting, Child, Mother child relations, Child behavior disorders.

Full-Text [PDF 525 kb]

(5794 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (14239 Views)

Full-Text: (2063 Views)

1. Introduction

Disruptive behavior problems in childhood are characterized by aggressive, oppositional defiant, and hyperactive behaviors [1] and can increase the risk for violence and substance abuse in adolescence and adulthood [2]. These behavior problems are affected by many factors including deficits in children’s emotional competence, especially problems in emotion regulation [3]. Emotion socialization is one of the principal factors contributing to children’s emotional competence [4].

Emotion socialization practices are determined by the beliefs of parents about their own expression and children’s negative emotions [5]. Socialization is influenced by the way parents regulate and express their emotions, whether they coach their children in understanding and regulating emotion, and their reactions to children’s negative emotion expression [4]. Emotion coaching and emotion dismissing are two emotion socialization parenting styles described by Gottman [5]. Emotion coaching parenting behaviors, such as validating children’s emotions, develop the competencies children need for managing their negative emotions [6]. In contrast, emotion dismissing parenting behaviors, such as minimizing children’s emotions, can be an obstacle for children learning to regulate their negative emotions [5].

The Tuning in to Kids (TIK) parenting program is an intervention that targets emotion socialization [7]. TIK is a group intervention for parents of preschoolers and has been developed in Australia. TIK concentrates on parental emotion socialization and helps parents learn emotion coaching to enhance children’s behavior and emotion regulation. In addition, the program targets the parents’ own emotion regulation so as to make parenting more responsive and less reactive. As a result, it is expected that parent–child relationships will improve, and child disruptive behaviors will be prevented or reduced [5, 8].

Different research studies have proven the efficacy of the TIK program in community and clinical samples of preschool children [9, 10]. For example, Havighurst and colleagues [11] evaluated TIK as an early intervention for preschool children with behavior problems and found that parents in the intervention condition reported less emotion dismissiveness and child behavior problems as well as greater emotion coaching and empathy.

Objectives

Behavioral parenting programs are the most commonly used approach to address child disruptive behavior problems in Iran. Emotion-focused interventions such as TIK are relatively new in the parenting literature, and the current study aimed to assess the efficacy of this promising approach on parenting practices and child behavior. This study is the first investigation of TIK used in Iran. It was hypothesized that the TIK program would increase parent emotion socialization and reduce child behavior problems.

2. Methods

Participants and sampling

Participants were 3-6 years old children with behavior problems who attended preschools in Tehran during 2016. The sample consisted of 54 mothers (Mean age=34.21 years, SD=4.79) with at least one child between 3.0 and 5.11 years of age (Mean age=4.33, SD=0.93) recruited from 18 preschools in diverse lower- to upper-class socio-economic areas of Tehran. All children (n=359) whose mothers expressed interest in attending a parenting program and participating in the research were screened using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) [12].

Inclusion criteria were having a 3-6 years old child with behavior problem. Exclusion criteria included a diagnosis of intellectual disability or pervasive developmental disorder. Children (N=74: 21%) with a T score of 65 or higher on the externalizing subscale of the CBCL were categorized as at risk and selected for this study. Of the 74 at-risk children, 54 children met the inclusion criteria and their mothers were interested in participating in the parenting program. As six mothers did not complete the program, final analyses were conducted with 48 participants. All mothers were married. Maternal education ranged from non-completion of high school (2.1%) to diploma (25%) and university education (73%). With regard to employment, 87.5% of mothers were not in paid work, and 12.5% were employed. Family income ranged from less than one million Tomans to over 5 million Tomans. All children lived with both parents, and 48% of children had two or more siblings.

Procedure

The research was a pre-test and post-test, quasi-experimental study that included a control group and baseline, immediate post-intervention, and 3-month follow-up assessments. Prior to starting the study, approval was obtained from the research ethics committee of the University of Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, and all mothers gave informed consent. Once recruited, the mothers were randomized into TIK intervention (n=27) or waitlist control condition (n=27) using a random number table. Mothers in the intervention group started the TIK program shortly after baseline assessment. The TIK program was offered to mothers in the waitlist control after the follow-up assessment was conducted. Mothers completed questionnaires about their child’s behavior problems as well as their emotion socialization and mental health. Two mothers from the intervention group and four mothers from control group dropped out at post-intervention and follow-up.

The TIK program is a structured, manualized group parenting program that was led by two facilitators (PhD student), trained by the TIK first author (Havighurst) who also supervised the intervention delivery. Fidelity checklists were completed after each session to ensure the program was delivered according to the manual. The facilitators delivered the TIK program for 120 minutes per week for six weeks. Two booster sessions were offered at two-monthly intervals after the initial six weeks. Three months after the last booster session, follow-up data were collected. The five steps of emotion coaching parenting [5] were taught via a set of psycho-education materials, role plays, DVD demonstrations, and home activities.

The focus of sessions was for parents to become aware of emotions, reflect and label emotions, and empathize with their child. TIK addresses fears and worries, anger, and problem solving for the children, and teaches emotion regulation strategies for parents including relaxation, self-care, and managing anger. Psycho-education including information about children’s emotional competence and the way different parenting styles contribute to the development of emotion regulation skills were provided. Parental meta-emotion, including parent’s family of origin experiences with emotions, was explored. Mothers were also encouraged to allocate a specific time for discussion about negative emotions with their child.

Measures

Child Behavior Checklist

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) [12] for preschool children was used to screen preschoolers for behavior problems. The CBCL has three domains: internalizing, externalizing, and total problems. CBCL is an appropriate measure for screening child behavior problems. “Subclinical” (T-score ≥60) and “clinical” (T-score ≥63) cut-off points have been defined [12]. In the current study, a T-score ≥65 on externalizing was used to select a sample at-risk. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha for externalizing scores was 0.89.

Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory

The Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (ECBI) [13] is a 36-item parent-report scale of behavior problems and was used in this study as an outcome measure. This psychometrically strong inventory has two components: an Intensity score, which measures the frequency of behaviors, and the Problem score, which determines whether the behavior is a problem or not. Many studies have used the ECBI and shown it to have excellent internal consistency, construct validity, and convergent validity [14]. The problem score with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92 was used in the current study as a parent-rated measure of child behavior problems.

Parent Emotional Style Questionnaire

The Parent Emotional Style Questionnaire (PESQ) [15] is a 21- item two-factor (Emotion Coaching and Emotion Dismissing) scale that was adapted from the 14-item Maternal Emotional Styles Questionnaire [16] to measure parent-reported emotion socialization. Parents rated their beliefs about child’s worry, anger and sadness. Cronbach’s alpha for Emotion Coaching ranged from 0.78 to 0.84 and for Emotion Dismissing ranged from 0.82 to 0.86 [11]. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for Emotion Dismissing was 0.83 and for Emotion Coaching was 0.76.

General Health Questionnaire

The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) [17] is a 28 item questionnaire with subscales of Severe Depression, Anxiety and Insomnia, Social Dysfunction, and Somatic Symptoms. The total score was used to assess the mothers’ mental health. The measure has been shown to have good construct validity and clinical sensitivity [18, 19]. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the GHQ Total score was 0.86.

3. Results

Assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity were examined. Sample characteristics were assessed using independent t-test and chi-square for comparability between the intervention and wait list control conditions at baseline. There were no significant differences between the intervention and waitlist participants on any socio-demographic or outcome variable, suggesting the randomization had resulted in comparable groups. The means

Disruptive behavior problems in childhood are characterized by aggressive, oppositional defiant, and hyperactive behaviors [1] and can increase the risk for violence and substance abuse in adolescence and adulthood [2]. These behavior problems are affected by many factors including deficits in children’s emotional competence, especially problems in emotion regulation [3]. Emotion socialization is one of the principal factors contributing to children’s emotional competence [4].

Emotion socialization practices are determined by the beliefs of parents about their own expression and children’s negative emotions [5]. Socialization is influenced by the way parents regulate and express their emotions, whether they coach their children in understanding and regulating emotion, and their reactions to children’s negative emotion expression [4]. Emotion coaching and emotion dismissing are two emotion socialization parenting styles described by Gottman [5]. Emotion coaching parenting behaviors, such as validating children’s emotions, develop the competencies children need for managing their negative emotions [6]. In contrast, emotion dismissing parenting behaviors, such as minimizing children’s emotions, can be an obstacle for children learning to regulate their negative emotions [5].

The Tuning in to Kids (TIK) parenting program is an intervention that targets emotion socialization [7]. TIK is a group intervention for parents of preschoolers and has been developed in Australia. TIK concentrates on parental emotion socialization and helps parents learn emotion coaching to enhance children’s behavior and emotion regulation. In addition, the program targets the parents’ own emotion regulation so as to make parenting more responsive and less reactive. As a result, it is expected that parent–child relationships will improve, and child disruptive behaviors will be prevented or reduced [5, 8].

Different research studies have proven the efficacy of the TIK program in community and clinical samples of preschool children [9, 10]. For example, Havighurst and colleagues [11] evaluated TIK as an early intervention for preschool children with behavior problems and found that parents in the intervention condition reported less emotion dismissiveness and child behavior problems as well as greater emotion coaching and empathy.

Objectives

Behavioral parenting programs are the most commonly used approach to address child disruptive behavior problems in Iran. Emotion-focused interventions such as TIK are relatively new in the parenting literature, and the current study aimed to assess the efficacy of this promising approach on parenting practices and child behavior. This study is the first investigation of TIK used in Iran. It was hypothesized that the TIK program would increase parent emotion socialization and reduce child behavior problems.

2. Methods

Participants and sampling

Participants were 3-6 years old children with behavior problems who attended preschools in Tehran during 2016. The sample consisted of 54 mothers (Mean age=34.21 years, SD=4.79) with at least one child between 3.0 and 5.11 years of age (Mean age=4.33, SD=0.93) recruited from 18 preschools in diverse lower- to upper-class socio-economic areas of Tehran. All children (n=359) whose mothers expressed interest in attending a parenting program and participating in the research were screened using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) [12].

Inclusion criteria were having a 3-6 years old child with behavior problem. Exclusion criteria included a diagnosis of intellectual disability or pervasive developmental disorder. Children (N=74: 21%) with a T score of 65 or higher on the externalizing subscale of the CBCL were categorized as at risk and selected for this study. Of the 74 at-risk children, 54 children met the inclusion criteria and their mothers were interested in participating in the parenting program. As six mothers did not complete the program, final analyses were conducted with 48 participants. All mothers were married. Maternal education ranged from non-completion of high school (2.1%) to diploma (25%) and university education (73%). With regard to employment, 87.5% of mothers were not in paid work, and 12.5% were employed. Family income ranged from less than one million Tomans to over 5 million Tomans. All children lived with both parents, and 48% of children had two or more siblings.

Procedure

The research was a pre-test and post-test, quasi-experimental study that included a control group and baseline, immediate post-intervention, and 3-month follow-up assessments. Prior to starting the study, approval was obtained from the research ethics committee of the University of Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, and all mothers gave informed consent. Once recruited, the mothers were randomized into TIK intervention (n=27) or waitlist control condition (n=27) using a random number table. Mothers in the intervention group started the TIK program shortly after baseline assessment. The TIK program was offered to mothers in the waitlist control after the follow-up assessment was conducted. Mothers completed questionnaires about their child’s behavior problems as well as their emotion socialization and mental health. Two mothers from the intervention group and four mothers from control group dropped out at post-intervention and follow-up.

The TIK program is a structured, manualized group parenting program that was led by two facilitators (PhD student), trained by the TIK first author (Havighurst) who also supervised the intervention delivery. Fidelity checklists were completed after each session to ensure the program was delivered according to the manual. The facilitators delivered the TIK program for 120 minutes per week for six weeks. Two booster sessions were offered at two-monthly intervals after the initial six weeks. Three months after the last booster session, follow-up data were collected. The five steps of emotion coaching parenting [5] were taught via a set of psycho-education materials, role plays, DVD demonstrations, and home activities.

The focus of sessions was for parents to become aware of emotions, reflect and label emotions, and empathize with their child. TIK addresses fears and worries, anger, and problem solving for the children, and teaches emotion regulation strategies for parents including relaxation, self-care, and managing anger. Psycho-education including information about children’s emotional competence and the way different parenting styles contribute to the development of emotion regulation skills were provided. Parental meta-emotion, including parent’s family of origin experiences with emotions, was explored. Mothers were also encouraged to allocate a specific time for discussion about negative emotions with their child.

Measures

Child Behavior Checklist

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) [12] for preschool children was used to screen preschoolers for behavior problems. The CBCL has three domains: internalizing, externalizing, and total problems. CBCL is an appropriate measure for screening child behavior problems. “Subclinical” (T-score ≥60) and “clinical” (T-score ≥63) cut-off points have been defined [12]. In the current study, a T-score ≥65 on externalizing was used to select a sample at-risk. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha for externalizing scores was 0.89.

Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory

The Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (ECBI) [13] is a 36-item parent-report scale of behavior problems and was used in this study as an outcome measure. This psychometrically strong inventory has two components: an Intensity score, which measures the frequency of behaviors, and the Problem score, which determines whether the behavior is a problem or not. Many studies have used the ECBI and shown it to have excellent internal consistency, construct validity, and convergent validity [14]. The problem score with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92 was used in the current study as a parent-rated measure of child behavior problems.

Parent Emotional Style Questionnaire

The Parent Emotional Style Questionnaire (PESQ) [15] is a 21- item two-factor (Emotion Coaching and Emotion Dismissing) scale that was adapted from the 14-item Maternal Emotional Styles Questionnaire [16] to measure parent-reported emotion socialization. Parents rated their beliefs about child’s worry, anger and sadness. Cronbach’s alpha for Emotion Coaching ranged from 0.78 to 0.84 and for Emotion Dismissing ranged from 0.82 to 0.86 [11]. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for Emotion Dismissing was 0.83 and for Emotion Coaching was 0.76.

General Health Questionnaire

The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) [17] is a 28 item questionnaire with subscales of Severe Depression, Anxiety and Insomnia, Social Dysfunction, and Somatic Symptoms. The total score was used to assess the mothers’ mental health. The measure has been shown to have good construct validity and clinical sensitivity [18, 19]. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the GHQ Total score was 0.86.

3. Results

Assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity were examined. Sample characteristics were assessed using independent t-test and chi-square for comparability between the intervention and wait list control conditions at baseline. There were no significant differences between the intervention and waitlist participants on any socio-demographic or outcome variable, suggesting the randomization had resulted in comparable groups. The means

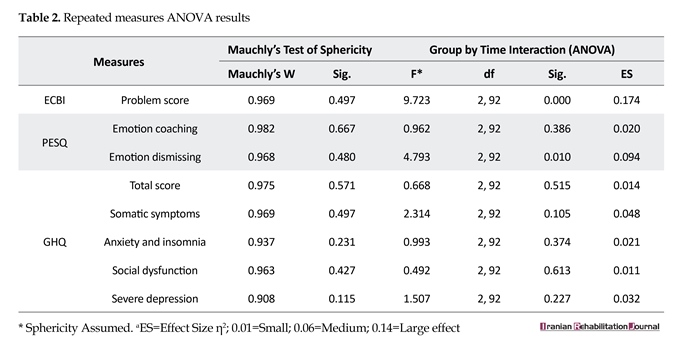

and standard errors for all variables are reported in Table 1. Repeated measures ANOVA were used to analyze the impact of the TIK program on mothers and children (Table 2). Pairwise comparison was used to examine at what time change occurred (i.e., either pre-intervention to post-intervention or post-intervention to follow-up). Confidence intervals for pairwise comparison can be seen in the three right hand columns of Table 1. Effect sizes were also calculated using partial eta square (Table 2).

Repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant interaction between condition and time for ECBI problem scores (Table 2), with a reduction for children in the intervention group at post-intervention that continued at follow-up (Table 1). There was also a significant interaction between condition and time for Emotion Dismissing (Table 2). Mothers in the intervention condition reported being less dismissive, whereas mothers in the control condition did not change. Despite the fact that there were no statistically significant differences between the two conditions on the Emotion Coaching subscale, mothers in the intervention condition showed a slight but not significant increase in emotion coaching. There were no statistically significant differences between conditions

Repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant interaction between condition and time for ECBI problem scores (Table 2), with a reduction for children in the intervention group at post-intervention that continued at follow-up (Table 1). There was also a significant interaction between condition and time for Emotion Dismissing (Table 2). Mothers in the intervention condition reported being less dismissive, whereas mothers in the control condition did not change. Despite the fact that there were no statistically significant differences between the two conditions on the Emotion Coaching subscale, mothers in the intervention condition showed a slight but not significant increase in emotion coaching. There were no statistically significant differences between conditions

for the total score or subscales of the GHQ. Mothers who attended the intervention showed a slight reduction in GHQ total scores that were not significant (Table 1).

4. Discussion

The TIK program targets parent emotion socialization by addressing beliefs about negative emotions and teaching the five steps of emotion coaching. The goal of this study was to investigate the efficacy of the TIK program with mothers of preschoolers with behavior problems in Iran. The evaluation showed that mothers who attended TIK were significantly less emotion dismissing with a moderate effect size, a finding consistent with original studies of the TIK program in Australia [11, 15]. Emotion dismissing parenting has been found to be detrimental to children’s emotional and behavioral development [20], and so, reductions in this aspect of parenting are important. In contrast to community samples [15] and consistent with previous clinical evaluations [9, 11] of TIK, in the current study, mothers did not report any increase in emotion coaching. Previous studies have shown the expectancy bias affects parents’ reports on emotion socialization questionnaires, especially emotion socialization beliefs. Observation measures would have improved reliability of the evaluation [15, 21].

According to the research literature, there is a link between emotion dismissive parenting and child disruptive behaviors [3, 4, 20, 22]. While the TIK program is an emotion-focused intervention and used few behavioral strategies, mothers receiving TIK reported significant reductions in their children’s behavior problems with a large effect size. It has been shown that different versions of TIK reduce behavior problems in a range of age groups including toddlers [21], preschoolers [23], middle childhood and adolescence [24] with normal [10, 15, 25] and clinical [9, 11, 26] samples. Interventions that aim to reduce children’s disruptive behaviors usually use behavioral parenting strategies.

As TIK does not focus on behavior management, reduction in disruptive behavior problems is a significant outcome. One study comparing TIK and a behavioral parenting approach (Triple P) found both programs were associated with significant reductions in children’s disruptive behaviors [26]. The current study supports the theoretical model that parenting interventions, which improve parent emotion socialization, can affect children’s behavior. It has been found that reducing emotion dismissing and increasing empathy can also directly enhance children’s prosocial behavior [27]. The current study is also consistent with previous research demonstrating that behavioral interventions are not the only method of enhancing child behavior; emotion-focused programs are also effective.

TIK teaches parents to improve their anger management, emotional self-care and responses to their own emotions. In the current study, mothers did not report any changes in their well-being. This may be because the main focus of TIK is on the child’s emotions. It is possible that mothers first change their responses to children’s emotions rather than changing responses to their own emotions. It may take longer for this learning to generalize to improvements in their own emotion regulation.

One of the main limitations of the current study concerns parent-report measures. Evaluating parent emotion socialization and children’s behavior across contexts and raters using teacher report and observation methods would reduce the effect of expectancy bias and offer a more reliable indicator of change. Future studies with observation of children’s behavior are recommended. In the current study, we only used mothers’ reports on their parenting. The results would be strengthened with a larger sample of participants that involved both parents. We assessed changes in mother and child outcomes at 3-month follow-up. Extending follow-up for a longer period to the child starting school would provide further efficacy of the program in assisting children with this important transition.

5. Conclusion

The TIK program is a new Australian group intervention for parents of preschool children being tested for the first time in Iran. TIK focuses on parental emotion socialization beliefs and practices and teaches parents emotion coaching to improve children’s emotion regulation and behavior. The findings of this pilot trial suggest TIK appears to be a promising parenting intervention for mothers and children with disruptive behavior problems, offering a useful addition to programs usually used in Iran.

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on corresponding author’s PhD dissertation. The dissertation title is "The patterns of mother- child emotional interaction and the Effectiveness of the Tuning in to Kids on mothers and Preschoolers with behavior problems" that has been submitted in Department of Clinical Psychology, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences of Tehran. We thank the staff from all preschools for assisting in recruitment and intervention delivery. We also thank to all the mothers who participated in the current study.

Conflict of Interest

The last author (Havighurst) declares a conflicts of interest in that she may benefit from the positive report of the Tuning in to Kids program.

References

[1]Breitenstein SM, Hill C, Gross D. Understanding disruptive behavior problems in preschool children. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2009; 24(1):3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2007.10.007

[2]Keenan K, Boeldt D, Chen D, Coyne C, Donald R, Duax J, et al. Predictive validity of DSM-IV oppositional defiant and conduct disorders in clinically referred preschoolers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010; 52(1):47–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02290.x

[3]Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Terranova AM, Kithakye M. Concurrent and longitudinal links between children’s externalizing behavior in school and observed anger regulation in the mother–child dyad. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2009; 32(1):48–56. doi: 10.1007/s10862-009-9166-9

[4]Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL. Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry. 1998; 9(4):241–73. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1

[5]Gottman JM, Katz LF, Hooven C. Meta-emotion: How families communicate emotionally. Hove: Psychology Press; 1997.

[6]Lunkenheimer ES, Shields AM, Cortina KS. Parental emotion coaching and dismissing in family interaction. Social Development. 2007; 16(2):232–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00382.x

[7]Havighurst S, Harley A. Tuning in to kids: Emotionally intelligent parenting: Program manual. Melbourne: University of Melbourne; 2007.

[8]Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Myers SS, Robinson LR. The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development. 2007; 16(2):361–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x

[9]Havighurst SS, Duncombe M, Frankling E, Holland K, Kehoe C, Stargatt R. An emotion-focused early intervention for children with emerging conduct problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014; 43(4):749–60. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9944-z

[10]Havighurst SS, Wilson KR, Harley AE, Prior MR. Tuning in to kids: An emotion-focused parenting program-initial findings from a community trial. Journal of Community Psychology. 2009; 37(8):1008–23. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20345

[11]Havighurst SS, Wilson KR, Harley AE, Kehoe C, Efron D, Prior MR. “Tuning into kids”: Reducing young children’s behavior problems using an emotion coaching parenting program. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2012; 44(2):247–64. Doi: 10.1007/s10578-012-0322-1

[12]Aschenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manuale for the ASEBA preschoole forms and profiles. Burlington: Research Center for Children, Youth and Families; 2000.

[13]Eyberg SM, Robinson EA. Conduct problem behavior: Standardization of a behavioral rating. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1983; 12(3):347–54. doi: 10.1080/15374418309533155

[14]Burns GL, Patterson DR. Factor structure of the eyberg child behavior inventory: Unidimensional or multidimensional measure of disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1991; 20(4):439–44. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2004_13

[15]Havighurst SS, Wilson KR, Harley AE, Prior MR, Kehoe C. Tuning in to kids: Improving emotion socialization practices in parents of preschool children - findings from a community trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010; 51(12):1342–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02303.x

[16]Lagace-Seguin DG, Coplan RJ. Maternal emotional styles and child social adjustment: Assessment, correlates, outcomes and goodness of fit in early childhood. Social Development. 2005; 14(4):613–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2005.00320.x

[17]Goldberg D, Williams P. A user's guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windso: NFER Nelson; 1988.

[18]Taghavi SMR. [Validity and reliability of the general health questionnaire (GHQ-28) in college students of Shiraz University (Persian)]. Journal of Psychology. 2002; 5(4):381-98.

[19]Raphael B, Lundin T, McFarlane C. A research method for the study of psychological and psychiatric aspects of disaster. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1989; 80(S353):1–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb03041.x

[20]Duncombe ME, Havighurst SS, Holland KA, Frankling EJ. The contribution of parenting practices and parent emotion factors in children at risk for disruptive behavior disorders. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2012; 43(5):715–33. doi: 10.1007/s10578-012-0290-5

[21]Lauw MSM, Havighurst SS, Wilson KR, Harley AE, Northam EA. Improving parenting of toddlers’ emotions using an emotion coaching parenting program: A pilot study oftuning in to toddlers. Journal of Community Psychology. 2014; 42(2):169–75. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21602

[22]Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Murphy BC. Parents' reactions to children's negative emotions: Relations to children's social competence and comforting behavior. Child Development. 1996; 67(5):2227-47. doi: 10.2307/1131620

[23]Wilson KR, Havighurst SS, Kehoe C, Harley AE. Dads tuning in to kids: Preliminary evaluation of a fathers' parenting program. Family Relations. 2016; 65(4):535-49. doi: 10.1111/fare.12216

[24]Havighurst SS, Kehoe CE, Harley AE. Tuning in to teens: Improving parental responses to anger and reducing youth externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Adolescence. 2015; 42:148–58. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.04.005

[25]Havighurst SS, Harley A, Prior M. Building preschool children's emotional competence: A parenting program. Early Education & Development. 2004; 15(4):423-48. doi: 10.1207/s15566935eed1504_5

[26]Duncombe ME, Havighurst SS, Kehoe CE, Holland KA, Frankling EJ, Stargatt R. Comparing an emotion and a behavior focused parenting program as part of a multsystemic intervention for child conduct problems. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2014; 45(3):320–34. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.963855

[27]Schaffer M, Clark S, Jeglic EL. The role of empathy and parenting style in the development of antisocial behaviors. Crime & Delinquency. 2008; 55(4):586–99. doi: 10.1177/0011128708321359

4. Discussion

The TIK program targets parent emotion socialization by addressing beliefs about negative emotions and teaching the five steps of emotion coaching. The goal of this study was to investigate the efficacy of the TIK program with mothers of preschoolers with behavior problems in Iran. The evaluation showed that mothers who attended TIK were significantly less emotion dismissing with a moderate effect size, a finding consistent with original studies of the TIK program in Australia [11, 15]. Emotion dismissing parenting has been found to be detrimental to children’s emotional and behavioral development [20], and so, reductions in this aspect of parenting are important. In contrast to community samples [15] and consistent with previous clinical evaluations [9, 11] of TIK, in the current study, mothers did not report any increase in emotion coaching. Previous studies have shown the expectancy bias affects parents’ reports on emotion socialization questionnaires, especially emotion socialization beliefs. Observation measures would have improved reliability of the evaluation [15, 21].

According to the research literature, there is a link between emotion dismissive parenting and child disruptive behaviors [3, 4, 20, 22]. While the TIK program is an emotion-focused intervention and used few behavioral strategies, mothers receiving TIK reported significant reductions in their children’s behavior problems with a large effect size. It has been shown that different versions of TIK reduce behavior problems in a range of age groups including toddlers [21], preschoolers [23], middle childhood and adolescence [24] with normal [10, 15, 25] and clinical [9, 11, 26] samples. Interventions that aim to reduce children’s disruptive behaviors usually use behavioral parenting strategies.

As TIK does not focus on behavior management, reduction in disruptive behavior problems is a significant outcome. One study comparing TIK and a behavioral parenting approach (Triple P) found both programs were associated with significant reductions in children’s disruptive behaviors [26]. The current study supports the theoretical model that parenting interventions, which improve parent emotion socialization, can affect children’s behavior. It has been found that reducing emotion dismissing and increasing empathy can also directly enhance children’s prosocial behavior [27]. The current study is also consistent with previous research demonstrating that behavioral interventions are not the only method of enhancing child behavior; emotion-focused programs are also effective.

TIK teaches parents to improve their anger management, emotional self-care and responses to their own emotions. In the current study, mothers did not report any changes in their well-being. This may be because the main focus of TIK is on the child’s emotions. It is possible that mothers first change their responses to children’s emotions rather than changing responses to their own emotions. It may take longer for this learning to generalize to improvements in their own emotion regulation.

One of the main limitations of the current study concerns parent-report measures. Evaluating parent emotion socialization and children’s behavior across contexts and raters using teacher report and observation methods would reduce the effect of expectancy bias and offer a more reliable indicator of change. Future studies with observation of children’s behavior are recommended. In the current study, we only used mothers’ reports on their parenting. The results would be strengthened with a larger sample of participants that involved both parents. We assessed changes in mother and child outcomes at 3-month follow-up. Extending follow-up for a longer period to the child starting school would provide further efficacy of the program in assisting children with this important transition.

5. Conclusion

The TIK program is a new Australian group intervention for parents of preschool children being tested for the first time in Iran. TIK focuses on parental emotion socialization beliefs and practices and teaches parents emotion coaching to improve children’s emotion regulation and behavior. The findings of this pilot trial suggest TIK appears to be a promising parenting intervention for mothers and children with disruptive behavior problems, offering a useful addition to programs usually used in Iran.

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on corresponding author’s PhD dissertation. The dissertation title is "The patterns of mother- child emotional interaction and the Effectiveness of the Tuning in to Kids on mothers and Preschoolers with behavior problems" that has been submitted in Department of Clinical Psychology, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences of Tehran. We thank the staff from all preschools for assisting in recruitment and intervention delivery. We also thank to all the mothers who participated in the current study.

Conflict of Interest

The last author (Havighurst) declares a conflicts of interest in that she may benefit from the positive report of the Tuning in to Kids program.

References

[1]Breitenstein SM, Hill C, Gross D. Understanding disruptive behavior problems in preschool children. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2009; 24(1):3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2007.10.007

[2]Keenan K, Boeldt D, Chen D, Coyne C, Donald R, Duax J, et al. Predictive validity of DSM-IV oppositional defiant and conduct disorders in clinically referred preschoolers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010; 52(1):47–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02290.x

[3]Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Terranova AM, Kithakye M. Concurrent and longitudinal links between children’s externalizing behavior in school and observed anger regulation in the mother–child dyad. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2009; 32(1):48–56. doi: 10.1007/s10862-009-9166-9

[4]Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL. Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry. 1998; 9(4):241–73. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1

[5]Gottman JM, Katz LF, Hooven C. Meta-emotion: How families communicate emotionally. Hove: Psychology Press; 1997.

[6]Lunkenheimer ES, Shields AM, Cortina KS. Parental emotion coaching and dismissing in family interaction. Social Development. 2007; 16(2):232–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00382.x

[7]Havighurst S, Harley A. Tuning in to kids: Emotionally intelligent parenting: Program manual. Melbourne: University of Melbourne; 2007.

[8]Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Myers SS, Robinson LR. The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development. 2007; 16(2):361–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x

[9]Havighurst SS, Duncombe M, Frankling E, Holland K, Kehoe C, Stargatt R. An emotion-focused early intervention for children with emerging conduct problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014; 43(4):749–60. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9944-z

[10]Havighurst SS, Wilson KR, Harley AE, Prior MR. Tuning in to kids: An emotion-focused parenting program-initial findings from a community trial. Journal of Community Psychology. 2009; 37(8):1008–23. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20345

[11]Havighurst SS, Wilson KR, Harley AE, Kehoe C, Efron D, Prior MR. “Tuning into kids”: Reducing young children’s behavior problems using an emotion coaching parenting program. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2012; 44(2):247–64. Doi: 10.1007/s10578-012-0322-1

[12]Aschenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manuale for the ASEBA preschoole forms and profiles. Burlington: Research Center for Children, Youth and Families; 2000.

[13]Eyberg SM, Robinson EA. Conduct problem behavior: Standardization of a behavioral rating. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1983; 12(3):347–54. doi: 10.1080/15374418309533155

[14]Burns GL, Patterson DR. Factor structure of the eyberg child behavior inventory: Unidimensional or multidimensional measure of disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1991; 20(4):439–44. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2004_13

[15]Havighurst SS, Wilson KR, Harley AE, Prior MR, Kehoe C. Tuning in to kids: Improving emotion socialization practices in parents of preschool children - findings from a community trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010; 51(12):1342–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02303.x

[16]Lagace-Seguin DG, Coplan RJ. Maternal emotional styles and child social adjustment: Assessment, correlates, outcomes and goodness of fit in early childhood. Social Development. 2005; 14(4):613–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2005.00320.x

[17]Goldberg D, Williams P. A user's guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windso: NFER Nelson; 1988.

[18]Taghavi SMR. [Validity and reliability of the general health questionnaire (GHQ-28) in college students of Shiraz University (Persian)]. Journal of Psychology. 2002; 5(4):381-98.

[19]Raphael B, Lundin T, McFarlane C. A research method for the study of psychological and psychiatric aspects of disaster. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1989; 80(S353):1–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb03041.x

[20]Duncombe ME, Havighurst SS, Holland KA, Frankling EJ. The contribution of parenting practices and parent emotion factors in children at risk for disruptive behavior disorders. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2012; 43(5):715–33. doi: 10.1007/s10578-012-0290-5

[21]Lauw MSM, Havighurst SS, Wilson KR, Harley AE, Northam EA. Improving parenting of toddlers’ emotions using an emotion coaching parenting program: A pilot study oftuning in to toddlers. Journal of Community Psychology. 2014; 42(2):169–75. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21602

[22]Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Murphy BC. Parents' reactions to children's negative emotions: Relations to children's social competence and comforting behavior. Child Development. 1996; 67(5):2227-47. doi: 10.2307/1131620

[23]Wilson KR, Havighurst SS, Kehoe C, Harley AE. Dads tuning in to kids: Preliminary evaluation of a fathers' parenting program. Family Relations. 2016; 65(4):535-49. doi: 10.1111/fare.12216

[24]Havighurst SS, Kehoe CE, Harley AE. Tuning in to teens: Improving parental responses to anger and reducing youth externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Adolescence. 2015; 42:148–58. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.04.005

[25]Havighurst SS, Harley A, Prior M. Building preschool children's emotional competence: A parenting program. Early Education & Development. 2004; 15(4):423-48. doi: 10.1207/s15566935eed1504_5

[26]Duncombe ME, Havighurst SS, Kehoe CE, Holland KA, Frankling EJ, Stargatt R. Comparing an emotion and a behavior focused parenting program as part of a multsystemic intervention for child conduct problems. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2014; 45(3):320–34. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.963855

[27]Schaffer M, Clark S, Jeglic EL. The role of empathy and parenting style in the development of antisocial behaviors. Crime & Delinquency. 2008; 55(4):586–99. doi: 10.1177/0011128708321359

Article type: Original Research Articles |

Subject:

Clinical sciences

Received: 2017/07/4 | Accepted: 2017/07/16 | Published: 2017/10/2

Received: 2017/07/4 | Accepted: 2017/07/16 | Published: 2017/10/2

References

1. Breitenstein SM, Hill C, Gross D. Understanding disruptive behavior problems in preschool children. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2009; 24(1):3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2007.10.007 [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2007.10.007]

2. Keenan K, Boeldt D, Chen D, Coyne C, Donald R, Duax J, et al. Predictive validity of DSM-IV oppositional defiant and conduct disorders in clinically referred preschoolers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010; 52(1):47–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02290.x [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02290.x]

3. Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Terranova AM, Kithakye M. Concurrent and longitudinal links between children's externalizing behavior in school and observed anger regulation in the mother–child dyad. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2009; 32(1):48–56. doi: 10.1007/s10862-009-9166-9 [DOI:10.1007/s10862-009-9166-9]

4. Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL. Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry. 1998; 9(4):241–73. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1 [DOI:10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1]

5. Gottman JM, Katz LF, Hooven C. Meta-emotion: How families communicate emotionally. Hove: Psychology Press; 1997.

6. Lunkenheimer ES, Shields AM, Cortina KS. Parental emotion coaching and dismissing in family interaction. Social Development. 2007; 16(2):232–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00382.x [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00382.x]

7. Havighurst S, Harley A. Tuning in to kids: Emotionally intelligent parenting: Program manual. Melbourne: University of Melbourne; 2007.

8. Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Myers SS, Robinson LR. The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development. 2007; 16(2):361–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x]

9. Havighurst SS, Duncombe M, Frankling E, Holland K, Kehoe C, Stargatt R. An emotion-focused early intervention for children with emerging conduct problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014; 43(4):749–60. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9944-z [DOI:10.1007/s10802-014-9944-z]

10. Havighurst SS, Wilson KR, Harley AE, Prior MR. Tuning in to kids: An emotion-focused parenting program-initial findings from a community trial. Journal of Community Psychology. 2009; 37(8):1008–23. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20345 [DOI:10.1002/jcop.20345]

11. Havighurst SS, Wilson KR, Harley AE, Kehoe C, Efron D, Prior MR. "Tuning into kids": Reducing young children's behavior problems using an emotion coaching parenting program. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2012; 44(2):247–64. Doi: 10.1007/s10578-012-0322-1 [DOI:10.1007/s10578-012-0322-1]

12. Aschenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manuale for the ASEBA preschoole forms and profiles. Burlington: Research Center for Children, Youth and Families; 2000.

13. Eyberg SM, Robinson EA. Conduct problem behavior: Standardization of a behavioral rating. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1983; 12(3):347–54. doi: 10.1080/15374418309533155 [DOI:10.1080/15374418309533155]

14. Burns GL, Patterson DR. Factor structure of the eyberg child behavior inventory: Unidimensional or multidimensional measure of disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1991; 20(4):439–44. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2004_13 [DOI:10.1207/s15374424jccp2004_13]

15. Havighurst SS, Wilson KR, Harley AE, Prior MR, Kehoe C. Tuning in to kids: Improving emotion socialization practices in parents of preschool children - findings from a community trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010; 51(12):1342–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02303.x [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02303.x]

16. Lagace-Seguin DG, Coplan RJ. Maternal emotional styles and child social adjustment: Assessment, correlates, outcomes and goodness of fit in early childhood. Social Development. 2005; 14(4):613–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2005.00320.x [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2005.00320.x]

17. Goldberg D, Williams P. A user's guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windso: NFER Nelson; 1988.

18. Taghavi SMR. [Validity and reliability of the general health questionnaire (GHQ-28) in college students of Shiraz University (Persian)]. Journal of Psychology. 2002; 5(4):381-98.

19. Raphael B, Lundin T, McFarlane C. A research method for the study of psychological and psychiatric aspects of disaster. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1989; 80(S353):1–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb03041.x [DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb03041.x]

20. Duncombe ME, Havighurst SS, Holland KA, Frankling EJ. The contribution of parenting practices and parent emotion factors in children at risk for disruptive behavior disorders. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2012; 43(5):715–33. doi: 10.1007/s10578-012-0290-5 [DOI:10.1007/s10578-012-0290-5]

21. Lauw MSM, Havighurst SS, Wilson KR, Harley AE, Northam EA. Improving parenting of toddlers' emotions using an emotion coaching parenting program: A pilot study oftuning in to toddlers. Journal of Community Psychology. 2014; 42(2):169–75. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21602 [DOI:10.1002/jcop.21602]

22. Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Murphy BC. Parents' reactions to children's negative emotions: Relations to children's social competence and comforting behavior. Child Development. 1996; 67(5):2227-47. doi: 10.2307/1131620 [DOI:10.2307/1131620]

23. Wilson KR, Havighurst SS, Kehoe C, Harley AE. Dads tuning in to kids: Preliminary evaluation of a fathers' parenting program. Family Relations. 2016; 65(4):535-49. doi: 10.1111/fare.12216 [DOI:10.1111/fare.12216]

24. Havighurst SS, Kehoe CE, Harley AE. Tuning in to teens: Improving parental responses to anger and reducing youth externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Adolescence. 2015; 42:148–58. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.04.005 [DOI:10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.04.005]

25. Havighurst SS, Harley A, Prior M. Building preschool children's emotional competence: A parenting program. Early Education & Development. 2004; 15(4):423-48. doi: 10.1207/s15566935eed1504_5 [DOI:10.1207/s15566935eed1504_5]

26. Duncombe ME, Havighurst SS, Kehoe CE, Holland KA, Frankling EJ, Stargatt R. Comparing an emotion and a behavior focused parenting program as part of a multsystemic intervention for child conduct problems. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2014; 45(3):320–34. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.963855 [DOI:10.1080/15374416.2014.963855]

27. Schaffer M, Clark S, Jeglic EL. The role of empathy and parenting style in the development of antisocial behaviors. Crime & Delinquency. 2008; 55(4):586–99. doi: 10.1177/0011128708321359 [DOI:10.1177/0011128708321359]

Send email to the article author