Volume 16, Issue 2 (June 2018)

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2018, 16(2): 195-202 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Kwah S B, Abdullahi A. Coping Strategies in People With Spinal Cord Injury: A Qualitative Interviewing. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2018; 16 (2) :195-202

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-845-en.html

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-845-en.html

1- Department of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Allied Health Sciences, College of Health Sciences, Bayero Univerity Kano, Kano, Nigeria.

Full-Text [PDF 564 kb]

(2234 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (5179 Views)

Full-Text: (1432 Views)

1. Introduction

Spinal cord is an important part of the central nervous system majorly concerned with sensorimotor function. When there is damage or injury to the spinal cord, the function of the spinal cord is impaired. This in turn can affect the patients’ functional independence and quality of life [1, 2]. Throughout the world, up to 15-40 million people suffer from Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) [3]. Thus, it is a condition of utmost public health importance as people with SCI may face many challenges with respect to psychological function, physical function and return to work [4-6] and may even be predisposed to committing suicide [7].

Due to the challenges in psychological and physical functioning, people with SCI may often undergo a long-term rehabilitation aimed at improving their foregoing functions so as to achieve possible functional independence and quality of life [8]. However, SCI is a life-shattering event; such patients may be confronted with emotional and psychological challenges on how to come to terms with their injuries and/or disability. Consequently, there could be needs for them to develop certain coping behaviors or strategies, which are means of solving the problems or challenges confronting them due to the SCI [9]. Developing these coping strategies is essential for having less psychological distress and hopelessness during a stressful life event [10]. Additionally, these may help with life adjustment and social reintegration following SCI [11, 12].

There are many strategies for coping reported in the literature. They include positive cognitive restructuring, seeking support, problem-solving, distraction and escape/ avoidance [13, 14]. Positive cognitive restructuring refers to devising means of seeing one’s stressful condition in a positive, an optimistic or a good way [14]. Problem-solving refers to making active efforts to correct, modify or improve the stressful condition as opposed to engaging in wishful thinking; it has been reported to be very effective at improving one’s condition when it is employed [15-16]. Seeking support relates to seeking for counsel, emotional support, and so on from a significant other such as a religious leader, spouse, friend, parent, and a professional concerned with one’s problem [14]. Distraction, as opposed to the problem-solving strategy, is a passive way of coping through concentration on activities such as reading, playing, listening to music, and so on in order to take one’s mind away from the condition. Escape/ avoidance refers to taking away one’s thoughts and behavior away from the condition so as to try not to think or do anything that has to do with the condition [16].

In people with SCI, almost all the above strategies in one form or the other have been employed [17, 18]. In an exploratory study, Babamohamadi and colleagues reported themes such as seeking help from religious beliefs, hope and making efforts towards independence and self-care as the coping strategies used by people with SCI in Iran [17, 19]. In contrast, in the UK, Austria, Germany and Switzerland, acceptance is majorly used as a coping strategy [13]. When the most effective coping strategies for a given group of individuals are known, formal and informal caregivers should do their best in helping to reinforce those strategies [19]. However, the strategies used for coping by people with SCI in a Nigerian population seem not to be previously reported. The aim of this study is to explore the coping strategies used by people with SCI in a Nigerian population.

2. Methods

The study design is qualitative interviewing exploring the strategies used by patients with SCI patients in coping with their condition. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of Kano State Ministry of Health (for Murtala Muhammad Specialist Hospital) and National Orthopedics Hospital, Dala, Kano.

The population of this study was SCI patients in National Orthopedic Hospital, Dala (NOHD), Kano, Murtala Muhammad Specialist Hospital (MMSH), Kano, and possibly those to be gotten outside of the hospitals through snowballing. Purposive sampling technique was used for the selection of the study participants. For the sample size, the study used the number of participants available who signed informed consent forms since there are no hard and fast rules for sample size in qualitative research [20]. The inclusion criteria used in the study were: SCI patients who are ≥18 years and ≥1 year since the SCI (we assumed that by then the patients must have started adapting and strategized ways to cope with the injury). However, patients were excluded if they have a significant cognitive impairment (Mini-mental state examination scores ≥24).

The data collection instruments used in the study are demographic information data sheet, a qualitative interview guide, mini-mental state examination scale, pen and a notebook/pad, and a voice recorder. The qualitative interview guide consists of the following question: What strategies did you use to cope with SCI? Probing technique was also used to elicit clear responses from the participants where possible. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scale was used to assess the mental status of patients. It comprises of 11 items, which measure five cognitive domains that include orientation, registration, attention, calculation and language [21]. The scale has 30 points as its maximum score. A score of ≥25 points indicates normal cognition. However, a score of ≤9 points indicates severe cognitive impairment; a score of 10-20 points indicates moderate cognitive impairment; and a score of 21-24 points indicates mild cognitive impairment [22].

The demographic data obtained were analyzed using descriptive statistics of table, frequency and percentages, and the data from the interview were transcribed, coded and analyzed using thematic (content) analysis.

3. Result

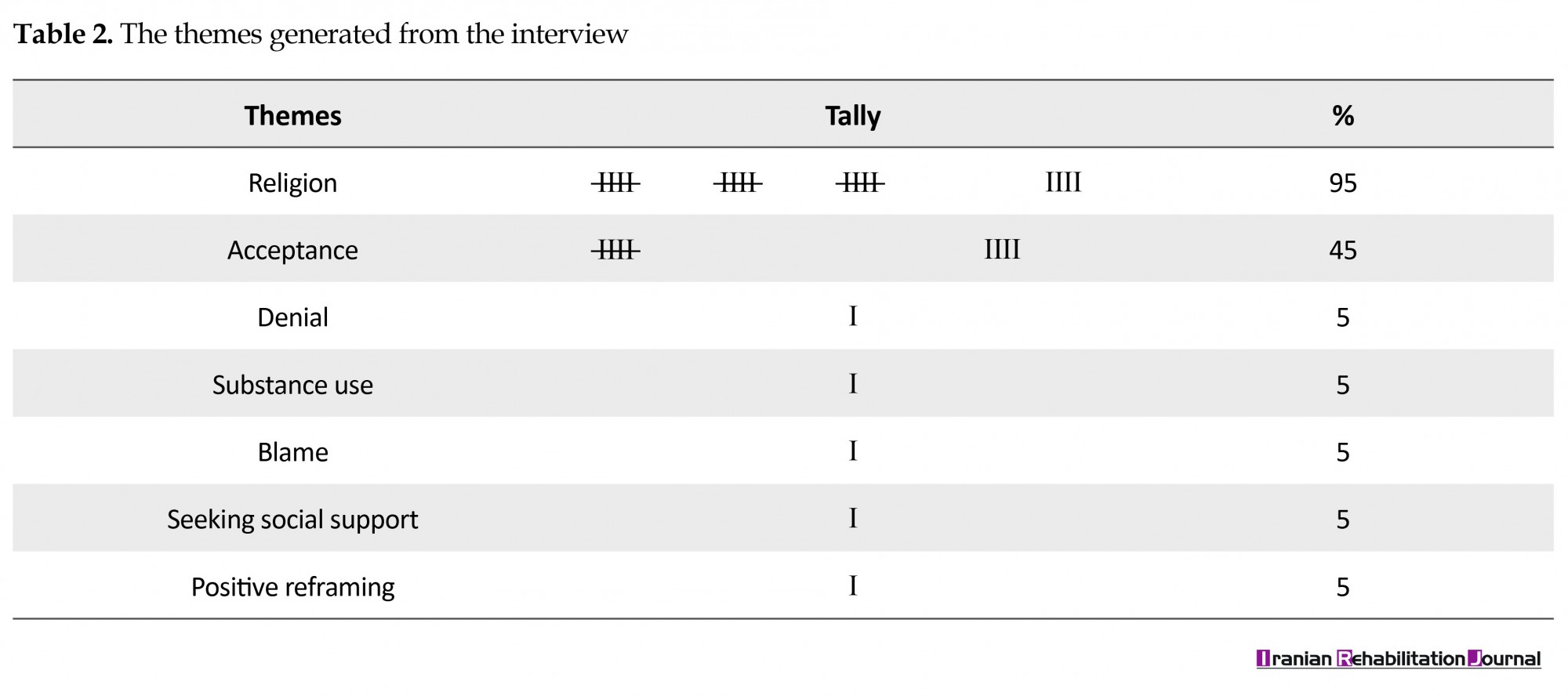

There were 20 SCI patients who participated in the study with age range of 19-23 years. The details of the demographic characteristics of the study participants including mean age, the cause of the SCI, the level of the SCI, grade of the SCI using ASIA scale, and the presence of any co-morbid conditions are presented in Table 1. Following the transcription and coding of the data obtained from the qualitative interview, several themes were generated. The themes are religion, acceptance, positive reframing, denial, seeking social support, and substance use. The characteristics of the generated themes are presented in Table 2.

Spinal cord is an important part of the central nervous system majorly concerned with sensorimotor function. When there is damage or injury to the spinal cord, the function of the spinal cord is impaired. This in turn can affect the patients’ functional independence and quality of life [1, 2]. Throughout the world, up to 15-40 million people suffer from Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) [3]. Thus, it is a condition of utmost public health importance as people with SCI may face many challenges with respect to psychological function, physical function and return to work [4-6] and may even be predisposed to committing suicide [7].

Due to the challenges in psychological and physical functioning, people with SCI may often undergo a long-term rehabilitation aimed at improving their foregoing functions so as to achieve possible functional independence and quality of life [8]. However, SCI is a life-shattering event; such patients may be confronted with emotional and psychological challenges on how to come to terms with their injuries and/or disability. Consequently, there could be needs for them to develop certain coping behaviors or strategies, which are means of solving the problems or challenges confronting them due to the SCI [9]. Developing these coping strategies is essential for having less psychological distress and hopelessness during a stressful life event [10]. Additionally, these may help with life adjustment and social reintegration following SCI [11, 12].

There are many strategies for coping reported in the literature. They include positive cognitive restructuring, seeking support, problem-solving, distraction and escape/ avoidance [13, 14]. Positive cognitive restructuring refers to devising means of seeing one’s stressful condition in a positive, an optimistic or a good way [14]. Problem-solving refers to making active efforts to correct, modify or improve the stressful condition as opposed to engaging in wishful thinking; it has been reported to be very effective at improving one’s condition when it is employed [15-16]. Seeking support relates to seeking for counsel, emotional support, and so on from a significant other such as a religious leader, spouse, friend, parent, and a professional concerned with one’s problem [14]. Distraction, as opposed to the problem-solving strategy, is a passive way of coping through concentration on activities such as reading, playing, listening to music, and so on in order to take one’s mind away from the condition. Escape/ avoidance refers to taking away one’s thoughts and behavior away from the condition so as to try not to think or do anything that has to do with the condition [16].

In people with SCI, almost all the above strategies in one form or the other have been employed [17, 18]. In an exploratory study, Babamohamadi and colleagues reported themes such as seeking help from religious beliefs, hope and making efforts towards independence and self-care as the coping strategies used by people with SCI in Iran [17, 19]. In contrast, in the UK, Austria, Germany and Switzerland, acceptance is majorly used as a coping strategy [13]. When the most effective coping strategies for a given group of individuals are known, formal and informal caregivers should do their best in helping to reinforce those strategies [19]. However, the strategies used for coping by people with SCI in a Nigerian population seem not to be previously reported. The aim of this study is to explore the coping strategies used by people with SCI in a Nigerian population.

2. Methods

The study design is qualitative interviewing exploring the strategies used by patients with SCI patients in coping with their condition. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of Kano State Ministry of Health (for Murtala Muhammad Specialist Hospital) and National Orthopedics Hospital, Dala, Kano.

The population of this study was SCI patients in National Orthopedic Hospital, Dala (NOHD), Kano, Murtala Muhammad Specialist Hospital (MMSH), Kano, and possibly those to be gotten outside of the hospitals through snowballing. Purposive sampling technique was used for the selection of the study participants. For the sample size, the study used the number of participants available who signed informed consent forms since there are no hard and fast rules for sample size in qualitative research [20]. The inclusion criteria used in the study were: SCI patients who are ≥18 years and ≥1 year since the SCI (we assumed that by then the patients must have started adapting and strategized ways to cope with the injury). However, patients were excluded if they have a significant cognitive impairment (Mini-mental state examination scores ≥24).

The data collection instruments used in the study are demographic information data sheet, a qualitative interview guide, mini-mental state examination scale, pen and a notebook/pad, and a voice recorder. The qualitative interview guide consists of the following question: What strategies did you use to cope with SCI? Probing technique was also used to elicit clear responses from the participants where possible. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scale was used to assess the mental status of patients. It comprises of 11 items, which measure five cognitive domains that include orientation, registration, attention, calculation and language [21]. The scale has 30 points as its maximum score. A score of ≥25 points indicates normal cognition. However, a score of ≤9 points indicates severe cognitive impairment; a score of 10-20 points indicates moderate cognitive impairment; and a score of 21-24 points indicates mild cognitive impairment [22].

The demographic data obtained were analyzed using descriptive statistics of table, frequency and percentages, and the data from the interview were transcribed, coded and analyzed using thematic (content) analysis.

3. Result

There were 20 SCI patients who participated in the study with age range of 19-23 years. The details of the demographic characteristics of the study participants including mean age, the cause of the SCI, the level of the SCI, grade of the SCI using ASIA scale, and the presence of any co-morbid conditions are presented in Table 1. Following the transcription and coding of the data obtained from the qualitative interview, several themes were generated. The themes are religion, acceptance, positive reframing, denial, seeking social support, and substance use. The characteristics of the generated themes are presented in Table 2.

Description of the generated themes

Theme 1: Religious belief

Religious belief is one of the strategies the participants use for coping with their conditions. In this study, 95% of the participants use religion in different forms to cope with their condition. Below are some examples of the ways patients cope using religion: “I used to travel to long distant places a longtime ago without having any problem. Now that I have this injury, I believe that it is a destiny from God and surely He is going to reward me on that, and I pray to Him to improve my present condition” said participant number 4.

“I believe that God planned this injury to happen to me. So I consider it as a destiny from Him, even though sometimes I consider myself being unimportant because of this injury and I feel like I rather die instead of living this way. However, believing it as a destiny and test from almighty God prevent me from any attempt to kill myself” said participant number 7.

“Due to my old age, I consider this as part of life processes and it is God’s own making so am doing the possible I can to calm myself down so that at the end I would earn God’s reward” said participant number 8.

Theme 2: Acceptance

Accepting the condition is also used for coping with SCI. The following are some ways in which the patients cope: “I used to be a builder by profession and throughout the years I spent in my carrier, I never came across anything dangerous as this. One day I was hit by a collapsing wall and sustained this injury so I consider it as a destiny from God and I often call it a new life and I don’t see it as a problem.” said participant number 5.

“It is already written by God that I am going to have this injury; so it is God’s choice to see me like this. Hence,it is okay for me.” said participant number 6.

Theme 3: Denial

Another way of coping is by denying having the injury. Below are some examples of the way the participants deny: “Taking it as a destiny from God, I believe that am going to be rewarded by Him, even though people say that after SCI one cannot be able to walk again, and I have seen people with such injury before. However, I strongly believe that my own case is special; I am going to walk.” said participant number 2.

Theme 4: Substance use

Substance use was also used for coping with the condition. One of the participants narrated how he used substance as follows: “Of course I believe that the injury is from God. Besides, my brother who owns a medicine shop helps me with some drugs that always help me to feel better.” said participant number 10.

Theme 5: Blame

Blaming someone or something else is another way of coping. One of the participants did his blame in the following way: “It is just wickedness from my co-cattle rearer. He attacked me while I was praying he escaped before my brothers came to my rescue. Though, it’s a destiny from God” said participant number 19.

Theme 6: Seeking social support

Seeking others’ help is another way for coping with the condition. A patient had this to say: “Actually I believe this injury is from God and I do ask people to recite the whole chapters of the holy Quran for me to get well. I also write some verses of the holy Quran on the slate, then wash and drink the water. Now I am looking for a way to raise the money for my rehabilitation” said participant number 1.

Theme 7: Positive re-framing

Staying positive about the condition and its outcomes is a way to cope with the condition. A participant aptly narrated this in the following manner: “I accepted that the injury is a destiny from God and that I cannot escape from the situation. As soon as I feel much better I would go back to my previous business or change a new one because I was once told by a friend that it is hardly for me to walk again” said participant number 3.

4. Discussion

The aim of the study was to find out the coping strategies used by patients with SCI in a Nigerian population. The study generated seven themes: religion, acceptance, denial, substance use, blame, seeking social support, and positive reframing. Although themes for coping strategies across different populations with different cultural backgrounds may be similar [23], the approaches to a particular theme could be different [13, 17-19]. For example, in Europe and America, people with SCI tend to use acceptance more than any other strategy [13, 18]. In contrast, in Iran, which is predominantly a Muslim country, religion is used as the main coping strategy. Similarly, in the present study, religion was used by 95% of the participants, which could be as a result of the fact that 90% of the participants were Muslims.

Even in Europe and America where acceptance was reported to be higher, a substantial percentage of people with SCI still use religion as a coping strategy [13, 18].This shows that individuals with SCI probably see connecting to their religious belief as an integral part of their wellbeing, which can help them to cope well with stressful situations or conditions [24]. Additionally, the use of religion as a coping strategy seems to be another way of accepting their conditions. In the present study, one of the participants stated: “Due to my old age, I consider this as part of life processes and it is God’s own making so am doing the possible I can to calm myself down so that at the end I would earn God’s reward.” Similarly, among Muslim populations, religion is seen as a springboard to deal with many different disease conditions such as epilepsy, depression and other psychiatric conditions and accept that it is the will of God [25-27]. Thus, Muslims may use religion as a way to accept their stressful condition.

In the present study, the least used coping strategies are positive reframing, denial, blame, substance use and seeking social support. The use of these strategies could also possibly be overshadowed by the religious beliefs. One of the creeds of Islam stipulates that Muslims accept destiny whether bad or good [28]. Thus, deeply entrenched religious belief can serve as catalyst for people to solely believe that it is the doing of God [17, 19, 25-27] and, therefore, accept their conditions without denial, blame or use of drugs or substance. According to Gaston-Johansson and colleagues, when people cope well with their conditions, it is less likely for them to resort to negative coping behaviors [10]. Additionally, the sole belief and dependence on the will of God may also undermine seeking social support. Seeking for social support can be because of instrumental support such as advice and assistance and emotional support such as sympathy [29].

Considering the foregoing, seeking for social support also pertains to seeking for assistance or advice and may also hide under the guise of religion. According to Babamohamadi and colleagues, some of their study participants asked people to help pray for them [17]. Similarly, in this study, some participants echoed the same sentiment as aptly mentioned by the following: participant: “Actually I believe this injury is from God and I do ask people to recite the whole chapters of the holy Quran for me to get well. I also write some verses of the holy Quran on the slate, then wash and drink the water. Now I am looking for away to raise the money for my rehabilitation.” said participant number 1. Similarly, in a Christian population, religious activities attendance was associated with the use of scripture to learn about the health or healing and frequency of prayer to get healing [30].

In every society, there are culturally endorsed coping strategies [30], and problems with societal acceptance and support were identified as barriers to the use of a particular coping strategy in Iran [19]. Consequently, none of the study participants reported use of distractions strategy, and this could be because of factors such as cultural interest in leisure activities such as watching films and reading habit, which seem to be less in the community where the study was carried out. Therefore, understanding patient coping strategies are important to help them navigate through the course of their condition. This is because people with SCI may be required to self-manage their condition due to the long-term nature of the condition. However, inability to cope such as with the use of positive reframing can often hinder self-management [31]. Self-management may aid in achieving greater functional independence and quality of life.

5. Conclusion

From the themes generated in the study, religion may be used as a way to accept a stressful condition. Therefore, healthcare professionals and caregivers are required to help reinforce positive coping strategies such as the use of religion and discourage or prevent the use of negative coping strategies such as substance use. The positive coping strategies can help the patients accept their conditions, work towards functional independence, and have a good quality of life. In contrast, the negative coping strategies can endanger patients’ life or predispose them to committing suicide and developing psychological and emotional problems. Additionally, there seems to be a thin line between many different coping strategies such as between religion and acceptance, as this may depend on the nature of one’s religious beliefs. Future studies should look at the possible interdependencies and relationships with demographic characteristics such as gender, age and ethnic background.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The Research Ethics Committees of Kano State Ministry of Health (for Murtala Muhammad Specialist Hospital) and National Orthopaedics Hospital, Dala, Kano, approved this study. All participants gave written informed consent before data collection began.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the patients who participated in the study and the staff at Murtala Muhammad Specialist Hospital and National Orthopaedics Hospital, Dala, Kano.

References

Theme 1: Religious belief

Religious belief is one of the strategies the participants use for coping with their conditions. In this study, 95% of the participants use religion in different forms to cope with their condition. Below are some examples of the ways patients cope using religion: “I used to travel to long distant places a longtime ago without having any problem. Now that I have this injury, I believe that it is a destiny from God and surely He is going to reward me on that, and I pray to Him to improve my present condition” said participant number 4.

“I believe that God planned this injury to happen to me. So I consider it as a destiny from Him, even though sometimes I consider myself being unimportant because of this injury and I feel like I rather die instead of living this way. However, believing it as a destiny and test from almighty God prevent me from any attempt to kill myself” said participant number 7.

“Due to my old age, I consider this as part of life processes and it is God’s own making so am doing the possible I can to calm myself down so that at the end I would earn God’s reward” said participant number 8.

Theme 2: Acceptance

Accepting the condition is also used for coping with SCI. The following are some ways in which the patients cope: “I used to be a builder by profession and throughout the years I spent in my carrier, I never came across anything dangerous as this. One day I was hit by a collapsing wall and sustained this injury so I consider it as a destiny from God and I often call it a new life and I don’t see it as a problem.” said participant number 5.

“It is already written by God that I am going to have this injury; so it is God’s choice to see me like this. Hence,it is okay for me.” said participant number 6.

Theme 3: Denial

Another way of coping is by denying having the injury. Below are some examples of the way the participants deny: “Taking it as a destiny from God, I believe that am going to be rewarded by Him, even though people say that after SCI one cannot be able to walk again, and I have seen people with such injury before. However, I strongly believe that my own case is special; I am going to walk.” said participant number 2.

Theme 4: Substance use

Substance use was also used for coping with the condition. One of the participants narrated how he used substance as follows: “Of course I believe that the injury is from God. Besides, my brother who owns a medicine shop helps me with some drugs that always help me to feel better.” said participant number 10.

Theme 5: Blame

Blaming someone or something else is another way of coping. One of the participants did his blame in the following way: “It is just wickedness from my co-cattle rearer. He attacked me while I was praying he escaped before my brothers came to my rescue. Though, it’s a destiny from God” said participant number 19.

Theme 6: Seeking social support

Seeking others’ help is another way for coping with the condition. A patient had this to say: “Actually I believe this injury is from God and I do ask people to recite the whole chapters of the holy Quran for me to get well. I also write some verses of the holy Quran on the slate, then wash and drink the water. Now I am looking for a way to raise the money for my rehabilitation” said participant number 1.

Theme 7: Positive re-framing

Staying positive about the condition and its outcomes is a way to cope with the condition. A participant aptly narrated this in the following manner: “I accepted that the injury is a destiny from God and that I cannot escape from the situation. As soon as I feel much better I would go back to my previous business or change a new one because I was once told by a friend that it is hardly for me to walk again” said participant number 3.

4. Discussion

The aim of the study was to find out the coping strategies used by patients with SCI in a Nigerian population. The study generated seven themes: religion, acceptance, denial, substance use, blame, seeking social support, and positive reframing. Although themes for coping strategies across different populations with different cultural backgrounds may be similar [23], the approaches to a particular theme could be different [13, 17-19]. For example, in Europe and America, people with SCI tend to use acceptance more than any other strategy [13, 18]. In contrast, in Iran, which is predominantly a Muslim country, religion is used as the main coping strategy. Similarly, in the present study, religion was used by 95% of the participants, which could be as a result of the fact that 90% of the participants were Muslims.

Even in Europe and America where acceptance was reported to be higher, a substantial percentage of people with SCI still use religion as a coping strategy [13, 18].This shows that individuals with SCI probably see connecting to their religious belief as an integral part of their wellbeing, which can help them to cope well with stressful situations or conditions [24]. Additionally, the use of religion as a coping strategy seems to be another way of accepting their conditions. In the present study, one of the participants stated: “Due to my old age, I consider this as part of life processes and it is God’s own making so am doing the possible I can to calm myself down so that at the end I would earn God’s reward.” Similarly, among Muslim populations, religion is seen as a springboard to deal with many different disease conditions such as epilepsy, depression and other psychiatric conditions and accept that it is the will of God [25-27]. Thus, Muslims may use religion as a way to accept their stressful condition.

In the present study, the least used coping strategies are positive reframing, denial, blame, substance use and seeking social support. The use of these strategies could also possibly be overshadowed by the religious beliefs. One of the creeds of Islam stipulates that Muslims accept destiny whether bad or good [28]. Thus, deeply entrenched religious belief can serve as catalyst for people to solely believe that it is the doing of God [17, 19, 25-27] and, therefore, accept their conditions without denial, blame or use of drugs or substance. According to Gaston-Johansson and colleagues, when people cope well with their conditions, it is less likely for them to resort to negative coping behaviors [10]. Additionally, the sole belief and dependence on the will of God may also undermine seeking social support. Seeking for social support can be because of instrumental support such as advice and assistance and emotional support such as sympathy [29].

Considering the foregoing, seeking for social support also pertains to seeking for assistance or advice and may also hide under the guise of religion. According to Babamohamadi and colleagues, some of their study participants asked people to help pray for them [17]. Similarly, in this study, some participants echoed the same sentiment as aptly mentioned by the following: participant: “Actually I believe this injury is from God and I do ask people to recite the whole chapters of the holy Quran for me to get well. I also write some verses of the holy Quran on the slate, then wash and drink the water. Now I am looking for away to raise the money for my rehabilitation.” said participant number 1. Similarly, in a Christian population, religious activities attendance was associated with the use of scripture to learn about the health or healing and frequency of prayer to get healing [30].

In every society, there are culturally endorsed coping strategies [30], and problems with societal acceptance and support were identified as barriers to the use of a particular coping strategy in Iran [19]. Consequently, none of the study participants reported use of distractions strategy, and this could be because of factors such as cultural interest in leisure activities such as watching films and reading habit, which seem to be less in the community where the study was carried out. Therefore, understanding patient coping strategies are important to help them navigate through the course of their condition. This is because people with SCI may be required to self-manage their condition due to the long-term nature of the condition. However, inability to cope such as with the use of positive reframing can often hinder self-management [31]. Self-management may aid in achieving greater functional independence and quality of life.

5. Conclusion

From the themes generated in the study, religion may be used as a way to accept a stressful condition. Therefore, healthcare professionals and caregivers are required to help reinforce positive coping strategies such as the use of religion and discourage or prevent the use of negative coping strategies such as substance use. The positive coping strategies can help the patients accept their conditions, work towards functional independence, and have a good quality of life. In contrast, the negative coping strategies can endanger patients’ life or predispose them to committing suicide and developing psychological and emotional problems. Additionally, there seems to be a thin line between many different coping strategies such as between religion and acceptance, as this may depend on the nature of one’s religious beliefs. Future studies should look at the possible interdependencies and relationships with demographic characteristics such as gender, age and ethnic background.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The Research Ethics Committees of Kano State Ministry of Health (for Murtala Muhammad Specialist Hospital) and National Orthopaedics Hospital, Dala, Kano, approved this study. All participants gave written informed consent before data collection began.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the patients who participated in the study and the staff at Murtala Muhammad Specialist Hospital and National Orthopaedics Hospital, Dala, Kano.

References

- Dijkers M. Quality of life after spinal cord injury: A meta-analysis of the effects of disablement components. Spinal Cord. 1997; 35:829-40 [DOI:10.1038/sj.sc.3100571] [PMID]

- Westgren N, Richard Levi. Quality of life and traumatic spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1998; 79(11):1433–9. [DOI:10.1016/S0003-9993(98)90240-4]

- Jackson AB, Dijkers M, Devivo MJ, Poczatek RB. A demographic profile of new traumatic spinal cord injury–changes and stablity over 30 years. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2004; 85: 1740–8. [DOI:10.1016/j.apmr.2004.04.035] [PMID]

- Gill M. Psychosocial implications of spinal cord injury. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly. 1999; 22(2):1-7. [PMID]

- Lidal IB, Huynh TK, Biering-Sørensen F. Return to work following spinal cord injury: A review. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2007; 29(17):1341-75. [DOI:10.1080/09638280701320839] [PMID]

- Song HY, Nam KA. Coping strategies, physical function, and social adjustment in people with spinal cord injury. Rehabilitation Nursing Journal. 2010; 35:8–15. [DOI:10.1002/j.2048-7940.2010.tb00025.x]

- Kennedy P, Garmon-Jones L. Self-harm and suicide before and after spinal cord injury: A systematic review. Spinal Cord 2017; 55:2-7. [DOI:10.1038/sc.2016.135]

- Wyndaele JJ. Life and quality of life after Spinal Cord Injury. Spinal Cord. 2017; 55:1. [DOI:10.1038/sc.2016.185]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Dunkel-Schetter C, Delongis A, Gruen R. Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986; 50:992–1003. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.50.5.992] [PMID]

- Gaston-Johansson F, Haisfield-Wolfe ME, Reddick B, Goldstein N, Lawal TA. The relationships among coping strategies, religious coping, and spirituality in African American women with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2013; 40(2):120-31. [DOI:10.1188/13.ONF.120-131] [PMID]

- Song HY. Modeling social reintegration in persons with spinal cord injury. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2005; 27(3):131-41. [DOI:10.1080/09638280400007372]

- Pollard C, Kennedy P. A longitudinal analysis of emotional impact, coping strategies and post-traumatic psychological growth following spinal cord injury: A 10-year review. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2007; 12(3):347-62. [DOI:10.1348/135910707X197046] [PMID]

- Elfstrom ML, Kennedy P, Lude P, Taylor N. Condition-related coping strategies in persons with spinal cord lesion: A cross-national validation of the Spinal Cord Lesion-related Coping Strategies Questionnaire in four community samples. Spinal Cord. 2007; 45:420–8. [DOI:10.1038/sj.sc.3102003] [PMID]

- Allen AB, Leary MR. Self-compassion, stress, and coping. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2010; 4(2):107–18. [DOI:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00246.x] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Lazarus RS, DeLongis A, Folkman S, Gruen R. Stress and adaptational outcomes: The problem of confounded measures. American Psychologist. 1985; 40:770–779. [DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.40.7.770] [PMID]

- Skinner EA, Edge K, Altman J, Sherwood H. Searching for the structure of coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin. 2003; 129:216–69. [DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.216] [PMID]

- Babamohamadi H, Negarandeh R Dehghan-Nayeri N. Coping strategies used by people with spinal cord injury: A qualitative study. Spinal Cord. 2011; 49:832–7 [DOI:10.1038/sc.2011.10] [PMID]

- Anderson CJ, Vogel LC, Chlan KM, Betz RR. Coping with spinal cord injury: Strategies used by adults who sustained their injuries as children or adolescents. The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine. 2008; 31:290–6. [DOI:10.1080/10790268.2008.11760725] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Babamohamadi H, Negarandeh R, Dehghan-Nayeri N. Barriers to and facilitators of coping with spinal cord injury for Iranian patients: A qualitative study. Nursing & Health Sciences. 2011; 13(2):207-15. [DOI:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00602.x] [PMID]

- Fusch PI, Ness LR. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qualitative Report. 2015; 20(9):1408-16.

- Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ. The mini-mental state examination: A comprehensive review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1992; 40(9):922-35. [DOI:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01992.x]

- Mungas D. In-office mental status testing: A practical guide. Geriatrics. 1991; 46(7):54-8. [PMID]

- Conner KO, Copeland VC, Grote NK, Rosen D, Albert S, McMurray ML, et al. Barriers to treatment and culturally endorsed coping strategies among depressed African-American older adults. Aging and Mental Health. 2010; 14(8):971–83. [DOI:10.1080/13607863.2010.501061] [PMID] [PMCID]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT jr. Personality, coping and coping effectiveness in adult sample. Journal of Personality. 1986; 54:385-405. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1986.tb00401.x]

- Meer S, Mir G. Muslims and depression: The role of religious beliefs in therapy. Journal of Integrative Psychology and Therapeutics. 2014. [DOI:10.7243/2054-4723-2-2]

- Sabry WM, Vohra A. Role of Islam in the management of Psychiatric disorders. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 2013; 55(Suppl 2):S205–S214. [DOI:10.4103/0019-5545.105534]

- Ismail H, Wright J, Rhodes P, Small N. Religious beliefs about causes and treatment of epilepsy. British Journal of General Practice. 2005; 55(510):26–31. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Ferid I. Why belief in destiny one of the pillars of Islamic Creed? [Internet]. 2013 [Updated 2013 May 17]. Available from: http://www.thepenmagazine.net/why-belief-in-destiny-one-of-the-pillars-of-islamic-creed/

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: theoretically based approach.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989; 56(2):267–83. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267]

- Cornell NR. Factors Influencing the Likelihood of Using Religion as a Coping Mechanism in Response to Life Event Stressors. [Honors Theses]. Minnesota: College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University; 2015.

- Munce SEP, Webster F, Fehlings MG, Straus SE, Jang E, Jagla SB. Perceived facilitators and barriers to self-management in individuals with traumatic spinal cord injury: A qualitative descriptive study. BMC. 2014; 14:48. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2377-14-48] [PMID] [PMCID]

Article type: Original Research Articles |

Subject:

Neurorehabilitation

Received: 2017/12/24 | Accepted: 2017/06/7 | Published: 2018/06/1

Received: 2017/12/24 | Accepted: 2017/06/7 | Published: 2018/06/1

References

1. Dijkers M. Quality of life after spinal cord injury: A meta-analysis of the effects of disablement components. Spinal Cord. 1997; 35:829-40 [DOI:10.1038/sj.sc.3100571] [PMID] [DOI:10.1038/sj.sc.3100571]

2. Westgren N, Richard Levi. Quality of life and traumatic spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1998; 79(11):1433–9. [DOI:10.1016/S0003-9993(98)90240-4] [DOI:10.1016/S0003-9993(98)90240-4]

3. Jackson AB, Dijkers M, Devivo MJ, Poczatek RB. A demographic profile of new traumatic spinal cord injury–changes and stablity over 30 years. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2004; 85: 1740–8. [DOI:10.1016/j.apmr.2004.04.035] [PMID] [DOI:10.1016/j.apmr.2004.04.035]

4. Gill M. Psychosocial implications of spinal cord injury. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly. 1999; 22(2):1-7. [PMID] [DOI:10.1097/00002727-199908000-00002] [PMID]

5. Lidal IB, Huynh TK, Biering-Sørensen F. Return to work following spinal cord injury: A review. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2007; 29(17):1341-75. [DOI:10.1080/09638280701320839] [PMID] [DOI:10.1080/09638280701320839]

6. Song HY, Nam KA. Coping strategies, physical function, and social adjustment in people with spinal cord injury. Rehabilitation Nursing Journal. 2010; 35:8–15. [DOI:10.1002/j.2048-7940.2010.tb00025.x] [DOI:10.1002/j.2048-7940.2010.tb00025.x]

7. Kennedy P, Garmon-Jones L. Self-harm and suicide before and after spinal cord injury: A systematic review. Spinal Cord 2017; 55:2-7. [DOI:10.1038/sc.2016.135] [DOI:10.1038/sc.2016.135]

8. Wyndaele JJ. Life and quality of life after Spinal Cord Injury. Spinal Cord. 2017; 55:1. [DOI:10.1038/sc.2016.185] [DOI:10.1038/sc.2016.185]

9. Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Dunkel-Schetter C, Delongis A, Gruen R. Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986; 50:992–1003. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.50.5.992] [PMID] [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.50.5.992]

10. Gaston-Johansson F, Haisfield-Wolfe ME, Reddick B, Goldstein N, Lawal TA. The relationships among coping strategies, religious coping, and spirituality in African American women with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2013; 40(2):120-31. [DOI:10.1188/13.ONF.120-131] [PMID] [DOI:10.1188/13.ONF.120-131]

11. Song HY. Modeling social reintegration in persons with spinal cord injury. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2005; 27(3):131-41. [DOI:10.1080/09638280400007372] [DOI:10.1080/09638280400007372]

12. Pollard C, Kennedy P. A longitudinal analysis of emotional impact, coping strategies and post-traumatic psychological growth following spinal cord injury: A 10-year review. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2007; 12(3):347-62. [DOI:10.1348/135910707X197046] [PMID] [DOI:10.1348/135910707X197046]

13. Elfstrom ML, Kennedy P, Lude P, Taylor N. Condition-related coping strategies in persons with spinal cord lesion: A cross-national validation of the Spinal Cord Lesion-related Coping Strategies Questionnaire in four community samples. Spinal Cord. 2007; 45:420–8. [DOI:10.1038/sj.sc.3102003] [PMID] [DOI:10.1038/sj.sc.3102003]

14. Allen AB, Leary MR. Self-compassion, stress, and coping. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2010; 4(2):107–18. [DOI:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00246.x] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00246.x]

15. Lazarus RS, DeLongis A, Folkman S, Gruen R. Stress and adaptational outcomes: The problem of confounded measures. American Psychologist. 1985; 40:770–779. [DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.40.7.770] [PMID] [DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.40.7.770]

16. Skinner EA, Edge K, Altman J, Sherwood H. Searching for the structure of coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin. 2003; 129:216–69. [DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.216] [PMID] [DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.216]

17. Babamohamadi H, Negarandeh R Dehghan-Nayeri N. Coping strategies used by people with spinal cord injury: A qualitative study. Spinal Cord. 2011; 49:832–7 [DOI:10.1038/sc.2011.10] [PMID] [DOI:10.1038/sc.2011.10]

18. Anderson CJ, Vogel LC, Chlan KM, Betz RR. Coping with spinal cord injury: Strategies used by adults who sustained their injuries as children or adolescents. The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine. 2008; 31:290–6. [DOI:10.1080/10790268.2008.11760725] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1080/10790268.2008.11760725]

19. Babamohamadi H, Negarandeh R, Dehghan-Nayeri N. Barriers to and facilitators of coping with spinal cord injury for Iranian patients: A qualitative study. Nursing & Health Sciences. 2011; 13(2):207-15. [DOI:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00602.x] [PMID] [DOI:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00602.x]

20. Fusch PI, Ness LR. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qualitative Report. 2015; 20(9):1408-16.

21. Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ. The mini-mental state examination: A comprehensive review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1992; 40(9):922-35. [DOI:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01992.x] [DOI:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01992.x]

22. Mungas D. In-office mental status testing: A practical guide. Geriatrics. 1991; 46(7):54-8. [PMID] [PMID]

23. Conner KO, Copeland VC, Grote NK, Rosen D, Albert S, McMurray ML, et al. Barriers to treatment and culturally endorsed coping strategies among depressed African-American older adults. Aging and Mental Health. 2010; 14(8):971–83. [DOI:10.1080/13607863.2010.501061] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1080/13607863.2010.501061]

24. McCrae RR, Costa PT jr. Personality, coping and coping effectiveness in adult sample. Journal of Personality. 1986; 54:385-405. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1986.tb00401.x] [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1986.tb00401.x]

25. Meer S, Mir G. Muslims and depression: The role of religious beliefs in therapy. Journal of Integrative Psychology and Therapeutics. 2014. [DOI:10.7243/2054-4723-2-2] [DOI:10.7243/2054-4723-2-2]

26. Sabry WM, Vohra A. Role of Islam in the management of Psychiatric disorders. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 2013; 55(Suppl 2):S205–S214. [DOI:10.4103/0019-5545.105534] [DOI:10.4103/0019-5545.105534]

27. Ismail H, Wright J, Rhodes P, Small N. Religious beliefs about causes and treatment of epilepsy. British Journal of General Practice. 2005; 55(510):26–31. [PMID] [PMCID] [PMID] [PMCID]

28. Ferid I. Why belief in destiny one of the pillars of Islamic Creed? [Internet]. 2013 [Updated 2013 May 17]. Available from: http://www.thepenmagazine.net/why-belief-in-destiny-one-of-the-pillars-of-islamic-creed/

29. Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: theoretically based approach.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989; 56(2):267–83. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267] [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267]

30. Cornell NR. Factors Influencing the Likelihood of Using Religion as a Coping Mechanism in Response to Life Event Stressors. [Honors Theses]. Minnesota: College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University; 2015.

31. Munce SEP, Webster F, Fehlings MG, Straus SE, Jang E, Jagla SB. Perceived facilitators and barriers to self-management in individuals with traumatic spinal cord injury: A qualitative descriptive study. BMC. 2014; 14:48. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2377-14-48] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI:10.1186/1471-2377-14-48]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |