Volume 17, Issue 2 (June 2019)

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2019, 17(2): 129-140 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Zanjari N, Sharifian Sani M, Hosseini-Chavoshi M, Rafiey H, Mohammadi-Shahboulaghi F. Development and Validation of Successful Aging Instrument. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2019; 17 (2) :129-140

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-912-en.html

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-912-en.html

Nasibeh Zanjari *1

, Maryam Sharifian Sani2

, Maryam Sharifian Sani2

, Meimanat Hosseini-Chavoshi3

, Meimanat Hosseini-Chavoshi3

, Hassan Rafiey2

, Hassan Rafiey2

, Farahnaz Mohammadi-Shahboulaghi4

, Farahnaz Mohammadi-Shahboulaghi4

, Maryam Sharifian Sani2

, Maryam Sharifian Sani2

, Meimanat Hosseini-Chavoshi3

, Meimanat Hosseini-Chavoshi3

, Hassan Rafiey2

, Hassan Rafiey2

, Farahnaz Mohammadi-Shahboulaghi4

, Farahnaz Mohammadi-Shahboulaghi4

1- Iranian Research Centre on Aging, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Social Work, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia.

4- Department of Nursing, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Social Work, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia.

4- Department of Nursing, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 1437 kb]

(4064 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (5380 Views)

Full-Text: (2043 Views)

Highlights

● The self-perceived successful aging instrument with a seven-factor structure has appropriate content and construct validity as well as good reliability.

● This successful aging instrument covers all the individual (e.g. bio-psychological health), interpersonal (social support), and social (financial and environmental security) needs to better experience aging.

Plain Language Summary

Planning for aging well is one of the main challenges of social policymakers. In this regard, we need to evaluate the status quo of older adults in society and assess how people age and adopt with the losses of the aging process. In other words, how people age successfully is a crucial issue in social policy. In this article, the researchers develop an instrument for measuring successful aging concept based on the viewpoints of older adults. The successful aging instrument has seven dimensions, with 54 items. This instrument does not divide the elderly into groups of successful and unsuccessful but considers successful aging as a continuum. The successful aging instrument covers all the individual (e.g. bio-psychological health), interpersonal (social support), and social (financial and environmental security) needs to achieve better aging. Among these seven dimensions of successful aging, the most influential factor is “psychological well-being” which comprised “positive characteristics and capabilities of elderly people”, “satisfaction with life”, and “positive aging perceptions”. In summary, policymakers should consider the multidimensional and contextual nature of successful aging.

1. Introduction

The transition from midlife to later life is often accompanied by other transitions such as retirement, empty nest syndrome, and widowhood. While some older adults well adapt to the changes of aging and experience it well, some do not; they suffer from bio-psycho-social problems. To assess how people can age well and to identify the involved processes and components, researchers have searched for the concept of Successful Aging (SA) [1].

SA is a multidimensional and interdisciplinary concept. Despite the great body of research on SA, there is no consensus on its meaning or measuring [2-4]. This concept emerged from Robert Havighurst [5]. He focused on life satisfaction as a definition of successful aging. The SA developed by Rowe and Kahn consisted of three main practical dimensions, including disease avoidance, high physical and cognitive function maintenance, and an active engagement with life [6]. This definition of SA was modified by Crowther, Parker, Achenbaum, Larimore and Koenig. They revised the model and added the spirituality factor [7].

In the second version of successful aging, Rowe and Kahn expanded the concept and cited aging in society and the role of human capital life-course perspective as parts of successful aging [8]. Another well-known model of SA that explains adapting to aging is Selection, Optimization, and Compensation (SOC) model by Baltes and Baltes [9]. Then, Schultz and Heckhausen (1996) developed a life span model based on the SOC and highlighted life course development [10]. Moreover, studies with qualitative and subjective approaches suggested SA as a contextual and cultural concept with a culturally oriented framework [11]. Thus, SA is used in different alternative terms, including gerotranscendence [12] and harmonious aging [13].

Regarding the objective dimension of successful aging, studies have used validated mental and physical tests such as MMSE and ADL [3]. Moreover, in terms of the subjective aspect of SA, researchers have directly asked elderly people about their aging process [14]. In most investigations, the elderly are divided into two groups of successful and unsuccessful. However, in reality, we need to consider SA as a continuum [15].

In addition, there have been attempts to develop a distinguished subjective SA instrument that determines life satisfaction [16], life management [17], and attitude toward SA [18]. Furthermore, SA assessment instrument by Troutman, Nies, Small and Bates is developed based on a literature review [19]. Therefore, the present study aimed to develop a multidimensional SA instrument based on elderly people’s perceptions and literature review.

2. Methods

In this Study we used a mixed method approach (quantitative and qualitative data) to develop and validate the SA assessment tool. The study included 5 sequential phases that originated from the conceptualization of SA and its dimensions. Subsequently, an item pool was designed and content validity and face validity were evaluated. A revised instrument was applied on a larger population of older adults in Tehran City, Iran, through a survey to measure construct validity and convergent validity with the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) [20] and the known-groups validity of instrument. Finally, the reliability of the instrument was estimated by time stability and internal consistency.

The required data were gathered in 2015 through qualitative and quantitative approaches. In the qualitative phase, we interviewed 64 participants aged ≥60 years who lived in Tehran. We used purposeful stratified sampling to capture maximum variation [21]. The number of male and female participants was equal with the Mean±SD age of 72±9.07 years. The qualitative interview key questions included “the meaning of SA”, “the characteristic of a successful elderly person”, and “adapting to aging losses”.

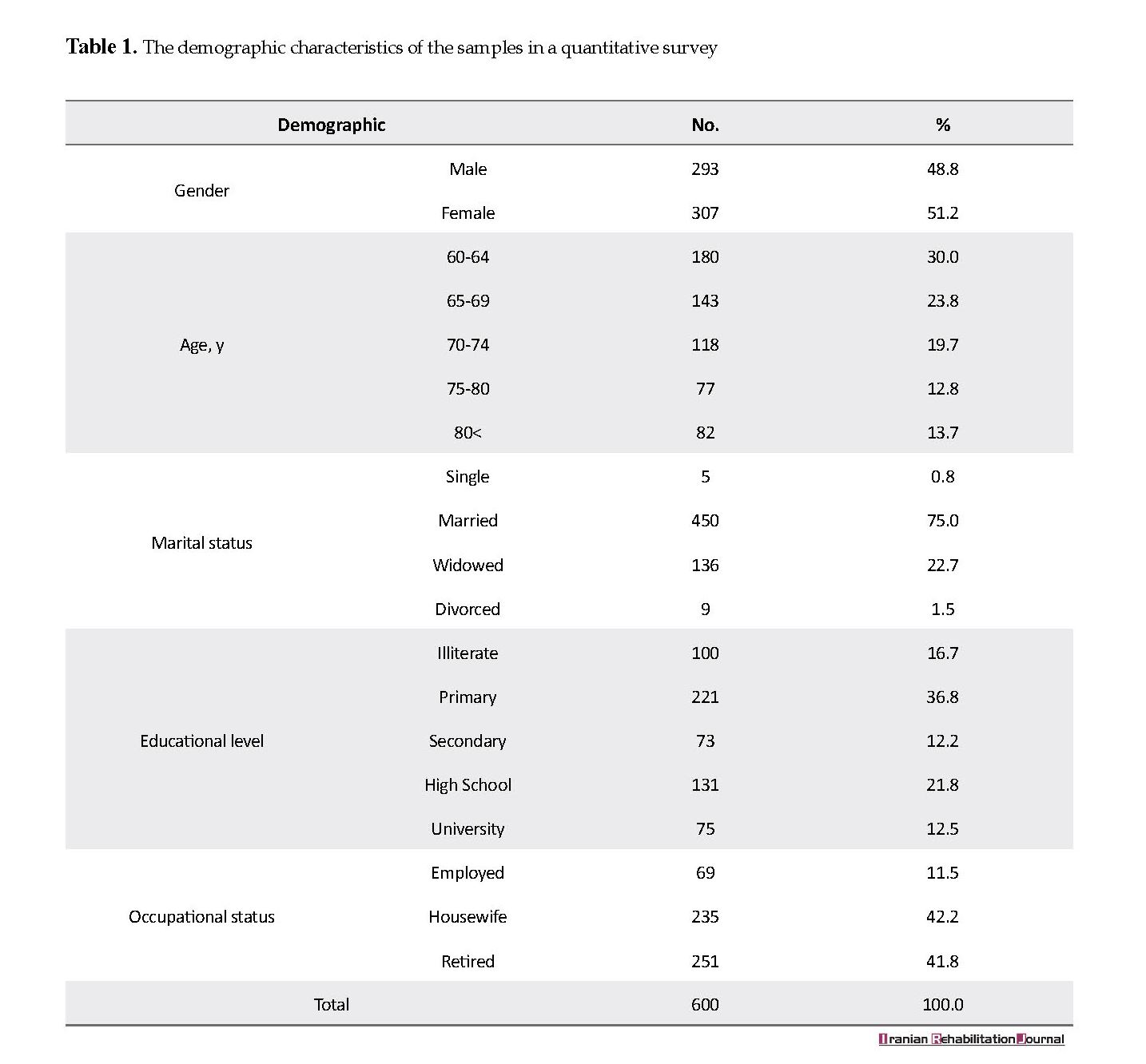

In the quantitative phase, using stratified multistage sampling, we interviewed 600 older adults in 22 districts of Tehran. The female to male ratio was slightly higher in the quantitative samples. Their mean age was approximately 70 years. About 75% of the samples were married and 23% were widowed. Approximately 17% of the samples were illiterate, 37% had primary education, and only 12% had a university degree. Regarding activity, the obtained data suggested that 42% of the samples were retired, and 12% were still in the labor force (Table 1).

3. Results

Conceptualization

We conceptualized SA with a directed content analysis approach. We explored SA dimensions through an integrative review and qualitative study of 64 older adults on their perceptions of SA [22, 23]. Qualitative data analysis indicated 16 sub-categories of SA. Additionally, Figure 1 shows 6 six main categories, as follows: “social well-being”, “psychological well-being”, “physical health”, “spirituality and transcendence”, “financial security”, and “elderly-friendly social context and environment”.

● The self-perceived successful aging instrument with a seven-factor structure has appropriate content and construct validity as well as good reliability.

● This successful aging instrument covers all the individual (e.g. bio-psychological health), interpersonal (social support), and social (financial and environmental security) needs to better experience aging.

Plain Language Summary

Planning for aging well is one of the main challenges of social policymakers. In this regard, we need to evaluate the status quo of older adults in society and assess how people age and adopt with the losses of the aging process. In other words, how people age successfully is a crucial issue in social policy. In this article, the researchers develop an instrument for measuring successful aging concept based on the viewpoints of older adults. The successful aging instrument has seven dimensions, with 54 items. This instrument does not divide the elderly into groups of successful and unsuccessful but considers successful aging as a continuum. The successful aging instrument covers all the individual (e.g. bio-psychological health), interpersonal (social support), and social (financial and environmental security) needs to achieve better aging. Among these seven dimensions of successful aging, the most influential factor is “psychological well-being” which comprised “positive characteristics and capabilities of elderly people”, “satisfaction with life”, and “positive aging perceptions”. In summary, policymakers should consider the multidimensional and contextual nature of successful aging.

1. Introduction

The transition from midlife to later life is often accompanied by other transitions such as retirement, empty nest syndrome, and widowhood. While some older adults well adapt to the changes of aging and experience it well, some do not; they suffer from bio-psycho-social problems. To assess how people can age well and to identify the involved processes and components, researchers have searched for the concept of Successful Aging (SA) [1].

SA is a multidimensional and interdisciplinary concept. Despite the great body of research on SA, there is no consensus on its meaning or measuring [2-4]. This concept emerged from Robert Havighurst [5]. He focused on life satisfaction as a definition of successful aging. The SA developed by Rowe and Kahn consisted of three main practical dimensions, including disease avoidance, high physical and cognitive function maintenance, and an active engagement with life [6]. This definition of SA was modified by Crowther, Parker, Achenbaum, Larimore and Koenig. They revised the model and added the spirituality factor [7].

In the second version of successful aging, Rowe and Kahn expanded the concept and cited aging in society and the role of human capital life-course perspective as parts of successful aging [8]. Another well-known model of SA that explains adapting to aging is Selection, Optimization, and Compensation (SOC) model by Baltes and Baltes [9]. Then, Schultz and Heckhausen (1996) developed a life span model based on the SOC and highlighted life course development [10]. Moreover, studies with qualitative and subjective approaches suggested SA as a contextual and cultural concept with a culturally oriented framework [11]. Thus, SA is used in different alternative terms, including gerotranscendence [12] and harmonious aging [13].

Regarding the objective dimension of successful aging, studies have used validated mental and physical tests such as MMSE and ADL [3]. Moreover, in terms of the subjective aspect of SA, researchers have directly asked elderly people about their aging process [14]. In most investigations, the elderly are divided into two groups of successful and unsuccessful. However, in reality, we need to consider SA as a continuum [15].

In addition, there have been attempts to develop a distinguished subjective SA instrument that determines life satisfaction [16], life management [17], and attitude toward SA [18]. Furthermore, SA assessment instrument by Troutman, Nies, Small and Bates is developed based on a literature review [19]. Therefore, the present study aimed to develop a multidimensional SA instrument based on elderly people’s perceptions and literature review.

2. Methods

In this Study we used a mixed method approach (quantitative and qualitative data) to develop and validate the SA assessment tool. The study included 5 sequential phases that originated from the conceptualization of SA and its dimensions. Subsequently, an item pool was designed and content validity and face validity were evaluated. A revised instrument was applied on a larger population of older adults in Tehran City, Iran, through a survey to measure construct validity and convergent validity with the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) [20] and the known-groups validity of instrument. Finally, the reliability of the instrument was estimated by time stability and internal consistency.

The required data were gathered in 2015 through qualitative and quantitative approaches. In the qualitative phase, we interviewed 64 participants aged ≥60 years who lived in Tehran. We used purposeful stratified sampling to capture maximum variation [21]. The number of male and female participants was equal with the Mean±SD age of 72±9.07 years. The qualitative interview key questions included “the meaning of SA”, “the characteristic of a successful elderly person”, and “adapting to aging losses”.

In the quantitative phase, using stratified multistage sampling, we interviewed 600 older adults in 22 districts of Tehran. The female to male ratio was slightly higher in the quantitative samples. Their mean age was approximately 70 years. About 75% of the samples were married and 23% were widowed. Approximately 17% of the samples were illiterate, 37% had primary education, and only 12% had a university degree. Regarding activity, the obtained data suggested that 42% of the samples were retired, and 12% were still in the labor force (Table 1).

3. Results

Conceptualization

We conceptualized SA with a directed content analysis approach. We explored SA dimensions through an integrative review and qualitative study of 64 older adults on their perceptions of SA [22, 23]. Qualitative data analysis indicated 16 sub-categories of SA. Additionally, Figure 1 shows 6 six main categories, as follows: “social well-being”, “psychological well-being”, “physical health”, “spirituality and transcendence”, “financial security”, and “elderly-friendly social context and environment”.

Developing the item pool and content validity

With respect to the findings from the qualitative phase, we designed an initial item pool that included 187 items. It’s content and face validities were evaluated by 12 gerontology and psychometric experts. They rated the relevancy of items to SA concept on a scale of 0-10. Based on the expert panel’s evaluation, the initial instrument was revised (rephrasing some items) and reduced to 85 items. Moreover, the revised initial instrument was completed by 64 elderly who participated in the qualitative study; based on the achieved results, 4 items were deleted due to lack of clarity.

With respect to the findings from the qualitative phase, we designed an initial item pool that included 187 items. It’s content and face validities were evaluated by 12 gerontology and psychometric experts. They rated the relevancy of items to SA concept on a scale of 0-10. Based on the expert panel’s evaluation, the initial instrument was revised (rephrasing some items) and reduced to 85 items. Moreover, the revised initial instrument was completed by 64 elderly who participated in the qualitative study; based on the achieved results, 4 items were deleted due to lack of clarity.

For evaluating bias between the developed instrument and elderly peoples’ perceptions, we conducted a crossover analysis [24, 25]; we quantized (0, 1) the sub-categories of the qualitative data for every participant by the Interrespondent Matrix (Table 2). Then, we tested the correlation between this set of data and the scores of older adults obtained by the initial instrument of assessing SA. The obtained results revealed a significant and high canonical correlation between the quantitative and qualitative data. The Wilk’s Lambda test results were significant at P<0.05.

Construct validity

The revised instrument was prepared for field test. The instrument included 81 items with a Likert-type scale, scored from 0 to 4. Higher scores indicated more frequent/stronger positive responses. Moreover, we included 12 negative sentences that we converted their score for analysis. After conducting a survey and gathering data from 600 older adults, we determined its construct validity by Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA).

The screen plot suggested 7 factors, due to the way the slope leveled off. Evaluating construct validity was performed through EFA with Promax rotation, as well as factor matrix (loading) cut-off points as high as 0.4; it yielded 7 factors, and finally 54 items remained (Table 3). The percentage of variance explained by the total items was equal to 51%.

The 7 dimensions of SA extracted from factor analysis were labeled as follows: 1: Psychological well-being (15 items); 2: Social support (10 items); 3: Financial and environmental security (9 items); 4: Spirituality (4 items); 5: Physical and mental health (7 items);6: Functional health (5 items); 7: and health-related behaviors (4 items).

Construct validity

The revised instrument was prepared for field test. The instrument included 81 items with a Likert-type scale, scored from 0 to 4. Higher scores indicated more frequent/stronger positive responses. Moreover, we included 12 negative sentences that we converted their score for analysis. After conducting a survey and gathering data from 600 older adults, we determined its construct validity by Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA).

The screen plot suggested 7 factors, due to the way the slope leveled off. Evaluating construct validity was performed through EFA with Promax rotation, as well as factor matrix (loading) cut-off points as high as 0.4; it yielded 7 factors, and finally 54 items remained (Table 3). The percentage of variance explained by the total items was equal to 51%.

The 7 dimensions of SA extracted from factor analysis were labeled as follows: 1: Psychological well-being (15 items); 2: Social support (10 items); 3: Financial and environmental security (9 items); 4: Spirituality (4 items); 5: Physical and mental health (7 items);6: Functional health (5 items); 7: and health-related behaviors (4 items).

Convergent validity

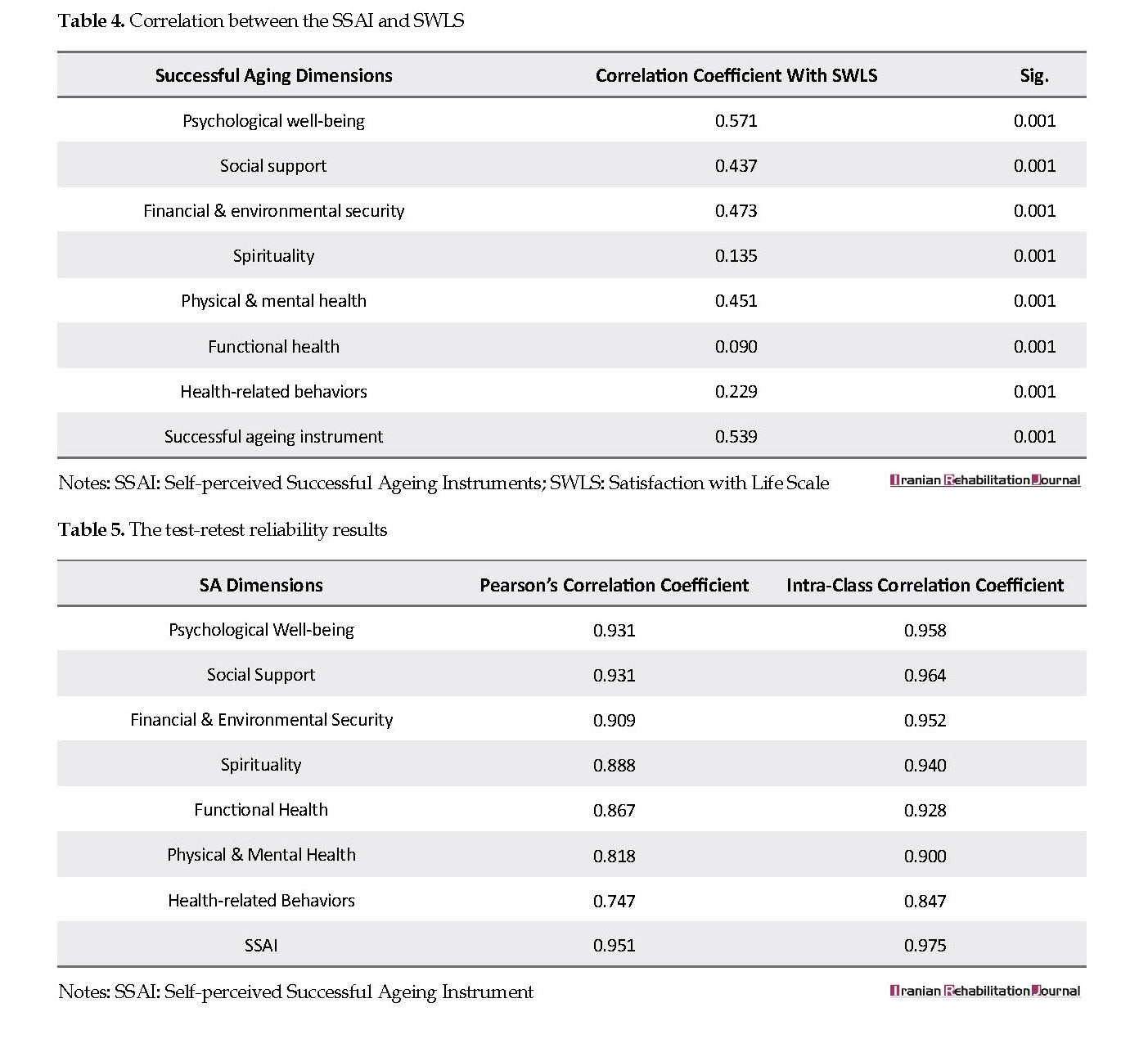

In addition to the structural (construct) validity, we assessed the convergent validity of the Self-perceived Successful Ageing Instruments (SSAI), compared with the SWLS [20]. Life satisfaction has been identified as an indicator of SA [5, 16, 26]. Satisfaction with life has been the most commonly proposed definition of SA and the most commonly investigated concept [27]. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated to examine the relationships between the scores of the two instruments. A low correlation coefficient (except for psychological well-being) suggested that the SSAI is a different instrument (Table 4).

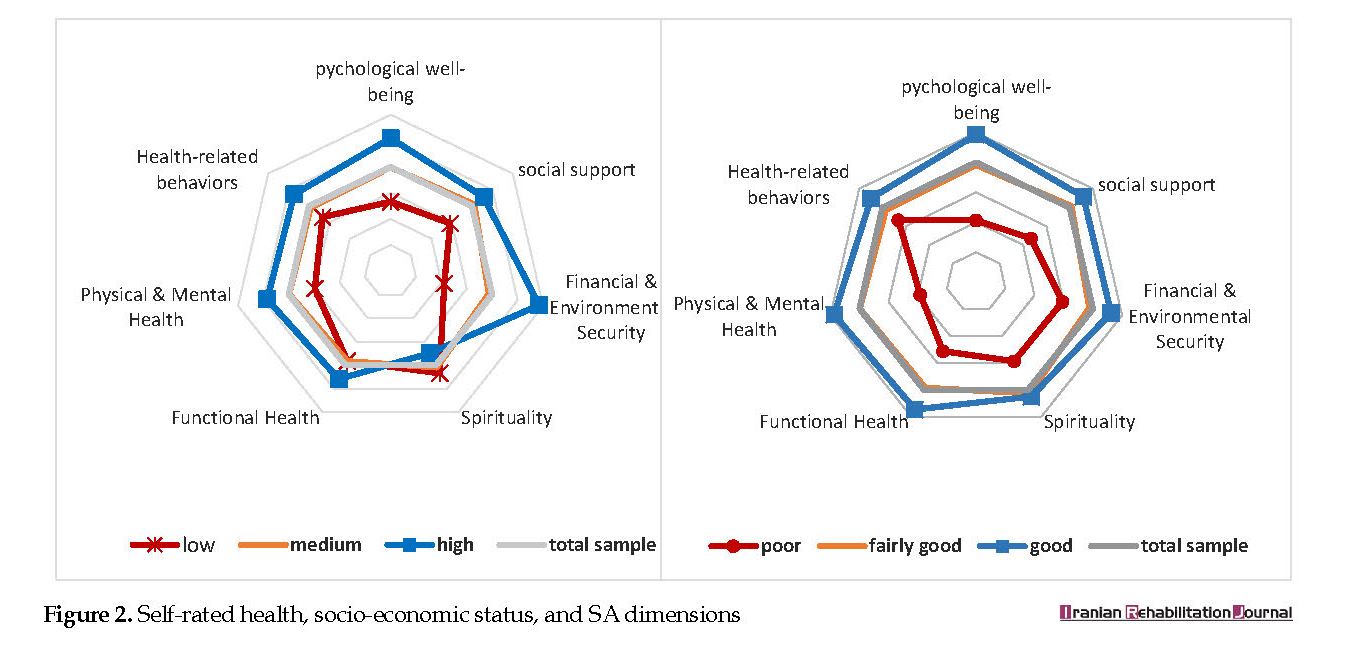

Known-groups validity

The known-groups validity revealed that SA was sensitive to differences and similarities in various groups; e.g. different social classes and different health status. People with low socio-economic and poor health status obtained lower scores of SA. Conversely, older adults reporting good self-rated health with higher socioeconomic status achieved higher scores of SA (Figure 2).

Reliability

Internal consistency

The internal consistency of the overall SSAI was equal to 0.93. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of most subscales ranged from 0.7 to 0.9. Thus, the SSAI has a high internal consistency (Figure 3).

In addition to the structural (construct) validity, we assessed the convergent validity of the Self-perceived Successful Ageing Instruments (SSAI), compared with the SWLS [20]. Life satisfaction has been identified as an indicator of SA [5, 16, 26]. Satisfaction with life has been the most commonly proposed definition of SA and the most commonly investigated concept [27]. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated to examine the relationships between the scores of the two instruments. A low correlation coefficient (except for psychological well-being) suggested that the SSAI is a different instrument (Table 4).

Known-groups validity

The known-groups validity revealed that SA was sensitive to differences and similarities in various groups; e.g. different social classes and different health status. People with low socio-economic and poor health status obtained lower scores of SA. Conversely, older adults reporting good self-rated health with higher socioeconomic status achieved higher scores of SA (Figure 2).

Reliability

Internal consistency

The internal consistency of the overall SSAI was equal to 0.93. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of most subscales ranged from 0.7 to 0.9. Thus, the SSAI has a high internal consistency (Figure 3).

Test-retest reliability (Time consistency)

We examined the test-retest reliability (a 2-weeks interval) of the tool on 40 older adults to determine the time consistency. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (0.951) and ICC (0.975) indicated high stability of the instrument over a short time period (Table 5).

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to develop and evaluate a multidimensional self-perceived instrument to measure SA. Measuring SA based on clinical outcomes or physical and cognitive decline could not capture the complete aging experience of older people or lay opinions about aging well [15]. Thus, we constructed a SA instrument based on the viewpoint of elderly people, named SSAI. The crucial difference between SSAI and previous instruments like SAI [19] arises from our conceptualization of SA based on the lay perspective and literature review. The SSAI assesses the SA at an individual level. However, it is not limited to the bio-psychological health, and considers interpersonal and environmental levels of SA, as well. The obtained qualitative data were in line with the previous studies [28, 29] recognizing SA as a multidimensional concept. The EFA reduced the items to 54 items and loaded them into 7 factors/dimensions.

We examined the test-retest reliability (a 2-weeks interval) of the tool on 40 older adults to determine the time consistency. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (0.951) and ICC (0.975) indicated high stability of the instrument over a short time period (Table 5).

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to develop and evaluate a multidimensional self-perceived instrument to measure SA. Measuring SA based on clinical outcomes or physical and cognitive decline could not capture the complete aging experience of older people or lay opinions about aging well [15]. Thus, we constructed a SA instrument based on the viewpoint of elderly people, named SSAI. The crucial difference between SSAI and previous instruments like SAI [19] arises from our conceptualization of SA based on the lay perspective and literature review. The SSAI assesses the SA at an individual level. However, it is not limited to the bio-psychological health, and considers interpersonal and environmental levels of SA, as well. The obtained qualitative data were in line with the previous studies [28, 29] recognizing SA as a multidimensional concept. The EFA reduced the items to 54 items and loaded them into 7 factors/dimensions.

We found some differences between the preliminary six-category conceptual framework that was based on qualitative phases and the current 7 categories identified based on EFA. “Psychological well-being” as the strongest factor which explained the greatest percentage of variance in the SA based on EFA, comprised “positive characteristics and capabilities of elderly people”, “satisfaction with life”, and “positive aging perceptions”. In the second factor, the “social support” was the only sub-category remaining from the “social well-being” category. Moreover, the items of “financial security” and “elderly-friendly environment and social context” categories were combined in one factor.

The extracted 7 factors in our study are documented in the literature as the key dimensions of SA. Cho et al. indicated subjective well-being among oldest old as a dimension of SA [30]. Jopp et al. developed the meaning of SA in sight of the elderly from the United States and Germany in terms of the resources, behaviors, and psychological factors [28]. Martin et al., Martinson et al., and Cosco et al. indicated the bio-psycho-social and environmental aspects of SA concept [29, 31, 32]. Moreover, the previous studies on aging in Iran revealed the importance of psychological well-being and social support dimensions in health and aging well [33, 34].

The convergent validity of the instrument suggested a significant correlation between life satisfaction and the SSAI. This is consistent with a study on the SAI instrument [18]. Regarding the importance of social classes and health status in the scoring of SA [2, 30-32], we tested the known-groups validity. The obtained results indicated lower scores for the elderly with poor health and low socioeconomic status, and vice versa. Thus, the instrument can discriminate social groups. In addition, the SSAI had a high internal reliability (0.93). Moreover, assessing test-retest reliability revealed a significant and high Intra-class correlation coefficient (0.975). Thus, the validity and reliability of SSAI were supported by the data, including content validity, construct validity, known-groups validity, convergent validity, test-retest reliability, and internal consistency.

This study had some limitations. The SSAI was developed using a sample of Iranian elderlies and cultural constructs. Therefore, this instrument needs to be validated in other contexts. In addition, the conceptual framework emerged from an urban context and elderly people living in rural areas were excluded from this research. It is recommended that the SSAI psychometric characteristics be evaluated in different cultural contexts.

5. Conclusion

This study indicated that the SSAI has appropriate content and construct validity. Moreover, the obtained results suggested measuring SA concepts and developing social policies in this area considering all 7 dimensions of SA to cover all the individual (e.g. bio-psychological health), interpersonal (social support), and social (financial and environmental security) needs. In conclusion, the present study supports the validity and reliability of a multidimensional self-perceived instrument for assessing SA. It also provides evidence in the support of the utility of a new instrument to measure SA.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The development of successful ageing instrument was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Funding

This article has been extracted from The PhD. thesis of first author, in Iranian Research Centre on Aging, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and methodology: Nasibeh Zanjari; Supervision: Maryam Sharifian Sani, Meimanat Hosseini Chavoshi; Investigation and draft preparation: Nasibeh Zanjari; and Review and editing: Hassan Rafiey, Farahnaz Mohammadi-Shahbolaghi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Baltes PB, Baltes MM. Successful aging: Perspectives from the behavioral sciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1993.

Bowling A. Aspirations for older age in the 21st century: What is successful aging? The International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2007; 64(3):263-97. [DOI:10.2190/L0K1-87W4-9R01-7127] [PMID]

Depp CA, Jeste DV. Definitions and predictors of successful aging: A comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006; 14(1):6-20. [DOI:10.1097/01.JGP.0000192501.03069.bc] [PMID]

Pruchno RA, Wilson-Genderson M, Cartwright F. A two-factor model of successful aging. Journals of Gerontology Series B. 2010; 65(6):671-9. [DOI:10.1093/geronb/gbq051] [PMID]

Havighurst RJ. Successful aging. Processes of aging: Social and psychological perspectives. The Gerontologist. 1963; 1(1):299-320. [DOI:10.1093/geront/1.1.8]

Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Successful aging. The Gerontologist. 1997; 37(4):433-40. [DOI:10.1093/geront/37.4.433]

Crowther MR, Parker MW, Achenbaum WA, Larimore WL, Koenig HG. Rowe and Kahn’s model of successful aging revisited: Positive spirituality-the forgotten factor. The Gerontologist. 2002; 42(5):613-20. [DOI:10.1093/geront/42.5.613] [PMID]

Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Successful aging 2.0: Conceptual expansions for the 21st century. The Journals of Gerontology. 2015; 70(4):593-6. [DOI:10.1093/geronb/gbv025] [PMID]

Baltes PB, Baltes MM. Psychological perspectives on successful aging: The model of selective optimization with compensation. Successful Aging: Perspectives from The Behavioral Sciences. 1990; 1(1):1-34. [DOI:10.1017/CBO9780511665684.003]

Schulz R, Heckhausen J. A life span model of successful aging. American Psychologist. 1996; 51(7):702-14. [DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.51.7.702] [PMID]

Torres S. A culturally-relevant theoretical framework for the study of successful ageing. Ageing & Society. 1999; 19(1):33-51. [DOI:10.1017/S0144686X99007242]

Tornstam L. Gerotranscendence: A developmental theory of positive aging. Berlin: Springer; 2005.

Liang J, Luo B. Toward a discourse shift in social gerontology: From successful aging to harmonious aging. Journal of Aging Studies. 2012; 26(3):327-34. [DOI:10.1016/j.jaging.2012.03.001]

Willcox DC, Willcox BJ, Sokolovsky J, Sakihara S. The cultural context of “successful aging” among older women weavers in a northern Okinawan village: The role of productive activity. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 2007; 22(2):137-65. [DOI:10.1007/s10823-006-9032-0] [PMID]

Whitley E, Popham F, Benzeval M. Comparison of the rowe-kahn model of successful aging with self-rated health and life satisfaction: The west of Scotland twenty-07 prospective cohort study. The Gerontologist. 2016; 56(6):1082-92. [DOI:10.1093/geront/gnv054] [PMID] [PMCID]

Barrett AJ, Murk PJ. Life Satisfaction Index for the Third Age (LSITA): A measurement of successful aging. Indianapolis, Indiana: IUPUI; 2006.

Freund AM, Baltes PB. Life-management strategies of selection, optimization and compensation: Measurement by self-report and construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002; 82(4):642-62. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.82.4.642]

Phelan EA, Anderson LA, Lacroix AZ, Larson EB. Older adults’ views of “successful aging”-how do they compare with researchers’ definitions? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004; 52(2):211-6. [DOI:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52056.x] [PMID]

Troutman M, Nies MA, Small S, Bates A. The development and testing of an instrument to measure successful aging. Research in Gerontological Nursing. 2011; 4(3):221-32. [DOI:10.3928/19404921-20110106-02] [PMID]

Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985; 49(1):71-5. [DOI:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13] [PMID]

Robinson OC. Sampling in interview-based qualitative research: A theoretical and practical guide. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2014; 11(1):25-41. [DOI:10.1080/14780887.2013.801543]

Zanjari N, Sharifian Sani M, Hosseini Chavoshi M, Rafiey H, Mohammadi Shahboulaghi F. Perceptions of successful ageing among Iranian elders: insights from a qualitative study. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2016; 83(4):381-401. [DOI:10.1177/0091415016657559] [PMID]

Zanjari N, Sani MS, Chavoshi MH, Rafiey H, Shahboulaghi FM. Successful aging as a multidimensional concept: An integrative review. Medical journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran. 2017; 31:100. [DOI:10.14196/mjiri.31.100] [PMID] [PMCID]

Onwuegbuzie AJ, Bustamante RM, Nelson JA. Mixed research as a tool for developing quantitative instruments. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2010; 4(1):56-78. [DOI:10.1177/1558689809355805]

Tashakkori A, Teddlie C. Major issues and controversies in the use of mixed methods in the social and behavioral sciences. In: Tashakkori A, and Teddlie C, editors. Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2003.

Fisher BJ. Successful aging and life satisfaction: A pilot study for conceptual clarification. Journal of Aging Studies. 1992; 6(2):191-202. [DOI:10.1016/0890-4065(92)90012-U]

Bowling A, Dieppe P. What is successful ageing and who should define it? BMJ. 2005; 331(7531):1548-51. [DOI:10.1136/bmj.331.7531.1548] [PMID] [PMCID]

Jopp DS, Wozniak D, Damarin AK, De Feo M, Jung S, Jeswani S. How could lay perspectives on successful aging complement scientific theory? Findings from a US and a German life-span sample. The Gerontologist. 2014; 55(1):91-106. [DOI:10.1093/geront/gnu059] [PMID] [PMCID]

Cosco TD, Prina AM, Perales J, Stephan BC, Brayne C. Operational definitions of successful aging: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics. 2014; 26(3):373-81. [DOI:10.1017/S1041610213002287] [PMID]

Cho J, Martin P, Poon LW, Study GC. Successful aging and subjective well-being among oldest-old adults. The Gerontologist. 2014; 55(1):132-43. [DOI:10.1093/geront/gnu074] [PMID] [PMCID]

Martin P, Kelly N, Kahana B, Kahana E, Willcox BJ, Willcox DC, et al. Defining successful aging: A tangible or elusive concept? The Gerontologist. 2014; 55(1):14-25. [DOI:10.1093/geront/gnu044] [PMID] [PMCID]

Martinson M, Berridge C. Successful aging and its discontents: A systematic review of the social gerontology literature. Gerontologist. 2015; 55(1):58-69. [DOI:10.1093/geront/gnu037] [PMID] [PMCID]

Goudarz M, Foroughan M, Makarem A, Rashedi V. [Relationship between social support and subjective well-being in older adults (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2015; 10(3):110-9.

Rashedi V, Gharib M, Rezaei M, Yazdani AA. [Social support and anxiety in the elderly of Hamedan, Iran (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2013; 14(2):110-5.

The extracted 7 factors in our study are documented in the literature as the key dimensions of SA. Cho et al. indicated subjective well-being among oldest old as a dimension of SA [30]. Jopp et al. developed the meaning of SA in sight of the elderly from the United States and Germany in terms of the resources, behaviors, and psychological factors [28]. Martin et al., Martinson et al., and Cosco et al. indicated the bio-psycho-social and environmental aspects of SA concept [29, 31, 32]. Moreover, the previous studies on aging in Iran revealed the importance of psychological well-being and social support dimensions in health and aging well [33, 34].

The convergent validity of the instrument suggested a significant correlation between life satisfaction and the SSAI. This is consistent with a study on the SAI instrument [18]. Regarding the importance of social classes and health status in the scoring of SA [2, 30-32], we tested the known-groups validity. The obtained results indicated lower scores for the elderly with poor health and low socioeconomic status, and vice versa. Thus, the instrument can discriminate social groups. In addition, the SSAI had a high internal reliability (0.93). Moreover, assessing test-retest reliability revealed a significant and high Intra-class correlation coefficient (0.975). Thus, the validity and reliability of SSAI were supported by the data, including content validity, construct validity, known-groups validity, convergent validity, test-retest reliability, and internal consistency.

This study had some limitations. The SSAI was developed using a sample of Iranian elderlies and cultural constructs. Therefore, this instrument needs to be validated in other contexts. In addition, the conceptual framework emerged from an urban context and elderly people living in rural areas were excluded from this research. It is recommended that the SSAI psychometric characteristics be evaluated in different cultural contexts.

5. Conclusion

This study indicated that the SSAI has appropriate content and construct validity. Moreover, the obtained results suggested measuring SA concepts and developing social policies in this area considering all 7 dimensions of SA to cover all the individual (e.g. bio-psychological health), interpersonal (social support), and social (financial and environmental security) needs. In conclusion, the present study supports the validity and reliability of a multidimensional self-perceived instrument for assessing SA. It also provides evidence in the support of the utility of a new instrument to measure SA.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The development of successful ageing instrument was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Funding

This article has been extracted from The PhD. thesis of first author, in Iranian Research Centre on Aging, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and methodology: Nasibeh Zanjari; Supervision: Maryam Sharifian Sani, Meimanat Hosseini Chavoshi; Investigation and draft preparation: Nasibeh Zanjari; and Review and editing: Hassan Rafiey, Farahnaz Mohammadi-Shahbolaghi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Baltes PB, Baltes MM. Successful aging: Perspectives from the behavioral sciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1993.

Bowling A. Aspirations for older age in the 21st century: What is successful aging? The International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2007; 64(3):263-97. [DOI:10.2190/L0K1-87W4-9R01-7127] [PMID]

Depp CA, Jeste DV. Definitions and predictors of successful aging: A comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006; 14(1):6-20. [DOI:10.1097/01.JGP.0000192501.03069.bc] [PMID]

Pruchno RA, Wilson-Genderson M, Cartwright F. A two-factor model of successful aging. Journals of Gerontology Series B. 2010; 65(6):671-9. [DOI:10.1093/geronb/gbq051] [PMID]

Havighurst RJ. Successful aging. Processes of aging: Social and psychological perspectives. The Gerontologist. 1963; 1(1):299-320. [DOI:10.1093/geront/1.1.8]

Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Successful aging. The Gerontologist. 1997; 37(4):433-40. [DOI:10.1093/geront/37.4.433]

Crowther MR, Parker MW, Achenbaum WA, Larimore WL, Koenig HG. Rowe and Kahn’s model of successful aging revisited: Positive spirituality-the forgotten factor. The Gerontologist. 2002; 42(5):613-20. [DOI:10.1093/geront/42.5.613] [PMID]

Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Successful aging 2.0: Conceptual expansions for the 21st century. The Journals of Gerontology. 2015; 70(4):593-6. [DOI:10.1093/geronb/gbv025] [PMID]

Baltes PB, Baltes MM. Psychological perspectives on successful aging: The model of selective optimization with compensation. Successful Aging: Perspectives from The Behavioral Sciences. 1990; 1(1):1-34. [DOI:10.1017/CBO9780511665684.003]

Schulz R, Heckhausen J. A life span model of successful aging. American Psychologist. 1996; 51(7):702-14. [DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.51.7.702] [PMID]

Torres S. A culturally-relevant theoretical framework for the study of successful ageing. Ageing & Society. 1999; 19(1):33-51. [DOI:10.1017/S0144686X99007242]

Tornstam L. Gerotranscendence: A developmental theory of positive aging. Berlin: Springer; 2005.

Liang J, Luo B. Toward a discourse shift in social gerontology: From successful aging to harmonious aging. Journal of Aging Studies. 2012; 26(3):327-34. [DOI:10.1016/j.jaging.2012.03.001]

Willcox DC, Willcox BJ, Sokolovsky J, Sakihara S. The cultural context of “successful aging” among older women weavers in a northern Okinawan village: The role of productive activity. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 2007; 22(2):137-65. [DOI:10.1007/s10823-006-9032-0] [PMID]

Whitley E, Popham F, Benzeval M. Comparison of the rowe-kahn model of successful aging with self-rated health and life satisfaction: The west of Scotland twenty-07 prospective cohort study. The Gerontologist. 2016; 56(6):1082-92. [DOI:10.1093/geront/gnv054] [PMID] [PMCID]

Barrett AJ, Murk PJ. Life Satisfaction Index for the Third Age (LSITA): A measurement of successful aging. Indianapolis, Indiana: IUPUI; 2006.

Freund AM, Baltes PB. Life-management strategies of selection, optimization and compensation: Measurement by self-report and construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002; 82(4):642-62. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.82.4.642]

Phelan EA, Anderson LA, Lacroix AZ, Larson EB. Older adults’ views of “successful aging”-how do they compare with researchers’ definitions? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004; 52(2):211-6. [DOI:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52056.x] [PMID]

Troutman M, Nies MA, Small S, Bates A. The development and testing of an instrument to measure successful aging. Research in Gerontological Nursing. 2011; 4(3):221-32. [DOI:10.3928/19404921-20110106-02] [PMID]

Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985; 49(1):71-5. [DOI:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13] [PMID]

Robinson OC. Sampling in interview-based qualitative research: A theoretical and practical guide. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2014; 11(1):25-41. [DOI:10.1080/14780887.2013.801543]

Zanjari N, Sharifian Sani M, Hosseini Chavoshi M, Rafiey H, Mohammadi Shahboulaghi F. Perceptions of successful ageing among Iranian elders: insights from a qualitative study. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2016; 83(4):381-401. [DOI:10.1177/0091415016657559] [PMID]

Zanjari N, Sani MS, Chavoshi MH, Rafiey H, Shahboulaghi FM. Successful aging as a multidimensional concept: An integrative review. Medical journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran. 2017; 31:100. [DOI:10.14196/mjiri.31.100] [PMID] [PMCID]

Onwuegbuzie AJ, Bustamante RM, Nelson JA. Mixed research as a tool for developing quantitative instruments. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2010; 4(1):56-78. [DOI:10.1177/1558689809355805]

Tashakkori A, Teddlie C. Major issues and controversies in the use of mixed methods in the social and behavioral sciences. In: Tashakkori A, and Teddlie C, editors. Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2003.

Fisher BJ. Successful aging and life satisfaction: A pilot study for conceptual clarification. Journal of Aging Studies. 1992; 6(2):191-202. [DOI:10.1016/0890-4065(92)90012-U]

Bowling A, Dieppe P. What is successful ageing and who should define it? BMJ. 2005; 331(7531):1548-51. [DOI:10.1136/bmj.331.7531.1548] [PMID] [PMCID]

Jopp DS, Wozniak D, Damarin AK, De Feo M, Jung S, Jeswani S. How could lay perspectives on successful aging complement scientific theory? Findings from a US and a German life-span sample. The Gerontologist. 2014; 55(1):91-106. [DOI:10.1093/geront/gnu059] [PMID] [PMCID]

Cosco TD, Prina AM, Perales J, Stephan BC, Brayne C. Operational definitions of successful aging: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics. 2014; 26(3):373-81. [DOI:10.1017/S1041610213002287] [PMID]

Cho J, Martin P, Poon LW, Study GC. Successful aging and subjective well-being among oldest-old adults. The Gerontologist. 2014; 55(1):132-43. [DOI:10.1093/geront/gnu074] [PMID] [PMCID]

Martin P, Kelly N, Kahana B, Kahana E, Willcox BJ, Willcox DC, et al. Defining successful aging: A tangible or elusive concept? The Gerontologist. 2014; 55(1):14-25. [DOI:10.1093/geront/gnu044] [PMID] [PMCID]

Martinson M, Berridge C. Successful aging and its discontents: A systematic review of the social gerontology literature. Gerontologist. 2015; 55(1):58-69. [DOI:10.1093/geront/gnu037] [PMID] [PMCID]

Goudarz M, Foroughan M, Makarem A, Rashedi V. [Relationship between social support and subjective well-being in older adults (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2015; 10(3):110-9.

Rashedi V, Gharib M, Rezaei M, Yazdani AA. [Social support and anxiety in the elderly of Hamedan, Iran (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2013; 14(2):110-5.

Article type: Original Research Articles |

Subject:

Aging Studies

Received: 2018/08/8 | Accepted: 2019/01/2 | Published: 2019/06/1

Received: 2018/08/8 | Accepted: 2019/01/2 | Published: 2019/06/1

Send email to the article author