Volume 17, Issue 4 (December 2019)

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2019, 17(4): 319-330 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Amiri A, Kalantari M, Rezaee M, Akbarzadeh Baghban A, Gharebashloo F. Effect of Child Factors on Parental Attitude Toward Children and Adolescents With Cerebral Palsy in Iran. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2019; 17 (4) :319-330

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-968-en.html

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-968-en.html

Alireza Amiri1

, Minoo Kalantari *2

, Minoo Kalantari *2

, Mehdi Rezaee2

, Mehdi Rezaee2

, Alireza Akbarzadeh Baghban1

, Alireza Akbarzadeh Baghban1

, Farzad Gharebashloo1

, Farzad Gharebashloo1

, Minoo Kalantari *2

, Minoo Kalantari *2

, Mehdi Rezaee2

, Mehdi Rezaee2

, Alireza Akbarzadeh Baghban1

, Alireza Akbarzadeh Baghban1

, Farzad Gharebashloo1

, Farzad Gharebashloo1

1- Physiotherapy Research Center, School of Rehabilitation, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Rehabilitation, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Rehabilitation, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 652 kb]

(1852 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4874 Views)

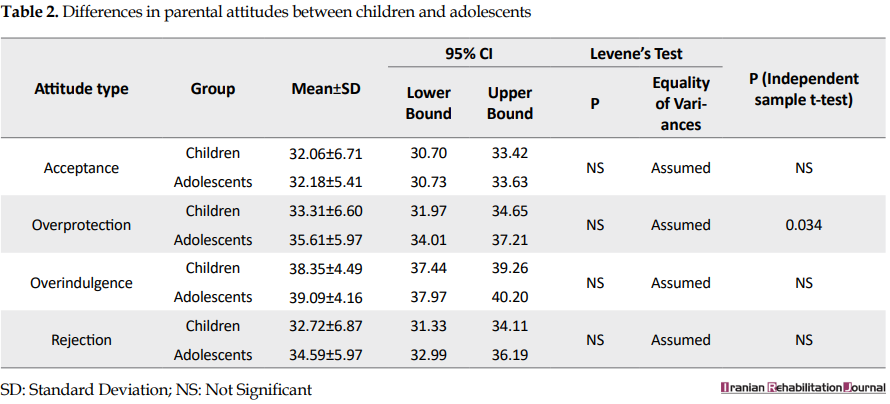

Attitude types are compared between children and adolescents in Table 2. The independent samples t-test showed no significant differences between the age groups except for the overprotection attitude, which was slightly higher among the adolescents (P = 0.034).

Comparison of parental attitude among levels of dependency on motor functions

As shown in Table 3, differences in acceptance and overprotection attitudes were significant among Levels of Dependency in Gross Motor Functions (LDGMF). A gradual decrease in the acceptance scores was observed as the LDGMF increased; however, this was not the case for the overprotection attitude. Overindulgence and rejection attitudes were not statistically significant among LDGMF.

A similar comparison was conducted among Levels of Dependency in Fine Motor Functions (LDFMF). According to the results demonstrated in Table 4, the acceptance attitude was significantly different among LDFMF such that children and adolescents with higher dependency levels were less accepted. The differences in other attitude types were not significant among LDFMFs.

Comparison of parental attitude between ECLs

No significant differences in parental attitudes were observed between ECLs (Table 5).

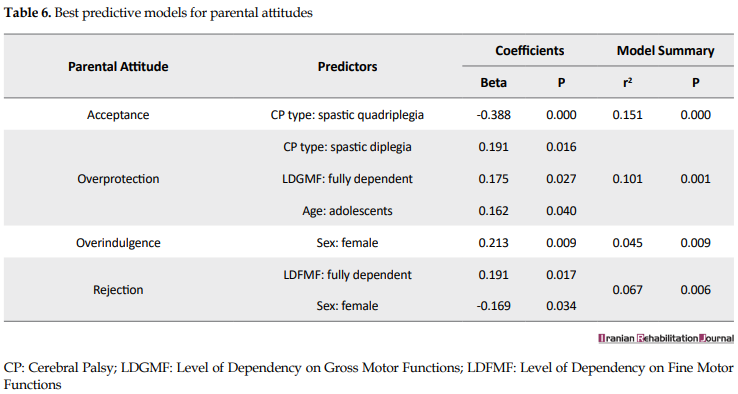

Predictors of parental attitudes

Table 6 presents the best predictive models of child factors for MCRE subscales. According to the results, the best predictor of the acceptance attitude, among child factors, was the type of CP such that children and adolescents with spastic quadriplegia were likely to be less accepted by their mothers. It was also revealed that adolescents with spastic diplegia, who were fully dependent in performing their gross motor functions, were likely to be more overprotected. Further, while the best predictor of the overindulgence attitude was femininity, the rejection attitude was best predicted by not only femininity but also full dependency in fine motor functions as well. Our models could best predict up to 15.1% of the variances in MCRE subscales, indicating that the role of child factors in the prediction of parental attitudes was weak.

4. Discussion

It was found in this study that the overindulgence and the overprotection attitudes were the most common attitudes among mothers of children and adolescents with CP in Iran. These results were in disagreement with those reported by Olawale et al. [34], who demonstrated that parents generally held positive attitudes toward their children with CP and those reported by Jankowska et al. [18], who indicated that the acceptance attitude was the most common attitude among mothers of children with CP. However, congruent with our findings, the latter study pointed out that mothers of children with CP also had a stronger tendency toward overprotective and demanding attitudes compared to mothers of children with typical development. Since parents of children with disabilities tend to perceive their children as more vulnerable and dependent [35], it is assumed that harm reduction could be the dominant motivation in parental overprotectiveness [36]. Of note, the overprotection attitude was more dominant toward adolescents than children in our study; Our models of prediction also indicate that adolescents are more likely to be overprotected. It is understandable that as children with disabilities grow, their activity limitations become more prominent compared to their peers with typical development. This might be a possible cause leading parents to perceive their child as more vulnerable, thus develope more overprotective attitudes. The predictive models also demonstrated that those who depend on their parents to perform their gross motor functions, are more likely to be overprotected. Conceivably, motor function limitations cause mothers to perceive their child as requiring constant protection; however, this was only true for limitations in gross motor functions and not for limitations in fine motor functions. Considering that spastic diplegia is also one of the predictive factors of the overprotection attitude, it can be understood that limitations in walking are the prominent causes of overprotection attitude.

Similar to the overprotection attitude, the acceptance attitude was significantly different among levels of dependency in gross and fine motor functions. Congruent with expectations, those who were more dependent on others to perform their gross and fine motor functions were less accepted by their mothers. The best predictor variable, among the child factors, for the acceptance attitude proved to be the child’s CP type; children and adolescents with spastic quadriplegia are predicted to be less accepted by their mothers. The LDGMF and the LDFMF were not individually significant in the prediction of the acceptance attitude but contributed to the total explained variance of the model. Similarly, the results reported by Al-Dababneh and Al-Zboon demonstrated that with increasing the level of disability, there was an increase in parental negative attitude [12].

While our predictive models showed that increasing dependency in gross motor functions was more likely to be reacted by overprotection attitude, increasing dependency in fine motor functions was more likely to be followed by the rejection attitude. In other words, children and adolescents with limitations in handling objects are more likely to face rejection attitude, while those with walking limitations are more likely to be overprotected. Another predictor variable of the rejection attitude was determined to be the femininity of the child such that girls were less likely to face rejection attitude. This finding is somewhat in disagreement with those reported by Omoniyi et al., who demonstrated that parents tend to present more positive attitudes toward boys [22].

The fact that girls of our study were treated more overindulgent by their mothers highlights this disagreement. This discrepancy might be a culturally-related matter, albeit this cannot be concluded solely based on our results. It is also noteworthy that Al-Dababneh and Al-Zboon [12] reported that the sex of the child was not significantly associated with their parents’ attitudes toward them.

Regarding the cognitive functions, related literature assumed that the child’s delayed cognitive development could influence the parental attitude [18]. However, it was found in our study that parental attitudes were not different between cognitively normal participants and those with mild cognitive disabilities. Contrary to the results of the present study, Awan and Awan reported that parents show more positive attitudes toward their mentally-disabled children [17]. Albeit, our sample did not include children and adolescents with severe cognitive disabilities, and perhaps with the inclusion of this group, different results could be observed.

As stated earlier in this article, parental attitudes other than acceptance are linked to a variety of psychosocial issues, including anxiety, depression, school failures, and conduct problems, either in childhood or later in adolescence. This study showed that the most common attitudes among mothers of children and adolescents with CP are overindulgence and overprotection. These findings emphasize that it is essential to provide parents with adequate knowledge about the psychosocial problems that might be associated with their attitudes toward their child and that interventions should not be limited to intensive rehabilitation services. Alongside the rehabilitation interventions on the child, it is necessary for parents to acquire adequate knowledge about appropriate parenting styles in order to promote the psychosocial health of their child and prevent the potential issues associated with negative parental attitudes.

Lastly, according to the predictive models presented in this article, child factors proved to be a weak predictor of parental attitudes; in other words, only a small proportion of the parental attitudes are influenced by these factors. Therefore, contrary to the expectations, child factors of children and adolescents with CP, including their disability status, are not the most significant determinants of parental attitudes toward them. Considering the importance of parental attitudes in the psychosocial health of children and adolescents, further research is needed to specify the main determinants of the parental attitude toward children and adolescents with CP in Iran.

This study had some limitations, including (i) the range of IQ did not include severe cognitive disabilities, (ii) none of the participants got a diagnosis of dyskinetic, ataxic, or mixed CP, and (iii) the predictor variables could include a broader range of child factors, including the child’s communication functions. This study also featured some strengths, including: (i) this study was the first one investigating the role of child factors in the prediction of parental attitude among Iranian children and adolescents with CP, and (ii) the sample size of this study was large enough to generalize the results to the larger communities of children and adolescents between 7 and 17 years with CP.

5. Conclusion

Most of the mothers of children and adolescents with CP parent their child with overindulgence or overprotection attitudes. Parental attitudes can vary based on the child’s factors, but generally, child factors can only influence a small proportion of parental attitudes. Contrary to the expectations, these factors, including the child’s disability status, are not major determinants of the parental attitudes toward children and adolescents with CP and further research is needed to specify the more prominent determinants.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Ethics Code: IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1396.641). Informed consent was obtained from all human adult participants and the parents or legal guardians of minors.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally in the preparation of this article; Supervision: Minoo Kalantari.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

Full-Text: (1763 Views)

1. Introduction

The term Cerebral Palsy (CP) refers to a group of permanent disorders of the developing brain, mostly recognized by disturbances in the movement and posture. However, motor disorders of CP are often accompanied by impairments in sensation, perception, and cognition abilities that result in activity limitations, communication difficulties, and behavioral issues [1]. Consequently, children and adolescents with CP experience participation restrictions [2], decreased quality of life [3], and mental health disorders [4].

Various characteristics of CP make the parenting of children and adolescents with CP challenging and impose a burden on their parents [5, 6]; in this way, they experience significantly poorer satisfaction with life and psychosocial well-being compared to the parents of children with typical development [7]. Reports also indicate that parenting of these children involves more stress [8], anxiety, and depression [9] and anxious parents are more likely to have anxious children [10]. Since the emotional well-being of parents may influence their parenting attitudes toward their children [11], the inherent distress of raising a child with CP may induce negative parental attitude toward the child [12] and result in poorer marital relationships [13]. Negative attitudes toward disability, either from parents or others, only add to the stress levels of the family [12]. According to Roth’s Mother-Child Relationship Evaluation (MCRE) [14], parental attitudes other than acceptance are considered negative and consist of rejection, overprotection, and overindulgence.

Parental unconditional acceptance, respect, and democratic cooperation with the child make substantial contributions to the child’s psychosocial development [15]. Besides, positive perceptions of children with disabilities can be an effective coping strategy [16]. Although acceptance is the most common parental attitude among mothers of children with CP [12, 17, 18], they have a stronger tendency toward overprotectiveness and demanding attitudes compared to mothers of children with typical development [18]. Attitudes other than acceptance are linked to a variety of psychosocial issues among children and adolescents. Parental overprotection has been consistently associated with child anxiety symptoms and disorders [19]. Indulgent parenting, on the other hand, is related to some adolescent behavioral problems such as conduct problems, delinquency, and aggressive-disruptive behaviors [20]. The rejection attitude is also linked to a variety of psychosocial problems, including depression, externalizing problems, and school failures [21]. Therefore, parental attitudes play an essential role in the development of children and adolescents with CP.

Studies to date reveal that a variety of factors influences parental attitudes toward children and adolescents with disabilities. According to Omoniyi, the gender of the child with a disability influences what attitudes their parents take toward them [22]. Their results indicated that fathers exhibit more favorable attitudes toward boys. Mothers’ attitudes were also in favor of boys in the domains of overprotection and acceptance. Birth order is another associated factor with the parental attitude, such that the first children experience more favorable attitudes from their parents compared to those who are born later [23]. As for age, parents have more positive attitudes toward younger children [17]. The severity of the disability has also been reported to be associated with negative parental attitudes toward children with CP [24].

Despite the pivotal role of the parental attitudes in the psychosocial development of children and adolescents with CP, current literature provides insufficient amounts of information regarding the subject in question and its associated factors [12]. Not to mention, parental attitude is conceivably subject to culture [25], yet no studies to date have investigated the associated factors of parental attitude toward children and adolescents with CP in Iranian culture. Thus, the present study aims to explain the predictive role of child factors (e.g. age, gender, type of CP, level of dependency in gross and fine motor functions, and IQ) in the parental attitudes toward children and adolescents with CP in Iran.

2. Methods

Participants

The target population was all children and adolescents between the ages of 7 and 17 with an IQ above 50 (according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) [10] in Bojnurd, Iran. The sample size was estimated to be 150 individuals, using Cochran’s method. To recruit the study sample, the medical records of 718 individuals diagnosed with CP were obtained from the Special Education Organization and the Social Welfare Organization of Bojnurd, Iran. Among them, 476 children and adolescents met the inclusion criteria. The study sample met the following inclusion criteria: (i) Being between 7 and 17 years old; (ii) Having an IQ above 50 (according to ICD 10); (iii) Having a mother aged at least 25 years as their primary caregiver; (iv) Willingly giving written consent (their parent).

Those who had the following criteria were excluded from the study: (i) Mothers with a history of any psychiatric disorder; (ii) Unwilling to continue the study; (iii) Questionnaires with any missing data. The study sample consisted of 163 children and adolescents who were selected using a systematic random sampling method from those who met the inclusion criteria. Participants between 7 and12 years were grouped as children, and the rest were grouped as adolescents in this study.

Procedure

The cross-sectional study design was used. The data collection process took place in participants’ homes. It started in March 2017 and ended in June 2017. Once written consent was given, the participating children and adolescents were categorized into 3 groups based on their CP type: (i) spastic quadriplegia; (ii) spastic diplegia; (iii) spastic hemiplegia; (iv) other. Their diagnosis of CP had been already confirmed by a neurologist. Demographic information, including the age and sex of the child, was recorded. Then, an occupational therapist classified the gross and fine motor functions of the child/adolescent according to the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) [26] and Manual Ability Classification System (MACS) [27], respectively. Meanwhile, mothers completed the Roth’s Mother-Child Relationship Evaluation (MCRE) questionnaire [14] and the Estimated Cognitive Level (ECL) short form [28].

Measures and predictor variables

The parental attitude was assessed by the MCRE questionnaire. It is a brief self-report measure designed to assess both normal and problematic aspects of parental attitude. The MCRE consists of 4 subscales, 12 items each: (i) Acceptance, (ii) Overprotection, (iii) Overindulgence, and (iv) Rejection. Mothers are asked to rate their agreement or disagreement with each item based on a 5-point Likert scale. Sum-scores of each subscale are independent of another, and the outcome of the questionnaire describes the parental attitude by 4 separate scores. There is no overall score for the MCRE. The questionnaire had been translated into the Persian language, and its validity and reliability had been tested on 30 individuals in 2005 [29]. The Cronbach’s alpha of the 4 subscales of the test were within the range of acceptable values: (i) Acceptance=0.77, (ii) Rejection=0.72, (iii) Overindulgence=0.71, and (iv) Overprotection=0.78. It had also been reported that this measure is applicable to mothers of children with a disability too [30].

The ECL of the participating children and adolescents was determined, using the ECL form, which is a part of the impairment form of the SPARCLE project [31]. It is a parent-report measure that estimates the IQ of the child/adolescent according to ICD 10. This measure classifies IQ to 3 levels: (i) severe cognitive disability (IQ<50), (ii) mild cognitive disability (50≤IQ<70), and (iii) normal (70≤IQ).

To assess the level of dependency in gross and fine motor functions, the Persian versions of the GMFCS and the MACS were used, respectively. To that end, the levels of both GMFCS and MACS were reclassified as follow: (i) Independent in gross motor functions (GMFCS levels I and II), (ii) Moderately dependent in gross motor functions (GMFC levels III and IV), (iii) Fully dependent in gross motor functions (GMFCS level V), (iv) Independent in fine motor functions (MACS levels I and II), (v) Moderately dependent in fine motor functions (MACS levels III and IV), and (vi) Fully dependent in fine motor functions (MACS level V). The validity and reliability of the Persian versions of these measures had been tested, and they had been evaluated as suitable for application on the Iranian population [32, 33].

The subset of child factors, which was selected as potential predictors of parental attitude, included biomedical status (based on CP type), level of dependency in gross motor functions (based on GMFCS), level of dependency in fine motor functions (based on MACS), cognitive functions (based on ECL), age, and sex.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were performed to describe parental attitudes toward children and adolescents with CP. The independent samples t-test was used to investigate the differences in parental attitudes between the children and the adolescents and also between two levels of participants’ ECL. The One-way ANOVA test was performed to investigate the differences in parental attitudes among levels of dependency in gross/fine motor functions. Simple and multiple linear regressions were performed to determine the predictive role of child factors in parental attitudes. All statistical analyses were performed by the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 16.0.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (ethics code: IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1396.641). Informed consent was obtained from all human adult participants and the parents or legal guardians of minors.

3. Results

Participants’ characteristics

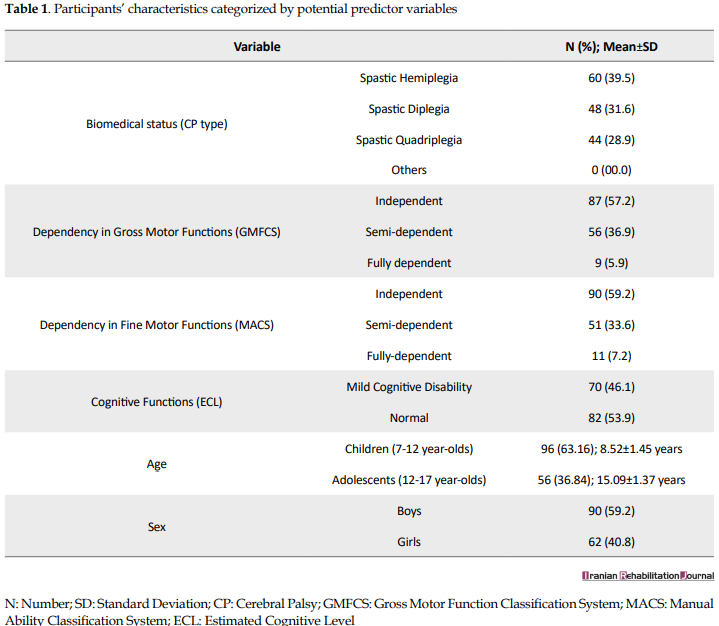

Of 163 potential participants, 11 (6.75%) individuals were excluded according to the exclusion criteria: (i) mothers with a history of any psychiatric disorder (n = 4), (ii) unwilling to continue the study (n = 4), (iii) and questionnaires with missing data (n = 3). Table 1 presents the participant’s characteristics.

Comparison of parental attitude between children and adolescents

The term Cerebral Palsy (CP) refers to a group of permanent disorders of the developing brain, mostly recognized by disturbances in the movement and posture. However, motor disorders of CP are often accompanied by impairments in sensation, perception, and cognition abilities that result in activity limitations, communication difficulties, and behavioral issues [1]. Consequently, children and adolescents with CP experience participation restrictions [2], decreased quality of life [3], and mental health disorders [4].

Various characteristics of CP make the parenting of children and adolescents with CP challenging and impose a burden on their parents [5, 6]; in this way, they experience significantly poorer satisfaction with life and psychosocial well-being compared to the parents of children with typical development [7]. Reports also indicate that parenting of these children involves more stress [8], anxiety, and depression [9] and anxious parents are more likely to have anxious children [10]. Since the emotional well-being of parents may influence their parenting attitudes toward their children [11], the inherent distress of raising a child with CP may induce negative parental attitude toward the child [12] and result in poorer marital relationships [13]. Negative attitudes toward disability, either from parents or others, only add to the stress levels of the family [12]. According to Roth’s Mother-Child Relationship Evaluation (MCRE) [14], parental attitudes other than acceptance are considered negative and consist of rejection, overprotection, and overindulgence.

Parental unconditional acceptance, respect, and democratic cooperation with the child make substantial contributions to the child’s psychosocial development [15]. Besides, positive perceptions of children with disabilities can be an effective coping strategy [16]. Although acceptance is the most common parental attitude among mothers of children with CP [12, 17, 18], they have a stronger tendency toward overprotectiveness and demanding attitudes compared to mothers of children with typical development [18]. Attitudes other than acceptance are linked to a variety of psychosocial issues among children and adolescents. Parental overprotection has been consistently associated with child anxiety symptoms and disorders [19]. Indulgent parenting, on the other hand, is related to some adolescent behavioral problems such as conduct problems, delinquency, and aggressive-disruptive behaviors [20]. The rejection attitude is also linked to a variety of psychosocial problems, including depression, externalizing problems, and school failures [21]. Therefore, parental attitudes play an essential role in the development of children and adolescents with CP.

Studies to date reveal that a variety of factors influences parental attitudes toward children and adolescents with disabilities. According to Omoniyi, the gender of the child with a disability influences what attitudes their parents take toward them [22]. Their results indicated that fathers exhibit more favorable attitudes toward boys. Mothers’ attitudes were also in favor of boys in the domains of overprotection and acceptance. Birth order is another associated factor with the parental attitude, such that the first children experience more favorable attitudes from their parents compared to those who are born later [23]. As for age, parents have more positive attitudes toward younger children [17]. The severity of the disability has also been reported to be associated with negative parental attitudes toward children with CP [24].

Despite the pivotal role of the parental attitudes in the psychosocial development of children and adolescents with CP, current literature provides insufficient amounts of information regarding the subject in question and its associated factors [12]. Not to mention, parental attitude is conceivably subject to culture [25], yet no studies to date have investigated the associated factors of parental attitude toward children and adolescents with CP in Iranian culture. Thus, the present study aims to explain the predictive role of child factors (e.g. age, gender, type of CP, level of dependency in gross and fine motor functions, and IQ) in the parental attitudes toward children and adolescents with CP in Iran.

2. Methods

Participants

The target population was all children and adolescents between the ages of 7 and 17 with an IQ above 50 (according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) [10] in Bojnurd, Iran. The sample size was estimated to be 150 individuals, using Cochran’s method. To recruit the study sample, the medical records of 718 individuals diagnosed with CP were obtained from the Special Education Organization and the Social Welfare Organization of Bojnurd, Iran. Among them, 476 children and adolescents met the inclusion criteria. The study sample met the following inclusion criteria: (i) Being between 7 and 17 years old; (ii) Having an IQ above 50 (according to ICD 10); (iii) Having a mother aged at least 25 years as their primary caregiver; (iv) Willingly giving written consent (their parent).

Those who had the following criteria were excluded from the study: (i) Mothers with a history of any psychiatric disorder; (ii) Unwilling to continue the study; (iii) Questionnaires with any missing data. The study sample consisted of 163 children and adolescents who were selected using a systematic random sampling method from those who met the inclusion criteria. Participants between 7 and12 years were grouped as children, and the rest were grouped as adolescents in this study.

Procedure

The cross-sectional study design was used. The data collection process took place in participants’ homes. It started in March 2017 and ended in June 2017. Once written consent was given, the participating children and adolescents were categorized into 3 groups based on their CP type: (i) spastic quadriplegia; (ii) spastic diplegia; (iii) spastic hemiplegia; (iv) other. Their diagnosis of CP had been already confirmed by a neurologist. Demographic information, including the age and sex of the child, was recorded. Then, an occupational therapist classified the gross and fine motor functions of the child/adolescent according to the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) [26] and Manual Ability Classification System (MACS) [27], respectively. Meanwhile, mothers completed the Roth’s Mother-Child Relationship Evaluation (MCRE) questionnaire [14] and the Estimated Cognitive Level (ECL) short form [28].

Measures and predictor variables

The parental attitude was assessed by the MCRE questionnaire. It is a brief self-report measure designed to assess both normal and problematic aspects of parental attitude. The MCRE consists of 4 subscales, 12 items each: (i) Acceptance, (ii) Overprotection, (iii) Overindulgence, and (iv) Rejection. Mothers are asked to rate their agreement or disagreement with each item based on a 5-point Likert scale. Sum-scores of each subscale are independent of another, and the outcome of the questionnaire describes the parental attitude by 4 separate scores. There is no overall score for the MCRE. The questionnaire had been translated into the Persian language, and its validity and reliability had been tested on 30 individuals in 2005 [29]. The Cronbach’s alpha of the 4 subscales of the test were within the range of acceptable values: (i) Acceptance=0.77, (ii) Rejection=0.72, (iii) Overindulgence=0.71, and (iv) Overprotection=0.78. It had also been reported that this measure is applicable to mothers of children with a disability too [30].

The ECL of the participating children and adolescents was determined, using the ECL form, which is a part of the impairment form of the SPARCLE project [31]. It is a parent-report measure that estimates the IQ of the child/adolescent according to ICD 10. This measure classifies IQ to 3 levels: (i) severe cognitive disability (IQ<50), (ii) mild cognitive disability (50≤IQ<70), and (iii) normal (70≤IQ).

To assess the level of dependency in gross and fine motor functions, the Persian versions of the GMFCS and the MACS were used, respectively. To that end, the levels of both GMFCS and MACS were reclassified as follow: (i) Independent in gross motor functions (GMFCS levels I and II), (ii) Moderately dependent in gross motor functions (GMFC levels III and IV), (iii) Fully dependent in gross motor functions (GMFCS level V), (iv) Independent in fine motor functions (MACS levels I and II), (v) Moderately dependent in fine motor functions (MACS levels III and IV), and (vi) Fully dependent in fine motor functions (MACS level V). The validity and reliability of the Persian versions of these measures had been tested, and they had been evaluated as suitable for application on the Iranian population [32, 33].

The subset of child factors, which was selected as potential predictors of parental attitude, included biomedical status (based on CP type), level of dependency in gross motor functions (based on GMFCS), level of dependency in fine motor functions (based on MACS), cognitive functions (based on ECL), age, and sex.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were performed to describe parental attitudes toward children and adolescents with CP. The independent samples t-test was used to investigate the differences in parental attitudes between the children and the adolescents and also between two levels of participants’ ECL. The One-way ANOVA test was performed to investigate the differences in parental attitudes among levels of dependency in gross/fine motor functions. Simple and multiple linear regressions were performed to determine the predictive role of child factors in parental attitudes. All statistical analyses were performed by the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 16.0.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (ethics code: IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1396.641). Informed consent was obtained from all human adult participants and the parents or legal guardians of minors.

3. Results

Participants’ characteristics

Of 163 potential participants, 11 (6.75%) individuals were excluded according to the exclusion criteria: (i) mothers with a history of any psychiatric disorder (n = 4), (ii) unwilling to continue the study (n = 4), (iii) and questionnaires with missing data (n = 3). Table 1 presents the participant’s characteristics.

Comparison of parental attitude between children and adolescents

Attitude types are compared between children and adolescents in Table 2. The independent samples t-test showed no significant differences between the age groups except for the overprotection attitude, which was slightly higher among the adolescents (P = 0.034).

Comparison of parental attitude among levels of dependency on motor functions

As shown in Table 3, differences in acceptance and overprotection attitudes were significant among Levels of Dependency in Gross Motor Functions (LDGMF). A gradual decrease in the acceptance scores was observed as the LDGMF increased; however, this was not the case for the overprotection attitude. Overindulgence and rejection attitudes were not statistically significant among LDGMF.

A similar comparison was conducted among Levels of Dependency in Fine Motor Functions (LDFMF). According to the results demonstrated in Table 4, the acceptance attitude was significantly different among LDFMF such that children and adolescents with higher dependency levels were less accepted. The differences in other attitude types were not significant among LDFMFs.

Comparison of parental attitude between ECLs

No significant differences in parental attitudes were observed between ECLs (Table 5).

Predictors of parental attitudes

Table 6 presents the best predictive models of child factors for MCRE subscales. According to the results, the best predictor of the acceptance attitude, among child factors, was the type of CP such that children and adolescents with spastic quadriplegia were likely to be less accepted by their mothers. It was also revealed that adolescents with spastic diplegia, who were fully dependent in performing their gross motor functions, were likely to be more overprotected. Further, while the best predictor of the overindulgence attitude was femininity, the rejection attitude was best predicted by not only femininity but also full dependency in fine motor functions as well. Our models could best predict up to 15.1% of the variances in MCRE subscales, indicating that the role of child factors in the prediction of parental attitudes was weak.

4. Discussion

It was found in this study that the overindulgence and the overprotection attitudes were the most common attitudes among mothers of children and adolescents with CP in Iran. These results were in disagreement with those reported by Olawale et al. [34], who demonstrated that parents generally held positive attitudes toward their children with CP and those reported by Jankowska et al. [18], who indicated that the acceptance attitude was the most common attitude among mothers of children with CP. However, congruent with our findings, the latter study pointed out that mothers of children with CP also had a stronger tendency toward overprotective and demanding attitudes compared to mothers of children with typical development. Since parents of children with disabilities tend to perceive their children as more vulnerable and dependent [35], it is assumed that harm reduction could be the dominant motivation in parental overprotectiveness [36]. Of note, the overprotection attitude was more dominant toward adolescents than children in our study; Our models of prediction also indicate that adolescents are more likely to be overprotected. It is understandable that as children with disabilities grow, their activity limitations become more prominent compared to their peers with typical development. This might be a possible cause leading parents to perceive their child as more vulnerable, thus develope more overprotective attitudes. The predictive models also demonstrated that those who depend on their parents to perform their gross motor functions, are more likely to be overprotected. Conceivably, motor function limitations cause mothers to perceive their child as requiring constant protection; however, this was only true for limitations in gross motor functions and not for limitations in fine motor functions. Considering that spastic diplegia is also one of the predictive factors of the overprotection attitude, it can be understood that limitations in walking are the prominent causes of overprotection attitude.

Similar to the overprotection attitude, the acceptance attitude was significantly different among levels of dependency in gross and fine motor functions. Congruent with expectations, those who were more dependent on others to perform their gross and fine motor functions were less accepted by their mothers. The best predictor variable, among the child factors, for the acceptance attitude proved to be the child’s CP type; children and adolescents with spastic quadriplegia are predicted to be less accepted by their mothers. The LDGMF and the LDFMF were not individually significant in the prediction of the acceptance attitude but contributed to the total explained variance of the model. Similarly, the results reported by Al-Dababneh and Al-Zboon demonstrated that with increasing the level of disability, there was an increase in parental negative attitude [12].

While our predictive models showed that increasing dependency in gross motor functions was more likely to be reacted by overprotection attitude, increasing dependency in fine motor functions was more likely to be followed by the rejection attitude. In other words, children and adolescents with limitations in handling objects are more likely to face rejection attitude, while those with walking limitations are more likely to be overprotected. Another predictor variable of the rejection attitude was determined to be the femininity of the child such that girls were less likely to face rejection attitude. This finding is somewhat in disagreement with those reported by Omoniyi et al., who demonstrated that parents tend to present more positive attitudes toward boys [22].

The fact that girls of our study were treated more overindulgent by their mothers highlights this disagreement. This discrepancy might be a culturally-related matter, albeit this cannot be concluded solely based on our results. It is also noteworthy that Al-Dababneh and Al-Zboon [12] reported that the sex of the child was not significantly associated with their parents’ attitudes toward them.

Regarding the cognitive functions, related literature assumed that the child’s delayed cognitive development could influence the parental attitude [18]. However, it was found in our study that parental attitudes were not different between cognitively normal participants and those with mild cognitive disabilities. Contrary to the results of the present study, Awan and Awan reported that parents show more positive attitudes toward their mentally-disabled children [17]. Albeit, our sample did not include children and adolescents with severe cognitive disabilities, and perhaps with the inclusion of this group, different results could be observed.

As stated earlier in this article, parental attitudes other than acceptance are linked to a variety of psychosocial issues, including anxiety, depression, school failures, and conduct problems, either in childhood or later in adolescence. This study showed that the most common attitudes among mothers of children and adolescents with CP are overindulgence and overprotection. These findings emphasize that it is essential to provide parents with adequate knowledge about the psychosocial problems that might be associated with their attitudes toward their child and that interventions should not be limited to intensive rehabilitation services. Alongside the rehabilitation interventions on the child, it is necessary for parents to acquire adequate knowledge about appropriate parenting styles in order to promote the psychosocial health of their child and prevent the potential issues associated with negative parental attitudes.

Lastly, according to the predictive models presented in this article, child factors proved to be a weak predictor of parental attitudes; in other words, only a small proportion of the parental attitudes are influenced by these factors. Therefore, contrary to the expectations, child factors of children and adolescents with CP, including their disability status, are not the most significant determinants of parental attitudes toward them. Considering the importance of parental attitudes in the psychosocial health of children and adolescents, further research is needed to specify the main determinants of the parental attitude toward children and adolescents with CP in Iran.

This study had some limitations, including (i) the range of IQ did not include severe cognitive disabilities, (ii) none of the participants got a diagnosis of dyskinetic, ataxic, or mixed CP, and (iii) the predictor variables could include a broader range of child factors, including the child’s communication functions. This study also featured some strengths, including: (i) this study was the first one investigating the role of child factors in the prediction of parental attitude among Iranian children and adolescents with CP, and (ii) the sample size of this study was large enough to generalize the results to the larger communities of children and adolescents between 7 and 17 years with CP.

5. Conclusion

Most of the mothers of children and adolescents with CP parent their child with overindulgence or overprotection attitudes. Parental attitudes can vary based on the child’s factors, but generally, child factors can only influence a small proportion of parental attitudes. Contrary to the expectations, these factors, including the child’s disability status, are not major determinants of the parental attitudes toward children and adolescents with CP and further research is needed to specify the more prominent determinants.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Ethics Code: IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1396.641). Informed consent was obtained from all human adult participants and the parents or legal guardians of minors.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally in the preparation of this article; Supervision: Minoo Kalantari.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Rosenbaum P, Paneth N, Leviton A, Goldstein M, Bax M, Damiano D, et al. A report: The definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology; 109 (suppl. 109):8-14.

- Woodmansee C, Hahne A, Imms C, Shields N. Comparing participation in physical recreation activities between children with disability and children with typical development: A secondary analysis of matched data. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2016; 49-50:268-76. [DOI:10.1016/j.ridd.2015.12.004] [PMID]

- Colver A, Rapp M, Eisemann N, Ehlinger V, Thyen U, Dickinson HO, et al. Self-reported quality of life of adolescents with cerebral palsy: A cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis. Lancet. 2015; 385(9969):705-16. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61229-0]

- Downs J, Blackmore AM, Epstein A, Skoss R, Langdon K, Jacoby P, et al. The prevalence of mental health disorders and symptoms in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2018; 60(1):30-8. [DOI:10.1111/dmcn.13555] [PMID]

- Plant KM, Sanders MR. Predictors of care‐giver stress in families of preschool‐aged children with developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities. 2007; 51(2):109-24. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00829.x] [PMID]

- Santos MTBR, Biancardi M, Guare RO, Jardim JR. Caries prevalence in patients with cerebral palsy and the burden of caring for them. Special Care in Dentistry. 2010; 30(5):206-10. [DOI:10.1111/j.1754-4505.2010.00151.x] [PMID]

- Cheshire A, Barlow JH, Powell LA. The psychosocial well-being of parents of children with cerebral palsy: A comparison study. Disability and rehabilitation. 2010; 32(20):1673-7. [DOI:10.3109/09638281003649920] [PMID]

- Ones K, Yilmaz E, Cetinkaya B, Caglar N. Assessment of the quality of life of mothers of children with cerebral palsy (primary caregivers). Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2005; 19(3):232-7. [DOI:10.1177/1545968305278857] [PMID]

- Barlow JH, Cullen‐Powell LA, Cheshire A. Psychological well‐being among mothers of children with cerebral palsy. Early Child Development Care. 2006; 176(3-4):421-8. [DOI:10.1080/0300443042000313403]

- Ginsburg GS, Grover RL, Ialongo N. Parenting behaviors among anxious and non-anxious mothers: Relation with concurrent and long-term child outcomes. Child & Family Behavior Therapy. 2005; 26(4):23-41. [DOI:10.1300/J019v26n04_02]

- Yurduşen S, Erol N, Gençöz T. The effects of parental attitudes and mothers’ psychological well-being on the emotional and behavioral problems of their preschool children. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2013; 17(1):68-75. [DOI:10.1007/s10995-012-0946-6] [PMID]

- Al-Dababneh KA, Al-Zboon EK. Parents’ attitudes towards their children with cerebral palsy. Early Child Development and Care. 2018; 188(6):731-47. [DOI:10.1080/03004430.2016.1230737]

- Abasiubong F, Ansa VO, Udoh SB, Edemekong II, Akpan MU. Stress, Attitude and Marital Relationships of Mothers of children with Chronic Neurological Disorders in Southern Nigeria. TAF Preventive Medicine Bulletin. 2010; 9(5):413-20

- Roth RM. Mother-Child Relationship Evaluation: California: WPS; 1969.

- Jankowska AM, Takagi A, Bogdanowicz M, Jonak J. Parenting style and locus of control, motivation, and school adaptation among students with Borderline Intellectual Functioning. Current Issues in Personality Psychology. 2014; 2(4):251-66. [DOI:10.5114/cipp.2014.47448]

- Gupta A, Singhal N. Positive perceptions in parents of children with disabilities. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal. 2004; 15(1):22-35.

- Awan IH, Awan SN. Parents’ Attitude Towards Mentally Retarded Children. Journal Of Social Science Research. 2014; 1(1):31-51.

- Jankowska AM, Włodarczyk A, Campbell C, Shaw S. Parental attitudes and personality traits, self-efficacy, stress, and coping strategies among mothers of children with cerebral palsy. Health Psychology Report. 2015; 3(3):246-59. [DOI:10.5114/hpr.2015.51903]

- Clarke K, Cooper P, Creswell C. The Parental Overprotection Scale: Associations with child and parental anxiety. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013; 151(2):618-24. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2013.07.007] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Cui M, Graber JA, Metz A, Darling CA. Parental indulgence, self-regulation, and young adults’ behavioral and emotional problems. Journal of Family Studies. 2016; 25(3):1-17. [DOI:10.1080/13229400.2016.1237884]

- Miranda MC, Affuso G, Esposito C, Bacchini D. Parental acceptance-rejection and adolescent maladjustment: Mothers’ and fathers’ combined roles. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2016; 25(4):1352-62. [DOI:10.1007/s10826-015-0305-5]

- Omoniyi MBI. Parental Attitude towards Disability and Gender in the Nigerian Context: Implications for Conselling. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences. 2014; 5(20):1-6. [DOI:10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n20p2255]

- Kumar S, Rao G. Parental attitudes towards children with hearing impairment. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal. 2008; 19(2):111-7.

- Colver AF, Dickinson HO, Parkinson K, Arnaud C, Beckung E, Fauconnier J, et al. Access of children with cerebral palsy to the physical, social and attitudinal environment they need: A cross-sectional European study. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2011; 33(1):28-35. [DOI:10.3109/09638288.2010.485669] [PMID]

- Dalal AK, Pande N. Cultural beliefs and family care of the children with disability. Psychology and Developing Societies. 1999; 11(1):55-75. [DOI:10.1177/097133369901100103]

- Rosenbaum PL, Palisano RJ, Bartlett DJ, Galuppi BE, Russell DJ. Development of the gross motor function classification system for cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology (DMCN). 2008; 50(4):249-53. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.02045.x] [PMID]

- Eliasson A-C, Krumlinde-Sundholm L, Rösblad B, Beckung E, Arner M, Öhrvall A-M, et al. The Manual Ability Classification System (MACS) for children with cerebral palsy: Scale development and evidence of validity and reliability. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology (DMCN). 2006; 48(7):549-54. [DOI:10.1017/S0012162206001162] [PMID]

- Gunel MK, Mutlu A, Tarsuslu T, Livanelioglu A. Relationship among the Manual Ability Classification System (MACS), the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS), and the functional status (WeeFIM) in children with spastic cerebral palsy. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2009; 168(4):477-85. [DOI:10.1007/s00431-008-0775-1] [PMID]

- Khanjani Z, Peymannia B, Hashemi T, Aghagolzadeh M. Relationship between the quality of mother-child interaction, separation anxiety and school Phobia in children. The Journal of Urmia University of Medical Sciences . 2014; 25(3):231-40.

- Jillings CR, Adamson CA, Russell T. An Application of Roth’s Mother-Child Relationship Evaluation to Some Mothers of Handicapped Children. Psychological Reports. 1976; 38(3):807-10. [DOI:10.2466/pr0.1976.38.3.807]

- Colver A. Study protocol: SPARCLE-a multi-centre European study of the relationship of environment to participation and quality of life in children with cerebral palsy. BMC Public Health. 2006; 6(1):105. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-6-105] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Riahi A, Rassafiani M, Binesh M. The cross-cultural validation and test-retest and inter-rater reliability of the Persian translation of parent version of the Gross Motor Function Classification System for children with Cerebral Palsy. Journal of rehabilitation. 2013; 13(5):25-30.

- Riyahi A, Rassafiani M, AkbarFahimi N, Sahaf R, Yazdani F. Cross-cultural validation of the Persian version of the Manual Ability Classification System for children with cerebral palsy. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation. 2013; 20(1):19-24. [DOI:10.12968/ijtr.2013.20.1.19]

- Olawale OA, Deih AN, Yaadar RK. Psychological impact of cerebral palsy on families: The African perspective. Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice. 2013; 4(2):159-63. [DOI:10.4103/0976-3147.112752] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Thomasgard M, Metz WP. Parental overprotection and its relation to perceived child vulnerability. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1997; 67(2):330-5. [DOI:10.1037/h0080237] [PMID]

- Segrin C, Woszidlo A, Givertz M, Montgomery N. Parent and child traits associated with overparenting. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2013; 32(6):569-95. [DOI:10.1521/jscp.2013.32.6.569]

Article type: Original Research Articles |

Subject:

methodology in rehabilitation

Received: 2018/11/28 | Accepted: 2019/07/3 | Published: 2019/12/29

Received: 2018/11/28 | Accepted: 2019/07/3 | Published: 2019/12/29

Send email to the article author