BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1040-en.html

2- Occupational Therapy, Rehabilitation Faculty, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

1. Introduction

ancer is one of the 4 major causes of mortality among children. Childhood cancers are rare and only encompass about 1% of new cases of cancer in the United States. Tumors of hematopoietic stem cells (leukemia and lymphoma) are the most common ones, and tumors of the central nervous system, soft tissues, and bone sarcomas, respectively, occupy the other ranks. The survival rate for children under 14 years has dramatically increased since the 1960s so that 5-year and 3-year survival rates reached from 28% to 75% and 80%, respectively, in the 1990s [1].

Cancer is not a simple disease, but a complex sequence of events. Children diagnosed with cancer experience various stages of treatment, potential periods of remission, and recurrence of the same pathology and symptoms. The multiple stages are different depending on the type, affected area, severity, and progression of the disease and are usually accompanied by multiple and prolonged hospitalization. Hospitalized children have special needs that should be addressed according to their conditions.

Cancer detection and its related treatments (eg chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and operation) impose unwanted physical (eg pain, fatigue, peripheral neuropathy, and hair loss) and psychological (eg anxiety, depression, and irritability) complications for children and their families [2]. Furthermore, the process of numerous and sometimes long-lasting hospitalizations exacerbates the conditions in a way that it makes children face with the limitations and problems in doing their daily activities (eg self-care, play, social participation, and educational activities). It will eventually be associated with reducing the quality of life of children. In these conditions, interventions of occupational therapy are required for maintaining or restoring children’s abilities to perform activities of daily living and enhance the quality of life [3].

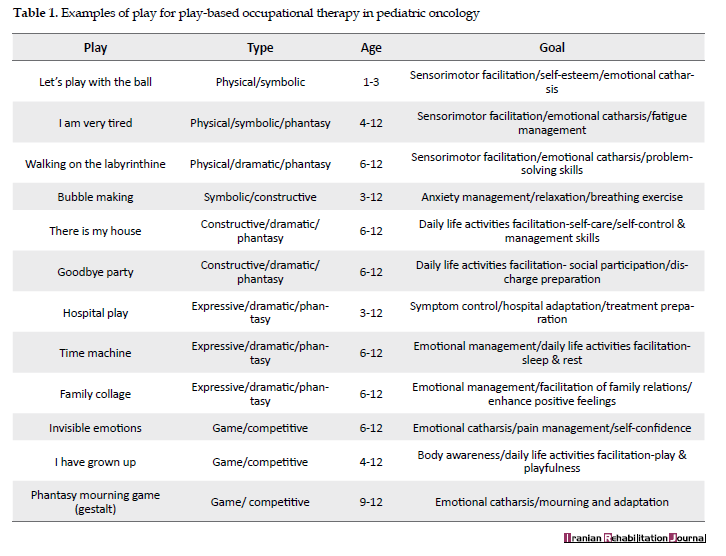

Unfortunately, because of the special complications of pediatric oncology, difficulties of service delivery, and lack of frameworks and guidelines for occupational therapy, a minority of therapists are encouraged to work in such wards and leads to reduce the level of health care delivery and services (especially rehabilitation) in the pediatric cancer population. For this purpose, we try to formulate the stages of occupational therapy service in pediatric oncology and palliative care, based on “play-based occupational therapy”, to facilitate the delivery of rehabilitation care services (Table 1).

2. Play in occupational therapy

Play is the child’s world. Given that play is the most important childhood activity, occupational therapists can make the process of evaluation and treatment of these children through play. They can control the intervention process including “play as means” and “play as an end”. As a means, the play includes the usage of it to facilitate daily activities of a child’s life (training skills) or control and manage psychological symptoms [4]. Occupational therapists also can take advantage of play as an end. As an end, any intervention applied to facilitate the process of playing and playfulness in different situations (home, school, and hospital) involves in this part. The limitation of a child’s play can affect all other aspects of life, as well as his disease and treatment. This limitation can be because of the disease and the complications of treatment or hospitalization. The therapist can minimize limitations and remove barriers by facilitating the process of play and creating conditions to do playful activities [5, 6].

3. Occupational therapy in pediatric oncology

Whether the therapist uses play as a means or as an end, occupational therapy intervention process in hospitalized children with cancer includes the following stages:

Evaluation process

Child evaluation: it includes the evaluation of developmental status, play (including play history, interests, priorities, and needs of a child’s play), participation in daily life activities, quality of life, and the evaluation of physical and psychological symptoms (such as pain, fatigue, and anxiety).

Environment evaluation: it includes the child’s living environment (home), the hospital, and the school environment.

Caregivers evaluation: it includes parents, staff, etc.

Intervention process

After evaluating and gathering necessary information, the therapist must act for setting goals and planning the interventions. Concerning cancer diagnosis, treatment received and hospitalization, the most important therapeutic goals, could include:

Controlling or reducing physical and psychological symptoms affecting participation and quality of life of children.

Facilitating the skills needed for independent doing of everyday activities in the hospital.

Applying environmental changes necessary to facilitate participation in activities.

Preparing the child and family to continue doing activities at home or school after the hospital discharge [7-10].

4. Re-evaluation, discharge planning, and follow-up

Play-based occupational therapy is a dynamic process. A re-evaluation must be carried out through the whole intervention process. This phase summarizes the change in the child’s ability to engage in activities of daily life between the initial evaluation and hospital discharge and make a recommendation as possible.

5. Play-based occupational therapy in oncology

Predetermined objectives can be achieved by planning interventions through play. The play-based occupational therapy process begins with taking the play history of the child. Children’s play history that includes past and present children’s play experiences (including emphasis, material, action, people, and setting) can specify the interests, priorities, and needs of the child’s play. The first step of treatment planning is collecting the information in a semi-structured interview with parents. By combining the results of the interview with other evaluations, which includes the choice of play, the planning will be carried out. Like any other selective plays, any activities used in occupational therapy should be purposeful, meaningful and of interest to children.

Given that playful interventions are selected among child’s play experiences of the past and present, they usually have these characteristics. Besides, the therapist should consider the point that the selected plays should have flexibility in terms of intervention so that it could be shunted for certain purposes or be floated among different objectives. It is worth noting that in selecting the plays, age-appropriateness, presence of play-room (or bed-bound child), and certain circumstances of the hospital environment should be considered in the way that, if necessary, changes in the play or the environment could be exercised. [5, 11-13].

After selecting the play activities, the implementation of the process of play-based occupational therapy will run. Unlike play therapy, which generally uses a direct or indirect approach, play-based therapy uses a selective approach, which means that it is flexible concerning the conditions of children, the environment, and play, and fluctuates between direct and indirect approaches. For example, for a child, who has poor cooperation and does not participate in the play, it may be required to use a direct approach at the beginning of the intervention; then, along with the child’s progress, an indirect approach may be replaced.

In addition to familiarity with various approaches to play, the occupational therapist must combine the functionality and proper use of each of these approaches in its own right. The therapist may take a different role in each stage of the process (from guiding the process to following the child), which should be done purposefully and to achieve therapeutic purposes. However, this change of roles should not be carried out in the way that the child realizes it or interferes in the process of treatment [14-16].

The final stage, which is usually done at the same time or before hospital discharge, is the re-evaluation of the program and determination of the goals attainment rate. However, this does not mean that the therapist should not evaluate the process, but because of the dynamic and flexible nature of play-based occupational therapy, the evaluation should be performed at each stage and changes and improvements should be considered in the program. In the end, necessary training is given to the child and caregivers so that the process continues at home if it is required [7].

6. Conclusion

Early occupational therapy access in pediatric oncology can improve participation in daily life, quality of life, and symptom control and probably reduce the cost of care. The complications of pediatric oncology often prevent occupational therapists from entering this area (especially for hospitalized children), which leads to reducing the quantity and quality of services. Also, using play as a guideline for occupational therapy interventions and introducing it as a rehabilitation process to other team members, children, and caregivers is important. It can reduce distresses of the diagnosis of cancer, unpleasant treatments, and long-term hospitalization in children and their families.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles were considered in this article.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed in designing, running, and writing all parts of the research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Marcdante KJ, Kliegman R. Nelson essentials of pediatrics. 7th edition. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2015.

- O’Dell M, Stubblefield M. Cancer rehabilitation: Principles and practice. New York: Demos Medical Publishing; 2009.

- Rankin J, Robb K, Murtagh N, Cooper J, Lewis S. Rehabilitation in cancer care. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008.

- Diane Parham L, Fazio LS. Play in occupational therapy for children. 2nd edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2008. [DOI:1016/B978-0-323-02954-4.X0001-3]

- Webb J. Play therapy with hospitalized children. International Journal of Play Therapy. 1995; 4(1):51-9. [DOI:10.1037/h0089214]

- Koukourikos K, Tzeha L, Pantelidou P, Tsaloglidou A. The importance of play during hospitalization of children. Materia Socio-Medica. 2015; 27(6):538-441. [DOI:10.5455/msm.2015.27.438-441] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Cooper J, editor. Occupational therapy in oncology and palliative care. 2nd edition. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2006.

- Penfold SL. The role of occupational therapy in oncology. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 1996; 22(1):75-81. [DOI:10.1016/S0305-7372(96)90016-X]

- Sleight AG, Stein Duker LI. Toward a broader role for occupational therapy in supportive oncology care. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2016; 70(4):7004360030. [DOI:10.5014/ajot.2016.018101] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Lo JL, Chi PY, Chu HH, Wang HY, Chou SCT. Pervasive computing in play-based occupational therapy for children. IEEE Pervasive Computing. 2009; 8(3):66-73. [DOI:10.1109/MPRV.2009.52]

- Okimoto AM, Bundy A, Hanzlik J. Playfulness in children with and without disability: Measurement and intervention. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2000; 54:73-82. [DOI:10.5014/ajot.54.1.73] [PMID]

- Rodger S, Zivviani J. Play-based occupational therapy. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education. 1999; 46(3):337-65. [DOI:10.1080/103491299100542]

- Longpré Sh, Newman R. Occupational therapy’s role with oncology [Internet]. 2011 [Updated 2011]. Available from: https://www.aota.org/~/media/Corporate/Files/AboutOT/Professionals/WhatIsOT/RDP/Facts/Oncology%20fact%20sheet.pdf

- Webb NB, editor. Play therapy with children in crisis. 3rd edition. New York: Guilford Publications; 2007.

- Cordier R, Bundy A, Hocking C, Einfeld S. A model for play-based intervention for children with ADHD. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2009; 56(5):332-40. [DOI:10.1111/j.1440-1630.2009.00796.x] [PMID]

- Solanki PV, Gokhale P, Agarwal P. To study the effectiveness of play based therapy on play behaviour of children with Down’s syndrome. Indian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2014; 46(2):41-8.

Received: 2019/07/3 | Accepted: 2019/09/23 | Published: 2020/03/1