Volume 22, Issue 1 (March 2024)

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2024, 22(1): 25-34 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ashori M, Rashidi B. Predicting Psychological Well-being Based on Psychosocial Factors in Deaf and Hard-of-hearing Adolescents. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2024; 22 (1) :25-34

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1824-en.html

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1824-en.html

1- Department of Psychology and Education of People with Special Needs, Faculty of Education and Psychology, University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 507 kb]

(1064 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3577 Views)

Full-Text: (650 Views)

Introduction

Adolescence is a time of rapid changes in cognitive, physical, social, and emotional development. Adolescents must acclimate to developing environmental pressures and adapt to growing needs and skills [1]. These rapid changes can lead to the emergence of various stressors that affect the well-being of adolescents [2]. The deaf and hard-of-hearing (DHH) child or adolescent in a family may affect all family members [3]. Deafness puts a person in a difficult place [4], while relationships with family members and DHH peers provide endless opportunities to learn how to resolve interpersonal, emotional, and social problems [5].

Although DHH students can use sign or spoken language, hearing loss affects their learning capacity [6]. Moreover, adolescence is a critical period of development characterized by significant physical, cognitive, emotional, and social growth [7]. Changes in this period, in addition to challenging school requirements, increasing peer interactions, and evolving communication patterns with friends and family members, may expose adolescents to undesirable experiences and challenge their abilities [8]. The relationship between quality of life (QoL) and psychological stress has been the focus of much research. Anxiety, depression, and stress are very common and often associated with general health problems that often occur in adolescence [9].

Cognitive vulnerability-stress theory on the development of depression hypothesizes that when adolescents experience negative life events, negative patterns of thinking play a critical role in depressive symptoms [10]. Stress is one of the factors that negatively affect an individual’s well-being and QoL [11]. When an adolescent cannot cope with stressful life events, the symptoms of depression may increase [12]. In addition, there is a wide range of anxiety disorders. For this reason, various theoretical models try to explain the causes of these problems. However, models of anxiety disorders suggest that perceived threats and stressful events lead to symptoms of anxiety through overly cognitive distortions and frightening biases [13]. Anxiety and stress also explain a large percentage of depressive symptoms in adolescents [9]. Some evidence suggests that increased stressors are a potential threat to adolescents’ well-being and QoL [11].

Well-being is associated with positive career, health, and social outcomes in life [14]. QoL is closely related to public health [15]. Many factors affect and contribute to a person’s QoL which refers to a person’s perceived mental and physical well-being [16]. QoL includes well-being, health, satisfaction with daily living, and social participation [17]. Health-related QoL can be affected by disease and treatment and is related to factors that affect people’s QoL [16]. Sensory impairments such as hearing loss can affect the QoL [17]. Numerous studies have revealed that DHH people have poorer social and physical functioning, QoL, and mental health [18-20]. The QoL and well-being of these people need to be addressed. However, few studies have predicted psychological well-being based on psychosocial factors in DHH adolescents.

Wiseman et al. revealed that the temperament of DHH students significantly predicted stress in parents [21]. A study by Adibsereshki et al. showed that well-being and happiness were closely related to coping strategies in deaf adolescents [22]. Adigun stated that self-efficacy and self-esteem had a direct and positive relationship with intimate image diffusion among deaf adolescents [23]. Brice and Strauss concluded that QoL is associated with self-concept, identity development, and adjustment in deaf adolescents [1]. Kushalnagar et al. suggested that the QoL positively correlated with parent relations, but negatively related to perceived stigma and depression symptoms in DHH adolescents [24]. The findings of Fellinger et al. indicated that the general health and QoL associated with a type of hearing loss in DHH people [25]. Chia et al. suggested that psychosocial effects are associated with hearing loss. These effects include poorer mood and physical functioning, decreased well-being, social isolation, and depression [26].

DHH adolescents are faced with problems in managing emotion and behavior, where access to communication and information is incomplete at best [1]. Although there is an interest in studying the QoL in DHH adolescents [27], these adolescents face more problems than hearing peers [28]. Previous research on psychological well-being and QoL emphasizes the relationship between stress, anxiety, and depression. However, the high degree of coexistence between these problems has led experts to predict psychological well-being based on QoL, health, stress, anxiety, and depression.

DHH adolescents are more at risk for health problems, stress, anxiety, and depression than hearing adolescents. On the other hand, there was some research available on the role of health, QoL, depression, anxiety, and stress on psychological well-being in these adolescents. In addition, there is some research on the relationship between QoL, health, depression, anxiety, stress, and psychological well-being among DHH adolescents. Therefore, this study aimed to predict psychological well-being based on psychosocial factors in DHH adolescents.

Materials and Methods

One hundred and twenty DHH adolescents who were in sixth and twelfth grades were selected by convenient sampling from secondary schools for the deaf in Isfahan City, Iran. Originally, 62 people were in the age range of 11 to 14 years and 58 people were in the age range of 15 to 19 years. Based on the academic records, participants ranged in IQ from 91 to 103 with a Mean±SD of 96.01±0.34. The inclusion criteria included sensorineural DHH>36 decibels (dB). These participants had hearing aids before the age of five. Additional criteria included an age range between 11 and 19 years with a Mean±SD of 15.92±0.38 (male 45%; female 55%), living with parents, speaking Persian as a first language, studying in deaf schools from seventh to twelfth grade, having no disorders such as cerebral palsy or autism, and being able to complete questionnaires. The exclusion criteria for subjects were neurological and psychological disorders.

The health-related QoL questionnaire (KIDSCREEN-27) was used for assessing the health-related QoL (HRQOL) of the participants. This questionnaire was designed by Robitail et al. [29] and includes 27 items assessing five subscales of HRQOL, which are physical well-being (5 items), psychological well-being (7 items), school environment (4 items), peers and social support (4 items), and parent relations and autonomy (7 items). The KIDSCREEN-27 is scored from “1” to “5”, meaning never and always, respectively. The score of the subscales is linearly converted from 0 to 100, and 100 indicates the best QoL. The reliability of the psychological well-being, physical well-being, school environment, social support and peers, and parent relations and autonomy subscales assessed through the Cronbach’s α was between 0.78 and 0.84. Its correlation with KIDSCREEN-52 has been reported in the range of 0.63 to 0.96 [29]. In Iran, Nik-Azin et al. reported the reliability for the subscales of the KIDSCREEN-27 through the Cronbach’s α between 0.64 and 0.84, and its validity from 0.42 to 0.73. The test re-test correlations ranged from 0.52 to 0.78 [30].

The youth QoL instrument-deaf and hard of hearing (YQOL-DHH) was used for evaluating the QoL of the participants. The YQOL-DHH was designed by Patrick et al. for DHH adolescents. It includes 32 questions evaluating three subscales of QoL, which are self-advocacy/acceptance (14 questions), participation (10 questions), and perceived stigma (8 questions). Each question is graded from “0” to “10”, and respectively means not at all to very much. Given that each of the subscales of self-advocacy/acceptance, participation, and perceived stigma have 14, 10, and 8 questions, the minimum and maximum scores for each subscale are 14 to 140, 10 to 100, and 8 to 80, respectively [31]. This questionnaire does not have a total score. In addition, a higher score on the self-advocacy/acceptance and participation subscales, and a lower score on the perceived stigma subscale indicate a higher QoL [32]. The reliability of the self-advocacy/acceptance, participation, and perceived stigma subscales estimated by test re-test coefficients, was 0.70, 0.92, and 0.78, respectively. The Cronbach’s α reliability for subscales were 0.84, 0.86, and 0.85, respectively. The validity of the subscales was between 0.28 and 0.70 [31]. In the current study, the content validity index for subscales was 0.79, 0.85, and 0.88, respectively. The reliability of the self-advocacy/acceptance, participation, and perceived stigma subscales estimated by Cronbach’s α was 0.84, 0.83, and 0.81, respectively. The reliability of the subscales using the test re-test coefficients also was 0.76, 0.74, and 0.73, respectively.

The depression, anxiety, and stress scale-21 (DASS-21) were used for assessing the depression, anxiety, and stress of the participants. This questionnaire was developed by Lovibond and Lovibond and includes 21 items assessing three subscales, which are depression, anxiety, and stress. Each subscale has seven items. The DASS-21 is rated from “0” (not at all) to “3” (too high) [33]. The final score of each subscale is obtained through the sum of the scores of the related items. Scores on the DASS-21 will need to be multiplied by 2 to calculate the final score. Therefore, the minimum and maximum scores for each subscale are between 0 and 42. Higher scores are associated with higher stress, anxiety, and depression [34]. The reliability of the stress, anxiety, and depression subscales estimated by the Cronbach’s α was 0.95, 0.92, and 0.97, respectively. Also, a correlation of 0.48 was found between stress and depression, 0.53 between stress and anxiety, and 0.28 between depression and anxiety [35]. In Iran, Samani and Jokar estimated the validity coefficients for DASS-21 at 0.90. The reliability coefficients by test re-test for stress, anxiety, and depression were 0.77, 0.76, and 80, respectively [36].

The participants became aware of the aim of this study, using sign language or total communication. We divided the subjects into small groups and then told them how to fill out the questionnaires. Thus, DHH adolescents filled out the KIDSCREEN-27, YQOL-DHH, and DASS-21 in their classrooms. Completion of these questionnaires took about 20 to 25 minutes. Data obtained by the KIDSCREEN-27, YQOL-DHH, and DASS-21 were analyzed by stepwise regression and Pearson correlation methods. Correlation was run to explore the relationships among data. Then, the stepwise regression was performed to predict psychological well-being based on QoL, health, stress, anxiety, and depression in DHH adolescents.

Results

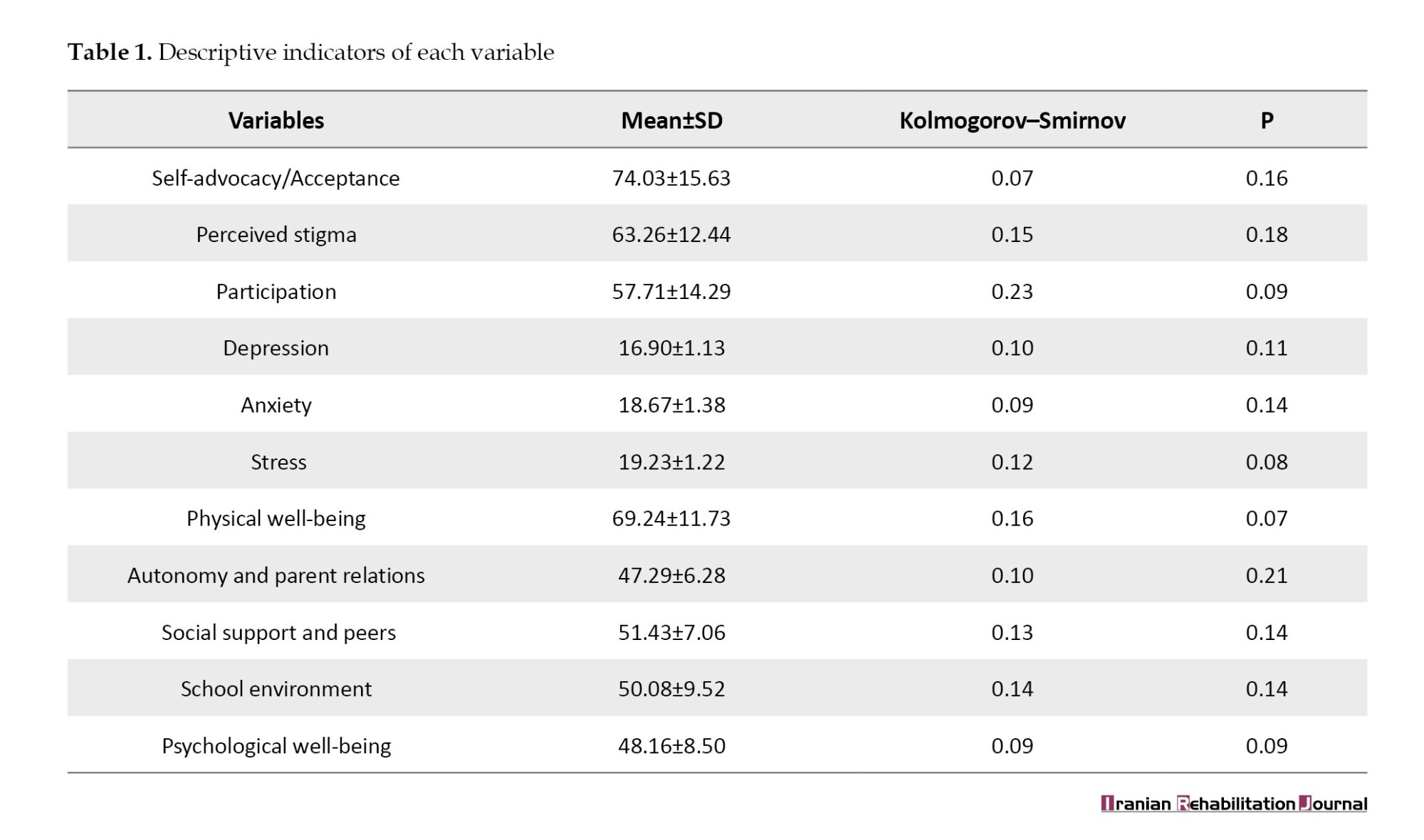

The descriptive statistics for the subscales of KIDSCREEN-27 (psychological well-being, physical well-being, school environment, social support and peers, and autonomy and parent relations), YQOL-DHH (self-advocacy/acceptance, perceived stigma, and participation), and DASS-21 (depression, anxiety, and stress) are reported in Table 1.

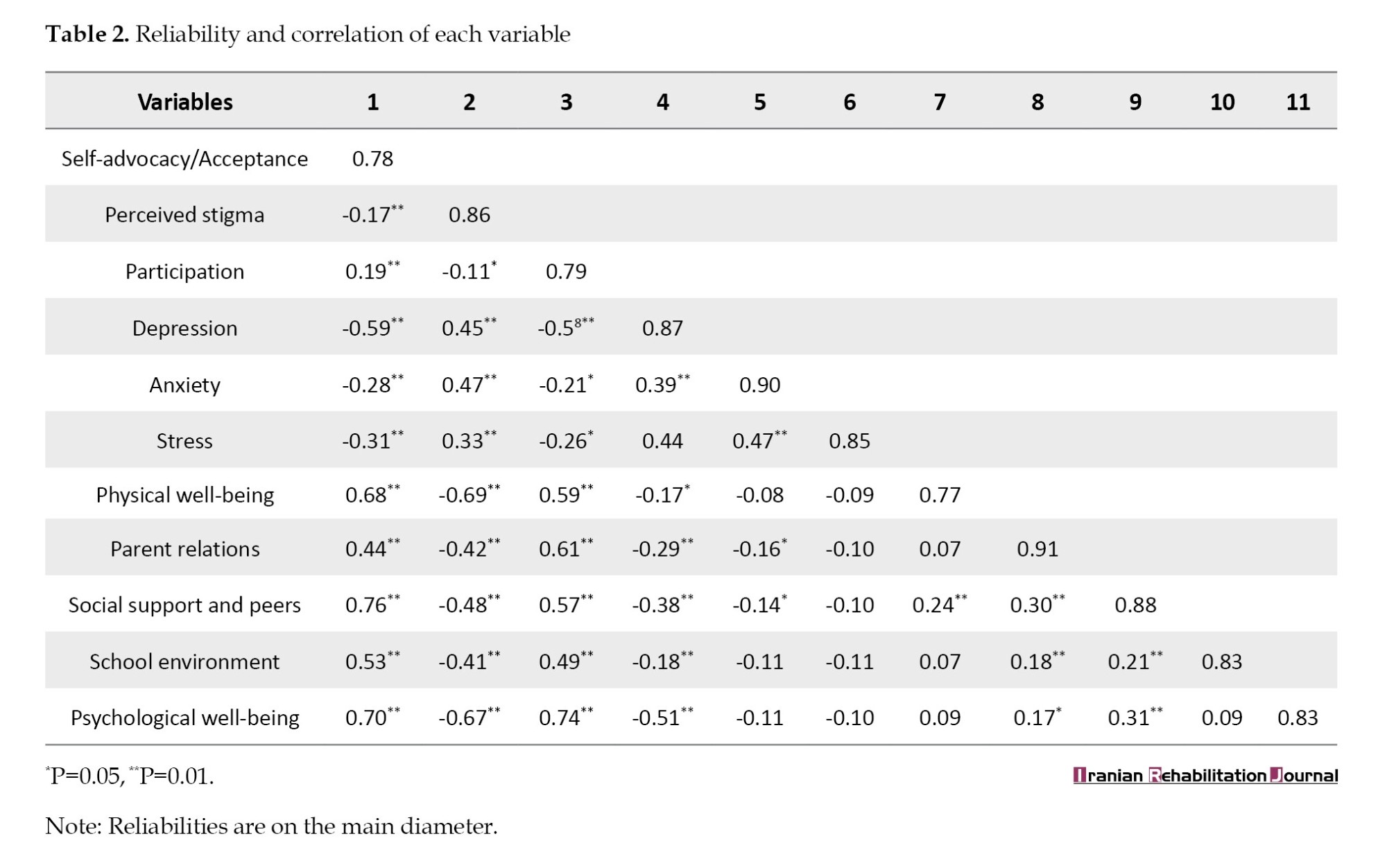

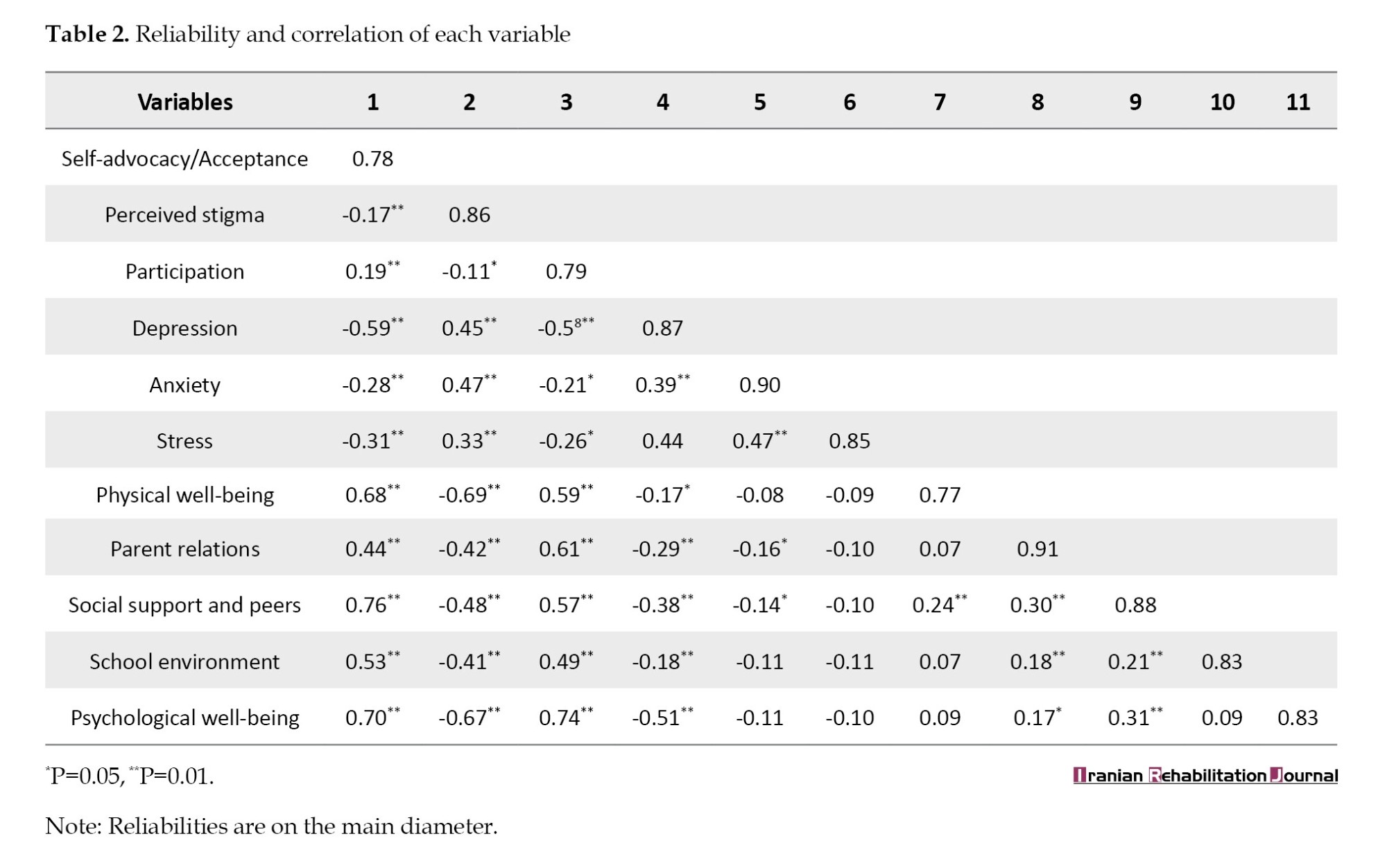

The descriptive indicators of variables are reported in Table 1. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test approved the normality of the distribution of scores (P>0.05). The correlations between self-advocacy/acceptance, participation, perceived stigma, stress, anxiety, depression, social support and peers, physical well-being, school environment, parent relations and autonomy, and psychological well-being are demonstrated in Table 2.

According to Table 2, psychological well-being positively correlated with self-advocacy/acceptance (r=0.70, P<0.01), participation (r=0.74, P<0.01), parent relations (r=0.17, P<0.05), and social support (r=0.31, P<0.01), but negatively correlated with perceived stigma (r=-0.67, P<0.01) and depression (r=-0.51, P<0.01). Psychological well-being had no significant association with anxiety, stress, physical well-being, and school environment stigma (P<0.01).

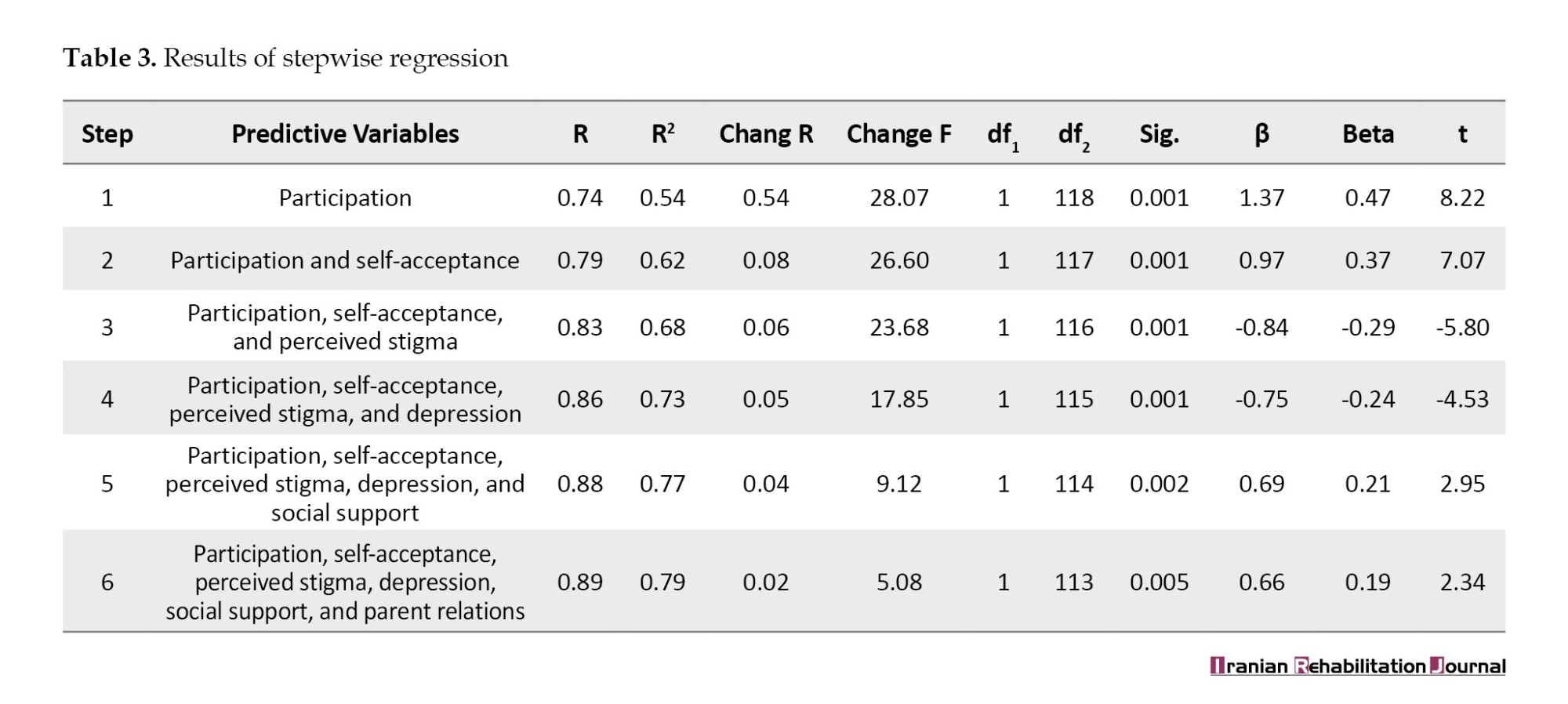

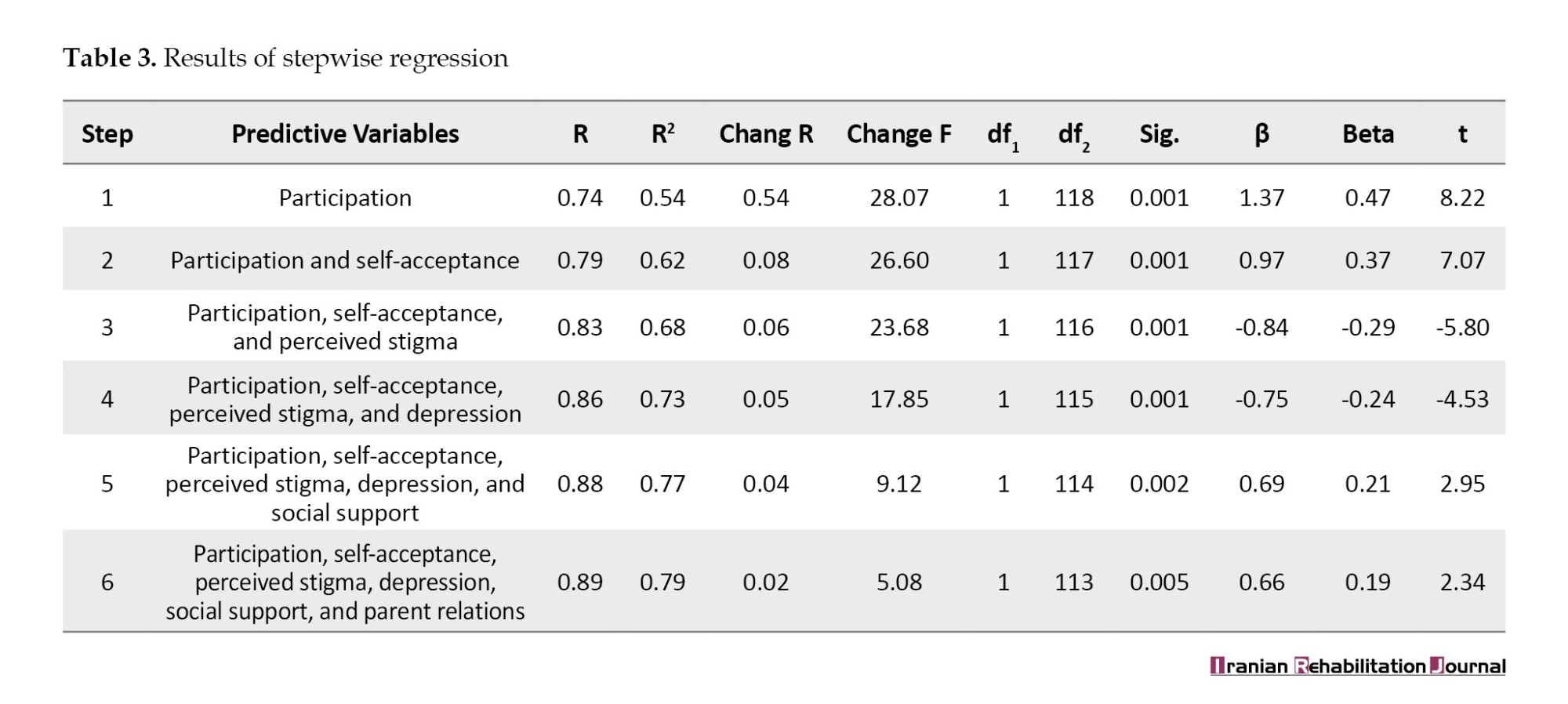

To predict DHH adolescents’ psychological well-being, a stepwise regression was run. Independent error hypothesis was tested by ensuring that the Durbin-Watson was >1 and <3 [37]. Because its value was equal to 1.81, it was approved. The hypothesis of multicollinearity was tested by confirming that no predictor correlated >±0.8, a tolerance statistic >0.1, and a variance inflation factor statistic (VIF) <10 [38]. Because the tolerance statistic was close to 1 and the VIF was <2, stepwise regression analysis was used, the results of which are reported in Table 3.

As reported in Table 3, in the first phase, participation had the largest share in predicting psychological well-being. It could be explained by 54% of the variation in psychological well-being (β=1.37, t=8.22, P<0.001). In the second phase, after participation, self-advocacy/acceptance was entered into the analysis and these two variables explained 79% of the variation in psychological well-being (β=0.97, t=7.07, P<0.001). In the third phase, besides participation and self-advocacy/acceptance, perceived stigma entered into the analysis and these variables predicted 83% of the variation in psychological well-being (β=-0.84, t=5.80, P<0.001). In the last two phases, depression and social support entered the analysis and predicted 86 and 88% of the variation in psychological well-being, respectively (β=0.75, t=4.53, P<0.001; β=0.69, t=2.95, P<0.002). In the sixth phase, parent relations entered the regression and these variables predicted 89% of the change in psychological well-being (β=0.66, t=2.34, P<0.005).

Discussion

The current research predicted psychological well-being based on psychosocial factors in DHH adolescents. The results suggested that self-advocacy/acceptance, participation, social support, and parent relations had a significant and positive relationship with psychological well-being. Also, perceived stigma and depression had a significant and negative relationship with psychological well-being. In the predictive model, participation, perceived stigma, self-advocacy/acceptance, depression, social support, and parent relations explained the psychological well-being of the participants. Participation also had the most important and the greatest role.

The results were similar to Wiseman et al. who reported the temperament of DHH students significantly predicted stress in parents [21]. The result was consistent with Adigun, who revealed that self-efficacy and self-esteem had a direct and positive relationship with intimate image diffusion among DHH adolescents [23]. The findings were similar to Adibsereshki et al. who indicated that well-being and happiness were closely related to coping strategies in DHH adolescents [22]. Brice and Strauss found that QoL is associated with self-concept, identity development, and adjustment in DHH adolescents [1]. Fellinger et al. revealed the QoL and mental health was consistent with a type of hearing loss in DHH students [25]. Furthermore, the result associated with Chia et al. suggesting that well-being was closely related to QoL, physical functioning, social isolation, and depression [26].

To explain this finding, it can be said that DHH people are more vulnerable to psychological well-being than their hearing people in terms of psychological problems and mental health [28]. There is a positive relationship between self-acceptance and psychological well-being in DHH students [39]. Therefore, better self-advocacy/acceptance is associated with higher psychological well-being.

One of the important effects of hearing loss is on a person’s capability to communicate with peers and parents. Exclusion from communication can have a primary effect on daily life, causing loneliness, isolation, and feelings of frustration, especially among DHH adolescents [40]. The QoL among DHH adolescents is related to their communication with their parents [41]. The QoL positively correlated with the parent relations, but negatively related to perceived stigma and depression symptoms in DHH adolescents [24]. Previous studies suggested the importance of communication between DHH adolescents and their parents [4, 24, 42]. In other words, the QoL of DHH adolescents varies with the degree to which they relate to their parents. As the level of relationships with parents increases, the QoL also increases significantly [43]. Hearing loss can affect adolescents’ ability to develop communication and social skills. The sooner DHH adolescents begin receiving services, the more likely they are to reach their total capacity.

Although the findings of the current study explain more precisely the well-being of DHH students, there are some limitations. First, as seen in studies of DHH people, the participants were heterogeneous in their use of different educational methods, communication approaches, cause of hearing loss, and duration of use of hearing aids. These variables may affect the well-being of subjects. Additionally, only DHH adolescents whose reading skills allowed them to complete the questionnaires participated in this study.

The critical strength of this research was the participation of DHH adolescents aged 11–19 years. These results have clinical and educational implications for those psychologists working with DHH adolescents regarding the importance of QoL, health, depression, anxiety, stress, and psychological well-being during the challenging stage of adolescence. Other psychologists could choose a larger sample size. It is recommended to study the psychological well-being of DHH adolescents in clinical and educational environments based on gender and age; It is also suggested to examine the relationship between social skills and self-esteem with the psychological well-being of DHH people.

Technology-based interventions have been applied in Iran to improve mental health and QoL among some population groups. Similar technology-based interventions need to be assessed and applied to DHH adolescents in Iran. Randomized controlled trials need to be designed to evaluate how technology-based interventions can reduce stress and depression among DHH adolescents.

Conclusion

Psychological well-being is considered a combination of positive emotional states and optimal performance in individual and social life. Psychological well-being positively correlated with the QoL, but negatively correlated with psychological distress in DHH adolescents. DHH adolescents may also struggle with various psychological distress. Indeed, the QoL, health, depression, anxiety, and stress in these adolescents can affect their psychological well-being.

This study predicted psychological well-being based on psychosocial factors in DHH adolescents. The findings showed that the QoL, health, depression, anxiety, and stress were significant predictors of the psychological well-being of DHH adolescents. Then, these variables play an important contribution to the well-being of deaf individuals. The results of this study will further help researchers and psychologists reinforce psychotherapy interventions to enhance the components of psychological well-being, QoL, and psychological distress in DHH adolescents.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Human Ethics Research Committee of the University of Isfahan. Informed consent was obtained and the participants were informed that participating in the study was optional.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Mohammad Ashori; Performing the experiment: Bahar Rashidi; Data analysis and writhing the manuscript: Mohammad Ashori and Bahar Rashidi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all deaf adolescents who participated in this study.

References

Adolescence is a time of rapid changes in cognitive, physical, social, and emotional development. Adolescents must acclimate to developing environmental pressures and adapt to growing needs and skills [1]. These rapid changes can lead to the emergence of various stressors that affect the well-being of adolescents [2]. The deaf and hard-of-hearing (DHH) child or adolescent in a family may affect all family members [3]. Deafness puts a person in a difficult place [4], while relationships with family members and DHH peers provide endless opportunities to learn how to resolve interpersonal, emotional, and social problems [5].

Although DHH students can use sign or spoken language, hearing loss affects their learning capacity [6]. Moreover, adolescence is a critical period of development characterized by significant physical, cognitive, emotional, and social growth [7]. Changes in this period, in addition to challenging school requirements, increasing peer interactions, and evolving communication patterns with friends and family members, may expose adolescents to undesirable experiences and challenge their abilities [8]. The relationship between quality of life (QoL) and psychological stress has been the focus of much research. Anxiety, depression, and stress are very common and often associated with general health problems that often occur in adolescence [9].

Cognitive vulnerability-stress theory on the development of depression hypothesizes that when adolescents experience negative life events, negative patterns of thinking play a critical role in depressive symptoms [10]. Stress is one of the factors that negatively affect an individual’s well-being and QoL [11]. When an adolescent cannot cope with stressful life events, the symptoms of depression may increase [12]. In addition, there is a wide range of anxiety disorders. For this reason, various theoretical models try to explain the causes of these problems. However, models of anxiety disorders suggest that perceived threats and stressful events lead to symptoms of anxiety through overly cognitive distortions and frightening biases [13]. Anxiety and stress also explain a large percentage of depressive symptoms in adolescents [9]. Some evidence suggests that increased stressors are a potential threat to adolescents’ well-being and QoL [11].

Well-being is associated with positive career, health, and social outcomes in life [14]. QoL is closely related to public health [15]. Many factors affect and contribute to a person’s QoL which refers to a person’s perceived mental and physical well-being [16]. QoL includes well-being, health, satisfaction with daily living, and social participation [17]. Health-related QoL can be affected by disease and treatment and is related to factors that affect people’s QoL [16]. Sensory impairments such as hearing loss can affect the QoL [17]. Numerous studies have revealed that DHH people have poorer social and physical functioning, QoL, and mental health [18-20]. The QoL and well-being of these people need to be addressed. However, few studies have predicted psychological well-being based on psychosocial factors in DHH adolescents.

Wiseman et al. revealed that the temperament of DHH students significantly predicted stress in parents [21]. A study by Adibsereshki et al. showed that well-being and happiness were closely related to coping strategies in deaf adolescents [22]. Adigun stated that self-efficacy and self-esteem had a direct and positive relationship with intimate image diffusion among deaf adolescents [23]. Brice and Strauss concluded that QoL is associated with self-concept, identity development, and adjustment in deaf adolescents [1]. Kushalnagar et al. suggested that the QoL positively correlated with parent relations, but negatively related to perceived stigma and depression symptoms in DHH adolescents [24]. The findings of Fellinger et al. indicated that the general health and QoL associated with a type of hearing loss in DHH people [25]. Chia et al. suggested that psychosocial effects are associated with hearing loss. These effects include poorer mood and physical functioning, decreased well-being, social isolation, and depression [26].

DHH adolescents are faced with problems in managing emotion and behavior, where access to communication and information is incomplete at best [1]. Although there is an interest in studying the QoL in DHH adolescents [27], these adolescents face more problems than hearing peers [28]. Previous research on psychological well-being and QoL emphasizes the relationship between stress, anxiety, and depression. However, the high degree of coexistence between these problems has led experts to predict psychological well-being based on QoL, health, stress, anxiety, and depression.

DHH adolescents are more at risk for health problems, stress, anxiety, and depression than hearing adolescents. On the other hand, there was some research available on the role of health, QoL, depression, anxiety, and stress on psychological well-being in these adolescents. In addition, there is some research on the relationship between QoL, health, depression, anxiety, stress, and psychological well-being among DHH adolescents. Therefore, this study aimed to predict psychological well-being based on psychosocial factors in DHH adolescents.

Materials and Methods

One hundred and twenty DHH adolescents who were in sixth and twelfth grades were selected by convenient sampling from secondary schools for the deaf in Isfahan City, Iran. Originally, 62 people were in the age range of 11 to 14 years and 58 people were in the age range of 15 to 19 years. Based on the academic records, participants ranged in IQ from 91 to 103 with a Mean±SD of 96.01±0.34. The inclusion criteria included sensorineural DHH>36 decibels (dB). These participants had hearing aids before the age of five. Additional criteria included an age range between 11 and 19 years with a Mean±SD of 15.92±0.38 (male 45%; female 55%), living with parents, speaking Persian as a first language, studying in deaf schools from seventh to twelfth grade, having no disorders such as cerebral palsy or autism, and being able to complete questionnaires. The exclusion criteria for subjects were neurological and psychological disorders.

The health-related QoL questionnaire (KIDSCREEN-27) was used for assessing the health-related QoL (HRQOL) of the participants. This questionnaire was designed by Robitail et al. [29] and includes 27 items assessing five subscales of HRQOL, which are physical well-being (5 items), psychological well-being (7 items), school environment (4 items), peers and social support (4 items), and parent relations and autonomy (7 items). The KIDSCREEN-27 is scored from “1” to “5”, meaning never and always, respectively. The score of the subscales is linearly converted from 0 to 100, and 100 indicates the best QoL. The reliability of the psychological well-being, physical well-being, school environment, social support and peers, and parent relations and autonomy subscales assessed through the Cronbach’s α was between 0.78 and 0.84. Its correlation with KIDSCREEN-52 has been reported in the range of 0.63 to 0.96 [29]. In Iran, Nik-Azin et al. reported the reliability for the subscales of the KIDSCREEN-27 through the Cronbach’s α between 0.64 and 0.84, and its validity from 0.42 to 0.73. The test re-test correlations ranged from 0.52 to 0.78 [30].

The youth QoL instrument-deaf and hard of hearing (YQOL-DHH) was used for evaluating the QoL of the participants. The YQOL-DHH was designed by Patrick et al. for DHH adolescents. It includes 32 questions evaluating three subscales of QoL, which are self-advocacy/acceptance (14 questions), participation (10 questions), and perceived stigma (8 questions). Each question is graded from “0” to “10”, and respectively means not at all to very much. Given that each of the subscales of self-advocacy/acceptance, participation, and perceived stigma have 14, 10, and 8 questions, the minimum and maximum scores for each subscale are 14 to 140, 10 to 100, and 8 to 80, respectively [31]. This questionnaire does not have a total score. In addition, a higher score on the self-advocacy/acceptance and participation subscales, and a lower score on the perceived stigma subscale indicate a higher QoL [32]. The reliability of the self-advocacy/acceptance, participation, and perceived stigma subscales estimated by test re-test coefficients, was 0.70, 0.92, and 0.78, respectively. The Cronbach’s α reliability for subscales were 0.84, 0.86, and 0.85, respectively. The validity of the subscales was between 0.28 and 0.70 [31]. In the current study, the content validity index for subscales was 0.79, 0.85, and 0.88, respectively. The reliability of the self-advocacy/acceptance, participation, and perceived stigma subscales estimated by Cronbach’s α was 0.84, 0.83, and 0.81, respectively. The reliability of the subscales using the test re-test coefficients also was 0.76, 0.74, and 0.73, respectively.

The depression, anxiety, and stress scale-21 (DASS-21) were used for assessing the depression, anxiety, and stress of the participants. This questionnaire was developed by Lovibond and Lovibond and includes 21 items assessing three subscales, which are depression, anxiety, and stress. Each subscale has seven items. The DASS-21 is rated from “0” (not at all) to “3” (too high) [33]. The final score of each subscale is obtained through the sum of the scores of the related items. Scores on the DASS-21 will need to be multiplied by 2 to calculate the final score. Therefore, the minimum and maximum scores for each subscale are between 0 and 42. Higher scores are associated with higher stress, anxiety, and depression [34]. The reliability of the stress, anxiety, and depression subscales estimated by the Cronbach’s α was 0.95, 0.92, and 0.97, respectively. Also, a correlation of 0.48 was found between stress and depression, 0.53 between stress and anxiety, and 0.28 between depression and anxiety [35]. In Iran, Samani and Jokar estimated the validity coefficients for DASS-21 at 0.90. The reliability coefficients by test re-test for stress, anxiety, and depression were 0.77, 0.76, and 80, respectively [36].

The participants became aware of the aim of this study, using sign language or total communication. We divided the subjects into small groups and then told them how to fill out the questionnaires. Thus, DHH adolescents filled out the KIDSCREEN-27, YQOL-DHH, and DASS-21 in their classrooms. Completion of these questionnaires took about 20 to 25 minutes. Data obtained by the KIDSCREEN-27, YQOL-DHH, and DASS-21 were analyzed by stepwise regression and Pearson correlation methods. Correlation was run to explore the relationships among data. Then, the stepwise regression was performed to predict psychological well-being based on QoL, health, stress, anxiety, and depression in DHH adolescents.

Results

The descriptive statistics for the subscales of KIDSCREEN-27 (psychological well-being, physical well-being, school environment, social support and peers, and autonomy and parent relations), YQOL-DHH (self-advocacy/acceptance, perceived stigma, and participation), and DASS-21 (depression, anxiety, and stress) are reported in Table 1.

The descriptive indicators of variables are reported in Table 1. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test approved the normality of the distribution of scores (P>0.05). The correlations between self-advocacy/acceptance, participation, perceived stigma, stress, anxiety, depression, social support and peers, physical well-being, school environment, parent relations and autonomy, and psychological well-being are demonstrated in Table 2.

According to Table 2, psychological well-being positively correlated with self-advocacy/acceptance (r=0.70, P<0.01), participation (r=0.74, P<0.01), parent relations (r=0.17, P<0.05), and social support (r=0.31, P<0.01), but negatively correlated with perceived stigma (r=-0.67, P<0.01) and depression (r=-0.51, P<0.01). Psychological well-being had no significant association with anxiety, stress, physical well-being, and school environment stigma (P<0.01).

To predict DHH adolescents’ psychological well-being, a stepwise regression was run. Independent error hypothesis was tested by ensuring that the Durbin-Watson was >1 and <3 [37]. Because its value was equal to 1.81, it was approved. The hypothesis of multicollinearity was tested by confirming that no predictor correlated >±0.8, a tolerance statistic >0.1, and a variance inflation factor statistic (VIF) <10 [38]. Because the tolerance statistic was close to 1 and the VIF was <2, stepwise regression analysis was used, the results of which are reported in Table 3.

As reported in Table 3, in the first phase, participation had the largest share in predicting psychological well-being. It could be explained by 54% of the variation in psychological well-being (β=1.37, t=8.22, P<0.001). In the second phase, after participation, self-advocacy/acceptance was entered into the analysis and these two variables explained 79% of the variation in psychological well-being (β=0.97, t=7.07, P<0.001). In the third phase, besides participation and self-advocacy/acceptance, perceived stigma entered into the analysis and these variables predicted 83% of the variation in psychological well-being (β=-0.84, t=5.80, P<0.001). In the last two phases, depression and social support entered the analysis and predicted 86 and 88% of the variation in psychological well-being, respectively (β=0.75, t=4.53, P<0.001; β=0.69, t=2.95, P<0.002). In the sixth phase, parent relations entered the regression and these variables predicted 89% of the change in psychological well-being (β=0.66, t=2.34, P<0.005).

Discussion

The current research predicted psychological well-being based on psychosocial factors in DHH adolescents. The results suggested that self-advocacy/acceptance, participation, social support, and parent relations had a significant and positive relationship with psychological well-being. Also, perceived stigma and depression had a significant and negative relationship with psychological well-being. In the predictive model, participation, perceived stigma, self-advocacy/acceptance, depression, social support, and parent relations explained the psychological well-being of the participants. Participation also had the most important and the greatest role.

The results were similar to Wiseman et al. who reported the temperament of DHH students significantly predicted stress in parents [21]. The result was consistent with Adigun, who revealed that self-efficacy and self-esteem had a direct and positive relationship with intimate image diffusion among DHH adolescents [23]. The findings were similar to Adibsereshki et al. who indicated that well-being and happiness were closely related to coping strategies in DHH adolescents [22]. Brice and Strauss found that QoL is associated with self-concept, identity development, and adjustment in DHH adolescents [1]. Fellinger et al. revealed the QoL and mental health was consistent with a type of hearing loss in DHH students [25]. Furthermore, the result associated with Chia et al. suggesting that well-being was closely related to QoL, physical functioning, social isolation, and depression [26].

To explain this finding, it can be said that DHH people are more vulnerable to psychological well-being than their hearing people in terms of psychological problems and mental health [28]. There is a positive relationship between self-acceptance and psychological well-being in DHH students [39]. Therefore, better self-advocacy/acceptance is associated with higher psychological well-being.

One of the important effects of hearing loss is on a person’s capability to communicate with peers and parents. Exclusion from communication can have a primary effect on daily life, causing loneliness, isolation, and feelings of frustration, especially among DHH adolescents [40]. The QoL among DHH adolescents is related to their communication with their parents [41]. The QoL positively correlated with the parent relations, but negatively related to perceived stigma and depression symptoms in DHH adolescents [24]. Previous studies suggested the importance of communication between DHH adolescents and their parents [4, 24, 42]. In other words, the QoL of DHH adolescents varies with the degree to which they relate to their parents. As the level of relationships with parents increases, the QoL also increases significantly [43]. Hearing loss can affect adolescents’ ability to develop communication and social skills. The sooner DHH adolescents begin receiving services, the more likely they are to reach their total capacity.

Although the findings of the current study explain more precisely the well-being of DHH students, there are some limitations. First, as seen in studies of DHH people, the participants were heterogeneous in their use of different educational methods, communication approaches, cause of hearing loss, and duration of use of hearing aids. These variables may affect the well-being of subjects. Additionally, only DHH adolescents whose reading skills allowed them to complete the questionnaires participated in this study.

The critical strength of this research was the participation of DHH adolescents aged 11–19 years. These results have clinical and educational implications for those psychologists working with DHH adolescents regarding the importance of QoL, health, depression, anxiety, stress, and psychological well-being during the challenging stage of adolescence. Other psychologists could choose a larger sample size. It is recommended to study the psychological well-being of DHH adolescents in clinical and educational environments based on gender and age; It is also suggested to examine the relationship between social skills and self-esteem with the psychological well-being of DHH people.

Technology-based interventions have been applied in Iran to improve mental health and QoL among some population groups. Similar technology-based interventions need to be assessed and applied to DHH adolescents in Iran. Randomized controlled trials need to be designed to evaluate how technology-based interventions can reduce stress and depression among DHH adolescents.

Conclusion

Psychological well-being is considered a combination of positive emotional states and optimal performance in individual and social life. Psychological well-being positively correlated with the QoL, but negatively correlated with psychological distress in DHH adolescents. DHH adolescents may also struggle with various psychological distress. Indeed, the QoL, health, depression, anxiety, and stress in these adolescents can affect their psychological well-being.

This study predicted psychological well-being based on psychosocial factors in DHH adolescents. The findings showed that the QoL, health, depression, anxiety, and stress were significant predictors of the psychological well-being of DHH adolescents. Then, these variables play an important contribution to the well-being of deaf individuals. The results of this study will further help researchers and psychologists reinforce psychotherapy interventions to enhance the components of psychological well-being, QoL, and psychological distress in DHH adolescents.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Human Ethics Research Committee of the University of Isfahan. Informed consent was obtained and the participants were informed that participating in the study was optional.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Mohammad Ashori; Performing the experiment: Bahar Rashidi; Data analysis and writhing the manuscript: Mohammad Ashori and Bahar Rashidi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all deaf adolescents who participated in this study.

References

- Brice PJ, Strauss G. Deaf adolescents in a hearing world: A review of factors affecting psychosocial adaptation. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics. 2016; 7:67-76. [DOI:10.2147/AHMT.S60261] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Hosseinkhani Z, Hassanabadi HR, Parsaeian M, Osooli M, Assari S, Nedjat S. Sources of academic stress among Iranian adolescents: A multilevel study from Qazvin City, Iran. Egyptian Pediatric Association Gazette. 2021; 69(1):1-9. [DOI:10.1186/s43054-021-00054-2]

- Hassanzadeh S, Nikkhoo F. [Parent-child attachment in deaf toddlers: A comparative study (Persian)]. Empowering Exceptional Children. 2019; 10(4):121-30. [DOI:10.22034/ceciranj.2020.213698.1321]

- Hallahan D, Kauffman JM, Pullen P. Exceptional learners: An introduction to special education. London: Pearson; 2023. [Link]

- Rezaiyan F, Movallali G, Adibsereshki N, Bakhshi E. The effectiveness of online dialogic storytelling on vocabulary skills of hard of hearing children. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal. 2020; 18(3):319-28. [DOI:10.32598/irj.18.3.949.1]

- Hassanzadeh S, Nikkhoo F. [Effect of navayesh parent-based comprehensive rehabilitation program on the development of early language and communication skills in deaf children aged 0-2 years (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2017; 17(4):326-37. [DOI:10.21859/jrehab-1704326]

- Aghaziarati A, Ashori M, Norouzi G, Hallahan DP. Mindful parenting: Attachment of deaf children and resilience in their mothers. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 2023; 28(3):300-10. [DOI:10.1093/deafed/enad006] [PMID]

- Grant KE, McMahon SD. Conceptualizing the role of stressors in the development of psychopathology. In: Hankin BL, Abela JRZ, editors. Development of psychopathology: A vulnerability- stress perspective. Los Angeles: Sage; 2005. [DOI:10.4135/9781452231655.n1]

- Young CC, Dietrich MS. Stressful life events, worry, and rumination predict depressive and anxiety symptoms in young adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. 2015; 28(1):35-42. [DOI:10.1111/jcap.12102] [PMID]

- Clak DA, Beck AT, Alford BA. Scientific foundations of cognitive theory and therapy of depression. New York: Wiley; 1999. [Link]

- Sigfusdottir ID, Kristjansson AL, Thorlindsson T, Allegrante JP. Stress and adolescent well-being: The need for an interdisciplinary framework. Health Promotion International. 2017; 32(6):1081-90. [DOI:10.1093/heapro/daw038] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008; 3(5):400-24. [DOI:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x] [PMID]

- Riskind JH, Black D, Shahar G. Cognitive vulnerability to anxiety in the stress generation process: Interaction between the looming cognitive style and anxiety sensitivity. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2010; 24(1):124-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.09.007] [PMID]

- Koohi R, Sajedi F, Movallali G, Dann M, Soltani P. Faranak parent-child mother goose program: Impact on mother-child relationship for mothers of preschool hearing impaired children. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal. 2016; 14(4):201-10. [DOI:10.18869/nrip.irj.14.4.201]

- Gao L, Gan Y, Whittal A, Lippke S. Problematic internet use and perceived quality of life: findings from a cross-sectional study investigating work-time and leisure-time internet use. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(11):4056. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17114056] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Detmar SB, Muller MJ, Schornagel JH, Wever LD, Aaronson NK. Health-related quality-of-life assessments and patient-physician communication: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002; 288(23):3027-34. [DOI:10.1001/jama.288.23.3027] [PMID]

- Jaiyeola MT, Adeyemo AA. Quality of life of deaf and hard of hearing students in Ibadan metropolis, Nigeria. Plos One. 2018; 13(1):e0190130. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0190130] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Dalton DS, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BE, Klein R, Wiley TL, Nondahl DM. The impact of hearing loss on quality of life in older adults. The Gerontologist. 2003; 43(5):661-8. [DOI:10.1093/geront/43.5.661] [PMID]

- Yaribakht M, Movallali G. The effects of an early family-centered tele-intervention on the preverbal and listening skills of deaf children under tow years old. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal. 2020; 18(2):117-24. [DOI:10.32598/irj.18.2.186.4]

- Duncan J, Colyvas K, Punch R. Social capital, loneliness, and peer relationships of adolescents who are deaf or hard of hearing. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 2021; 26(2):223-9. [DOI:10.1093/deafed/enaa037] [PMID]

- Wiseman KB, Warner-Czyz AD, Nelson JA. Stress in parents of school-age children and adolescents with cochlear implants. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 2021; 26(2):209-22. [DOI:10.1093/deafed/enaa042] [PMID]

- Adibsereshki N, Hatamizadeh N, Sajedi F, Kazemnejad A. Well-being and coping capacities of adolescent students with hearing loss in mainstream schools. Iranian Journal of Child Neurology. 2020; 14(1):21-30. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Adigun OT. Self-esteem, self-efficacy, self-concept and intimate image diffusion among deaf adolescents: A structural equation model analysis. Heliyon. 2020; 6(8):e04742. [DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04742] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kushalnagar P, Topolski TD, Schick B, Edwards TC, Skalicky AM, Patrick DL. Mode of communication, perceived level of understanding, and perceived quality of life in youth who are deaf or hard of hearing. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 2011; 16(4):512-23. [DOI:10.1093/deafened/enr015] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Fellinger J, Holzinger D, Sattel H, Laucht M. Mental health and quality of life in deaf pupils. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008; 17(7):414-23. [DOI:10.1007/s00787-008-0683-y] [PMID]

- Chia EM, Wang JJ, Rochtchina E, Cumming RR, Newall P, Mitchell P. Hearing impairment and health-related quality of life: The blue mountains hearing study. Ear and Hearing. 2007; 28(2):187-95. [DOI:10.1097/AUD.0b013e31803126b6] [PMID]

- Ashori M, Jalil-Abkenar SS. Emotional intelligence: Quality of life and cognitive emotion regulation of deaf and hard-of-hearing adolescents. Deafness & Education International. 2021; 23(2):84-102. [DOI:10.1080/14643154.2020.1766754]

- Ashori M. [Lived experience of the normal-hearing adolescents of parents with severe and profound hearing impairment: A qualitative study with a phenomenological approach (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2022; 23(1):32-49 [DOI:10.32598/RJ.23.1.655.16]

- Robitail S, Ravens-Sieberer U, Simeoni MC, Rajmil L, Bruil J, Power M, et al. Testing the structural and cross-cultural validity of the KIDSCREEN-27 quality of life questionnaire. Quality of Life Research. 2007; 16(8):1335-45. [DOI:10.1007/s11136-007-9241-1] [PMID]

- Nik-Azin A, Naeinian MR, Shairi MR. [Validity and reliability of health related quality of life questionnaire “KIDSCREEN-27” in a sample of iranian students (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry & Clinical Psychology. 2013; 18(4):310-21. [Link]

- Patrick DL, Edwards TC, Skalicky AM, Schick B, Topolski TD, Kushalnagar P, et al. Validation of a quality-of-life measure for deaf or hard of hearing youth. Otolaryngology--Head and Neck Surgery . 2011; 145(1):137-45. [DOI:10.1177/0194599810397604] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Ashori M, Rashidi A. [Investigate the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the youth quality of life instrument-deaf and hard of hearing(YQOL-DHH) (Persian)]. Social Work. 2020; 9(2):48-59. [Link]

- Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. Manual for the depression anxiety & stress scales. Sydney: Psychology Foundation of Australia; 1996. [Link]

- Crawford JR, Henry JD. The depression anxiety stress scales (DASS): Normative data and latent structure in a large non-clinical sample. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003; 42(Pt 2):111-31. [DOI:10.1348/014466503321903544] [PMID]

- Antony MM, Bieling PJ, Cox BJ, Enns MW, Swinson RP. Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the depression anxiety stress scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychological Assessment. 1998; 10(2):176-81. [DOI:10.1037/1040-3590.10.2.176]

- Samani S, Jokar B. Evaluate the reliability and validity of the short form of depression, anxiety, and stress. J Social Sci Humanities Shiraz University. 2007; 26(3): 65-76. [Link]

- Field AP. Discovering statistics using SPSS (and sex and drugs and rock ‘n’roll). London: Sage Publications; 2009. [Link]

- Pallant J. SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS for windows version 15. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin; 2007. [Link]

- Ashori M, Rashidi A. Effectiveness of cognitive emotion regulation on emotional intelligence in students with hearing impairment. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal. 2020; 18(3):239-48. [DOI:10.32598/irj.18.3.188.6]

- Rostami S, Alizadeh H, Rezayi S, Nikkhoo F, Hemmatialamdar G. Developing a rehabilitation program based on working memory and its effectiveness on word recognition in children with hearing impairment. Journal of Exceptional Education. 2023; 1(173):92. [Link]

- Nemati S. [Lived experiences and challenges of mothers with children with hearing impairments: A phenomenological study (Persian)]. Quarterly Journal of Child Mental Health. 2020; 6(4):305-15. [DOI:10.29252/jcmh.6.4.27]

- Hintermair M. Health-related quality of life and classroom participation of deaf and hard-of-hearing students in general schools. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 2011; 16(2):254-71. [DOI:10.1093/deafed/enq045] [PMID]

- Movallali G, Seyyed Noori SZ. Choosing appropriate communication: Approach for children with hearing loss. Journal of Exceptional Education. 2017; 6(143):51-60. [Link]

Article type: Original Research Articles |

Subject:

Psychology

Received: 2022/11/18 | Accepted: 2023/10/11 | Published: 2024/03/1

Received: 2022/11/18 | Accepted: 2023/10/11 | Published: 2024/03/1

Send email to the article author