Volume 22, Issue 3 (September 2024)

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2024, 22(3): 449-458 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: The research has passed Ciputra University School of Medicine ethics clearance with letter number 03

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Sanjaya E L, Suminar D R, Fardana N A. Investigating the Adaptation of the Father Nurturance Scale: Validation for Adolescents in Indonesia. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2024; 22 (3) :449-458

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1978-en.html

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1978-en.html

Investigating the Adaptation of the Father Nurturance Scale: Validation for Adolescents in Indonesia

1- Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia.

Full-Text [PDF 536 kb]

(2072 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3793 Views)

Full-Text: (716 Views)

Introduction

The paternal figure’s involvement in the nurturing and development of offspring has experienced substantial changes throughout history. In the era of Puritanism, the father’s primary focus was on imparting moral lessons and instilling religious principles. Subsequently, in the 1920s, amidst America’s Industrial Revolution, the father assumed a more singular responsibility as the provider for the family. Following this, during the Second World War and the subsequent global economic crisis of the late 1940s, the role of the father evolved into that of an exemplary figure, particularly for sons, devoid of any sexual characteristics. Considering the multifarious alterations in the environment, contemporary scholars have recognized the necessity to redefine the role of the father, leading to more active involvement in the act of parenting [1]. In the context of Asia, specifically Indonesia, Bemmelen demonstrated that the responsibility of parenting is predominantly shouldered by women. The father must serve as the primary earner and is primarily concerned with personal, ethical and spiritual growth. The distinct delineation of roles implies that mothers do not actively encourage fathers to participate in the upbringing of their offspring, consequently resulting in fathers’ limited involvement in child-rearing [2].

However, research over the past 20 years has revealed that paternal involvement in parenting has positive impacts on child development. Several studies have indicated that the participation of fathers in parenting has a significant influence on multiple facets of child development, such as the temperament observed in children of preschool age [3], children’s cognitive abilities [4], language skills [5], secure attachment styles [6], a lower level of problem behavior [7, 8] and psychopathological symptoms such as depression and antisocial traits [9, 10], and an increase in entrepreneurial intentions among late teens [11]. This is because there is a significant disparity in the extent of research conducted on maternal involvement in parenting as compared to research conducted on paternal involvement in parenting [12, 13]. In addition, according to the Ministry of Women’s Empowerment and Child Protection, Indonesia is recognized as one of the countries constituting the top ten nations worldwide in terms of the highest number of children lacking paternal care or in need of fatherly affection within the realm of childcare [14]. For this reason, it is important to continue conducting studies of father care in the Indonesian context, starting with a valid scale.

Father nurturance conceptualized

The pioneering work on the involvement of fathers in parenting was conducted by Lamb [15]. Lamb et al. proposed a conceptual framework consisting of three distinct dimensions about the involvement of fathers in the process of parenting. The first dimension, referred to as interaction, entails the direct engagement between a father and his child through various parenting activities and shared experiences. The second dimension, denoted as availability, focuses on the father’s accessibility and willingness to be physically present and engage directly with his child. Lastly, the third dimension, responsibility, encompasses the time spent by the father in interacting with his child, and his crucial role in ensuring the overall well-being and fulfillment of his child’s needs through the provision of specific resources. Studying a father’s involvement in parenting is multidimensional, necessitating a comprehensive approach to its exploration and understanding [15].

Lamb’s approach focused primarily on measuring the time fathers spent with their children and often overlooked the nature and content of parenting [16, 17]; however, examining the father’s involvement in parenting solely from the perspective of time-based interactions does not provide a true measure of the impact that a father’s parenting has on his child, particularly in the case of fathers living with their children permanently [16]. Hawkins et al. attempted to broaden and enrich the concept of the father’s involvement in parenting over the previous approach by examining only the father’s involvement in parenting, which was limited to time spent with the child [17]. Hawkins et al. have formulated an inventory of father involvement which encompasses a total of nine dimensions for measurement. These dimensions include the following items: 1) The exercise of discipline and the assumption of teaching responsibility, 2) The encouragement of scholastic pursuits, 3) The support provided by the mother, 4) The act of provision, 5) The allocation of time for shared conversation, 6) The expression of praise and affection, 7) The cultivation of talents and the fostering of concerns for the future, 8) The facilitation of reading and assistance with homework and 9) The demonstration of attentiveness [17].

Finley and Schwartz took a different approach to examining the father’s involvement in parenting by exploring the child’s perspective. The main essence of Finley and Schwartz argues that a child’s future behavior is a retrospective perception of his parents. When a teenager or adult perceives that their father is present and involved in their life, at perception affects their current behavior. Several factors serve as the foundation for this notion. Firstly, father involvement in parenting is a highly diverse concept, encompassing numerous domains through which children can be impacted. Secondly, the significance that children attach to their perception of their father’s involvement surpasses the importance placed on the actual amount of time spent together. Thirdly, the long-term consequences of a father’s involvement in parenting warrant examination. Lastly, the most effective approach to evaluating the enduring effects involves studying the perceptions of teenagers or adults regarding their father’s past involvement. These aspects establish the imperative nature of investigating the father’s involvement in parenting from the child’s standpoint. Finley and Schwartz formulated the nurturance fathering scale (NFS) to evaluate paternal caregiving through the lens of the child [16].

Father nurturance in the context of adolescents

Understanding paternal care in the context of adolescents is of utmost importance. By adopting an ecological approach, adolescent issues can be linked to internal family patterns. Father nurturance is one family pattern that can provide an overview of an adolescent’s overall picture [18]. The presence of a father figure in an adolescent’s life affects their life satisfaction in a crisis [19]. In their longitudinal study, Flauri and Buchanan found that the presence of a father in the life of a 16-year-old helps him deal with and cope with the stress he faces around the age of 30 years [20]. Several studies have also highlighted the positive relationship between adolescent self-esteem and the presence of their father in their life [21, 22]. The presence and involvement of a father in the life of adolescents is an important factor in their development, and the lack of a father figure has specific implications for young people [23].

Based on the previous review, the primary objective of the current study is to validate the NFS developed by Finley and Schwartz [16] in the context of Indonesian adolescents. Overall, the need for the current study builds on previous research showing that an adolescent’s perception of whether or not their father accepts them has an impact on their emotional, psychological, and behavioral development [24]. Therefore, it is crucial to acquire a deeper comprehension of the repercussions stemming from the participation of a paternal figure in teenagers within Indonesia. By having a measuring tool that can observe what adolescents feel regarding parenting and the presence of fathers, we will have a better understanding of whether the father's role in parenting is optimal, especially from the child's perspective. This instrument of measurement can also serve as a quantifiable assessment of the extent to which initiatives aimed at enhancing paternal engagement in child-rearing truly yield beneficial outcomes for young individuals in the Indonesian context. In addition, by having a validated measuring tool, knowledge about fathers' parenting, especially in Indonesia, where fathers are not considered the main caregivers, will grow. This makes this research have many benefits.

Materials and Methods

The scale adaptation process uses the flow proposed by Beaton et al. [25]. Before the adaptation stage started, we emailed Finley and Schwartz to ask for permission to adapt the original NFS. Afterward, the initial phase of the scale adaptation procedure involves the process of forward translation, wherein the scale in the original language is linguistically transformed into the desired language. The second stage is carrying out back translation, namely the scale that has been translated into the target language and then is translated back into the original language. The third stage is to carry out a synthesis where a comparison is made between the original scale and the scale resulting from back translation to see whether there is a difference in meaning between the original scale and the translated scale. If there is a difference in meaning, the synthesizer will adjust so that the meaning remains the same. The translation process is carried out by different linguists at each stage. The fourth stage is to provide the translated scale to 2 experts. Experts will assess 4 aspects of equality according to Beaton et al. [25], namely semantic equivalence, idiomatic equivalence, experiential equivalence and conceptual equivalence. Based on the expert’s assessment, a content validity index (CVI) was found. The CVI range of each item was 0.85-1. For the overall CVI results, the score was 0.96. These results indicate that the content validity of the NFS adaptation is quite good. The next stage is to test construct validity by looking at the internal structure of the scale using exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

The data were collected through self-reporting using the NFS. Finley and Schwartz [16] developed this measuring tool in the context of students in America. Accordingly, the NFS produced an adequate fit to the data with one factor (χ2, P<0.001, comparative fit index [CFI]=0.99, root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA]=0.11).

Factor pattern coefficients ranged from 0.50 to 0.85. Meanwhile, the Cronbach α score was 0.94. In this research, the scale was distributed using Google Forms together with an informed consent form. Construct validity was determined for the scale using CFA. CFA is used in situations where a researcher already possesses knowledge and understanding of the dimensions of a scale based on theories and empirical findings from previous studies [26]. The data were tested using the JASP software. The scale consists of eight items ranging from one to five. Each question has a unique answer response, with the numbers by question. The complete items and their responses can be found in the appendices. The total number of respondents to the study was 324 adolescents.

Results

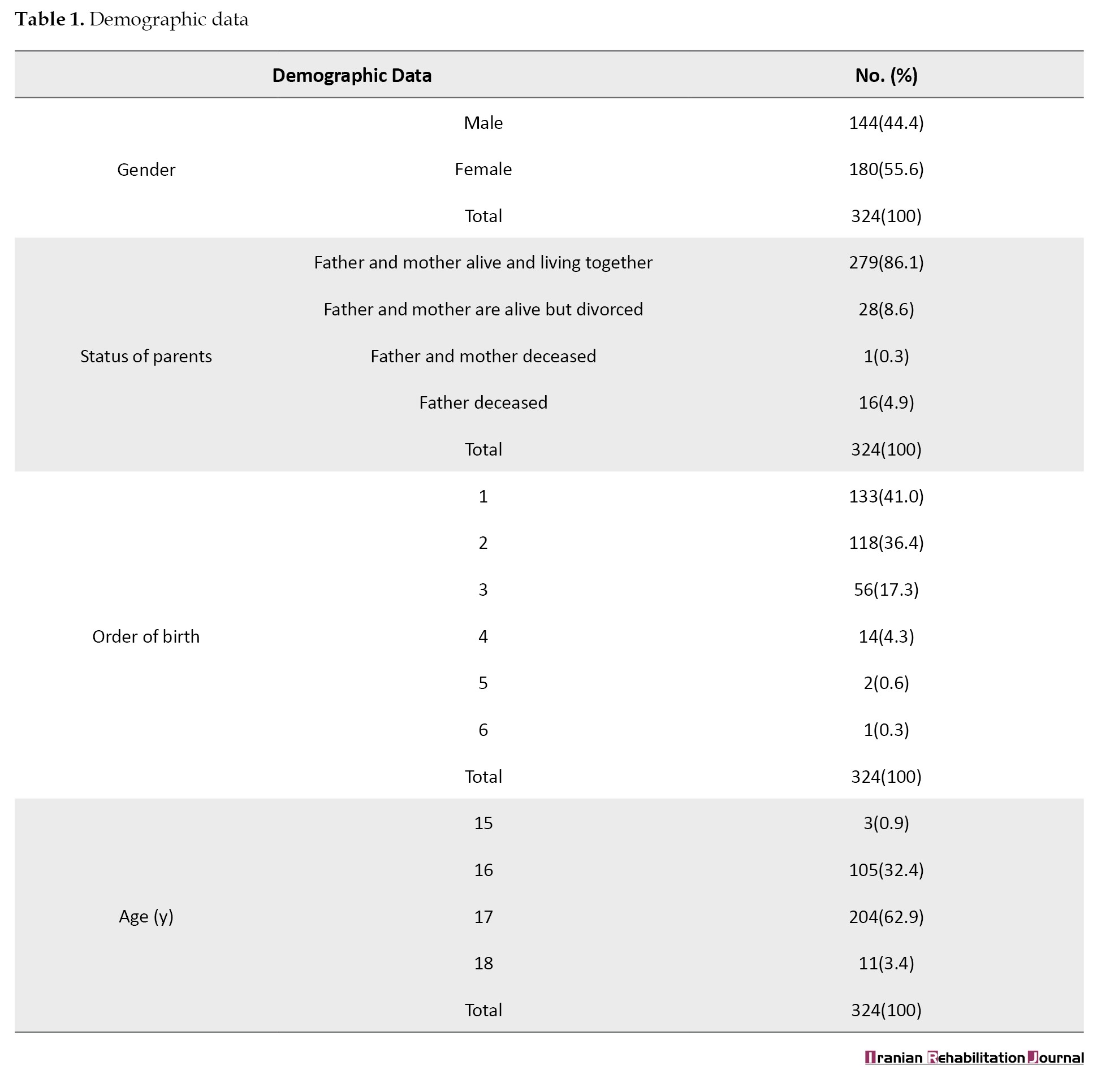

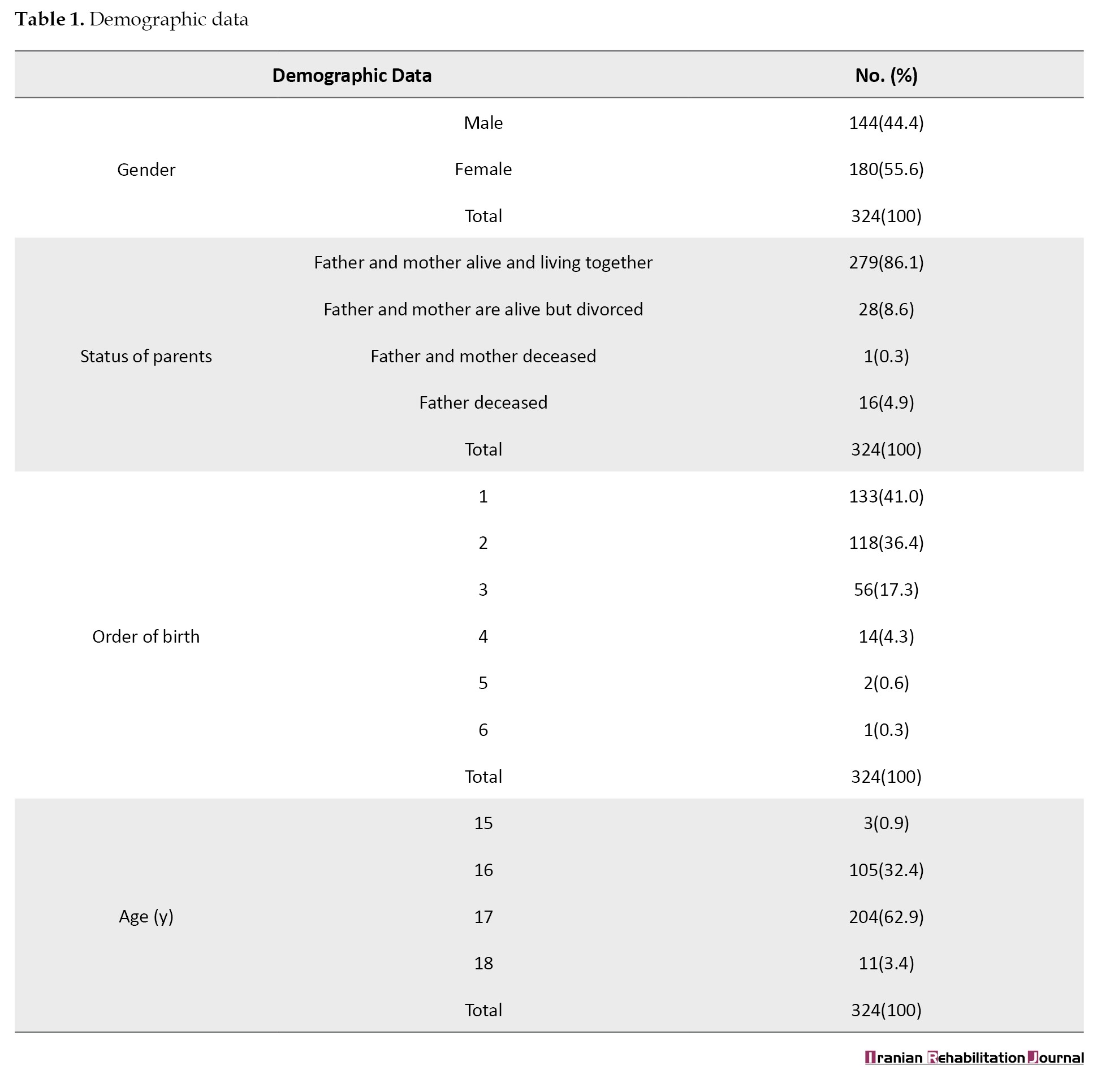

The demographic presented in Table 1 shows that the age range of respondents was between 15 and 18 years, with the majority of respondents being 17 years old (62.9%).

The majority of respondents came from families where both father and mother survived and lived together (86.1%). The gender of the respondents was relatively balanced between men (44.4%) and women (55.6%).

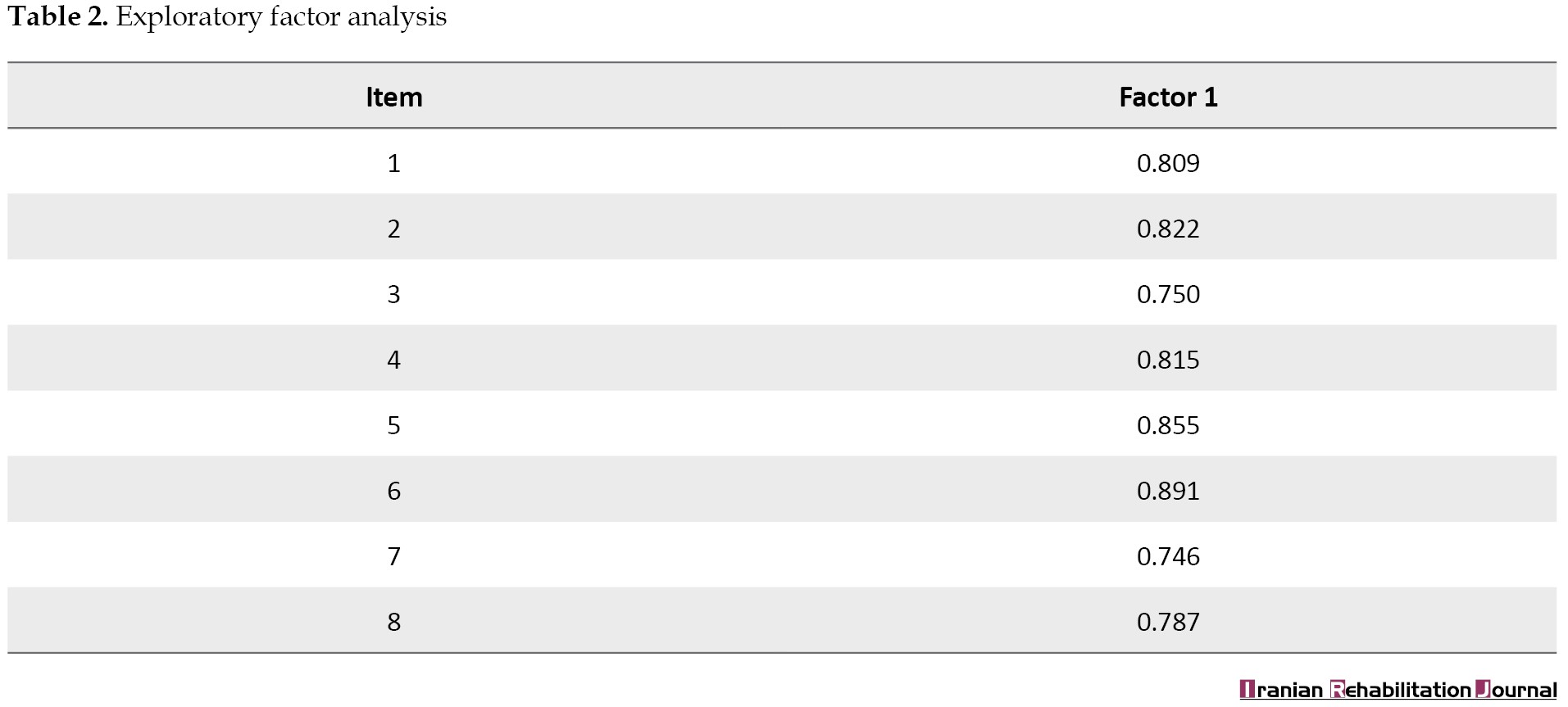

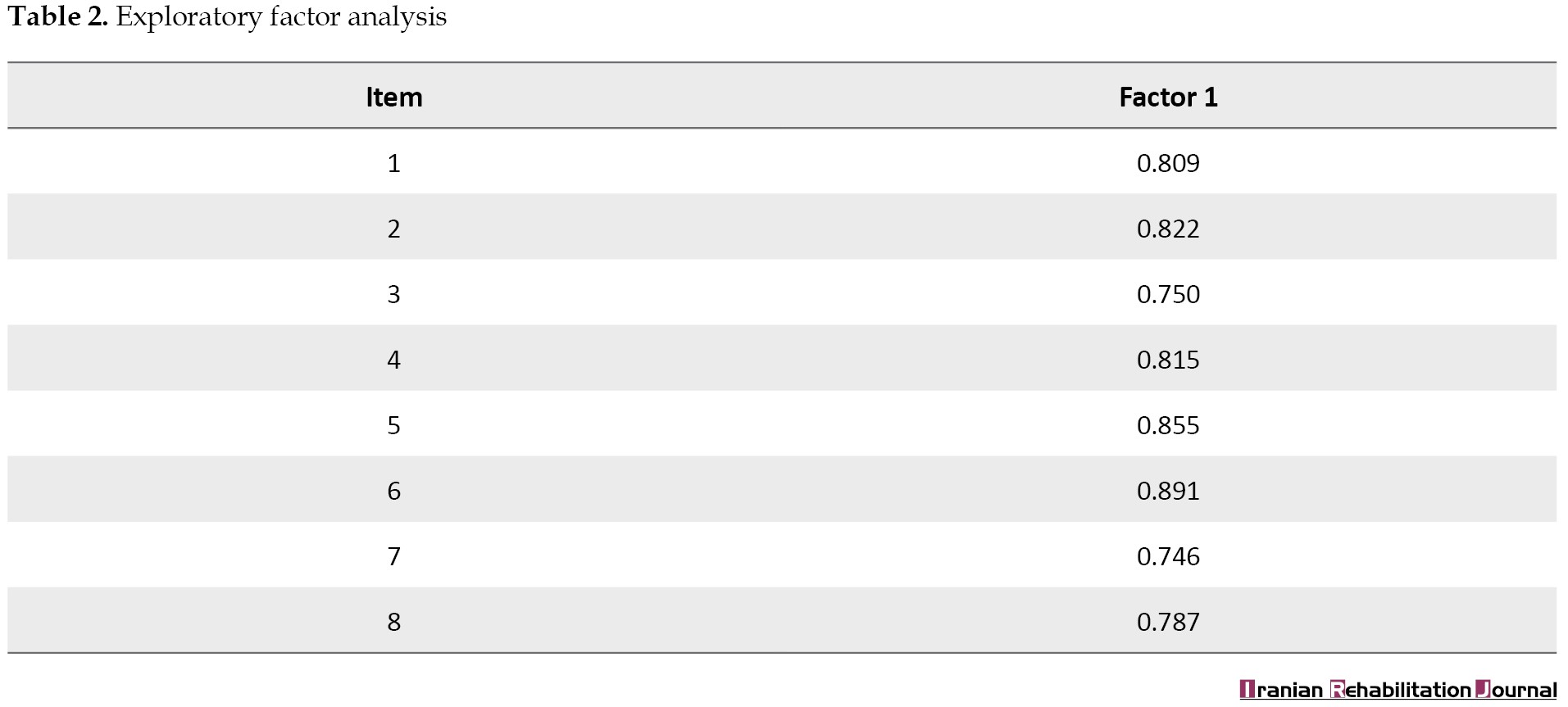

Before evaluating the model, a preliminary examination of the data was performed, using EFA to observe the dispersion of item clusters derived from the scale. Based on the EFA results (Table 2), the items from the NFS were grouped into one factor; accordingly, the NFS was unidimensional.

This is following the original NFS scale designed by Finley and Schwartz. Based on the results of the EFA, the next process is CFA with 1 factor to see the fit model of this measuring instrument.

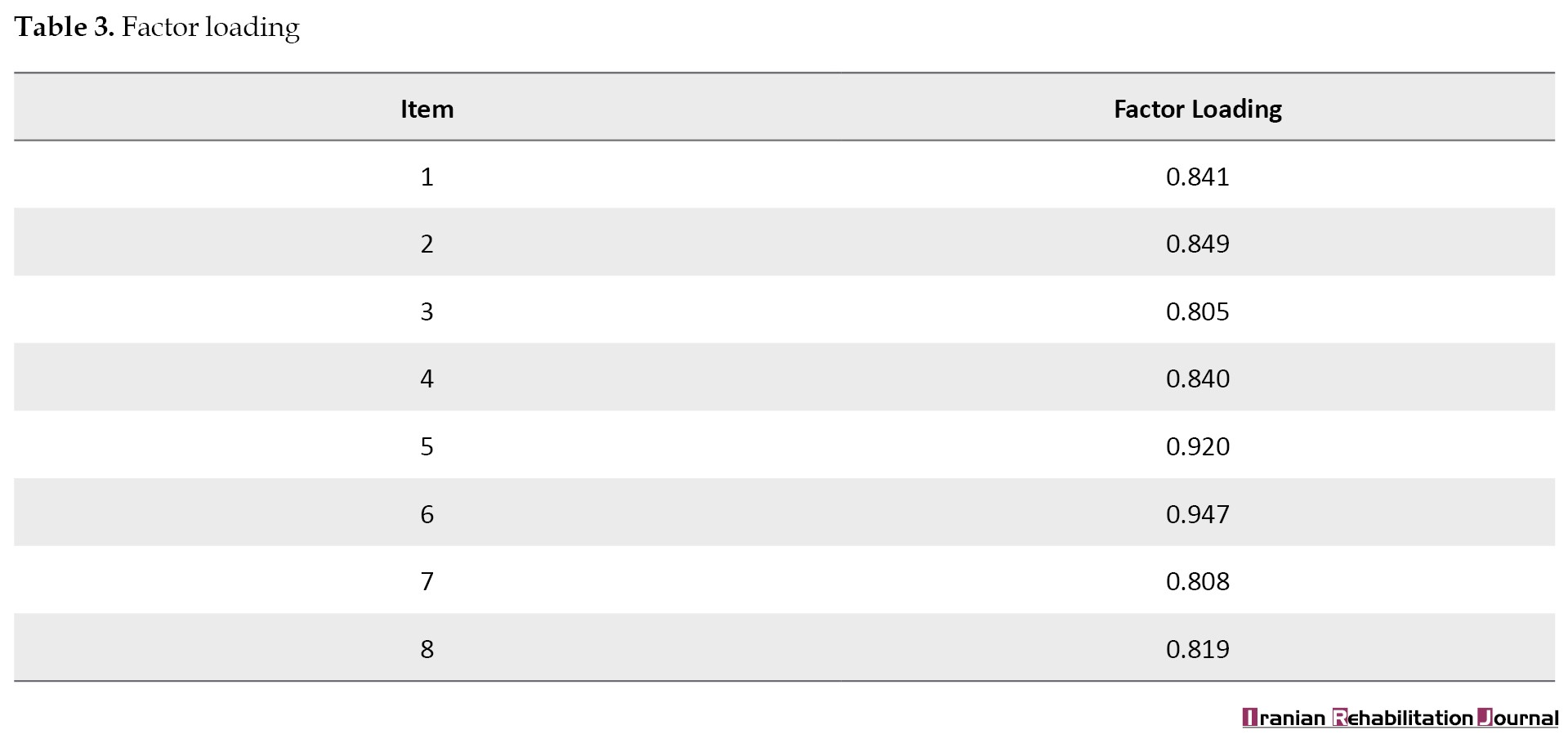

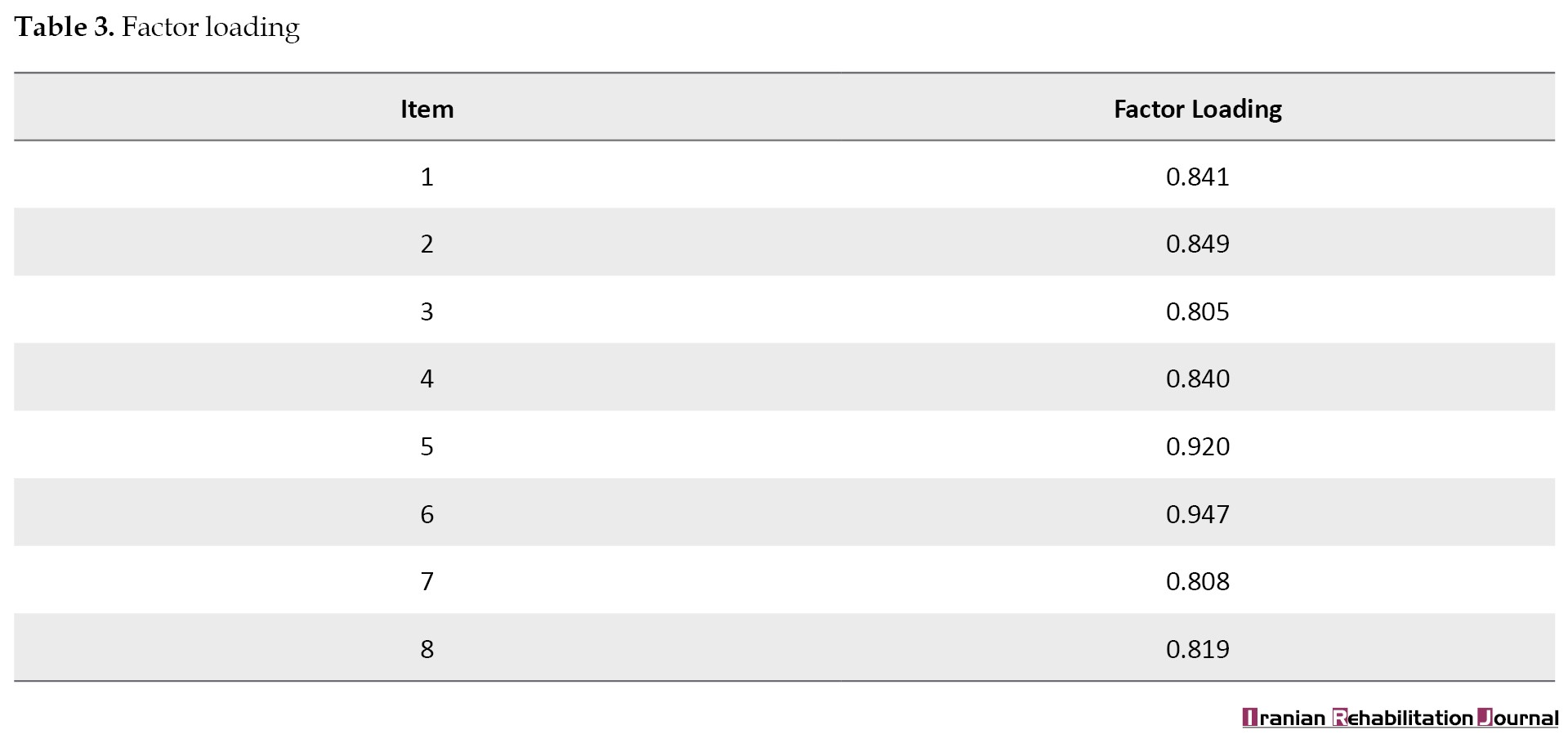

Factor loading for the eight-item model of the Indonesian version of the NFS for adolescents ranged from 0.808 to 0.947 (Table 3).

Factor loading illustrates the relationship between indicators and latent variables [27]. Brown argued that 0.3 was the minimum limit of factor loading, while Ford stated that 0.4 was the lower limit of factor loading [26, 28]. Based on these calculations, the items of the Indonesian version of the NFA intended for adolescents represent aspects that we wished to measure father nurturance.

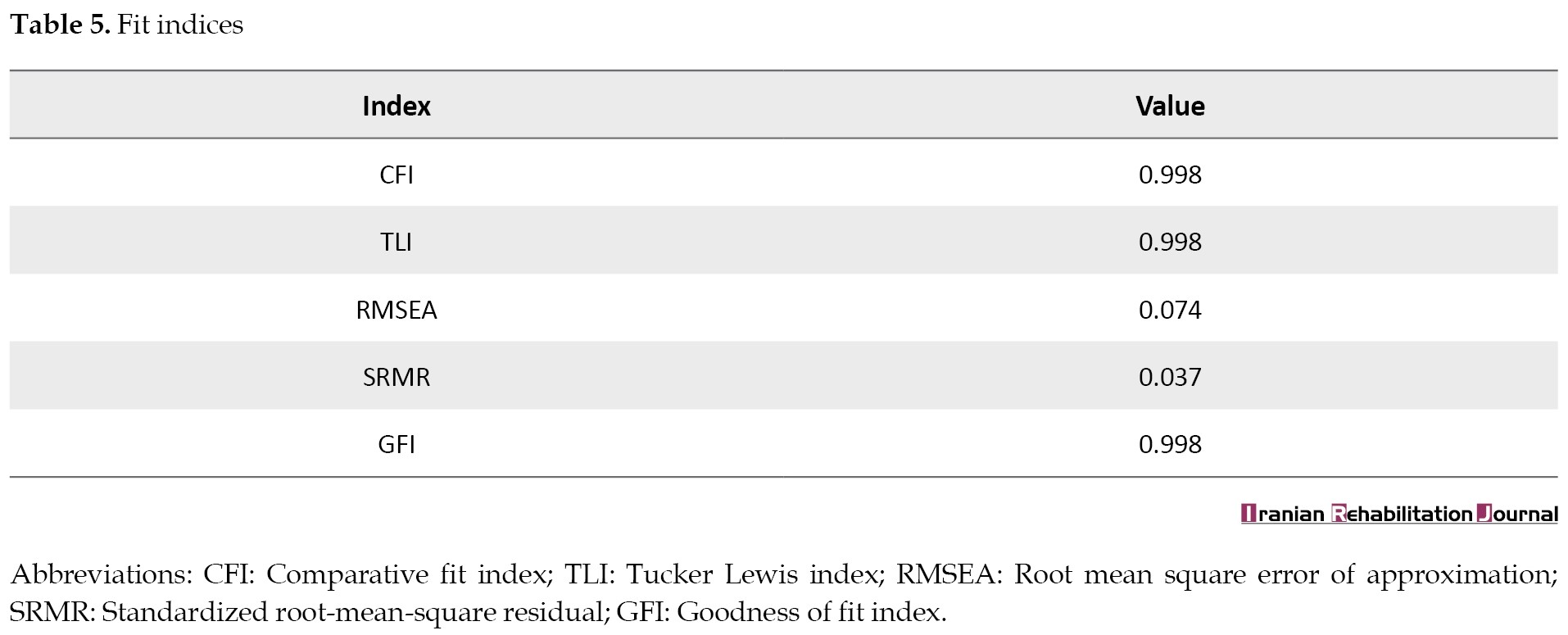

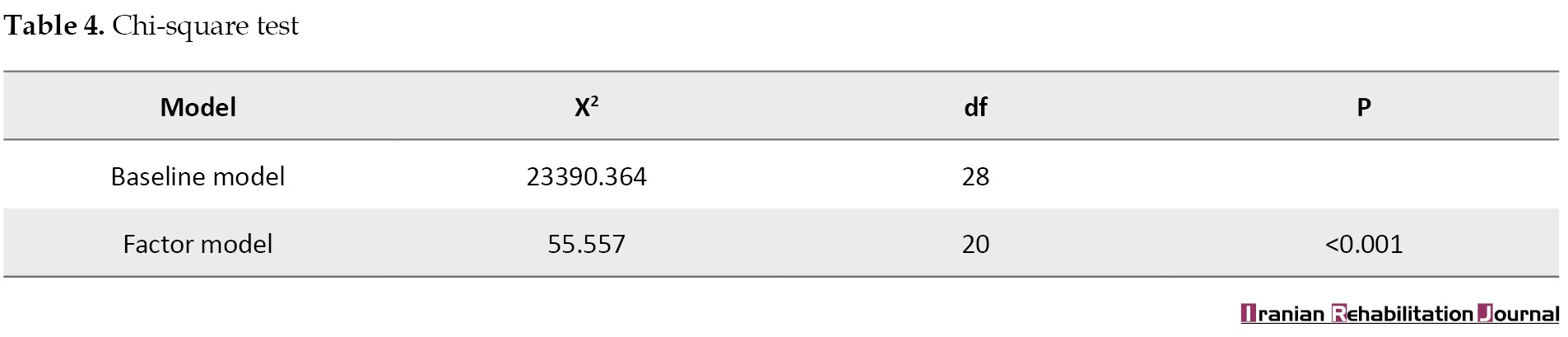

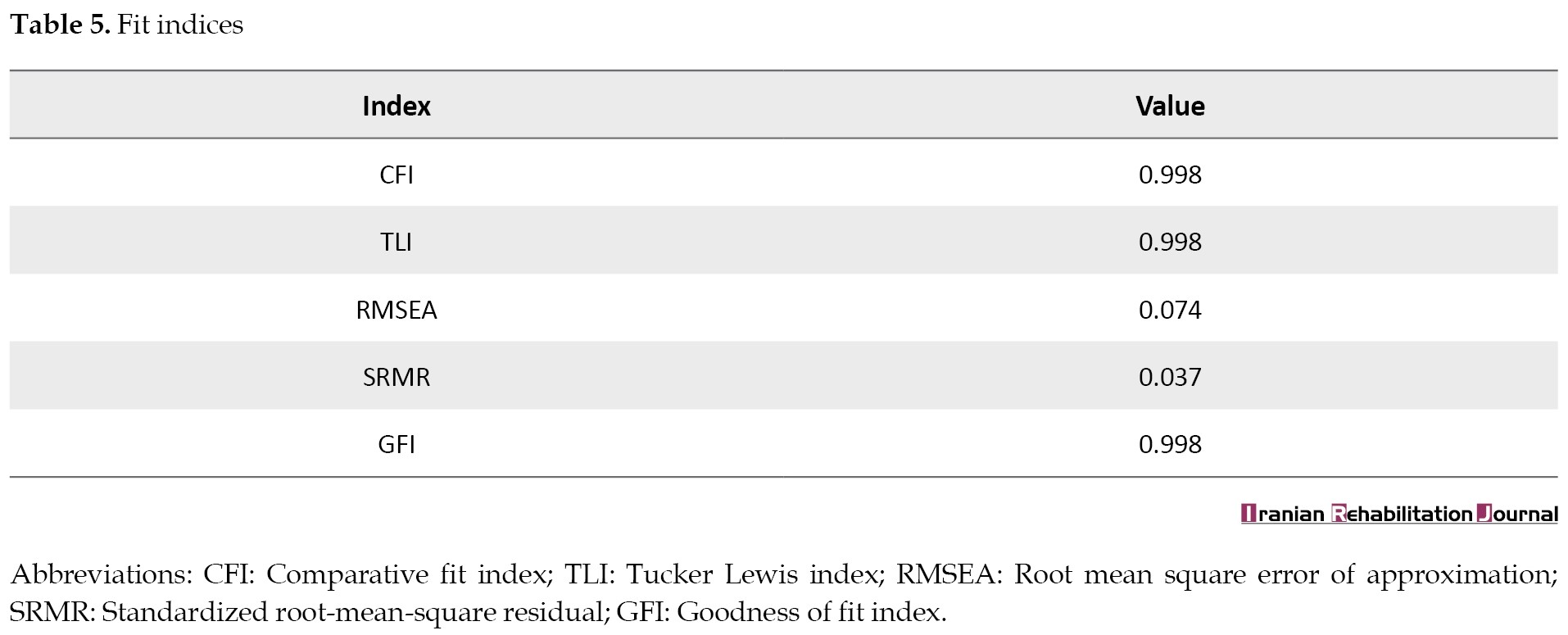

The criterion employed to evaluate the appropriateness of the model utilized in the present study was the CFI, which necessitates a minimum value of 0.9 to be regarded as appropriate. Additionally, the Tucker-Lewis index, with an anticipated value exceeding 0.9, is encompassed within the incremental fit indices [27]. The present investigation additionally scrutinized the approximation of the RMSEA, whereby the threshold value is <0.8 and the standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR), with the threshold value being <0.08. Both of these values are encompassed within the absolute fit indices [26, 27, 29]. The chi-square value is anticipated to be greater than 0.05, indicating no discernible distinction between the model and the data [30]. However, the chi-square statistic exhibits a high degree of sensitivity concerning the number of observations. As the sample size increases, the estimation findings tend to become statistically significant. Consequently, the suitability of the model is deemed inadequate; therefore, for the current research, the chi-square values were calculated, but not used as material for the analysis.

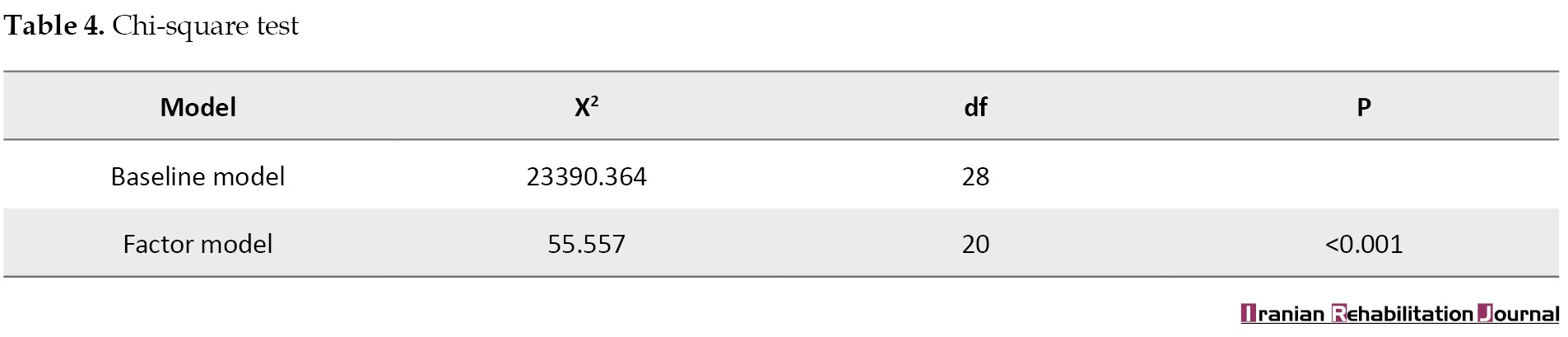

A chi-square value was calculated to be <0.001 for the current study (Table 4).

However, due to the susceptibility of chi-square values to the size of the sample, the aforementioned value was not incorporated into the examination of the research study. The study obtained the following values: CFI=0.998, Tucker Lewis index (TLI)=0.998, RMSEA=0.074, SRMR=0.037. Based on the results, the NFS adapted into the Indonesian language is a fit model. Reliability was assessed through the utilization of Cronbach α, yielding a score of 0.938. Furthermore, the range of item-rest correlations was observed to fall within 0.762-0.858 (Table 5).

Discussion

This study examined the validity of the NFS after it had been modified to suit Indonesian adolescents. Through the adaptation process, an eight-item Indonesian-language NFS was standardized for adolescents, finding that the internal structure corresponds to a model fit. item number seven (“overall, how would you rate your father?”) was determined to have the lowest factor loading. However, the range of factor loading for the Indonesian version of the NFS for the context of adolescents was 0.808-0.998, suggesting that all items are capable of illustrating what we intended to measure father nurturance. In addition, based on several fit indices, the Indonesian version of the father nurturance scale was determined to be fit. Accordingly, the scale is suitable for use after adaptation to the Indonesian language and the specific context of adolescents.

The significance of the Indonesian scale’s progress lies in the pivotal role that fathers assume in the advancement of adolescents. Additionally, within patriarchal settings like Indonesia, the engagement of fathers in child-rearing and their active presence in their children’s lives do not arise inherently [31]. The development of an NFS for adolescents in Indonesia can be beneficial in measuring how adolescents perceive their father’s presence in their lives. This information can then be used as a reference for decision-making by relevant institutions, including educational and government institutions [18].

There is an ongoing debate about the reliability of scales that measure concepts retrospectively, such as the NFS, since the results are highly dependent on the respondent’s memory process [18]. However, as Finley and Schwartz argue, retrospective measurements may not be objective, but a person’s subjective perception of their past concerning their father’s presence is more important than objectivity since this perception influences every phase of their development and current state [16]. Meanwhile, the effects of a father’s child-rearing on his offspring endure over time, thus, the creation of this measurement tool has the potential to enhance long-range investigations in the forthcoming years [32].

The present investigation discovered that the adapted iteration of the father nurturance scale in the Indonesian language exhibits commendable internal validity and can be effectively employed for subsequent investigations. However, there are a few ways to make the scale more robust. The validity of the scale should be tested in different population contexts so that its use can be more widespread, and can be used in different research contexts in the future.

Conclusion

The primary aim of this study was to modify NFS for the Indonesian context, with a specific focus on adolescents. This is considered important as previous studies have shown the importance of the father’s role in adolescent development; however, the role of fathers in Indonesia is still not optimal. The findings of this research demonstrated that the NFS instrument, when adjusted to the specific circumstances of Indonesia, exhibits a satisfactory level of reliability, rendering it suitable for application in future investigations. Suggestions for future research are to try to validate NFS in wider cultural contexts and also try to correlate it with other variables.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Ciputra University (Code: 034/EC/KEPK-FKUC/X/2022).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Faculty of Psychology, Airlangga University and the Faculty of Psychology, Ciputra University for supporting this research.

References

Appendix 1.

Indonesian Version of NFS

1. Menurut Anda, seberapa menikmati ayah Anda menjadi menjadi seorang ayah?

_____ sama sekali tidak menikmati

_____ tidak menikmati

_____ terkadang menikmati

_____ menikmati

_____ sangat menikmati

2. Ketika Anda membutuhkan dukungan ayah Anda, apakah dia ada untuk Anda?

_____ tidak pernah ada

_____ jarang ada

_____ terkadang ada

_____ seringkali ada

_____ selalu ada

3. Apakah ayah Anda memiliki cukup energi untuk memenuhi kebutuhan Anda?

_____ tidak pernah

_____ jarang

_____ terkadang

_____ sering

_____ selalu

4. Apakah ayah Anda memiliki waktu untuk dihabiskan berkegiatan bersama Anda?

_____ tidak pernah

_____ jarang

_____ terkadang

_____ sering

_____ selalu

5. Seberapa dekat Anda secara emosional dengan ayah Anda?

_____ tidak pernah

_____ jarang

_____ terkadang

_____ sering

_____ selalu

6. Dalam masa remaja Anda, seberapa akrab Anda dengan ayah Anda?

_____ sangat tidak akrab

_____ tidak akrab

_____ cukup akrab

_____ akrab

_____ sangat akrab

7. Secara keseluruhan, bagaimana Anda menilai ayah Anda

_____ sangat buruk

_____ buruk

_____ cukup

_____ baik

_____ sangat luar biasa

8. Saat Anda menjalani hari Anda, seberapa besar kehadiran psikologis ayah Anda dalam pikiran dan perasaan Anda sehari-hari?

_____ tidak pernah ada

_____ jarang ada

_____ terkadang ada

_____ sering ada

_____ selalu ada

The paternal figure’s involvement in the nurturing and development of offspring has experienced substantial changes throughout history. In the era of Puritanism, the father’s primary focus was on imparting moral lessons and instilling religious principles. Subsequently, in the 1920s, amidst America’s Industrial Revolution, the father assumed a more singular responsibility as the provider for the family. Following this, during the Second World War and the subsequent global economic crisis of the late 1940s, the role of the father evolved into that of an exemplary figure, particularly for sons, devoid of any sexual characteristics. Considering the multifarious alterations in the environment, contemporary scholars have recognized the necessity to redefine the role of the father, leading to more active involvement in the act of parenting [1]. In the context of Asia, specifically Indonesia, Bemmelen demonstrated that the responsibility of parenting is predominantly shouldered by women. The father must serve as the primary earner and is primarily concerned with personal, ethical and spiritual growth. The distinct delineation of roles implies that mothers do not actively encourage fathers to participate in the upbringing of their offspring, consequently resulting in fathers’ limited involvement in child-rearing [2].

However, research over the past 20 years has revealed that paternal involvement in parenting has positive impacts on child development. Several studies have indicated that the participation of fathers in parenting has a significant influence on multiple facets of child development, such as the temperament observed in children of preschool age [3], children’s cognitive abilities [4], language skills [5], secure attachment styles [6], a lower level of problem behavior [7, 8] and psychopathological symptoms such as depression and antisocial traits [9, 10], and an increase in entrepreneurial intentions among late teens [11]. This is because there is a significant disparity in the extent of research conducted on maternal involvement in parenting as compared to research conducted on paternal involvement in parenting [12, 13]. In addition, according to the Ministry of Women’s Empowerment and Child Protection, Indonesia is recognized as one of the countries constituting the top ten nations worldwide in terms of the highest number of children lacking paternal care or in need of fatherly affection within the realm of childcare [14]. For this reason, it is important to continue conducting studies of father care in the Indonesian context, starting with a valid scale.

Father nurturance conceptualized

The pioneering work on the involvement of fathers in parenting was conducted by Lamb [15]. Lamb et al. proposed a conceptual framework consisting of three distinct dimensions about the involvement of fathers in the process of parenting. The first dimension, referred to as interaction, entails the direct engagement between a father and his child through various parenting activities and shared experiences. The second dimension, denoted as availability, focuses on the father’s accessibility and willingness to be physically present and engage directly with his child. Lastly, the third dimension, responsibility, encompasses the time spent by the father in interacting with his child, and his crucial role in ensuring the overall well-being and fulfillment of his child’s needs through the provision of specific resources. Studying a father’s involvement in parenting is multidimensional, necessitating a comprehensive approach to its exploration and understanding [15].

Lamb’s approach focused primarily on measuring the time fathers spent with their children and often overlooked the nature and content of parenting [16, 17]; however, examining the father’s involvement in parenting solely from the perspective of time-based interactions does not provide a true measure of the impact that a father’s parenting has on his child, particularly in the case of fathers living with their children permanently [16]. Hawkins et al. attempted to broaden and enrich the concept of the father’s involvement in parenting over the previous approach by examining only the father’s involvement in parenting, which was limited to time spent with the child [17]. Hawkins et al. have formulated an inventory of father involvement which encompasses a total of nine dimensions for measurement. These dimensions include the following items: 1) The exercise of discipline and the assumption of teaching responsibility, 2) The encouragement of scholastic pursuits, 3) The support provided by the mother, 4) The act of provision, 5) The allocation of time for shared conversation, 6) The expression of praise and affection, 7) The cultivation of talents and the fostering of concerns for the future, 8) The facilitation of reading and assistance with homework and 9) The demonstration of attentiveness [17].

Finley and Schwartz took a different approach to examining the father’s involvement in parenting by exploring the child’s perspective. The main essence of Finley and Schwartz argues that a child’s future behavior is a retrospective perception of his parents. When a teenager or adult perceives that their father is present and involved in their life, at perception affects their current behavior. Several factors serve as the foundation for this notion. Firstly, father involvement in parenting is a highly diverse concept, encompassing numerous domains through which children can be impacted. Secondly, the significance that children attach to their perception of their father’s involvement surpasses the importance placed on the actual amount of time spent together. Thirdly, the long-term consequences of a father’s involvement in parenting warrant examination. Lastly, the most effective approach to evaluating the enduring effects involves studying the perceptions of teenagers or adults regarding their father’s past involvement. These aspects establish the imperative nature of investigating the father’s involvement in parenting from the child’s standpoint. Finley and Schwartz formulated the nurturance fathering scale (NFS) to evaluate paternal caregiving through the lens of the child [16].

Father nurturance in the context of adolescents

Understanding paternal care in the context of adolescents is of utmost importance. By adopting an ecological approach, adolescent issues can be linked to internal family patterns. Father nurturance is one family pattern that can provide an overview of an adolescent’s overall picture [18]. The presence of a father figure in an adolescent’s life affects their life satisfaction in a crisis [19]. In their longitudinal study, Flauri and Buchanan found that the presence of a father in the life of a 16-year-old helps him deal with and cope with the stress he faces around the age of 30 years [20]. Several studies have also highlighted the positive relationship between adolescent self-esteem and the presence of their father in their life [21, 22]. The presence and involvement of a father in the life of adolescents is an important factor in their development, and the lack of a father figure has specific implications for young people [23].

Based on the previous review, the primary objective of the current study is to validate the NFS developed by Finley and Schwartz [16] in the context of Indonesian adolescents. Overall, the need for the current study builds on previous research showing that an adolescent’s perception of whether or not their father accepts them has an impact on their emotional, psychological, and behavioral development [24]. Therefore, it is crucial to acquire a deeper comprehension of the repercussions stemming from the participation of a paternal figure in teenagers within Indonesia. By having a measuring tool that can observe what adolescents feel regarding parenting and the presence of fathers, we will have a better understanding of whether the father's role in parenting is optimal, especially from the child's perspective. This instrument of measurement can also serve as a quantifiable assessment of the extent to which initiatives aimed at enhancing paternal engagement in child-rearing truly yield beneficial outcomes for young individuals in the Indonesian context. In addition, by having a validated measuring tool, knowledge about fathers' parenting, especially in Indonesia, where fathers are not considered the main caregivers, will grow. This makes this research have many benefits.

Materials and Methods

The scale adaptation process uses the flow proposed by Beaton et al. [25]. Before the adaptation stage started, we emailed Finley and Schwartz to ask for permission to adapt the original NFS. Afterward, the initial phase of the scale adaptation procedure involves the process of forward translation, wherein the scale in the original language is linguistically transformed into the desired language. The second stage is carrying out back translation, namely the scale that has been translated into the target language and then is translated back into the original language. The third stage is to carry out a synthesis where a comparison is made between the original scale and the scale resulting from back translation to see whether there is a difference in meaning between the original scale and the translated scale. If there is a difference in meaning, the synthesizer will adjust so that the meaning remains the same. The translation process is carried out by different linguists at each stage. The fourth stage is to provide the translated scale to 2 experts. Experts will assess 4 aspects of equality according to Beaton et al. [25], namely semantic equivalence, idiomatic equivalence, experiential equivalence and conceptual equivalence. Based on the expert’s assessment, a content validity index (CVI) was found. The CVI range of each item was 0.85-1. For the overall CVI results, the score was 0.96. These results indicate that the content validity of the NFS adaptation is quite good. The next stage is to test construct validity by looking at the internal structure of the scale using exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

The data were collected through self-reporting using the NFS. Finley and Schwartz [16] developed this measuring tool in the context of students in America. Accordingly, the NFS produced an adequate fit to the data with one factor (χ2, P<0.001, comparative fit index [CFI]=0.99, root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA]=0.11).

Factor pattern coefficients ranged from 0.50 to 0.85. Meanwhile, the Cronbach α score was 0.94. In this research, the scale was distributed using Google Forms together with an informed consent form. Construct validity was determined for the scale using CFA. CFA is used in situations where a researcher already possesses knowledge and understanding of the dimensions of a scale based on theories and empirical findings from previous studies [26]. The data were tested using the JASP software. The scale consists of eight items ranging from one to five. Each question has a unique answer response, with the numbers by question. The complete items and their responses can be found in the appendices. The total number of respondents to the study was 324 adolescents.

Results

The demographic presented in Table 1 shows that the age range of respondents was between 15 and 18 years, with the majority of respondents being 17 years old (62.9%).

The majority of respondents came from families where both father and mother survived and lived together (86.1%). The gender of the respondents was relatively balanced between men (44.4%) and women (55.6%).

Before evaluating the model, a preliminary examination of the data was performed, using EFA to observe the dispersion of item clusters derived from the scale. Based on the EFA results (Table 2), the items from the NFS were grouped into one factor; accordingly, the NFS was unidimensional.

This is following the original NFS scale designed by Finley and Schwartz. Based on the results of the EFA, the next process is CFA with 1 factor to see the fit model of this measuring instrument.

Factor loading for the eight-item model of the Indonesian version of the NFS for adolescents ranged from 0.808 to 0.947 (Table 3).

Factor loading illustrates the relationship between indicators and latent variables [27]. Brown argued that 0.3 was the minimum limit of factor loading, while Ford stated that 0.4 was the lower limit of factor loading [26, 28]. Based on these calculations, the items of the Indonesian version of the NFA intended for adolescents represent aspects that we wished to measure father nurturance.

The criterion employed to evaluate the appropriateness of the model utilized in the present study was the CFI, which necessitates a minimum value of 0.9 to be regarded as appropriate. Additionally, the Tucker-Lewis index, with an anticipated value exceeding 0.9, is encompassed within the incremental fit indices [27]. The present investigation additionally scrutinized the approximation of the RMSEA, whereby the threshold value is <0.8 and the standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR), with the threshold value being <0.08. Both of these values are encompassed within the absolute fit indices [26, 27, 29]. The chi-square value is anticipated to be greater than 0.05, indicating no discernible distinction between the model and the data [30]. However, the chi-square statistic exhibits a high degree of sensitivity concerning the number of observations. As the sample size increases, the estimation findings tend to become statistically significant. Consequently, the suitability of the model is deemed inadequate; therefore, for the current research, the chi-square values were calculated, but not used as material for the analysis.

A chi-square value was calculated to be <0.001 for the current study (Table 4).

However, due to the susceptibility of chi-square values to the size of the sample, the aforementioned value was not incorporated into the examination of the research study. The study obtained the following values: CFI=0.998, Tucker Lewis index (TLI)=0.998, RMSEA=0.074, SRMR=0.037. Based on the results, the NFS adapted into the Indonesian language is a fit model. Reliability was assessed through the utilization of Cronbach α, yielding a score of 0.938. Furthermore, the range of item-rest correlations was observed to fall within 0.762-0.858 (Table 5).

Discussion

This study examined the validity of the NFS after it had been modified to suit Indonesian adolescents. Through the adaptation process, an eight-item Indonesian-language NFS was standardized for adolescents, finding that the internal structure corresponds to a model fit. item number seven (“overall, how would you rate your father?”) was determined to have the lowest factor loading. However, the range of factor loading for the Indonesian version of the NFS for the context of adolescents was 0.808-0.998, suggesting that all items are capable of illustrating what we intended to measure father nurturance. In addition, based on several fit indices, the Indonesian version of the father nurturance scale was determined to be fit. Accordingly, the scale is suitable for use after adaptation to the Indonesian language and the specific context of adolescents.

The significance of the Indonesian scale’s progress lies in the pivotal role that fathers assume in the advancement of adolescents. Additionally, within patriarchal settings like Indonesia, the engagement of fathers in child-rearing and their active presence in their children’s lives do not arise inherently [31]. The development of an NFS for adolescents in Indonesia can be beneficial in measuring how adolescents perceive their father’s presence in their lives. This information can then be used as a reference for decision-making by relevant institutions, including educational and government institutions [18].

There is an ongoing debate about the reliability of scales that measure concepts retrospectively, such as the NFS, since the results are highly dependent on the respondent’s memory process [18]. However, as Finley and Schwartz argue, retrospective measurements may not be objective, but a person’s subjective perception of their past concerning their father’s presence is more important than objectivity since this perception influences every phase of their development and current state [16]. Meanwhile, the effects of a father’s child-rearing on his offspring endure over time, thus, the creation of this measurement tool has the potential to enhance long-range investigations in the forthcoming years [32].

The present investigation discovered that the adapted iteration of the father nurturance scale in the Indonesian language exhibits commendable internal validity and can be effectively employed for subsequent investigations. However, there are a few ways to make the scale more robust. The validity of the scale should be tested in different population contexts so that its use can be more widespread, and can be used in different research contexts in the future.

Conclusion

The primary aim of this study was to modify NFS for the Indonesian context, with a specific focus on adolescents. This is considered important as previous studies have shown the importance of the father’s role in adolescent development; however, the role of fathers in Indonesia is still not optimal. The findings of this research demonstrated that the NFS instrument, when adjusted to the specific circumstances of Indonesia, exhibits a satisfactory level of reliability, rendering it suitable for application in future investigations. Suggestions for future research are to try to validate NFS in wider cultural contexts and also try to correlate it with other variables.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Ciputra University (Code: 034/EC/KEPK-FKUC/X/2022).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Faculty of Psychology, Airlangga University and the Faculty of Psychology, Ciputra University for supporting this research.

References

- Lamb ME. The history of research on father involvement: An overview. Marriage & Family Review. 2000; 29(2-3):23-42. [DOI:10.1300/J002v29n02_03]

- Bemmelen ST Van. State of the world’s fathers country report: Indonesia 2015. Jakarta: Rutgers WPF Indonesia; 2015. [Link]

- McBride BA, Schoppe SJ, Rane TR. Child characteristics, parenting stress, and parental involvement: Fathers versus mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002; 64(4):998-1011. [DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00998.x]

- Flouri E, Buchanan A. The role of father involvement in children’s later mental health. Journal of Adolescence. 2003; 26(1):63-78. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-1971(02)00116-1] [PMID]

- Magill-Evans J, Harrison MJ. Parent-Child interactions, parenting stress, and developmental outcomes at 4 years. Children’s Health Care. 2001; 30(2):135-50. [Link]

- Brown G, McBride B, Shin N, Bost K. Parenting predictors of father-child attachment security: interactive effects of father involvement and fathering quality. Fathering: A Journal of Theory, Research, and Practice about Men as Fathers. 2007; 5(3):197-219. [Link]

- Flouri E, Midouhas E, Narayanan MK. The relationship between father involvement and child problem behaviour in intact families: A 7-year cross-lagged study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2016; 44(5):1011-21. [DOI:10.1007/s10802-015-0077-9] [PMID]

- Yoon S, Bellamy JL, Kim W, Yoon D. Father involvement and behavior problems among preadolescents at risk of maltreatment. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2018; 27(2):494-504. [DOI:10.1007/s10826-017-0890-6] [PMID]

- Trautmann-Villalba P, Gschwendt M, Schmidt MH, Laucht M. Father-infant interaction patterns as precursors of children’s later externalizing behavior problems: A longitudinal study over 11 years. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2006; 256(6):344-9. [DOI:10.1007/s00406-006-0642-x] [PMID]

- Ramchandani PG, Domoney J, Sethna V, Psychogiou L, Vlachos H, Murray L. Do early father-infant interactions predict the onset of externalising behaviours in young children? Findings from a longitudinal cohort study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013; 54(1):56-64. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02583.x] [PMID]

- Sanjaya EL, Suminar DR, Fardana NA. Father nurturance as moderators of perceived family support for college students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Psychology, Religion, and Humanity. 2021; 3(2):84-94. [DOI:10.32923/psc.v3i2.1844]

- Bosco GL, Renk K, Dinger TM, Epstein MK, Phares V. The connections between adolescents’ perceptions of parents, parental psychological symptoms, and adolescent functioning. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2003; 24(2):179-200. [DOI:10.1016/S0193-3973(03)00044-3]

- Phares V, Fields S, Kamboukos D. Fathers’ and mothers’ involvement with their adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2009; 18(1):1-9. [DOI:10.1007/s10826-008-9200-7]

- Kemenpppa. [Perkuat Peran Ayah Untuk Meningkatkan Kualitas Pengasuhan Anak (Indonesian)] [Internet]. 2020 [Updated 25 May 2023].

- Lamb ME, Pleck JH, Charnov EL, Levine JA. Paternal behavior in humans. American Zoologist. 1985; 25(3):883-94. [DOI:10.1093/icb/25.3.883]

- Finley GE, Schwartz SJ. The father involvement and nurturant fathering scales: Retrospective measures for adolescent and adult children. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2004; 64(1):143-64. [DOI:10.1177/0013164403258453]

- Hawkins A, Bradford K, Palkovitz R, Christiansen S, Day R, Call V. The inventory of father involvement: A pilot study of a new measure of father involvement. The Journal of Men’s Studies. 2002; 10(2):183-96. [DOI:10.3149/jms.1002.183]

- Doyle O, Pecukonis E, Harrington D. The nurturant fathering scale: A confirmatory factor analysis with an african american sample of college students. Research on Social Work Practice. 2011; 21(3):319-27. [DOI:10.1177/1049731510377635]

- Alifa R, Handayani E. The effect of perceived fathers involvement on subjective well-being: Study on early adolescent groups who live without mother In Karawang. Jurnal Psikologi. 2021; 20(2):163-77. [DOI:10.14710/jp.20.2.163-177]

- Flouri E, Buchanan A. Early father’s and mother’s involvement and child’s later educational outcomes. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 2004; 74(2):141-53. [DOI:10.1348/000709904773839806] [PMID]

- Emmanuelle V. Inter-relationships among attachment to mother and father, self-esteem, and career indecision. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2009; 75(2):91-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.jvb.2009.04.007]

- Zia A, Malik AA, Ali SM. Father and daughter relationship and its impact on daughter’s self-esteem and academic achievement. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies. 2015; 4(1):311-6. [DOI:10.5901/mjss.2015.v4n1p311]

- Wagani R. Role of father versus mother in self-esteem of adolescence. Journal of Psychosocial Research. 2019; 13(2):173-82. [Link]

- Khaleque A, Rohner RP. Perceived parental acceptance-rejection and psychological adjustment: A meta-analysis of cross-cultural and intracultural studies. J Marriage and Family. 2002; 64(1):54-64. [DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00054.x]

- Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000; 25(24):3186-91. [DOI:10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014] [PMID]

- Brown TA. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: The Guilford Press; 2015. [Link]

- Wang J, Wang X. Structural equation modeling: Applications using Mplus. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2020. [DOI:10.1002/9781119422730]

- Ford JK, MacCallum RC, Tait M. The application of exploratory factor analysis in applied psychology: A critical review and analysis. Personnel Psychology. 1986; 39(2):291-314.[DOI:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1986.tb00583.x]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press; 2023. [Link]

- Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. LISREL 8: Structural equation modeling with the SIMPLIS command language. Illinois: Scientific Software International; 1993. [Link]

- Seward RR, Stanley-Stevens L. Fathers, fathering, and fatherhood across cultures. In: Selin H, editor. Parenting across cultures. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2014 [DOI:10.1007/978-94-007-7503-9_34]

- Day RD, Lamb ME. Conceptualizing and measuring father involvement. New York: Routledge; 2003. [DOI:10.4324/9781410609380]

Appendix 1.

Indonesian Version of NFS

1. Menurut Anda, seberapa menikmati ayah Anda menjadi menjadi seorang ayah?

_____ sama sekali tidak menikmati

_____ tidak menikmati

_____ terkadang menikmati

_____ menikmati

_____ sangat menikmati

2. Ketika Anda membutuhkan dukungan ayah Anda, apakah dia ada untuk Anda?

_____ tidak pernah ada

_____ jarang ada

_____ terkadang ada

_____ seringkali ada

_____ selalu ada

3. Apakah ayah Anda memiliki cukup energi untuk memenuhi kebutuhan Anda?

_____ tidak pernah

_____ jarang

_____ terkadang

_____ sering

_____ selalu

4. Apakah ayah Anda memiliki waktu untuk dihabiskan berkegiatan bersama Anda?

_____ tidak pernah

_____ jarang

_____ terkadang

_____ sering

_____ selalu

5. Seberapa dekat Anda secara emosional dengan ayah Anda?

_____ tidak pernah

_____ jarang

_____ terkadang

_____ sering

_____ selalu

6. Dalam masa remaja Anda, seberapa akrab Anda dengan ayah Anda?

_____ sangat tidak akrab

_____ tidak akrab

_____ cukup akrab

_____ akrab

_____ sangat akrab

7. Secara keseluruhan, bagaimana Anda menilai ayah Anda

_____ sangat buruk

_____ buruk

_____ cukup

_____ baik

_____ sangat luar biasa

8. Saat Anda menjalani hari Anda, seberapa besar kehadiran psikologis ayah Anda dalam pikiran dan perasaan Anda sehari-hari?

_____ tidak pernah ada

_____ jarang ada

_____ terkadang ada

_____ sering ada

_____ selalu ada

Article type: Original Research Articles |

Subject:

Psychology

Received: 2023/05/27 | Accepted: 2023/10/18 | Published: 2024/09/1

Received: 2023/05/27 | Accepted: 2023/10/18 | Published: 2024/09/1

Send email to the article author