Volume 23, Issue 2 (June 2025)

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2025, 23(2): 209-216 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Uniyal S, Singh D. Mediating Role of Self-compassion Between Cognitive Distortion and Flourishing Among Youth. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2025; 23 (2) :209-216

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2143-en.html

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2143-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, School of Humanities, Gurukula Kangri (Deemed to be University), Haridwar, India.

Full-Text [PDF 477 kb]

(509 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3606 Views)

Full-Text: (294 Views)

Introduction

Mental health issues among youth have become a growing concern in recent years, with researchers constantly highlighting the high prevalence of psychological issues. Cognitive distortion [1], characterized by predictable information processing leading to recognizable inference errors, has been identified as a common cognitive feature associated with various mental disorders. Cognitive biases distort the way individuals perceive the cognitive triad. Dysfunctional subjective constructs are created when different triads of cognitive biases are represented by different means. Human cognitive abilities are paramount and pivotal in understanding diverse situations. Extensive research suggests that cognitive distortion is linked to reduced psychological well-being and increased psychological distress [2], thus having a detrimental impact on mental health outcomes among youth.

Cognitive distortion

The transition period from adolescence to youth brings many challenges and opportunities for personal growth, a critical phase in life. During this developmental phase, youth often face cognitive distortions, such as irrational beliefs and negative self-evaluation, which can hinder their personal growth and well-being. According to the cognitive model, the world delivers people with events that are either negative, positive, or neutral. These events are automatically interpreted through thoughts, evoking specific emotions and moods. Emotions are generated by personal thoughts rather than actual events [3]. Cognitive biases are also part of how people are persuaded to believe untrue things. Therefore, these thoughts amplify negative emotions and thoughts in a person, making them feel rational but exacerbating the situation and making them feel bad about themselves [4]. How we process information also plays a vital role in a person’s emotional responses. According to many cognitive theories of affective disorders, negative information processing can lead to inappropriate behaviors and emotional consequences [5]. Maladaptive emotions arise when individuals interpret events through negative automatic thoughts. These negative automatic thoughts are rooted in cognitive biases originating from negative core beliefs or schemas. Understanding cognitive distortions’ underlying mechanisms, prevalence, and associated outcomes is essential for effective prevention and intervention.

Flourishing

Flourishing in youth refers to positive mental health and optimal functioning in various domains. Understanding the factors contributing to flourishing and well-being is vital for overall development. Flourishing has been recognized as a significant measure of life satisfaction and quality of life following the concept of psychological well-being and authentic happiness introduced by Seligman. Seligman proposed a model of flourishing called the “PERMA” model, consisting of five components: Positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and achievement [6]. Research on flourishing also demonstrated that flourishing leads to improved emotional strength, which helps to accept self-criticism and self-judgment [7]. Flourishing also refers to optimal mental health characterized by social, psychological, and emotional well-being [8]. Research suggests that flourishing is associated with various positive factors. Catalino and Fredrickson [9] have shown that flourishing is connected to positive emotional responsiveness and mindfulness. Additionally, it is linked to vitality, self-determination, personal growth, meaningful relationships, and fewer constraints on daily activities. Furthermore, positive emotions are vital for physical and psychological health, cognitive performance, and productivity [10]. Engaging in meaningful pursuits that bring fulfillment and enjoyment empowers individuals to actualize their potential to the fullest extent. Nurturing satisfying interpersonal connections significantly enhances one’s sense of happiness and overall welfare. Additionally, a sense of meaning is a significant dimension of flourishing, where individuals find purpose and direction in their lives by pursuing meaningful goals [11].

Self-compassion

Self-compassion refers to how we perceive and treat ourselves when faced with failure, inadequacy, and personal distress. Initially, as introduced by Neff [12], the concept of self-compassion was inspired by the broader notion of compassion for others in Buddhist philosophy [13]. According to Buddhism, compassion is all-encompassing and includes both oneself and others. Examining the overall experience of compassion is helpful to grasp the meaning of self-compassion. Goetz et al. [14] defined compassion as an emotion that arises when we witness someone else’s suffering and feel compelled to help them. This emotion is characterized by warmth and care rather than cold judgment and is driven by a desire to assist rather than harm. Self-compassion manifests in two distinct ways, each serving a different purpose. First, it can be gentle and nurturing, mainly towards self-acceptance and comforting ourselves during emotional distress. Second, it can be strong and assertive, mainly when focused on self-protection, fulfilling essential needs, or motivating personal growth and transformation [15]. Numerous studies have consistently demonstrated a strong relationship between higher levels of self-compassion and decreased psychopathological symptoms. Several meta-analyses examining diverse adult and adolescent populations have reported significant relationships between self-compassion and various negative mental states, including depression, anxiety, stress, and suicidal thoughts [16, 17]. Longitudinal research conducted by Stutts et al. [18] found that baseline levels of self-compassion predicted lower levels of depression, anxiety, and negative emotions after six months. Additionally, Lee [19] discovered that an increase in self-compassion over five years was associated with reduced psychopathology and decreased feelings of loneliness. Self-compassion mitigates psychopathology through various mechanisms. One critical mechanism involves reducing automatic and negative irrational thought patterns. Furthermore, self-compassion is associated with decreased avoidance of negative emotions [20], reduced entanglement with negative emotions [21], and improved emotion regulation skills [22]. Studies suggest that self-compassion positively impacts mental states by reducing negative emotions and fostering positive ones. For instance, in a longitudinal study, participants who wrote self-compassionate letters to themselves for five consecutive days experienced a decrease in depression levels for three months and an increase in happiness for six months [23].

Rationale for current study

This study examined the relationship between cognitive distortion, flourishing, and self-compassion. We hypothesized that cognitive distortion would be negatively correlated with flourishing and self-compassion, while flourishing would be positively correlated. Various researchers have suggested self-compassion as an adaptive coping strategy for psychological issues. Self-compassion has been recognized as a beneficial factor in promoting enhanced well-being. While previous studies have explored the relationship between cognitive distortions and self-compassion, none have investigated how self-compassion mediates the relationship between cognitive distortions and flourishing. The prevalence of cognitive distortion among youth affects their thought processes in each domain of their lives, leading to a negative effect on mental health. This study will also enhance our understanding of mitigating cognitive distortions’ negative impact and the thought processes associated with promoting flourishing. Understanding these mechanisms related to the mediating role of self-compassion can provide valuable insights into developing targeted interventions related to self-compassion, which can help encourage better mental health outcomes in youth facing cognitive distortions. Also, it hypothesized that self-compassion would mediate the relationship between cognitive distortion and flourishing.

Objectives

This study aims to investigate the mediating role of self-compassion in the relationship between cognitive distortion and flourishing among Indian youth.

Materials and Methods

Research design

This study used a cross-sectional research design to examine the mediating role of self-compassion in the relationship between cognitive distortion and flourishing.

Participants and procedure

The sample in the present study consisted of university students aged 18-24 years (Mean±SD, 21.5±1.41) through random sampling. The study involved 250 students recruited from different tertiary educational institutions in Uttarakhand, India. Participants were included in the study if they understood English. Following a comprehensive inspection, incomplete or improperly filled questionnaires were excluded. After exclusion, 221 participants remained in the study. The online survey was conducted by creating a Google form, and the link to the survey form was shared on different online platforms. Participants were provided with an information sheet, outlining the research goal when they first accessed the survey. The confidentiality of their responses and their right to withdraw from the research were explained to the participants. Participants then provided informed consent and completed the measures in an online format. The survey took approximately 15 minutes to complete.

Measures scales

The scales related to each construct were taken from their respective validated scales to measure the study’s variables. Permission was obtained from all the authors of the respective scales, and they were used in the study.

Cognitive distortion scale (CDS)

The 40-item CDS [24] measures cognitive distortions, biased or unreasonable thought processes. The CDS identifies and quantifies the presence and severity of these distortions. The measure consists of five subscales meant to assess distinct elements of cognitive distortion associated with traumatic events: Self-blame, self-criticism, helplessness, hopelessness, and concern about risk. Respondents scored their agreement with each statement using a Likert scale ranging from 1 (“never”) to 5 (indicating “very often”). This evaluation allows individuals to indicate how much they display cognitive distortions. Each dimension contains eight items. The total score on the CDS is between 40 and 200, reflecting the overall level of cognitive distortion, with a higher score indicating a higher prevalence of distorted thinking patterns. The CDS has well-established reliability (0.89) and validity (0.94) and has been widely used.

Flourishing scale (FS)

The FS [25] is an 8-item assessment tool for evaluating social-psychological well-being. It gauges various aspects of well-being, such as the perception of leading a purposeful and meaningful life. Respondents on a 7-point Likert scale assess their agreement with each statement from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Higher scores on the scale, which has a total score range of 8-56, indicate a higher level of well-being. The FS demonstrated great reliability in the initial validation research conducted by Diener et al. [25] with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.87.

Self-compassion scale (SCS)

The SCS [26] is a 26-item questionnaire that measures self-compassion. It is divided into six parts: “Self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification.” Each subscale comprises several statements that people score on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (nearly never) to 5 (almost often). The self-judgment, isolation, and mindfulness subscales are reverse-scored to determine the total self-compassion score. Individual scores on each subscale are then summed, yielding an overall scale mean ranging from 1 to 5. Higher mean scores suggest greater self-compassion. The SCS exhibited great reliability in the initial study by Neff, with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.92.

Data analysis

IBM SPSS software, version 23 was used for the statistical analysis. Initially, Q-Q plots were used to check the data for outliers, and the neutralization approach imputed approximately 0.7% of the data. Furthermore, Garson’s criterion verified the data’s normality. The kurtosis and skewness values were below Garson’s range of -2.00 to +2.00. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were used to perform the correlations. The mediation analysis utilized the Process Macro (Hayes, 2017) [26], which employs bootstrap confidence intervals to estimate indirect effects. In the model analysis, 5000 bootstrap samples were analyzed. The 95% biased-corrected confidence intervals were used to determine significant effects. Essentially, a mediated effect is thought to exist if a zero value does not exist between the confidence interval’s lower and upper bound range.

Results

Descriptive statistics

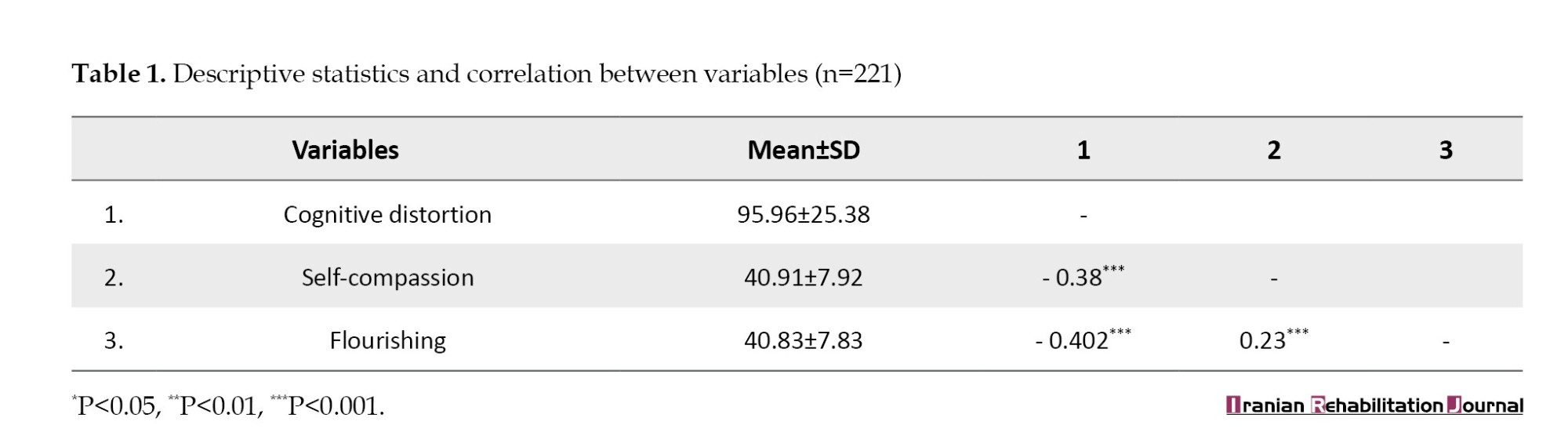

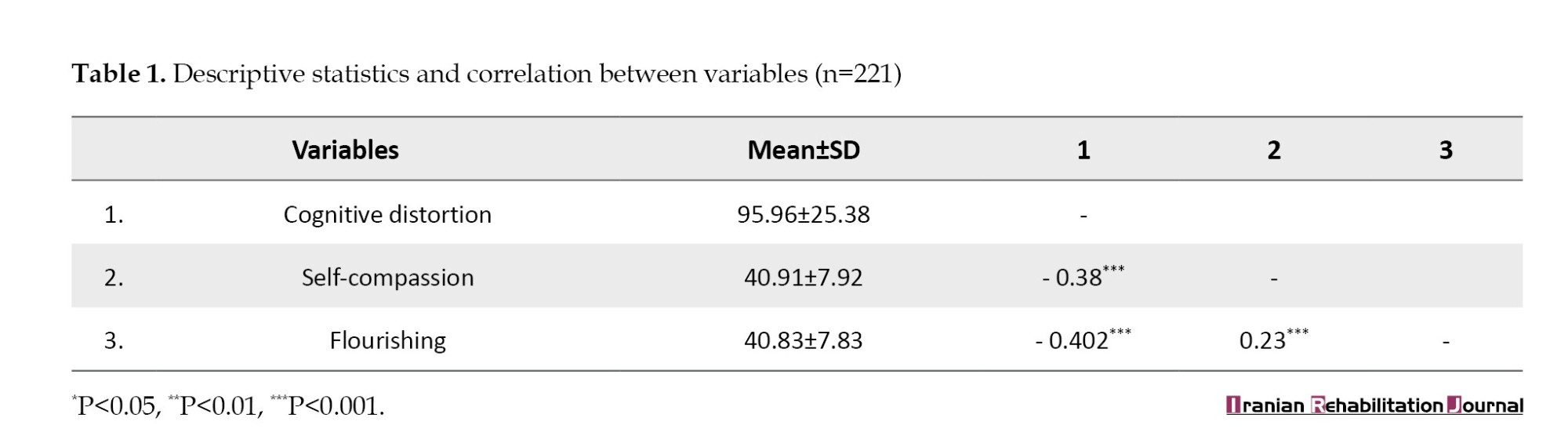

Table 1 presents the Mean±SD and the intercorrelations among the variables. As depicted in Table 1, cognitive distortion exhibited negative correlations with self-compassion (-0.38) and flourishing (-0.42). Conversely, self-compassion was positively correlated with flourishing (0.23). These results satisfy the conditions outlined by Baron and Kenny for testing a mediation effect: significant relationships between the predictor (cognitive distortion) and the mediator (self-compassion), the mediator (self-compassion) and the outcome (flourishing), and the predictor (cognitive distortion) and the outcome (flourishing).

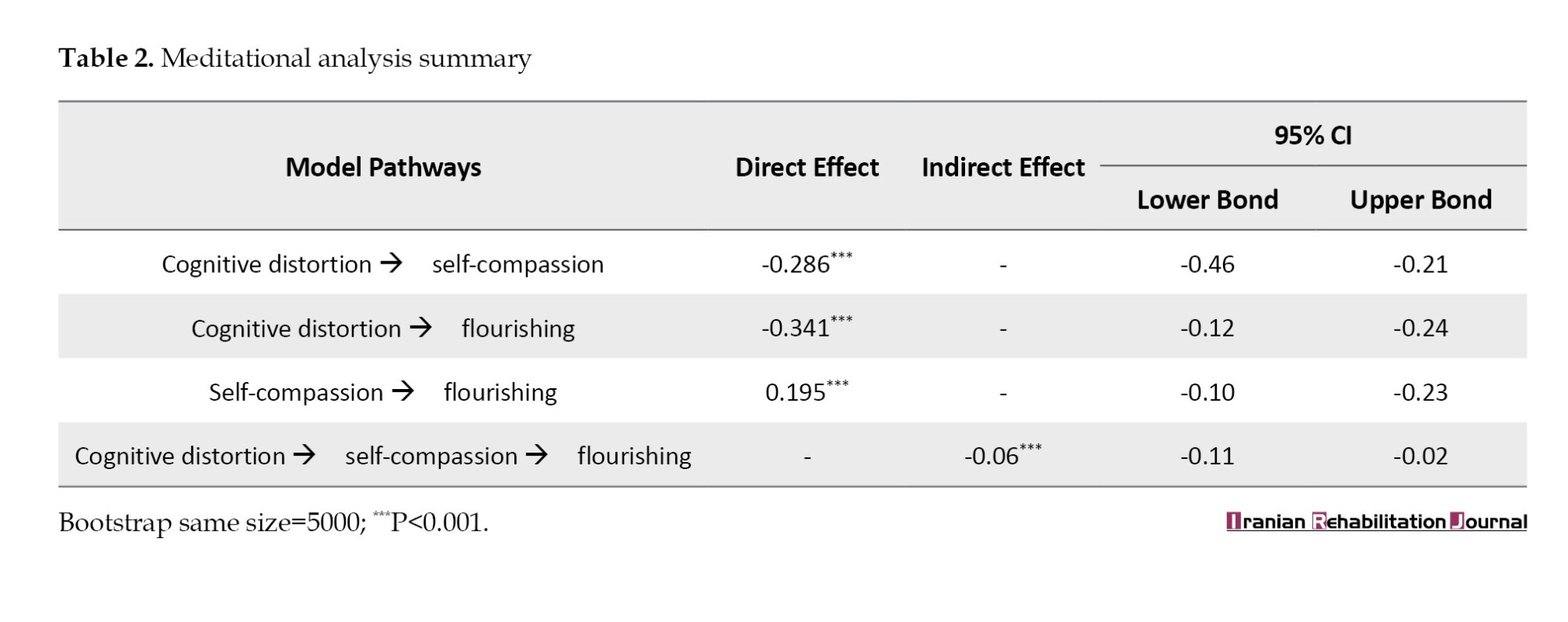

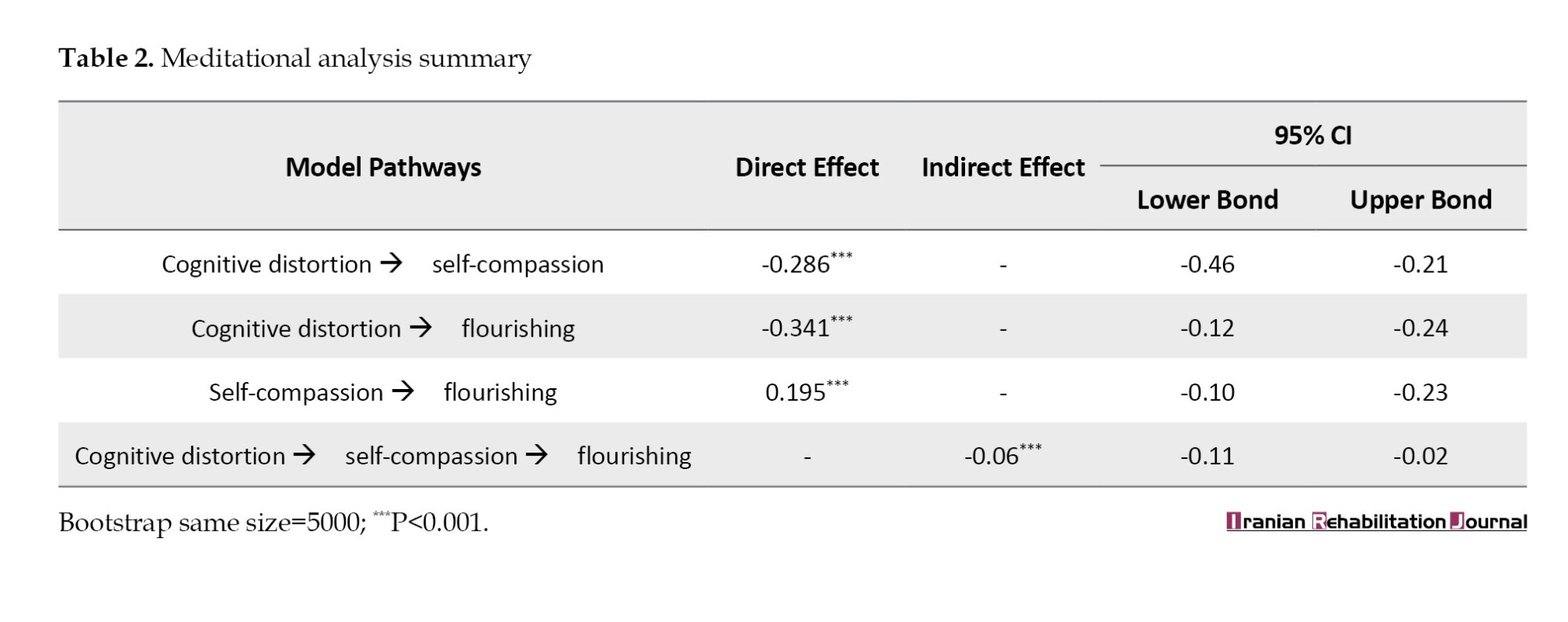

Preacher and Hayes [27] utilized a mediation approach to analyze the model. This non-parametric bootstrapping technique offers statistically robust and precise results compared to traditional methods of meditation modeling. The results indicated a significant indirect effect of cognitive distortion on flourishing through self-compassion (β=-0.06, 95% Confidence Interval (CI), -0.11%, -0.02%, P<0.001). Additionally, a significant direct effect of cognitive distortion on flourishing was observed even in the presence of the mediator (β=-0.341, 95% CI, -0.12%, -0.24%, P<0.001). Therefore, it can be concluded that self-compassion partially mediates the relationship between cognitive distortion and flourishing. Furthermore, since (a×b×c) is positive, it suggests that self-compassion plays a complementary partial mediation role in the mentioned relationship. Table 2 presents the mediation analysis.

Discussion

In this study, a meditational model was developed to elucidate the mechanism underlying the relationship between cognitive distortion and flourishing among young individuals. Our results offer insights into how cognitive distortion predicts lower levels of flourishing. As anticipated, the results revealed a mediating role of self-compassion in the relationship between cognitive distortion and flourishing. Particularly, our direct approach confirms that cognitive distortion is inversely linked to flourishing, consistent with prior research results [28]. The results suggest that cognitive distortion harms the mental well-being of individuals with early adverse irrational beliefs. High levels of self-compassion seem to mitigate the influence of irrational thoughts, as individuals with such traits tend to approach self-related information with openness and flexibility, potentially alleviating psychological and behavioral issues that contribute to psychological distress. Moreover, prior research [29] demonstrated a negative correlation between cognitive distortion and self-compassion among young individuals. The indirect effect model revealed that even with self-compassion in the relationship, the direct effect of cognitive distortion on flourishing remained significant. These results further support previous research indicating that enhancing self-compassion is linked to enhanced flourishing and psychological well-being [30]. Furthermore, self-compassion may serve as a pivotal mechanism underlying the therapeutic effectiveness of reappraisal in fostering positive psychological outcomes. Therefore, individuals with higher levels of self-compassion may experience less psychological distress than those with adverse cognitive distortions and lower self-compassion. Research has established that self-compassion mediates various theories elucidating stress and depression, such as the association between mindfulness and anxiety, the connection between college students’ unhealthy perfectionism and symptoms of depression, and the relationship between self-stigma and depression [31]. However, the mediating role of self-compassion in the relationship between cognitive distortion and flourishing has not yet been explored. Therefore, these results offer additional empirical evidence supporting the protective function of self-compassion against irrational thought patterns, as proposed by Neff [12]. Individuals who show kindness and understanding tend to have higher self-esteem than those who do not. As expected, the strong association between self-compassion and thriving confirms Neff’s hypothesis [15]. Additionally, self-compassion was identified as a partial mediator, suggesting the existence of other variables that could further explain the relationship between cognitive distortion and flourishing. However, individuals who demonstrate self-compassion may be more adept at treating themselves kindly than those who do not. Consequently, they may respond less harshly to negative thoughts, feeling more confident in addressing erroneous beliefs. Our results support integrating self-compassion training into psychological interventions for individuals with irrational thoughts. Self-compassion training has been utilized in various intervention models by psychologists working with individuals facing psychological distress, and has been demonstrated to be effective.

Implications

The results show that self-compassion can serve as a protective factor in alleviating the impact of cognitive distortions among young individuals. This suggests a potential benefit of targeting interventions to enhance self-compassion to improve youth’s psychological well-being and flourishing. Given that cognitive biases can influence various aspects of their lives, including development, education, employment, and relationships, universities can play a significant role in offering opportunities to reach out to youth during this critical transitional period. Many universities provide counseling services or support groups that could serve as platforms for introducing self-compassion programs and interventions. These initiatives can help individuals cultivate a healthy mindset and adaptive coping mechanisms during challenging events. Moreover, previous research on self-compassion interventions has yielded promising results in general [32] and in clinical populations [33]. Also, social media can provide an opportunity to reach out to youth, creating awareness programs, workshops, and seminars about the importance of self-compassion and its protective benefits. Thus, including these programs and interventions can help the youth population with cognitive distortions and improve their mental health outcomes.

Further directions for researchers

These results do not suggest that self-compassion is the sole mediating factor in the relationship between cognitive distortions and flourishing; other variables likely explain this relationship. Moreover, since self-report measures were utilized, future research could benefit from adopting an experimental and longitudinal approach to assess the effectiveness of self-compassion interventions in promoting positive mental health. Additionally, exploring multiple mediators alongside self-compassion could elucidate their combined impact on psychological well-being.

Conclusion

The present study proves that self-compassion partially mediates the relationship between cognitive distortion and flourishing. This discovery has implications for future research on acquiring and applying self-compassion techniques. It is imperative to conduct further research to validate these results and expand them through controlled empirical investigations testing the effectiveness of self-compassion training in enhancing counselors’ self–other compassion. Moreover, for self-compassion to be confidently integrated into counseling and educational practices, researchers must demonstrate that such training improves counselor performance (e.g. by enhancing the therapeutic relationship, empathy, and compassion for clients) and, importantly, client outcomes. Finally, the potential influence of demographic variables, such as gender, income, or religious beliefs on participants’ levels of self-compassion or flourishing was not examined in this study. Therefore, future studies should investigate whether these demographic factors suppress study variables.

Limitations

The current study employed a cross-sectional and correlational design, precluding any causal inferences. Additionally, using self-reporting tools, which assess trends rather than present states, introduces the potential for bias. Furthermore, these tools do not consider the influence of other variables. These limitations also apply to mediation models that rely on correlation pathways.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Gurukula Kangri (Deemed to be University), Haridwar, India (Code: IEC/GKDBTU/1009). Participants were provided with a clear explanation of the study’s purpose and procedures. Additionally, they were assured of their data’s confidentiality and freedom to withdraw from the study. Written consent was obtained from all participants, and the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration were strictly followed.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their special thanks to all participants in the study.

References

Mental health issues among youth have become a growing concern in recent years, with researchers constantly highlighting the high prevalence of psychological issues. Cognitive distortion [1], characterized by predictable information processing leading to recognizable inference errors, has been identified as a common cognitive feature associated with various mental disorders. Cognitive biases distort the way individuals perceive the cognitive triad. Dysfunctional subjective constructs are created when different triads of cognitive biases are represented by different means. Human cognitive abilities are paramount and pivotal in understanding diverse situations. Extensive research suggests that cognitive distortion is linked to reduced psychological well-being and increased psychological distress [2], thus having a detrimental impact on mental health outcomes among youth.

Cognitive distortion

The transition period from adolescence to youth brings many challenges and opportunities for personal growth, a critical phase in life. During this developmental phase, youth often face cognitive distortions, such as irrational beliefs and negative self-evaluation, which can hinder their personal growth and well-being. According to the cognitive model, the world delivers people with events that are either negative, positive, or neutral. These events are automatically interpreted through thoughts, evoking specific emotions and moods. Emotions are generated by personal thoughts rather than actual events [3]. Cognitive biases are also part of how people are persuaded to believe untrue things. Therefore, these thoughts amplify negative emotions and thoughts in a person, making them feel rational but exacerbating the situation and making them feel bad about themselves [4]. How we process information also plays a vital role in a person’s emotional responses. According to many cognitive theories of affective disorders, negative information processing can lead to inappropriate behaviors and emotional consequences [5]. Maladaptive emotions arise when individuals interpret events through negative automatic thoughts. These negative automatic thoughts are rooted in cognitive biases originating from negative core beliefs or schemas. Understanding cognitive distortions’ underlying mechanisms, prevalence, and associated outcomes is essential for effective prevention and intervention.

Flourishing

Flourishing in youth refers to positive mental health and optimal functioning in various domains. Understanding the factors contributing to flourishing and well-being is vital for overall development. Flourishing has been recognized as a significant measure of life satisfaction and quality of life following the concept of psychological well-being and authentic happiness introduced by Seligman. Seligman proposed a model of flourishing called the “PERMA” model, consisting of five components: Positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and achievement [6]. Research on flourishing also demonstrated that flourishing leads to improved emotional strength, which helps to accept self-criticism and self-judgment [7]. Flourishing also refers to optimal mental health characterized by social, psychological, and emotional well-being [8]. Research suggests that flourishing is associated with various positive factors. Catalino and Fredrickson [9] have shown that flourishing is connected to positive emotional responsiveness and mindfulness. Additionally, it is linked to vitality, self-determination, personal growth, meaningful relationships, and fewer constraints on daily activities. Furthermore, positive emotions are vital for physical and psychological health, cognitive performance, and productivity [10]. Engaging in meaningful pursuits that bring fulfillment and enjoyment empowers individuals to actualize their potential to the fullest extent. Nurturing satisfying interpersonal connections significantly enhances one’s sense of happiness and overall welfare. Additionally, a sense of meaning is a significant dimension of flourishing, where individuals find purpose and direction in their lives by pursuing meaningful goals [11].

Self-compassion

Self-compassion refers to how we perceive and treat ourselves when faced with failure, inadequacy, and personal distress. Initially, as introduced by Neff [12], the concept of self-compassion was inspired by the broader notion of compassion for others in Buddhist philosophy [13]. According to Buddhism, compassion is all-encompassing and includes both oneself and others. Examining the overall experience of compassion is helpful to grasp the meaning of self-compassion. Goetz et al. [14] defined compassion as an emotion that arises when we witness someone else’s suffering and feel compelled to help them. This emotion is characterized by warmth and care rather than cold judgment and is driven by a desire to assist rather than harm. Self-compassion manifests in two distinct ways, each serving a different purpose. First, it can be gentle and nurturing, mainly towards self-acceptance and comforting ourselves during emotional distress. Second, it can be strong and assertive, mainly when focused on self-protection, fulfilling essential needs, or motivating personal growth and transformation [15]. Numerous studies have consistently demonstrated a strong relationship between higher levels of self-compassion and decreased psychopathological symptoms. Several meta-analyses examining diverse adult and adolescent populations have reported significant relationships between self-compassion and various negative mental states, including depression, anxiety, stress, and suicidal thoughts [16, 17]. Longitudinal research conducted by Stutts et al. [18] found that baseline levels of self-compassion predicted lower levels of depression, anxiety, and negative emotions after six months. Additionally, Lee [19] discovered that an increase in self-compassion over five years was associated with reduced psychopathology and decreased feelings of loneliness. Self-compassion mitigates psychopathology through various mechanisms. One critical mechanism involves reducing automatic and negative irrational thought patterns. Furthermore, self-compassion is associated with decreased avoidance of negative emotions [20], reduced entanglement with negative emotions [21], and improved emotion regulation skills [22]. Studies suggest that self-compassion positively impacts mental states by reducing negative emotions and fostering positive ones. For instance, in a longitudinal study, participants who wrote self-compassionate letters to themselves for five consecutive days experienced a decrease in depression levels for three months and an increase in happiness for six months [23].

Rationale for current study

This study examined the relationship between cognitive distortion, flourishing, and self-compassion. We hypothesized that cognitive distortion would be negatively correlated with flourishing and self-compassion, while flourishing would be positively correlated. Various researchers have suggested self-compassion as an adaptive coping strategy for psychological issues. Self-compassion has been recognized as a beneficial factor in promoting enhanced well-being. While previous studies have explored the relationship between cognitive distortions and self-compassion, none have investigated how self-compassion mediates the relationship between cognitive distortions and flourishing. The prevalence of cognitive distortion among youth affects their thought processes in each domain of their lives, leading to a negative effect on mental health. This study will also enhance our understanding of mitigating cognitive distortions’ negative impact and the thought processes associated with promoting flourishing. Understanding these mechanisms related to the mediating role of self-compassion can provide valuable insights into developing targeted interventions related to self-compassion, which can help encourage better mental health outcomes in youth facing cognitive distortions. Also, it hypothesized that self-compassion would mediate the relationship between cognitive distortion and flourishing.

Objectives

This study aims to investigate the mediating role of self-compassion in the relationship between cognitive distortion and flourishing among Indian youth.

Materials and Methods

Research design

This study used a cross-sectional research design to examine the mediating role of self-compassion in the relationship between cognitive distortion and flourishing.

Participants and procedure

The sample in the present study consisted of university students aged 18-24 years (Mean±SD, 21.5±1.41) through random sampling. The study involved 250 students recruited from different tertiary educational institutions in Uttarakhand, India. Participants were included in the study if they understood English. Following a comprehensive inspection, incomplete or improperly filled questionnaires were excluded. After exclusion, 221 participants remained in the study. The online survey was conducted by creating a Google form, and the link to the survey form was shared on different online platforms. Participants were provided with an information sheet, outlining the research goal when they first accessed the survey. The confidentiality of their responses and their right to withdraw from the research were explained to the participants. Participants then provided informed consent and completed the measures in an online format. The survey took approximately 15 minutes to complete.

Measures scales

The scales related to each construct were taken from their respective validated scales to measure the study’s variables. Permission was obtained from all the authors of the respective scales, and they were used in the study.

Cognitive distortion scale (CDS)

The 40-item CDS [24] measures cognitive distortions, biased or unreasonable thought processes. The CDS identifies and quantifies the presence and severity of these distortions. The measure consists of five subscales meant to assess distinct elements of cognitive distortion associated with traumatic events: Self-blame, self-criticism, helplessness, hopelessness, and concern about risk. Respondents scored their agreement with each statement using a Likert scale ranging from 1 (“never”) to 5 (indicating “very often”). This evaluation allows individuals to indicate how much they display cognitive distortions. Each dimension contains eight items. The total score on the CDS is between 40 and 200, reflecting the overall level of cognitive distortion, with a higher score indicating a higher prevalence of distorted thinking patterns. The CDS has well-established reliability (0.89) and validity (0.94) and has been widely used.

Flourishing scale (FS)

The FS [25] is an 8-item assessment tool for evaluating social-psychological well-being. It gauges various aspects of well-being, such as the perception of leading a purposeful and meaningful life. Respondents on a 7-point Likert scale assess their agreement with each statement from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Higher scores on the scale, which has a total score range of 8-56, indicate a higher level of well-being. The FS demonstrated great reliability in the initial validation research conducted by Diener et al. [25] with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.87.

Self-compassion scale (SCS)

The SCS [26] is a 26-item questionnaire that measures self-compassion. It is divided into six parts: “Self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification.” Each subscale comprises several statements that people score on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (nearly never) to 5 (almost often). The self-judgment, isolation, and mindfulness subscales are reverse-scored to determine the total self-compassion score. Individual scores on each subscale are then summed, yielding an overall scale mean ranging from 1 to 5. Higher mean scores suggest greater self-compassion. The SCS exhibited great reliability in the initial study by Neff, with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.92.

Data analysis

IBM SPSS software, version 23 was used for the statistical analysis. Initially, Q-Q plots were used to check the data for outliers, and the neutralization approach imputed approximately 0.7% of the data. Furthermore, Garson’s criterion verified the data’s normality. The kurtosis and skewness values were below Garson’s range of -2.00 to +2.00. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were used to perform the correlations. The mediation analysis utilized the Process Macro (Hayes, 2017) [26], which employs bootstrap confidence intervals to estimate indirect effects. In the model analysis, 5000 bootstrap samples were analyzed. The 95% biased-corrected confidence intervals were used to determine significant effects. Essentially, a mediated effect is thought to exist if a zero value does not exist between the confidence interval’s lower and upper bound range.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents the Mean±SD and the intercorrelations among the variables. As depicted in Table 1, cognitive distortion exhibited negative correlations with self-compassion (-0.38) and flourishing (-0.42). Conversely, self-compassion was positively correlated with flourishing (0.23). These results satisfy the conditions outlined by Baron and Kenny for testing a mediation effect: significant relationships between the predictor (cognitive distortion) and the mediator (self-compassion), the mediator (self-compassion) and the outcome (flourishing), and the predictor (cognitive distortion) and the outcome (flourishing).

Preacher and Hayes [27] utilized a mediation approach to analyze the model. This non-parametric bootstrapping technique offers statistically robust and precise results compared to traditional methods of meditation modeling. The results indicated a significant indirect effect of cognitive distortion on flourishing through self-compassion (β=-0.06, 95% Confidence Interval (CI), -0.11%, -0.02%, P<0.001). Additionally, a significant direct effect of cognitive distortion on flourishing was observed even in the presence of the mediator (β=-0.341, 95% CI, -0.12%, -0.24%, P<0.001). Therefore, it can be concluded that self-compassion partially mediates the relationship between cognitive distortion and flourishing. Furthermore, since (a×b×c) is positive, it suggests that self-compassion plays a complementary partial mediation role in the mentioned relationship. Table 2 presents the mediation analysis.

Discussion

In this study, a meditational model was developed to elucidate the mechanism underlying the relationship between cognitive distortion and flourishing among young individuals. Our results offer insights into how cognitive distortion predicts lower levels of flourishing. As anticipated, the results revealed a mediating role of self-compassion in the relationship between cognitive distortion and flourishing. Particularly, our direct approach confirms that cognitive distortion is inversely linked to flourishing, consistent with prior research results [28]. The results suggest that cognitive distortion harms the mental well-being of individuals with early adverse irrational beliefs. High levels of self-compassion seem to mitigate the influence of irrational thoughts, as individuals with such traits tend to approach self-related information with openness and flexibility, potentially alleviating psychological and behavioral issues that contribute to psychological distress. Moreover, prior research [29] demonstrated a negative correlation between cognitive distortion and self-compassion among young individuals. The indirect effect model revealed that even with self-compassion in the relationship, the direct effect of cognitive distortion on flourishing remained significant. These results further support previous research indicating that enhancing self-compassion is linked to enhanced flourishing and psychological well-being [30]. Furthermore, self-compassion may serve as a pivotal mechanism underlying the therapeutic effectiveness of reappraisal in fostering positive psychological outcomes. Therefore, individuals with higher levels of self-compassion may experience less psychological distress than those with adverse cognitive distortions and lower self-compassion. Research has established that self-compassion mediates various theories elucidating stress and depression, such as the association between mindfulness and anxiety, the connection between college students’ unhealthy perfectionism and symptoms of depression, and the relationship between self-stigma and depression [31]. However, the mediating role of self-compassion in the relationship between cognitive distortion and flourishing has not yet been explored. Therefore, these results offer additional empirical evidence supporting the protective function of self-compassion against irrational thought patterns, as proposed by Neff [12]. Individuals who show kindness and understanding tend to have higher self-esteem than those who do not. As expected, the strong association between self-compassion and thriving confirms Neff’s hypothesis [15]. Additionally, self-compassion was identified as a partial mediator, suggesting the existence of other variables that could further explain the relationship between cognitive distortion and flourishing. However, individuals who demonstrate self-compassion may be more adept at treating themselves kindly than those who do not. Consequently, they may respond less harshly to negative thoughts, feeling more confident in addressing erroneous beliefs. Our results support integrating self-compassion training into psychological interventions for individuals with irrational thoughts. Self-compassion training has been utilized in various intervention models by psychologists working with individuals facing psychological distress, and has been demonstrated to be effective.

Implications

The results show that self-compassion can serve as a protective factor in alleviating the impact of cognitive distortions among young individuals. This suggests a potential benefit of targeting interventions to enhance self-compassion to improve youth’s psychological well-being and flourishing. Given that cognitive biases can influence various aspects of their lives, including development, education, employment, and relationships, universities can play a significant role in offering opportunities to reach out to youth during this critical transitional period. Many universities provide counseling services or support groups that could serve as platforms for introducing self-compassion programs and interventions. These initiatives can help individuals cultivate a healthy mindset and adaptive coping mechanisms during challenging events. Moreover, previous research on self-compassion interventions has yielded promising results in general [32] and in clinical populations [33]. Also, social media can provide an opportunity to reach out to youth, creating awareness programs, workshops, and seminars about the importance of self-compassion and its protective benefits. Thus, including these programs and interventions can help the youth population with cognitive distortions and improve their mental health outcomes.

Further directions for researchers

These results do not suggest that self-compassion is the sole mediating factor in the relationship between cognitive distortions and flourishing; other variables likely explain this relationship. Moreover, since self-report measures were utilized, future research could benefit from adopting an experimental and longitudinal approach to assess the effectiveness of self-compassion interventions in promoting positive mental health. Additionally, exploring multiple mediators alongside self-compassion could elucidate their combined impact on psychological well-being.

Conclusion

The present study proves that self-compassion partially mediates the relationship between cognitive distortion and flourishing. This discovery has implications for future research on acquiring and applying self-compassion techniques. It is imperative to conduct further research to validate these results and expand them through controlled empirical investigations testing the effectiveness of self-compassion training in enhancing counselors’ self–other compassion. Moreover, for self-compassion to be confidently integrated into counseling and educational practices, researchers must demonstrate that such training improves counselor performance (e.g. by enhancing the therapeutic relationship, empathy, and compassion for clients) and, importantly, client outcomes. Finally, the potential influence of demographic variables, such as gender, income, or religious beliefs on participants’ levels of self-compassion or flourishing was not examined in this study. Therefore, future studies should investigate whether these demographic factors suppress study variables.

Limitations

The current study employed a cross-sectional and correlational design, precluding any causal inferences. Additionally, using self-reporting tools, which assess trends rather than present states, introduces the potential for bias. Furthermore, these tools do not consider the influence of other variables. These limitations also apply to mediation models that rely on correlation pathways.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Gurukula Kangri (Deemed to be University), Haridwar, India (Code: IEC/GKDBTU/1009). Participants were provided with a clear explanation of the study’s purpose and procedures. Additionally, they were assured of their data’s confidentiality and freedom to withdraw from the study. Written consent was obtained from all participants, and the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration were strictly followed.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their special thanks to all participants in the study.

References

- Beck AT. Depression: Clinical, experimental, and theoretical aspects. The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 1969; 18(87):249. [Link]

- Faustino B, Vasco AB, Silva AN, Marques T. Relationships between emotional schemas, mindfulness, self-compassion and unconditional self-acceptance on the regulation of psychological needs. Research in Psychotherapy. 2020; 23(2):442. [DOI:10.4081/ripppo.2020.442] [PMID]

- Burns DD. Feeling good. New York: HarperCollins; 2008.

- McGrath EP, Repetti RL. A longitudinal study of children’s depressive symptoms, self-perceptions, and cognitive distortions about the self. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002; 111(1):77-87. [DOI:10.1037/0021-843X.111.1.77] [PMID]

- Dozois DJ, Bieling PJ, Patelis-Siotis I, Hoar L, Chudzik S, McCabe K, et al. Changes in self-schema structure in cognitive therapy for major depressive disorder: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009; 77(6):1078-88. [DOI:10.1037/a0016886] [PMID]

- Seligman MEP. Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York: Simon Element / Simon Acumen; 2011. [Link]

- Jafari F. The mediating role of self- compassion in relation between character strengths and flourishing in college students. International Journal of Happiness and Development. 2020; 6(1):76-93. [DOI:10.1504/IJHD.2020.108755]

- Stoeber J, Corr PJ. A short empirical note on perfectionism and flourishing. Personality and Individual Differences. 2016; 90:50-3. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2015.10.036]

- Catalino LI, Fredrickson BL. A Tuesday in the life of a flourisher: The role of positive emotional reactivity in optimal mental health. Emotion. 2011; 11(4):938-50. [DOI:10.1037/a0024889] [PMID]

- Huppert F. Psychological Well-being: Evidence Regarding its Causes and Consequences. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-being. 2009; 1(2):137-64. [DOI:10.1111/j.1758-0854.2009.01008.x]

- Jacobsen B. Invitation to existential psychology: A psychology for the unique human being and its applications in therapy. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2008. [DOI:10.1002/9780470773222]

- Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity. 2003; 2(3):223-50.[Link]

- Brach T. Radical Acceptance: Embracing Your Life With the Heart of a Buddha. New York: Random House Publishing Group; 2004. [Link]

- Goetz JL, Keltner D, Simon-Thomas E. Compassion: An evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin. 2010; 136(3):351-74. [DOI:10.1037/a0018807] [PMID]

- Neff K. Fierce self-compassion: How women can harness kindness to speak up, claim their power, and thrive. UK: Penguin; 2021. [Link]

- Bluth K, Blanton PW. Mindfulness and Self-Compassion: Exploring pathways to adolescent emotional well-Being. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2014; 23(7):1298-309. [DOI:10.1007/s10826-013-9830-2] [PMID]

- Suh H, Jeong J. Association of self-compassion with suicidal thoughts and behaviors and non-suicidal self injury: A Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021; 12:633482. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.633482] [PMID]

- Stutts LA, Leary MR, Zeveney AS, Hufnagle AS. A longitudinal analysis of the relationship between self-compassion and the psychological effects of perceived stress. Self and Identity. 2018; 17(6):609-26. [DOI:10.1080/15298868.2017.1422537]

- Lee JK. Emotional expressions and brand status. Journal of Marketing Research. 2021; 58(6):1178-96. [DOI:10.1177/00222437211037340]

- Yela JR, Crego A, Buz J, Sánchez-Zaballos E, Gómez-Martínez MÁ. Reductions in experiential avoidance explain changes in anxiety, depression and well-being after a mindfulness and self-compassion (MSC) training. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 2022; 95(2):402-22. [DOI:10.1111/papt.12375] [PMID]

- Miyagawa Y, Niiya Y, Taniguchi J. When life gives you lemons, make lemonade: Self-compassion increases adaptive beliefs about failure. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2020; 21(2):2051-68. [DOI:10.1007/s10902-019-00172-0]

- Inwood E, Ferrari M. Mechanisms of change in the relationship between self-compassion, emotion regulation, and mental health: A systematic review. Applied Psychology. Health and well-being. 2018; 10(2):215-35. [DOI:10.1111/aphw.12127] [PMID]

- Shapira LB, Mongrain M. The benefits of self-compassion and optimism exercises for individuals vulnerable to depression. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2010; 5(5):377-89. [DOI:10.1080/17439760.2010.516763]

- Briere J. CDS Cognitive Distortion Scales: Professional Manual. Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2000. [Link]

- Diener E. Assessing well-being: The collected works of Ed Diener. Dordrecht: Springer Science & Business Media; 2009. [Link]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Publications; 2017. [Link]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2004; 36(4):717-31. [DOI:10.3758/BF03206553] [PMID]

- Keyes KM, Gary D, O'Malley PM, Hamilton A, Schulenberg J. Recent increases in depressive symptoms among US adolescents: Trends from 1991 to 2018. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2019; 54(8):987-96. [DOI:10.1007/s00127-019-01697-8] [PMID]

- Akin, A. Self-Compassion and Interpersonal Cognitive Distortions. Hacettepe University Journal of Education. 2010; 39:1-9. [Link]

- Gao J, Feng Y, Xu S, Wilson A, Li H, Wang X, et al. Appearance anxiety and social anxiety: A mediated model of self-compassion. Frontiers in Public Health. 2023; 11:1105428. [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1105428] [PMID]

- Akin A, Iskender M. Self-compassion and internet addiction. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology.2011; 10(3):215-21. [Link]

- Neff KD, Germer CK. A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2013; 69(1):28-44. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.21923] [PMID]

- Gilbert P, Procter S. Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism: Overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy: An International Journal of Theory & Practice. 2006; 13(6):353-79. [Link]

Article type: Original Research Articles |

Subject:

Psychology

Received: 2023/11/30 | Accepted: 2024/03/12 | Published: 2025/06/1

Received: 2023/11/30 | Accepted: 2024/03/12 | Published: 2025/06/1

Send email to the article author