Volume 15, Issue 4 (December 2017)

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2017, 15(4): 341-350 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ebadi S, Naderifarjad Z. Dynamic Assessment of a Schizophrenic Foreign Language Learner . Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2017; 15 (4) :341-350

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-559-en.html

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-559-en.html

1- Department of Foreign Languages, Faculty of Literature and Humanities, Razi University, Kermanshah, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 517 kb]

(1617 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4981 Views)

Full-Text: (1087 Views)

1. Introduction

Dynamic Assessment (DA) is a subset of interactive assessment that involves purposeful and intended meditational teaching and the assessment of the ramification of that teaching on succeeding performance [1]. Its historical roots go back to Vygotsky and Feuerstein. DA rests on four assumptions: a. Accumulated knowledge is not indicative of the ability to acquire new knowledge. b. Everyone performs at less than 100% of capacity. c. The best test of any performance is a sample of that performance. d. There are many impediments that can mask one’s ability; when the obstacles are eliminated, greater ability than was suspected is often unveiled [1].

Vygotsky [2] defined the difference between individuals’ unassisted and assisted performance as their Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) stating that the level of performance they are able to reach with intervention is the indication of their future unassisted performance. Mediation is the fundamental notion of Vygotsky’s theory of mind. Two general kinds of mediation are available in DA research: first, interactionist DA that follows Vygotsky’s preference for collaborative dialogue, in which assistance comes out of the interaction between the mediator and the learner, and is therefore highly sensitive to the learner’s ZPD; and second, interventionist DA that remains closer to certain forms of static assessment and psychometric properties [3]. DA implements microgenesis as the general analytical framework to look into the level of self-regulation in learners’ progress. The microgenetic method [4] “primarily concerns the reorganization and development of mediation over a relatively short span of time”.

According to most experts, one of the critical applications of DA is when learning appears to be prevented by evident mental retardation, learning disability, emotional disturbance, personality disorder, or motivational deficit [5]. The function of DA is, therefore, to realize impediments to more efficacious learning and performance, to discover ways to overcome those obstacles, and to assess the effects of removal of obstacles on subsequent learning and performance effectiveness [6].

Schizophrenia is a chronic and debilitating illness. Its symptoms include deficits in cognition and changes in effect and behavior which may be perceived as bizarre. It is typical for a person to experience delusions, paranoia, and hallucinations [7]. The domains of 7 cognitive deficits suffered by patients include speed of processing, attention/vigilance, working memory, verbal learning and memory, visual learning and memory, reasoning and problem solving, verbal comprehension, and social cognition [8]. Two primary cognitive deficits associated with schizophrenia are verbal memory impairment and executive dysfunction. Verbal memory is how the person hears a piece of information and retains it for future purpose. This includes a person’s ability to think, concentrate, formulate ideas and remember [7]. Executive dysfunction includes the inability to think in an abstract manner or use information that will be needed in the future [9]. Cognitive deterioration in schizophrenia has been described to encompass executive functions and working memory [10].

Based on the assumptions for the applicability of DA and obstacles which masks one’s ability in psychiatric disorder, in general, and schizophrenia, in particular, this study is going to analyze a schizophrenic ZPD and to determine whether a patient is responsive to mediation in learning a foreign language. Accordingly, the present study was guided by the following question: What does microgenesis reveal about the schizophrenic L2 learner’s ZPD in grammatical ability?

Application of DA in Foreign Language Teaching with Disabled Students DA is used to yield information that is difficult or unattainable by other known methods, especially in certain clinical populations. DA has also been applied with second-language learners without issues of determining the need for special education services [11-13].

Schneider and Ganschow [13] describe the association of the concept of DA with assessment and instruction of at-risk foreign and second-language learners. They describe its applicability for teaching a foreign language to students with identified dyslexia and other at-risk students. They explain how questions and guided discovery are used to assess learners’ knowledge of the native, foreign/second-language. Schneider and Ganschow propose applying DA procedures to help at-risk language learners develop metalinguistic awareness, which they believe will facilitate learning.

Barrera [11] applied his approach with Spanish-speaking Mexican-American high school students with a diagnosis of learning disability who were trying to learn English. This author focused on handwritten notes, evaluated on criteria of legibility, structure, and information units. In a pilot study seeking to differentiate typically developing second-language learners from those with a learning disability, 21 students were given curriculum-based pretest measures in reading, writing, and spelling. The intervention involved a “reflection and analysis” journal for vocabulary building before, during, and after classroom lectures. The teachers taught the students principles of note taking over a period of 2weeksusing the first and last entries as pretests and posttests. The students with learning disabilities showed significant growth following the intervention with greater gains in reading and writing than in spelling.

Dynamic assessment and schizophrenia

By their very nature, psychiatric disorders raise barriers to intellectual functioning, leading the classical psychoanalysts such as Sigmund Freud and Otto Fenichel (e.g., 1946) to write of neurotic stupidity. The more serious the disorder, the greater is the masking of intelligence [6].

Blaufarb [14] investigated the notion of masked intelligence in developmental disabilities and in the process introduced a form of DA in the field of psychopathology. Blaufarb observed that schizophrenic patients were usually identified by a deficiency in verbal abstracting ability, which is defined as the ability to assemble concrete verbal information and construct abstract meaning from it. Interpretation of proverbs had long been used as an informal test in the psychiatric examination of mental patients. He gave proverb tests to those patients and to “normal” adults under two stimulus conditions. The results led Blaufarb to conclude that his patients did indeed experience a deficit in information input channels that was at least partially overcome by changing the stimulus situation by enriching the input.

Blaufarb suggested that schizophrenic patients have an information input deficit that makes it difficult for them to derive meaning from minimal information. Although “normal” adults abstracted the singly administered proverbs better than schizophrenics, their superiority to schizophrenics disappeared with the administration of the enriched proverb set.

This study was replicated and extended by Hamlin, Haywood, and Folsom [15], who studied three levels of psychopathology (closed ward, open ward, and former patients with schizophrenia) and non-patients. Patients with severe schizophrenia (closed ward) and non-patients were not helped by the enriched procedure (mediation), but patients with a mild form of the disorder (open ward) and former patients showed significant improvement. Improvement with enriched input for the open ward patients and the former patients was interpreted to suggest that those persons did indeed have a deficit in input channels that was easily overcome by stimulus enrichment. Instrumental Enrichment (IE) programs [3]were developed so that it could provide the learner with an intensive interventional learning experience to remediate cognitive deficits stemming from psychological tool deprivation (International Center for the Enhancement of Learning Potential, 2011).

DA has also been applied to predict functional outcome of schizophrenia patients. Sergi, Kern, Mintz, and Green [16] compared DA and conventional assessment in predicting work skill acquisition in schizophrenia patients. The team dynamically administered Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), a popular test to assess executive functions and mental flexibility [17], to 57 schizophrenia patients such that information about the sorting rules and feedback about trial-to-trial performance was given to the patients during the intervention. Subsequently, the patients were assigned to undergo two work skill training sessions (index card filing and toilet tank assembly). Work skill acquisition was assessed immediately after the training session and at a three-month post-training follow-up. Patients with high learning potential (which was calculated from the gain scores obtained from the dynamically administered WCST) were found to acquire the work skills more readily compared with those patients with poorer learning potential. Multiple regression analysis showed that while participants’ pre-test WCST performance (conventional assessment) explained 13% of the variance in work skill acquisition as assessed immediately after training, gain scores from the dynamically administered WCST were able to explain an additional 15% of the variance.

For work skills assessed three months after training, pretest WCST performance (conventional assessment) explained 6% of the variance while gain scores from the dynamically administered WCST explained an additional 13% of the variance. Thus, the dynamically administered WCST had better predictive utility for work skill acquisition compared to conventional assessment. Reviewing relevant research articles shows the applicability of DA in various psychoeducational contexts. However, to date, there has been no study to report on the application of DA on schizophrenic foreign language learner. This study was designed to investigate the effects of mediation, or more appropriately within sociocultural theory, other-regulation, on the microgenetic development of a schizophrenic learner.

2. Methods

The participant of this case study was a schizophrenic university English major student named Saba. The onset of her illness was at the age of 18. Before her illness she has been a successful student; however, the strike of the illness led to the deterioration of her academic performance. She was given DIALANG test of grammar before tutorial sessions, and the result indicated B1 level in structure on the Council of Europe scale. DIALANG is an on-line diagnostic language testing system, which includes diagnostic tests in 14 European languages and is based on the six levels of Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR). It is the first major testing system that is oriented towards diagnosing the level of language skills and giving feedback to users rather than certifying their competence. It offers separate assessments in reading, writing, listening, grammatical structures, and vocabulary [18]. The DIALANG test of grammar is mainly focused on traditional morphology and syntax [19].

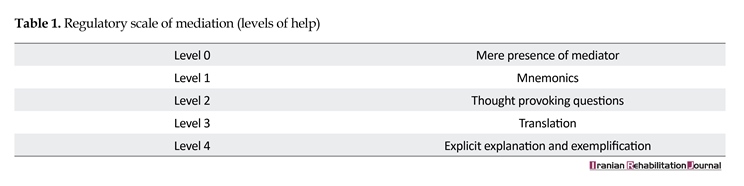

She had paragraph writing course which required writing different kinds of paragraphs. After analyzing her writing, correlative conjunctions and other grammatical points along with paragraph writing were determined to be the focus of DA sessions for a period of 5 months. Since reporting the whole study is beyond the scope of this article, DA sessions related to correlative conjunctions were opted for this study. The student and the mediator worked together through the enrichment program through which emerged the mediation regulatory scale (Table 1). The enrichment program provides students with mediated learning. The dialogic mediation in this study was based on the principles of interactionist DA, i.e., the mediation emerged out of the cooperative dialoguing between the mediator and the learners.

Dynamic Assessment (DA) is a subset of interactive assessment that involves purposeful and intended meditational teaching and the assessment of the ramification of that teaching on succeeding performance [1]. Its historical roots go back to Vygotsky and Feuerstein. DA rests on four assumptions: a. Accumulated knowledge is not indicative of the ability to acquire new knowledge. b. Everyone performs at less than 100% of capacity. c. The best test of any performance is a sample of that performance. d. There are many impediments that can mask one’s ability; when the obstacles are eliminated, greater ability than was suspected is often unveiled [1].

Vygotsky [2] defined the difference between individuals’ unassisted and assisted performance as their Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) stating that the level of performance they are able to reach with intervention is the indication of their future unassisted performance. Mediation is the fundamental notion of Vygotsky’s theory of mind. Two general kinds of mediation are available in DA research: first, interactionist DA that follows Vygotsky’s preference for collaborative dialogue, in which assistance comes out of the interaction between the mediator and the learner, and is therefore highly sensitive to the learner’s ZPD; and second, interventionist DA that remains closer to certain forms of static assessment and psychometric properties [3]. DA implements microgenesis as the general analytical framework to look into the level of self-regulation in learners’ progress. The microgenetic method [4] “primarily concerns the reorganization and development of mediation over a relatively short span of time”.

According to most experts, one of the critical applications of DA is when learning appears to be prevented by evident mental retardation, learning disability, emotional disturbance, personality disorder, or motivational deficit [5]. The function of DA is, therefore, to realize impediments to more efficacious learning and performance, to discover ways to overcome those obstacles, and to assess the effects of removal of obstacles on subsequent learning and performance effectiveness [6].

Schizophrenia is a chronic and debilitating illness. Its symptoms include deficits in cognition and changes in effect and behavior which may be perceived as bizarre. It is typical for a person to experience delusions, paranoia, and hallucinations [7]. The domains of 7 cognitive deficits suffered by patients include speed of processing, attention/vigilance, working memory, verbal learning and memory, visual learning and memory, reasoning and problem solving, verbal comprehension, and social cognition [8]. Two primary cognitive deficits associated with schizophrenia are verbal memory impairment and executive dysfunction. Verbal memory is how the person hears a piece of information and retains it for future purpose. This includes a person’s ability to think, concentrate, formulate ideas and remember [7]. Executive dysfunction includes the inability to think in an abstract manner or use information that will be needed in the future [9]. Cognitive deterioration in schizophrenia has been described to encompass executive functions and working memory [10].

Based on the assumptions for the applicability of DA and obstacles which masks one’s ability in psychiatric disorder, in general, and schizophrenia, in particular, this study is going to analyze a schizophrenic ZPD and to determine whether a patient is responsive to mediation in learning a foreign language. Accordingly, the present study was guided by the following question: What does microgenesis reveal about the schizophrenic L2 learner’s ZPD in grammatical ability?

Application of DA in Foreign Language Teaching with Disabled Students DA is used to yield information that is difficult or unattainable by other known methods, especially in certain clinical populations. DA has also been applied with second-language learners without issues of determining the need for special education services [11-13].

Schneider and Ganschow [13] describe the association of the concept of DA with assessment and instruction of at-risk foreign and second-language learners. They describe its applicability for teaching a foreign language to students with identified dyslexia and other at-risk students. They explain how questions and guided discovery are used to assess learners’ knowledge of the native, foreign/second-language. Schneider and Ganschow propose applying DA procedures to help at-risk language learners develop metalinguistic awareness, which they believe will facilitate learning.

Barrera [11] applied his approach with Spanish-speaking Mexican-American high school students with a diagnosis of learning disability who were trying to learn English. This author focused on handwritten notes, evaluated on criteria of legibility, structure, and information units. In a pilot study seeking to differentiate typically developing second-language learners from those with a learning disability, 21 students were given curriculum-based pretest measures in reading, writing, and spelling. The intervention involved a “reflection and analysis” journal for vocabulary building before, during, and after classroom lectures. The teachers taught the students principles of note taking over a period of 2weeksusing the first and last entries as pretests and posttests. The students with learning disabilities showed significant growth following the intervention with greater gains in reading and writing than in spelling.

Dynamic assessment and schizophrenia

By their very nature, psychiatric disorders raise barriers to intellectual functioning, leading the classical psychoanalysts such as Sigmund Freud and Otto Fenichel (e.g., 1946) to write of neurotic stupidity. The more serious the disorder, the greater is the masking of intelligence [6].

Blaufarb [14] investigated the notion of masked intelligence in developmental disabilities and in the process introduced a form of DA in the field of psychopathology. Blaufarb observed that schizophrenic patients were usually identified by a deficiency in verbal abstracting ability, which is defined as the ability to assemble concrete verbal information and construct abstract meaning from it. Interpretation of proverbs had long been used as an informal test in the psychiatric examination of mental patients. He gave proverb tests to those patients and to “normal” adults under two stimulus conditions. The results led Blaufarb to conclude that his patients did indeed experience a deficit in information input channels that was at least partially overcome by changing the stimulus situation by enriching the input.

Blaufarb suggested that schizophrenic patients have an information input deficit that makes it difficult for them to derive meaning from minimal information. Although “normal” adults abstracted the singly administered proverbs better than schizophrenics, their superiority to schizophrenics disappeared with the administration of the enriched proverb set.

This study was replicated and extended by Hamlin, Haywood, and Folsom [15], who studied three levels of psychopathology (closed ward, open ward, and former patients with schizophrenia) and non-patients. Patients with severe schizophrenia (closed ward) and non-patients were not helped by the enriched procedure (mediation), but patients with a mild form of the disorder (open ward) and former patients showed significant improvement. Improvement with enriched input for the open ward patients and the former patients was interpreted to suggest that those persons did indeed have a deficit in input channels that was easily overcome by stimulus enrichment. Instrumental Enrichment (IE) programs [3]were developed so that it could provide the learner with an intensive interventional learning experience to remediate cognitive deficits stemming from psychological tool deprivation (International Center for the Enhancement of Learning Potential, 2011).

DA has also been applied to predict functional outcome of schizophrenia patients. Sergi, Kern, Mintz, and Green [16] compared DA and conventional assessment in predicting work skill acquisition in schizophrenia patients. The team dynamically administered Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), a popular test to assess executive functions and mental flexibility [17], to 57 schizophrenia patients such that information about the sorting rules and feedback about trial-to-trial performance was given to the patients during the intervention. Subsequently, the patients were assigned to undergo two work skill training sessions (index card filing and toilet tank assembly). Work skill acquisition was assessed immediately after the training session and at a three-month post-training follow-up. Patients with high learning potential (which was calculated from the gain scores obtained from the dynamically administered WCST) were found to acquire the work skills more readily compared with those patients with poorer learning potential. Multiple regression analysis showed that while participants’ pre-test WCST performance (conventional assessment) explained 13% of the variance in work skill acquisition as assessed immediately after training, gain scores from the dynamically administered WCST were able to explain an additional 15% of the variance.

For work skills assessed three months after training, pretest WCST performance (conventional assessment) explained 6% of the variance while gain scores from the dynamically administered WCST explained an additional 13% of the variance. Thus, the dynamically administered WCST had better predictive utility for work skill acquisition compared to conventional assessment. Reviewing relevant research articles shows the applicability of DA in various psychoeducational contexts. However, to date, there has been no study to report on the application of DA on schizophrenic foreign language learner. This study was designed to investigate the effects of mediation, or more appropriately within sociocultural theory, other-regulation, on the microgenetic development of a schizophrenic learner.

2. Methods

The participant of this case study was a schizophrenic university English major student named Saba. The onset of her illness was at the age of 18. Before her illness she has been a successful student; however, the strike of the illness led to the deterioration of her academic performance. She was given DIALANG test of grammar before tutorial sessions, and the result indicated B1 level in structure on the Council of Europe scale. DIALANG is an on-line diagnostic language testing system, which includes diagnostic tests in 14 European languages and is based on the six levels of Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR). It is the first major testing system that is oriented towards diagnosing the level of language skills and giving feedback to users rather than certifying their competence. It offers separate assessments in reading, writing, listening, grammatical structures, and vocabulary [18]. The DIALANG test of grammar is mainly focused on traditional morphology and syntax [19].

She had paragraph writing course which required writing different kinds of paragraphs. After analyzing her writing, correlative conjunctions and other grammatical points along with paragraph writing were determined to be the focus of DA sessions for a period of 5 months. Since reporting the whole study is beyond the scope of this article, DA sessions related to correlative conjunctions were opted for this study. The student and the mediator worked together through the enrichment program through which emerged the mediation regulatory scale (Table 1). The enrichment program provides students with mediated learning. The dialogic mediation in this study was based on the principles of interactionist DA, i.e., the mediation emerged out of the cooperative dialoguing between the mediator and the learners.

The students who struggle with language were at a disadvantage. They depended on more explicit instruction of the language systems underlying the need to learn new language [13]. Accordingly, the levels of help started with mere presence of mediator. It continued with using mnemonics (memory aids), thought-provoking questions, translation, and eventually direct explanation and exemplification. It must be noted that thought-provoking questions and translation were used flexibly in order, which means the interactions determined the one that should be used first; accordingly, the type of meditational move, and the number and frequency of assistance were more important than their succession in this study. This scale was employed flexibly by the mediator through mediation in the enrichment program (Table 1).

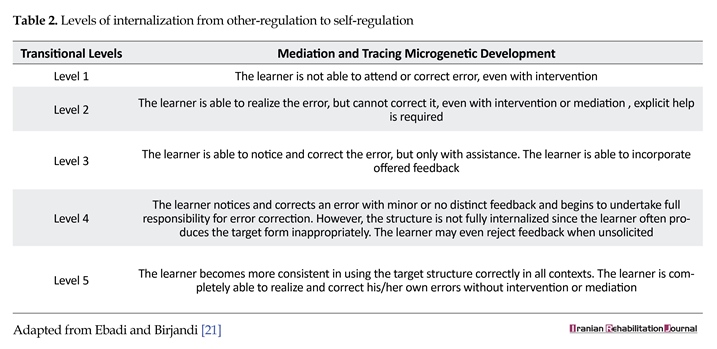

The touchstone for evaluating mediation and tracing microgenetic development from other regulation to self-regulation within the ZPD was five transitional levels developed by Aljaafreh and Lantolf [20] (Table 2). To evaluate mediation within the ZPD, Aljaafreh and Lantolf [20] developed five transitional levels of mediation strategies and techniques to trace learners’ microgenetic development from other-regulated (mediator regulates learning) to self-regulated performance (the learner regulates his/her learning without intervention) within DA sessions and transfer tasks. The main points of each level are pinpointed in Table 2.

3. Results

Following a SCT-based DA framework, this study prioritized qualitative approach for data collection and analysis which was best suited to the ZPD concept. Language-Related Episodes (LREs) have been used as a unit of analysis. A language-related episode is actually any part of a dialogue where students talk about the language they are producing, question their language use, or correct themselves or others [21, 22]. LREs are used in classroom research to identify the degree to which language learners address

The touchstone for evaluating mediation and tracing microgenetic development from other regulation to self-regulation within the ZPD was five transitional levels developed by Aljaafreh and Lantolf [20] (Table 2). To evaluate mediation within the ZPD, Aljaafreh and Lantolf [20] developed five transitional levels of mediation strategies and techniques to trace learners’ microgenetic development from other-regulated (mediator regulates learning) to self-regulated performance (the learner regulates his/her learning without intervention) within DA sessions and transfer tasks. The main points of each level are pinpointed in Table 2.

3. Results

Following a SCT-based DA framework, this study prioritized qualitative approach for data collection and analysis which was best suited to the ZPD concept. Language-Related Episodes (LREs) have been used as a unit of analysis. A language-related episode is actually any part of a dialogue where students talk about the language they are producing, question their language use, or correct themselves or others [21, 22]. LREs are used in classroom research to identify the degree to which language learners address

recently learned or problematic features of the target language.

Research has shown that LREs represent language learning in progress and therefore are the site of language learning [23, 24]. This study used LREs as a part of its methodology to investigate collaborative learning and to keep record of moment by moment mediation within ZPD. The researchers looked for some evidence of progress in using a correlative conjunction in DA session which continued for nearly 60 minutes. The following LREs were taken from interactions between the mediator and Saba during their work together.

Episode 1, session 1

The first episode was taken from an interaction between tutor and Saba at first session. This initial interaction between mediator and Saba represents her actual competence in this area. In the following excerpt, when she was asked if she knew about using correlative conjunctions, she replied “yes,” but her sentences indicated that she did not know anything. The tutor explained and exemplified the grammar. The focus of the study was correlative conjunctions; therefore, other faulty parts including subject-verb agreement were not dealt with:

T: Do you know about correlative conjunctions such as either…or, neither…nor, not only … but also

S: Ahh

S: Yes.

T: Give an example

S: My sister go to London either my brother.

S: Yahhh?

S: My sister go to London either my cousin.

S: Yahhh?

T: What does either…..or…..mean?

T: Can you translate your sentence.

S: Laughing

S: I don’t know.

S: Where is my mother?

T: She is out.

T: Direct explanation and exemplification by the mediator.

The interaction between the mediator and Saba reveals that she did not know anything about correlative conjunctions and she was in level 1 of internalization of assistance (Table 2). She did not have the sufficient basis from which to interpret the mediator’s help and had no awareness that there was even a problem. Thus, the mediator’s task was to bring the target form into focus.

Episode 2, mid sessions

Some interactions from different sessions are represented. The mere presence of the mediator and mnemonics are rigidly followed in all interactions since in the absence of mediator, Saba did not have the motivation to continue her work and made herself busy with other irrelevant jobs such as drawing lines or messing her writings, indicating the importance of mere presence of mediators as also suggested by Aljafreh and Lantolf [20].

Mnemonic (memory aids) was rigorously followed in all interactions as well. Mnemonics helped her to write equivalent elements and remember the inversion that happened with negative words. The pattern of those conjunctions was drawn to help Saba remember what she was doing. The parallel structures which are connected by correlative conjunctions are well represented by the lines and the words below them (verb, noun, and sentence)on both sides. In addition, inversion in independent clauses introduced by neither …nor and not only is shown by a question mark.

Because of the cognitive impairment, especially verbal and working memory impairment in these patients, mnemonics and other thought-provoking questions are essential to keep them in track of their work.

Interaction 1

T: Write a sentence please.

S: Ok!

S: Where is my mom?

S: She is out.

S: She draws mnemonics herself.

S: Either………………..or…………….. (Mnemonic)

Noun noun

Verb verb

Sentence sentence

S: (She explains for herself that similar structure must be used in blank parts).

S: Long silence

T: (The teacher refers her to the mnemonics.)

T: Why don’t you use a verb in blank part?

S: Either travel or travel.

T: Translate it.

S: Yahh, I must use another verb.

S: That’s right.

S: Either travel or go.

T: Translate it.

S: She translates the sentence in Farsi.

S: It’s better to say either travel or stay.

T: That’s right.W

Note: Her irrelevant questions are intentionally documented to show her mental disturbance.

Interaction 2

S: using mnemonics

S: Neither ………………..Nor……………………..

Noun noun

Verb verb

Sentence? sentence? (question marks indicate the inversion )

S: Neither old people nor old girl

S: Old girl?

S: No, Neither old people nor old object (antiques).

T: Can you translate the sentence?

S: Not elderly not antique

T: Ok, continue your sentence.

S: She looks at mnemonics.

S: I want to write sentence on both sides.

S: Neither does old people can play piano nor does objects can’t do anything.

S: I don’t know.

S: laughing

Note: Abnormalities of speech are observed

Interaction 3

Not only ……….but also…………….

Sentence? sentence

S: Not only ……silence

S: Not only I go to my house but also my cousin go to my house.

S: It should be in question form (self-explanation).

S: Not only do I go to my house but also do my cousin go to my house (self-correct).

T: There is a problem.

S: long silence…………(she is thinking)

S: What are you thinking about?

S: Nothing.

S: (She wanted to write another sentence).

T: (Mediator reminded her that they were correcting the sentence). She was not aware of the problem.

T: What’s the problem?

T: Is the inversion correct in the second clause?

S: Yes!

T: Look at the pattern (mnemonic).

S: No, It is not correct.

S: Not only do I go to my house but also my cousin goes to my house.

Note: She even forgets that she is correcting a sentence and wants to write a new one.

Interaction 4

Not only ……….but also…………….

Sentence? sentence

S: Either I go to restaurant or my sister goes to bar.

T: Translate it.

S: She translates the sentence in Farsi.

T: Does it make sense?

S: Let me change my sentence.

T: No, correct it.

S: Either I go to a restaurant or (silence)..

S: Either I go to a restaurant or I go to the bar.

T: Excellent!

In these sets of interaction, she first drew mnemonics and started writing sentences. These interactions revealed that she reacted positively to direct assistance. Her understanding had changed. She showed sign of development in her ZPD by responding to explicit help and moved up to level 3 of internalization. The learner was able to notice and correct an error, but only under other-regulation. She understood the tutor’s intervention and was able to react to the feedback offered. Regarding abnormalities in her speech, Chika [25] outlined the linguistic characteristics of schizophrenics as follows: 1. Failure to utter the intended lexical item; 2. Distraction by the sounds or senses of words, so that a discourse becomes a string of word associations rather than a presentation of previously intended information; 3. Breakdown of syntax and/or discourse; 4. Lack of awareness that the utterances are abnormal. These abnormalities are observed in Saba’s sentences. Her sentences were sometimes either obliquely related or completely unrelated, e.g., “Either I go to restaurant or my sister goes to bar,” “Neither does old people can play piano nor does objects can’t do anything”.

Thanks to the mediation and assistance as she could write syntactically correct sentences. However, her sentences did not make sense semantically. Although, these semantically odd sentences were not the focus of this study, “translation” of these kinds of sentences could help her to recognize the problem and modify them (interaction 4). Translating gave her an opportunity to think, recognize, and correct her own mistakes.

Episode 3, last sessions

Interaction 1

Not only ………………..but also ……………………..

Noun noun

Verb verb

Sentence? sentence

S: Not only flower but also basket.

T: Complete you sentence.

S: Silence

S: Not only flower but also basket.

S: Reading aloud and thinking.

S: Reading aloud and thinking.

S: Not only flower but also basket absorbed me.

T: Excellent!

Interaction 2

Neither ………………..Nor……………………..

Noun noun

Verb verb

Sentence? sentence?

S: Neither I speak loudly nor I speak……..

S: Silence.

S: Reading aloud.

S: Reading aloud.

S: Neither I speak loudly nor I speak quietly.

T: How should the sentence be?

S: Question form.

S: Neither do I speak loudly nor do I speak quietly.

T: Great!

These interactions highlighted the fact that the learner moved up to level 4 and just with minimal mediation she could concentrate. As a matter of fact what she needed for self-regulation was just a second chance with less explicit assistance. The learner noticed and corrected an error with minimal or no obvious feedback from the tutor and began to accept full responsibility for error correction. However, development had not become fully intramental or internalized, since the learner often produced the target form inaccurately and may still needed the tutor to confirm the adequacy of the correction.

4. Discussion

DA originated from the work of Reuven Feurestein [26] as a method for assessing intellectual potential and remediating cognitive deficits in individuals with mental retardation [13]. Unique to this approach is the role of the instructor as a facilitator of student learning. The underlying assumption of DA and instruction is that individuals can modify and improve their learning by working with trained teacher who provides mediations.

The assessment of schizophrenic students presents many challenges by the fact that their performance is affected by their cognitive deficits and antipsychotic drugs. This case study demonstrated how DA by meditational moves including presence of mediator, mnemonics, thought-provoking questions, and translation can overcome cognitive and behavioral impairment. This study reports the potentials of DA to uncover competence and knowledge which is depressed because of a psychiatric disorder. The microgenetic analysis revealed the learner could move up till level 4 of her ZPD and showed significant improvement. The study showed that DA can be a fair and viable choice for these kinds of patients for the following reasons:

First, schizophrenic students suffer from severe anxiety, extreme moodiness, disorganized speech, lack of motivation; however, the presence of a supportive mediator who provides a pleasant ‘error-making’ atmosphere by allowing rethinking time encourages them to find the solution, and to discover and correct initial mistakes.

Second, schizophrenics learn better through experience and hands-on interaction versus being expected to learn by formal instruction with the teacher posturing as knowing more than the learner [27]. DA in foreign and second-language instruction is an ongoing assessment cycle which involves both teacher and student. Teacher and student continuously learn from each other as they participate in a dialogue [13].

Third, many schizophrenic patients have memory loss or an inability to recall events or information [27]. This is well illustrated in Episode 2, Interaction 3. When Saba was in the course of correcting her sentence, she became silent for 2 minutes. Mediator asked her what she was thinking about, she answered nothing and wanted to write a new sentence instead of correcting her sentence. Mediator tried to remind her they were correcting sentence and by asking her to look at the drawn pattern (mnemonic), she could correct the sentence which had inversion problem. Mnemonic devices can be used as mediation to compensate such weaknesses. They are strategies that activate the right hemisphere of the brain to help learners remember details in language formation that need to be stored in the left hemisphere of the brain. They can be verbal or non-verbal [28].

Fourth, language is clearly affected in schizophrenia. Disorganized speech including derailment, topic shifting, and incoherence are major symptoms in the patients. They produce semantically odd sentences, e.g., “neither tiger nor butterfly eat rabbit”. Translation and thought-provoking questions as mediations can help them recognize these kinds of problems. In this study, when Saba was asked “can butterfly eat rabbit?” or when she was asked to translate such sentences, she became aware of her problems.

5. Conclusion

This study revealed that DA represents a viable adjunct, or alternative, when there are questions that a static approach cannot answer [29]. It is hoped that the result of this study contributes to the body of research into the roles and values of mediation in psychiatric disorders.

Acknowledgments

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors hereby gratefully acknowledge Dr. Seyed Hamid Mostafavi Abdolmaleki, faculty member of Iran University of Medical Sciences and also Boston University for his sincere reading of the article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

[1]Haywood HC, Tzuriel D. Applications and challenges in dynamic assessment. Peabody Journal of Education. 2002; 77(2):40–63. doi: 10.1207/s15327930pje7702_5

[2]Vygotsky LS. Mind in Society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1978.

[3]Poehner ME. Dynamic assessment: A Vygotskian approach to understanding and promoting L2 development (Vol. 9). Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media; 2008.

[4]Lantolf JP. Second language learning as a mediated process. Language Teaching. 2000; 33(02):79-96. doi: 10.1017/s0261444800015329

[5]Feuerstein RY. The dynamic assessment of retarded performers: The learning potential assessment device, theory, instruments, and techniques. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1979.

[6]Haywood HC, Lidz CS. Dynamic assessment in practice: Clinical and educational applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

[7]Nuechterlein, KH, Barch, DM, Gold JM, Goldberg TE, Green MF, Heaton RK. Identification of separable cognitive factors in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2004; 72:29-39. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.007

[8]Nuechterlein KH, Barch DM, Gold JM, Goldberg TE, Green MF, Heaton RK. Identification of separable cognitive factors in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2004; 72(1):29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.007

[9]Diamond RJ. What primary care physicians need to know about people with schizophrenia. Wisconsin Medical Journal. 2004; 103(6):29-33.

[10]Bersudsky Y, Fine J, Gorjaltsan I, Chen O, Walters J. Schizophrenia and second language acquisition. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2005; 29(4):535–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.01.004

[11]Barrera M. Curriculum-based dynamic assessment for new-or second-language learners with learning disabilities in secondary education settings. Assessment for Effective Intervention. 2003; 29(1):69-84. doi: 10.1177/073724770302900107

[12]Kozulin A, Garb E. Dynamic assessment of EFL text comprehension. School Psychology International. 2002; 23(1):112–27. doi: 10.1177/0143034302023001733

[13]Schneider E, Ganschow L. Dynamic assessment and instructional strategies for learners who struggle to learn a foreign language. Dyslexia. 2000; 6(1):72-82. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0909(200001/03)6:1<72::aid-dys162>3.0.co;2-b

[14]Blaufarb H. A demonstration of verbal abstracting ability in chronic schizophrenics under enriched stimulus and instructional conditions. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1962; 26(5):471–5. doi: 10.1037/h0045408

[15]Hamlin RM, Haywood HC, Folsom AT. Effect of enriched input on schizophrenic abstraction. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1965; 70(5):390–4. doi: 10.1037/h0022507

[16]Sergi MJ, Kern RS, Mintz J, Green MF. Learning potential and the prediction of work skill acquisition in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2005; 31(1):67-72. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi007

[17]Kongs SK, Thompson LL, Iverson GL, HeatonRK. Wisconsin card sorting test-64 card version (WCST-64). Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2000.

[18]Zhang S, Thompson N. DIALANG: A diagnostic language assessment system (review). The Canadian Modern Language Review/La revue canadienne des langues vivantes. 2004; 61(2):290–3. doi: 10.1353/cml.2005.0011

[19]Alderson JC. Diagnosing foreign language proficiency: The interface between learning and assessment. New York: Continuum; 2005

[20]Aljaafreh A, Lantolf P. Negative feedback as regulation and second language learning in the zone of proximal development. The Modern Language Journal. 1994; 78(4):465-83. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1994.tb02064.x

[21]Birjandi P, Ebadi S. Microgenesis in dynamic assessment of L2 learners’ socio-cognitive development via web 2.0. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2012; 32:34–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.01.006

[22]Swain M. Examining dialogue: another approach to content specification and to validating inferences drawn from test scores. Language Testing. 2001; 18(3):275–302. doi: 10.1177/026553220101800302

[23]Swain M, Lapkin S. Interaction and second language learning: two adolescent french immersion students working together. The Modern language Journal. 1998; 82(3):320–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1998.tb01209.x

[24]Ewald, J. Language-related episodes in an assessment context: A'small-group quiz'. Canadian Modern Language Review. 2005; 61(4):565-86. doi: 10.3138/cmlr.61.4.565

[25]Chaika E. A linguist looks at “schizophrenic” language. Brain and Language. 1974; 1(3):257–76. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(74)90040-6

[26]Feuerstein R. Instrumental enrichment. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1980.

[27]Hogarty GE, Flesher S. Practice principles of cognitive enhancement therapy for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1999; 25(4):693–708. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033411

[28]Mastropieri MA, Scruggs TE, Mushinski Fulk BJ. Teaching abstract vocabulary with the keyword method. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 1990; 23(2):92–6. doi: 10.1177/002221949002300203

[29]Humphries T, Krogh K, McKay R. Theoretical and practical considerations in the psychological and educational assessment of the student with intractable epilepsy: Dynamic assessment as an adjunct to static assessment. Seizure. 2001; 10(3):173–80. doi: 10.1053/seiz.2000.0490

Research has shown that LREs represent language learning in progress and therefore are the site of language learning [23, 24]. This study used LREs as a part of its methodology to investigate collaborative learning and to keep record of moment by moment mediation within ZPD. The researchers looked for some evidence of progress in using a correlative conjunction in DA session which continued for nearly 60 minutes. The following LREs were taken from interactions between the mediator and Saba during their work together.

Episode 1, session 1

The first episode was taken from an interaction between tutor and Saba at first session. This initial interaction between mediator and Saba represents her actual competence in this area. In the following excerpt, when she was asked if she knew about using correlative conjunctions, she replied “yes,” but her sentences indicated that she did not know anything. The tutor explained and exemplified the grammar. The focus of the study was correlative conjunctions; therefore, other faulty parts including subject-verb agreement were not dealt with:

T: Do you know about correlative conjunctions such as either…or, neither…nor, not only … but also

S: Ahh

S: Yes.

T: Give an example

S: My sister go to London either my brother.

S: Yahhh?

S: My sister go to London either my cousin.

S: Yahhh?

T: What does either…..or…..mean?

T: Can you translate your sentence.

S: Laughing

S: I don’t know.

S: Where is my mother?

T: She is out.

T: Direct explanation and exemplification by the mediator.

The interaction between the mediator and Saba reveals that she did not know anything about correlative conjunctions and she was in level 1 of internalization of assistance (Table 2). She did not have the sufficient basis from which to interpret the mediator’s help and had no awareness that there was even a problem. Thus, the mediator’s task was to bring the target form into focus.

Episode 2, mid sessions

Some interactions from different sessions are represented. The mere presence of the mediator and mnemonics are rigidly followed in all interactions since in the absence of mediator, Saba did not have the motivation to continue her work and made herself busy with other irrelevant jobs such as drawing lines or messing her writings, indicating the importance of mere presence of mediators as also suggested by Aljafreh and Lantolf [20].

Mnemonic (memory aids) was rigorously followed in all interactions as well. Mnemonics helped her to write equivalent elements and remember the inversion that happened with negative words. The pattern of those conjunctions was drawn to help Saba remember what she was doing. The parallel structures which are connected by correlative conjunctions are well represented by the lines and the words below them (verb, noun, and sentence)on both sides. In addition, inversion in independent clauses introduced by neither …nor and not only is shown by a question mark.

Because of the cognitive impairment, especially verbal and working memory impairment in these patients, mnemonics and other thought-provoking questions are essential to keep them in track of their work.

Interaction 1

T: Write a sentence please.

S: Ok!

S: Where is my mom?

S: She is out.

S: She draws mnemonics herself.

S: Either………………..or…………….. (Mnemonic)

Noun noun

Verb verb

Sentence sentence

S: (She explains for herself that similar structure must be used in blank parts).

S: Long silence

T: (The teacher refers her to the mnemonics.)

T: Why don’t you use a verb in blank part?

S: Either travel or travel.

T: Translate it.

S: Yahh, I must use another verb.

S: That’s right.

S: Either travel or go.

T: Translate it.

S: She translates the sentence in Farsi.

S: It’s better to say either travel or stay.

T: That’s right.W

Note: Her irrelevant questions are intentionally documented to show her mental disturbance.

Interaction 2

S: using mnemonics

S: Neither ………………..Nor……………………..

Noun noun

Verb verb

Sentence? sentence? (question marks indicate the inversion )

S: Neither old people nor old girl

S: Old girl?

S: No, Neither old people nor old object (antiques).

T: Can you translate the sentence?

S: Not elderly not antique

T: Ok, continue your sentence.

S: She looks at mnemonics.

S: I want to write sentence on both sides.

S: Neither does old people can play piano nor does objects can’t do anything.

S: I don’t know.

S: laughing

Note: Abnormalities of speech are observed

Interaction 3

Not only ……….but also…………….

Sentence? sentence

S: Not only ……silence

S: Not only I go to my house but also my cousin go to my house.

S: It should be in question form (self-explanation).

S: Not only do I go to my house but also do my cousin go to my house (self-correct).

T: There is a problem.

S: long silence…………(she is thinking)

S: What are you thinking about?

S: Nothing.

S: (She wanted to write another sentence).

T: (Mediator reminded her that they were correcting the sentence). She was not aware of the problem.

T: What’s the problem?

T: Is the inversion correct in the second clause?

S: Yes!

T: Look at the pattern (mnemonic).

S: No, It is not correct.

S: Not only do I go to my house but also my cousin goes to my house.

Note: She even forgets that she is correcting a sentence and wants to write a new one.

Interaction 4

Not only ……….but also…………….

Sentence? sentence

S: Either I go to restaurant or my sister goes to bar.

T: Translate it.

S: She translates the sentence in Farsi.

T: Does it make sense?

S: Let me change my sentence.

T: No, correct it.

S: Either I go to a restaurant or (silence)..

S: Either I go to a restaurant or I go to the bar.

T: Excellent!

In these sets of interaction, she first drew mnemonics and started writing sentences. These interactions revealed that she reacted positively to direct assistance. Her understanding had changed. She showed sign of development in her ZPD by responding to explicit help and moved up to level 3 of internalization. The learner was able to notice and correct an error, but only under other-regulation. She understood the tutor’s intervention and was able to react to the feedback offered. Regarding abnormalities in her speech, Chika [25] outlined the linguistic characteristics of schizophrenics as follows: 1. Failure to utter the intended lexical item; 2. Distraction by the sounds or senses of words, so that a discourse becomes a string of word associations rather than a presentation of previously intended information; 3. Breakdown of syntax and/or discourse; 4. Lack of awareness that the utterances are abnormal. These abnormalities are observed in Saba’s sentences. Her sentences were sometimes either obliquely related or completely unrelated, e.g., “Either I go to restaurant or my sister goes to bar,” “Neither does old people can play piano nor does objects can’t do anything”.

Thanks to the mediation and assistance as she could write syntactically correct sentences. However, her sentences did not make sense semantically. Although, these semantically odd sentences were not the focus of this study, “translation” of these kinds of sentences could help her to recognize the problem and modify them (interaction 4). Translating gave her an opportunity to think, recognize, and correct her own mistakes.

Episode 3, last sessions

Interaction 1

Not only ………………..but also ……………………..

Noun noun

Verb verb

Sentence? sentence

S: Not only flower but also basket.

T: Complete you sentence.

S: Silence

S: Not only flower but also basket.

S: Reading aloud and thinking.

S: Reading aloud and thinking.

S: Not only flower but also basket absorbed me.

T: Excellent!

Interaction 2

Neither ………………..Nor……………………..

Noun noun

Verb verb

Sentence? sentence?

S: Neither I speak loudly nor I speak……..

S: Silence.

S: Reading aloud.

S: Reading aloud.

S: Neither I speak loudly nor I speak quietly.

T: How should the sentence be?

S: Question form.

S: Neither do I speak loudly nor do I speak quietly.

T: Great!

These interactions highlighted the fact that the learner moved up to level 4 and just with minimal mediation she could concentrate. As a matter of fact what she needed for self-regulation was just a second chance with less explicit assistance. The learner noticed and corrected an error with minimal or no obvious feedback from the tutor and began to accept full responsibility for error correction. However, development had not become fully intramental or internalized, since the learner often produced the target form inaccurately and may still needed the tutor to confirm the adequacy of the correction.

4. Discussion

DA originated from the work of Reuven Feurestein [26] as a method for assessing intellectual potential and remediating cognitive deficits in individuals with mental retardation [13]. Unique to this approach is the role of the instructor as a facilitator of student learning. The underlying assumption of DA and instruction is that individuals can modify and improve their learning by working with trained teacher who provides mediations.

The assessment of schizophrenic students presents many challenges by the fact that their performance is affected by their cognitive deficits and antipsychotic drugs. This case study demonstrated how DA by meditational moves including presence of mediator, mnemonics, thought-provoking questions, and translation can overcome cognitive and behavioral impairment. This study reports the potentials of DA to uncover competence and knowledge which is depressed because of a psychiatric disorder. The microgenetic analysis revealed the learner could move up till level 4 of her ZPD and showed significant improvement. The study showed that DA can be a fair and viable choice for these kinds of patients for the following reasons:

First, schizophrenic students suffer from severe anxiety, extreme moodiness, disorganized speech, lack of motivation; however, the presence of a supportive mediator who provides a pleasant ‘error-making’ atmosphere by allowing rethinking time encourages them to find the solution, and to discover and correct initial mistakes.

Second, schizophrenics learn better through experience and hands-on interaction versus being expected to learn by formal instruction with the teacher posturing as knowing more than the learner [27]. DA in foreign and second-language instruction is an ongoing assessment cycle which involves both teacher and student. Teacher and student continuously learn from each other as they participate in a dialogue [13].

Third, many schizophrenic patients have memory loss or an inability to recall events or information [27]. This is well illustrated in Episode 2, Interaction 3. When Saba was in the course of correcting her sentence, she became silent for 2 minutes. Mediator asked her what she was thinking about, she answered nothing and wanted to write a new sentence instead of correcting her sentence. Mediator tried to remind her they were correcting sentence and by asking her to look at the drawn pattern (mnemonic), she could correct the sentence which had inversion problem. Mnemonic devices can be used as mediation to compensate such weaknesses. They are strategies that activate the right hemisphere of the brain to help learners remember details in language formation that need to be stored in the left hemisphere of the brain. They can be verbal or non-verbal [28].

Fourth, language is clearly affected in schizophrenia. Disorganized speech including derailment, topic shifting, and incoherence are major symptoms in the patients. They produce semantically odd sentences, e.g., “neither tiger nor butterfly eat rabbit”. Translation and thought-provoking questions as mediations can help them recognize these kinds of problems. In this study, when Saba was asked “can butterfly eat rabbit?” or when she was asked to translate such sentences, she became aware of her problems.

5. Conclusion

This study revealed that DA represents a viable adjunct, or alternative, when there are questions that a static approach cannot answer [29]. It is hoped that the result of this study contributes to the body of research into the roles and values of mediation in psychiatric disorders.

Acknowledgments

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors hereby gratefully acknowledge Dr. Seyed Hamid Mostafavi Abdolmaleki, faculty member of Iran University of Medical Sciences and also Boston University for his sincere reading of the article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

[1]Haywood HC, Tzuriel D. Applications and challenges in dynamic assessment. Peabody Journal of Education. 2002; 77(2):40–63. doi: 10.1207/s15327930pje7702_5

[2]Vygotsky LS. Mind in Society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1978.

[3]Poehner ME. Dynamic assessment: A Vygotskian approach to understanding and promoting L2 development (Vol. 9). Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media; 2008.

[4]Lantolf JP. Second language learning as a mediated process. Language Teaching. 2000; 33(02):79-96. doi: 10.1017/s0261444800015329

[5]Feuerstein RY. The dynamic assessment of retarded performers: The learning potential assessment device, theory, instruments, and techniques. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1979.

[6]Haywood HC, Lidz CS. Dynamic assessment in practice: Clinical and educational applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

[7]Nuechterlein, KH, Barch, DM, Gold JM, Goldberg TE, Green MF, Heaton RK. Identification of separable cognitive factors in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2004; 72:29-39. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.007

[8]Nuechterlein KH, Barch DM, Gold JM, Goldberg TE, Green MF, Heaton RK. Identification of separable cognitive factors in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2004; 72(1):29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.007

[9]Diamond RJ. What primary care physicians need to know about people with schizophrenia. Wisconsin Medical Journal. 2004; 103(6):29-33.

[10]Bersudsky Y, Fine J, Gorjaltsan I, Chen O, Walters J. Schizophrenia and second language acquisition. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2005; 29(4):535–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.01.004

[11]Barrera M. Curriculum-based dynamic assessment for new-or second-language learners with learning disabilities in secondary education settings. Assessment for Effective Intervention. 2003; 29(1):69-84. doi: 10.1177/073724770302900107

[12]Kozulin A, Garb E. Dynamic assessment of EFL text comprehension. School Psychology International. 2002; 23(1):112–27. doi: 10.1177/0143034302023001733

[13]Schneider E, Ganschow L. Dynamic assessment and instructional strategies for learners who struggle to learn a foreign language. Dyslexia. 2000; 6(1):72-82. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0909(200001/03)6:1<72::aid-dys162>3.0.co;2-b

[14]Blaufarb H. A demonstration of verbal abstracting ability in chronic schizophrenics under enriched stimulus and instructional conditions. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1962; 26(5):471–5. doi: 10.1037/h0045408

[15]Hamlin RM, Haywood HC, Folsom AT. Effect of enriched input on schizophrenic abstraction. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1965; 70(5):390–4. doi: 10.1037/h0022507

[16]Sergi MJ, Kern RS, Mintz J, Green MF. Learning potential and the prediction of work skill acquisition in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2005; 31(1):67-72. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi007

[17]Kongs SK, Thompson LL, Iverson GL, HeatonRK. Wisconsin card sorting test-64 card version (WCST-64). Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2000.

[18]Zhang S, Thompson N. DIALANG: A diagnostic language assessment system (review). The Canadian Modern Language Review/La revue canadienne des langues vivantes. 2004; 61(2):290–3. doi: 10.1353/cml.2005.0011

[19]Alderson JC. Diagnosing foreign language proficiency: The interface between learning and assessment. New York: Continuum; 2005

[20]Aljaafreh A, Lantolf P. Negative feedback as regulation and second language learning in the zone of proximal development. The Modern Language Journal. 1994; 78(4):465-83. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1994.tb02064.x

[21]Birjandi P, Ebadi S. Microgenesis in dynamic assessment of L2 learners’ socio-cognitive development via web 2.0. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2012; 32:34–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.01.006

[22]Swain M. Examining dialogue: another approach to content specification and to validating inferences drawn from test scores. Language Testing. 2001; 18(3):275–302. doi: 10.1177/026553220101800302

[23]Swain M, Lapkin S. Interaction and second language learning: two adolescent french immersion students working together. The Modern language Journal. 1998; 82(3):320–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1998.tb01209.x

[24]Ewald, J. Language-related episodes in an assessment context: A'small-group quiz'. Canadian Modern Language Review. 2005; 61(4):565-86. doi: 10.3138/cmlr.61.4.565

[25]Chaika E. A linguist looks at “schizophrenic” language. Brain and Language. 1974; 1(3):257–76. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(74)90040-6

[26]Feuerstein R. Instrumental enrichment. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1980.

[27]Hogarty GE, Flesher S. Practice principles of cognitive enhancement therapy for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1999; 25(4):693–708. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033411

[28]Mastropieri MA, Scruggs TE, Mushinski Fulk BJ. Teaching abstract vocabulary with the keyword method. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 1990; 23(2):92–6. doi: 10.1177/002221949002300203

[29]Humphries T, Krogh K, McKay R. Theoretical and practical considerations in the psychological and educational assessment of the student with intractable epilepsy: Dynamic assessment as an adjunct to static assessment. Seizure. 2001; 10(3):173–80. doi: 10.1053/seiz.2000.0490

Article type: Original Research Articles |

Received: 2017/07/21 | Accepted: 2017/10/6 | Published: 2017/12/1

Received: 2017/07/21 | Accepted: 2017/10/6 | Published: 2017/12/1

References

1. Haywood HC, Tzuriel D. Applications and challenges in dynamic assessment. Peabody Journal of Education. 2002; 77(2):40–63. doi: 10.1207/s15327930pje7702_5 [DOI:10.1207/S15327930PJE7702_5]

2. Vygotsky LS. Mind in Society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1978.

3. Poehner ME. Dynamic assessment: A Vygotskian approach to understanding and promoting L2 development (Vol. 9). Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media; 2008.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-75775-9

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-75775-9_2

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-75775-9_9

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-75775-9_1

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-75775-9_5

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-75775-9_7

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-75775-9_4

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-75775-9_6

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-75775-9_8 [DOI:10.1007/978-0-387-75775-9_3]

4. Lantolf JP. Second language learning as a mediated process. Language Teaching. 2000; 33(02):79-96. doi: 10.1017/s0261444800015329 [DOI:10.1017/S0261444800015329]

5. Feuerstein RY. The dynamic assessment of retarded performers: The learning potential assessment device, theory, instruments, and techniques. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1979.

6. Haywood HC, Lidz CS. Dynamic assessment in practice: Clinical and educational applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [DOI:10.1017/CBO9780511607516]

7. Nuechterlein, KH, Barch, DM, Gold JM, Goldberg TE, Green MF, Heaton RK. Identification of separable cognitive factors in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2004; 72:29-39. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.007 [DOI:10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.007]

8. Nuechterlein KH, Barch DM, Gold JM, Goldberg TE, Green MF, Heaton RK. Identification of separable cognitive factors in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2004; 72(1):29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.007 [DOI:10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.007]

9. Diamond RJ. What primary care physicians need to know about people with schizophrenia. Wisconsin Medical Journal. 2004; 103(6):29-33.

10. Bersudsky Y, Fine J, Gorjaltsan I, Chen O, Walters J. Schizophrenia and second language acquisition. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2005; 29(4):535–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.01.004 [DOI:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.01.004]

11. Barrera M. Curriculum-based dynamic assessment for new-or second-language learners with learning disabilities in secondary education settings. Assessment for Effective Intervention. 2003; 29(1):69-84. doi: 10.1177/073724770302900107 [DOI:10.1177/073724770302900107]

12. Kozulin A, Garb E. Dynamic assessment of EFL text comprehension. School Psychology International. 2002; 23(1):112–27. doi: 10.1177/0143034302023001733 [DOI:10.1177/0143034302023001733]

13. Schneider E, Ganschow L. Dynamic assessment and instructional strategies for learners who struggle to learn a foreign language. Dyslexia. 2000; 6(1):72-82. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0909(200001/03)6:1<72::aid-dys162>3.0.co;2-b

https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0909(200001/03)6:1<72::AID-DYS162>3.0.CO;2-B [DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0909(200001/03)6:13.0.CO;2-B]

14. Blaufarb H. A demonstration of verbal abstracting ability in chronic schizophrenics under enriched stimulus and instructional conditions. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1962; 26(5):471–5. doi: 10.1037/h0045408 [DOI:10.1037/h0045408]

15. Hamlin RM, Haywood HC, Folsom AT. Effect of enriched input on schizophrenic abstraction. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1965; 70(5):390–4. doi: 10.1037/h0022507 [DOI:10.1037/h0022507]

16. Sergi MJ, Kern RS, Mintz J, Green MF. Learning potential and the prediction of work skill acquisition in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2005; 31(1):67-72. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi007 [DOI:10.1093/schbul/sbi007]

17. Kongs SK, Thompson LL, Iverson GL, HeatonRK. Wisconsin card sorting test-64 card version (WCST-64). Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2000.

18. Zhang S, Thompson N. DIALANG: A diagnostic language assessment system (review). The Canadian Modern Language Review/La revue canadienne des langues vivantes. 2004; 61(2):290–3. doi: 10.1353/cml.2005.0011 [DOI:10.1353/cml.2005.0011]

19. Alderson JC. Diagnosing foreign language proficiency: The interface between learning and assessment. New York: Continuum; 2005

20. Aljaafreh A, Lantolf P. Negative feedback as regulation and second language learning in the zone of proximal development. The Modern Language Journal. 1994; 78(4):465-83. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1994.tb02064.x [DOI:10.1111/j.1540-4781.1994.tb02064.x]

21. Birjandi P, Ebadi S. Microgenesis in dynamic assessment of L2 learners' socio-cognitive development via web 2.0. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2012; 32:34–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.01.006 [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.01.006]

22. Swain M. Examining dialogue: another approach to content specification and to validating inferences drawn from test scores. Language Testing. 2001; 18(3):275–302. doi: 10.1177/026553220101800302 [DOI:10.1177/026553220101800302]

23. Swain M, Lapkin S. Interaction and second language learning: two adolescent french immersion students working together. The Modern language Journal. 1998; 82(3):320–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1998.tb01209.x [DOI:10.1111/j.1540-4781.1998.tb01209.x]

24. Ewald, J. Language-related episodes in an assessment context: A'small-group quiz'. Canadian Modern Language Review. 2005; 61(4):565-86. doi: 10.3138/cmlr.61.4.565 [DOI:10.3138/cmlr.61.4.565]

25. Chaika E. A linguist looks at "schizophrenic" language. Brain and Language. 1974; 1(3):257–76. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(74)90040-6 [DOI:10.1016/0093-934X(74)90040-6]

26. Feuerstein R. Instrumental enrichment. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1980. [PMCID]

27. Hogarty GE, Flesher S. Practice principles of cognitive enhancement therapy for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1999; 25(4):693–708. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033411 [DOI:10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033411]

28. Mastropieri MA, Scruggs TE, Mushinski Fulk BJ. Teaching abstract vocabulary with the keyword method. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 1990; 23(2):92–6. doi: 10.1177/002221949002300203 [DOI:10.1177/002221949002300203]

29. Humphries T, Krogh K, McKay R. Theoretical and practical considerations in the psychological and educational assessment of the student with intractable epilepsy: Dynamic assessment as an adjunct to static assessment. Seizure. 2001; 10(3):173–80. doi: 10.1053/seiz.2000.0490 [DOI:10.1053/seiz.2000.0490]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |