Volume 15, Issue 4 (December 2017)

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2017, 15(4): 359-366 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ghodousi N, Sajedi F, Mirzaie H, Rezasoltani P. The Effectiveness of Cognitive-Behavioral Play Therapy on Externalizing Behavior Problems Among Street and Working Children. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2017; 15 (4) :359-366

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-693-en.html

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-693-en.html

1- Department of Psychology and Education of Exceptional Children, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Occupational Therapy, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Biostatistics, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Occupational Therapy, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Biostatistics, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 517 kb]

(3830 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (8926 Views)

Full-Text: (3809 Views)

1. Introduction

The United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) refers to children aged under 18 years spending most of their lifetime on low-paying jobs without supervision by adults as street children. In this regard, two basic elements of presence and life on streets and work for survival are taken into account as the factors to include such individuals as street children [1]. Moreover, determining the exact number of street children is impossible according to the estimates released by the UNICEF, but such figures approximately reach to about tens of millions children throughout the world [2]. The age range of these children in developing countries falls under 8 years, although in developed countries the range is above 12 years [3].

These children suffer from various problems such as difficulties in cognitive skills [4], sexual abuse [5], substance abuse [6], family problems including domestic violence, addiction, parental separation, poverty, economic challenges [7], abnormal behaviors such as distraction, withdrawal, and aggression [8], as well as anxiety and depression [9].

Study by Ghasemzadeh (2003) on street and working children in Iran showed that the amount of externalizing behavior problems such as aggression and violence was equal to 80%, willingness to commit delinquency was 55%, inattention to rights of others was equal to 54%, revenge and hostility was about 58%, and addiction was equal to 37%. Also, the amounts of theft and drug dealing were 50% and 41%, respectively [10]. These behavioral problems can bring about complications for such children in future and they are similarly considered as the factors affecting children to resort to delinquency and criminal behaviors in adulthood. Moreover, these children might experience the risks of peer exclusion as well as academic failure [11].

In order to treat behavioral problems in children, various therapy methods have been employed. Accordingly, numerous studies have also confirmed the effectiveness of therapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy [12], narrative exposure therapy [13], and play therapy [14] on behavioral problems of children.

Play therapy is one of the therapy methods used to treat behavioral problems of children. It is noteworthy that playing makes a connection between a child’s inner and outer worlds. In addition, children can control things and external stuff through games and also express their negative thoughts and feelings during the playing process [15]. There are various approaches to play therapy, chosen according to the context in which the intervention takes place, the theoretical view of therapists, as well as the needs of children. One of these approaches is cognitive-behavioral play therapy that integrates behavioral and cognitive interventions in the paradigm of play therapy [16]. Within this play therapy approach, inconsistent thoughts associated with behavioral problems in children are identified and then changed. There are similar changes in children’s cognitions to substitute them with more adaptive thoughts and behaviors [17]. Furthermore, various studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral play therapy on externalizing problems such as social maladjustment [18], oppositional defiance, and aggression [19] among children.

In essence, several studies implicated the importance of cognitive-behavioral play therapy in the effective treatment of behavioral problems and enhancement of capabilities among children. Considering the prevalence of behavioral problems of street children, there is a need for early and effective intervention to prevent more problems and challenges in adulthood. Previous studies investigating the impact of cognitive-behavioral play therapy have not shed any light on externalizing behavior problems among street children. Therefore, this study was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral play therapy on externalizing behavior problems among street and working children.

2. Methods

The present study is an experimental one with a pre- and posttest control group design. The statistical population of the present study included all street and working girls in Kiana Sociocultural Group Center in the city of Karaj in 2016-2017. Those girls had been identified by social workers, and they were also studying, participating in educational programs, and receiving the relevant services. In order to observe the ethical considerations, the objectives and the steps of the present study were explained to the officials of the Center and written informed consent forms were also obtained. Then, Achenbach’s Teacher Report Form (TRF) for all girls aged 7-10 years were completed by teachers of 4 grades. All the teachers were holding bachelor’s degrees. The children had also attended for at least 6 months in the classes held by those teachers lasting 4 days a week and for 4 hours per day. The girls recruited for this study were living in the city of Karaj; they were involved in false jobs to support their families economically; they were endowed with normal intelligence quotients; and they had also obtained T-scores equal to 63 and above from the TRF. However, the girls whose parents, adopters, or employers did not give any consent for their participation in play therapy sessions as well as children affected with chronic physical illnesses (based on child’s medical records), substance abuse or disability (physical disabilities, blindness, deafness, etc.) were excluded from the present study.

In total, 40 children were randomly selected and placed in 2 groups of intervention and control (20 individuals in each group) based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The children in the intervention group were divided into 4 groups of 5 girls who participated in play therapy sessions. These sessions lasted over 6 weeks and 2 one-hour sessions per week in the playroom of the Center. In each session, 3 games were played with different objectives based on children’s age (7 to 10 years). The trial approved by the ethical committee and the ethical code was IR.USWR.REC.1395.209.

Research Instrument: To collect the data, the TRF was used as one of the forms in the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA), which had been developed in 1987 by Achenbach and Mcgonany. The questionnaire measures emotional-behavioral problems as well as academic and social abilities, and competencies from the perspective of teachers of children aged 6-18 years. One section of this form is related to syndromes comprised of 113 major items and 8 sub-items on a 3-point scale (0=false; 1=somewhat or sometimes true; 2=completely or mostly true) measuring behavioral, emotional, and social problems in children. This section called the empirically-based measures is comprised of anxiety/depression, withdrawal/depression, and somatic complaints forming up internalizing behavior problems and law-breaking behavior, as well as aggression representing externalizing problems. In the present study, the internalizing problems through empirically-based measure were employed. The scores for internalizing behavior problems were also obtained by adding the scores for aggressive behavior scale and law-breaking one. Then, the raw scores were converted to T-scores and the clinical domains, boundaries, or norms of each child were determined by referring to the Iranian Social Norms Table based on age and gender.

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the empirically-based measures in the TRF were in a range from 0.71 to 0.95 and they were reported between 0.62 and 0.92 for the measures based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). In addition, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the age group of 6-11 years in the TRF in its overall compliance was equal to 0.85 and they were 0.83, 0.84, 0.76, 0.78, 0.76, 0.95 (0.92 and 0.92), 0.77, and 0.94 in the empirically-based measures including anxiety/depression, withdrawal/depression, somatic complaints, social problems, thought problems, attention problems (lack of attention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity), law-breaking behavior, and aggression, respectively. Moreover, the coefficients for the internalizing problems, externalizing problems, and the overall ones were equal to 0.90, 0.81, and 0.85, respectively. The cut-off point in the externalizing scale refers to T-scores above 63 in the clinical range. The T-scores equal to 60 to 63 or tenth to the sixteenth percentile range form up the borderline and the T-scores lower than 60 are placed in the normal range [20].

Cognitive-behavioral play therapy intervention package

The cognitive-behavioral play therapy intervention package was designed by Mirzaei (2016), a specialist in this field, through the researcher’s participation in cognitive-behavioral play therapy workshop held by Tahmasian (2016) as well as the use of library resources [21, 22]. The games were performed in group and they were also designed to have different difficulty levels. The intervention group consisted of 4 groups of 5 children who participated in the play therapy sessions. The games were set based on the age range of children and the objectives of the study. Play therapy sessions were performed by the psychologist.

Session one

Session One includes playing with toys in playroom. The purpose of this session was to familiarize children with the playroom and its laws.

Session two

Session Two includes group painting, darts, and making emotion masks. This session aimed at enhancing interpersonal communication skills, broadening knowledge of the body members, discharging excitement, increasing accuracy, boosting subtle hand movements, coordinating eye-hand movements, as well as recognizing emotions and physical protests.

Session three

Session Three includes building pyramid of glasses, playing with chairs, and making emotional stories using star page. The purpose of this session was to increase social skills, provide eye-hand cooperation, reinforce listening ability, release excitement, strengthen muscles, manage and control anger, and teach new words.

Session four

Session Four includes cooking, bowling, and completing unfinished sentences via finger dolls. This session aimed at increasing interpersonal communication skills, enhancing power of imagination, increasing verbal and nonverbal skills, coordinating eye-hand movements, reinforcing large motor skills, strengthening laterality, having true dialogues, paying respect to each other, increasing self-confidence, and knowing about physical characteristics and appearance.

Session five

Session five includes making words with letter puzzle, running together, and making clay sculptures. The purpose of this session was to reinforce auditory memory, provide grounds for reading and writing skills, reinforce letter recognition skills, discharge excitement, increase attention and concentration, boost muscle coordination, reduce stress, reinforce power of imagination, and raise self-confidence.

Session six

Session six includes cutting papers and building a jungle, playing golf, and puppet theater. This session aimed at fostering fine motor hand movements, providing eye-hand coordination, increasing attention and concentration, boosting power of imagination and creativity, adding to accuracy, improving anger control skills, nurturing intellectual concepts, as well as raising verbal skills and problem-solving abilities.

Session seven

Session seven includes doctor-and-patient game, mazes and running, and thrilling tower. The purpose of this game was to increase social skills, enhance communication skills, foster empathy, release excitement, provide physical-motor coordination, boost memory, and also increase attention span.

Session eight

Session eight includes finding differences, bowling, Ronnie Park 18. This session aimed at increasing attention, enhancing vision recognition, providing eye-hand coordination, strengthening large motor skills, reinforcing laterality, and discharging excitement.

Session nine

Session nine includes making sentences with words, angry balloons, and sand tray. The purpose of this session was to improve reading skills and sentence-making, foster mental concepts, increase positive self-talk skills, teach how to discharge anger, increase selective attention, have relaxation, discharge excitement, grow and foster creativity, raise and promote expressiveness, increase social skills, nurture spatial and geometric visualization, and strengthen sense of touch.

Session ten

Session ten includes painting with finger paints, playing golf, and pantomime. This session aimed at increasing innovation and imagination, strengthening delicate movements, reinforcing sense of touch, expressing emotions non-verbally, increasing attention and concentration, improving anger management skills, expressing oneself, learning problem-solving skills, and adding to social coping and adaptation skills.

Session eleven

Session eleven includes play-dough game, running with ball, and making up stories. The purpose of this session was to increase proprioception, improve fine movements, increase focus, raise power of creativity, nurture thinking skills, increase self-confidence, improve problem-solving skills, lower aggression, teach problem-solving skills, learn new and alternative solutions to tackle problems, and enhance verbal communication ability.

Session twelve

Session twelve includes making clay sculptures and drawing dummy figures. This session aimed at reviewing the measures taken during all the play therapy sessions. During the play therapy sessions children’s self-awareness, self-perception, and self-control skills were increased through cognitive interventions such as self-education, diagnosis of cognitive errors, cognitive reconstruction, and behavioral interventions such as systematic desensitization, positive reinforcement, and extinguishing. In addition, children were helped to identify their negative thoughts and beliefs through these games and through the process of self-reflection, replace the new solutions and accept their weaknesses and strengths.

After implementing the tests and holding the play therapy sessions, the results of the data obtained from both groups in both pre- and posttest steps were analyzed in the form of descriptive and inferential indices. To analyze the data, the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was also used and statistical operations were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 21 software.

3. Results

The subjects of this study were all female and aged between 7 and 10 years with a mean age of 8.35 (SD:

The United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) refers to children aged under 18 years spending most of their lifetime on low-paying jobs without supervision by adults as street children. In this regard, two basic elements of presence and life on streets and work for survival are taken into account as the factors to include such individuals as street children [1]. Moreover, determining the exact number of street children is impossible according to the estimates released by the UNICEF, but such figures approximately reach to about tens of millions children throughout the world [2]. The age range of these children in developing countries falls under 8 years, although in developed countries the range is above 12 years [3].

These children suffer from various problems such as difficulties in cognitive skills [4], sexual abuse [5], substance abuse [6], family problems including domestic violence, addiction, parental separation, poverty, economic challenges [7], abnormal behaviors such as distraction, withdrawal, and aggression [8], as well as anxiety and depression [9].

Study by Ghasemzadeh (2003) on street and working children in Iran showed that the amount of externalizing behavior problems such as aggression and violence was equal to 80%, willingness to commit delinquency was 55%, inattention to rights of others was equal to 54%, revenge and hostility was about 58%, and addiction was equal to 37%. Also, the amounts of theft and drug dealing were 50% and 41%, respectively [10]. These behavioral problems can bring about complications for such children in future and they are similarly considered as the factors affecting children to resort to delinquency and criminal behaviors in adulthood. Moreover, these children might experience the risks of peer exclusion as well as academic failure [11].

In order to treat behavioral problems in children, various therapy methods have been employed. Accordingly, numerous studies have also confirmed the effectiveness of therapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy [12], narrative exposure therapy [13], and play therapy [14] on behavioral problems of children.

Play therapy is one of the therapy methods used to treat behavioral problems of children. It is noteworthy that playing makes a connection between a child’s inner and outer worlds. In addition, children can control things and external stuff through games and also express their negative thoughts and feelings during the playing process [15]. There are various approaches to play therapy, chosen according to the context in which the intervention takes place, the theoretical view of therapists, as well as the needs of children. One of these approaches is cognitive-behavioral play therapy that integrates behavioral and cognitive interventions in the paradigm of play therapy [16]. Within this play therapy approach, inconsistent thoughts associated with behavioral problems in children are identified and then changed. There are similar changes in children’s cognitions to substitute them with more adaptive thoughts and behaviors [17]. Furthermore, various studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral play therapy on externalizing problems such as social maladjustment [18], oppositional defiance, and aggression [19] among children.

In essence, several studies implicated the importance of cognitive-behavioral play therapy in the effective treatment of behavioral problems and enhancement of capabilities among children. Considering the prevalence of behavioral problems of street children, there is a need for early and effective intervention to prevent more problems and challenges in adulthood. Previous studies investigating the impact of cognitive-behavioral play therapy have not shed any light on externalizing behavior problems among street children. Therefore, this study was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral play therapy on externalizing behavior problems among street and working children.

2. Methods

The present study is an experimental one with a pre- and posttest control group design. The statistical population of the present study included all street and working girls in Kiana Sociocultural Group Center in the city of Karaj in 2016-2017. Those girls had been identified by social workers, and they were also studying, participating in educational programs, and receiving the relevant services. In order to observe the ethical considerations, the objectives and the steps of the present study were explained to the officials of the Center and written informed consent forms were also obtained. Then, Achenbach’s Teacher Report Form (TRF) for all girls aged 7-10 years were completed by teachers of 4 grades. All the teachers were holding bachelor’s degrees. The children had also attended for at least 6 months in the classes held by those teachers lasting 4 days a week and for 4 hours per day. The girls recruited for this study were living in the city of Karaj; they were involved in false jobs to support their families economically; they were endowed with normal intelligence quotients; and they had also obtained T-scores equal to 63 and above from the TRF. However, the girls whose parents, adopters, or employers did not give any consent for their participation in play therapy sessions as well as children affected with chronic physical illnesses (based on child’s medical records), substance abuse or disability (physical disabilities, blindness, deafness, etc.) were excluded from the present study.

In total, 40 children were randomly selected and placed in 2 groups of intervention and control (20 individuals in each group) based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The children in the intervention group were divided into 4 groups of 5 girls who participated in play therapy sessions. These sessions lasted over 6 weeks and 2 one-hour sessions per week in the playroom of the Center. In each session, 3 games were played with different objectives based on children’s age (7 to 10 years). The trial approved by the ethical committee and the ethical code was IR.USWR.REC.1395.209.

Research Instrument: To collect the data, the TRF was used as one of the forms in the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA), which had been developed in 1987 by Achenbach and Mcgonany. The questionnaire measures emotional-behavioral problems as well as academic and social abilities, and competencies from the perspective of teachers of children aged 6-18 years. One section of this form is related to syndromes comprised of 113 major items and 8 sub-items on a 3-point scale (0=false; 1=somewhat or sometimes true; 2=completely or mostly true) measuring behavioral, emotional, and social problems in children. This section called the empirically-based measures is comprised of anxiety/depression, withdrawal/depression, and somatic complaints forming up internalizing behavior problems and law-breaking behavior, as well as aggression representing externalizing problems. In the present study, the internalizing problems through empirically-based measure were employed. The scores for internalizing behavior problems were also obtained by adding the scores for aggressive behavior scale and law-breaking one. Then, the raw scores were converted to T-scores and the clinical domains, boundaries, or norms of each child were determined by referring to the Iranian Social Norms Table based on age and gender.

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the empirically-based measures in the TRF were in a range from 0.71 to 0.95 and they were reported between 0.62 and 0.92 for the measures based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). In addition, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the age group of 6-11 years in the TRF in its overall compliance was equal to 0.85 and they were 0.83, 0.84, 0.76, 0.78, 0.76, 0.95 (0.92 and 0.92), 0.77, and 0.94 in the empirically-based measures including anxiety/depression, withdrawal/depression, somatic complaints, social problems, thought problems, attention problems (lack of attention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity), law-breaking behavior, and aggression, respectively. Moreover, the coefficients for the internalizing problems, externalizing problems, and the overall ones were equal to 0.90, 0.81, and 0.85, respectively. The cut-off point in the externalizing scale refers to T-scores above 63 in the clinical range. The T-scores equal to 60 to 63 or tenth to the sixteenth percentile range form up the borderline and the T-scores lower than 60 are placed in the normal range [20].

Cognitive-behavioral play therapy intervention package

The cognitive-behavioral play therapy intervention package was designed by Mirzaei (2016), a specialist in this field, through the researcher’s participation in cognitive-behavioral play therapy workshop held by Tahmasian (2016) as well as the use of library resources [21, 22]. The games were performed in group and they were also designed to have different difficulty levels. The intervention group consisted of 4 groups of 5 children who participated in the play therapy sessions. The games were set based on the age range of children and the objectives of the study. Play therapy sessions were performed by the psychologist.

Session one

Session One includes playing with toys in playroom. The purpose of this session was to familiarize children with the playroom and its laws.

Session two

Session Two includes group painting, darts, and making emotion masks. This session aimed at enhancing interpersonal communication skills, broadening knowledge of the body members, discharging excitement, increasing accuracy, boosting subtle hand movements, coordinating eye-hand movements, as well as recognizing emotions and physical protests.

Session three

Session Three includes building pyramid of glasses, playing with chairs, and making emotional stories using star page. The purpose of this session was to increase social skills, provide eye-hand cooperation, reinforce listening ability, release excitement, strengthen muscles, manage and control anger, and teach new words.

Session four

Session Four includes cooking, bowling, and completing unfinished sentences via finger dolls. This session aimed at increasing interpersonal communication skills, enhancing power of imagination, increasing verbal and nonverbal skills, coordinating eye-hand movements, reinforcing large motor skills, strengthening laterality, having true dialogues, paying respect to each other, increasing self-confidence, and knowing about physical characteristics and appearance.

Session five

Session five includes making words with letter puzzle, running together, and making clay sculptures. The purpose of this session was to reinforce auditory memory, provide grounds for reading and writing skills, reinforce letter recognition skills, discharge excitement, increase attention and concentration, boost muscle coordination, reduce stress, reinforce power of imagination, and raise self-confidence.

Session six

Session six includes cutting papers and building a jungle, playing golf, and puppet theater. This session aimed at fostering fine motor hand movements, providing eye-hand coordination, increasing attention and concentration, boosting power of imagination and creativity, adding to accuracy, improving anger control skills, nurturing intellectual concepts, as well as raising verbal skills and problem-solving abilities.

Session seven

Session seven includes doctor-and-patient game, mazes and running, and thrilling tower. The purpose of this game was to increase social skills, enhance communication skills, foster empathy, release excitement, provide physical-motor coordination, boost memory, and also increase attention span.

Session eight

Session eight includes finding differences, bowling, Ronnie Park 18. This session aimed at increasing attention, enhancing vision recognition, providing eye-hand coordination, strengthening large motor skills, reinforcing laterality, and discharging excitement.

Session nine

Session nine includes making sentences with words, angry balloons, and sand tray. The purpose of this session was to improve reading skills and sentence-making, foster mental concepts, increase positive self-talk skills, teach how to discharge anger, increase selective attention, have relaxation, discharge excitement, grow and foster creativity, raise and promote expressiveness, increase social skills, nurture spatial and geometric visualization, and strengthen sense of touch.

Session ten

Session ten includes painting with finger paints, playing golf, and pantomime. This session aimed at increasing innovation and imagination, strengthening delicate movements, reinforcing sense of touch, expressing emotions non-verbally, increasing attention and concentration, improving anger management skills, expressing oneself, learning problem-solving skills, and adding to social coping and adaptation skills.

Session eleven

Session eleven includes play-dough game, running with ball, and making up stories. The purpose of this session was to increase proprioception, improve fine movements, increase focus, raise power of creativity, nurture thinking skills, increase self-confidence, improve problem-solving skills, lower aggression, teach problem-solving skills, learn new and alternative solutions to tackle problems, and enhance verbal communication ability.

Session twelve

Session twelve includes making clay sculptures and drawing dummy figures. This session aimed at reviewing the measures taken during all the play therapy sessions. During the play therapy sessions children’s self-awareness, self-perception, and self-control skills were increased through cognitive interventions such as self-education, diagnosis of cognitive errors, cognitive reconstruction, and behavioral interventions such as systematic desensitization, positive reinforcement, and extinguishing. In addition, children were helped to identify their negative thoughts and beliefs through these games and through the process of self-reflection, replace the new solutions and accept their weaknesses and strengths.

After implementing the tests and holding the play therapy sessions, the results of the data obtained from both groups in both pre- and posttest steps were analyzed in the form of descriptive and inferential indices. To analyze the data, the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was also used and statistical operations were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 21 software.

3. Results

The subjects of this study were all female and aged between 7 and 10 years with a mean age of 8.35 (SD:

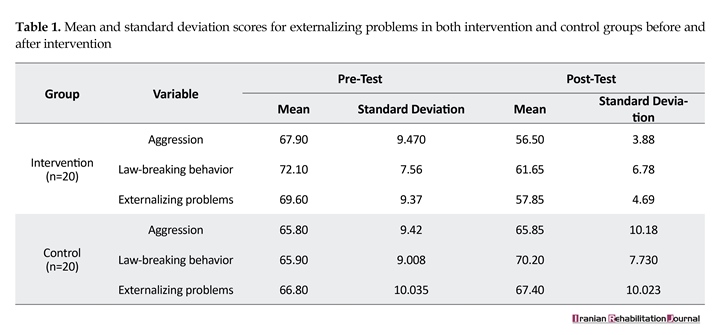

1.039) and 8.15 years (SD: 1.118) in the intervention and control groups, respectively. They were also enrolled in grades first to fourth. The descriptive indices for externalizing problems between both intervention and control groups in the pre- and posttest steps are shown in Table 1. The results presented in Table 1 showed that the mean for externalizing behavior problems in the intervention group declined in the posttest step while the mean for externalizing problems in the control group slightly increased in this respect.

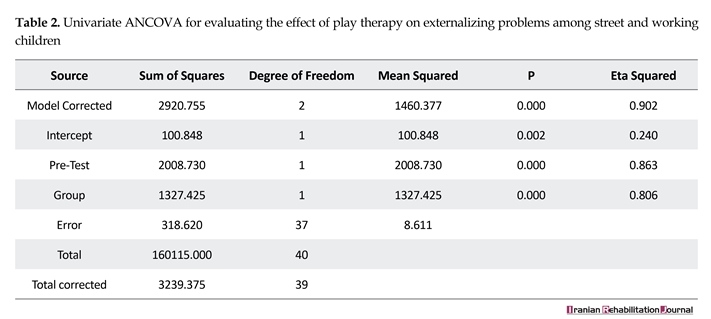

To compare the differences between groups in both pre- and posttest, the ANCOVA was used and the results are illustrated in Table 2. Table 2 illustrated a significant decrease in the externalizing problems in the intervention group (P<0.01). According to the eta squared, it was revealed that 80% of the changes in the externalizing problems among children were due to participating in cognitive-behavioral play therapy sessions.

4. Discussion

The present study suggested that cognitive-behavioral play therapy was effective in reducing externalizing behavior problems among street and working children aged 7-10 years. Several studies have examined the effect of play therapy on behavioral problems among children. For example, Dadsetan et al. (2010) showed that child-directed play therapy had impacts on reducing aggression among children suffering from aggressive and externalizing problems. In this study, 16 sessions of play therapy were held for 10 children who had received high scores from the TRF and the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL). The findings in this study suggested that externalizing problems, particularly aggression among children had decreased [23].

Another study conducted by Karcher and Lewis (2002) on 8 boys and 11 girls aged 9-17 years and 8-12 years, respectively, in which the children were allowed to participate in play therapy sessions under the guidance of a therapist. The results indicated that play therapy was effective in lowering aggression and antisocial behaviors among children [24]. In a separate study carried out by Dogra and Veeraraghavan (1999), 2 groups of 10 children aged 8-12 years and suffering from aggressive conduct disorder were recruited. Those children and their parents attended in 8 weekly sessions of play therapy and counseling. The results indicated that play therapy had an effect on decreasing symptoms of conduct disorder and aggression in children [25]. Moreover; in a case study by Paone and Douma (2008), the effectiveness of play therapy on behavioral problems in children aged 7 years and suffering from intermittent explosive disorder were investigated. The children participated in 16 play therapy sessions and the results revealed that behavioral problems such as aggression among children had declined [26].

In another investigation by Barzegar et al. (2013), 15 children who had scored high on the CBCL were selected and randomly placed in the intervention group. They also participated in 16 sessions of play therapy. The results of the study showed that the externalizing behavior problems, aggression, and disobeying rules had reduced in children [27]. Safari et al. (2014) also investigated the effects of cognitive-behavioral play therapy on behavioral symptoms among disobedient students. In their study, 30 children suffering from oppositional defiant disorder according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) were selected and then randomly divided into 2 groups of intervention and control. The intervention group took part in 10 cognitive-behavioral play therapy sessions. The results of this study revealed that behavioral problems in children had decreased [28]. In summary, the above-mentioned studies suggest that play therapy is considered as one of the effective therapy methods to deal with and reduce externalizing behavioral problems among children. The outcome of the present study is also consistent with the investigations mentioned above.

Living and working on streets as well as homelessness expose children to types of deviations and antisocial behaviors [29]. Of note, individuals who are aggressive during childhood tend to continue their aggression during adulthood also [30]. The incidence of these aggressive behaviors can cause the child to be abandoned by their peers. In addition, people affected with aggression may suffer from depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem [31]. Thus, play therapy can aid such children to express their negative thoughts and feelings through games [32]. In addition, children can acquire numerous skills during the game process. Moreover, games assist children to understand the world around them and thereby gain experiences in this respect [33]. Therefore, games can be used to deal with problems among street children.

Given the extensive and ever-increasing phenomena of street and working children, therapists can make use of such therapy methods and tackle such problems to prevent their occurrence to some extent in the future. However, this method has limitations including the restricted number of participants and its confinement to the city of Karaj despite its growth in all cities across Iran. Moreover, the given questionnaires used in the present study were completed by teachers with less knowledge about the children due to having no access to their parents or their parents’ death and illiteracy. Another limitation of the present research is the use of single measurement tool.

It is suggested that future research should be done on street boys also. In addition, a follow-up test should be conducted to assess the sustainability of the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral play therapy. It is also suggested that this cognitive-behavioral approach could be employed by psychologists working in centers with these kinds of children.

5. Conclusion

It seems that one of the effective ways to lessen externalizing behavior problems among street and working children is cognitive-behavioral play therapy; therefore, coaches and teachers are recommended to make use of this method to lower the behavioral problems of such children.

Acknowledgments

This study was derived from a MSc. thesis in Psychology and Education of Exceptional Children at the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran. We hereby express our gratitude to Kiana Social-Cultural Group Center and its officials as well as those children who helped the researchers in this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

[1]UNICEF. The state of the world's children 2006: Excluded and invisible. New York: UNICEF; 2005.

[2]De Benítez ST. State of the world's street children: violence: Consortium for Street Children. London: Consortium for Street Children; 2007.

[3]Ross ML. Does oil hinder democracy? World Politics. 2001; 53(3):325-61.

[4]Bassuk EL, Gallagher EM. The impact of homelessness on children. Children and Youth Services Review. 1990; 14(1):19-33.

[5]Ahmadkhaniha HR, Shariat SV, Torkaman-nejad S, Moghadam MMH. The frequency of sexual abuse and depression in a sample of street children of one of deprived districts of Tehran. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2007; 16(4):23–35. doi: 10.1300/j070v16n04_02

[6]Dejman M, Vameghi M, Dejman F, Roshanfekr P, Rafiey H, Forouzan AS, et al. Substance use among street children in Tehran, Iran. Frontiers in Public Health. 2015; 3:279. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00279

[7]Vameghi M, Sajadi H, Rafiey H, Rashidian A. The socioeconomic status of street children in Iran: A systematic review on studies over a recent decade. Children & Society. 2012; 28(5):352–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1099-0860.2012.00456.x

[8]Molnar JM, Rath WR, Klein TP. Constantly compromised: Theimpact of homelessness on children. Journal of Social Issues. 1990; 46(4):109–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1990.tb01801.x

[9]Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, Bao WN. Depressive symptoms and co-occurring depressive symptoms, substance abuse, and conduct problems among runaway and homeless adolescents. Child Development. 2000; 71(3):721–32. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00181

[10]Ghasemzadeh F. [Street children in Tehran (Persian)]. Social Welfare. 2003; 2(7):249-63.

[11]McKee L, Colletti C, Rakow A, Jones DJ, Forehand R. Parenting and child externalizing behaviors: Are the associations specific or diffuse? Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2008; 13(3):201–15. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2008.03.005

[12]Sung M, Ooi YP, Goh TJ, Pathy P, Fung DSS, Ang RP, et al. Effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy on anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2011; 42(6):634–49. doi: 10.1007/s10578-011-0238-1

[13]Ruf M, Schauer M, Neuner F, Catani C, Schauer E, Elbert T. Narrative exposure therapy for 7- to 16-year-olds: A randomized controlled trial with traumatized refugee children. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010; 23(4):437–45. doi: 10.1002/jts.20548

[14]Baggerly J. The effects of child-centered group play therapy on self-concept, depression, and anxiety of children who are homeless. International Journal of Play Therapy. 2004; 13(2):31–51. doi: 10.1037/h0088889

[15]Rafati F, Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi M, Pishyareh E, Mirzaei H, Biglarian A. [Effectiveness of group play therapy on the communication of 5-8 years old children with high functioning autism (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2016; 17(3):200-211.

[16]Knell SM, Moore DJ. Cognitive-behavioral play therapy in the treatment of encopresis. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1990; 19(1):55–60. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp1901_7

[17]Ray D. Supervision of basic and advanced skills in play therapy. Journal of Professional Counseling: Practice, Theory & Research. 2004; 32(2):28-41.

[18]Nasab MA, Mohammadi MA, Mazloomi A. Effectiveness of group play therapy through cognitive - behavioral method on social adjustment of children with behavioral disorder. Kuwait Chapter of Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review. 2014; 3(12):356–62. doi: 10.12816/0018839

[19]Akbari B, Rahmati F. [The efficacy of cognitive behavioral play therapy on the reduction of aggression in preschool children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (Persian)]. Quarterly Journal of Child Mental Health. 2015; 2(2):93-100

[20]Minaei A. [Adaptation and standardization of Child Behavior Checklist, youth self-report, and teacher report forms (Persian)]. Research on Exceptional Children. 2006; 6(1):529-58.

[21]Stallard P. Think good-feel good: A cognitive behaviour therapy workbook for children and young people. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2003.

[22]Kaduson H, Schaefer C. 101 favorite play therapy techniques. Lanham, Maryland: Jason Aronson; 2010.

[23]Dadsetan P, Bayat M, Asgari A. Effectiveness of child-centered play therapy on children's externalizing problems reduction. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2010; 3(4):257-64.

[24]Karcher MJ, Lewis SS. Pair counseling: The effects of a dyadic developmental play therapy on interpersonal understanding and externalizing behaviors. International Journal of Play Therapy. 2002; 11(1):19–41. doi: 10.1037/h0088855

[25]Dogra A, Veeraraghavan V. A study of psychological intervention of children with aggressive conduct disorder. Indian Journal of Clinical Psycholog. 1994; 21(1):28-32.

[26]Paone TR, Douma KB. Child-centered play therapy with a seven-year-old boy diagnosed with intermittent explosive disorder. International Journal of Play Therapy. American 2009; 18(1):31–44. doi: 10.1037/a0013938

[27]Barzegar Z, Pourmohamadrezatajrishi M, Behnia F. The effectiveness of playing on externalizing problems in preschool children with behavioral problems. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2012; 6(4):347-54.

[28]Safary S, Faramarzi S, Abedi A. [Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral play therapy on behavioral symptoms of disobedient students (Persian)]. Urmia Medical Journal. 2014; 25(3):258-67.

[29]Huang CY, Menke EM. School-aged homeless sheltered children's stressors and coping behaviors. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2001; 16(2):102-09. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2001.23153

[30]Ladd GW, Burgess KB. Charting the relationship trajectories of aggressive, withdrawn, and aggressive/withdrawn children during early grade school. Child Development. 1999; 70(4):910–29. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00066

[31]Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development. 1995; 66(3):710. doi: 10.2307/1131945

[32]Han Y, Lee Y, Suh JH. Effects of a sandplay therapy program at a childcare center on children with externalizing behavioral problems. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 2017; 52:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2016.09.008

[33]Brestan EV, Eyberg SM. Effective psychosocial treatments of conduct-disordered children and adolescents: 29 years, 82 studies, and 5,272 kids. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1998; 27(2):180–9. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2702_5

To compare the differences between groups in both pre- and posttest, the ANCOVA was used and the results are illustrated in Table 2. Table 2 illustrated a significant decrease in the externalizing problems in the intervention group (P<0.01). According to the eta squared, it was revealed that 80% of the changes in the externalizing problems among children were due to participating in cognitive-behavioral play therapy sessions.

4. Discussion

The present study suggested that cognitive-behavioral play therapy was effective in reducing externalizing behavior problems among street and working children aged 7-10 years. Several studies have examined the effect of play therapy on behavioral problems among children. For example, Dadsetan et al. (2010) showed that child-directed play therapy had impacts on reducing aggression among children suffering from aggressive and externalizing problems. In this study, 16 sessions of play therapy were held for 10 children who had received high scores from the TRF and the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL). The findings in this study suggested that externalizing problems, particularly aggression among children had decreased [23].

Another study conducted by Karcher and Lewis (2002) on 8 boys and 11 girls aged 9-17 years and 8-12 years, respectively, in which the children were allowed to participate in play therapy sessions under the guidance of a therapist. The results indicated that play therapy was effective in lowering aggression and antisocial behaviors among children [24]. In a separate study carried out by Dogra and Veeraraghavan (1999), 2 groups of 10 children aged 8-12 years and suffering from aggressive conduct disorder were recruited. Those children and their parents attended in 8 weekly sessions of play therapy and counseling. The results indicated that play therapy had an effect on decreasing symptoms of conduct disorder and aggression in children [25]. Moreover; in a case study by Paone and Douma (2008), the effectiveness of play therapy on behavioral problems in children aged 7 years and suffering from intermittent explosive disorder were investigated. The children participated in 16 play therapy sessions and the results revealed that behavioral problems such as aggression among children had declined [26].

In another investigation by Barzegar et al. (2013), 15 children who had scored high on the CBCL were selected and randomly placed in the intervention group. They also participated in 16 sessions of play therapy. The results of the study showed that the externalizing behavior problems, aggression, and disobeying rules had reduced in children [27]. Safari et al. (2014) also investigated the effects of cognitive-behavioral play therapy on behavioral symptoms among disobedient students. In their study, 30 children suffering from oppositional defiant disorder according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) were selected and then randomly divided into 2 groups of intervention and control. The intervention group took part in 10 cognitive-behavioral play therapy sessions. The results of this study revealed that behavioral problems in children had decreased [28]. In summary, the above-mentioned studies suggest that play therapy is considered as one of the effective therapy methods to deal with and reduce externalizing behavioral problems among children. The outcome of the present study is also consistent with the investigations mentioned above.

Living and working on streets as well as homelessness expose children to types of deviations and antisocial behaviors [29]. Of note, individuals who are aggressive during childhood tend to continue their aggression during adulthood also [30]. The incidence of these aggressive behaviors can cause the child to be abandoned by their peers. In addition, people affected with aggression may suffer from depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem [31]. Thus, play therapy can aid such children to express their negative thoughts and feelings through games [32]. In addition, children can acquire numerous skills during the game process. Moreover, games assist children to understand the world around them and thereby gain experiences in this respect [33]. Therefore, games can be used to deal with problems among street children.

Given the extensive and ever-increasing phenomena of street and working children, therapists can make use of such therapy methods and tackle such problems to prevent their occurrence to some extent in the future. However, this method has limitations including the restricted number of participants and its confinement to the city of Karaj despite its growth in all cities across Iran. Moreover, the given questionnaires used in the present study were completed by teachers with less knowledge about the children due to having no access to their parents or their parents’ death and illiteracy. Another limitation of the present research is the use of single measurement tool.

It is suggested that future research should be done on street boys also. In addition, a follow-up test should be conducted to assess the sustainability of the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral play therapy. It is also suggested that this cognitive-behavioral approach could be employed by psychologists working in centers with these kinds of children.

5. Conclusion

It seems that one of the effective ways to lessen externalizing behavior problems among street and working children is cognitive-behavioral play therapy; therefore, coaches and teachers are recommended to make use of this method to lower the behavioral problems of such children.

Acknowledgments

This study was derived from a MSc. thesis in Psychology and Education of Exceptional Children at the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran. We hereby express our gratitude to Kiana Social-Cultural Group Center and its officials as well as those children who helped the researchers in this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

[1]UNICEF. The state of the world's children 2006: Excluded and invisible. New York: UNICEF; 2005.

[2]De Benítez ST. State of the world's street children: violence: Consortium for Street Children. London: Consortium for Street Children; 2007.

[3]Ross ML. Does oil hinder democracy? World Politics. 2001; 53(3):325-61.

[4]Bassuk EL, Gallagher EM. The impact of homelessness on children. Children and Youth Services Review. 1990; 14(1):19-33.

[5]Ahmadkhaniha HR, Shariat SV, Torkaman-nejad S, Moghadam MMH. The frequency of sexual abuse and depression in a sample of street children of one of deprived districts of Tehran. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2007; 16(4):23–35. doi: 10.1300/j070v16n04_02

[6]Dejman M, Vameghi M, Dejman F, Roshanfekr P, Rafiey H, Forouzan AS, et al. Substance use among street children in Tehran, Iran. Frontiers in Public Health. 2015; 3:279. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00279

[7]Vameghi M, Sajadi H, Rafiey H, Rashidian A. The socioeconomic status of street children in Iran: A systematic review on studies over a recent decade. Children & Society. 2012; 28(5):352–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1099-0860.2012.00456.x

[8]Molnar JM, Rath WR, Klein TP. Constantly compromised: Theimpact of homelessness on children. Journal of Social Issues. 1990; 46(4):109–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1990.tb01801.x

[9]Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, Bao WN. Depressive symptoms and co-occurring depressive symptoms, substance abuse, and conduct problems among runaway and homeless adolescents. Child Development. 2000; 71(3):721–32. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00181

[10]Ghasemzadeh F. [Street children in Tehran (Persian)]. Social Welfare. 2003; 2(7):249-63.

[11]McKee L, Colletti C, Rakow A, Jones DJ, Forehand R. Parenting and child externalizing behaviors: Are the associations specific or diffuse? Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2008; 13(3):201–15. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2008.03.005

[12]Sung M, Ooi YP, Goh TJ, Pathy P, Fung DSS, Ang RP, et al. Effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy on anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2011; 42(6):634–49. doi: 10.1007/s10578-011-0238-1

[13]Ruf M, Schauer M, Neuner F, Catani C, Schauer E, Elbert T. Narrative exposure therapy for 7- to 16-year-olds: A randomized controlled trial with traumatized refugee children. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010; 23(4):437–45. doi: 10.1002/jts.20548

[14]Baggerly J. The effects of child-centered group play therapy on self-concept, depression, and anxiety of children who are homeless. International Journal of Play Therapy. 2004; 13(2):31–51. doi: 10.1037/h0088889

[15]Rafati F, Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi M, Pishyareh E, Mirzaei H, Biglarian A. [Effectiveness of group play therapy on the communication of 5-8 years old children with high functioning autism (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2016; 17(3):200-211.

[16]Knell SM, Moore DJ. Cognitive-behavioral play therapy in the treatment of encopresis. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1990; 19(1):55–60. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp1901_7

[17]Ray D. Supervision of basic and advanced skills in play therapy. Journal of Professional Counseling: Practice, Theory & Research. 2004; 32(2):28-41.

[18]Nasab MA, Mohammadi MA, Mazloomi A. Effectiveness of group play therapy through cognitive - behavioral method on social adjustment of children with behavioral disorder. Kuwait Chapter of Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review. 2014; 3(12):356–62. doi: 10.12816/0018839

[19]Akbari B, Rahmati F. [The efficacy of cognitive behavioral play therapy on the reduction of aggression in preschool children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (Persian)]. Quarterly Journal of Child Mental Health. 2015; 2(2):93-100

[20]Minaei A. [Adaptation and standardization of Child Behavior Checklist, youth self-report, and teacher report forms (Persian)]. Research on Exceptional Children. 2006; 6(1):529-58.

[21]Stallard P. Think good-feel good: A cognitive behaviour therapy workbook for children and young people. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2003.

[22]Kaduson H, Schaefer C. 101 favorite play therapy techniques. Lanham, Maryland: Jason Aronson; 2010.

[23]Dadsetan P, Bayat M, Asgari A. Effectiveness of child-centered play therapy on children's externalizing problems reduction. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2010; 3(4):257-64.

[24]Karcher MJ, Lewis SS. Pair counseling: The effects of a dyadic developmental play therapy on interpersonal understanding and externalizing behaviors. International Journal of Play Therapy. 2002; 11(1):19–41. doi: 10.1037/h0088855

[25]Dogra A, Veeraraghavan V. A study of psychological intervention of children with aggressive conduct disorder. Indian Journal of Clinical Psycholog. 1994; 21(1):28-32.

[26]Paone TR, Douma KB. Child-centered play therapy with a seven-year-old boy diagnosed with intermittent explosive disorder. International Journal of Play Therapy. American 2009; 18(1):31–44. doi: 10.1037/a0013938

[27]Barzegar Z, Pourmohamadrezatajrishi M, Behnia F. The effectiveness of playing on externalizing problems in preschool children with behavioral problems. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2012; 6(4):347-54.

[28]Safary S, Faramarzi S, Abedi A. [Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral play therapy on behavioral symptoms of disobedient students (Persian)]. Urmia Medical Journal. 2014; 25(3):258-67.

[29]Huang CY, Menke EM. School-aged homeless sheltered children's stressors and coping behaviors. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2001; 16(2):102-09. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2001.23153

[30]Ladd GW, Burgess KB. Charting the relationship trajectories of aggressive, withdrawn, and aggressive/withdrawn children during early grade school. Child Development. 1999; 70(4):910–29. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00066

[31]Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development. 1995; 66(3):710. doi: 10.2307/1131945

[32]Han Y, Lee Y, Suh JH. Effects of a sandplay therapy program at a childcare center on children with externalizing behavioral problems. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 2017; 52:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2016.09.008

[33]Brestan EV, Eyberg SM. Effective psychosocial treatments of conduct-disordered children and adolescents: 29 years, 82 studies, and 5,272 kids. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1998; 27(2):180–9. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2702_5

Article type: Original Research Articles |

Subject:

Psychology

Received: 2017/04/23 | Accepted: 2017/08/2 | Published: 2017/12/1

Received: 2017/04/23 | Accepted: 2017/08/2 | Published: 2017/12/1

References

1. UNICEF. The state of the world's children 2006: Excluded and invisible. New York: UNICEF; 2005.

2. De Benítez ST. State of the world's street children: violence: Consortium for Street Children. London: Consortium for Street Children; 2007.

3. Ross ML. Does oil hinder democracy? World Politics. 2001; 53(3):325-61. [DOI:10.1353/wp.2001.0011]

4. Bassuk EL, Gallagher EM. The impact of homelessness on children. Children and Youth Services Review. 1990; 14(1):19-33. [DOI:10.1300/J024v14n01_03]

5. Ahmadkhaniha HR, Shariat SV, Torkaman-nejad S, Moghadam MMH. The frequency of sexual abuse and depression in a sample of street children of one of deprived districts of Tehran. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2007; 16(4):23–35. doi: 10.1300/j070v16n04_02 [DOI:10.1300/J070v16n04_02]

6. Dejman M, Vameghi M, Dejman F, Roshanfekr P, Rafiey H, Forouzan AS, et al. Substance use among street children in Tehran, Iran. Frontiers in Public Health. 2015; 3:279. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00279 [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2015.00279]

7. Vameghi M, Sajadi H, Rafiey H, Rashidian A. The socioeconomic status of street children in Iran: A systematic review on studies over a recent decade. Children & Society. 2012; 28(5):352–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1099-0860.2012.00456.x [DOI:10.1111/j.1099-0860.2012.00456.x]

8. Molnar JM, Rath WR, Klein TP. Constantly compromised: Theimpact of homelessness on children. Journal of Social Issues. 1990; 46(4):109–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1990.tb01801.x [DOI:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1990.tb01801.x]

9. Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, Bao WN. Depressive symptoms and co-occurring depressive symptoms, substance abuse, and conduct problems among runaway and homeless adolescents. Child Development. 2000; 71(3):721–32. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00181 [DOI:10.1111/1467-8624.00181]

10. Ghasemzadeh F. [Street children in Tehran (Persian)]. Social Welfare. 2003; 2(7):249-63.

11. McKee L, Colletti C, Rakow A, Jones DJ, Forehand R. Parenting and child externalizing behaviors: Are the associations specific or diffuse? Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2008; 13(3):201–15. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2008.03.005 [DOI:10.1016/j.avb.2008.03.005]

12. Sung M, Ooi YP, Goh TJ, Pathy P, Fung DSS, Ang RP, et al. Effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy on anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2011; 42(6):634–49. doi: 10.1007/s10578-011-0238-1 [DOI:10.1007/s10578-011-0238-1]

13. Ruf M, Schauer M, Neuner F, Catani C, Schauer E, Elbert T. Narrative exposure therapy for 7- to 16-year-olds: A randomized controlled trial with traumatized refugee children. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010; 23(4):437–45. doi: 10.1002/jts.20548 [DOI:10.1002/jts.20548]

14. Baggerly J. The effects of child-centered group play therapy on self-concept, depression, and anxiety of children who are homeless. International Journal of Play Therapy. 2004; 13(2):31–51. doi: 10.1037/h0088889 [DOI:10.1037/h0088889]

15. Rafati F, Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi M, Pishyareh E, Mirzaei H, Biglarian A. [Effectiveness of group play therapy on the communication of 5-8 years old children with high functioning autism (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2016; 17(3):200-211. [DOI:10.21859/jrehab-1703200]

16. Knell SM, Moore DJ. Cognitive-behavioral play therapy in the treatment of encopresis. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1990; 19(1):55–60. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp1901_7 [DOI:10.1207/s15374424jccp1901_7]

17. Ray D. Supervision of basic and advanced skills in play therapy. Journal of Professional Counseling: Practice, Theory & Research. 2004; 32(2):28-41.

18. Nasab MA, Mohammadi MA, Mazloomi A. Effectiveness of group play therapy through cognitive - behavioral method on social adjustment of children with behavioral disorder. Kuwait Chapter of Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review. 2014; 3(12):356–62. doi: 10.12816/0018839 [DOI:10.12816/0018839]

19. Akbari B, Rahmati F. [The efficacy of cognitive behavioral play therapy on the reduction of aggression in preschool children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (Persian)]. Quarterly Journal of Child Mental Health. 2015; 2(2):93-100

20. Minaei A. [Adaptation and standardization of Child Behavior Checklist, youth self-report, and teacher report forms (Persian)]. Research on Exceptional Children. 2006; 6(1):529-58.

21. Stallard P. Think good-feel good: A cognitive behaviour therapy workbook for children and young people. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2003. [PMCID]

22. Kaduson H, Schaefer C. 101 favorite play therapy techniques. Lanham, Maryland: Jason Aronson; 2010.

23. Dadsetan P, Bayat M, Asgari A. Effectiveness of child-centered play therapy on children's externalizing problems reduction. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2010; 3(4):257-64.

24. Karcher MJ, Lewis SS. Pair counseling: The effects of a dyadic developmental play therapy on interpersonal understanding and externalizing behaviors. International Journal of Play Therapy. 2002; 11(1):19–41. doi: 10.1037/h0088855 [DOI:10.1037/h0088855]

25. Dogra A, Veeraraghavan V. A study of psychological intervention of children with aggressive conduct disorder. Indian Journal of Clinical Psycholog. 1994; 21(1):28-32.

26. Paone TR, Douma KB. Child-centered play therapy with a seven-year-old boy diagnosed with intermittent explosive disorder. International Journal of Play Therapy. American 2009; 18(1):31–44. doi: 10.1037/a0013938 [DOI:10.1037/a0013938]

27. Barzegar Z, Pourmohamadrezatajrishi M, Behnia F. The effectiveness of playing on externalizing problems in preschool children with behavioral problems. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2012; 6(4):347-54.

28. Safary S, Faramarzi S, Abedi A. [Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral play therapy on behavioral symptoms of disobedient students (Persian)]. Urmia Medical Journal. 2014; 25(3):258-67.

29. Huang CY, Menke EM. School-aged homeless sheltered children's stressors and coping behaviors. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2001; 16(2):102-09. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2001.23153 [DOI:10.1053/jpdn.2001.23153]

30. Ladd GW, Burgess KB. Charting the relationship trajectories of aggressive, withdrawn, and aggressive/withdrawn children during early grade school. Child Development. 1999; 70(4):910–29. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00066 [DOI:10.1111/1467-8624.00066]

31. Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development. 1995; 66(3):710. doi: 10.2307/1131945 [DOI:10.2307/1131945]

32. Han Y, Lee Y, Suh JH. Effects of a sandplay therapy program at a childcare center on children with externalizing behavioral problems. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 2017; 52:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2016.09.008 [DOI:10.1016/j.aip.2016.09.008]

33. Brestan EV, Eyberg SM. Effective psychosocial treatments of conduct-disordered children and adolescents: 29 years, 82 studies, and 5,272 kids. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1998; 27(2):180–9. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2702_5 [DOI:10.1207/s15374424jccp2702_5]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |