Volume 17, Issue 4 (December 2019)

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2019, 17(4): 351-358 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Sadri Damirch E, Esmaeili Ghazivaoloii F, Fathi D, Mehraban S, Ahmadboukani S. Effectiveness of Group Psychotherapy Based on Admission and Commitment to Body Dysmorphic Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in Women With Breast Cancer. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2019; 17 (4) :351-358

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-981-en.html

URL: http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-981-en.html

Esmaeil Sadri Damirch1

, Fariba Esmaeili Ghazivaoloii2

, Fariba Esmaeili Ghazivaoloii2

, Davod Fathi2

, Davod Fathi2

, Shafigh Mehraban3

, Shafigh Mehraban3

, Soliman Ahmadboukani *2

, Soliman Ahmadboukani *2

, Fariba Esmaeili Ghazivaoloii2

, Fariba Esmaeili Ghazivaoloii2

, Davod Fathi2

, Davod Fathi2

, Shafigh Mehraban3

, Shafigh Mehraban3

, Soliman Ahmadboukani *2

, Soliman Ahmadboukani *2

1- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Educational Sciences and Psychology, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil. Iran.

2- Department of Educational Sciences, Faculty of Educational Sciences and Psychology, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran.

3- Department of Counseling, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Educational Sciences, Faculty of Educational Sciences and Psychology, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran.

3- Department of Counseling, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 590 kb]

(2222 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (5688 Views)

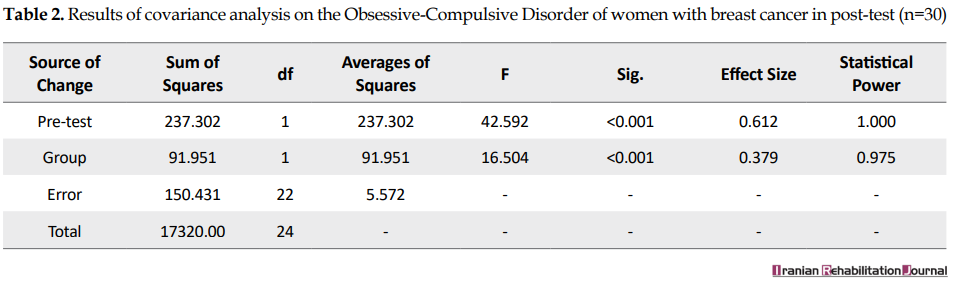

Based on the results of the covariance analysis test (Table 2), the F-value is 16.50 at a level of less than 0.001. In fact, the mean of the two groups was significantly different in the post-test. Therefore, there is a significant difference between the two treatment groups based on acceptance and commitment and control in the post-test of OCD.

Table 3 presents the results of covariance analysis for comparing two groups of acceptance and commitment-based therapy and control in obsessive-compulsive factors in the post-test. From the meaningful pillar, it is clear that both components of obsessive-compulsive and practical obsession in the post-test test were significantly different between the two groups at a level of less than 0.05.

Based on the results of the covariance analysis test (Table 4), the F-value is 11.56 at the level of less than 0.05. There is a significant difference between the two groups in the continuous follow-up.

Table 5 presents the results of covariance analysis for the comparison of the two groups in the obsessive components in the follow-up test.

Table 5 presents the results of covariance analysis for the comparison of two treatment groups based on acceptance and commitment and control in obsessive-compulsive factors in the follow-up test. From the meaningful pillar, it is clear that both components of obsessive-compulsive and practical obsession in the follow-up test were significantly different between the two groups at a level of less than 0.05. Therefore, there is a significant difference between the two groups of acceptance and commitment therapy and the control group in both components of OCD. That is, the group based on acceptance and commitment compared with the control group reported higher scores in both components of OCD.

4. Discussion

The results of this study showed that acceptance and commitment therapy reduced physical dissatisfaction and fear of evaluating the negation of the experimental group compared to the control group in the post-test stage. The results are in accordance with the findings of Rafiee et al., Habibollahi and Soltanizadeh [18, 20].

Acceptance and commitment therapy techniques emphasized cognitive blend reduction. When the cognitive blending decreases, the individual is distracted from the content of the thoughts. Cognitive fault training teaches clients only thoughts, emotions, memories, and physical memories. None of these internal events, when they are experienced, are inherently unsafe for human health. Their harmfulness comes from the fact that they experience harmful, unhealthy, and bad experiences that must be controlled and eliminated [22]. This method of treatment makes the clients feel unpleasant internal experiences without trying to control them and makes those experiences less likely to appear threatening. The reason for the success of treatment based on acceptance and commitment with various types of clinical disorders and different groups of people is that this approach focuses on functional processes instead of the form or frequencies of symptoms that are a disorder, which is subject to many disruptive behavioral manifestations they have. The results of this study can be compared with the results of a study by Herbert et al. [23]. In their research, it showed that the reduction of empirical avoidance, which is one of the components of acceptance and commitment, is linked to the reduction of social phobia symptoms, including the fear of negative evaluation.

Masuda et al. in a study showed that cognitive impairment techniques decrease self-evaluation thoughts as inferior thoughts [24]. When adherence and commitment to social phobia symptoms are used, in addition to processes of physical dissatisfaction, it seeks to change the response areas and actions instead of attempting to transform the content of mental events and focusing on the cycle of the disorder [11]. In spite of the individual experiences of fear signs, the judgment of the community, and emphasizing escaping or avoiding inappropriate internal experiences, it seems that it provides more of an empirical avoidance context and, therefore, exacerbates one’s problem. In the fear of negative evaluation, emotional control strategies people use (such as avoidance and relaxation) actually increase anxiety [25]. The therapist tries to get references to avoid admission. Hayes et al. argued that admission involving the experience of events is completely and unprotected as they are [12]; they also noted that clinicians, who are experientialists, may be overemphasized by the importance of changing all the unpleasant symptoms and do not pay attention to the importance of admission. In the absence of defending, the individual learns to look at the events of life as they are; they try not to interfere or change them because when they encounter irreplaceable events, they experience thoughts, emotions, and emotions that trigger confrontation strategies. With excitement or avoidance stress, but in admission, one learns to be aware of this issue in his/her life and does not attempt to eliminate it and this makes the intensity of avoidable coping strategies and his/her excitement decreases and the problem-oriented strategy increases understanding. Adoption-based treatment defines values as the chosen qualities of deliberately targeting their problems and tells clients to distinguish between choice and judicious judgments and choose values.

Working on values increases the motivation of the authorities to engage in treatment. Values are related to the above-mentioned processes. For example, they are important parts of admission and provide an incentive for admission. Acceptance can be a difficult and sometimes painful experience; the clarification F-values facilitates this suffering and it is a difficult problem [13]. Among the limitations of this study, there were some intensive therapeutic sessions and no access to the population studied. In the following research, it is suggested to compare the effectiveness of this treatment with drug therapy and combination therapies; the use of adherence and adherence-based therapy along with other treatments in various welfare centers, educational centers, and clinics can also be effective in reducing OCD or on other strata.

5. Conclusion

The coherence of the findings with the results of previous studies both inside and outside the country confirm the effectiveness of this therapeutic intervention on psychological disorders. Therefore, it seems that this method, because of its low cost and practicality, is an effective and economical way to treat OCD that can be used in different situations and for multiple clinical and chronic problems.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was approved by the Human Ethics Research Committee of the Mohaghegh Ardabil University of Iran.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Esmaeil Sadri Damirchi, Fariba Esmaeili Ghazivaoloii; Methodology: Shafigh Mehraban; Investigation: Davod Fathi; Writing-Review & editing: Soliman Ahmadboukani

Conflict of interest

The authors certify that they have no affiliation with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials dismissed in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all women, who came to Khansari and Shariati Hospitals, as well as the hospital officials.

References

Full-Text: (1298 Views)

1. Introduction

Among all types of cancer, breast cancer is the most common among women and is the second leading cause of death in women aged 35-55 years old [1]. Of 8 women between the ages of 45 and 55, 1 person has a chance to develop liver cancer. Breast cancer is a disease that causes severe psychic effects [1]. The physical condition and appearance of patients with cancer are affected by illness changes (such as hair loss, loss of a member like one person’s amputation, etc.). The same changes result in unpleasant thoughts and feelings about their bodies that eventually develop Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) in their bodies [2].

Body dysmorphic disorder, as a seriously debilitating disorder, is often difficult to treat and most women suffer from it [3]. This disorder is characterized by intensive mental conflict, a slight defect or hypothetical appearance on the person’s look [4]. People with body dysmorphic disorder have a physical image problem with how they see their physical appearance, not how they really are [5]. The research on the physical image of these patients has shown that the image in these people’s minds does not coincide with others’ images in their own minds. Feelings like hopelessness or embarrassment of processes such as rumination and automatic thinking are other characteristics of these people and it is believed that a negative evaluation of the body image causes feelings of shame, hatred, and depression [6]. On the other hand, people with breast cancer, body dysmorphic disorder, fear of negative assessment, physical dissatisfaction, and low self-esteem for engaging in daily activities and avoiding social activities can lead to serious social isolation [7].

Evidence suggests that body image plays a significant role in the psychological functioning of patients with hepatic cancer [8]. It showed that patients, who have better feelings about their bodies, have stronger beliefs in their abilities to cope with and treat the disease. In addition, research on factors affecting the body image of patients with breast cancer is inadequate [9].

A significant number of patients with OCD did not respond to conventional therapies and drug therapies, and some factors such as low motivation, negative expectations of treatment, disapproval, and disability in performing prescribed tasks reduced the effectiveness of these therapies [10].

Despite medical therapy for treating this disorder, several psychological treatments have been developed over the years. One of these therapies includes third wave therapy. Acceptance and commitment therapy is one of the third-generation behavioral treatments introduced by Hayes et al. since the 1980s. This approach is essentially a contextualization therapy that tries to change verbal social behavior instead of changing clinical content [11]. In this treatment, one tries to increase the psychological relationship of an individual with his thoughts and feelings. The main purpose of the treatment is to create psychological flexibility. Psychological flexibility on acceptance and commitment treatment is based on 6 main processes, including acceptance, cognitive, defection being present, self as context, illumination of-values, and committed actions. Each effect of these processes on human linguistic practice is interconnected and also affects one another to enhance flexibility [12]. In this perspective, the inability to experience in-person processes, such as exhilarating emotional states, leads to behaviors for emancipation or neglection [13]. Therefore, in the conceptualizing of the body dysmorphic disorder, the body can point to the role of these factors in a person. Treatment based on acceptance and commitment for people with body dysmorphic disorder shows that these people greatly value for individual attractiveness, which leads to the loss of other important values in their lives. Based on this treatment, individuals are asked to identify other important values of their lives and are committed to pursuing them [14].

Rafiee et al. showed that acceptance and commitment therapy is consistent with reducing symptoms of anxiety and satisfaction in the body image of the obsessed women [15]. Mohabbat Bahar et al. showed that group psychotherapy based on acceptance and commitment is an effective way to increase the quality of life of patients with breast cancer [16]. According to Branstette et al., the effect of acceptance and commitment therapy on the psychological symptoms of patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy proves that acceptance and commitment therapy in the 12th session led to anxiety, stress, and depression in patients with cancer [17]. Forman et al. have shown that adherence-based treatment and commitment to treating shame and embarrassment associated with the body is effective [18]. The post-test scores confirm the degree of depression, the effect of treatment, and commitment to decreasing the rate of depression in patients with diabetes. In research carried out by Pearson et al., adherence-based treatment reduces eating habits in women with physical-health concerns [19].

Generally, studies related to the effectiveness of curing based on acceptance and commitment to the deformity of women’s bodies are performed. So far, no research has been conducted with the aim of investigating the effectiveness of treatment based on acceptance and commitment to OCD in the body of women with breast cancer. Given that women with breast cancer are vulnerable to mental illnesses, especially those with a disordered body, successful treatment of this disorder in this population can play an important role in improving their mental health. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the efficacy of acceptance and commitment therapy for OCD in women with breast cancer.

2. Methods

The present study is a quasi-experimental research with a pre-test; post-test; follow-up design with the control group; the aim of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy-based treatment to OCD in women with breast cancer in 2016. The statistical population of this study included all women referred to Khansari and Shariati Hospitals in Arak in 2016.

Research tools

1. Demographic information questionnaire: The questionnaire included questions about the level of education of the subjects, their age, educational level, and their economic status.

2. Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale modified for Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD-YBOCS): The instrument has 12 questions that measure the symptoms of disorientation in the body and has a 2-fold 2-factor structure (OCD) with 2 additional questions about insight and avoidance. In general, studies show that this has a desirable validity and reliability [20]. Rabiee et al. investigated it in an Iranian sample and its psychometric properties and showed that the modified scale is practical for deforming the body of desired reliability and validity [21].

Data analysis

The statistical population of this study included all women referred to Khansari and Shariati Hospitals in Arak in 2016. Of these, 30 patients were selected by the purposive sampling method; they were randomly assigned to the control and experimental groups (15 patients in each group). The experimental group received 8 sessions (each session 60 minutes) undergoing acceptance and commitment books of Hayes et al. but the control group did not receive any intervention [11].

The inclusion criteria of the present study included obsessive-compulsive in relation to the body’s deformity, willingness to be present in the research, and the ability to attend the experimental group; the exclusion criterion of the study was lacking the inclusion criteria. They also assured the subjects that all information would be kept confidential and if they did not want to attend the sessions, they could refuse to attend the group therapy sessions. According to the present research, to analyze the data and to control the pre-sampling method, the covariance analysis method was used. The data were analyzed by SPSS V. 24.

3. Results

In the present study, 30 women with OCD were diagnosed with debilitating body defects. Descriptive statistics showed that the Mean±SD age of the control group was 32.166±7.33 and the Mean±SD age of the experimental group was 34.102±8.18.

Table 1 presents the Mean±SD of pre-test and post-test scores of obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. results showed that the Mean±SD of pre-test in control group was 22.90±2.07 and the Mean±SD of post-test in control group was 23±2. the Mean±SD of pre-test in experiment group was 27.30±4.34 and the Mean±SD of post-test in experiment group was 23±1.15.

Among all types of cancer, breast cancer is the most common among women and is the second leading cause of death in women aged 35-55 years old [1]. Of 8 women between the ages of 45 and 55, 1 person has a chance to develop liver cancer. Breast cancer is a disease that causes severe psychic effects [1]. The physical condition and appearance of patients with cancer are affected by illness changes (such as hair loss, loss of a member like one person’s amputation, etc.). The same changes result in unpleasant thoughts and feelings about their bodies that eventually develop Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) in their bodies [2].

Body dysmorphic disorder, as a seriously debilitating disorder, is often difficult to treat and most women suffer from it [3]. This disorder is characterized by intensive mental conflict, a slight defect or hypothetical appearance on the person’s look [4]. People with body dysmorphic disorder have a physical image problem with how they see their physical appearance, not how they really are [5]. The research on the physical image of these patients has shown that the image in these people’s minds does not coincide with others’ images in their own minds. Feelings like hopelessness or embarrassment of processes such as rumination and automatic thinking are other characteristics of these people and it is believed that a negative evaluation of the body image causes feelings of shame, hatred, and depression [6]. On the other hand, people with breast cancer, body dysmorphic disorder, fear of negative assessment, physical dissatisfaction, and low self-esteem for engaging in daily activities and avoiding social activities can lead to serious social isolation [7].

Evidence suggests that body image plays a significant role in the psychological functioning of patients with hepatic cancer [8]. It showed that patients, who have better feelings about their bodies, have stronger beliefs in their abilities to cope with and treat the disease. In addition, research on factors affecting the body image of patients with breast cancer is inadequate [9].

A significant number of patients with OCD did not respond to conventional therapies and drug therapies, and some factors such as low motivation, negative expectations of treatment, disapproval, and disability in performing prescribed tasks reduced the effectiveness of these therapies [10].

Despite medical therapy for treating this disorder, several psychological treatments have been developed over the years. One of these therapies includes third wave therapy. Acceptance and commitment therapy is one of the third-generation behavioral treatments introduced by Hayes et al. since the 1980s. This approach is essentially a contextualization therapy that tries to change verbal social behavior instead of changing clinical content [11]. In this treatment, one tries to increase the psychological relationship of an individual with his thoughts and feelings. The main purpose of the treatment is to create psychological flexibility. Psychological flexibility on acceptance and commitment treatment is based on 6 main processes, including acceptance, cognitive, defection being present, self as context, illumination of-values, and committed actions. Each effect of these processes on human linguistic practice is interconnected and also affects one another to enhance flexibility [12]. In this perspective, the inability to experience in-person processes, such as exhilarating emotional states, leads to behaviors for emancipation or neglection [13]. Therefore, in the conceptualizing of the body dysmorphic disorder, the body can point to the role of these factors in a person. Treatment based on acceptance and commitment for people with body dysmorphic disorder shows that these people greatly value for individual attractiveness, which leads to the loss of other important values in their lives. Based on this treatment, individuals are asked to identify other important values of their lives and are committed to pursuing them [14].

Rafiee et al. showed that acceptance and commitment therapy is consistent with reducing symptoms of anxiety and satisfaction in the body image of the obsessed women [15]. Mohabbat Bahar et al. showed that group psychotherapy based on acceptance and commitment is an effective way to increase the quality of life of patients with breast cancer [16]. According to Branstette et al., the effect of acceptance and commitment therapy on the psychological symptoms of patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy proves that acceptance and commitment therapy in the 12th session led to anxiety, stress, and depression in patients with cancer [17]. Forman et al. have shown that adherence-based treatment and commitment to treating shame and embarrassment associated with the body is effective [18]. The post-test scores confirm the degree of depression, the effect of treatment, and commitment to decreasing the rate of depression in patients with diabetes. In research carried out by Pearson et al., adherence-based treatment reduces eating habits in women with physical-health concerns [19].

Generally, studies related to the effectiveness of curing based on acceptance and commitment to the deformity of women’s bodies are performed. So far, no research has been conducted with the aim of investigating the effectiveness of treatment based on acceptance and commitment to OCD in the body of women with breast cancer. Given that women with breast cancer are vulnerable to mental illnesses, especially those with a disordered body, successful treatment of this disorder in this population can play an important role in improving their mental health. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the efficacy of acceptance and commitment therapy for OCD in women with breast cancer.

2. Methods

The present study is a quasi-experimental research with a pre-test; post-test; follow-up design with the control group; the aim of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy-based treatment to OCD in women with breast cancer in 2016. The statistical population of this study included all women referred to Khansari and Shariati Hospitals in Arak in 2016.

Research tools

1. Demographic information questionnaire: The questionnaire included questions about the level of education of the subjects, their age, educational level, and their economic status.

2. Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale modified for Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD-YBOCS): The instrument has 12 questions that measure the symptoms of disorientation in the body and has a 2-fold 2-factor structure (OCD) with 2 additional questions about insight and avoidance. In general, studies show that this has a desirable validity and reliability [20]. Rabiee et al. investigated it in an Iranian sample and its psychometric properties and showed that the modified scale is practical for deforming the body of desired reliability and validity [21].

Data analysis

The statistical population of this study included all women referred to Khansari and Shariati Hospitals in Arak in 2016. Of these, 30 patients were selected by the purposive sampling method; they were randomly assigned to the control and experimental groups (15 patients in each group). The experimental group received 8 sessions (each session 60 minutes) undergoing acceptance and commitment books of Hayes et al. but the control group did not receive any intervention [11].

The inclusion criteria of the present study included obsessive-compulsive in relation to the body’s deformity, willingness to be present in the research, and the ability to attend the experimental group; the exclusion criterion of the study was lacking the inclusion criteria. They also assured the subjects that all information would be kept confidential and if they did not want to attend the sessions, they could refuse to attend the group therapy sessions. According to the present research, to analyze the data and to control the pre-sampling method, the covariance analysis method was used. The data were analyzed by SPSS V. 24.

3. Results

In the present study, 30 women with OCD were diagnosed with debilitating body defects. Descriptive statistics showed that the Mean±SD age of the control group was 32.166±7.33 and the Mean±SD age of the experimental group was 34.102±8.18.

Table 1 presents the Mean±SD of pre-test and post-test scores of obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. results showed that the Mean±SD of pre-test in control group was 22.90±2.07 and the Mean±SD of post-test in control group was 23±2. the Mean±SD of pre-test in experiment group was 27.30±4.34 and the Mean±SD of post-test in experiment group was 23±1.15.

Based on the results of the covariance analysis test (Table 2), the F-value is 16.50 at a level of less than 0.001. In fact, the mean of the two groups was significantly different in the post-test. Therefore, there is a significant difference between the two treatment groups based on acceptance and commitment and control in the post-test of OCD.

Table 3 presents the results of covariance analysis for comparing two groups of acceptance and commitment-based therapy and control in obsessive-compulsive factors in the post-test. From the meaningful pillar, it is clear that both components of obsessive-compulsive and practical obsession in the post-test test were significantly different between the two groups at a level of less than 0.05.

Based on the results of the covariance analysis test (Table 4), the F-value is 11.56 at the level of less than 0.05. There is a significant difference between the two groups in the continuous follow-up.

Table 5 presents the results of covariance analysis for the comparison of the two groups in the obsessive components in the follow-up test.

Table 5 presents the results of covariance analysis for the comparison of two treatment groups based on acceptance and commitment and control in obsessive-compulsive factors in the follow-up test. From the meaningful pillar, it is clear that both components of obsessive-compulsive and practical obsession in the follow-up test were significantly different between the two groups at a level of less than 0.05. Therefore, there is a significant difference between the two groups of acceptance and commitment therapy and the control group in both components of OCD. That is, the group based on acceptance and commitment compared with the control group reported higher scores in both components of OCD.

4. Discussion

The results of this study showed that acceptance and commitment therapy reduced physical dissatisfaction and fear of evaluating the negation of the experimental group compared to the control group in the post-test stage. The results are in accordance with the findings of Rafiee et al., Habibollahi and Soltanizadeh [18, 20].

Acceptance and commitment therapy techniques emphasized cognitive blend reduction. When the cognitive blending decreases, the individual is distracted from the content of the thoughts. Cognitive fault training teaches clients only thoughts, emotions, memories, and physical memories. None of these internal events, when they are experienced, are inherently unsafe for human health. Their harmfulness comes from the fact that they experience harmful, unhealthy, and bad experiences that must be controlled and eliminated [22]. This method of treatment makes the clients feel unpleasant internal experiences without trying to control them and makes those experiences less likely to appear threatening. The reason for the success of treatment based on acceptance and commitment with various types of clinical disorders and different groups of people is that this approach focuses on functional processes instead of the form or frequencies of symptoms that are a disorder, which is subject to many disruptive behavioral manifestations they have. The results of this study can be compared with the results of a study by Herbert et al. [23]. In their research, it showed that the reduction of empirical avoidance, which is one of the components of acceptance and commitment, is linked to the reduction of social phobia symptoms, including the fear of negative evaluation.

Masuda et al. in a study showed that cognitive impairment techniques decrease self-evaluation thoughts as inferior thoughts [24]. When adherence and commitment to social phobia symptoms are used, in addition to processes of physical dissatisfaction, it seeks to change the response areas and actions instead of attempting to transform the content of mental events and focusing on the cycle of the disorder [11]. In spite of the individual experiences of fear signs, the judgment of the community, and emphasizing escaping or avoiding inappropriate internal experiences, it seems that it provides more of an empirical avoidance context and, therefore, exacerbates one’s problem. In the fear of negative evaluation, emotional control strategies people use (such as avoidance and relaxation) actually increase anxiety [25]. The therapist tries to get references to avoid admission. Hayes et al. argued that admission involving the experience of events is completely and unprotected as they are [12]; they also noted that clinicians, who are experientialists, may be overemphasized by the importance of changing all the unpleasant symptoms and do not pay attention to the importance of admission. In the absence of defending, the individual learns to look at the events of life as they are; they try not to interfere or change them because when they encounter irreplaceable events, they experience thoughts, emotions, and emotions that trigger confrontation strategies. With excitement or avoidance stress, but in admission, one learns to be aware of this issue in his/her life and does not attempt to eliminate it and this makes the intensity of avoidable coping strategies and his/her excitement decreases and the problem-oriented strategy increases understanding. Adoption-based treatment defines values as the chosen qualities of deliberately targeting their problems and tells clients to distinguish between choice and judicious judgments and choose values.

Working on values increases the motivation of the authorities to engage in treatment. Values are related to the above-mentioned processes. For example, they are important parts of admission and provide an incentive for admission. Acceptance can be a difficult and sometimes painful experience; the clarification F-values facilitates this suffering and it is a difficult problem [13]. Among the limitations of this study, there were some intensive therapeutic sessions and no access to the population studied. In the following research, it is suggested to compare the effectiveness of this treatment with drug therapy and combination therapies; the use of adherence and adherence-based therapy along with other treatments in various welfare centers, educational centers, and clinics can also be effective in reducing OCD or on other strata.

5. Conclusion

The coherence of the findings with the results of previous studies both inside and outside the country confirm the effectiveness of this therapeutic intervention on psychological disorders. Therefore, it seems that this method, because of its low cost and practicality, is an effective and economical way to treat OCD that can be used in different situations and for multiple clinical and chronic problems.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was approved by the Human Ethics Research Committee of the Mohaghegh Ardabil University of Iran.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Esmaeil Sadri Damirchi, Fariba Esmaeili Ghazivaoloii; Methodology: Shafigh Mehraban; Investigation: Davod Fathi; Writing-Review & editing: Soliman Ahmadboukani

Conflict of interest

The authors certify that they have no affiliation with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials dismissed in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all women, who came to Khansari and Shariati Hospitals, as well as the hospital officials.

References

- Mokhtary L, Habibpour Z, Khorami Marekani A. Assessing health beliefs and breast cancer early detection behaviors among female healthcare providers in Tabriz health centers. The Journal of Urmia Nursing and Midwifery Faculty. 2013; 11(4):299-308.

- Moreira H, Silva S, Marques A, Canavarro MC. The Portuguese version of the Body Image Scale (BIS)-psychometric properties in a sample of breast cancer patients. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2010; 14(2):111-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.ejon.2009.09.007] [PMID]

- Neziroglu F, Khemlani-Patel S. Therapeutic approaches to body dysmorphic disorder. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention. 2003; 3(3):307-22. [DOI:10.1093/brief-treatment/mhg023]

- Buhlmann U, Glaesmer H, Mewes R, Fama JM, Wilhelm S, Brähler E, et al. Updates on the prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder: A population-based survey. Psychiatry Research. 2010; 178(1):171-5. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2009.05.002] [PMID]

- Bordner MA. A cognitive-behavioral treatment program for body dysmorphic disorder. Michigan: ProQuest; 2007.

- Kollei I, Brunhoeber S, Rauh E, De Zwaan M, Martin A. Body image, emotions and thought control strategies in body dysmorphic disorder compared to eating disorders and healthy controls. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2012; 72(4):321-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.12.002] [PMID]

- Fang A, Hofmann SG. Relationship between social anxiety disorder and body dysmorphic disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010; 30(8):1040-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.08.001] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Pikler V, Winterowd C. Racial and body image differences in coping for women diagnosed with breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2003; 22(6):632-7. [DOI:10.1037/0278-6133.22.6.632] [PMID]

- Moreira H, Canavarro MC. A longitudinal study about the body image and psychosocial adjustment of breast cancer patients during the course of the disease. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2010; 14(4):263-70. [DOI:10.1016/j.ejon.2010.04.001] [PMID]

- Amani M, Abolghasemi A, Ahadi B, Narimani M. The prevalence of obsessive-compulsive disorder among the women 20 to 40 years old of Ardabil city, western part of Iran. Journal of Fundamentals of Mental Health. 2013; 15(59):233-42.

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy. New York: Guilford Press; 1999.

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD. A practical guide to acceptance and commitment therapy. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media; 2004. [DOI:10.1007/978-0-387-23369-7]

- Blackledge JT, Hayes SC. Emotion regulation in acceptance and commitment therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2001; 57(2):243-55. [DOI:10.1002/1097-4679(200102)57:23.0.CO;2-X]

- Habibollahi A, Soltanizadeh M. [Efficacy of acceptance and commitment therapy on body dissatisfaction and fear of negative evaluation in girl adolescents with body dysmorphic disorder. Journal of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences (Persain)]. 2016; 25(134):278-90.

- Rafiee M, Sedrpoushan N, Abedi MR. Study and investigate the effect of acceptance and commitment therapy on reducing anxiety symptoms and body image dissatisfaction in obese. Journal of Social Welfare and Human Rights. 2013; 1(2):477-85.

- Khanizadeh Balderlou K, Alizadeh M, Koorana AE. [The effectiveness of group psychotherapy based on acceptance and commitment on quality of life in women with breast cancer(Persain)]. The Journal of Urmia University of Medical Sciences. 2016; 27(5):365-74.

- Branstetter A, Wilson K, Hildebrandt M, Mutch D. Improving psychological adjustment among cancer patients: ACT and CBT. Association for Advancement of Behavior Therapy, New Orleans. 2004; 35:732.

- Forman EM, Butryn ML, Hoffman KL, Herbert JD. An open trial of an acceptance-based behavioral intervention for weight loss. Cognitive and Behavioral practice. 2009; 16(2):223-35. [DOI:10.1016/j.cbpra.2008.09.005]

- Pearson AN, Follette VM, Hayes SC. A pilot study of acceptance and commitment therapy as a workshop intervention for body dissatisfaction and disordered eating attitudes. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2012; 19(1):181-97. [DOI:10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.03.001]

- Phillips KA, Hollander E, Rasmussen SA, Aronowitz BR. A severity rating scale for body dysmorphic disorder: Development, reliability, and validity of a modified version of the Yale-Brown obsessive compulsive scale. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1997; 33(1):17.

- Rabiee M, Khorramdel K, Kalantari M, Molavi H. [Factor structure, validity and reliability of the modified Yale-Brown obsessive compulsive scale for body dysmorphic disorder in students (Persain)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2010; 15(4):343-50.

- Hayes SC. Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behavior Therapy. 2004; 35(4):639-65. [DOI:10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80013-3]

- Dalrymple KL, Herbert JD. Acceptance and commitment therapy for generalized social anxiety disorder: A pilot study. Behavior Modification. 2007; 31(5):543-68. [DOI:10.1177/0145445507302037] [PMID]

- Masuda A, Hayes SC, Sackett CF, Twohig MP. Cognitive defusion and self-relevant negative thoughts: Examining the impact of a ninety year old technique. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004; 42(4):477-85. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2003.10.008] [PMID]

- Luoma JB, Kohlenberg BS, Hayes SC, Fletcher L. Slow and steady wins the race: A randomized clinical trial of acceptance and commitment therapy targeting shame in substance use disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012; 80(1):43-53. [DOI:10.1037/a0026070] [PMID] [PMCID]

Article type: Original Research Articles |

Subject:

Counseling

Received: 2019/01/1 | Accepted: 2019/04/9 | Published: 2019/12/29

Received: 2019/01/1 | Accepted: 2019/04/9 | Published: 2019/12/29

Send email to the article author